22 minute read

The Odyssey of Luke Soules

By Steve A. Peirce

If you are ever in court at the Bexar County Courthouse or maybe even Justice of the Peace Court, you might see a lawyer, nearing 90 years old, representing a poor person in a small consumer matter. And you would notice that lawyer squinting unusually close to a monitor with the text blown up so large that you can see it from across the room. And you might think, “What a shame that this half-blind lawyer is having to work well beyond retirement age handling such small cases.” But you would be thinking wrong. That lawyer is Luther H. “Luke” Soules III, one of the most successful courtroom lawyers in Texas history. For the last two decades, he has been handling consumer cases pro bono, and he remains a formidable advocate.

I’m sitting in Luke’s office, a small one-story building just outside Loop 410. The décor is ranch style, as if Luke had acquired Ben Cartwright’s furniture and art from the set of Bonanza. Indian beadwork, a saddle, and western paintings and sculptures accompany law books (some written by Luke) and memorabilia and awards from his storied legal career. There are several courtroom artists sketches of his trials on the wall, and how many of us have those? Though he practices solo, his firm retains the name of Soules & Wallace, the “Wallace” being his longtime law partner, retired Texas Supreme Court Justice James P. Wallace. The entry to his office has a portrait of Justice Wallace, accompanied only by a portrait of another revered law partner, Luis Garcia. “Luis worked for the City Attorney’s office, and I saw him in court one day when he announced that he was retiring. Everyone liked Luis. I approached him and offered him a position,” Luke recalls.

We are waiting for a meeting with representatives from the University of Texas Law School, where Luke will discuss with them a potential establishment there and at Texas A&M Law School of a transformative new program for equal access to justice for the underserved, to be funded in part by a large donation from the foundation Luke started. While he is showing me the special equipment he uses to practice law as a blind person, he answers a cell phone call, which turns out to be an unsolicited offer to sell him home insurance. Ever the advocate, Luke informs the caller that he is a lawyer who happens to be suing that insurer for wrongfully refusing to replace a $10,000 hail-damaged roof of a pro bono client, so no thanks. The caller didn’t make the sale, but he has a story to tell. And so does Luke.

The Young Go-Getter

In my experience writing about some high achievers in the legal profession, something has occurred to me. Many of them undertook responsibility and leadership roles at an early age, and most have supportive, though not necessarily wealthy, parents. Luke Soules was one of those youngsters. He grew up in Dallas and spent his early summers helping with chores on the Soules grandparents’ farm in Goldthwaite, Mills County, Texas. He joined the Boy Scouts at age 10, became an Eagle Scout at 16, and continued to support scouting as an adult, earning a Silver Beaver Award in 1994 for his volunteerism. At 14, he started a lawn, garden, and landscaping business, towing his lawnmower on his bike and knocking on doors in the neighborhood. When Luke was 16, his father, then a sales manager for Canada Dry Bottling, put him through the company’s sales training program, and young Luke assembled product displays in grocery stores. At 18, he was dispatched to Louisiana in the summer to sell Canada Dry ginger ale to the grocers. In high school, he was in R.O.T.C., ran track, took art classes, and served as Student Council President.

The Dedicated Aggie

Luke arrived at Texas A&M University in the fall of 1957, as a young cadet in the A&M Corps of Cadets. He had followed two uncles who graduated from Texas A&M on G.I. Bills after World War II. Five years later, he emerged with two degrees, a B.A. in Economics and a B.A. in Mathematics. He was deeply involved in the MSC Student Conference on National Affairs (“SCONA”), an organization of college students from all military academies and top educational institutions who convene to discuss issues and policy proposals of national importance. Think of college students with ideas on how to run the country. In his fifth year at A&M, he served as A&M’s delegate to the similar Air Force Academy Assembly conference, and he earned his room and board that year as a dormitory supervisor in nearby Bryan at Allen Military Academy for boys. College summers were spent earning funds to pay for the next year. Luke’s dad took an executive position marketing Ranch Style Beans, and after Luke’s freshman year, Luke spent the summer selling Ranch Style Beans to grocers in Arkansas. “Ranch Style Beans are pinto beans, and no one in Arkansas ate pinto beans. So I would cold-call at the grocery store with a can of Ranch Style Beans and two plastic spoons. I would open up a can of beans, give the manager a taste with one spoon, and take a taste myself with the other spoon,” Luke recalls. It was an eye-opening (and can-opening) experience for Luke. “I met and got along with strangers of every description, all good working people,” he says.

