16 minute read

Recreation Area

Public transportation to popular trailheads will reduce traffic congestion and emissions while making the Wasatch more accessible to all. Ski resorts want transit systems that work best for them, not for the entire canyon-user community.

Advertisement

Development up Grizzly Gulch, situated at the top of Little Cottonwood Canyon in the headwaters of the valley’s water supply, would tarnish the natural landscape and encroach on visitors’ access to a true wilderness experience.

The proposed idea to connect ski resorts in Big and Little Cottonwood Canyons is a profit-driven objective to attract greater tourism and initiate further development. Ski interconnect fails to keep the best interests of wildlife, traffic, and watershed protection in mind.

Little Cottonwood Canyon’s scenic Mt. Wolverine, known for its hiking and incredible ski lines, faces the danger of unsightly and disruptive development at its summit without comprehensive legislation to keep our watershed and wild public lands protected from unnecessary infrastructure.

The incredibly beautiful White Pine area in Little Cottonwood Canyon contains Wilderness quality lands that are on par with already designated areas of the Lone Peak Wilderness, and yet this land is not included as proposed Wilderness designation.

Sign Our Petition Today

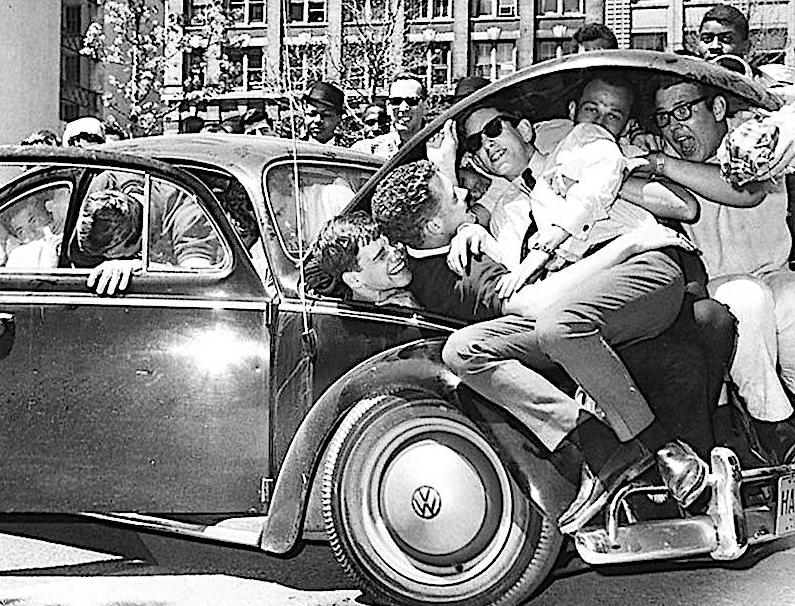

Transportation Perspectives From Our History

This is a saga that has been wearing on for decades. In the 70’s part of Snowbird’s original vision had a gondola from the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon going all the way up to Snowbird. In the 80’s, Governor Norm Bangerter had a report commissioned on interconnecting the ski resorts in the Central Wasatch, with mentions of how it would attract the Winter Olympics to the Cottonwood Canyons. Then came decades of piecemeal expansions and lift proposals by resorts to try and do it as a series of one offs. One could easily fill an old mining shaft with volumes of documents and maps along with efforts to industrialize our national forest and watershed. Some of these relics have moved with SOC for decades, many we’ve handed over to special collections at the University of Utah to deal with, while others provide structural support for Alexis Kelner’s living room.

