THE ART, LITERATURE, ADVENTURE, LORE & LEARNING OF THE SEA

$4.95 SPRING 2023 No. 182 NATIONAL MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

14k 18k

A - Fish Float Sphere with Aqua Chalcedony Pendant (U.S. Patent D678,110)-----------n/a -------------$2100.

B - Flemish Coil Pendant (matching earrings available) ----------------------------------------------$1650. ------------$2100.

C - Compass Rose with working compass Pendant -----------------------------------------------$2100. ------------$2900.

D - Correa/Chart Metalworks 3/4" Sailboat Pendant (additional designs available) -- $1850. ------------$2500.

E - Bowline Knot Earrings (please specify dangle or stud) ------------------------------------------$1100. ------------$1500.

F - Deck Prism Anchor Chain Dangle Earrings (matching pendant available) --------------n/a -------------$2300.

G - Monkey's Fist Stud Earrings (matching pendants available)---------------------------------$1400. ------------$1900.

H - Original Working Shackle Earrings ------------------------------------------------------------------------$950. ------------$1300.

I - Two Strand Turk's Head Ring with sleeve (additional designs available) -------------$2300. ------------$2900.

J - Two Strand Turk's Head Bracelet --------------------------------------------------------------------------$4400. ------------$5900.

K - Port & Starboard Hand Enameled Dangle Earrings ------------------------------------------------n/a -------------$2250.

•18"

C A G B D J E H F K ® A.G.A. CORREA

SON JEWELRY DESIGN I PO Box 1 • 11 River Wind Lane, Edgecomb, Maine 04556 USA • M-F 10-5 ET customer.service@agacorrea.com • Please request our 52 page book of designs • 800.341.0788 • agacorrea.com Over 1000 more nautical jewelry designs at agacorrea.com ©All designs copyright A.G.A. Correa & Son 1969-2023 and handmade in the USA Jewelry shown actual size | Free shipping and insurance ©All designs copyright A.G.A. Correa & Son 1969-2023 and handmade in the USA

Rope Pendant Chain-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------$750.

&

On The Trail Of

COLUMBIA AND SNAKE RIVERS

Follow Lewis and Clark’s epic 19th-century expedition along the Columbia and Snake Rivers aboard the newest riverboats in the region. Enjoy unique shore excursions, scenic landscapes, and talented onboard experts who bring the region to life.

Cruise Close To Home ®

Columbia River Snake River Pacific Ocean Kalama Hells Canyon Columbia River Gorge Astoria Multnomah Falls The Dalles Umatilla Richland Spokane Clarkston Lewiston Portland Hayden Island Stevenson Hood River OREGON OREGON WASHINGTON Mt. Hood Pendleton Mount St. Helens Experience the Grandeur of Multnomah Falls AmericanCruiseLines.com Call 866-229-3807 to request a FREE Cruise Guide

LEWIS & CLARK

Explore the decks of the last Destroyer Escort afloat in America.

518-431-1943 ussslater.org

A TROPHY OF WAR DISCOVERED!

Climb the tower at the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum for panoramic views and explore history through underwater archaeology, a shipwreck exhibit, conservation lab, traditional boatbuilding, children’s activities, and more!

Discover the maritime heritage of St. Augustine, including our latest discovery – a pewter button from a 1782 British shipwreck with the letters “U.S.A.” distinctly revealed on its front side. Learn how it may have been a trophy of war.

15% Save Online Use code: SH15

Or present this code for 10% off on general admission

staugustinelighthouse.org

St.

904-829-0745

100 Red Cox Drive,

Augustine, FL 32080

J.P.URANKERWOODCARVER WWW.JPUWOODCARVER.COM THETRADITION OFHANDCARVED EAGLES CONTINUES TODAY (508) 939-1447 ★ ★ ★ ★

•

CONTENTS

10 National Maritime Awards Dinner and NMHS Invitational Art Gallery

In May, NMHS will celebrate three driving forces of the maritime community and their outstanding contributions at the 12th National Maritime Awards Dinner in Washington, DC. A showcase of contemporary marine art will be for sale, with proceeds bene ting NMHS.

16 Historic Ships on a Lee Shore: Schooners on the Move by Deirdre O’Regan

After many years in various stages of rebuild, the 1885 Coronet and 1894 Ernestina-Morrissey are back in the water, while in December the 1921 shing schooner L. A. Dunton was hauled out for a multi-year restoration at Mystic Seaport Museum.

22 All Hands on Deck: Storms, Turmoil, and a Rompin’ Good Sail Aboard the Tall Ship Rose by Will Sofrin

You might think that sailing a square-rigged ship from the North Atlantic to California in the dead of winter would be asking for trouble. And you’d be right. In an excerpt from his new book, Will Sofrin takes us onboard the tall ship Rose in what proved to be an epic voyage.

28 Curator’s Corner—Historic Photos from the Archives by Je rey Smith

Columbia River Maritime Museum curator Je rey Smith shares a photo from 1938 showing a motor yacht about to be launched in Astoria, Oregon. is same vessel was recently donated to the museum; she arrived under her own power for a grand homecoming last August.

30 S.E.A. and the History of Ocean Plastic Research by Chloe Beittel, Ava De Leon, and Isabelle Stewart

Sea Education Association has been studying the prevalence of microplastics in the oceans for 50 years. Recent interns share how a research project in the Sargasso Sea inadvertently started it all, and how S.E.A.’s curriculum has evolved to help confront today’s environmental crises.

36 A Ship, Youth, and the Sea— Black Pearl’s Role in American Sail Training

by Nicolas Hardisty

by Nicolas Hardisty

Tall Ships America’s historian Nic Hardisty traces the colorful history of the little brigantine that played a pivotal role in the founding of the sail training movement in the United States.

46 Beyond the Light: Identity and Place in 19th-Century Danish Art by Freyda Spira, Stephanie Schrader, and omas Lederballe

A new exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art takes an intimate look at the masters of the Danish Golden Age and how they interpreted the turbulent time after the Napoleonic Wars when Denmark was adapting to its changing cultural identity, much of it tied to the sea.

Cover: View from the Citadel Ramparts in Copenhagen by Moonlight , 1839, by Martinus Rørbye. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (See pp. 46–48.)

Sea History and the National Maritime Historical Society

Sea History e-mail: seahistory@gmail.com

Website: www.seahistory.org

• NMHS e-mail: nmhs@seahistory.org

• Ph: 914 737-7878; 800 221-NMHS

MEMBERSHIP is invited. Afterguard $10,000; Benefactor $5,000; Plankowner $2,500; Sponsor $1,000; Donor $500; Patron $250; Friend $100; Regular $45. All members outside the USA please add $20 for postage. Sea History is sent to all members. Individual copies cost $4.95.

SEA HISTORY (issn 0146-9312) is published quarterly by the National Maritime Historical Society, 1000 North Division St., #4, Peekskill NY 10566 USA. Periodicals postage paid at Peekskill NY 10566 and add’l mailing o ces.

COPYRIGHT © 2023 by the National Maritime Historical Society. Tel: 914 737-7878.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Sea History, 1000 North Division St., #4, Peekskill NY 10566.

DEPARTMENTS SEA

No. 182 SPRING 2023 4 Deck L og & L etters 8 NMHS: A C ause in Motion 40 Sea History for K ids 50 Ship Notes, Seaport & Museum News 58 R eviews 64 Patrons NATIONAL MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

HISTORY

30 sea education association

36

22

16

tall ships america

photo by scott hamann

mystic seaport museum

DECK LOG

Looking at Maritime History in Our 60th Year and Beyond

It’s 2023, the National Maritime Historical Society’s 60th year, and what an interesting time we live in for maritime history—a eld that is continuously progressing, advancing technologically, becoming more inclusive, and focusing globally in an e ort to protect the oceans and waterways that connect us all.

From sailing ships and lighthouses to shipwrecks and naval heroes, there’s something about the history of the sea that continues to draw us in. Beyond the stories of ships and sailors, our maritime heritage encompasses commerce, naval warfare, shipbuilding, and environmental science. Studying the history of seafaring can lead to a better understanding of geography and economics, and learning about shipbuilding facilitates scholarship in engineering, physics, and technology. Studying maritime history provides insight into the development of societies and the interactions of people and cultures across the oceans, the impact of globalization, and the role of the sea in shaping how we live today.

Advancing technologies help us discover (or rediscover) our history in ways our predecessors couldn’t have imagined and enables us to better preserve our historic sites and artifacts, big and small. From the early compass to the sextant, the transition from sail to steam to diesel, from wood to iron and steel, and modern developments in radar, global positioning systems, and the autonomous ships of the future, maritime pursuits have always been shaped by technology. Today we use 3D scanning and printing to create accurate replicas of historic ships, while virtual and augmented reality technology helps bring history to life in new and interactive ways. DNA analysis is helping us identify and study shipwreck cargoes and sites. Digital archives and databases allow us to preserve and share historical documents and artifacts, and the use of online platforms connects maritime heritage professionals with new audiences.

Historians have tremendous power to shape historical narratives, and with this power comes the responsibility to expand our understanding of maritime history with narratives that re ect all human experience. A growing focus on diversity and inclusivity in the maritime history eld creates space to share the underreported stories and contributions of women, Indigenous communities, people of color, and others, and helps us make connections between historical events and current-day contexts. Now more than ever, museums, historical societies, and publications like Sea History are working to expand their stories, collections, and programs to re ect the diversity of human experience—giving us all a richer understanding of our past and present.

Advances in marine and environmental science remind us that we are a blue planet and that maritime heritage organizations should play an important role in efforts to protect and preserve our marine ecosystems. e history of our oceans may be the most important maritime history subject of all time, encompassing not just humankind’s impact on climate change, rising seawater temperatures, ocean acidi cation, damage to marine habitats, pollution from plastics and other waste, over shing, and rising sea levels that threaten waterfront communities and maritime museums— but also e orts to counteract these impacts and protect our oceans and waterways.

