LEXINGTON ROAD

THE WHOLE COUNSEL OF GOD

TR. ALBERT MOHLER, JR.

TR. ALBERT MOHLER, JR.

he recovery of biblical theology has been one of the hallmark milestones of evangelical Christians over the course of the last several decades. Biblical theology, understood as a branch of Christian theology that seeks to expose and explain and exult the theological unfolding of Holy Scripture, has never been absent from Christ’s people, but the renaissance of biblical theology has come as a signal event in evangelical life and a hallmark of evangelical conviction and preaching.

The centrality of Scripture should be sufficient to remind evangelical believers of this task, but biblical theology receded into the background over much of the twentieth century. Such an approach was central to the theological achievement of John Calvin, that great reformer of Geneva, whose Institutes of the Christian Religion was saturated with what we would now identify as biblical theology. On the other side of the Atlantic, and especially in the Netherlands, towering figures such as Geerhardus Vos dived deeply and faithfully into biblical theology. Similarly, dogmatician Herman Bavick devoted a lifetime to the explication of biblical theology.

Why did biblical theology fall into an eclipse of sorts in the United States? For one thing, American evangelicals were fighting crucial doctrinal battles over truths as essential as the inerrancy, inspiration, and authority of the Bible. Other battles raged over doctrinal essentials such as the virgin birth, the bodily resurrection of Christ, and a host of related doctrines

The last gasp of neo-orthodoxy arrived with the Biblical Theology Movement, but that movement

came largely at the expense of biblical inerrancy and fell apart. Liberal theology just collapsed into social activism and protest theologies. Then came postmodernism and the denial of any over-arching “metanarrative” within the Bible,

But then something unexpected happened. Evangelicals came to understand that a more faithful understanding of biblical authority truly set the stage for a recovery of a genuine approach to biblical theology—one based in full fidelity to the faith once for all delivered to the saints and fully faithful to the authority and inerrancy of God’s Word.

Put most simply, the Bible reveals an unfolding story of God’s purposes as revealed in creation and redemption and the consummation of all things to God’s greater glory. The pattern can be summarized most briefly in two dimensions—as promise and fulfillment. A true biblical theology reveals and explains the unfolding of God’s plan to redeem sinners by the blood of the Lamb. The distinction between law and gospel is made clear, but the consistency of God’s eternal plan is made equally clear.

The recovery of biblical theology in our midst comes with the promise of an even more comprehensive assertion of biblical truth and a clearer understanding of God’s faithfulness and redeeming love. For this recovery I am deeply thankful. It has transformed evangelical preaching and greatly encouraged God’s people. Biblical theology drives us into an even deeper devotion to the Gospel and the old, old story of Jesus and his love.

Fall 2025

Copyright © 2025

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

Vice President of Communications and Managing Editor: Jacob Percy

Creative Director: Samantha Rice

Copy Editor: Hannah Miller

Designer: Ruth Bayles

Production Manager: Drew Watson

Photographers: Mark Schisler, Daniel Villanueva

News Writer: Travis Hearne

Subscription Information: Lexington Road Magazine is published by The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2825 Lexington Road, Louisville, KY 40206. The magazine is distributed digitally at equip.sbts.edu/magazine. If you would like to request a hard copy, please reach out by emailing communications@sbts.edu.

Mail:

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2825 Lexington Road, Louisville, KY 40206

Online: sbts.edu

Email: communications@sbts.edu

Telephone: (502) 897-4000

Cover Art: Interior of the Oude Kerk at Delft during a Sermon, Emanuel de Witte, 1651

10 The Nations in the Storyline of the Bible: A Biblical Theology of God’s Global Mission by Paul Akin

22 Old Testament Interpretation by Daniel Stevens

32 Reading as Discipleship: Why Biblical Interpretation is Meant to Change You by Jonathan T. Pennington

CONVERSATION

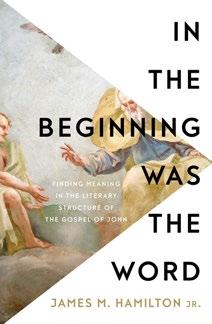

67 Office Hours with James Hamilton

76 Faculty Titles

92 A Chapel Message from Kyle Claunch The Glory of Gethsemane: Christ’s Humanity and Our Hope

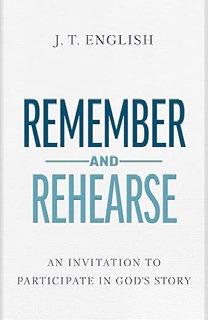

42 A God-Centered Vision for Discipleship by J. T. English

54 The Serpent, the Seed, and the Savior: How Genesis 3:15 Shapes the Whole Bible by Mitchell L. Chase

71 Office Hours with Stephen Wellum

82 The Tradition of SBTS Faculty Writings: An Enduring Vision to “Study with the Authors” by Travis Hearne

But I do not account my life of any value nor as precious to myself, if only I may finish my course and the ministry that I received from the Lord Jesus, to testify to the gospel of the grace of God. And now, behold, I know that none of you among whom I have gone about proclaiming the kingdom will see my face again. Therefore I testify to you this day that I am innocent of the blood of all, for I did not shrink from declaring to you the whole counsel of God.

ACTS 20:24–27 FOUNDATIONS

by R. Albert Mohler, Jr.

Western society is currently experiencing what can only be described as a moral revolution. Our society’s moral code and collective ethical evaluation on a particular issue has undergone not small adjustments but a complete reversal. That which was once condemned is now celebrated, and the refusal to celebrate is now condemned.

What makes the current moral and sexual revolution so different from previous moral revolutions is that it is taking place at an utterly unprecedented velocity. Previous generations experienced moral revolutions over decades, even centuries. This current revolution is happening at warp speed.

As the church responds to this revolution, we must remember that current debates on sexuality present to the church a crisis that is irreducibly and inescapably theological. This crisis is tantamount to the type of theological crisis that Gnosticism presented to the early church or that Pelagianism presented to the church in the time of Augustine. In other words, the crisis of sexuality challenges the church’s

understanding of the gospel, sin, salvation, and sanctification. Advocates of the new sexuality demand a complete rewriting of Scripture’s metanarrative, a complete reordering of theology, and a fundamental change to how we think about the church’s ministry.

Proof-texting is the first reflex of conservative Protestants seeking a strategy of theological retrieval and restatement. This hermeneutical reflex comes naturally to evangelical Christians because we believe the Bible to be the inerrant and infallible word of God. We understand that, as B.B. Warfield said, “When Scripture speaks, God speaks.” I should make clear that this reflex is not entirely wrong, but it’s not entirely right either. It’s not entirely wrong because certain Scriptures (that is, “proof texts”) speak to specific issues in a direct and identifiable way.

There are, however, obvious limitations to this type of theological method—what I like to call the “concordance reflex.” What happens when you are wrestling with a theological issue for which no corresponding word appears in the concordance? Many of the most important theological issues cannot be reduced to merely finding relevant words and their corresponding verses in a concordance. Try looking up “transgender” in your concordance. How about “lesbian”? Or “in vitro fertilization”? They’re certainly not in the back of my Bible.

It’s not that Scripture is insufficient. The problem is not a failure of Scripture but a failure of our approach to Scripture. The concordance approach to theology produces a flat Bible without context, covenant, or master-narrative—three hermeneutical foundations that are essential to understand Scripture rightly.

Biblical theology is absolutely indispensable for the church to craft an appropriate response to the current sexual crisis. The church must learn to read Scripture according to its context, embedded in its master-narrative, and progressively revealed along covenantal lines. We must learn to interpret each theological issue through Scripture’s metanarrative of creation, fall, redemption, and new creation. Specifically, evangelicals need a theology of the body that is anchored in the Bible’s own unfolding drama of redemption.

Genesis 1:26– 28 indicates that God made man—unlike the rest of creation—in his own image. This passage also demonstrates that God’s purpose for humanity was an embodied existence. Genesis 2:7 highlights this point as well. God makes man out of the dust and then breathes into him the breath of life. This indicates that we were a body before we were a person. The body, as it turns out, is not incidental to our personhood. Adam and Eve are given the commission to multiply and subdue the earth. Their bodies allow them, by God’s creation and his sovereign plan, to fulfill that task of image-bearing.

