4 minute read

Typewriters, pencils and notebooks

By John Gierach Redstone Review

Advertisement

LYONS – I think it was sometime in the early 2000s that I heard an interview on NPR with an elderly editor at The New Yorker magazine whose name I don’t remember. After a few innocuous questions, it became obvious that this man was considered interesting not because of his many accomplishments, but because he still did his writing on a manual typewriter and his editing on paper with a red pencil.

The young interviewer was polite, but clearly saw this guy as a woolly mammoth who’d been frozen in the ice and only recently thawed out as a kind of living artifact. Finally, he got around to the question he’d been wanting to ask from the beginning: “Why don’t you get a computer?” The editor said, “Because computers don’t speak to my circumstances.”

People who’ve worked with language all their lives have an enviable knack for the conversation-ending – or in this case interview-ending – comment.

I started out the same way: with a manual typewriter, paper and pencils. For interviews I had a big black phone with a shoulder cradle on the receiver that left both my hands free to hold a tablet and scribble notes. Then I’d have to immediately transcribe those notes on the typewriter while I could still read my own writing. They’d tried to teach me penmanship in elementary school, but like so many other things, it didn’t take.

By the time I heard that interview I’d already mothballed the typewriter and was using a computer. I’d been working more or less steadily as a freelance writer for about fifteen years by then, typing no fewer than three drafts per story. In draft number one I’d get a thing or two right and begin to see a glimmer of hope; in draft number two I’d get a few more things right and settle on a structure that would work for the material and by draft number three I’d usually have it nailed.

But even that third draft was marred by typos, strike-outs and penciled corrections,

There was an annoying learning curve, but at first the promise panned out. I could spend more time actually writing and less in what had begun to seem like pointless, repetitive drudgery. And my use – that is waste – of paper went down by three quarters. I don’t know that I put out more work because there’s more involved in a good story than just the time it takes to type it, but what I did put out came easier.

But there were things I hadn’t foreseen, like upgrades. I stuck with my first writing program – a cumbersome old thing called Wordstar – for longer than I should have simply because I knew how to use it, but I enough that, although they were familiar, things weren’t where I expected them to be. I once naïvely thought that operating a computer would be like driving a car: once I learned I’d be able to drive anything short of an 18-wheeler or a tank. And that’s sort of true with computers, except that when I sit down at a new one I find that the brake pedal is now where the radio used to be, the gear shift is on the ceiling and I have to call someone to find out where the ignition is. so I’d have to laboriously retype the final draft neatly so it could be mailed to an editor. That’s a lot of typing when you do it with two fingers. It was one thing with an 800-word newspaper column, something else with a 2,500-word magazine story and a whole new world of hurt with an 80,000word book. remember the day it went sour on me. The head computer guy at my publisher called and said “We’re having trouble reading your manuscript.” I said “Let me get this straight: you’re the computer guy at Simon & Schuster and you’re calling a writer in Colorado for advice?”

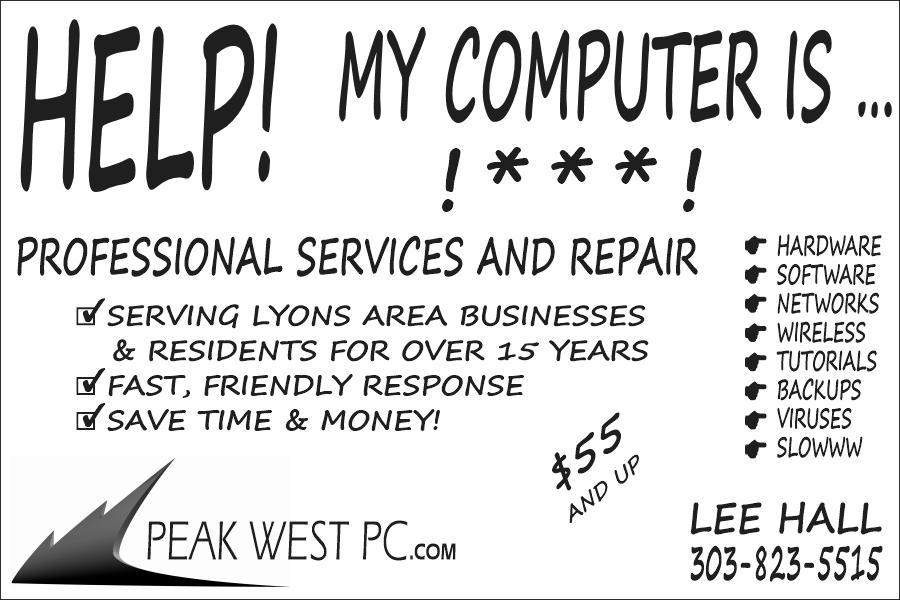

The person I call is Lee Hall, our local computer guru. I suspect that he rolls his eyes every time he hears my voice on his answering machine, but he’s always patient with me and there’s never been a time when he didn’t get the job done. The last time I called was when I recently got a new printer. The old one printed its last page after 27 years of service (no complaints there) and when I got the new one home from the store, I sat down with the handy eight-step Quick Setup Guide and waded in. Predictably, I stalled on step four when my computer informed me that it “didn’t recognize the device,” which I didn’t consider to be my problem.

Computers weren’t ubiquitous yet and I was leery of them – I’d seen too many science fiction movies in which computers went insane and exploded – but too many writer friends touted the luxury of doing all the editing, cutting, pasting and deleting on the screen and then relaxing with a cup of coffee while the printer typed the final manuscript.

He said, “I take your point, we’ll work it out,” and hung up, but the writing was on the wall. It was time to join the 21st Century, like it or not.

I’m not sure how many computers I’ve gone through since then – I’m guessing five, but it might have been six – and each one sent me back into another time-consuming learning curve. Even newer versions of familiar programs changed just

So I called Lee and he got it hooked up, although it took him an hour and there was some muttering and head-scratching. All told – and not counting a few deadend alleys – it took many, many more than eight steps. Quick setup my ass.

Anyway, that’s when I remembered that interview with that New Yorker editor and caught myself envying him. But for better or worse, computers do speak to my circumstances, it’s just that it was computers themselves that changed those circumstances while all but a handful of the rest of us followed along as blindly as lemmings. The next time I talk to Lee, I’ll have to ask him how that happened.