3 minute read

Torrey Pines reservea rare gemthatneedsalittlepolish

On a map ofSouthernCaliforniathere is a tiny speckof wilderness wild coastsurrounded by a seaof urban rooftops.

Atlessthan2,000acresinsize, TorreyPinesState NaturalReserve is a smalltreasure inCalifornia’s wildlandscapeaspart of thestate park system.

Advertisement

Butit’s technicallynot a state park.

While TorreyPinesincludesa popularstate recreationbeach, theheart ofthe reservewas set asidefortheprotection ofits namesake pinetrees onlyfound here andonSantaRosaIslands off the California coast.Thetrees were first recognizedas a new speciesin 1850.

Theuniquehabitatwithin the reserve alsohostsseveralrare and endangeredplants, a lagoon, and nestingplacesforseveraluncommonbird species.

The reserve differs from a state park becausetheprimary mission ispreservationofhabitat and the tiny grove ofrare trees.There are over 300 units in California’s state park system,but only 16 are classifiedas reserves. Unlike other pinesthatstand tall andstraight,the Torreypine canberandomlyshaped, twisted and convolutedasit grows toa height of nearly 50 feet.

Visitors to TorreyPinescan enjoymiles of hiking trails,but there are no campgrounds or picnicfacilities,andpetsare not allowedanywhere in the reserve. With the reserve’s smallfootprint andits collectionofunique species,such activitiesare simply not compatible. Thatmakes TorreyPinesa hiker’s paradisewhere one can wander on miles oftrailsand enjoy a stunninghabitatthathas not changedsignificantlysince the Kumeyaaycalledthese coastalpine groveshome. The deeplyerodedsandstone landscapeisdotted withthe tortured pinetrees, a collectionof wildcreatures,unseeninurban areas and breathtaking vistas of earth,skyand ocean.Attheright time, visitorslookingseaward mayspotthespoutingof a surfacingwhale, or evena rising fluke as they turn to dive.

Theearth’s history is on displayhere, as theinterfacebetween landandseahas cut awaysandstonecliffs that tell a story of creation goingback 50 million years.Onthesecliffs,nesting falconsdelightbirders every spring as eggs hatch and chicks learn to fly andhunt.

Despite thebestefforts ofstate park rangers,park staffand dedicated volunteers, TorreyPines Reserve is beingloved to death.

Withnearly 3 millionannual visitors,limitedstate budgets and increased visitor demand, this rare gem is a bit tarnishedand needs a littlepolish.

That’s what RickGulleyhopes to do.

Gulley will becomepresident of the TorreyPinesConservancy later thismonthandisbringing lots ofideasandenthusiasm to hisnew job. Gulley replacesPeter Jensen whohas served forthe pastnine years. The conservancyis a groupof supportersthatprimarily raise funds and engage inadvocacyfor the reserve It works closelywith the TorreyPinesDocentSociety whose volunteersstaff thevisitor center, conductinterpretative and children’s programs,andassist with trail work.

Gulley comes with a deephistory ofsupportingthe environment havingserved on the boardsoftheAnzaBorrego Foundation, SanDiego Zoo Global ScrippsInstitutionof Oceanography, NationalRecreation and Park Association, and as a memberoftheSanDiego City Parks and RecreationBoard. Thisformerinsurance executive doesn’tthinksmall.

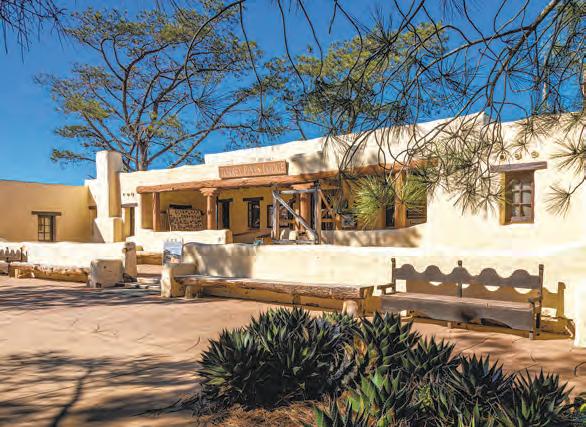

Asthenew leader of the conservancy, he comeswith a goal of restoring the adobe visitorcenter, alsoknownasTheLodge, thatwill mark its 100th anniversary next February.