The Genesis narrative also suggests that the body comes with needs. Adam would be hungry, so God gave him the fruit of the garden. These needs are an expression embedded within the created order that Adam is finite, dependent, and derived. Further, Adam would have a need for companionship, so God gave him a wife, Eve. Both Adam and Eve were to fulfill the mandate to multiply and fill the earth with God’s image-bearers by a proper

use of the bodily reproductive ability with which they were created. Coupled with this is the bodily pleasure each would experience as the two became one flesh— that is, one body.

The Genesis narrative also demonstrates that gender is part of the goodness of God’s creation. Gender is not merely a sociological construct forced upon human beings who otherwise could negotiate any number of permutations. But Genesis teaches us that gender is created by God for our good and his glory. Gender is intended for human flourishing and is assigned by the Creator’s determination—just as he determined when, where, and that we should exist.

In sum, God created his image as an embodied person. As embodied, we are given the gift and stewardship of sexuality from God himself. We are constructed in a way that testifies to God’s purposes in this.

Genesis also frames this entire discussion in a covenantal perspective. Human reproduction is not merely in order to propagate the race. Instead, reproduction highlights the fact that Adam and Eve were to multiply in order to fill the earth with the glory of God as reflected by his image bearers.

The fall, the second movement in redemptive history, corrupts God’s good gift of the body. The entrance of sin brings mortality to the body. In terms of sexuality, the Fall subverts God’s good plans for sexual complementarity. Eve’s desire is to rule over her husband (Gen 3:16). Adam’s leadership will be harsh (3:17-19). Eve will experience pain in childbearing (3:16).

The narratives that follow demonstrate the development of aberrant sexual practices, from polygamy to rape, which Scripture addresses with remarkable candor. These Genesis accounts are followed by the giving of the Law which is intended to curb aberrant sexual behavior. It regulates sexuality and expressions of gender and makes clear pronouncements on sexual morals, cross-dressing, marriage, divorce, and host of other bodily and sexual matters.

The Old Testament also connects sexual sin to idolatry. Orgiastic worship, temple prostitution, and other horrible distortions of God’s good gift of the body are all seen as part and parcel of idolatrous worship. The same connection is made by Paul in Romans 1. Having “exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and reptiles” (Rom 1:22), and having “exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator” (Rom 1:25), men and women exchange their natural relations with one another (Rom 1:26-27).

With regard to redemption, we must note that one of the most important aspects of our redemption is that it came by way of a Savior with a body. “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14; cf. Phil. 2:5-11). Human redemption is accomplished by the Son of God incarnate —who remains incarnate eternally.

Paul indicates that this salvation includes not merely our souls but also our bodies. Romans 6:12 speaks of sin that reigns in our “mortal bodies”—which implies the hope of future bodily redemption. Romans 8:23 indicates part of our eschatological hope is the “redemption of our bodies.” Even now, in our life of sanctification we are commanded to present our bodies as a living sacrifice to God in worship (Rom. 12:2). Further, Paul describes the redeemed body as a temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor 6:19) and clearly we must understand sanctification as having effects upon the body.

Sexual ethics in the New Testament, as in the Old Testament, regulate our expressions of gender and sexuality. Porneia, sexual immorality of any kind, is categorically condemned by Jesus and the apostles. Likewise, Paul clearly indicates to the church at Corinth that sexual sin—sins committed in the body (1 Cor 6:18)—are what bring the church and the gospel into disrepute because they proclaim to a watching world that the gospel has been to no effect (1 Cor 5-6).

Finally, we reach the fourth and final act of the drama of redemption—new creation. In 1 Corinthians 15:42-57, Paul directs us not only to the resurrection of our own bodies in the new creation but to the fact that Christ’s bodily resurrection is the promise and power for that future hope. Our resurrection will be the experience of eternal glory in the body. This body will be a transformed, consummated continuation of our present embodied existence in the same way that Jesus’ body is the same body he had on earth, yet utterly glorified.

The new creation will not simply be a reset of the garden. It will be better than Eden. As Calvin noted, in the new creation we will know God not only as Creator but as Redeemer—and that redemption includes our bodies. We will reign with Christ in bodily form, as he also is the embodied and reigning cosmic Lord.

In terms of our sexuality, while gender will remain in the new creation, sexual activity will not. It is not that sex is nullified in the resurrection; rather, it is fulfilled. The eschatological marriage supper of the Lamb, to which marriage and sexuality point, will finally arrive. No longer will there be any need to fill the earth with image-bearers as was the case in Genesis 1. Instead, the earth will be filled with knowledge of the glory of God as the waters cover the sea.

The sexuality crisis has demonstrated the failure of theological method on the part of many pastors. The “concordance reflex” simply cannot accomplish the type of rigorous theological thinking needed in pulpits today. Pastors and churches must learn the indispensability of biblical theology and must practice reading Scripture according to its own internal logic— the logic of a story that moves from creation to new creation. The hermeneutical task before us is great, but it is also indispensable for faithful evangelical engagement with the culture.

by Paul Akin

The Bible presents us with an alternative story—a different way of seeing and understanding the world around us. It is not merely a local tale about a particular ethnic group or a narrow religious tradition. Instead, the Bible presents us with the story of the world itself: a story that begins with the creation of all things and will be complete with the restoration and renewal of all things. The biblical story declares that God’s plan and purpose is for our lives to be shaped, formed, and transformed by this divine narrative.

From a Baptist perspective, we recognize that this story is not fragmented or accidental. God is sovereign over history, and every page

of Scripture reveals His eternal purpose to glorify Himself by redeeming a people for His name from every tribe, tongue, and nation. The nations are not a side note in the Bible; they are central to the unfolding story of redemption.

The story of the Bible develops in four major movements: creation, fall, redemption, and restoration. Together, these essential elements of the story form the framework for understanding God’s mission and the place of the nations within His plan. With each unfolding component, the storyline of the Bible becomes increasingly clear. The story begins at the beginning of the Bible in creation.

Creation: God’s Good World and His Image-Bearers

Genesis opens with simplicity and clarity: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth”

(Gen 1:1). The triune God—Father, Son, and Spirit— speaks the world into existence out of nothing. In the opening pages of the Bible, we learn that God is eternal, self-sufficient, and sovereign over all. Creation is distinct from God, yet dependent upon Him. Everything He makes is declared “very good” (Gen 1:31). Humanity, the crown of creation, is uniquely made in the imago Dei —the image of God.

At the outset, humanity is flourishing in every facet and relationship. First, humanity has a perfect relationship with God. Humanity was created to know, love, and worship its Creator. Second, humanity has a perfect relationship with one another. Humanity is designed for community and love of neighbor. Third, humanity has a perfect relationship with oneself. Humanity is called to see itself rightly, through God’s eyes, with dignity and humility. Lastly, humanity has a perfect relationship with creation. Humanity is tasked to steward, cultivate, and develop God’s good world.

The mandate given in Genesis 1:28, “Be fruitful, multiply, fill the earth, and subdue it”—is global in scope. From the very beginning, God’s plan was for His image-bearers to spread across the earth, reflecting His glory in every corner of creation. This is the original “mission” that God gives to his people. At this point in redemptive history, Adam and Eve are dwelling in perfect union and harmony with the Triune God.

Genesis 3 records the tragic reversal. Adam and Eve reject God’s word, choosing autonomy and self-rule. In an effort to pursue power and happiness apart from God’s plan, they plunge the world into sin and death. This seemingly harmless act of rebellion resulted not only in Adam and Eve’s fall from God’s purpose and will, but also the fall of the entire created order.

As a result of Adam and Eve’s sinful rebellion, humanity in every facet is now affected negatively by the fall. The consequences of sin impact every key

relationship. First, a broken relationship with God. Humanity becomes alienated from its Creator, now described as children of wrath (Eph 2:3). Second, a broken relationship with others. Strife, jealousy, and violence characterize human relationships (Gen 4: Cain and Abel). Third, a broken relationship with oneself. The image of God is marred; our loves are disordered; pride and shame reign in our hearts. Lastly, a broken relationship with the created order. Work becomes toilsome, and creation itself groans under the curse (Rom 8:20–22). Most pointedly, the punishment for sin is death.