In the inspiring words of Native Hawaiian navigator Nainoa ompson, “We can’t care for something we don’t understand. is is the purpose of why we explore and why we voyage.” From our coverage of marine protection e orts in Sea History to National Marine Sanctuaries presentations at our Annual Meeting in April (see page 8), to our inaugural Marine Conservation Award at the National Maritime Awards Dinner in May (see pp. 10–13), we hope you will support us as we renew and reinvigorate our vision for our 60th year and beyond. How do you think we can better support the maritime heritage eld and have a positive impact on the maritime world around us? How can we help realize the impact you want to see? We look forward to learning more about your vision as we shape ours.

—Jessica MacFarlane, NMHS Executive Director

NATIONAL MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

LEADERSHIP CIRCLE: Peter Aron, Guy

E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald, William

H. White

OFFICERS & TRUSTEES: Chairman, James

A. Noone; Vice Chairman, Richardo R. Lopes; Vice Presidents: Jessica MacFarlane; Deirdre

E. O’Regan, Wendy Paggiotta; Treasurer, William H. White; Secretary, Capt. Je rey McAllister; Trustees: Charles B. Anderson; Walter R. Brown; CAPT Patrick Burns, USN (Ret.); CAPT Sally McElwreath Callo, USN (Ret.); William S. Dudley; David Fowler; Karen Helmerson; VADM Al Konetzni, USN (Ret.); K. Denise Rucker Krepp; Guy E. C. Maitland; Salvatore Mercogliano; Michael Morrow; Richard Patrick O’Leary; Ronald L. Oswald; Timothy J. Runyan; Richard Scarano; Capt. Cesare Sorio; Jean Wort

CHAIRMEN EMERITI: Walter R. Brown, Alan G. Choate, Guy E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald; Howard Slotnick (1930–2020)

FOUNDER: Karl Kortum (1917–1996)

PRESIDENTS EMERITI: Burchenal Green, Peter Stanford (1927–2016)

OVERSEERS: Chairman, RADM David C. Brown, USMS (Ret.); RADM Joseph F. Callo, USN (Ret.); Christopher J. Culver; Richard du Moulin; Alan D. Hutchison; Gary Jobson; Sir Robin Knox-Johnston; John Lehman; Capt. James J. McNamara; Philip J. Shapiro; H. C. Bowen Smith; John Stobart; Philip J. Webster; Roberta Weisbrod

NMHS ADVISORS: John Ewald, Steven A. Hyman, J. Russell Jinishian, Gunnar Lundeberg, Conrad Milster, William G. Muller, Nancy H. Richardson

SEA HISTORY EDITORIAL ADVISORY

BOARD: Chairman, Timothy Runyan; Norman Brouwer, Robert Browning, William Dudley, Lisa Egeli, Daniel Finamore, Kevin Foster, Cathy Green, John O. Jensen, Frederick Leiner, Joseph Meany, Salvatore Mercogliano, Carla Rahn Phillips, Walter Rybka, Quentin Snediker, William H. White

NMHS STAFF: Executive Director, Jessica MacFarlane; Vice President of Operations, Wendy Paggiotta; Director of Special Projects, Nicholas Raposo; Senior Sta Writer, Shelley Reid; Business Manager, Andrea Ryan; Manager of Educational Programs, Heather Purvis; Membership Coordinator, Marianne Pagliaro

SEA HISTORY: Editor, Deirdre E. O’Regan; Advertising Director, Wendy Paggiotta

Sea History is printed by e Lane Press, South Burlington, Vermont, USA.

4 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

Louise Arner Boyd’s Arctic Sea Voyages ank you for running Joanna Kafarowski’s article on Louise Arner Boyd and her East Greenland expeditions on board the Norwegian sealer Veslekari. Ms. Boyd is a well-known local hero here in San Rafael, California, and her successes in leading Arctic expeditions in the 1930s are well deserving of this wider recognition. Such success was largely due to her egalitarian manner of interacting with the Norwegian captain and crew on board, which was in many ways reciprocated.

Her next expedition was not to be so harmonious. By late 1940, it had become clear that the United States would not avoid becoming embroiled in World War II, which was already raging in Europe. e US government privately contacted Ms. Boyd to conduct a survey expedition northwards through Ba n Bay, for which she chartered Captain Bob Bartlett’s E e M. Morrissey (now schooner Ernestina-Morrissey). Boyd and Bartlett both kept daily logs of their own experiences during this expedition, each account rife with derisive comments about the skills and personal attributes of the other. ere was constant con ict as to who was “leader” of the expedition—the captain, or the charterer who had already led four Arctic expeditions of her own.

In 2021, I edited and published these journals covering August and September 1941 in a side-by-side, day-by-day format in e Socialite and the Sea Captain: Louise Arner Boyd and Captain Bob Bartlett at Sea, 1941 from Terra Nova Press. e informal handwritten journal entries also reveal much about the writers themselves—surprising hints of poetry and tenderness amid the rough-and-tumble world of polar exploration.

David H irzel San Rafael, California

Wisconsin’s Photographer Captain

Your “Curator’s Corner” photo selection in the recent issue of Sea History (181) was shot in 1890 by Captain Edward Carus, a wellknown master mariner and avid photographer from Manitowoc, Wisconsin, whose photographs document more than 50 years of Great Lakes maritime activity. Your readers may be interested to learn that the museum recently received a $25,000 grant

from West Foundation Directors’ Circle to begin work on the Maritime Heritage Plaza and Park. is project will create a new public park and educational space in downtown Manitowoc on the campus of the museum’s o -site storage facility, which, coincidentally, is also the site of Captain and Mrs. Carus’s former residence. Plans for the park include a public archaeological excavation of the Carus family home

site, as well as a large mural on the storage facility featuring his photographs.

One can imagine Captain Carus would be pleased that the view from his former front porch will now be punctuated with maritime artifacts recovered from local historic sites, including a massive anchor, a ship’s wheel, and the sail of a Manitowoc-built submarine. Meanwhile, a collection of more than 3,000 of his photographs can be viewed on the museum’s website (www.wisconsinmaritime.org).

C athy Green, E xecutive Director Wisconsin Maritime Museum

Erratum: First Vessels of the Continental Army (not Navy)

In the previous issue’s article examining the beginnings of marine insurance in the United States, the caption that accompanies a reproduction of the painting of the Continental Schooner Hannah by John F.

Join Us for a Voyage into History

Our seafaring heritage comes alive in the pages of Sea History, from the ancient mariners of Greece to Portuguese navigators opening up the ocean world to the heroic efforts of sailors in modern-day conficts. Each issue brings new insights and discoveries. If you love the sea, rivers, lakes, and

bays—if you appreciate the legacy of those who sail in deep water and their workaday craft, then you belong with us.

Join Today !

Mail in the form below, phone 1 800 221-NMHS (6647), or visit us at: www.seahistory.org

(e-mail: nmhs@seahistory.org)

Yes, I want to join the Society and receive Sea History quarterly. My contribution is enclosed. ($22.50 is for Sea History; any amount above that is tax deductible.) Sign me up as:

$45 Regular Member $100 Friend

$250 Patron $500 Donor Mr./Ms.

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 5

_________________________________________________________ZIP_______________ Return to: National Maritime Historical Society, 1000 North Division St., #4, Peekskill, NY 10566 182

____________________________________________________________________

Welcome Your Feedback! Please email correspondence to seahistory@gmail.com.

We

LETTERS

wisconsin maritime museum

Captain Edward Carus standing inside a ventilator on deck of the car ferry Pere Marquette 19, circa 1903–04.

us navy , nhhc

Schooner Hannah

Leavitt misidenti es the vessel as “for the use of the Continental Navy during the American Revolutionary War.” e 78-ton schooner Hannah was commissioned 24 August 1775 under the authority of the Continental Army. Hannah was never connected in any way to the Continental Navy, which was formed much later. For further discussion, see Sea History 179, Summer 2022, page 6. Also, e Army’s Navy Series, Volume I, Marine Transportation in War, e US Army Experience, 1775–1860 by Charles Dana Gibson with E. Kay Gibson.

E. K ay Gibson Hutchinson Island, Florida

1/8 page AD

THE FLEET IS IN.

Sit in the wardroom of a mighty battleship, touch a powerful torpedo on a submarine, or walk the deck of an aircraft carrier and stand where naval aviators have flown off into history. It’s all waiting for you when you visit one of the 175 ships of the Historic Naval Ships Association fleet.

www.HNSA.org

For information on all our ships and museums, see the HNSA website or visit us on Facebook.

6 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

THE HISTORIC NAVAL SHIPS ASSOCIATION

2.25x4.5_HNSA_FleetCOL#1085.pdf 6/5/12 10:47:40 CHESAPEAKE BAY MARITIME MUSEUM Your Chesapeake adventure begins here! 213 N. Talbot St., St. Michaels, MD | 410-745-2916 | cbmm.org

FIDDL ER’S GREEN

William N. Still Jr. (1932–2023)

Dr. William N. Still Jr. died on 8 January following a brief illness, and his loss is keenly felt, not only by friends and family but by the hundreds of colleagues and former students (many of whom became colleagues) he mentored. Bill was a giant in the maritime history world, a proli c author, enthusiastic educator, dedicated mentor, loving family man, and a generous soul with a wry sense of humor. Between his books and scholarship and the students he taught, encouraged, and guided, his legacy is secure and wide-reaching.

