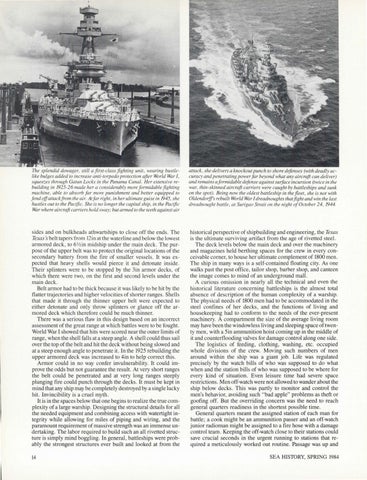

The splendid dowager, still a first-class fighting unit, wearing bustlelike bulges added to increase anti-torpedo protection after World War I, squeezes through Gatun Locks in the Panama Canal. Her extensive rebuilding in 1925-26 made her a considerably more f ormidable fighting machine, able to absorb far more punishment and better equipped to f end off attack from the air. Al far right, in her ultimate guise in 1945, she hustles out to the Pacifi c. She is no longer the capital ship, in the Pacific War where aircraft carriers hold sway; but armed to th e teeth against air

attack, she delivers a knockout punch to shore def enses (with deadly accuracy and penetrating power far beyond what any aircraft can deliver) and remains a formidabl e def ense against surface incursion (twice in rhe war, thin-skinned aircraft carriers were caught by battleships and sunk on the spot). Being now the oldest battleship in the fleet , she is not with Oldendorffs rebuilt World War I dreadnoughts that fight and win the last dreadnought battle, at Surigao Strait on the night of October 24, 1944.

sides and on bulkheads athwartships to close off the ends. The Tex.as s belt tapers from 12in at the waterline and below the lowest armored deck , to 6'h in midship under the main deck . The purpose of the upper belt was to protect the original locations of the secondary battery from the fire of smaller vessels. It was expected that heavy shells would pierce it and detonate inside. Their splinters were to be stopped by the 3in armor decks, of which there were two, on the first and second levels under the main deck . Belt armor had to be thick because it was likely to be hit by the flatter trajectories and higher velocities of shorter ranges . Shells that made it through the thinner upper belt were expected to either detonate and only throw splinters or glance off the armored deck which therefore could be much thinner. There was a serious flaw in this design based on an incorrect assessment of the great range at which battles were to be fought . World War I showed that hits were scored near the outer limits of range, when the shell fall s at a steep angle. A shell could thus sail over the top of the belt and hit the deck without being slowed and at a steep enough angle to penetrate it. In the 1925 rebuilding the upper armored deck was increased to 4in to help correct this. Armor could in no way confer invulnerability. It could improve the odds but not guarantee the result. At very short ranges the belt could be penetrated and at very long ranges steeply plunging fire could punch through the decks. It must be kept in mind that any ship may be completely destroyed by a single lucky hit. Invincibility is a cruel myth. It is in the spaces below that one begins to realize the true complexity of a large warship. Designing the structural details for all the needed equipment and combining access with watertight integrity while allowing for miles of piping and wiring, and the paramount requirement of massive strength was an immense undertaking. The labor required to build such an all rivetted structure is simply mind boggling. In general, battleships were probably the strongest structures ever built and looked at from the

historical perspective of shipbuilding and engineering, the Texas is the ultimate surviving artifact from the age of rivetted steel. The deck levels below the main deck and over the machinery and magazines held berthing spaces for the crew in every conceivable corner, to house her ultimate complement of 1800 men . The ship in many ways is a self-contained floating city. As one walks past the post office, tailor shop, barber shop, and canteen the image comes to mind of an underground mall . A curious omission in nearly all the technical and even the historical literature concerning battleships is the almost total absence of description of the human complexity of a warship. The physical needs of 1800 men had to be accommodated in the steel confines of her decks, and the functions of living and housekeeping had to conform to the needs of the ever-present machinery. A compartment the size of the average living room may have been the windowless living and sleeping space of twenty men , with a Sin ammunition hoist coming up in the middle of it and counterflooding valves for damage control along one side. The logistics of feeding , clothing, washing, etc. occupied whole divisions of the crew. Moving such numbers of men around within the ship was a giant job. Life was regulated precisely by the watch bills of who was supposed to do what when and the station bills of who was supposed to be where for every kind of situation. Even leisure time had severe space restrictions. Men off-watch were not allowed to wander about the ship below decks . This was partly to monitor and control the men's behavior, avoiding such "bad apple" problems as theft or goofing off. But the overriding concern was the need to reach general quarters readiness in the shortest possible time. General quarters meant the assigned station of each man for battle; a cook might be an ammunition passer and an off-watch junior radioman might be assigned to a fire hose with a damage control team . Keeping the off-watch close to their stations could save crucial seconds in the urgent running to stations that required a meticulously worked out routine. Passage was up and

14

SEA HISTORY, SPRING 1984