Yet even in judgment, God offers a glimmer of hope. In Genesis 3:15, God promises that the seed of the woman will crush the serpent’s head. The Protoevangelium (first gospel) anticipates Christ, the Redeemer, who will undo the works of the devil. From this point forward, the story of the Bible is the story of how God unfolds this promise, progressively revealing His plan to bless the nations through His chosen people.

Despite human rebellion and the tragic effects of sin and the fall, God’s purpose advances in his mission of redemption. In Genesis 12:1–3, God calls Abram and makes a covenant with him: “I will make you into a great nation, I will bless you, I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing… . and all the peoples on earth will be blessed through you.” Here, the scope of God’s mission comes into focus. The promise is twofold: God will make Abraham’s descendants into a great nation, and through that nation He will bless all the nations of the earth. This covenantal theme runs through the patriarchs—Isaac and Jacob—and shapes the rest of redemptive history.

Even the patriarchal narratives reveal threats to God’s plan—barrenness, famine, hostile kings, and unbelief. Yet God’s faithfulness continually shines

through. He preserves His people in Egypt through Joseph’s trials, showing that He is sovereign over history and committed to His redemptive purpose. Towards the conclusion of the book of Genesis, Jacob moves his twelve sons and their families to Egypt to escape a famine. It is in Egypt several hundred years later that God demonstrates His faithfulness to His mission, His plan, and His purposes.

The Exodus is the great act of redemption in the Old Testament. God delivers His people from slavery in Egypt, defeats Pharaoh, and reveals His supremacy over the gods of the nations. At Sinai, He establishes Israel as His covenant people, giving them a distinct identity and mission (Exod 19:3–6). Through Moses, God calls the people of Israel to be a Kingdom of Priests and a Holy Nation. First, as a Kingdom of Priests, Israel is to mediate God’s presence and blessing to the peoples and nations of the world. Second, as a Holy Nation, Israel is to display the beauty of life under God’s rule and reign. Israel is called to be a showcase people who reveal what it means to live in covenant relationship with Yahweh. The law was given not as a means of salvation, but as a guide for Israel’s role and a constant reminder to live distinctly in a watching world.

Yet the Bible repeatedly demonstrates that Israel continually falls short of the task given to them by God at Sinai. The books of Judges, Kings, and Chronicles trace a downward spiral of idolatry, rebellion, and disobedience. Instead of serving as a blessing to the nations, Israel becomes indistinguishable from them. The idolatry and rebellion of Israel eventually led to the devastating experience of exile.

In the period of exile, Israel is left wondering what has happened to the promises that God made to the patriarchs. However, even during the time of exile, God continues to speak to His people through the prophets. Through the prophets, God promises a

coming King from David’s line who will bring justice, peace, and global salvation (Isa 9:6–7). He declares that His intention remains that His people would function as a light to the nations (Isa 49:6).

Nevertheless, Israel eventually returns to the land but resettles on a much smaller scale and faces mounting challenges all around it. Between the end of the Old Testament and the beginning of the New Testament, there is a period of silence from God that lasts more than four hundred years. During this time, Israel had to wonder what God’s plans and purposes were for His people. Would God keep the promises that He had made to the patriarchs? Would Israel be a light to the nations and bless the peoples and nations of the earth?

It is in this context of uncertainty and expectation that Jesus of Nazareth arrives on the scene. He proclaims the arrival of God’s kingdom and demonstrates it through teaching, miracles, and acts of compassion. Unlike Israel, Jesus perfectly embodies the calling to be a light to the nations. But His mission is not accomplished through political triumph or military might. Instead, Jesus’s mission is fulfilled through His atoning sacrifice on the cross. In His substitutionary death, Jesus bears the penalty of sin, satisfying the wrath of God and making it possible for sinners to be reconciled to God through repentance and faith. As Paul declares, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us … so that the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:13–14).

Jesus’s resurrection from the dead vindicates Him as Lord and inaugurates the new creation. His authority now extends to heaven and earth, and with that authority He commissions His disciples: “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations” (Matt 28:19). The global scope of God’s mission could not

be clearer. The church is now entrusted with the task once given to Israel: to be a holy people and to declare the excellencies of the One who called them out of darkness and into his marvelous light (1 Pet 2:9).

The book of Acts records the Spirit-empowered expansion of the gospel. Beginning in Jerusalem, then Judea and Samaria, and finally to the ends of the earth, the good news spreads across the Roman Empire. The apostle Paul becomes God’s chosen instrument to bring the gospel to the nations (Acts 9). He plants churches, writes letters, and trains leaders, leaving a missionary legacy that shapes the identity of the church to this day. From the book of Acts to our contemporary moment, the story of God’s people growing in number and gathering from all the nations has continued for 2000 years and continues through us today.

The storyline of Scripture finds its climactic vision in Revelation 5. John sees the Lamb who was slain, worthy to open the scroll of history. The song of heaven declares: “You were slaughtered, and you purchased people for God by your blood from every tribe and language and people and nation” (Rev 5:9). John sees in this vision the fulfillment of God’s covenant promise to Abraham. The nations are not an afterthought; they have always been central to God’s mission of redemption. Christ’s blood secures a people from every corner of the globe, forming a kingdom of priests who will reign with Him forever in the new creation.

The final movement of the biblical story is restoration. Christ will return to judge the living and the dead, to banish Satan forever, and to renew creation. What was lost in Eden will be regained—and more. Genesis

began with creation and a garden; Revelation ends with a new creation and a city, where God’s presence fills every corner (Rev 21–22). The nations, once scattered at Babel and separated by sin, are now gathered as one redeemed people.

The nations in the storyline of the Bible remind us that God’s mission has always been global in scope. From creation’s mandate to fill the earth with His glory, to the covenant with Abraham, to the commissioning of the church, God’s purpose has been to gather a people from every tribe, tongue, and nation.

The Bible is clear that this mission is God’s work from beginning to end. Salvation belongs to the Lord; He sovereignly calls, redeems, and preserves His people. Yet He graciously invites and includes us in His mission, calling the church to proclaim the gospel to all peoples.

Until Christ returns, the church is called to bear witness—to be a holy nation and a royal priesthood— so that the nations might see the glory of God in the face of Christ. The story ends with a multitude that no one can number, from every nation, worshiping the Lamb (Rev 5). The question that remains for us is this: Will we live our lives aligned with this story, God’s story, the story of the nations, and His global mission? May God, by the power of His Spirit, give us grace to be faithful and obedient to the task he has put before us until Jesus returns.

by Stephen J. Wellum

How does all Scripture point to Christ? The answer to this question is important because it also demonstrates how the entire Bible finds its unity, coherence, and center in Christ’s person and work. Despite Scripture being written by numerous authors over many centuries, it is centrally about one thing: what our triune God has planned in eternity, executed in time, in order to redeem a people for himself and to make everything new in Christ Jesus (Eph 1:9–10). To demonstrate how all Scripture points to Christ is to validate this crucial point, but how?

My initial answer is not in terms of hidden verses or codes, or multiple layers of meaning. Instead, all Scripture points to Christ as it traces out God’s redemptive plan, rooted in eternity, enacted in time,

and unveiled over time by human authors. Christ is revealed in all Scripture by starting where the Bible begins—in creation, starting with who God is as Creator and Lord, humans as image-bearers created to know God in covenant relationship, the entrance of sin into the world, and God’s gracious promise and determination to redeem a people for himself by a greater Adam who is not merely human but also the divine Son.

In other words, all Scripture points to Christ by seeing him unveiled in the Bible’s story and discovering how in God’s eternal plan, all of God’s promises, along with various persons, events, and institutions, were intended by God to anticipate, foreshadow, and typify the eternal Son to come. Thus, by tracing out the Bible’s story, the identity of Christ as the divine Son who will assume our human nature to redeem us and why he, as God the Son, must do so, is unveiled step-by-step. In fact, all of Scripture is needed to fully grasp Jesus’s person and work.