Bill Still was born and raised in Mississippi. He earned his bachelor’s degree at Mississippi College, completed his doctorate at the University of Alabama, and spent two years serving in the US Navy aboard the carrier USS Lake Champlain. His teaching career began in 1959 at Mississippi State College for Women, and in 1968 he joined the faculty of the history department of East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina. In 1981 Bill co-founded (with Gordon P. Watts Jr.) and served as the rst director of the Maritime History and Underwater Research Program (now the Program in Maritime Studies) at ECU, a position he held until his retirement in 1994. After he retired, he and his wife, Mildred, relocated to Kona, Hawaii, where he served as adjunct faculty for the University of Hawaii. e Stills split their time between Hawaii and North Carolina, and he continued to serve at ECU as professor emeritus.

Dr. Still’s reputation as a scholar in the eld of American maritime and naval history is unparalleled. In addition to his university teaching positions, in the fall of 1989 he was appointed as the Secretary of the Navy’s Research Chair in Naval History at the Naval Historical Center, and served as a member of the Secretary of the Navy’s Subcommittee on Naval History. Dr. Still authored and co-authored dozens of books and publications focused on maritime and naval history from the Civil War through World War II. Up until a few weeks prior to his death, he was actively researching and writing the last installation of his series for the Secretary of the Navy, which began with Crisis at Sea and Victory Without Peace, focused on the US naval force’s

withdrawal following World War I. roughout his professional career, Dr. Still received numerous awards including the Je erson Davis Award and the Bell Wiley Award for the best book in Civil War History, the President Harry Truman Award for Outstanding Research in American History, the Christopher Crittenden Memorial Award for contributions to North Carolina history, the K. Jack Bauer Special Award for contributions to maritime history, and, in 2021, the John Lyman Book Award—along with his co-author, Richard Stephenson—for their book Shipbuilding in North Carolina, 1688–1918 . He was particularly proud to be recognized by the Naval Historical Foundation with the Commodore Dudley W. Knox Medal for Lifetime Achievement in Naval History (2013). A regular presenter at conferences and symposia, he served on the boards of numerous museums.

e graduate maritime studies program that he cofounded and directed has graduated more than 300 students who have gone on to lead the maritime heritage eld . Upon learning of his death, tributes from former students and colleagues came pouring in, remembering his cunning, humor, and maneuvering when it involved cajoling students and colleagues to think outside the box in their approach to furthering the eld of maritime scholarship. He is described as one whose career had a “profound impact,” on the eld and the professionals in it. He was “unwavering,” “good counsel,” “a pioneer,” and “gifted”—even described a ectionately as “curmudgeonly,” a “ball of re,” and a “schemer” with “encyclopedic interests.”

Fair Winds Bill. You are missed, but your legacy continues.

By Deirdre O’Regan, editor, Sea History with contributions from Dr. Still’s family; NMHS trustees William S. Dudley, PhD, retired head of the Naval Historical Center, and Timothy J. Runyan, PhD, professor emeritus and former director of the East Carolina Univer -

sity Program in Maritime Studies; plus numerous former students and colleagues from Hawaii to Europe.

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 7

courtesy the still family

Dr. Bill Still in his o ce at East Carolina University, examining the site plan for USS Arizona.

60th Annual Meeting You’re invited to the...

14-16 April 2023

The Mariners’ Museum and Park • Newport News, VA

is year the National Maritime Historical Society will celebrate its 60th anniversary, and we invite all members to join us for this Annual Meeting milestone the weekend of 14–16 April 2023 at e Mariners’ Museum and Park in Newport News, Virginia. We look forward to gathering to share ideas and reexamine what it means today to preserve maritime history and promote the maritime heritage community. How can we build on this mission and expand our impact? We hope you will help us answer these questions as we share a weekend adventure and chart the Society’s course ahead.

We are thrilled that our host this year is e Mariners’ Museum and Park. ere’s something here for every age and maritime interest —naval heritage and Civil War history, shipwrecks and sunken relics, artifact conservation and ship preservation, underwater archaeology and marine sanctuaries, nature walks around Mariners’ Lake, and even a 60,000-pound propeller that once powered the world’s fastest ocean liner, SS United States, constructed at nearby Newport News Shipbuilding.

On Saturday morning, 15 April, we’ll enjoy a continental breakfast followed by the annual business meeting and presentations from leaders in the maritime and naval heritage community, including Howard H. Hoege, president and CEO of e Mariners’ Museum, Tāne Casserley, a maritime archaeologist with NOAA’s Monitor and Mallows Bay — Potomac River National Marine Sanctuaries, Will Ho man, director of conservation of the USS Monitor Center, Sabrina Jones, director of strategic partnerships at e Mariners’ Museum, and Nate Sandel, director of education and community engagement at Nauticus maritime discovery center. After lunch, we will take guided tours of the museum and the USS Monitor Center which, in partnership with NOAA, is the caretaker of more than 200 tons of artifacts recovered from the wreck of famed Civil War ironclad USS Monitor. Registration for the Saturday annual meeting is $70 per person and includes breakfast, the business meeting, presentations, lunch, and tours.

We invite you to join us a day early in Norfolk on Friday, 14 April, aboard the Victory Rover for lunch and a two-hour cruise on the Elizabeth River and Hampton Roads Harbor. Departing from

Nauticus, home of the battleship USS Wisconsin, we’ll enjoy a front-row seat to the Norfolk Naval Base eet of destroyers, aircraft carriers, submarines, and other vessels while taking in the sights of the harbor. After the cruise, enjoy self-guided tours of USS Wisconsin, one of the largest and last battleships ever built by the US Navy, the Nauticus science and technology center, and Norfolk’s beautiful downtown waterfront. Registration for Friday’s cruise, lunch and visit to the museum and battleship is $60.

On Sunday morning, 16 April, join us for a USS Monitor Center lab tour in the Batten Conservation Complex, one of the most advanced conservation labs of any maritime museum in the world, where you’ll learn about current projects the sta is working on and see conservation in action. Weather permitting, add some outdoor adventure to your day with a self-guided short stroll or long hike around all or part of the award-winning Noland Trail that surrounds Mariners’ Lake. e cost for the Sunday Monitor Center lab tour is $15; the Mariners’ Park and Noland Trail is free and open to the public daily from 6 am to 7 pm

NMHS Chair CAPT James A. Noone, USN (Ret.), and Program Chair Walter R. Brown encourage all NMHS members to join us. For more information and to register, please see the magazine wrapper, visit us at www.seahistory.org/annualmeeting2023, or contact Heather Purvis via email at administrator@seahistory.org or by phone at (914) 737-7878 Ext. 0. Single and full dayregistration options are available, as are sponsorship opportunities. If you can join us as a Donor, Sponsor or Underwriter, we would be most grateful.

NMHS has taken a block of rooms from 13–15 April at the Newport News Marriott at City Center at 740 Town Center Drive for $179/night, plus taxes, including complimentary parking. To make your hotel reservation, call (866) 329-1758 and use the group code “National Maritime Historical Society.” e rate is available until 19 March, or until the reserved block is full.

8 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

(l–r) Nauticus and battleship USS Wisconsin; a team of researchers raises the turret of USS Monitor out of the ocean on 5 August 2002. e turret is currently undergoing conservation at e Mariners’ Museum.

noaa nauticus

Help keep history alive!

Since our founding in 1963, the National Maritime Historical Society has striven to tell the stories, great and small, near and far, that make up the broad panorama of our maritime history. Over the last six decades, hundreds of thousands of readers have discovered in the pages of Sea History magazine a treasure-trove of stories that captivate, connect and enlighten us all about the vital role of our seas, rivers, lakes and bays.

Ensure our maritime history is not lost.

It is more important than ever to bring the lessons of our maritime heritage to young people tomorrow’s maritime leaders. Now you can create a legacy for the next generation of sea service men and women, underwater archaeologists and ocean conservationists, maritime librarians and museum curators, shipwrights and preservationists, marine artists and musicians, ocean racers and tugboat captains, history teachers and writers. Making a legacy gift to the Society is a deeply personal and transformative way to support our lifelong work, helping us to prepare for the future while bolstering the work we do now for our maritime heritage.

Including the National Maritime Historical Society in your will or living trust is one of the most effective ways to provide for the Society’s future while retaining assets during your lifetime. No matter the size of your gift, you’ll be playing an important role in preserving our shared maritime heritage and inspiring future generations. Please email plannedgiving@seahistory.org, or call us at (914) 737-7878 Ext. 0 for more information.

Have you already made a legacy gift?

We hope you will notify us when you have included us in your future planning so that we may thank you and welcome you as a new member of our NMHS Legacy Society.

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 9

Each one of us can make a difference. Together, we make change.

— Senator Barbara Mikulski, 2015 NMHS Distinguished Service Award recipient

Conning Tower, USS Dorado by Georges Schreiber, from the Naval History and Heritage Command collection.

NMHS Legacy Society

YOU’RE INVITED

2023 National Maritime Awards Dinner

e National Press Club • 9 May • Washington, DC

NMHS will ll the National Press Club this spring with its spirited gathering for the 12th National Maritime Awards Dinner taking place on 9 May 2023.

Dinner Chair Samuel F. Byers, along with Founding Dinner Chair Philip J. Webster and NMHS Chair CAPT James A Noone, USN (Ret ), invites you to join us for our annual gala in Washington, DC, as we celebrate three driving forces in the maritime community and their outstanding contributions to our maritime heritage.

Gary Jobson, America’s ambassador of sailing, is the evening’s emcee. An introductory lm by Richardo Lopes, award-winning documentarian and NMHS Vice Chair, will impart the stories of our distinguished honorees. e US Coast Guard Academy Chorale will perform, and the Combined Sea Services Color Guard will present.

In addition, the NMHS Washington Invitational Art Gallery, hosted by acclaimed marine artist Patrick O’Brien, will feature a selection of marine art for sale (preview on pages 16–19). We look forward to welcoming you to this special evening as we pay tribute to our outstanding honorees and meet with members of our exceptional community while we salute our country’s maritime heritage.

Join us! Please contact us to reserve your place. Seating is limited. Visit our website at www.seahistory.org/ washington2023 for more information or to make your reservations. Or call 914 737-7878, extension 0.