Thishistoric adobe was built as a restaurantin 1923 byEllen BrowningScripps, a historical iconofSanDiego.Recognizing theneed to protectthese rare pine trees,Scrippspurchased two parcelsoflandforpreservationin

1909and 1912 Bythattime,neglectandindifferencehad reducedthe Torreypinenumbers to only a few hundred Today there are over 3,000trees, thanks to protection planting and restorationefforts.

Good fortune,foresightand fortitudecame together to create TorreyPinesReserve.

Asearly as 1888it was suggested thatthepinesbeprotected, but it was notuntil 10 yearslaterthatSanDiego created TorreyPinesPark. By 1921, thepines were being destroyedby firewood collectors andthisled to creation ofthe reserve thatincluded the Scripps parcels Inthe 1950s, the beach andupland reservewere transferred to thestate.

Over the years,theadobe lodge hasdeteriorated.Design plansfor restorationare complete, but anestimated$3 to $4 millionisneededfor the work and that’s whatGulleyhopes to find.

Hehas other grandvisions thathesharedas we meandered throughthepines,includinga new rangerheadquartersand observationbuilding better restroomfacilities,landscaping, and programs “thatwillmake sure thisplaceishere forfuture generations.”

Scripps.

“I want to make certain an uncertainfuture for TorreyPines,” Gulley said.

Gulleyhas a deep respect for theScrippslegacy, alongwitha profoundlove of nature Torrey Pinesoffershim a nearbyplace where hehikes weekly and can enjoytheplantsandanimals where ocean and land collide.

Summershere can be hot,but there canbefoggy spring days, strong winter storms,blooming spring wildflowers,andthe excitementofmigratingbirds.

Gulleyknows thatmostof the visitors to TorreyPinesare local, buthe wouldlike to see thatfootprint expanded.

“We know thatmanyarea residentshave never beenhere.I’d like to make them feel welcome,” hesaid.

IwishGulley greatsuccess.As wildplacesbecomeharder to find, ajewel like TorreyPinesbecomes even more necessary to future generations. Emailernie@packtrain.comorvisit erniesoutdoors.blogspot.com.

PHOTOGRAPHERANDLAJOLLASECOND-GRADERS COLLABORATEON BOOK

you’re safenow.’”

Mosssaid.

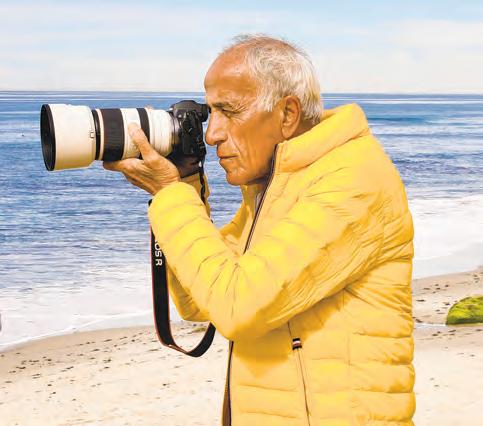

LAJOLLA Anew projecthastaken flightamonglocalphotographerEssyGhavameddini andstudentsatStella

MarisAcademyin La Jolla.

Overthepastfew months,Ghavameddiniand the childrenhavecomposed abookcalled“Welcome Baby Hummingbirds,”a collectionofGhavameddini’s photographs ofa hummingbird anditsbabies with text written bythe students.

The conceptforthebook was laid when Ghavameddinivisited friendsin Rancho Santa Fe Their2-yearolddaughter was enamored of a hummingbird andits nest justoutside their front door andshowed Ghavameddini.

Ghavameddini, who once owned a photography gallery in La Jolla’s Village andhas 30years’ experience as theofficialphotographerfor SanDiego’s sportsarena and several more years shootingnational sporting events, decided to photograph the hummingbird andher babies every other day over 28 days.

Ashisidea to compile thephotosintoa book grew, Ghavameddinifeltit would be bestif the words were written by children.

He approachedStella MarisAcademyPrincipal Francie Mossforhelp.

Moss asked her staffif anyone was interestedin taking ontheproject and saidsecond-grade teacher MichelleCampagna volunteered,anarrangement that alignedwithherclass’s curriculum on animal habitats.

Thebook “really fit in beautifully withthestudents studies, Mosssaid.

ShesaidCampagna thendisplayedeach of

Ghavameddini’s photos andaskedher 17 students to write text for them. Thestudents then voted ontheirfavorite text for each page, and Campagna ensuredeach studenthad one page inthebook.

The text, Moss said, serves ascaptionsforthe photos“butit’s in children’s language, taking on the personaofthehummingbird (such as)‘Oh,thebaby birdsare hungry Feedme, Mommy ...Daddy’s home;