“To discover how all Scripture points to Christ, we must first start with who God is, since we cannot know who Jesus is, especially as the divine Son, apart from starting with theology proper. Much could be said on this point, but we begin with God as our Creator and covenant Lord.”

Jesus does not come to us de novo. Instead, he is revealed to us rooted in the teaching and categories of the Old Testament (OT).

To show how all Scripture points to Christ, I will sketch four truths, grounded in the Bible’s story that illustrates how Jesus’s identity as God the Son incarnate is gradually unveiled in the OT, which then comes to full light in the New Testament (NT) in the Son’s incarnation and work.

To discover how all Scripture points to Christ, we must first start with who God is, since we cannot know who Jesus is, especially as the divine Son, apart from starting with theology proper. Much could be said on this point, but we begin with God as our Creator and covenant Lord.

From Genesis 1 on, God presents himself as the uncreated, independent, self-sufficient one who creates and rules all things by his Word (Gen 1–2; Ps 50:12–14; Acts 17:24–25; cf. John 1:1). This truth grounds the central distinction of Christian theology: The Creator-creature distinction, which establishes a specific view of the God-world relationship. God alone is God; all else is creation that depends totally on him for all things. God’s transcendent lordship (Ps 7:17; 9:2; 21:7; 97:9; 1 Kgs 8:27; Isa 6:1; Rev 4:3) also eliminates any notion of deism that rejects God’s agency in human history; God is transcendent and immanent

with his creation. As Creator and Lord, God is fully present and related to his creatures: He freely, powerfully, and purposefully sustains and governs all things to his desired end (Ps 139:1–10; Acts 17:28; Eph 1:11), but he is not identified with the world.

As the Creator, God sovereignly rules over his creation. He rules with perfect power, knowledge, and righteousness (Ps 9:8; 33:5; 139:1–4, 16; Isa 46:9–11; Rom 11:33–36). As Lord, God acts in, with, and through his creatures to accomplish his plan and purposes (Eph 1:11). As personal, God commands, loves, comforts, and judges consistent with himself and according to the covenant relationships that he establishes with his creatures. In fact, as Scripture unfolds over time, God discloses himself as tri-personal, a unity of three persons: Father, Son, and Spirit (Matt 28:18–20; John 1:1–18; 5:16–30; 17:1–5; 1 Cor 8:5–6; 2 Cor 13:14; Eph 1:3–14). In fact, the Trinity is revealed with the unveiling of Christ as the divine Son, along with the Holy Spirit as God.

God is also the Holy One (Gen 2:1–3; Exod 3:2–5; Lev 11:44; Isa 6:1–3; Rom 1:18–23). God’s holiness means more than “set apart.” God’s holiness is uniquely associated with his aseity (“life from himself”). As God, he is selfsufficient metaphysically (self-existent) and morally (self-justifying; he is the moral standard of the universe). God is categorically different in nature and existence than his creation; he shares his glory with no one (Isa 40–48).

God’s holiness entails his personal moral perfection. He is “too pure to behold evil” and unable to tolerate wrong (Hab 1:12–13; cf. Isa 1:4–20; 35:8). As such, God must act with holy justice when his people rebel against him; yet he is the God who loves his people with a holy love (Hos 11:9). God’s holiness and love are never at odds (1 John 4:8; Rev 4:8). Yet, as sin enters the world in Adam, and God graciously promises to redeem us, a question arises as to how he will do so and remain true to himself—a question central to the Bible’s unveiling of Christ’s identity.

This summary of theology proper is the first truth that is crucial in how all Scripture points to Christ. Specifically, Jesus’s identity is tied to this God, and it is within this framework that Christ’s identity is unveiled. But why is this significant for understanding how all Scripture reveals Christ? Let me offer two important reasons.

First, as the Bible’s story unfolds, beginning in Genesis 3:15—the seed of the woman—and then, especially in the prophets, the Messiah-Son to come will be human but also identified with God. For it is he who will fulfill all of God’s promises, inaugurate God’s saving rule, and share God’s throne (Ps 110; cf. Ps 45)—something no mere human can do.

In fact, one of the ways the NT teaches Christ’s deity is by identifying Jesus with OT Yahweh texts and applying them directly to him, thus identifying Jesus with this God (Rom 10:9; 1 Cor 12:3; Phil 2:11). Also, in the NT, theos is applied to Christ seven times, but when set in the context of the OT, this identifies Jesus with God. In biblical thought, no creature can share the attributes of God (Col 2:9), carry out the works of God (Col 1:15–20; Heb 1:1–3), receive the worship of God (John 5:22–23; Phil 2:9–11, Heb 1:6; Rev 5:11–12), and bear the titles and name of God (John 1:1, 18; 8:58; 20:28; Rom 9:5; Phil 2:9–11; Heb 1:8–9) unless he is God equal with God, and thus one who shares the one, identical divine nature.

BY S TEPHEN J. W

Second, given that God is the moral standard, then sin before God is a serious problem. As the holy one, God is “the Judge of all the earth” who always does what is right (Gen 18:25). But in promising to justify us before him (Gen 15:6; Rom 4:5), God cannot overlook our sin; he must remain true to his own righteous demand against sin. But how can God remain just and the justifier of the ungodly? In Scripture, this is the major question that drives the Bible’s story. Ultimately, as God’s plan unfolds, this question is answered in a specific person, namely, the Messiah, who is the Servant-Son, who alone can redeem us because he is more than a mere man. He is also the divine Son who becomes human to act as our representative and substitute (Rom 3:21–26). As the divine Son, he is able to satisfy his own righteous demand against us, and as human, he is able to satisfy the demands of covenant life for us as our new covenant head.

To grasp how all Scripture reveals Christ, we must also identify humans rightly as God’s image-sons and covenant creatures. Specifically, we must go back to Adam and then trace the Bible’s link between the command to and the curse of the first Adam that is remedied only by the last Adam. Otherwise, we cannot make sense of why the divine Son became man to save us from our sins (Matt 1:21) and how the Bible’s story, starting with Adam, anticipates Christ.

Scripture divides all humans under two representative heads: Adam and Christ (Rom 5:12–21; 1 Cor 15:12–28). In God’s plan, Adam is a type of Christ, who anticipates the last Adam (Rom 5:14).

Adam is not only the first man, but also humanity’s representative. Adam’s headship defines what it means to be human, and sadly, by his representative-legal act of disobedience, he plunges all people into sin (Gen 3; Rom 3:23; 5:12–21).

Central to God’s relationship with us is his demand of obedience. From Adam, and by extension all of us, God demands complete obedience. After all, what else would God demand as our Creator? Also, God enters into a covenant relationship with Adam. God gives him a command (Gen 2:15–17) and a promise that if he obeys, he will be confirmed in permanent covenant fellowship with God. The tree of the knowledge of good and evil tests whether Adam will be an obedient covenant keeper. Tragically, Adam disobeys, and the consequence of his action is not private. Post-fall, all people are born “in Adam”— guilty and corrupt. Also, Adam’s sin impacts the entire creation; we now live in a fallen, abnormal world that requires God to remedy (Gen 3:15; Rom 8:18–25). The tree of life holds out an implied promise of life. Yet, because of sin, the Judge of all the earth expels Adam from Eden. Yet, there is a concealed message of hope in God’s promise to provide a Redeemer (Gen 3:15), which, over time, is unveiled with greater understanding through the biblical covenants. Why is this important for how Christ is in all Scripture? Because of the truth of who Adam is, his disobedience that results in sin and death, and God’s gracious promise to redeem and to provide a coming Redeemer drive the Bible’s story. It gives the rationale for why the divine Son must become incarnate for us, and why he must be greater. Why? Because to undo and to pay for Adam’s sin, the “seed of the woman” must come. For redemption to occur, a human must do it. He must render our required covenantal obedience as a greater Adam. Yet, the reversal of Adam’s sin and all of its disastrous effects will require more than a mere man. It will also require the divine Son, the true image of God (Col 1:15; Heb 1:3), to do the work of God: to remove the curse, to pay for our sin, and to usher in a new creation. To underscore why the reversal of Adam’s sin will require more than a mere human, let’s turn to the third truth.