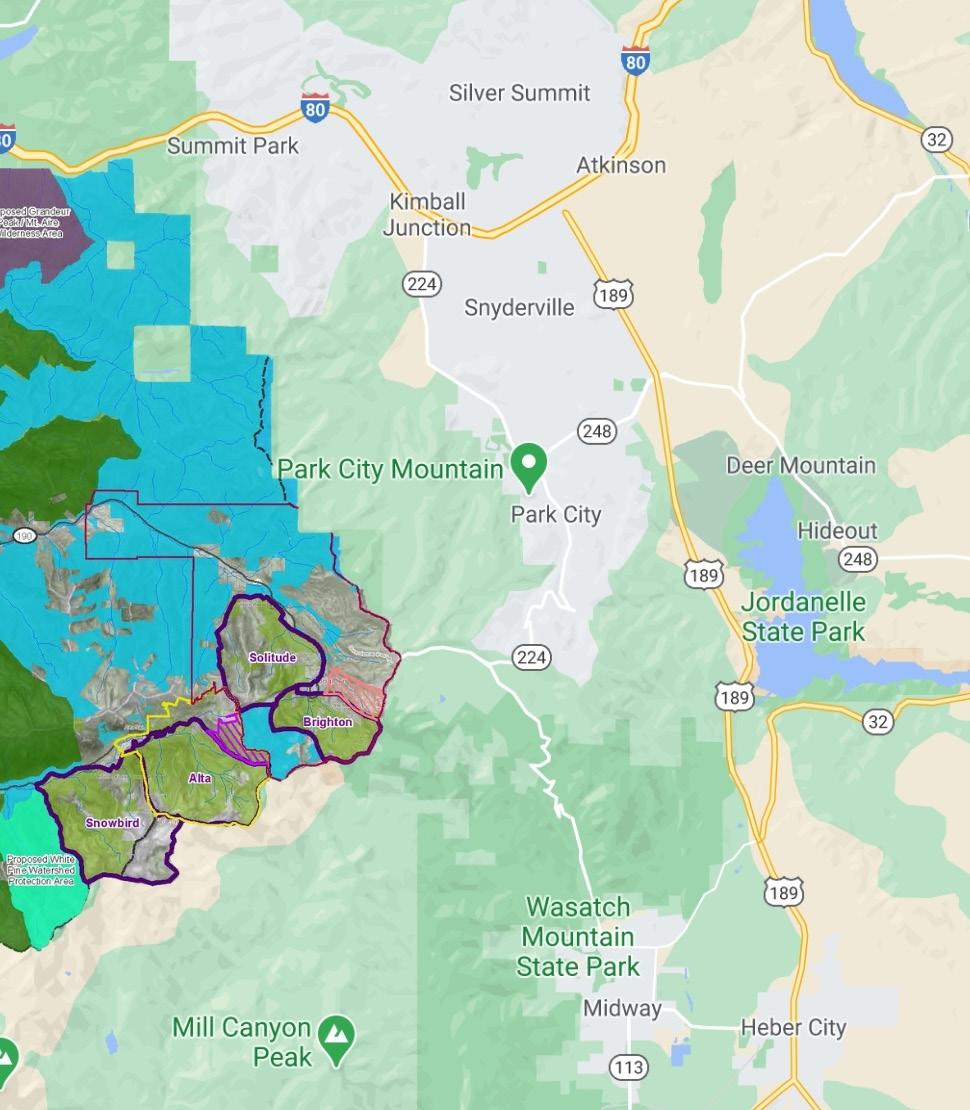

But in 2010, something a little different happened. There were two pieces of legislation before the US Congress. One was created in collaboration between conservation and commercial interests, the Wasatch Wilderness and Watershed Protection Act. The other bill, crafted in secret and facilitating development of areas many had agreed needed protection, would have built SkiLink — a lift between the Talisker’s Canyons resort and Solitude. It was the conflict of these two bills, establishing two sides, that created an opening, establishing the field for the Mountain Accord to play out.

This background is helpful because in the era of revisionist history, some will say that Mountain Accord was all about transportation and it failed because it didn’t come up with a solution. I say it failed because of Trump, and Utah’s emboldened stance after he destroyed our National Monuments, pure political brute force. That said, transportation, conservation, recreation and the economy were the agreed to pillars of the accord laid out quite plainly in the text of the agreement:

Photo Credit— Katherine and Michael Koniuch; Instagram: @katexplores

1.7. Specifically, the signers of the Accord seek:

• A natural ecosystem that is conserved, protected and restored such that it is healthy, functional, and resilient for current and future generations. • A recreation system that provides a range of settings and accommodates current and increasing demand by encouraging high levels of use at thoughtfully designed locations (nodes) with convenient access, while protecting solitude, nature, and other backcountry values. • A sustainable, safe, efficient, multi-modal transportation system that provides year-round choices to residents, visitors and employees; connects to the overall regional network; serves a diversity of commercial and dispersed recreation uses; is integrated within the fabric of community values and lifestyle choices; supports land-use objectives; and is compatible with the unique environmental characteristics of the Central Wasatch. • Broadly shared economic prosperity that enhances quality of life and preserves natural and scenic resources and infrastructure that is attractive, sustainable, and provides opportunity for visitors and residents.

UDOT’s purpose is reflected in one primary objective for S.R. 210 (road going up LCC): to substantially improve safety, reliability, and mobility on S.R. 210 from Fort Union Boulevard through the town of Alta for all users on S.R. 210.

A quick audit in the action words between the Mountain Accord and UDOT’s EIS demonstrates the state has no interest in partnering to realize the vision of our community, but further, they are hostile to that vision. They are making decisions that affect all seasons of use and the environment, but only considering 3 or 4 months of the year (Dec - Mar). Some sleight of hand is happening with the word “all”. These are fatal flaws that will not only be carried through the process, but will wreak havoc on our communities and canyons for generations to come, unless of course you have an endowment to pay to play and build your own personal water filtration system.

The following pages are intended to help understand the pros, cons, and impacts that likely won’t be explored by UDOT, primarily because their jurisdiction and vision for the canyons begins and ends on pavement, severing a watershed, that watershed managers have astutely accused them of ignoring and causing irreparable harm.

Canyon Capacity

The current system for managing visitor capacity is by parking. It is clear this is a flawed model, in part, thanks to UDOT, who won’t enforce roadside parking. And allowing overflow parking miles down the canyon highways from the parking areas, designed to accommodate only a finite number of cars. The USFS has abandoned trying to enforce its forest plan and adhere to parking, furthermore, allowing Alta to expand parking areas in the iconic Albion Basin because we flock to see rows of cars in the new Albion dust bowl, not wildflowers, right?

Better late than never, local governments have heeded the calls from the public and are in the process of looking at canyon capacity through a visitor management study. That said, the USFS has indicated it isn’t interested in those findings. National Parks however, have found these to be useful studies, so as we go forward, we may need to start looking for a new land management agency. One that can manage the Wasatch for its wild and watershed characteristics, rather than just kowtowing to resort and monied interests. This could be accomplished through legislation.

In 2019, the Wasatch Mountains, which act as the watershed for the million plus residents living nearby, saw nearly six million user visits. That’s roughly equivalent to the combined visitation numbers for all five of Utah’s National Parks, but in an area one fifth the size of those iconic parks. The simple truth here is that we cannot manage the existing numbers of visitors so looking at high capacity transit modes like trains or gondolas is patently insane. It is the local customers paying for the water coming from these canyons that footed the bill to steward these resources (clean and build restrooms), not the USFS and State of Utah. Even though they continue to promote and increase visitation pressures, more money goes to marketing campaigns than resource management; “It’s all yours” & “Life Elevated”. Seems equitable that the visitor also contributes to stewarding the resource they’re enjoying.

Is this the future of the Wasatch Mountains?

All of the UDOT options (bus, gondola, & rail) would require the construction of thousands of parking stalls near the mouths of the Big and Little Cottonwood Canyon. UDOT thinks about moving cars, not people, they’ve failed to incorporate into their scope delivering people to the canyon entrances without a car. These parking garages will just shift the traffic jams currently being held in the canyons further into valley neighborhoods as they queue up to navigate the maze of a parking garage at already busy areas.

Not only will these garages need land that isn’t really available, building parking is expensive too. We’ve heard the new garage built at the mouth of the canyon cost about $30,000 PER STALL! That’s a cost we will all bear. Better transit to and from the canyon mouths would be a much wiser public investment, that will protect land and water, clean our air, and improve walkability around these already congested areas. Simply running buses on roads that are already in existence would negate the need for additional parking impacts.

