5 minute read

STILL ON THE DIME

Former deputy chief public defender accused of sexual assault still works for New Mexico’s public defender department

BY BELLA DAVIS bella@sfreporter.com

Advertisement

Jocelyn Garrison’s career as a New Mexico public defender began to fray when she accused her boss in the Clovis office of choking her, hitting her genitals and telling her she “liked it like that.”

It was 2017, and after more than a year of the Law Offices of the Public Defender brass allegedly retaliating against her for reporting the alleged assault, she resigned and later sued the agency and her former boss, Chandler Blair, the agency’s erstwhile second-in-command.

In January, the case settled for $750,000. Among the terms: Garrison can never again work as a public defender, either on staff or on contract.

Meanwhile, Blair has continued to cash checks to represent the state’s indigent defendants—to the tune of nearly as much as the state paid Garrison in the settlement— even though he quietly resigned from his post as deputy chief public defender on July 26, 2018, about a year and a half after the alleged assault.

The very next day, he inked a contract with the agency, signed by Chief Public Defender Bennett Baur, that opened the door for him to help buttress the state’s beleaguered public defender corps with a top-end price tag of $550,000. The contract has been renewed every year since, and Blair has raked in about $730,000 to work on 1,268 cases for the department.

Albuquerque-based civil rights lawyer Laura Schauer Ives, who represented Garrison in the civil case, says the decision to bring Blair back on as a contractor is “not surprising but deeply disappointing.”

“We, the taxpayers, are paying him and that’s a slap in the face to every woman who comes forward and in particular to Ms. Garrison,” Schauer Ives tells SFR. “That men in positions of authority continue to want to protect men who have been credibly accused of, in this instance, not just sexual harrassment but a sexual assault in the workplace, is disheartening and discouraging.”

Blair did not respond to multiple requests for an interview with SFR, and Baur, through a spokeswoman, refused to be interviewed.

The public defender agency did, however, provide the contours of its ongoing working relationship with Blair through a response to a request under the New Mexico Inspection of Public Records Act and emailed responses from agency spokeswoman Maggie Shepard.

Blair accepted a contract in July 2018 after a couple other attorneys in Cibola County terminated their contracts on short notice, Shepard says. A few months later, in November, he participated in the department’s regularly-scheduled request-for-proposals process, during which he received a contract for Cibola and Bernalillo counties for all types of cases and statewide for first-degree murder cases.

Of the 112 attorneys the agency has on contract, Blair is one of 36 authorized to represent clients in complex and murder cases, Shepard tells SFR.

He does public defense work primarily in Cibola County, in addition to work done separately out of his Albuquerque-based, private firm. A search of New Mexico court records shows Blair acting as a public defender for people charged with first-degree murder, aggravated burglary and trafficking controlled substances, among other crimes.

Another example of a client Blair is representing, this one through his private practice: A Cibola County man accused of aggravated stalking and violating a restraining order prohibiting domestic violence in October who’s set to go to trial next year.

Blair’s public defender contract has been renewed each year since 2018, per the approval of Baur, the agency chief financial officer and the director of contract counsel legal services. The first amendment to Blair’s contract, made in May 2019, increased his workload and possible compensation, up from a maximum of about $107,000 to $237,000.

Since July 27, 2018, the agency has paid him $732,990, according to Shepard. (As a contractor, he’s responsible for his own business costs, including office space, insurance and support staff.)

Baur, after not responding to multiple telephone messages, said in an emailed statement through Shepard: “It is common for attorneys to resign or retire from LOPD and take contracts in private practice. Mr. Blair, who resigned from LOPD, is a very experienced attorney who was willing to take cases in areas where we were—and are—in need of contract attorneys.”

Baur did not address the concerns raised by Schauer Ives about Blair receiving contract work after leaving the department amid sexual assault allegations.

Garrison was working as a managing attorney at the public defender’s office in Clovis when Blair allegedly assaulted her.

In her lawsuit, Garrison claimed Blair sexually harassed her and other female staff members and had a sexual relationship with a paralegal that made the office dysfunctional. Garrison requested to be transferred to the Las Cruces office but, in February 2017, before the transfer went through, Blair allegedly assaulted her.

An independent investigator reported to the agency later that year that Garrison was “very credible in her testimony,” and the Human Resources Department recommended that Blair be fired.

But he was allowed to keep his job.

Garrison’s transfer to the Las Cruces office was approved a month after the alleged assault. Over the next year, she wasn’t warned when Blair would be present in the office—she sought medical treatment on at least one occasion for the stress his unexpected presence caused her—and was given the largest caseload of any attorney in the office, according to the lawsuit.

“It’s very difficult for women to come forward with anything like this and when she does so, the department betrays her and then retaliates against her for reporting it instead of doing the right thing,” Schauer Ives says.

Garrison resigned in May 2018 and sued Blair and the agency that December.

Blair, meanwhile, remained in his position as deputy chief public defender, second only to Baur, for over a year after he allegedly assaulted Garrison.

In July 2018, shortly before he resigned, the Public Defender Commission presented Blair with the “Fearless Defender” award— the first such award the commission has ever given out, Blair’s website claims.

-Laura Schauer Ives, civil rights attorney

COURTESY WWW.CHANDLERBLAIRLAW.COM

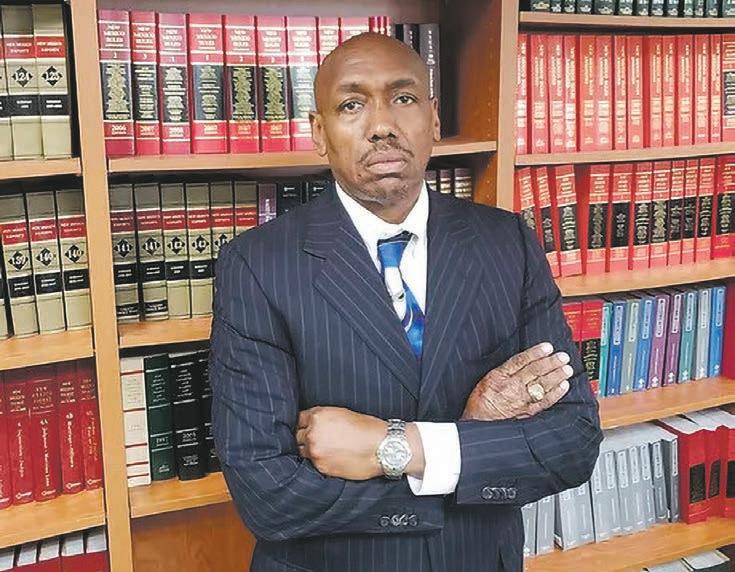

Chandler Blair, former deputy chief public defender, entered into a contract with the Law Offices of the Public Defender shortly after resigning amid sexual assault allegations.