5 minute read

I. Introduction

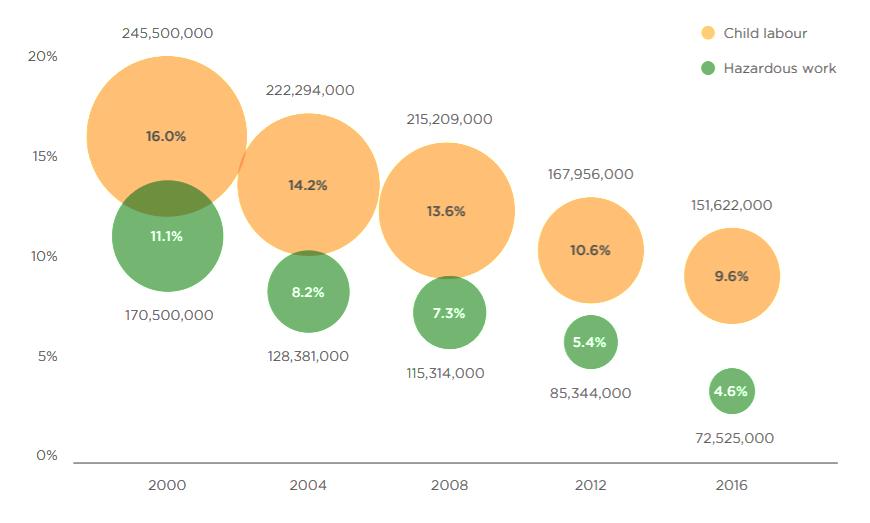

The good news is that the estimated prevalence of child labour dropped by almost 40% to the begin of the new millennium. Between 2000 and 2016, according to the International Labour Organization (International Labour Office, 2017a) estimates, the world witnessed a net reduction of 94 million children exposed to child labour, from an estimated 246 million to 152 million children.

Figure 2: Children’s Involvement in Child Labour and Hazardous Work, Percentage and Absolute Number of Children, 5-17 Age Range, 2000-2016

Advertisement

Note: Bubbles are proportionate to the absolute number of children in child labour and hazardous work. Source: Global estimates of child labour: Results and trends, 2012-2016, (International Labour Office, 2017a), URL

The bad news is that the trend of decreasing child labour will, however, likely be reversed due to global economic contraction precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. One study performed in Tamil Nadu exemplifies how the financial strains created by COVID-19 are driving children to work: released by the Campaign Against Child Labour (CACL), a survey conducted in 24 districts by child rights specialists R. Vidyasagar and K. Shyamalanachiar, shows that the number of children in vulnerable communities (such as SC/ST) increased from 231 to 650 compared to pre-COVID-19 levels (“Child Labour on the Rise,” 2021).

Indeed, an additional 86 million children are estimated to have fallen into poverty in 2020 as their parents lost their source of income, forcing the children to interrupt their education and some to work (United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF], 2020). According to World Bank reporting, the number of people living in extreme poverty (living on less than $1.9 per day) was steadily decreasing, but jumped by 119 million in 2020 (see Figure 3). From the

baseline of 2019,

“the estimated COVID-19-induced poor is set to rise to between 143 and 163 million” (Lakner et al., 2021) in 2021.

Figure 3: Nowcast of Extreme Poverty, 2015-2021

Source: Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty, (Lakner et al., 2021), URL

In a bid to step up efforts that reduce forced labour and child labour, the year 2021 has been declared by the UN General Assembly as the Year for the Elimination of Child Labour. The underlying unanimous United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) resolution called on member states to “take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms” (United Nations [UN], 2015a, p. 20).

As for the EU, the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen (2019), has stated that EU trade policy should have ‘zero-tolerance’ for child labour. Prior to that pronouncement, the Council Conclusions on Child Labour (Foreign Affairs Council, 2016) had noted that the worst forms of child labour should have been eliminated by 2016 according to the Roadmap (The Hague Global Child Labour Conference, 2010) adopted in The Hague in 2010 and reaffirmed in the Brasília Declaration on Child Labour (III Global Conference on Child Labour, 2013) adopted in 2013. Furthermore, the Council had encouraged “the High Representative and the Commission to explore how the EU can step up its contribution to the realisation of SDG target 8.7 which calls for measures to [...] secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms”

(Foreign Affairs Council, 2016, p. 4). 2 Lastly, the Council encouraged “the Commission, in line with its ‘Trade for All: Towards a more responsible trade and investment policy’ strategy, to continue exploring ways to use more effectively the trade instruments of the European Union, including the Generalised Scheme of Preferences and Free Trade Agreements to combat child labour” (Foreign Affairs Council, 2016, p. 4).

The European Parliament resolution of 7 October 2020 on the implementation of the common commercial policy also treated the issue of child labour, notably in sections 54 and 55. Section 54 “calls on the Commission to monitor the progress made with respect to the implementation of […] ILO conventions, and to set up without delay the interparliamentary committee as agreed under the EVFTA, paying special attention to the prohibition of child labour” (European Parliament, 2020b). Further, Section 55 “Recalls the need for an effective action plan to implement the goal of zero tolerance of child labour in FTAs, by building a strong partnership with NGOs and national authorities in order to develop strong social and economic alternatives for families and workers, in coherence with actions taken under the EU development policy.” Section 63 goes on to discuss the newly created role of the Chief Trade Enforcement Officer (CTEO), chiefly “to monitor and improve compliance with the EU’s trade agreements.” The section furthermore:

notes that rules under EU trade agreements should be properly enforced in order to ensure their effectiveness and address market distortions; underlines the need for this newly created post to focus on implementation and enforcement of our trade agreements, as well as on breaches of market access and trade and sustainable development commitments; is of the opinion that the CTEO should not only monitor and enforce environmental and labour protection obligations under the EU trade agreements with third countries, but also focus on implementation of all chapters of trade agreements in order to guarantee that these are used to their full potential (European Parliament, 2020b).

The extent to which child labour may simply be “eliminated” is, however, a matter of contention. For one, an act of survival ought not be stigmatised. Two, target-setting should be underpinned by a meaningful capacitation of beneficiaries. Stating that they could “no longer continue blindly with the well-intended but unrealistic goal of eliminating child labour by 2025” (“Open Letter: Change Course,” 2021) a group of 101 academics recently called for the issue to be viewed rather through the lens of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC). The authors further cautioned that “eliminating child labour as a resolution without addressing fundamental structural problems of poverty and inequality will not be successful,” and that only removing children “from work is no help if this drives them deeper into the famine and broken lives that the work was undertaken to mitigate” (“Open Letter: Change Course”, 2021). Instead of a blanket prohibition of child work, the aim, instead, should be to reduce truly harmful types of work, while, however, protecting the utility of “beneficial work.” In response, the ILO highlights the fact that non-hazardous child labour is also harmful; the empirical evidence showing that the practice is harmful to children's education and future prospects (B. Smith, personal communication, May 20,

2 Indicator 8.7.1 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals is the “Proportion of children engaged in economic activity (%) – Annual.”