A&M alums are a passionate and dedicated lot to their alma mater, but few as much as Luke Soules. Luke and his wife Andrea have financially supported A&M with an Endowed Chair in Global Macroeconomics Theory and Policy in 2024, scholarships to the Department of Economics, and other programs at the university such as the Century Club, the Chancellor’s Century Council, and the Texas A&M Mariachi Band. All told, his financial contributions to A&M run in the seven figures and, in light of the seismic 2025 global trade-shift activities, his Endowed Chair in Global Macroeconomics—inaugurating in 2024 the unique and transformative new program at the Economics Department—appears somewhat prescient.

Back in the Bean Business

Upon graduating from A&M in 1962, young Luke’s plans for law school gave way to a plea from Luke’s dad (Luke Soules, Jr.), who was starting a business called Luke Soules, Inc. Luke’s dad had grown up a farm boy in Mills County, was valedictorian of his high school class, and had attended a two-year program at Brantley and Draughon business college in Abilene. Through Luke Soules, Inc., he had an opportunity to represent Ranch Style Beans, the product line of Fort Worth-based Great Western Foods. “Dad needed my brother Joe and me to work for him, because he didn’t have the money to pay for employees, and the opportunity required the family to move to San Antonio,” Luke recalls. “So my brother and I went to work for dad’s company. I worked there for two years, while my brother Joe made a career with the company.” Luke Soules, Inc. did quite well, ultimately becoming part of Acosta Brokerage, the largest national food sales and marketing company. “My parents were great examples, and they were attentive despite not having a lot of resources,” he says. Luke so revered his dad, the farm boy turned entrepreneur, and his mother Merle, the farm girl turned registered nurse and homemaker, that he named his charitable foundation, the Luke and Merle Soules Family Foundation, after them. Thus far, the Foundation has donated over $7 million to various charitable, educational, and philanthropic causes.

On to Law School

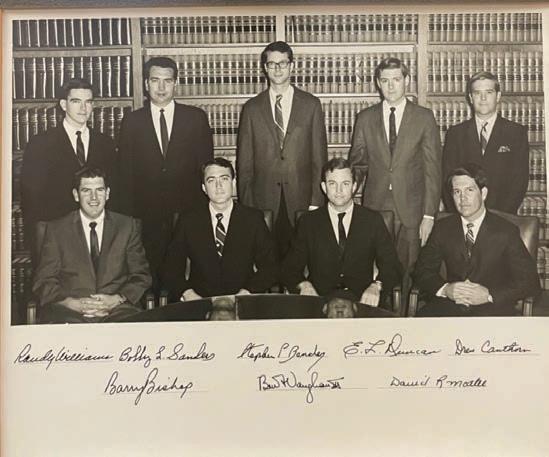

After his stint with Luke Soules, Inc., Luke started at University of Texas Law School, graduating in 1967. “I was starting a bit late, because I was almost 7 when I started first grade; and I had a fifth year at A&M and two years working for my dad,” Luke recalls. During law school, he worked as a Teaching Quizmaster, interned for Texas Senators A.R. “Babe” Schwartz and Jack B. Strong, and managed his apartment complex in exchange for his rent. He participated in moot court competitions and was awarded his first of many legal accolades to come, the UT Law School Student Bar Association Consul Award, given to “senior law students who have made outstanding contributions to the School of Law.”