Central to the purpose of our creation and the covenant is that God has created us to know him and to be his image-sons to display his glory by expanding Eden’s borders to the entire creation. But what happens when we rebel against God and deface the image? Can the divine purpose still be accomplished? How will God forgive those who sin against him?

From Genesis 3 on, Scripture reveals that Adam’s disobedience brought sin into the world and all humans under God’s wrath. God expels Adam and Eve from his presence, and sin’s transmission is universal. By Genesis 6, human sin has so multiplied that it results in a global flood. Looking back on the course of human history, Paul confirms our universal fallenness: “There is no one righteous, not even one … for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom 3:10, 23). Adam’s sin turned the created order upside down and brought on us the sentence of death (Rom 6:23). We were made to know, love, and serve God. But now we live under his righteous condemnation as his enemies and objects of his wrath (Eph 2:1–3).

What is God’s response to our sin? Judgment, yet given God’s promise to redeem, there is also grace and provision. But how can God do both: judge us yet also forgive us of our sin? God is holy and just, sin is against him, and sin must be punished. God cannot and will not overlook our sin since our sin is not against an impersonal law, but against him (Ps 51:4). For God to forgive us, it will demand nothing less than the full satisfaction of his moral demand. But who is able to satisfy God’s righteous demand other than God himself?

These three truths are foundational to the Bible’s story and necessary to grasp if we are to understand how all Scripture reveals Christ. First, because of who God is and his promise to save, he must provide his own solution to the forgiving of our sin. Second, because God has created humans to rule over creation, salvation must come through a man. Third, because

of the universal nature of sin, this last Adam must be greater than the first, and ultimately, God himself. In other words, the Redeemer to come must identify with God in his nature and with us in ours—a point that is underscored in the unfolding of the covenants.

God Himself Saves through His Obedient Son

Who, then, is qualified to undo what Adam did, establish God’s kingdom on earth, and save us from our sins? Certainly, no one “in Adam” is able to do so, but there is one who can: God’s own provision of his Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, which is unveiled through the covenants.

After Adam’s sin, God does not leave us to ourselves. God acts in grace and promises to reverse the manifold effects of sin through his provision of the “seed of the woman” (Gen 3:15)—a promise that is given greater clarity over time. We learn that this coming Redeemer will destroy the works of Satan and restore goodness to this world. This promise creates the hope that when it’s finally realized, sin and death will be destroyed, and the fullness of God’s saving reign will come. As God’s plan unfolds, we discover who this Redeemer is and how he will save us. Three points will develop this last point.

First, God’s promise of the coming of the “seed of the woman” is unfolded through the covenants with Noah, Abraham, Israel, and David, which develop and anticipate the promise.

Gradually, God prepares his people to anticipate the coming of a person who will be human but also more. How? Scripture teaches that the fulfillment of God’s promises will be through a human, anticipated by various typological persons such as Adam, Noah, Moses, Israel, and David, along with the development of the priesthood, sacrificial system, and temple. But Scripture also identifies this Messiah with God. How? Because of what this Messiah-King does: he inaugurates God’s rule, shares God’s throne, and does what only God can do (e.g., Pss 2, 45, 110; Isa 9:6–7; Ezek 34).

Second, how does God’s kingdom come in its redemptive-new creation sense (Isa 65:17)? As the OT unfolds, God’s saving kingdom is revealed and comes to this world, at least in anticipatory form, through the covenants and their heads—Adam, Noah, Abraham and his seed, Israel, and most significantly through David and his sons. Yet, the OT repeatedly reminds us that these covenant heads disobey; they are not the promised “seed of the woman.” Specifically, this is evident in the Davidic covenant and kings.

The Davidic covenant is the epitome of the OT covenants; it brings the previous covenants to a climax in the king. There are two main parts to it: (1) God’s promises about the establishment of David’s house forever (2 Sam 7:12–16), and (2) the promises concerning the “Fatherson” relationship between God and

BY S TEPHEN J. W ELLUM

“After Adam’s sin, God does not leave us to ourselves. God acts in grace and promises to reverse the manifold effects of sin through his provision of the ‘seed of the woman’ (Gen 3:15)—a promise that is given greater clarity over time.”

the Davidic king (2 Sam 7:14; cf. Ps 2; 89:26–27).

The meaning of this “sonship” is twofold. First, it inextricably ties the Davidic covenant to the previous covenants, and second, it anticipates in type the greater Sonship of Christ.

Regarding the former, the sonship applied to corporate Israel (Exod 4:22–23; cf. Hos 11:1) is now applied to the individual Davidic king, who, in himself, is “true Israel.” He becomes the administrator of the covenant, thus representing God’s rule to the people and representing the people as a whole (2 Sam 7:22–24). This also entails that the Davidic king fulfills the role of Adam; it is through him that God’s rule is effected in the world (2 Sam 7:19b). This makes sense if one links the covenants together, building toward climactic fulfillment. At the center of God’s redemptive plan is the restoration of humanity’s vice-regent role in creation via the seed. By the time we reach David, we now know that it is through the Davidic king that creation will be restored. In the OT, this truth is borne out in many places, especially the Psalter, which envisions the Davidic son as executing a universal rule (e.g., Ps 2, 8, 45, 72, cf. Isa 9:6–7, 11, 53).

But in OT history, there is a major problem. As previous covenant mediators disobeyed, so also the Davidic kings. Yet the hope of salvation depends on them. God continues in his unilateral determination to keep his promise to bring forth the promised king who will rule the world, yet there is no faithful sonking who effects God’s saving reign. This leads to the message of the Prophets and the anticipation of a new covenant.

When thinking of the OT writing prophets, it is crucial to note that all of them wrote post-David. Why is this important? Their prophecies build on what God has already revealed through the covenants in promises and typological patterns. The prophets not only speak of God’s judgment on the nation for their violation of the covenant, but they also proclaim an overall pattern of renewal by recapitulating the past

history of redemption and projecting it into the future. The prophets announce that God will unilaterally keep his promise to redeem and he will do so through a faithful Davidic king (Isa 7:14; 9:6–7; 11:1–10; 42:1–9; 49:1–7; 52:13–53:12; 55:3; 61:1–3; Jer 23:5–6; 33:14–26; Ezek 34:23–24; 37:24–28). In this king, identified as the “servant of Yahweh,” a new/everlasting covenant will come, and with it the pouring of the Spirit (Ezek 36–37; Joel 2:28–32), God’s saving reign among the nations, the forgiveness of sin (Jer 31:34) and a new creation (Isa 65:17). The hope of the Prophets is found in the new covenant, which at its heart promises the full forgiveness of our sins (Jer 31:34).

Third, we can now see how the Bible’s covenantal story identifies and anticipates Christ. If we step back and ask— Who is able to fulfill all of God’s promises, inaugurate God’s saving rule in this world, and achieve the full forgiveness of sin? Answer: God alone. And this is precisely what the OT teaches (Isa 43:11; 45:21).

As Israel’s history unfolds, it becomes evident that God alone must act to accomplish his promises; he must initiate in order to save; he must unilaterally act if there is going to be redemption at all. After all, who can achieve the forgiveness of sin other than God alone? Who can usher in the new creation, final judgment, and salvation? If there is to be salvation, God himself must come and usher it in and execute judgment (Isa 51:9; 52:10; 53:1; 59:16–17; cf. Ezek 34).

Just as God once led Israel through the desert, so he must come again, bringing a new exodus to bring salvation to his people (Isa 11:10–16; 40:3–5; 43:1–7; cf. Hos 11:1–12).

However, as the covenants establish, alongside the emphasis that God himself must come to redeem, the OT also stresses that God will do so through another David, a human “son,” but a “son” who is also closely identified with Yahweh. Isaiah pictures this well. This king to come will sit on David’s throne (Isa 9:7) but he will also bear the very titles/names of God (Isa 9:6). This King, though another David (Isa 11:1),

is also David’s Lord who shares the divine rule (Ps 110:1). He will be the mediator of a new covenant; he will perfectly act like Yahweh (Isa 11:1–5), yet he will suffer for our sin to justify many (Isa 53:11). In him, OT hope and expectation is joined: God must save but through his King-Son—who is truly human yet one who bears the divine name.

