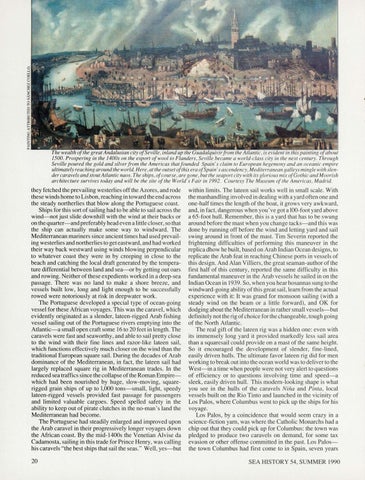

The wealth of the great Andalusian city of Seville, inland up the Guadalquivir from the Atlantic, is evident in this painting of about 1500. Prospering in the 1400s on the export of wool to Flanders, Seville became a world-class city in the next century. Through Seville poured the gold and silver from the Americas that founded Spain's claim to European hegemony and an oceanic empire ultimately reaching around the world. Here , at the outset ofthis era ofSpain's ascendency, Mediterranean galleys mingle with slender cara vels and stout Atlantic naos. The ships, of course, are gone, hut the seaport city with its glorious mix ofGothic and Moorish architecture survives today and will he the site of the World's Fair in 1992. Courtesy The Museum of the Americas, Madrid.

they fetched the prevai ling westerlies off the Azores, and rode these winds home to Lisbon, reaching in toward the end across the steady northerlies that blow along the Portuguese coast. Ships for this sort of sai ling had to be able to sail across the wind-not just slide downhill with the wind at their backs or on the quarter-and preferably head even a little closer, so that the ship can actually make some way to windward. The Mediterranean mariners since ancient times had used prevailing westerlies and northerlies to get eastward, and had worked their way back westward using winds blowing perpendicular to whatever coast they were in by creeping in close to the beach and catching the local draft generated by the temperature differential between land and sea--or by getting out oars and rowing. Neither of these expedients worked in a deep-sea passage. There was no land to make a shore breeze, and vessels built low, long and light enough to be successfully rowed were notoriously at risk in deepwater work. The Portuguese developed a special type of ocean-going vessel for these African voyages. This was the caravel, which evidently originated as a slender, lateen-rigged Arab fishing vessel sailing out of the Portuguese rivers emptying into the Atlantic-a small open craft some 16 to 20 feet in length. The caravels were fast and seaworthy, and able to sail pretty close to the wind with their fine lines and razor-like lateen sail, which functions effectively much closer on the wind than the traditional European square sail. During the decades of Arab dominance of the Mediterranean, in fact, the lateen sail had largely replaced square rig in Mediterranean trades. In the reduced sea traffics since the collapse of the Roman Empirewhich had been nourished by huge, slow-moving, squarerigged grain ships of up to 1,000 tons-small, light, speedy lateen-rigged vessels provided fast passage for passengers and limited valuable cargoes. Speed spelled safety in the ability to keep out of pirate clutches in the no-man's land the Mediterranean had become. The Portuguese had steadily enlarged and improved upon the Arab caravel in their progressively longer voyages down the African coast. By the mid-1400s the Venetian Alvise da Cadamosta, sailing in this trade for Prince Henry, was calling his caravels " the best ships that sail the seas." Well, yes-but 20

within limits. The lateen sail works well in small scale. With the manhandling involved in dealing with a yard often one and one-half times the length of the boat, it grows very awkward, and, in fact, dangerous when you've got a 100-foot yard above a 65-foot hull. Remember, this is a yard that has to be swung around before the mast when you change tacks-and this was done by running off before the wind and letting yard and sail swing around in front of the mast. Tim Severin reported the frightening difficulties of performing this maneuver in the replica dhow he built, based on Arab Indian Ocean designs, to replicate the Arab feat in reaching Chinese ports in vessels of this design. And Alan Villiers, the great seaman-author of the first half of this century, reported the same difficulty in this fundamental maneuver in the Arab vessels he sailed in on the Indian Ocean in 1939. So, when you hear hosannas sung to the windward-going ability of this great sail, learn from the actual experience with it: It was grand for monsoon sailing (with a steady wind on the beam or a little forward), and OK for dodging about the Mediterranean in rather small vessels-but definitely not the rig of choice for the changeable, tough going of the North Atlantic. The real gift of the lateen rig was a hidden one: even with its immensely long yard it provided markedly less sail area than a squaresail could provide on a mast of the same height. So it encouraged the development of slender, fine-lined, easily driven hulls. The ultimate favor lateen rig did for men working to break out into the ocean world was todeliverto the West-in a time when people were not very alert to questions of efficiency or to questions involving time and speed-a sleek, easily driven hull. This modem-looking shape is what you see in the hulls of the caravels Nina and Pinta, local vessels built on the Rio Tinto and launched in the vicinity of Los Palos, where Columbus went to pick up the ships for his voyage. Los Palos, by a coincidence that would seem crazy in a science-fiction yam, was where the Catholic Monarchs had a chip out that they could pick up for Columbus: the town was pledged to produce two caravels on demand, for some tax evasion or other offense committed in the past. Los Palosthe town Columbus had first come to in Spain, seven years SEA HISTORY 54, SUMMER 1990