The Rules Guru

Upon law school graduation, Luke was selected as the sole briefing attorney for Texas Supreme Court Chief Justice Robert Calvert for a one-year term. “No baby lawyer could possibly hope for a better beginning,” says Luke. “As a briefing attorney, I was able to participate in the reasoning of decisions and observe the court’s deliberative process.” Luke considers Justice Calvert—“a giant legal scholar”—to have been his mentor. “Justice Calvert opened a lot of doors for me,” he says. And maybe the best bar service decision Luke ever made (and there are many) was to stay connected with the Texas Supreme Court as a member and Chair of the Supreme Court Advisory Committee on trial and appellate rules. The rules advisory committee serves the Supreme Court by advising on how trial and appellate procedural rules are working and makes recommendations on changes to the rules to improve the administration of justice. He was reappointed and served under six successive Chief Justices. “I served on the rules advisory committee for thirty years, the last twenty as Chair of the committee,” says Luke. Among other things, Luke spearheaded changes to the summary judgment rules, recusal rules for Texas judges, and standards for determining discovery sanctions. And knowing the rules means knowing the cases interpreting the rules. “The Texas appellate courts issue about 900 opinions a year,” says Luke, “and I would read each one of them as soon as they were published in the advance sheets.” And if you don’t believe him, see Chip Babcock, Tribute to William V. Dorsaneo, III, 75 SMU L. Rev. 11 (2022) (“Luke would read advance sheets (I mean all of them) and send cases to his colleagues that he thought would interest them, especially Bill [Dorsaneo]”). This made Luke Soules the statewide go-to authority on the Texas rules. He shows me the volumes of Dorsaneo and Soules’ Texas Codes and Rules: Civil Litigation, a bible of case law and commentary on the Texas Rules authored by Luke and the aforementioned Professor Dorsaneo. “There are over 3,000 Texas Supreme Court cases cited alone in that book,” says Luke.

The South Texas Outdoorsman

“I decided to start my legal career in San Antonio because Chief Justice Calvert said that it had an outstanding bench and bar, and because I’m an outdoorsman. I don’t play golf or tennis, but I loved to hunt and fish and take photographs, and the San Antonio and South Texas area was perfect for that,” Luke says. He ultimately acquired the Lagos Ranch in Medina County, known for its many lakes, and became a veritable cinematic image (think Robert Mitchum) of a cigarchomping Texas rancher-trial lawyer (though these days, he’s more likely to place a chaw of tobacco between his cheek and gum). And he trained bird dogs, winning a national field trial championship with his two-year-old “derby dog,” Kismet. Later, he got into genealogy, and in typical Luke Soules fashion, it was a thorough job. He discovered that he is a direct descendent of George Soule, a Mayflower bondage passenger and Mayflower Compact signer, and his ancestors include six other Mayflower passengers. So he joined and supported Soule Kindred of America, an organization of the descendants of George Soule. He is also a member of the Sons of the American Revolution by descent from Moses Soule and a member of the Sons of the Republic of Texas.

The Epic Court Battles, and a Bleak Prophecy

Luke began his private-practice job search by sending letters and resumes to law firms, with many no-callbacks. One such no-callback was the venerable law firm of Matthews, Nowlin, Macfarlane, & Barrett (later Matthews & Branscomb). Well, Luke just showed up at the firm, informed the hiring partner that he had not received a response to his letter, and soon was offered and took his first law firm job there. Not unlike cold-call selling Ranch Style Beans, I suppose. “My first assignments were representing City Public Service in ‘pole cases’ where someone would run into an electric pole, and the insurance company would not pay CPS. I got a lot of jury trial experience there,” says Luke. Then a big case came along in Luke’s third year as lead trial lawyer in the Sarita Kenedy East will contest, representing a legatee under the will, the Oblate Fathers of Mary Immaculate. It was a seven-month jury trial in Corpus Christi, interrupted for two months due to Hurricane Celia, a trip to the Texas Supreme Court, a bench trial on remand, and another trip to the Texas Supreme Court. In the end, Luke’s client prevailed, acquiring a portion of the Kenedy Ranch with 1,000 mineral acres of rich oil and gas production in Kenedy County. Luke was also on the ground floor doing legal work on the birth of Southwest Airlines, working with Herb Kelleher, who would one day become the airline’s celebrated CEO. “Herb was a partner at Matthews at the time,” Luke says. “Herb was a genius and a joy to work with, who chain-smoked, drank Wild Turkey, and worked twenty hours a day. I never left the office when Herb wasn’t still there.”

But in the midst of his early years of private practice, Luke was diagnosed with central serous macular disease, an incurable condition of the eyes with no known treatment, and lived from that point on with the bleak prophecy that one day his condition would develop into blindness.

Luke later moved with Kelleher to join the firm that would be known as Oppenheimer, Rosenberg, Kelleher & Wheatley, where he practiced for several years as a partner, continuing to work on Southwest Airlines cases. At some point, he realized that he would not gain the stature of the name partners, so he started a firm with Jim Cliffe, called Soules & Cliffe, then a firm with John McCamish, named Soules & McCamish. After a few years, Luke founded the firm Soules & Wallace in the early 1980s. It was a huge turning point, and the right move.