So how does all Scripture reveal Christ? It does so by the unveiling of this covenantal story, which step-by-step reveals what is concealed. In fact, as the NT opens, and Jesus arrives on the scene, this is precisely how the NT presents him. Jesus is the human son (Matt 1:1—“son of David and Abraham), yet he is also the eternal, divine Son of the Father, identified with God who has come to save his people from their sins (see Matt 1:21; 11:1–15; 12:41–42; 13:16–17; Luke 7:18–22; 10:23–24; cf. John 1:1–3; 17:3). As the human son, he perfectly fulfills all the typological patterns and roles of the previous sons for our salvation (e.g., Adam [Luke 3:38], Israel [Exod 4:22–23; Hos 11:1], David [2 Sam 7:14; Pss 2, 16, 72, 110]). By his incarnation and work, he becomes David’s greater Son, the last Adam, who inaugurates God’s kingdom, and is now seated as the Davidic king, leading history to its consummation at his return (Matt 1:1; 28:18–20; Luke 1:31–33; Rom 1:3–4; 5:12–21; 1 Cor 15:22–22; Eph 1:9–10, 18–23; Phil 2:9–11; Col 1:15–20; Heb 1–2). Yet, Jesus can only do all of this because he is the divine Son of the Father (Matt 11:25–30; John 5:16–30) who assumed our humanity and lives, obeys, dies, and is raised for our justification. For it is only as the divine Son assuming our human nature that he can fulfill all of the Law and the Prophets (Matt 5:17–20; 7:12) and take on himself our sin, guilt, and make this world right by the ratification of a new covenant in his blood (Rom 3:21–26; 5:1–8:39; 1 Cor 15:1–34; Eph 1:7–10; Heb 8:1–13). In this way, from beginning to end, Scripture reveals Christ.

by Daniel Stevens

Ihave often had an uneasy relationship with the Old Testament. I have loved it for its wild poetry and intricate narrative. I have striven to see it as it came to Israel and was received in unfolding splendor. And so, throughout much of my Christian life thus far, while I have been able to see the Old Testament as God’s Word to Israel and as a densely woven set of storylines and movements that find resolution in the New Testament, I have had difficulty moving back from the New Testament to the Old Testament.

When I saw the New Testament’s use of Old Testament passages, I became confused. I held the apostles’

interpretations at arm’s length because it seemed that they were seeing what was not there. I knew the apostles could not be wrong in their inspired writing, so for years I attributed this seemingly creative strand of interpretation to their role as prophets. Matthew was right to say that Jesus’s flight to Egypt and return as a child fulfilled the words of Hosea (Matt 2:15; Hos 11:1), but there is no way we could have known that. God let them see what we otherwise could not. We should not go one letter beyond what they said and saw anew. How could we?

I had thought my problem was strictly with the New Testament and its ways of reading. In truth, I did not yet understand the Old Testament for what it really was. I had not yet learned to read the books of the old covenant as Christian Scripture.

What I mean by this is that I had failed to appreciate the ways in which the whole Scripture, Old and New, works together. The same God who inspired the Old Testament inspired the New Testament, and knew what he would have the apostles say as they reflected on the prophets. Just because the original audience would not have been able to understand the full significance of a given prophecy did not mean that the significance was not there. Rather, God put some things within the Old Testament as a mystery, waiting to be made clear in the fullness of revelation with the coming of Christ.

As I studied the book of Hebrews for my doctorate, I was confronted again and again with the author’s way of interpreting the Old Testament Scriptures. Perhaps more than any other book in the New Testament, Hebrews presents itself as a long and careful engagement with the words of the Old Testament. Every claim about Jesus, every argument about the responsibilities of the audience, and every statement about the new reality that has come after Jesus’s life, death, resurrection, and ascension is grounded in what God said in the Old Testament. Nothing is presented as an innovation, but rather the author repeatedly claims to be interpreting God’s Word. Further, the author never depends on his own personality or apostolic authority to drive home a point. It is upon the interpretation of the Scriptures that everything in Hebrews is founded.

He may see things that others have not seen before, but he is not reading them into the passages. Further, he expects his audience (and God expects us) to agree not just with his conclusions, but with his interpretations. That means in Psalm 2, we have the Father speaking to the Son (Heb 1:5). In Psalm 45 and Psalm 102, we have what God says about the Son (Heb 1:8–12). In Psalm 22, we have Jesus’s own words (Heb 2:12). This is not a claim to prophetic new information, but rather, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, the author of Hebrews is reading the

Old Testament and seeing what is really there. And the more we pay attention to how and what he does, the more we see that he is paying close and careful attention to the actual words of the passage. He is interpreting and showing us how to interpret.

That is, he reveals to us both how to read the Old Testament and what the Old Testament really is: God’s Word, written for us. The one God who spoke to the fathers through the prophets has spoken to us in his Son (Heb 1:1–2). But we see that speech to us in the very words of Scripture, both Old and New.

And once I saw this in Hebrews, I saw it everywhere

Paul tells us that the events of the Exodus took place “as examples for us” (1 Cor 10:6), and that they “were written down” by Moses, so many years ago, “for our instruction, on whom the end of the ages had come” (1 Cor 10:11).

Did you catch that? Why did God have Moses write the Pentateuch? One answer, and one which is most relevant for us, is that Moses wrote the Pentateuch to instruct Christians, we who live at the end of the ages between the first and second comings of Christ. This, Paul says, is what these things were written down for. And it is significant that he says this immediately after an enigmatic interpretation of an Old Testament passage. He makes a parallel between the experiences of the generation of the Exodus and the experience of the church, calling their passing through the Red Sea a kind of baptism (1 Cor 10:2), He then goes on to say not only that they drank “spiritual drink” from the rock (1 Cor 10:4), but that “the Rock was Christ” (1 Cor 10:4). What he means by this may be a bit obscure, but for our purposes, there are some clear implications. The things that happened to the Exodus generation were sovereignly intended by God to point forward to realities about Christ and the church. And in God’s inspiration of the Scriptures

about these events, he designed the very details of the passages to point forward to Christian realities. These things have always been there, for “these things happened to them as an example, but they were written down for our instruction, on whom the end of the ages has come” (1 Cor 10:11).

Similarly, in a well-known passage, on the road to Emmaus, Jesus speaks to the two disciples on the road and “beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he interpreted to them in all the Scriptures the things concerning himself” (Luke 24:27). Now, while this does not say that every verse of every passage is about Jesus, it does say that “in all the Scriptures,” that is, in every book, there are things about Jesus for us to find. These things are already there, and if we interpret them as the resurrected Jesus taught his disciples to interpret, we will see them there.

In his earthly ministry, Jesus also taught and assumed that a right reading of the Old Testament would lead one not only to a vague understanding that Jesus would come but rather to an accurate knowledge of him. When confronting some Jewish leaders, he boldly told them, “You search the Scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life, and it is they that bear witness about me” (John 5:39). Or again, when speaking of his nearing betrayal, death, and resurrection, he asked in Jerusalem, “Have you not read this Scripture: ‘The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone; this was the Lord’s doing, and it is marvelous in our eyes?’” (Mark 12:10–11).

Notice again the precise wording: “Have you not read this Scripture?” He assumes that they should know about him, about his rejection by men but approval by God, from having read Psalm 118. The psalm is about him, and rightly reading the psalm leads to rightly recognizing Christ.

It is not just that the Old Testament historically led to the New Testament as a kind of prelude, but rather that the one God who speaks in both

Testaments intended them to belong forever to the church as a single body of Scripture. That is, while it is important—necessary even—to read the Old Testament as that which went before the coming of Christ and his gospel in all its historical rootedness as God interacted with Israel, it is just as necessary to read it alongside the New Testament as God’s present Word to the church. God spoke in the Old Testament, yes, and in that historical speech, God still speaks.

That is fundamentally what the New Testament authors knew; and that is the key to seeing, as they did, the many-splendored revelation of God in Christ that reverberates through every page of Scripture, Old and New.

The whole Bible is the Word of God for us. It all speaks of Christ. It all speaks to us because God has spoken to us through it.