We must think about the decisions we are making as a year-round, 365 day, and 8,760 hour solution.

Development Pressures

Delivering more people to the Wasatch will surely drive more development pressures. For the past 15 or so years, Salt Lake County has done a public option survey on our watersheds. It finds, pretty consistently, that only 7% of people want more development in our watersheds, while 41% say they want “about the same” amount of development and the majority, 52% say they want less than already exists today!

You may be shocked to learn that there is already more development than exists today in the Central Wasatch. Resorts and other developers amass development authorizations that have yet to be realized to inflate their value for potential sellers. For example, Snowbird has only built about 50% of what they are authorized to do —so effectively you could see another Cliff Lodge and another Iron Blossom come to the canyon. We at Save Our Canyons fervently believe that the interest in high capacity has everything to do with realizing this (and possibly more) development in the headwaters of our canyons, and laying the foundation for future Olympic venues in the Cottonwoods. It is a classic positive feedback loop, and a damning cycle that needs to be broken. More people, more cost, more development and infrastructure, repeat (without even rinsing).

Recreation Displacement

The greatest burden to help the ski areas get more visitation by these transportation modes will be borne by the people just trying to experience the beauty of the Wasatch away from resorts. The wildly popular Little Cottonwood Quarry Trail and beautiful creek will be replaced by railroad tracks and gondola pylons. No more morning or afternoon rides and hikes along the creek looking at birds. Popular climbing areas and boulder problems will enjoy that same fate, so that resort skiers have better access. Tanner’s Campground will be replaced by angle stations and the serene sound of the rushing

Much of this could be avoided by just running more buses and removing cars from the roadway that is already in existence. Or why not replace the roadway with rail tracks, there’s already a disturbed corridor. Transportation projects just aren’t as great if you can’t chase, The Lorax through the forest with dozers and cranes and other implements of destruction. Just as the desert tortoise in the Red Cliffs NCA - UDOT’s other myopic and damaging transportation initiative.

Watershed Impacts

Any project that isn’t using existing paved areas is going to have destructive impacts on the hydrology, thereby, our watersheds. A 2012 USFS study found that Little Cottonwood Canyon was an “Impared Watershed”. There are stretches of stream where aquatic life is unable to survive. The report that accompanies the finding cited,

“The main limiting factor for improvement is the impaired water quality (zinc) in Little Cottonwood Creek because it limits the aquatic productivity of the stream channel. Several culverts create fish barriers. New unauthorized hiking and mountain bike trails located near Little Cotonwood Creek are causing erosion and sedimentation of the stream.” So naturally, transportation managers are looking to add cuts to the thousands of cuts already degrading our waterways, thereby diminishing your water quality. Increased turbidity caused by erosion and alterations in hydrology, further impede aquatic life, decrease the amount of oxygen in the water, increase temperatures and would likely increase the likelihood of algal blooms infecting these waterways.