Tickets start at $400. Attire is business/cocktail.

Hotel Block: NMHS has reserved a block of rooms at the Hilton Garden Inn at 815 14th Street NW, two blocks from the National Press Club, from 8–10 May at $309 per night (plus applicable taxes). is rate is available until April 17th or until sold out. Visit www.seahistory.org/ washington2023 to make your hotel reservation.

10 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

On the Waterfront: Washington DC in 1899, by Patrick O’Brien.

Congressman Joseph D. Courtney

e Honorable Joseph D. Courtney will receive the Society’s 2023 NMHS Distinguished Service Award in recognition of his continued success and longtime support of the US Navy and the US Coast Guard, securing crucial investments in some of our greatest sources of national strength: service members, innovation and technology, and our allies and partners. We recognize Representative Courtney’s steadfast e orts to deliver funding for US Navy submarine procurement, most recently as part of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2023 and the FY 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act. As Chairman of the House Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee, he championed funding for the production of two Virginia-class attack submarines per year with the Electric Boat division of General Dynamics, as well as Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines. In reversing years of decline at the shipyard, he earned the nickname “Two Sub Joe” for the Virginiaclass subs or, as Mohegan tribal leaders have dubbed him, “Two Iron Fish.” We also salute Congressman Courtney’s work with the Connecticut congressional delegation in obtaining funding for the future National Coast Guard Museum, where Americans will have the opportunity to immerse themselves in Coast Guard life and history through interactive exhibits and galleries designed to celebrate, engage, and inspire.

Oyster Recovery Partnership

Oyster Recovery Partnership (ORP) will receive the 2023 NMHS Marine Conservation Award in recognition of its commitment to the health of the Chesapeake Bay through the successful restoration of oyster populations. A single adult oyster can lter more than 50 gallons of water a day, and over the past 29 years, ORP has planted a staggering 10 billion oysters. e newly established NMHS Marine Conservation Award acknowledges the exemplary work of those who act as stewards of the oceans, seas, and waterways, including e orts to protect, enhance, and restore ecosystems, promote the sustainable management of marine resources, safeguard and improve the well-being of the communities that depend on these resources, and increase public awareness about the importance of protecting marine environments. ORP, with its broad coalition of partners, works to improve the health of the Bay through aquaculture, shell recycling, community awareness, and support of oyster farming and commercial sheries to improve the environment and expand economic opportunities in the Chesapeake region. ORP joins previous NMHS maritime environmentalist award winners David Rockefeller Jr. and Sailors for the Sea, Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Conservation International, and the National Geographic Society.

USS Constitution Museum

e USS Constitution Museum will receive the 2023 Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Maritime Education, presented in recognition of outstanding educational programs that foster greater awareness of our maritime heritage. is year the museum embarks on its 51st year as the educational voice of USS Constitution, the oldest commissioned warship a oat. In honoring the museum and recognizing its president, Anne Grimes Rand, who has expertly guided the organization for over three decades, the Society also celebrates the 225th anniversary of Constitution’ s maiden voyage in 1798 and applauds her newest captain and rst female commanding o cer, CDR Billie J. Farrell, USN. Since 1972 the USS Constitution Museum has interpreted the ship’s remarkable history, collecting, preserving, and curating the artifacts that tell the history of this storied frigate—America’s o cial Ship of State. NMHS recognizes the museum’s contributions to scholarship, its innovative work appealing to a global audience, and its presentation of the stories of our maritime heritage.

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 11

US HOUSE OFFICE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Joseph David Courtney has been instrumental to the sea services community as the US representative for Connecticut’s 2nd congressional district since 2007.

In 2022, Oyster Recovery Partnership planted 950 million oysters and passed the milestone of planting 10 billion oysters over its threedecade history.

OYSTER RECOVERY PARTNERSHIP US NAVY

USS Constitution, the oldest commissioned ship in the United States Navy, sets sail in Boston Harbor in 2014. She is berthed at the Charlestown Navy Yard, across the pier from the USS Constitution Museum.

NMHS Presents the 2023 Maritime Art Gallery

John Paul

at

Head by Patrick O’Brien, 24 x 36 inches, oil on canvas $16,000 John Paul Jones was a complicated man. Hard-charging and brave to the point of recklessness, he was also argumentative and known for his quick temper. When he wasn’t at sea fghting epic battles, he was ashore fghting for his reputation. During the American Revolution, Jones brought the fght to the enemy’s shores. The British considered him a pirate, but to the French, he was a dashing heartthrob. To Americans, he was a hero of liberty. Cruising off the coast of England in the French-built frigate Bonhomme Richard, Jones encountered the British ship Serapis off Flamborough Head. In a long and intense battle, his ship was so damaged that the French captain called to Jones to ask him if he wanted to surrender. It was during this engagement that Jones is said to have shouted his response that would live evermore in US naval lore—“I have not yet begun to fght!” He did go on to win the battle, although his ship was so badly damaged that he had to abandon it and transfer to the British ship. After the war, Jones found himself a warrior without a war. He signed up with Russia and became an admiral in their fght with the Turks. During this period he became entangled in a sex scandal, and a few years later he died suddenly of a kidney problem in a hotel room in Paris. He was 45 years old. PO’B

The National Maritime Historical Society is excited to host the 2023 Maritime Art Gallery at the National Maritime Awards Dinner at the National Press Club in Washington, DC, on 9 May 2023. Under the leadership of acclaimed marine artist Patrick O’Brien and in conjunction with the American Society of Marine Artists, a select group of today’s top marine artists has been invited to participate. New works by Patrick O’Brien, Lana Ballot, Marc Castelli, Laura Cooper, Roger Dale Brown, William R. Davis, Donald Demers, Lisa Egeli, Bill Farnsworth, Nicolas Fox, Palden Hamilton, Kathleen Hudson, Neal Hughes, Michael Karas, Russ Kramer, Richard Loud, Leonard Mizerek, Ed Parker, Sergio Roffo, and William P. Stork are featured in this year’s exhibition.

We hope you will join us at the National Press Club on 9 May for the Society’s gala, where you will have an opportunity to meet some of the artists and view their works; however, you need not attend to participate. Paintings purchased in advance will be displayed as “Sold” at the event. Contact Wendy Paggiotta via email at vicepresident@seahistory.org, or call 914-737-7878, ext. 557 to complete your purchase.

Through the generosity of the artists, 25% of all proceeds will beneft NMHS and is tax-deductible to the buyer. Shipping is included. After the event, the exhibition will continue through the end of May at the Annapolis Marine Art Gallery. (110 Dock Street, Annapolis, MD; www.annapolismarineart.com)

12 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

Jones

the Battle of Flamborough

all images courtesy of the artists

Pictured is a downwind leg from one of the races during the Kennedy Cup Regatta held on the waters of the Chesapeake in October. I was a guest on a coach’s boat to follow the races. Each one of the Navy 44s is crewed by a team from a different college. Doing so equips each team with exactly the same sail inventory, the same hull, and the same rigging. — MC

Seeing a schooner foating by in the soft warm evening light creates such a majestic moment. The scene exudes a sense of calm as the schooner silently catches the breeze along the coast. I was inspired to capture this tranquil moment when the effects of atmospheric light refect on the sails and play on the water and sky. —LM

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 13

Bringing the Wind/USNA Kennedy Cup 2016 by Marc Castelli, 22 x 30 inches, watercolor on paper, $6,850

courtesy of the carla massoni gallery, chestertown , maryland

Twilight Return by Leonard Mizerek, 12 x 24 inches, oil on linen panel, $3,200

USS United States on Patrol by Patrick O’Brien, 16 x 20 inches, oil on panel, $4,000

USS United States was launched in Philadelphia in 1797, one of the original six frigates commissioned by the new Congress to create a new navy for the fedgling United States. She carried 44 guns with a complement of more than 400 men. During the War of 1812, the United States won an important duel with the British frigate Macedonian, thus demonstrating that the upstart American Navy could stand up to the greatest naval power in the world. —PO’B

To view these and additional paintings for sale in this year’s gallery, visit www.seahistory.org/artgallery2023/.

Merlin, 1892, Goelet Cup, Newport, Rhode Island, by Laura Cooper, 15 x 23 inches, oil on canvas, $7,800

Merlin was a schooner yacht built in 1889. Owned by W. H. Forbes and homeported in Boston, she won the Goelet Cup in 1892, which was a competition between the New York Yacht Club and the Eastern Yacht Club. —LC

Light Show, by Bill Farnsworth, 14 x 18 inches, oil on linen, $3,600

This painting was done from a plein air study while I was in New Hope, Alabama. Painting boats tied to a dock can be a challenge due to pilings and adjacent boats often obscuring the subject. Fortunately, my boat’s neighbor was gone, so I had a chance to get the entire boat with wonderful light. —BF

14 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

Celebratingover40yearsof America'sfnestcontemporary marineart.

Joinusforthepremiereofour 19th NationalExhibitionandthe 4th NationalMarineArt Conferencethiscoming SeptemberinAlbany,NY

THE AMERICAN SOCIETYOF

MARINEARTISTS

Painting:WilliamG.Muller, A.J.McAllisterRescuingThyraTorm,1961,oil,24x38(detail) AmericanSocietyofMarineArtists.com

H ISTORIC SHIPS ON A L EE SHORE: Schooners on the Move

“Oh! How she scoons!”

Or something like that. So goes the legend around the coining of the term “schooner,” which was rst built and identi ed as such in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 1713, although there are plenty of works of art from Europe from earlier eras that depict fore-and-aft two-masted vessels. In this installment of Historic Ships on a Lee Shore, we take a look at three historic ships and, happily, we can report that all of them are OFF a lee shore!

