(j

'

British lead became decisive. Iron shipbuilding, like the steam engine itself, derived from innovations of the 1700s. Engineer Captain Edgar Smith pointed out in his Short History of Naval and Marine Engineering in 1937: "It was the epoch-making discovery by Henry Cort in 1783, of the processes of producing wrought iron by puddling and of rolling it into plates and bars which provided the new race of engineers with the material for their boilers, their ships, their railways, and their bridges." That statement puts the development of the universal ocean steamship, capable of carrying cargo economicall y to the far comers of the world, in proper perspective. Ship development swam along in the mainstream of the Industrial Revolution, as part of the whole sweeping advance that was beginning to span England and America with rails and longspan bridges, and to power big machines to make cloth and paper and to replace hundreds of manual jobs from printing books to digging ditches.

Brunel's Great Iron Ship As usual in matters maritime, the conservati sm of the trade delayed progress toward the iron hull , and Brunel 's Great Britain of 1843 was the first really big iron ship to be built. But an iron hull was lighter and stronger than wood, and in the British Isles, where wood was in short suppl y, an iron hull was soon found to be about 20% cheaper per ton than a wooden one-per ton , that is, of what was already a markedl y more efficient ship. Brunel, with his penetrating insight into the possibilities of machine-age technology, embodied in this first great iron ship watertight bulkheads and a double bottom- innovations that made ships far safer in case of collision, hitting an iceberg, or stranding, the hazards responsibl e fo r most of the losses experienced at sea. Difficult as it is to grasp this today, before bulkheads and double bottoms were adopted, a ship was just one big tank inside. She needed only one sizeable hole in her outer skin to be assured of sinking. Right into the 20th-century, big sailing ships, even metal ones, were built with only a "collision bulkhead" say 20 feet abaft the stem. Hit them with anything substantial anywhere abaft that bulkhead, and they went down fast. The loss without trace of many fine, well-found ships undoubtedly stems from this fact. And of course, iron was more resistant than any kind of wood to the one great SEA HISTORY 64, WINTER 1992-93

hazard remauung, fire. The danger of simply being overwhelmed by a stormy sea, perhaps as a result of carrying canvas too long, or broaching to, or, in the case of a steamship, losing pumps and propulsion though flooded boiler rooms, has always ranked lower than the risk of collision, stranding or fire, simply because ships are designed to resist the sea and will generally do so successfull y, whether made of wood or iron, unless age has worn them out or something has happened to violate

their structural integrity. Leading up to Brunel's Great Britain were a succession of English canal boats made of iron, the first apparent! y as early as 1787, and then riverboats and, by the 1830s, sizable coasting steamers.

A New Order of Things Half a century after Fitch 's first trials, the Western World was agog with the steam engine. It appeared that a fundamental reordering of creation was going on in the mastery by mankind of un-

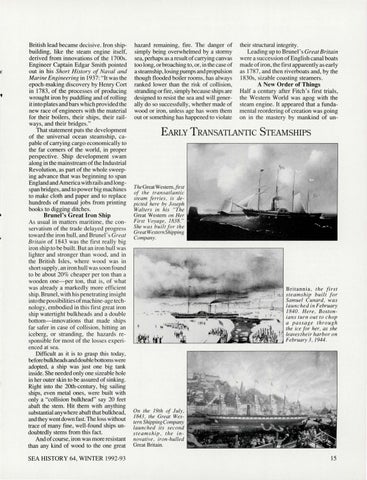

EARLY TRANSATLANTIC STEAMSHIPS

TheGreatWestem,first of the transatlantic steam ferries , is depicted here by Joseph Walters in his "The Great Western on Her First Voyage, 1838. " She was built fo r the Great Western Shipping Company.

Br itanni a, the f irs t steamship built fo r Samuel Cunard, wa s launched in Februmy 1840 . Here, Bostonians t urn out to chop a p assage thr oug h the ice fo r her, as she leaves their harb or on _,,,,.._.__...._.,.._..u.LIL.......I February 3, 1944.

On the 19th of July, 1843 , the Great Western Shipping Company launched its second steamship , the innovative, iron-hulled Great Britain.

15