6 minute read

Spikin up fur Scots

by Paul Kelbie

Every January millions of people across the globe celebrate the birth of Robert Burns, an Ayrshire farmer who wrote some of the world’s most famous poetry and songs in a language unique to Scotland.

Advertisement

Burns wrote as he spoke in the 18th century and he has been lauded for it for more than 220 years. However, modern day proponents of the same language are often harangued, ridiculed and attacked by those fearful of the power of a ‘guid Scots tongue’.

Fife poet Len Pennie and Aberdeenshire singer Iona Fyfe are leading lights of a new generation of proud Scots speakers. They have received accolades and gathered thousands of followers from around the world who enjoy what they do.

Although still only 21-years-old Len has attracted attention from as far away as Australia after posting a poem called ‘I’m No Havin’ Children’ and a series of ‘Scots Word of the Day’ videos on social media. She is now one of the country’s most high-profile campaigners for a language spoken by more than 1.5million people.

Directions to the toilets in English, Gaelic and Scots

Photo by Kenneth Allen CC BY-SA 2.0

Award winning singer Iona, 22, is in increasing demand for performances around the world. Had it not been for the Covid pandemic and international travel restrictions last year should have been her busiest yet, with tours scheduled for the US and Australia among others.

An enthusiastic champion of her mother tongue she recently succeeded in encouraging the digital music streaming service Spotify to include Scots in the list of languages that songs can be categorised in. The music giant issued a public apology and promised a resolution.

However, despite their popularity, both women have had to endure a campaign of personal abuse from social media trolls - mostly anonymous angry men - who appear threatened by the growing

“Some of the personal attacks about my appearance and other things have been horrendous. I’ve been accused of being ignorant, uneducated and unable to speak properly,” said Iona, who graduated from university with two degrees and was a finalist in the prestigious BBC Radio Scotland Young Traditional Musician of the Year 2021.

“If some of the abuse I’ve received was directed at speakers of Gaelic or other languages that have more protection it would be classed as a hate crime.

“Scots speakers are not taken seriously unless they adopt a more neutral dialect and speak in a sort of ‘radio voice’. They’ve been encouraged to self censor how they speak.”

It’s not so long ago since children could be belted at school for speaking Scots

The ‘cultural cringe’ experienced by many Scots speakers is something sociology graduate and writer Colin Burnett can readily identify with.

“I was in a shop recently and there was a wee girl with her mother who asked for some breed. She was immediately corrected to say bread and told off for talking like that outside the home,” said Colin, 31, whose short stories in Scots have found favour with an increasingly curious audience - especially in the US, Canada and Australia - looking to connect with their roots.

“For the last thee centuries, until quite recently, there has been a deliberate attempt to suppress our true voice. I certainly wasn’t encouraged to speak Scots at school. I have friends who won’t read my work now because it is written the way they speak - in Scots. There is a stigma that if it’s in Scots it is somehow less important or inferior to English.

“In 1993 a teenager was detained in a prison cell and threatened with contempt for answering ‘Aye’ instead of ‘Yes’ to a question in Stirling Sheriff Court. That is ridiculous!”

Scots was an accepted language long before the union of parliaments in 1707. It was used in legal papers and official documents. It was the language of kings, lawyers, scholars and poets.

“Robert Burns exemplifies the power of Scots. He took the language of his local environment in Ayrshire and made it global. His words still send ripples across continents and break down cultural barriers. You don’t see people in Russia, America or Japan refusing to read his work because it’s written in Scots but you will find people in Scotland like that,” said Colin.

Susi Briggs and Alan McClure started Oor Wee Podcast for children

The Edinburgh-based writer is just one of a growing number of voices calling for Scots to be encouraged and taught in schools to encourage future generations to embrace rather than deny their cultural identity.

Author, storyteller, musician and songwriter Susi Briggs from Dumfries and Galloway has recently launched a new podcast with Alan McClure from Aberdeen that is aimed at children.

“Oor wee Podcast is full of stories and songs in a language they maybe speak themselves or hear spoken at home,” said Susi, who admits having to fight against the ‘cringe factor’ throughout her career and deal with her own share of abuse online.

“I got pelters on Twitter after one of my stories written in Scots for children appeared on BBC Scotland. The sheer lack of awareness about the language, particularly among Scots, is breathtaking. They’ve been told it’s a dialect or slang but to call it that takes away its importance and our sense of identity.