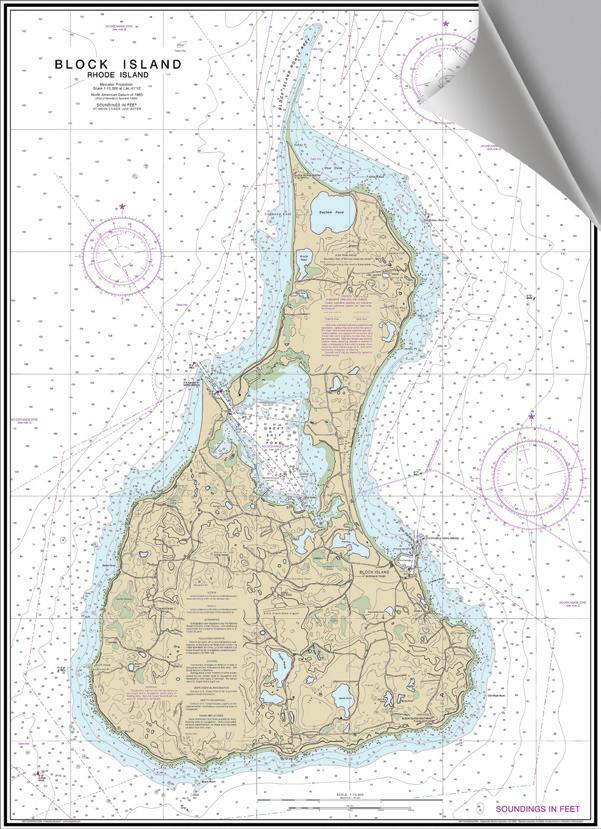

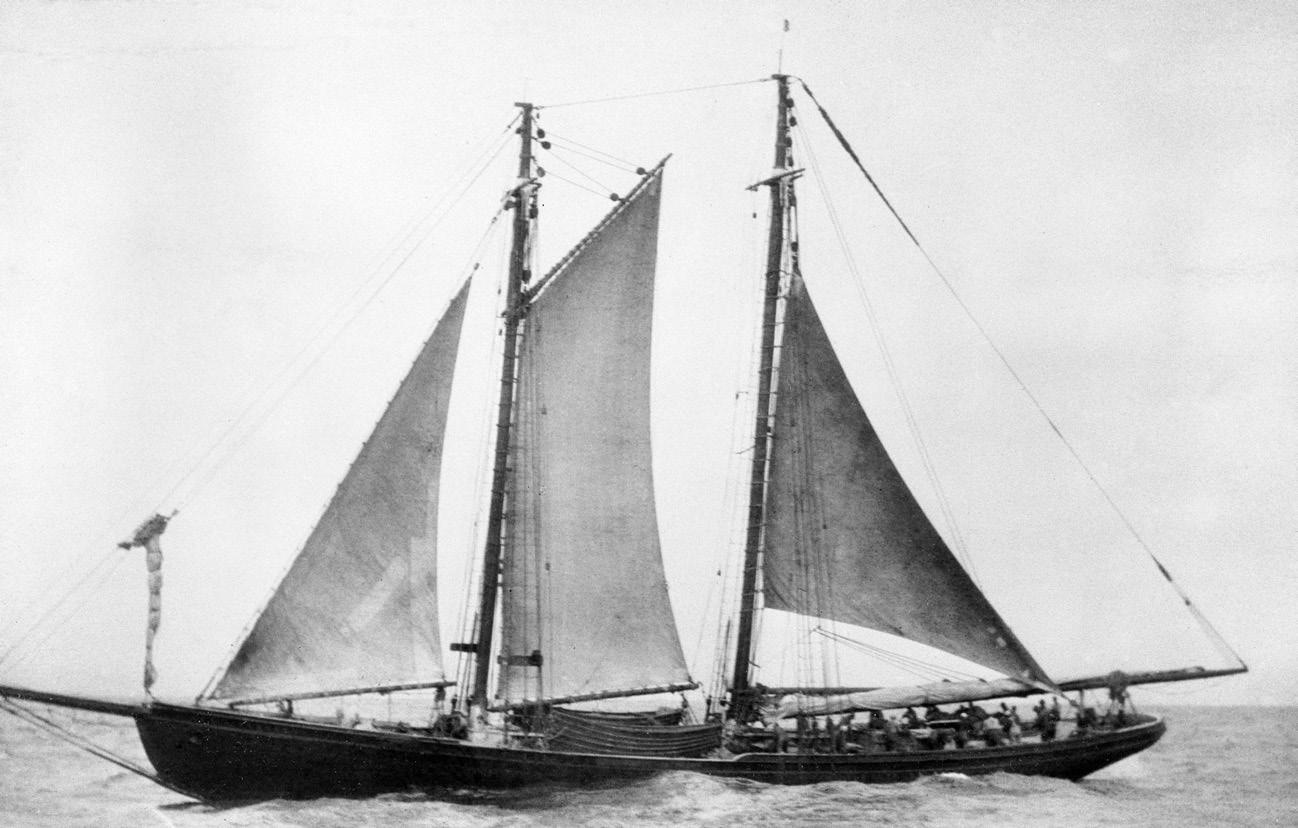

In less than a four-month period this fall, three schooners built in 1885, 1894, and 1921, respectively, were on the move after many years of on-again-o -again e orts to restore them. First was the re-launching of the 1894 schooner Ernestina-Morrissey from Bristol Marine Shipyard in Boothbay, Maine. It then took a couple of months to get her rigged and her sea trials completed, and prep for her triumphant return to New Bedford, Massachusetts, (by way of Massachusetts Maritime Academy) in late November. e o cial vessel of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, ErnestinaMorrissey had not been in home waters since she was towed to Maine in 2015 for a total rebuild. Next came the launch of the 1885 schooner yacht Coronet, which had not been in the water since she was hauled and enclosed in a shed along the Newport, Rhode Island, waterfront, at the International Yacht Restoration School (IYRS). at was in 2004! Finally, in December, the 1921 Essexbuilt shing schooner L. A. Dunton, part of the eet of historic ships at Mystic Seaport Museum, was hauled out for a long-awaited full restoration right next to her berth at the museum.

ese three vessels represent the wide range of uses for a well-built schooner: from a Gilded Age exquisite yacht built to sail across the world’s oceans, to the tough life of a Grand Banks shing schooner, to a vessel adapted to explore the Arctic and later carry emigrants across the Atlantic to New England. We are thrilled to report that they are having new life breathed into them. In the not-too-distant future, the crews of Coronet and Ernestina-Morrissey will be setting sails and getting underway for distant ports. Will the Dunton sail again? “Mystic Seaport has a long tradition of restoring vessels and then taking them to sea,” says Shannon McKenzie, the museum’s vice president of museum operations.

Let’s take a look at each vessel’s current status.

16 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

L. A. Dunton, 1921

Coronet, 1885

schooner ernestina morrissey association

Ernestina-Morrissey, 1894

by Deirdre O’Regan

nathaniel l stebbins collection , historic new england mystic seaport museum

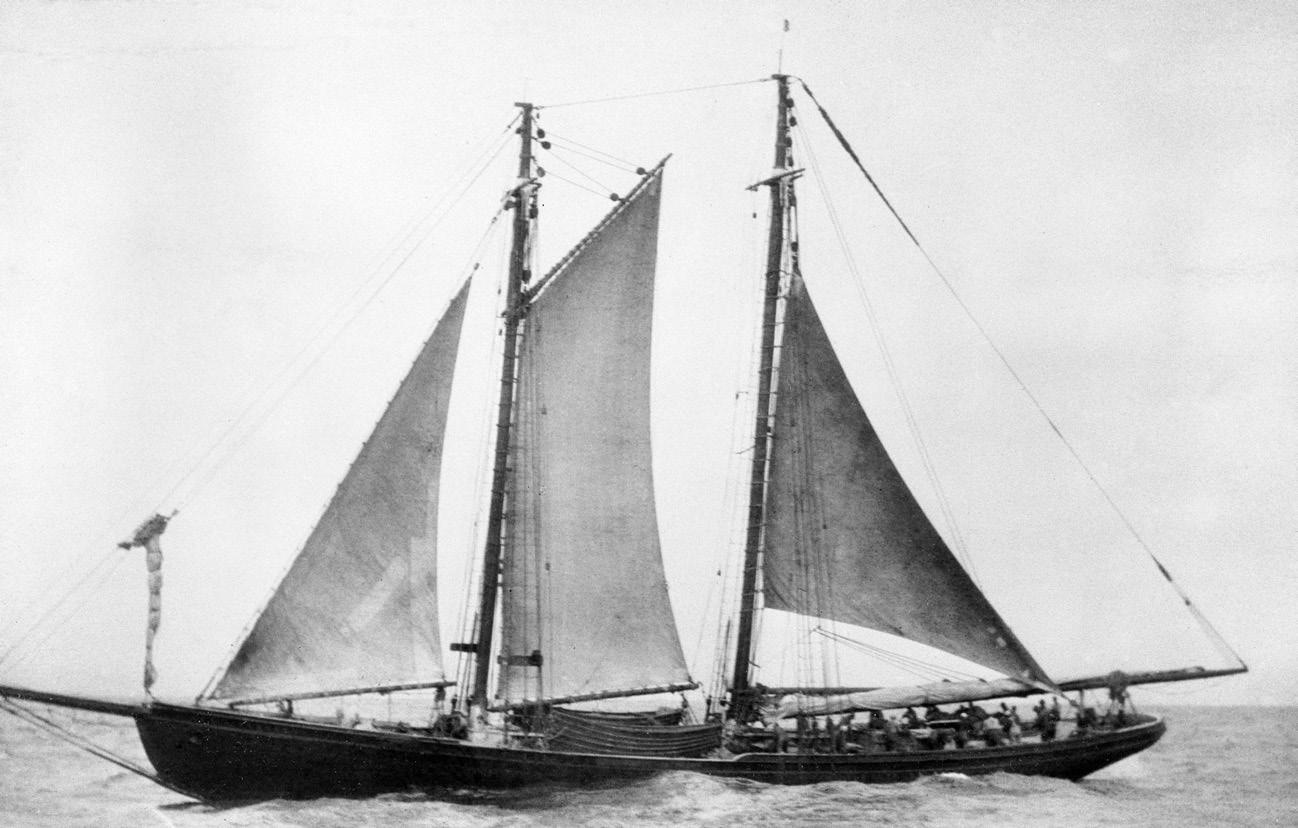

Schooner Yacht Coronet

Arthur Curtiss James was a phenomenally wealthy yachtsman, who by 1898 had logged in more than 45,000 miles at sea in Coronet sailing from Newport, Rhode Island, to Japan and back—all before the opening of the Panama Canal. James sailed not as a mere passenger, but as a self-described Corinthian sailor; he commanded his own vessels and sailed them across the world’s oceans. Coronet was considered the nest and fastest oceangoing yacht at that time.

