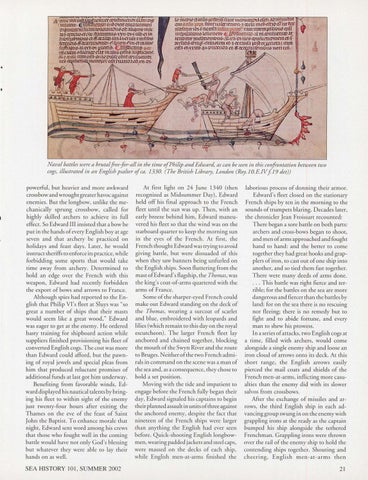

Naval battles were a brutalfree-for-aff in the time ofPhilip and Edward, as can be seen in this confrontation between two cogs, iffustrated in an English psalter of ca. 1330. (The British Library, London (Roy. I 0.E.IVf 19 det))

powerful, but heavier and more awkward crossbow and wrought greater havoc against enemies. But the longbow, unlike the mechanically sprung crossbow, called for highly skilled archers to achieve its full effect. So Edward III insisted that a bow be put in the hands of every English boy at age seven and that archery be practiced on holidays and feast days. Later, he would instruct sheriffs to enforce its practice, while forbidding some spans that would take time away from archery. Determined to hold an edge over the French with this weapon, Edward had recently forbidden the export of bows and arrows to F ranee. Although spies had reported to the English that Philip VI's fleet at Sluys was "so great a number of ships that their masts would seem like a great wood," Edward was eager to get at the enemy. He ordered hasty training for shipboard action while suppliers finished provisioning his fleet of converted English cogs. The cost was more than Edward co uld afford, but the pawning of royal jewels and special pleas from him that produced reluctant promises of additional funds at last got him underway. Benefiting from favorable winds, Edward displayed his nautical talents by bringing his fleet to within sight of the enemy just twenty-four hours after exi ting the Thames on the eve of the feast of Saint John the Baptist. To enhance morale that night, Edward sent word among his crews that those who fought well in the coming battle would have not only God's blessing but whatever they were able to lay their hands on as well.

SEA HISTORY 101 , SUMMER 2002

At first light on 24 June 1340 (then recognized as Midsummer D ay), Edward held off his final approach to the French fleet until the sun was up. Then, with an early breeze behind him, Edward maneuvered his fleet so that the wind was on the starboard quarter to keep the morning sun in the eyes of the French. At first, the French thought Edward was trying to avoid giving battle, but were dissuaded of this when they saw banners being unfurled on the English ships . Soon fluttering from the masrofEdward's flagship, the Thomas, was the king's coat-of-arms quartered with the arms of F ranee. Some of the sharper-eyed French could make out Edward standing on the deck of the Thomas, wearing a surcoat of scarlet and blue, embroidered with leopards and lilies (which remain to this day on the royal escutcheon). The larger French fleet lay anchored and chained together, blocking the mouth of the Swyn River and the route to Bruges. Neither of the two French admirals in command on the scene was a man of the sea and, as a consequence, they chose to hold a set position. Moving with the ride and impatient to engage before the French fully began their day, Edward signaled his captains to begin their planned assault in uni ts of three against the anchored enemy, despite the fact that nineteen of the French ships were larger than anything the English had ever seen before. Quick-shooting English longbowmen, wearing padded jackers and steel caps, were massed on the decks of each ship, while English men-at-arms finished the

laborious process of donning their armor. Edward's fleet closed on the stationary French ships by ten in the morning to the so unds of trumpets blaring. Decades later, the chronicler Jean Froissart recounted: There began a sore battle on both pans: archers and cross-bows began to shoot, and men of arms approached and fought hand to hand: and the better to come together they had great hooks and grapplers of iron, to cast out of one ship into another, and so tied them fast together. There were many deeds of arms done. .. . This battle was right fierce and terrible; for the battles on the sea are more dangerous and fiercer than the battles by land: for on the sea there is no rescuing nor fleeing; there is no remedy but to fight and to abide fortune, and every man to shew his prowess . In a series of attacks, two English cogs at a time, filled with archers, would come alongside a single enemy ship and loose an iron cloud of arrows onto its deck. At this short range, the English arrows easily pierced the mail coats and shields of the French men-at-arms, inflicting more casualties than the enemy did with its slower salvos from crossbows. After the exchange of missiles and arrows, the third English ship in each advancing group swung in on the enemy with grappling irons at the ready as the captain bumped his ship alongside the tethered Frenchman. Grappling irons were thrown over the rail of the enemy ship to hold the contending ships together. Shouting and cheering, Engli sh m en-at-arms th en

21