Photo Credit — Howie Garber; Instagram @howiegarberphotography

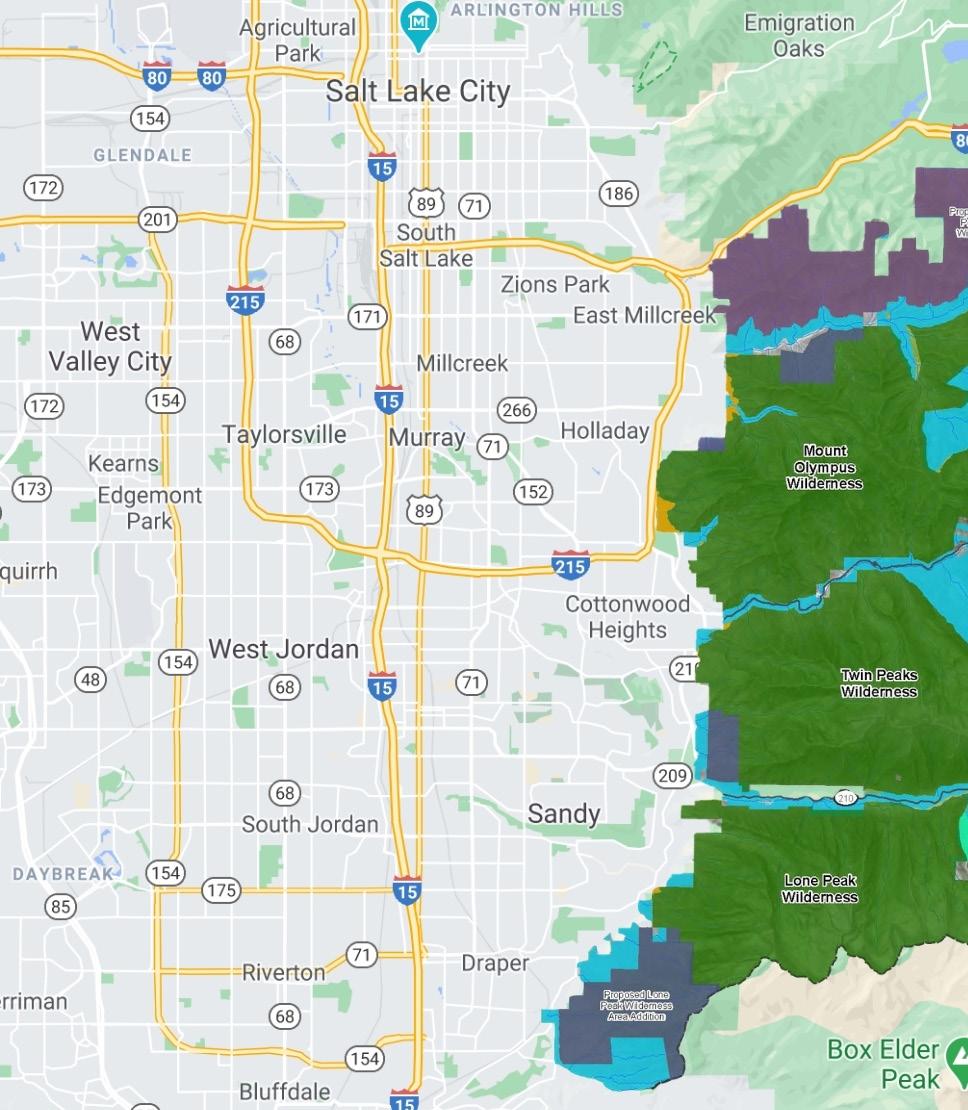

Big Cottonwood Canyon

They’re looking to allocate up to $1 billion towards Little Cottonwood Canyon (LCC) transportation, but not even considering Big Cottonwood Canyon (BCC). This means that the UDOT EIS is not addressing the landscape and visitor scope comprehensively. The parking proposed is only looking at accommodating LCC visitors, not BCC visitation, thereby programming a massive deficit and creating systemwide failures, thus failing visitors, communities and our canyons.

Wildlife Impediments

The roadways, trails and resorts already create impediments to wildlife movement. Adding new infrastructure, roads or guideways will further create barriers to wildlife, terrestrial, aquatic and avian alike. This will further contribute to the rapid and horrible extirpation of species whom we share the Wasatch with, making way for non-native species to fill their niche — fundamentally altering the wildness of the Wasatch.

We already have a lot of impacts on the species we share the Wasatch with and there are some studies going on in this very geography to better understand the impact. New modes, new corridors and the new recreational amenities they will fuel, will undoubtedly have a compounding (not necessarily linear) impact on wildlife.