Coronet was launched in 1885 in Brooklyn, New York, for oil tycoon Rufus T. Bush. e 131-foot schooner was designed for speed, style, and comfort. She could set 8,000 square feet of canvas aloft; down below she was tted with mahogany-paneled staterooms, a marble staircase, stained-glass doors, a cloisonné chandelier, a tiled stove for heat, and a piano in her main saloon. After her rst transAtlantic, Bush o ered $10,000 to any competitor who could beat his new schooner across the Atlantic. Caldwell Colt, owner of the 1866 schooner Dauntless and a fellow New York Yacht Club member, stepped up, and in March 1887 the two schooners left Sandy Hook Light astern and headed out into the Atlantic, bound for Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland. Coronet beat Dauntless by 30 hours, making the run in 14 days, 19 hours, 3 minutes, and 14 seconds. e race got a lot of press at the time, even making the front page of the New York Times. Bush would next take Coronet around the world.

Coronet would go on to greater fame after Arthur Curtiss James became the owner. James wrote in his foreword to the book Corona and Coronet by Mabel

Loomis Todd:

Yachtsmen have been criticized, and in some cases justly, for using their magni cent eet of vessels as mere toys. What an assistance they might be in advancing our knowledge of geography, if their pleasure trips could be turned to some practical account! ... I cannot refrain from urging yachtsmen in general, and those taking ocean trips in particular, to cooperate with the Hydrographic O ce in adding to our knowledge of ocean currents, winds, and other phenomena of the sea.

To this point, he was quite dedicated, and one of his rst major voyages in Coronet was to sail from Newport to Japan in 1896, hosting and funding the Amherst [College] Eclipse Expedition that sought to observe a total solar eclipse.

Coronet would go on to have several owners over her long sailing career, but her long-distance voyages came to a close around World War I. In the 1980s the late marine artist John Mecray stumbled upon her, laid up in Gloucester, Massachusetts; despite the degraded appearance of her hull from outboard, her interior décor was in good condition. Mecray later co-founded the International Yacht Restoration School (IYRS) along with Elizabeth Meyer, and with her encouragement and support, Coronet was eventually brought to Newport to become the de ning project of the school, which welcomed its rst class in 1995.

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 17

Coronet on the day of her re-launch, waiting for the barge crane to get into position.

Stern view of Coronet not long after her arrival at IYRS in 1995.

photo by daniel forster

photo by stephen lirakis

e vessel’s interior furniture, paneling, and xtures were removed and fully documented before going into storage. In 2004, IYRS hauled the hull and placed her in a cradle on the waterfront right outside the school, and the work has progressed in ts and starts since then. In 2006, ownership of Coronet transferred to Coronet Restoration Partners (a partnership between Je rey Rutherford of Rutherford Boat Works and venture capitalist and classic-boat restorer Robert McNeil). e pair had already successfully restored the classic steam yacht Cangarda and understood what they were getting into. Coronet stayed at IYRS and work continued on the hull, done by a combination of IYRS students, alumni, volunteers, and Rutherford and McNeil. In recent years, Coronet was given less and less attention, and when McNeil died from cancer in 2021, IYRS began looking for new owners for the yacht, who could nish the restoration properly.

Mystic Seaport Museum, with an active shipyard well-versed in restoring historic vessels, was one of their rst calls. Mystic’s leadership could not take on ownership of a project of this magnitude in addition to work on their own eet of historic vessels, but referred IYRS to brothers Alex and Miles Pincus, who have restored two other historic schooners at the museum shipyard to convert into restaurant venues in New York City. e team at the museum shipyard holds the Pincuses in high regard, as they have the interest, experience, and means to do the job. e decision was not an easy one, nor one made in haste, but the Pincuses are on board. Once the papers were signed, the Pincuses began working with Mystic Seaport’s team, led by Chris Gasiorek, the museum’s vice president for Watercraft Preservation and Programs, to orchestrate getting the hull from the dock outside IYRS in downtown Newport to the museum campus. Luckily, the hull’s restoration was at the stage where she could be oated and towed to Mystic, a distance of about 35 nautical miles.

After 18 years out of the water,

18 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

(above)

Coronet is airborne as a huge barge crane lifts her from her cradle outside IYRS.

(below) Coronet comes in view of the museum as she is towed past the Mystic River Bascule Bridge on 5 December 2022.

photo by deirdre o ’regan mystic seaport museum

On a cold afternoon on 2 December, a crowd had gathered along the Newport waterfront to watch a 1,000-ton barge crane slowly lift Coronet o her cradle and place her in the water. A few days later, after her hull planking had swelled enough for the trip to Mystic, she was towed by Charlie Mitchell in his tug Jaguar to the museum campus, arriving to further fanfare.

From here, the shipyard crew, in collaboration with the Pincus brothers, will complete Coronet’ s restoration over the next couple of years. e big question many people are asking is if the Pincuses will turn Coronet into a restaurant, like the other vessels they have restored. e brothers assure us that Coronet will be returned to her former glory and operated as a sailing yacht. e

long-term plan? “ e plan is to make a plan,” said Alex Pincus. eir rst goal is to re-create the 1887 transAtlantic race and take some time to enjoy the schooner the way she was meant to be— as a sailing yacht. In the meantime, while Coronet is at Mystic Seaport, the work in the shipyard will take place in full view of museum visitors, as it did for other big ship restoration projects, such as the Charles W. Morgan and May ower II.

(To learn more about Alex and Miles Pincus and their maritime projects and restaurants, visit www.crewny.com. International Yacht Restoration School of Technology and Trades: www.iyrs.edu . Mystic Seaport Museum: www.mysticseaport.org.)

Schooner Ernestina-Morrissey

Launched in 1894 as the E e M. Morrissey and later renamed Ernestina, today the Essex-built schooner goes by ErnestinaMorrissey, and in her 129th year, she isn’t done yet.

She’s been called the “Cape Verdean May ower.” Arctic explorer Captain Bob Bartlett used to call the 156-foot schooner his “little Morrissey.” She’s shed the Grand Banks, sailed to the Arctic from both the Atlantic and the Paci c, conducted survey work for the US Navy in World War II, carried cargo and immigrants to the US from the Cape Verde islands, and taken

hundreds of people to sea on sail training voyages. Today, she is back at her homeport in New Bedford, Massachusetts, after a seven-year absence, during which time her hull has been completely rebuilt in a Maine shipyard. is wasn’t her rst restoration—she’s had several over the course of her long life. She’s been sailed hard and pushed her way through ice oes, run aground, been dismasted, caught on re and scuttled, been raised and repaired. But a wooden ship is never “done,” and in the early 2000s, she fell into disrepair;

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 19

photo by aidan andrews inset photo nps gov habs / haer / hals

(inset) Schooner Ernestina (now Ernestina-Morrissey) under full sail before her recent rebuild. (above) Under power in the Cape Cod Canal, heading for her berth at Massachusetts Maritime Academy in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, on 18 November 2022.

budget cuts prevented the necessary maintenance. In 2005, Coast Guard inspectors identi ed serious degradation of her stem, stern, and transom and pulled the ship’s Certi cate of Inspection (COI). Without it, the vessel could not take people o the dock and thus could generate no income. A crisis was at hand. It took some years, during which time the Commonwealth commissioned surveys, consulted experts, and sought out philanthropists to help with funding. With a lot of e ort and a little luck, a public-private partnership came together with substantial contributions from two gentlemen who learned about the schooner’s story and agreed she had to be saved. Robert Hildreth and the late Gerry Lenfest stepped up, to the tune of several million dollars. e Massachusetts government rea rmed its role as owner and steward, and the ship was sent to Maine for a total restoration. While she was there, a new management plan was conceived and put in place by which the ship will be managed and operated by Massachusetts Maritime Academy (MMA) to train its cadets, with the agreement that she will also spend 25% of her time in New Bedford, her decades-long homeport, where she has a dedicated following. In addition to training MMA cadets, future programming will involve youth programs and public daysails. Plans are still coming together.

Ernestina-Morrissey’s captain, Ti any Krihwan, hosts Prime Minister José Ulisses Correia e Silva, Republic of Cabo Verde, onboard the schooner on 17 December 2022. Correia e Silva traveled to New Bedford to participate in the o cial homecoming event.

and politicians of every stripe participating to applaud the achievement and pledge their support.

e schooner Ernestina-Morrissey was nally relaunched on 30 August 2022 and returned to New Bedford under her own power (but no sails yet) with a new captain in command and a full crew of professional mariners. On 17 December, a grand homecoming event took place in New Bedford, with dignitaries

What’s next?

e schooner is currently at her berth in New Bedford over the winter months. She still has to pass her Coast Guard inspection and other work needs to be completed. In March, she will get underway (with just crew until she has her COI in hand) and head to the Gulf Coast to participate in the Tall Ships Challenge series, organized by Tall Ships America. After that she will return to New England waters in June and July. Check the MMA website for updates: www.maritime.edu/ eet/ernestina. Tall Ships Challenge information is at: www.tallshipsamerica. org/tall-ships-challenge/.

