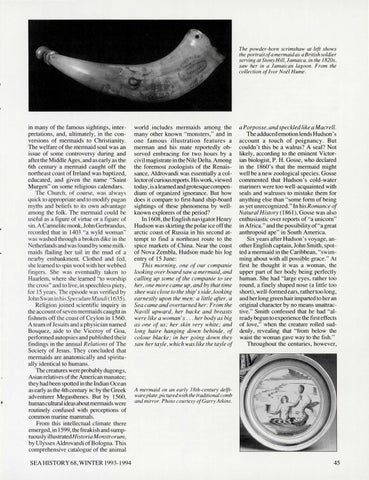

The powder-horn scrimshaw at left shows the portrait of a mermaid as a British soldier serving at Stony Hill , Jamaica, in the 1820s, saw her in a Jamaican lagoon. From the collection of Ivor Noel Hume.

in many of the famous sightings, interpretations, and, ultimately , in the conversions of mermaids to Christianity. The welfare of the mermaid soul was an issue of some controversy during and afterthe Middle Ages, and as early as the 6th century a mermaid caught off the northeast coast of Ireland was baptized, educated, and given the name " Saint Murgen" on some religious calendars. The Church, of course, was always quick to appropriate and to modify pagan myths and beliefs to its own advantage among the folk. The mermaid could be useful as a fi gure of virtue or a figure of sin. A Carmelite monk, John Gerbrandus, recorded that in 1403 "a wyld woman" was washed through a broken dike in the Netherlands and was found by some milkmaids fl ailing her tail in the mud of a nearby embankment. Clothed and fed, she learned to spin wool with her webbed fingers. She was eventually take n to Haarlem, where she learned "to worship the cross" and to live, in speechless piety, for 15 years. The episode was verified by John Swan in hisSpeculumMundi( l 635). Reli gion joined scientific inquiry in the account of seven mermaids caught in fi shnets off the coast of Ceylon in 1560. A team of Jesuits and a physician named Bosquez, aide to the Viceroy of Goa, performed autopsies and publi shed their findin gs in the annual Relations of The Society of Jesus. They concluded that mermaids are anatomically and spiritually identical to humans. The creatures were probably dugongs, Asian relatives of the American manatee; they had been spotted in the Indian Ocean as early as the 4th century ec by the Greek adventurer Megasthenes. But by 1560, human cultural ideas about mermaids were routinely confused with perceptions of common marine mammals. From thi s intellectual climate the re emerged, in 1599, the freaki sh and sumptuously illustrated H istoria M onstrorum , by Ulysses Aldrovandi of Bologna. Thi s comprehensive catalogue of the animal SEAHISTORY68,WINTER 1993- 1994

world includes mermaids among the many other known "monsters," and in one famous illu stration features a merman and his mate reportedly observed embracing for two hours by a civil magistrate in the Nile Delta. Among the foremost zoologists of the Renaissance, Aldrovandi was essentially a collectorof curious reports. His work, viewed today, is a learned and grotesque compendium of organized ignorance. But how does it compare to first-hand ship-board sightings of these phenomena by wellknown explorers of the period? In 1608, the English navigator Henry Hudson was skirting the polar ice off the arctic coast of Russia in his second attempt to find a northeast route to the spice markets of China. Near the coast of Nova Zembla, Hudson made his log entry of 15 June: This morning, one of our companie looking over board saw a mermaid, and calling up some of the companie to see her, one more came up , and by that time shee was close to the ship' s side, looking earnestly upon the men: a little after, a Sea came and overturned her: From the Na vill upward, her backe and breasts were like a woman's . .. her body as big as one of us; her skin very white; and long haire hanging down behinde, of colour blacke; in her going down they saw her tayle, which was like the tayle of

a P orposse, and speckled like a M acrell. The adduced emotion lends Hudson 's account a touch of poignancy. But couldn ' t this be a walrus? A seal? Not likely, according to the eminent Victorian biologist, P. H. Gosse, who declared in the l 860's that the mermaid might well be a new zoological species. Gosse commented that Hudson's cold-water mariners were too well-acquainted with seals and walruses to mistake them for anything else than "some form of being as yet unrecognized." In his Romance of Natural History (1861), Gosse was also enthusiastic over reports of "a unicorn" in Africa. " and the possibility of"a great anthropoid ape" in South America. Six years after Hudson ' s voyage, another Engli sh captain, John Smith, spotted a mermaid in the Caribbean, "swimming about with all possible grace." At first he thought it was a woman , the upper part of her body being perfectly human . She had " large eyes , rather too round , a finely shaped nose (a little too short), wel I-formed ears, rather too long, and her long green hair imparted to her an original character by no means unattractive." Smith confessed that he had "already begun to experience the first effects of love," when the creature rolled suddenly, revealing that "from below the waist the woman gave way to the fi sh." Throughout the centuries, however,

A mermaid on an early 18th-century delftware plate, pictured with the traditional comb and mirror. Photo courtesy of Garry Atkins.

45