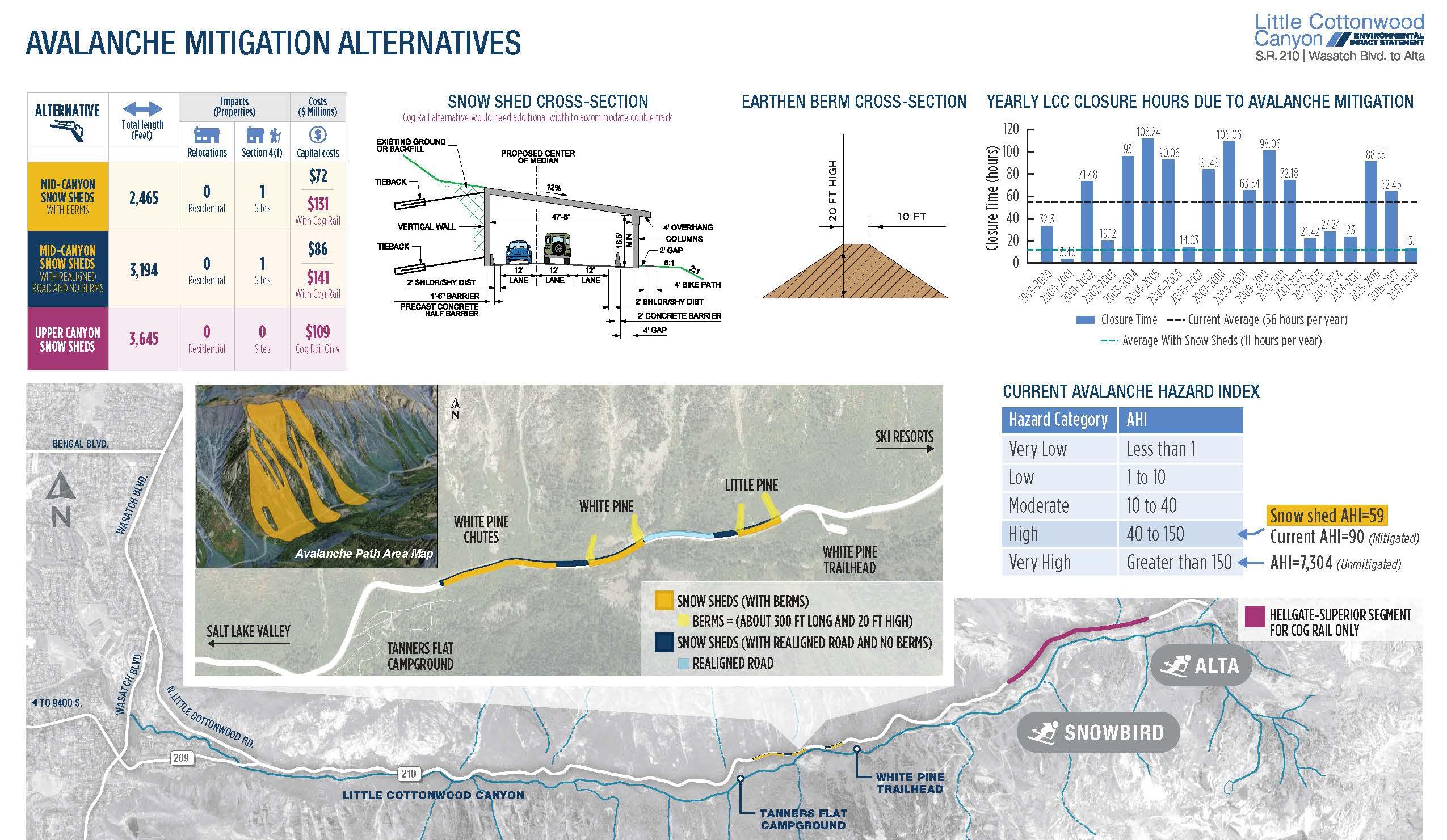

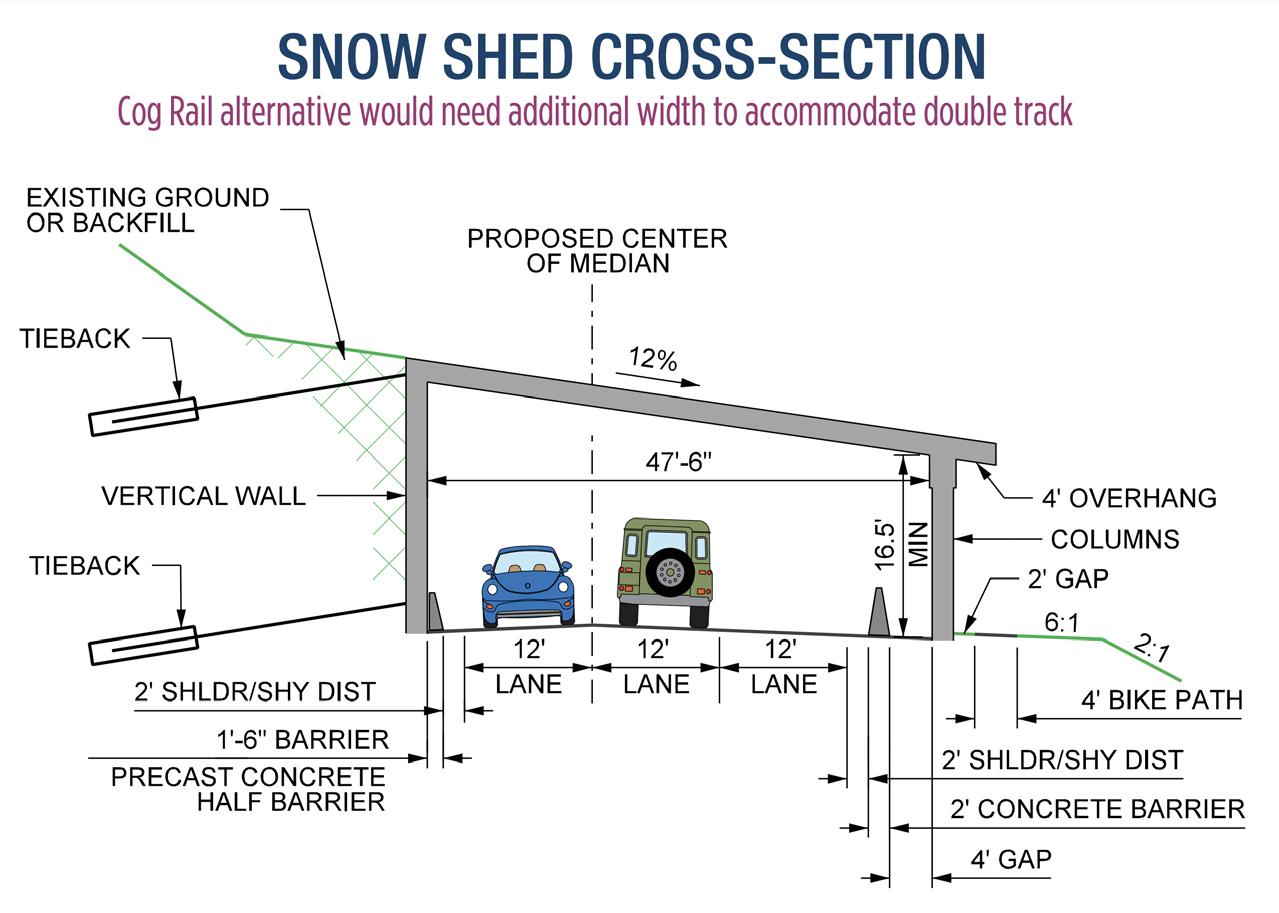

UDOT’s Little Cottonwood Canyon Environmental Impact Statement — Alternative Factsheets Avalanche Mitigation

The snowshed would run up the North wall of LCC about 300 linear feet

Avalanche Mitigation

According to UDOT’s EIS, avalanches cause 6 to 10 days of closure on average, per year. This is a primary consideration for what mode and associated mitigating measure will be installed. Another way of putting this, for a hand full of days, we are permanently going to change the canyon forever. It is akin to damming a river or blowing up a rapid, to ensure safer passage at higher levels.

Unsightly avalanche sheds will likely accompany every mode being considered because reliability has become one of the highest values to commercial interest. Both the gondola and the rail proposals include them because both require at least 70% of the vehicles to continue to use the road way. We argue there will likely still be 100% of the cars, because what is actually happening is a 30% increase (at minimum) in visitation to these canyons, rather than a 30% reduction in cars.