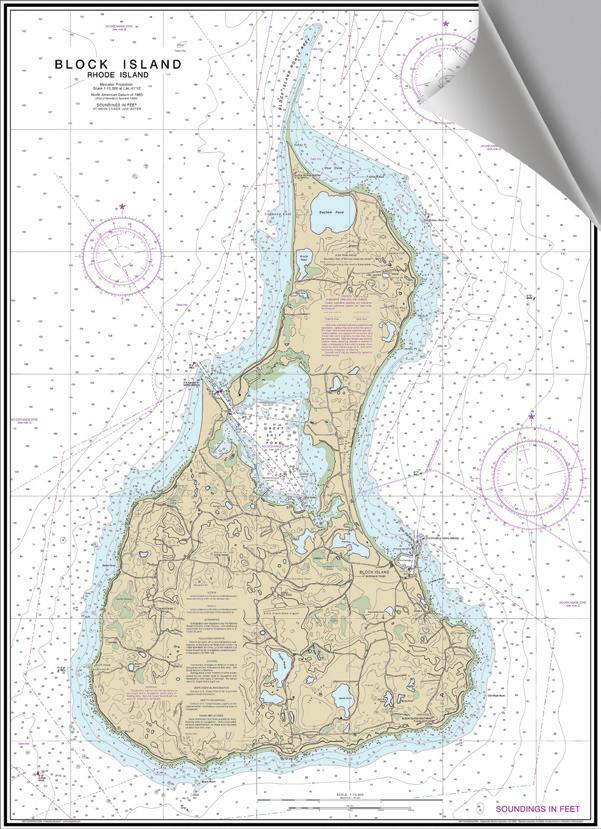

Schooner L. A. Dunton

On20 December 2022, the schooner L. A. Dunton, a National Historic Landmark, was hauled by crane (similar setup to Coronet’s launch) at her home at Mystic Seaport Museum to undergo a full, multi-year restoration. Like her older sister ErnestinaMorrissey, the 101-year-old L. A. Dunton was built in Essex, the tiny Massachusetts hamlet that built and launched more than 4,000 schooners in its heyday. e Dunton shed the Grand Banks for cod at a time when dory shing from sailing vessels was on the way out. Her builders were not unaware of this trend, however, and although she was originally built to operate under sail power alone, she was constructed with a shaft log and engine bed to accommodate the addition of a diesel engine later.

e 123-foot wooden schooner was designed by omas F. McManus, a sh merchant turned naval architect, who designed

L. A. Dunton with all sail set, ca. 1920s.

20 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

massachusetts maritime academy

nps gov

500 schooners with an eye for performance and safety, a characteristic Grand Banks schooners were not especially known for. Speed, yes; safety—not so much. She was named for a well-known Boothbay sailmaker, and in her rst year of shing she landed 197,000 pounds of fresh halibut, 68,000 pounds of salt cod, and 3,000 pounds of fresh cod. A 100HP Fairbanks, Morse and Co. C-O engine was installed in 1923, among other modi cations.

e Dunton’s shing career lasted until 1960, when new owners started using her to haul cargo, mainly between ports in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. In 1963 she was sold to the Marine Historical Association of Mystic, which would become Mystic Seaport Museum. e museum did not then have its own shipyard, so the 42-year-old schooner was sent to a commercial shipyard in nearby New London, Connecticut, where her stern was rebuilt

and the whaleback house that had been added during her shing career was removed. ose who restore historic vessels have to make hard choices as to what era in a vessel’s history and con guration it should be returned to. In the Dunton’ s case, the team at Mystic Seaport chose the years 1922–23, the period in the ship’s history before she was equipped with an engine.

Mystic Seaport established the Henry B. duPont Preservation Shipyard in 1972 and the Dunton was hauled at the museum campus for the rst time in 1975. Since she became a museum ship, her engine has been removed, her stern has been restored to the correct appearance, her deck beams, deck planking, and frames have been replaced, and the topsides have been replanked, but the vessel has never undergone a full restoration until now. With the shipyard crowded with vessels from the museum eet and visiting ships there for repairs and restoration work, the museum built a new concrete pad upon which to place the schooner for this restoration period on the north end of the shipyard. Today, visitors can view the ship out of the water while work is being done. ose interested in helping fund the restoration are encouraged to contact the museum advancement department at advancement@mysticseaport.org. (www.mystic seaport.org)

her upcoming restoration work at Mystic Seaport’s Henry B. duPont Preservation Shipyard.

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 21

photo by charley seavey

L. A. Dunton being hauled by crane to be placed on the wharf for

mystic seaport museum

All Hands on Deck: Storms, Turmoil, and a Rompin’ Good Sail Aboard the Tall Ship Rose

Iwas blindsided when Tony o ered me a paid crew spot aboard the lofty square rigger, as I had only just met him ten minutes before. I was there because I was broke. Casey, my former captain, told me to go down to the ship at her berth in Newport to ask for some day work. I thought I’d spend my morning cleaning bilges or chipping rust; instead I was presented with an opportunity to sail to California to make a Hollywood movie. Tony was the chief mate of the tall ship Rose, a modern re-creation of an 18th-century British warship. e ship had been purchased earlier that year by 20th Century Fox to star in a new lm directed by the acclaimed Academy Award-winning director Peter Weir, based on the bestselling books by Patrick O’Brian. e movie would be called Master and Commander: Far Side of the World and star Hollywood A-listers Russell Crowe as Jack Aubrey and Paul Bettany as Stephen Maturin. Rose was in Newport, Rhode Island, and our job was to get the ship to San Diego in time to be transformed into “HMS Surprise ” for the lm production, which was set to begin in the summer of 2002.

by Will Sofrin

Truthfully, despite the Hollywood allure, I was not thrilled about the idea of working aboard a tall ship. I had a preconceived plan for becoming a professional sailor that was limited to only working on classic sailing yachts cruising from one luxurious destination to the next. I had just returned from a summer in the Mediterranean, where I worked onboard the 12-meter yacht Onawa for the America’s Cup Jubilee, followed by the Prada Classic Yacht Challenge. A recent graduate of the International Yacht Restoration School (now IYRS School of Technology and Trades), I had convinced myself that my newly acquired skills, along with my experience aboard Onawa, would be a guaranteed ticket to success. Reality set in when I got back from the Med, and it only took a few days for me to realize that landing a crew position on a yacht headed for the Caribbean in late October was going to be next to impossible, as all those jobs had been lled earlier in the fall and those vessels had already left for the winter.

I didn’t know much about squareriggers, other than having attended a few tall ship festivals as a kid. Rose was a full-

rigged ship, built in 1969 by Smith & Rhuland Shipyard in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, commissioned by John Millar for the 1776 Bicentennial celebration for $300,000 (roughly $2.4 million in 2022). Millar hired naval architect Philip Bolger to develop a set of plans for a modern recreation of the 1757 HMS Rose but designed to meet nancing and modern safety requirements. e 20th-century version of Rose was 179 feet long (LOA), with a 30.5foot beam, and the top of her tallest mast towering 130 feet above the water.

Millar’s vision for the ship was never fully realized, and after the Bicentennial celebrations concluded, Rose fell into disrepair because the cost of maintaining her outweighed her ability to generate revenue. In 1984, Kaye Williams purchased Rose and relocated her to Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he owned and operated a marina and tourist venue. Williams put together a team that included sailing ship master Captain Richard Bailey to repair the ship and restore her to seagoing condition. Following an extensive re t, Rose was inspected and certi ed by the US Coast Guard, becoming the only Class-A Sailing School Vessel in the United States. Rose went on to serve as an educational platform o ering a variety of sail training programs to the public, until being acquired by 20th Century Fox in the spring of 2001.

I began working as one of the ship’s carpenters at the start of November. To prepare for our voyage from Atlantic to Paci c, Rose was hauled out at a Newport shipyard, where twin Caterpillar 3406 diesel engines were installed in her engine room and the hull was re-caulked below the waterline. We replaced several hull planks and added a section of copper sheathing below the waterline up near the bow. My work was focused on rebuilding

22 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

Best-selling author Patrick O’Brian (center) with Rose’s captain, Richard Bailey, onboard the replica ship in New York City in 1995 for a press event to promote e Commodore, the 17th installment of his hugely popular Aubrey-Maturin series.

courtesy the williams family

the mast partners for the foremast and applying the copper plating. We were working long days, hoping to be ready to depart at the beginning of January. As our crew numbers grew, so did the to-do lists. e workdays got longer and the air got colder, but the hard, grimy work helped us learn how to work together as a team. We were a melting pot of personalities, and not everyone got along, but we were all there for a greater cause, which outweighed our di erences. It was universally understood that order had to come rst on our ship if we were to succeed in getting the ship ready for sea and then sailing her on a long-distance voyage in winter.

We departed on ursday, 10 January 2002, with a crew of thirty. We hadn’t had an opportunity to have a shakedown sail, let alone any sail training before we got underway. We would have to learn by doing, but at least half the ship’s company had considerable experience sailing Rose, or other similar traditionally rigged vessels.