As a trial and appellate courtroom lawyer, he has tried to verdict more than 100 jury cases and has argued as lead appellate counsel over 50 appellate court cases. He has argued before the Supreme Court of Texas, Fifth and Eleventh Federal Circuit Courts of Appeals, briefed for appellees cert denied cases in the Supreme Court of the United States, and argued at every appellate court in the State of Texas except the 11th Court of Appeals in Eastland, Texas. In no particular order, here are some of his greatest epic battles. He defended Halliburton, the parent of Brown & Root, in a $20-billion claim involving nuclear power plant construction at the South Texas Nuclear Project. He was part of the plaintiff Pennzoil team litigating against Texaco for tortious interference with the Getty Oil acquisition; the case with the largest jury verdict in American history ($10 billion), that, after appeals and the Texaco bankruptcy, was ultimately settled for $3 billion. He represented the plaintiff Hermann Hospital Estate to recover $2 million in funds from one of the corrupt trustees who looted the hospital’s charitable trust out of millions. He and Ricardo Cedillo represented defrauded Mexican investors against Walmart in the largest jury verdict ($628 million) in Bexar County history. He represented plaintiff Valero in recovering $12 million against a refinery services contractor in connection with an explosion at the refinery. He successfully defended Disney to a jury verdict rejecting antitrust monopoly claims under the Sherman Act. He represented plaintiff DPT Laboratories and recovered a $45-million settlement for the expropriation of Lubriderm lotion trade secrets. He represented plaintiff McLean Trust, recovering $1.5 million for a botched uranium strip mine. Barry Chasnoff and he protected the patent of Dr. Julio Palmaz, inventor of the original heart stent. And he represented the women plaintiffs in the several appeals during the silicone breast implant litigation against the Dow companies. He’s been on the plaintiff and defense counsel sides of cases where lawyers have been accused of wrongdoing, disciplinary violations, or negligence, and as such, he became Board Certified as an ABA American Board of Professional Liability Attorney to go with his Texas Board Certifications in both Civil Trial and Civil Appellate practices. As one can see, Luke Soules does not shy away from complex, scientific, or difficult cases, and he does not mind the money, either. And your phone does not ring for these types of matters unless you have the reputation. “One of the reasons I got to work on so many big cases that were not in San Antonio was that I had a statewide reputation from my work on the rules advisory committee and from my bar activities,” Luke says, citing referrals he got from Houston legal giants Jim Kronzer, who got Luke involved in the South Texas Nuclear Project litigation and the Pennzoil versus Texaco case, and John O’Quinn, who was plaintiff’s’ lead trial counsel in the breast implant litigation.

Legally Blind

During this time, as if the gods had somehow been angered in the wake of victory, Luke’s vision started to noticeably fail. “My vision started getting progressively worse in the 1990s,” Luke says. Then around 2005, a trip to renew his driver’s license didn’t go well. He couldn’t pass the vision test and was declared legally blind. “It was a tough transition to have to start asking for help in vision-dependent activities,” he says. “I had to decide what to do with the law firm, which was about twenty lawyers, and about thirty support staff. We had an amazing group of compatible, talented people. I was one of the main rainmakers, and we decided together that the others could be better served by relocating when I left. When the firm disbanded, many were welcomed at the prestigious law firm Langley & Banack, and we were able to help place every lawyer and employee in secure positions in other jobs at least equivalent to their Soules & Wallace jobs,” Luke adds, “I’m very proud of us for that.”

There are not too many living people with an award named after them. But in 2008, the Litigation Section of the State Bar of Texas established the Luke Soules Award, given each year in January. The award is given to an attorney who embodies excellence in the practice of the law and exemplary service to the State Bar. It is designed to annually recognize a Texas legal practitioner who demonstrates outstanding professionalism and community impact. Appropriately, the very first recipient of the Luke Soules Award was Luke himself.

