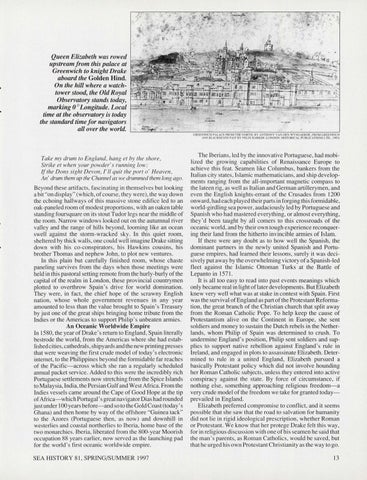

Queen Elizabeth was rowed upstream from this palace at Greenwich to knight Drake aboard the Golden Hind. On the hill where a watchtower stood, the Old Royal Observatory stands today, marking 0 °Longitude. Local time at the observatory is today the standard time for navigators all over the world. GREENWICH PALACE FROM T HE NORT H. BY ANTHONY VAN DEN WYNGAERDE, FROM GREENWICH AND Bl.ACKHEATH PAST BY FELI X BA RK ER (LONDON : HISTORICAL PUBLICATIONS LTD., 1993)

Take my drum to England, hang et by the shore, Strike et when your powder's running low; If the Dons sight Devon,/' ll quit the port o' Heaven , An' drum them up the Channel as we drummed them long ago. Beyond these artifacts, fascinating in themselves but looking a bit "on display" (which, of course, they were), the way down the echoing hallways of this massive stone edifice led to an oak-paneled room of modest proportions , with an oaken table standing foursquare on its stout Tudor legs near the middle of the room. Narrow windows looked out on the autumnal river valley and the range of hills beyond, looming like an ocean swell against the storm-wracked sky. In this quiet room, sheltered by thick walls, one could well imagine Drake sitting down with his co-conspirators, his Hawkins cousins, his brother Thomas and nephew John, to plot new ventures. In this plain but carefully finished room, whose chaste paneling survives from the days when those meetings were held in this pastoral setting remote from the hurly-burly of the capital of the realm in London, these provincial countrymen plotted to overthrow Spain ' s drive for world domination . They were, in fact, the chief hope of the scrawny English nation, whose whole government revenues in any year amounted to less than the value brought to Spain ' s Treasury by just one of the great ships bringing home tribute from the Indies or the Americas to support Philip's unbeaten armies.

An Oceanic Worldwide Empire In 1580, the year of Drake ' s return to England, Spain literally bestrode the world, from the Americas where she had established cities, cathedrals, shipyards and the new printing presses that were weaving the first crude model of today's electronic internet, to the Philippines beyond the formidable far reaches of the Pacific-across which she ran a regularly scheduled annual packet service. Added to this were the incredibly rich Portuguese settlements now stretching from the Spice Islands to Malaysia, India, the Persian Gulf and West Africa. From the Indies vessels came around the Cape of Good Hope at the tip of Africa-which Portugal's great navigator Dias had rounded just under JOO years before-and so to the Gold Coast(today's Ghana) and then home by way of the offshore "Guinea tack" to the Azores (Portuguese then , as now) and downhill in westerlies and coastal northerlies to Iberia, home base of the two monarchies. Iberia, liberated from the 800-year Moorish occupation 88 years earlier, now served as the launching pad for the world 's first oceanic worldwide empire. SEA HISTORY 81, SPRING/SUMMER 1997

The Iberians, led by the innovative Portuguese, had mobilized the growing capabilities of Renaissance Europe to achieve this feat. Seamen like Columbus, bankers from the Italian city states, Islamic mathematicians, and ship developments ranging from the all-important magnetic compass to the lateen rig, as well as Italian and German artillerymen, and even the English knights-errant of the Crusades from 1200 onward, had each played their parts in forging this formidable, world-girdling sea power, audaciously led by Portuguese and Spanish who had mastered everything, or almost everything, they ' d been taught by all comers to this crossroads of the oceanic world, and by their own tough experience reconquering their land from the hitherto invincible armies of Islam. If there were any doubt as to how well the Spanish, the dominant partners in the newly united Spanish and Portuguese empires, had learned their lessons, surely it was decisively put away by the overwhelming victory of a Spanish-led fleet against the Islamic Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. It is all too easy to read into past events meanings which only became real in light of later developments. But Elizabeth knew very well what was at stake in contest with Spain. First was the survival of England as part of the Protestant Reformation, the great branch of the Christian church that split away from the Roman Catholic Pope. To help keep the cause of Protestantism alive on the Continent in Europe, she sent soldiers and money to sustain the Dutch rebels in the Netherlands , whom Philip of Spain was determined to crush. To undermine England's position, Philip sent soldiers and supplies to support native rebellion against England's rule in Ireland, and engaged in plots to assassinate Elizabeth. Determined to rule in a united England, Elizabeth pursued a basically Protestant policy which did not involve hounding her Roman Catholic subjects, unless they entered into active conspiracy against the state. By force of circumstance, if nothing else, something approaching religious freedom-a very crude model of the freedom we take for granted todayprevailed in England. Elizabeth preferred compromise to conflict, and it seems possible that she saw that the road to salvation for humanity did not lie in rigid ideological prescription, whether Roman or Protestant. We know that her protege Drake felt this way, for in religious discussion with one of his seamen he said that the man's parents, as Roman Catholics, would be saved, but that he urged his own Protestant Christianity as the way to go.

13