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 23

tsuneo nakamura / volvox inc / alamy

e replica of the 1757 HMS Rose was purchased in 1984 by Kaye Williams, owner of Captain’s Cove in Bridgeport, Connecticut. He did an extensive rebuild of the ship and was able to secure her Coast Guard certi cation as a sailing school vessel. (below) Rose ying along on a downwind leg.

courtesy the williams family

e ship’s company was broken up into three watches; I was on A-Watch, led by Tony, the mate. As we left Narragansett Bay astern and peeked out into the North Atlantic, we set staysails and conducted safety drills. Afterwards, those not on watch went below to get some rest and get warm.

at rst night was bitter cold, but we tolerated it well enough, knowing that we would be crossing the Gulf Stream and into milder temperatures in about two days. e following day, we set the square sails for the rst time and secured the engines. Despite the promise of warmer weather, we soon found ourselves sailing through a gale. I loved every second of it. Rose powered through the frothy sea under sail like a freight train charging across the tundra.

e next day, the weather had eased but the ship’s engines would not start, as they were hydrolocked. Hydrostatic lock, also known as hydrolock, is when a uid has entered the engine and prevents the pistons from reaching the top of their stroke. As a result, the engine cannot complete its cycle. Our engineer worked feverishly to get the engines back online while the rest of the crew crawled around the ship in rough seas, preparing for another spell of foul weather we were approaching. e day was tense. By the afternoon the engines were running again, but that didn’t seem to ease the mood. I was naïve and not wor-

ried about the approaching front because of how easily we had weathered the gale the day before. Boy was I wrong!

I was assigned to boat-check at 1000. Waves were breaking over the foredeck, so it was deemed too dangerous for anyone to stand anywhere forward of the mainmast on the weather deck. Still, boat-check had to go up to the bow and climb down into the forepeak to make sure the pumps were working. Getting to the forepeak required a strategically timed assault to absorb the occasional waves breaking over the deck. Once on the bow, I lifted the hatch carefully so neither waves nor wind could possibly catch it, either ripping it o or shattering it. A loss of the hatch would create an opportunity for water to ood the interior of the ship from the deck, potentially overwhelming the pumps and sinking the ship. I waited for the perfect moment, lifted the hatch, scurried into the small thirty-by-thirty-inch opening, and closed the hatch behind me.

Now I had a front-row seat to all the violence our ve-hundred-ton ship was charging through. ere was no electricity; the only source of light was my trusty Maglite. e darkness, mixed with the slamming motion of the ship, was compounded by the deafening blows of the

bow hitting never-ending walls of water. Moving as fast as possible, I climbed down the rst ladder, holding on tight because every impact felt like a grenade going o . I waited for the right moment, jumped o the ladder, lifted the small, grated hatch beneath me, and climbed down into the lowest section of the forepeak. is is where things got truly terrifying. I was in the bow of a ship, which was shaped like a bathtub. e rounded bow acted more like a spoon pushing against the force of the water instead of a knife cutting through it. e original HMS Rose would have had canted frames, meaning that the frames were oriented perpendicular to the planking of the hull. e frames in the new Rose, however, were oriented perpendicular to the keel, the centerline of the ship. is orientation put them at an acute angle relative to the planking of the hull. is orientation destabilized the hull up forward, which caused the bow to ex tremendously. As I crouched there in the forepeak, the exing was happening so much that I could see daylight coming through the seams of the planks. Seeing it in person was terrifying; you should never see light through plank seams.

Gallons and gallons of water rushed into the forepeak through the opening seams every time the bow buried into a wave; it was like standing in a car wash. e pumps were running, but this volume of water was almost more than they could handle. If the pumps went down, we went down.

By this point, we were near the outer limits of a region known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic.” We were more than three hundred miles o shore, beyond reach of any US Coast Guard land-based air rescue, which likely would have been the USCG MH-60 Jayhawk medium-range recovery helicopter. Even if the Jayhawk could have reached us, they would have been able to rescue only six people at a time. Had this approach been feasible and resources available, it would have required multiple helicopters and rescues over an extended period. Situationally dependent, the Search and Rescue (SAR) controller would have sought additional air resources from the Department of Defense (DOD), in-air refueling capabilities, and helicopters that

24 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

photo by k blythe daly

Captain Richard Bailey (left) with the author at the helm, enjoying a brief moment of calm seas and warm temperatures in the Gulf Stream.

may have been able to support a scenario that included thirty people. Again, situationally dependent, the Coast Guard also would try to seek assistance from large merchant or military vessels using the Automated Mutual-Assistance Vessel Rescue System (AMVER). Rescue by any smallcraft pleasure vessels would have been ruled out because of the size of our crew.

ere is a long history of boats sinking near the Graveyard of the Atlantic due to the erce weather that can develop. An estimated ve thousand ships have gone down in that region in the past ve hundred years. I personally know of two vessels lost there in the years after my passage on Rose

e rst, in 2007, was a fty-four-foot sailboat named Flying Colours, which was lost at sea. Her last known position was within two hundred miles of where we entered the storm. e captain, Trey Topping, was my friend. He was also Casey’s nephew, and he was a good sailor. He and the other three

souls on board all disappeared. Nobody knows what happened to them. e search and rescue area was 5,440 square miles.

en, in 2012, a similar ship to Rose, the replica of HMS Bounty, sank in Hurricane Sandy. Her last known position was around one hundred miles west of where we entered the storm. Fourteen crew survived after being rescued by the Coast Guard. Deckhand Claudene Christian was recovered but declared dead on arrival, and the ship’s captain, Robin Walbridge, was lost at sea.

Abandoning ship is the very last thing anyone should ever do. Even if the ship starts to sink, you need to stay on board for as long as possible. e ship is your island, and you do everything you can to keep it oating. Nevertheless, we counted and prepared survival suits, lights, life jackets, and life rafts.

Around 1030, the starboard side of the fores’l started to come loose. It didn’t take

more than a few seconds for the sail to begin ailing around like a bedsheet on a clothesline in a tornado. It was evident that if left alone, the sail would shred itself to pieces and possibly cause a dismasting. e wind had eased a bit and was hovering between thirty- ve and fty knots and gusting past sixty knots. We were in between squall lines, which o ered us a brief opportunity to contain the sail before the wind picked back up. e only option was to climb aloft and shimmy out to the end of the yard to wrestle the sail into obedience. For some reason, Tony grabbed me and told me to go aloft with him.

I followed Tony forward to the base of the foremast shrouds. e sail was fty feet up in the air. e waves we were climbing were still topping out at twenty to thirty feet. Falling from where we needed to get to could end up being a drop of seventy to eighty feet. I read somewhere that window cleaners know falling from a

SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023 25

Rose’s blu -shaped bow was ideal in a downwind leg but made things di cult pounding in head seas, putting excessive stress on the hull planking up forward during the height of the storm.

photo by scott hamann

height above ve stories, or fty feet, is fatal. As far as I knew, only one person had ever fallen from the rig of Rose, and it happened at the dock in New York Harbor.

e chief mate, who was on deck, saw it happen and broke her fall by body-checking her into the water before she could hit the deck. She fell from a height of fty feet and cracked some ribs and a wrist but lived.

Before sailing on Rose, any work I performed aloft was always done from a bosun’s chair, which is generally how people go up a mast today. A bosun’s chair is a seat-like harness that is usually suspended from a halyard for the purpose of doing work aloft in the rig. Modern sailors don’t climb aloft to set or strike sail; in fact, most modern boats don’t have any means to climb the rig. at is because free-climbing up a mast in the middle of the ocean in the middle of a storm is a horrible idea....

We began our ascent by climbing out and around to the windward side of the foremast shrouds. I was now outside of the boat, standing over the water on the ratlines. I knew time was precious and moving slowly would only worsen the situation. Using the foremast as a line of sight, I started climbing while keeping my eyes locked forward on the mast to prevent me

from looking down at the frothy waves below. We were not wearing lifejackets, and the likelihood of successfully being rescued from the water after falling from the rig was almost nonexistent.

e thrashing of the ship was causing the shrouds to tighten and slack quickly and randomly. I carefully put one hand over the other as I climbed, making sure to wrap my arms hard around the shrouds when the ship buried itself into a wave.

ose moments made the rig shudder like we were slamming into a brick wall. en the next wave would pick us back up, and we would surge ahead again until we were thrown back into another trough. We were being absolutely pounded.

Experiencing the violence of the storm from the deck was rough, but it was nothing compared to what it was like up in the rigging. e intensity of the wind grew, as did its roar, sounding like an express subway train rushing past a station. I could feel the stinging pellets of rain through my foulweather gear, hitting me harder and harder the higher I climbed. I felt like a target at an air ri e shooting range. On deck, the ship was rolling from one side to the other. From aloft, we were being thrown sixty to eighty feet across the sky from side to side,

every four to ve seconds. e random rolling of the ship was like riding a ftyfoot-tall metronome that couldn’t keep a rhythm.

Climbing up the shrouds was the easy part. Getting out to the sail was dodgier because I needed to take a small leap of faith o the rigging to get onto the yard and then out to the sail. Waiting for the right moment, I lunged onto the footrope while grabbing hold of the yard and began shimmying out toward the end. I was rst out on the yard, a situation I had never been in. Walking along a footrope was like using a long jump rope as a bridge. I held on for dear life, balancing my weight so my movements would be in sync with Tony’s when he climbed on behind me. We were standing on the same footrope, and any movement I made was felt by him. Laying on a yard in this kind of weather was the very de nition of insanity.

We reached the ogging sail, and I tried to grasp the task before me. Seeing the sail ghting to be released up close was far di erent from seeing it from the deck. ere was no time to get comfortable. e wet sail was lling with rapid bursts of air and thrashing ferociously. It terri ed me. My plan was to jump onto the sail as if I

26 SEA HISTORY 182, SPRING 2023

courtesy andrew emmons

Will Sofrin making his way back from the bow after inspecting the forepeak in the height of the storm.

was trying to take control of an angry bull at a rodeo. If I did it wrong, I could fall, taking Tony with me. e jerk felt by Tony from my lanyard trying to stop my fall to the deck would make it near impossible for him to maintain his footing. We had our safety harnesses clipped to the back rope with the lanyard, but our harnesses were called “backbreakers” for a reason.

I looked over my left shoulder to see Tony just a few feet inboard of my position. I shouted at the top of my lungs, “How should I do this?”