After his firm closed, Luke decided to take another shot at practicing law, also joining Langley & Banack, where he had to learn new software and technology to assist with his blindness (let’s just say Luke was not into computers much before then). “I got my computer training from the Lighthouse for the Blind, and at no charge,” says Luke. “I am most grateful for that.” He still had one more big case left in him. In 2009, he tried his last commercial case, a patent infringement matter, recovering a jury verdict of $76.2 million. Since then, he’s done only pro bono work, representing underserved persons and families in Texas.

“I got started doing pro bono work when I got on the ad litem wheel at the courthouse, and then I kept getting calls from the families in need of other legal help,” says Luke. “I get a lot of personal satisfaction in helping people. I’m now trying to get a new and innovative program started for equal access to justice for the poor and underserved with a combination of support from law schools, the legal community, and philanthropic organizations. We are serving less than 10% of the need right now,” he says.

Many Thanks

You’re probably wondering how anyone can do so much in a career and still have a personal life. There’s a framed newspaper feature article on the wall of Luke’s office, the gist of which is that Luke Soules is sort a one-man show. I asked Luke about the article. “I didn’t like that article at all,” says Luke. “It implies that I do everything myself and I had no help, which is absolute nonsense.” So here we make an attempt to correct that, risking that a deserving person might be unintentionally left off the list:

“I had the support of my family. I’ve had the support of the very best of partners, associate lawyers, and staff, and my assistant Melanie Vaneck, paralegal Holly Simmons, and secretary Genie Canedo, all of whom who worked for me for thirty years. Now I have my assistant and right arm, Cheryl Seibert, an Aggie and a CPA, who works with me every day. And my dear friend and profoundly accomplished lawyer Chris Negem takes time from his busy family law practice to meaningfully support and contribute to our pro bono efforts. Over the years, I have worked with so many great lawyers in my law firm. Of course, Justice James Wallace, retired Justice of the Supreme Court of Texas, and his wife Martha, were highlights of my professional and personal experiences. And Jim Cliffe, my first partner at the original Soules & Cliffe, Susan Patterson and Suzanne Cowper who also worked on the Dorsaneo & Soules book, trial lawyers Richard Butler and Darryl Carter, and appellate lawyers Sara Murray, Rob Ramsey, and Sarah Duncan who became a Justice on the Fourth Court of Appeals. And so many in other areas of our law firm’s practice,” says Luke.

“I also learned that, from time to time, I needed family-time off, so I made it a point to take a week vacation every quarter, which I was able to do with the help of my colleagues.” he says. “More days of vacation broken into shorter stays kept me connected to my practice while accommodating regular quality time with Andrea and my four daughters—Laura Nell, Brett, Carol Lee, and Sydney—and my son Luther IV.”

In 2025, Luke received two more prestigious lifetime awards. The Texas A&M College of Arts & Sciences awarded Luke its 2025 Medal for Social Sciences, awarded annually to only one alumnus by the College “honoring career excellence and social commitment as a Distinguished Former Student.” And the Texas Bar Foundation awarded him the 2025 Outstanding 50 Year Lawyer award, given since 1974 to only 153 Texas lawyers who “manifested adherence to the highest principles and traditions of the legal profession and service to the public in the community in which he or she lives.”

It has been an odyssey for Luke Soules, who has practiced law for fifty-seven years now. To this day, he gets excited about the challenge of practicing law at whatever level. “I’ve done over 6,000 hours of pro bono work,” he says. “I’ve got one pro bono case right now with over 2,000 hours, representing an elderly blind woman trying to save her homestead.” I asked him why he keeps doing it. “I enjoy the people and the challenges, and I guess I never got tired of it,” was his simple answer. So don’t underestimate Luke Soules. Like the hero Odysseus of Greek mythology, a warrior-king surviving many trials, almost unheard of for years, he returns as an old man to open up a can on his opponents.

Steve A. Peirce is Of Counsel with the San Antonio Office of Norton Rose Fulbright. He recommends the 1997 mini-series The Odyssey, the 2000 Coen Brothers movie, O Brother, Where Art Thou (based on The Odyssey), and eagerly awaits the upcoming 2026 Christopher Nolan feature film version of The Odyssey. Steve can be reached at (210) 270-7179 and steve.peirce@nortonrosefulbright.com. And many thanks to Andrea M. Soules, Susan R. Burneson, and Luther H. Soules IV for background information and research, and, of course, to Luke Soules for sharing his time and stories.