“We have to inspire the younger generation to enjoy it and understand it is as beautiful as any other language on this planet. A lot of primary school children, their families and teachers enjoy my work, and I’ve got a following in America where there’s a lot of interest,” said Susi.

Her Scots writing career really took off about eight years ago after a publisher turned down her story, ‘The Wee Sleepy Sheepy’, because it had too much of a “Scottish flavour to it”. Instead of removing the word “wee” she rewrote it completely in Scots to much acclaim.

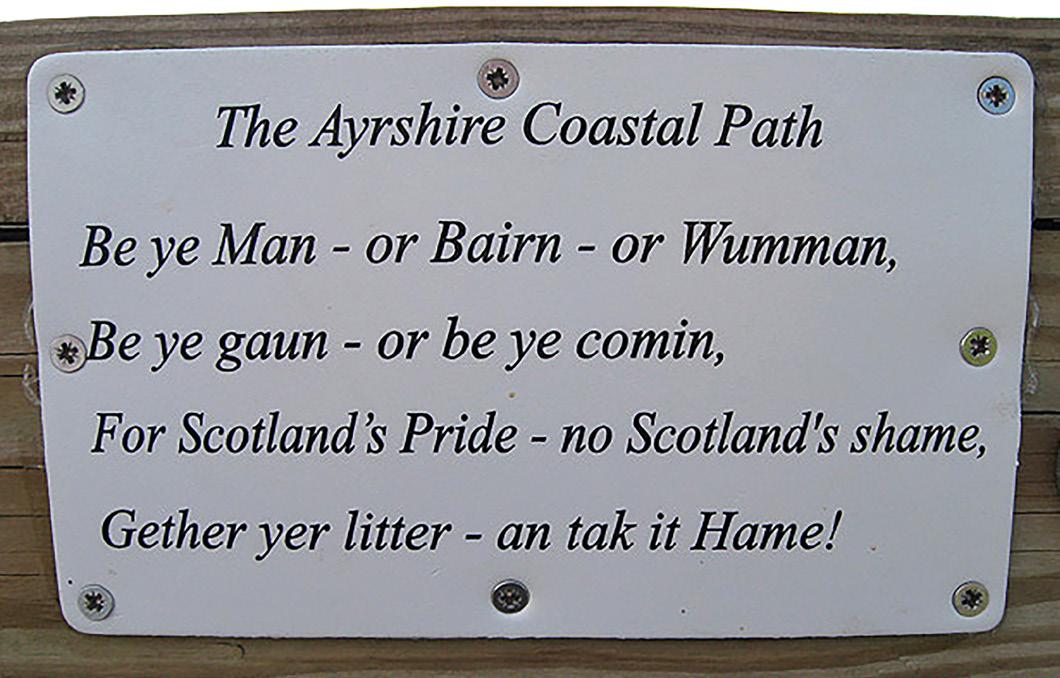

A sign on the Ayrshire Coastal Path

Photo by Walter Baxter CC BY-SA 2.0.

According to the last official census some 1,541,693 people speak Scots and anyone who claims it is only a dialect of English or slang is wrong.

Scots is acknowledged as an official language by the Ethnologue (https://www. ethnologue.com/), a compendium of all 7,117 known living languages in the world. It is also recognised by the European Union’s Regional and Minorities Language Charter of which the UK Government is a signatory.

“Scots has all the necessary ingredients to be called a language. It is different enough from English to be unintelligible to someone who has not been taught it,” said Dr Joanna Kopaczyk, Senior Lecturer in Scots and English at the University of Glasgow.

“The problem is people have been led to believe the only variant in the British isles that can be given the label of language is standard English.

“I’m Polish but I’ve been researching the history of the Scots language for about 20 years. I find it particularly puzzling, and a bit sad, that in Scotland the history of Scots is unknown.”

Sign in Glen Tanar

Photo by Alan Findlay CC BY-SA 2.0

However, times and attitudes are changing. A new research project, ‘The Future of Scots’, aims to lay the groundwork for community driven language policy making and new areas of academic research.

It is a collaborative research project, spearheaded by the University of Glasgow, in concert with Education Scotland and the campaign group Oor Vyce, supported by The Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Members of the public are encouraged to get involved and help by taking part in a short online survey which can be found at https://scotslanguagepolicy. glasgow.ac.uk/en/welcome/