Adapted from an article by Daniel Stevens entitled, “The Breakthrough That Helped Me Understand the Old Testament.” Used by permission of Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers, Wheaton, IL 60187, www.crossway.org.

“That is, he reveals to us both how to read the Old Testament and what the Old Testament really is: God’s Word, written for us. The one God who spoke to the fathers through the prophets has spoken to us in his Son (Heb 1:1–2). But we see that speech to us in the very words of Scripture, both Old and New.”

by Oren R. Martin

Biblical and systematic theology are not foes, but friends, for they work together to form whole disciples of Christ, who by his Spirit follow him in every area of life. There has always been disciplined, systematic reflection on the history of redemption as it concerns God and his work in Christ. For example, the early church Trinitarian and Christological debates involved putting the whole canon together in light of salvation history as they sought to answer questions of who God is, what he has done in redemption, and how Christ Jesus and the Holy Spirit were identified with God. Then, they sought to address the

contemporary issues of their day, which, in one sense, is a department of systematic theology, as it involved constructive formation against destructive views. Yes, biblical and systematic theology have been friends from the beginning, so what God has joined together let no one separate.

What follows is a brief sketch of biblical (BT) and systematic theology (ST) in order to demonstrate how they differ but work together for our formative good.

Biblical theology works intertextually by tracking how Scripture develops on its own terms as it historically and redemptively unfolds in Christ from Genesis to Revelation. From this description, four convictions of biblical theology are worth noting.

First, biblical theology takes into account the unity of God’s revelation. Scripture is God’s Word written, which reveals his unified plan of redemption from beginning to end. However, God’s redemptive plan did not happen all at once, so his revelation did not come all at once. Rather, “God spoke to our fathers by the prophets at many times and in many ways” (Heb 1:1) as he guided them toward his final— and better—redemption in Christ. This framework presupposes that Scripture constitutes a unified text with a developing story. God’s Word reveals and interprets his redemptive acts that develop across time, from creation to consummation. Therefore, biblical theology must keep the redemptive-revelatory and redemptive-historical nature of Scripture in its focus. But not only is God’s revelation redemptivehistorical, but it is also eschatological. That is, it has a divine goal. Michael Horton is correct when he says that when reading Scripture, “eschatology should be a lens and not merely a locus.”1 For example, the promise of the offspring of the woman who would triumph over the serpent (Gen 3:15) unfolds in diverse and dramatic ways across Scripture until Christ fulfills it. This eschatological aspect of Scripture is rooted in a sovereign God who is moving history along to his appointed ends—to overcome sinful rebellion, to create, sustain, and perfect covenant fellowship with his people, and to reconcile and make new all things in Christ. As a result, biblical theology attends to the unity of God’s redemptive revelation and reads the parts in light of the whole.

Second, because God’s unified revelation came over time, biblical theology gives attention to Scripture’s diversity. This diversity is marked by different biblical authors, languages, genres, cultures, epochs, covenants, and Testaments. The diversity of Scripture displays the wonder of God’s beauty, but

1 Michael S. Horton, Covenant and Eschatology: The Divine Drama (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), 5.

through Scripture’s rich diversity is an underlying unity that spans its pages from beginning to end.

Third, biblical theology reads Scripture on its own terms—that is, literately and literally its own terms, concepts, structures, and categories (e.g., creation, image, covenant, redemption, temple). It does not impose extra-biblical categories on the text but rather lets Scripture speak on its own terms and sets the agenda.

Finally, biblical theology is canonical and Christological. That is, all revelation points to and is fulfilled in Christ (Luke 24; Eph 1:10). God’s past dealings with his people serve as patterns, or types, for his future dealings with his people. Therefore, all Old Testament redemptive events, institutions, covenants, persons, and offices point to the final saving event, sacrifice, covenant, person, prophet, priest, and king. By God’s revelatory grace, the New Testament authors saw in the Lord Jesus Christ—in his person and work—the fulfillment Israel’s prophetic hopes.

In summary, biblical theology works intertextually to interpret Scripture on its own terms by tracking how it historically and redemptively unfolds from the beginning (creation in Gen 1) to end (new creation in Rev 21–22).

Systematic theology, in contrast, works from Scripture as it makes intrasystematic connections primarily in relation to its source—the Triune God—and secondarily to all things in relation to him. That is, systematic theology preserves the meaning of the terms, structures, and categories in biblical theology, but goes one step further by transforming and transposing those terms into a conceptual framework for people today. It puts all the conceptual “pieces” together to display the anatomy of their relations and proportions. Thus, it connects all reality to God and the works of God, for “from him and through him and to him are all things” (Rom 11:36).

Flowing from this point, then, systematic theology is ordered around the Word and works of God, which is why most systematic theologies display this kind of logic in their table of contents.

To spell this out, God reveals (doctrine of revelation) who God is (doctrine of God’s attributes and Triune nature) and what he has created (doctrine of creation and humanity). And, though humanity has sinned against him (doctrine of sin), God the Father has provided a gracious solution by sending God the Son, who became incarnate, who was sent in the likeness of sinful flesh to condemn sin in the flesh by becoming like us in every way yet without sin (doctrines of the person and work of Christ), for us and for our redemption (doctrine of salvation). As a result, God the Father and the Son sent God the Holy Spirit who indwells, fills, and gifts his people for service (doctrine of the Holy Spirit and the church) until the day when Christ returns to complete what he began by his life, death, resurrection, and ascension and usher in a new creation (doctrine of last things). As one can see, not only does ST give a conceptual structure to BT, but BT gives a canonical structure to ST.

A brief word on the why of ST is in order. Taking our cues from the early church, theologizing set out to protect the church against heresies, prepare new Christians for baptism and the Lord’s Supper, and disciple Christians to become mature in Christ.

Theology, therefore, was—and should be—lived. It was not for the theoretical sake of crossing theological t’s and dotting doctrinal i’s; rather, it was a matter of life and death for the sake and spread of the gospel. As a result, there are important components in systematic theology.

First, not only does systematic theology attend to the whole of Scripture and relate it to our world, but it also gives attention to Scripture’s internal relations. That is, systematic theology not only develops what Scripture teaches about the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, or deity and humanity of Christ, or faith and works, by looking at how each develops across Scripture (which is closer to biblical theology), but it goes further by asking, “What is the relation(s) between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, or deity and humanity of Christ in his (one) person, or faith and works?” As a result, the church has employed terms such as “nature,” “person,” “eternal relations of origin,” and “hypostatic union” to conceptually and faithfully summarize what Scripture teaches concerning the Trinity or the person of Christ, which has been handed down to us in the creed and confessions. Put simply, theology employs concepts and conceptual tools that provide systematic coherence to what Scripture teaches about doctrines such as God and Christ, for us and for our salvation.

Second, systematic theology gives its attention to Scripture’s proportions. That is, it distinguishes doctrines that

BY O REN R.

“Put simply, theology employs concepts and conceptual tools that provide systematic coherence to what Scripture teaches about doctrines such as God and Christ, for us and for our salvation.”

are of “first importance” such as the gospel (1 Cor 15:3) or person of Christ (1 John 4:2–3), from other doctrines of secondary or tertiary importance (Matt 23:23; 1 Cor 1:14–17). Thus, theology seeks to reflect the Bible’s own emphases and priorities in its sanctified and disciplined attention to and presentation of biblical teaching. And finally, systematic theology takes into account and is informed by historical theology, for every person approaches the text with certain (confessional) commitments.

Biblical theology grounds systematic theology, and systematic theology guards biblical theology. That is, systematic theology builds on biblical theology in its theological formulations. When systematic theologians ground their theology in the Bible, they should do so in ways that honor both what it is and how God revealed it over time. In other words, they should be doing biblical theology. The narrative structure, the story of God’s relationship with his creation—from Adam to Christ—forms the regulative principle and interpretative key for systematic theology (as it does biblical theology!). In order to reach sound biblical and theological conclusions, theologians must give equal study to all texts, giving careful attention to the literary genres and rightly interpreting each passage within its respective contexts and overall place in redemptive history and the canon. Similarly, when biblical theologians draw theological conclusions from Scripture (which they should), they should do so respecting the complex set of philosophical, cultural, doctrinal and creedal issues that attends such conclusions. In other words, they should be doing systematic theology.

