COLUMBUS REDISCOVERED ago! So to Los Palos, in the late spring of 1492, he returned. The two caravels were Andalusian vessels, based on the Portuguese caravel design-lithe, speedy hulls designed to be driven by lateen rig. The Pinta had already been converted to square rig. Columbus converted the Nina (which turned out be his favorite ship) as soon as he got her to the Canary Islands , well to the south, off Africa, where he had planned from the beginning to make his westward departure. Critics have caught the point that square rig worked better than lateen running before the wind, in the Northeast Trades that begin a little south of the Canaries. Few have commented on the slashing dangers of a JOO-foot yard aloft, hanging a sail that can't be reefed and can't be tacked except by running off to raise the huge yard vertical and swing it round before the mast. Unquestionably it was this seamanly matter that led Columbus to insist on square rig for all his ships. The third ship he acquired was the nao (or "ship") Santa Maria, a robust representative of the European trader that had evolved from the marriage of the northern and southern streams of European ship development. Built in the northwestern province of Galicia and nicknamed La Gallega, she was capable of the outward voyage for sure. She was lost in the West Indies and so did not face the challenge of the stormy midwinter homeward passage. She carried about as much cargo as the other two ships combined. In keeping with the thinking of the age, she was made Columbus's flagship. How did these ships perform on the voyage? We'll have a look at that in our next issuse, when we tell the story of the voyage and what happened on the far shore. It is enough, perhaps, to say that European ship design had just reached the point where such a voyage could be made with safe return. The fabulous yams of 'Phoenicians, Romans and others being "blown across" the ocean, to which Morison objected so strongly, may yet tum out to be true. But the point was not just to make the crossing. It was to make it and come back. Here, perhaps, it is appropriate to remark that neither Phoenician craft, nor their Greek and Roman successors, were capable of that all-around ability to cope with brutal weather at sea that was needed to break into the ocean world-not from all we know of these vessels and how they were sai led. Viking ships, which enchant modem sailors with their elegant lines, were at risk whenever they put to sea and were absolutely unable to reach a contested point when the sea was up in arms. It is unlikely, within any reasonable limits of probability, that any Viking ship could have survived what Nina and Pinta went through in their return passage of 1493. Just What Sort of Ships Were These? The caravel sailed at the cutting edge of the voyages of exploration that opened the ocean world. And Jose Maria Martinez-Hidalgo, former director of the Maritime Museum of Barcelona, recognized by the late Howard I. Chapelle as the leading authority on Columbus's ships, has pointed out a special quality of the Andalusian caravels that sailed from Los Palos. From an early date they were converted from lateen rig to square rig on the fore and main (the two principal masts), leaving only the small mizzen (and sometimes a diminutive fourth mast, or bonaventure mizzen) lateen-rigged. The Portuguese, who pioneered this offshore deepwater sailing, at first converted only the foremast to square rig, leaving the main and mizzen lateen. The Andalusians, borrowing from and improving upon the Portuguese experience, rigged two masts square. Ultimately the Andalusian model prevailed, and SEA HISTORY 54, SC' ¡rviER 1990

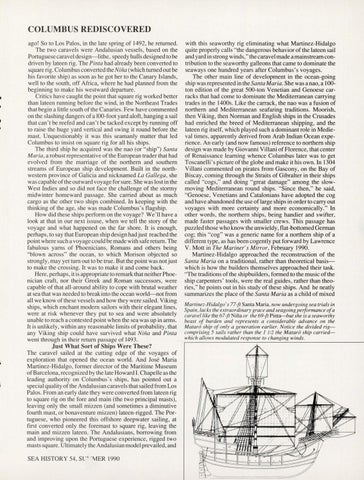

with thi s seaworthy rig eliminating what Martinez-Hidalgo quite properly calls "the dangerous behavior of the lateen sail and yard in strong winds," the caravel made a mainstream contribution to the seaworthy galleons that came to dominate the seaways one hundred years after Columbus's voyages. The other main line of development in the ocean-going ship was represented in the Santa Maria. She was anao, a 100ton edition of the great 500-ton Venetian and Genoese carracks that had come to dominate the Mediterranean carrying trades in the 1400s. Like the carrack, the nao was a fusion of northern and Mediterranean seafaring traditions. Moorish, then Viking, then Norman and English ships in the Crusades had enriched the breed of Mediterranean shipping, and the lateen rig itself, which played such a dominant role in Medieval times, apparently derived from Arab Indian Ocean experience. An early (and now famo us) reference to northern ship design was made by Giovanni Villani of Florence, that center of Renaissance learning whence Columbus later was to get Toscanelli's picture of the globe and make it hi s own. In 1304 Villani commented on pirates from Gascony, on the Bay of Biscay, coming through the Straits of Gibralter in their ships called "cogs," and doing "great damage" among the slowmoving Mediterranean round ships. "Since then," he said, "Genoese, Venetians and Catalonians have adopted the cog and have abandoned the use oflarge ships in order to carry out voyages with more certainty and more economically." In other words, the northern ships, being handier and swifter, made faster passages with smaller crews. This passage has puzzled those who know the unwieldy, flat-bottomed German cog; this "cog" was a generic name for a northern ship of a different type, as has been cogently put forward by Lawrence V. Mott in The Mariner's Mirror , February 1990. Martinez-Hidalgo approached the reconstruction of the Santa Maria on a traditional, rather than theoretical basiswhich is how the builders themselves approached their task. "The traditions of the shipbuilders, formed to the music of the ship carpenters' tools, were the real guides, rather than theories," he points out in his study of these ships. And he neatly summarizes the place of the Santa Maria as a child of mixed Martinez-Hidalgo' s 77-ft Santa Maria, now undergoing sea trials in Spain , lacks the extraordinary grace and seagoing performance of a caravel like the 67-ft Nifia or the 69-ft Pinta--but she is a seaworthy beast of burden and represents a considerable advance on the Matar6 ship of only a generation earlier. Notice the divided ril(comprising 5 sails rather than the 1 112 the Matar6 ship carried-which allows modulated response to changing winds.