"1har she is, Cap'n! I've trained the glass on 'er. 'Tis Minot's Light, for sure." "Eh, wot? And the faint glow up ahead?" "That'd be Boston , sir." "Then we'll be saved, if you lads tend your helm." Inland canals burgeoned in Europe and the United States during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but they were mostly pick-and-shovel affairs suitable only for shallow, towed barges. Of necessity, barges had to be loaded and unloaded to larger vessels to place goods into oceanic trade. Repeated handling added expense. As compelling as it was to bypass dangerous capes, or entire continents in the case of the Suez and Panama Canals, channels large enough to accommodate ships had to wait until ea rth-moving and lock-building technology had significantly improved. It took affo rdable steel, m ade avai lable in 1855 by the Bessemer process, and mobile earth movers and dredges powered by steam engines befo re ship-worthy canals were built. The Suez Isthmus had seen modest hand-built efforts in ancient times, but the need to acco mmodate oceangoing vessels had grown by the nineteenth century. The openin g of the Suez Ca nal in 1869 was a huge breakthrough for oceangoing ships. Africa, the second largest continent, added many thousands of miles to trade routes betwee n Europe and Asia. Engineering obstacles were slight in compa rison to benefits, especially because the dig went through low-lying sa nds. The Kiel Ca nal across Jutland from the Baltic to North Seas was made big enough for ca rgo ships by 1895, and enlarged to allow for battleships by 1914. The Kiel Canal is now the world's busiest artifici al waterway, carrying more than 43, 000 vessels a year, not counting small craft. Cape Cod extends about sixty-five miles from Southeastern Massachusetts into the Atlantic- not so far as Jutland into the North Sea, nor posing such a barrier between Europe and Asia as the continent of Africa, or a wall between the Atlantic and Pacific like the Americas. Even so, the northeastern United States has a busy coastline, and the navigational h azards of the Cape had proven fatal to thousands since Europeans first visited its shores. The outer Cape itself is nearly featureless for half its length and forms a dangerous lee shore in northeast storms. From a ship's lookout, the convex shape forms an unusual, receding curve that throws off judgment of its true dimensions. Because Cape Cod 's elbow is so low-lying, the safe ch a nnels between the Cape and Nantucket Shoals are particula rly hard to spot, and the risk is especially dire. Even in good visibility, the dunes of C hatham and Monomoy Island are so low that distances are hard to estimate, even for the most experienced of mariners. Pollack Rip C hannel, which cuts from the Atlantic Ocean into Nantucket Sound, is beset by swift currents and flanked by shoals. ''Aye, Cap'n, we're almost past 'er," cries the lookout. "Oh no we aren't,'' the Captain might say. "There's a nother two leagues, I can see them now. And breakers callin g our name. So set another jib, ye swabs, and make for deeper water. W e're losing ground."

12

~-~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~---.

"

~

8

~

8 0 8

~

:i ~

~ 2 g

;: 0

8 " 0 z

0

~

u

z ~

~

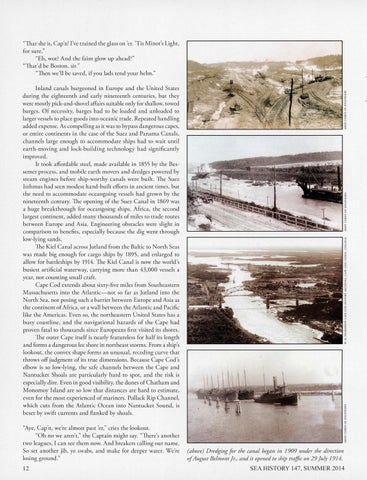

(above) D redging for the canal began in 1909 under the direction ofAugust Belmont Jr. , and it opened to ship traffic on 29 July 1914.

SEA HISTORY 147, SUMMER 2014