Biblical and systematic theology are not foes, but friends, for they are interdependent activities in the integrated task of knowing and living before God in his world. Biblical theology seeks to interpret the diverse canonical forms on their own terms, while

systematic theology seeks to both preserve those canonical forms and transform them into a coherent, conceptual framework for today. In the end, the fixed redemptive-historical framework of Scripture (biblical theology) gives rise to a theological vision for all of life (systematic theology). As pilgrims on our way home, may we give attention to both biblical and systematic theology in pursuit of knowing God, for “this is eternal life, that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent” (John 17:3).

Boyce College fortifies students in a commitment to a Christian worldview, surrounds them with Christ-like faculty, and fosters a student life experience that instills a culture of discipleship. All so they are sent out for maximum faithfulness to Christ in every area of life. Take the first step towards fulfilling God’s call for maximum faithfulness at BOYCECOLLEGE.COM

by Jonathan T. Pennington

If our reading of Scripture does not lead us to love God and love our neighbor, then we have not truly understood it.

Augustine made this claim over 1,500 years ago, and it still speaks with piercing relevance.1 In one of his sermons, he compares the Scriptures to a road that leads to our true home. If we study the map endlessly but never start walking, we have missed the point. For Augustine, the goal was always clear: Our engagement with the Bible must move us toward love, for that is the very life of God in us. This is not a minor point—it strikes at the heart of what the Bible is for. We live in a time when Christians have more access to biblical tools than ever before. With a few clicks, we can consult

1 Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, trans. D. W. Robertson Jr. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1997), 27.

multiple translations, read centuries of commentary, and parse Greek verbs with digital precision. All of this can be a gift, but it can also subtly distort our aim. We begin to think of “application” as a secondary step, something that comes after the “real work” of exegesis. Transformation becomes an optional add-on, as if God’s Word were given primarily for information rather than for life.

But Scripture will not let us make that separation. From beginning to end, the Bible presents itself not as a static record of God’s past words but as His living speech to His people. It addresses us. It calls us. It comforts and confronts us. Reading is never merely an act of observation; it is an act of following. To read is to take up our cross again and again, to submit ourselves to the living God who speaks, and to be reshaped into the likeness of His Son.

Paul’s words to Timothy are as direct as they are profound: “All Scripture is God-breathed and

profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, so that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work” (2 Tim 3:16–17). Notice the movement here: Scripture comes from God, it works on us through multiple channels, and it produces a certain kind of life. The end goal is not simply that we would know more, but that we would be more, that we would become complete, mature, and ready to live faithfully in every circumstance.

This truth is not unique to Paul’s pastoral letters. The Psalms open with this same vision. Psalm 1 paints the portrait of the blessed person who delights in the law of the Lord and meditates on it day and night. The result is not merely an expanded storehouse of theological facts but a deeply rooted life—stable in trials, fruitful in season, and enduring through drought. The image is of a tree planted by streams of water, its life continually renewed by God’s truth.

James picks up this theme with equal force. He warns us not to be hearers of the Word only, deceiving ourselves. The Word is like a mirror, revealing who we are. But if we walk away unchanged, the mirror has not failed—we have. To truly hear is to respond, to let the implanted Word take root and bear fruit in obedience.

The early church instinctively read the Scriptures this way. They saw them as God’s living voice to His people, intended to heal, train, and transform. Pastors like John Chrysostom did not simply explain the meaning of the text; they pressed their hearers to act on it, to embody its truth in their daily lives. Scripture, they believed, was meant to move from the page to the heart and then out into the world.

If the goal of Scripture is transformation into Christlikeness, then how we come to the text matters just as much as what we take from it. Transformation is not a mechanical process that happens automatically

whenever words are read. It requires a posture, a way of approaching the Bible that is humble, prayerful, and ready to be reshaped.

The great teachers of the church have always warned that knowledge without virtue is dangerous. Gregory the Great observed that interpretation which fails to produce holy living is “not worthy of God.”2

In other words, if our study of Scripture leaves our character untouched, we are not reading it as God intends. Theological precision without Christlike humility is not merely incomplete; it is a distortion.

A true posture of discipleship is one that comes to the Bible expecting to be confronted and changed. It is an openness to hear God’s voice even when His words challenge our assumptions, unsettle our comfort, or call us to repent. It is the recognition that we are not masters of the text but servants before it, kneeling to receive what God gives.

Imagine a believer reading Jesus’s words in Matthew 11: “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” In an academic mode, this might lead to a word study on “rest” or a crossreference to Old Testament Sabbath themes—both valuable exercises. But in a posture of openness, those same words are heard as an invitation from the living Christ to lay down our burdens now. They become a doorway into prayer, confession, and renewed trust.

This is the difference between reading as an observer and reading as a disciple. The former seeks mastery over the text; the latter seeks to be mastered by it. Only the second leads to the kind of transformation the Scriptures are meant to bring.

It is possible to study the Bible deeply, to master its languages, to map its theology—and yet to miss its purpose entirely. Knowledge alone is not the goal.

2 Gregory the Great, Pastoral Care, trans. Henry Davis, Ancient Christian Writers 11 (New York: Newman Press, 1950), 74.

If the truth we learn does not take root in our lives as wisdom, then it remains incomplete.

Wisdom is more than the accumulation of facts; it is truth embodied in faithful living. It is the ability to navigate the complexity of life in obedience to God, to act in ways that reflect His character and purposes. In biblical terms, wisdom is inseparable from righteousness. It is the fruit of knowing God and walking in His ways.

Paul models this movement from knowledge to wisdom at the hinge between Romans 11 and 12. After plumbing the depths of God’s saving purposes—Jew and Gentile united in Christ, God’s mercy revealed through inscrutable providence—Paul does not end with a chart or a conclusion. He ends in worship: “Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!” (Rom 11:33).

And from that place of awe, he moves immediately to a call for transformed living: “I appeal to you therefore, brothers, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice… . Do not be conformed to this world but be transformed by the renewal of your mind” (Rom 12:1–2). Theology leads to doxology, and doxology leads to obedience.

This is the journey of reading Scripture as discipleship: from study to worship to offering ourselves to God in renewed, wise living. The Bible is not content to fill our minds; it aims to form our hearts, shape our loves, and direct our steps in the path of Christ.

If Scripture is God’s Word to His people, then it speaks a unified message. From Genesis to Revelation, the Bible tells a single, coherent story—the story of God redeeming the world in Jesus Christ. That message does not shift with the times, and it is not subject to our personal preferences. Yet this one truth, when it is

lived out, takes on a rich diversity of expressions in the lives of God’s people.

This is the reality of what can be called “bounded pluriformity.” The “bounded” part matters: The truth of Scripture is not infinitely elastic. God has entrusted His people with clear boundaries—what Jude calls “the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3) These boundaries are not arbitrary; they are marked out by the creeds, confessions, and statements of faith that the church has produced, the guardrails that keep us in the path of the gospel. Within those bounds, however, the life of faith can take many faithful shapes.

Take the parable of the Good Samaritan. The meaning is unmistakable: love your neighbor without limit, even across barriers of culture, religion, or social standing. Yet the way that truth works itself out will look different in different settings. For a church in a suburban American neighborhood, it may mean opening its homes to refugee families. For a small congregation in rural Africa, it might involve sharing scarce resources with a struggling church in a neighboring village. For a Christian working in a secular corporate office, it could mean extending patience and kindness to a colleague who has been openly hostile to the faith.

The unity of truth and the diversity of application are not in tension; they are part of the beauty of God’s Word. The same gospel that formed the early church in Jerusalem also took root in Antioch, Philippi, and Rome—each with its own culture, struggles, and opportunities for obedience. What bound them together was not identical practice in every detail but a shared allegiance to Christ and fidelity to the apostolic gospel.

Reading Scripture with this in mind keeps us from two opposite errors. On one hand, it guards against a rigid uniformity that demands every believer’s obedience look exactly the same in every context. On the other hand, it protects us from an