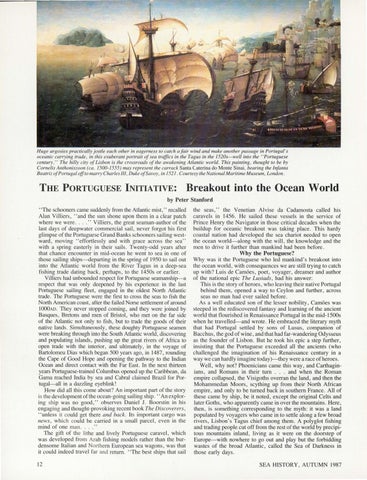

Huge argosies practically jostle each other in eagerness to catch a fair wind and make another passage in Portugal's oceanic carrying trade, in this exuberant portrait of sea traffics in the Tagus in the 1520s-well into the "Portuguese century." The hilly city of Lisbon is the crossroads of the awakening Atlantic world. This painting, thought to be by Corne/is Anthoniszoon (ca . 1500-1555) may represent the carrack Santa Caterina do Monte Sinai, bearing the lnfanta Beatriz ofPortugal off to marry Charles Ill, Duke ofSavoy , in 1521. Courtesy the National Maritime Museum, London.

THE PORTUGUESE INITIATIVE:

Breakout into the Ocean World

by Peter Stanford ' 'The schooners came suddenly from the Atlantic mist,'' recalled Alan Villiers , "and the sun shone upon them in a clear patch where we were .... '' Villiers, the great seaman-author of the last days of deepwater commercial sail, never forgot his first glimpse of the Portuguese Grand Banks schooners sailing westward , moving " effortlessly and with grace across the sea" with a spring easterly in their sails. Twenty-odd years after that chance encounter in mid-ocean he went to sea in one of thqse sailing ships-departing in the spring of 1950 to sail out into the Atlantic world from the River Tagus in a deep-sea fishing trade dating back , perhaps , to the 1450s or earlier. Villiers had unbounded respect for Portuguese seamanship--a respect that was only deepened by his experience in the last Portuguese sailing fleet, engaged in the oldest North Atlantic trade. The Portuguese were the first to cross the seas to fish the North American coast, after the failed Norse settlement of around IOOOAD. They never stopped coming , and they were joined by Basques, Bretons and men of Bristol, who met on the far side of the Atlantic not only to fi sh, but to trade the goods of their native lands. Simultaneously, these doughty Portuguese seamen were breaking through into the South Atlantic world, discovering and populating islands, pushing up the great rivers of Africa to open trade with the interior, and ultimately, in the voyage of Bartolomeu Dias which began 500 years ago, in 1487, rounding the Cape of Good Hope and opening the pathway to the Indian Ocean and direct contact with the Far East. In the next thirteen years Portuguese-trained Columbus opened up the Caribbean , da Gama reached India by sea and Cabral claimed Brazil for Portugal-all in a dazzling eyeblink! How did all this come about? An important part of the story is the development of the ocean-going sailing ship . ' ' An exploring ship was no good," observes Daniel J . Boorstin in his engaging and thought-provoking recent book The Discoverers , "unless it could get there and back. Its i"mportant cargo was news , which could be carried in a small parcel, even in the mind of one man . ... " The gift of the lithe and lively Portuguese caravel, which was developed fro m Arab fishing models rather than the burdensome Italian and Northern European sea wagons , was that it could indeed travel far and return. " The best ships that sail 12

the seas," the Venetian Alvise da Cadamosta called his caravels in 1456 . He sailed these vessels in the service of Prince Henry the Navigator in those critical decades when the buildup for oceanic breakout was taking place. This hardy coastal nation had developed the sea chariot needed to open the ocean world-along with the will, the knowledge and the men to drive it further than mankind had been before.

Why the Portuguese? Why was it the Portuguese who led mankind's breakout into the ocean world , with consequences we are still trying to catch up with ? Luis de Cam6es, poet , voyager, dreamer and author of the national epic The Lusiads, had his answer: This is the story of heroes , who leaving their native Portugal behind them, opened a way to Ceylon and further , across seas no man had ever sailed before . As a well educated son of the lesser nobility, Camoes was steeped in the rediscovered fantasy and learning of the ancient world that flourished in Renaissance Portugal in the mid- I 500s when he travelled-and wrote . He embraced the literary myth that had Portugal settled by sons of Lusus, companion of Bacchus, the god of wine, and that had far-wandering Odysseus as the founder of Lisbon. But he took his epic a step further, insisting that the Portuguese exceeded all the ancients (who challenged the imagination of his Renaissance century in a way we can hardly imagine today)-they were a race of heroes . Well , why not? Phoenicians came this way, and Carthaginians, and Romans in their turn . . . and when the Roman empire collapsed, the Visigoths overran the land, and then the Mohammedan Moors, scything up from their North African empire, and only to be turned back in southern France. All of these came by ship, be it noted, except the original Celts and later Goths, who apparently came in over the mountains. Here, then, is something corresponding to the myth: it was a land populated by voyagers who came in to settle along a few broad rivers , Lisbon ' s Tagus chief among them. A polyglot fishing and trading people cut off from the rest of the world by precipitous mountains inland, living as it were on the doorstep of Europe-with nowhere to go out and play but the forbidding wastes of the broad Atlantic, called the Sea of Darkness in those early days. SEA HISTORY, AUTUMN 1987