Service Roads

Every tram, lift and gondola has service roads, both for construction, but also for evacuations. Given this will be the longest gondola likely with the most towers, with a 45-minute transit time and given the rapid changes in mountain weather (particularly in the winter), it is likely that there will need to be numerous roads accessing the gondola guideway, which are currently not in existence. High canyon winds are not uncommon, and storms shutting down the gondola because of high winds are probably more of a frequency than the avalanche issues that complicate the existing roadway. Can you imagine being stuck in a gondola in the middle of Little Cottonwood Canyon during a windstorm?

Wait Times and Increased Visitation

rooms to parking, to condos and restaurants, possibly more lifts too. As we look to solve the problems of today, we need to make sure we aren’t just making it worse. Removing 30% of the cars from the road way and putting them on another mode, just makes room for 30% more cars on the roadway, which is an increase of 30% in visitation. Ski areas like Alta state they need to grow commensurate with visitation (30% more visitors = 30% more parking = 30% expansion of the resort).

Further, introducing a mode shift to a train or gondola at the busy mouths of these canyons will only make things worse. As thousands of people flock to the canyon entrances to either drive or get on a proposed gondola or train departing from the mouth will only exacerbate the problem we are living today. Snowbird’s Aerial Tram has wait times to load many times in excess of an hour, so as you are looking at the 40 min travel time for a gondola, make sure you factor in wait times as the assumption is that there won’t be wait times. At what point is waiting an hour for a 40 min gondola ride diminishing returns?

Parting Thoughts

Many of these issues are being purposely hidden or just ignored from the conversation. We aren’t bringing them up to be argumentative, rather to be thoughtful and methodical and to truly understand what we are embarking on with these very impactful modes. It might be easy to disregard any one of these issues in isolation, however, ignoring the combination of these and the ripple effects they will have on both visitor experience and the impact to the Wasatch is just irresponsible. This list isn’t exhaustive, it can’t be.

We’ve articulated several visions for the Wasatch. Some are based in history, some are derived through compromise and community engagement, some based around policy -- all driven by science, vision and passion. I suppose one of the most damaging things about UDOT’s Little Cottonwood EIS is that they aren’t being honest with our community, or themselves, about what their vision is for the Wasatch. The Central Wasatch Commission is at least being more thorough in that regard… the short coming there is, just as we have been fought and vilified by the State, so have they. The concerning thing about the CWC’s process, is that the land use changes they acknowledge they will need (locally and federally), are also being fought by the State.

So until the State of Utah, is honest with itself, and with all of us, it will be impossible to fully understand what their vision for the Wasatch is. We are left wondering if their plan or their lack of a plan is more frightening. The best weapon to fight this is to unify behind a protective plan because there are only two fights: fighting to protect or fighting to develop. Your tax deductible donation enables us to continue protecting the beauty and wildness of the Wasatch Mountains. Becoming a member by donating online or by mailing in a check to:

3690 E Fort Union Blvd STE 101 Cottonwood Heights, UT 84121.

Join

Save Our Canyons relies critically on the support of individual members and local businesses. Join today for only $35: https://saveourcanyons.org/join!

Renew

Renew your one-year membership today for only $35, and keep doing your part for the Wasatch: https://saveourcanyons.org/renew.

Give Monthly

Become a monthly member for as low as $5 a month: https://saveourcanyons.org/give-monthly.

Membership Benefits

• Connection to a community passionate about conservation • Discount on ALL Save Our Canyons event tickets • Direct access to our brightest conservation leaders • Ability to serve on a Save Our Canyons advisory committee • An exclusive Save Our Canyons membership event • Quarterly newsletters delivered to your door or via email (your preference) • Action Alert emails that focus on direct actions to protect the Wasatch

Other Ways To Donate

There are multiple ways you can support or donate to Save Our Canyons! Donate stocks, bonds, mutual funds, IRA accounts, real estate, life insurance, business interests, and bequests through your will or trust! If you’re interested in leaving a legacy of support for the continued preservation of this amazing range and the communities it supports please contact Sarah Sleater at sarah@saveourcanyons.org or 801-363-7283.