26 minute read

the hive

MASK METAMORPHOSIS:

Embrace the New Norm

BY KAITLYN CHRISTY

IN THE WAKE of the Covid-19 pandemic, face masks went from being something you’d see in an apocalyptic movie to everyday fashion.

A creative collaboration between Farasha, a fashion consulting company, and MANICPROJECT, a Salt Lake City photographer, aimed to shine a bright light on the unknowns of COVID-19. Their message? This is a time of renewal. A moment to reset. An opportunity to listen and learn. To be better humans. To be humble. To be environmentally responsible. To make more socially conscious decisions. To support our communities and one another. To stand up for what is right. To show more empathy. To be kinder. To redefine purpose. To be more present. And to live in the moment.

And because we’re all sporting masks, why not be fashionable? They’ve crafted stunning high-fashion face coverings to help bring individuality and style to the world. Because while wearing a mask is a selfless way to keep others and yourself safe, it could also be a way to flaunt yourself. Basically, if you must wear a mask, wear it well.

Find out more at farashastyle.com.

PHOTOS MANICPROJECT

HOLE IN ONE

A perfect pandemic-friendly hobby, even for skeptics

BY JOSH PETERSEN

TO ME, GOLF HAS always just evoked images of stuffy businessmen in visors, and it is still officially the most boring sport to watch on TV. But I have to admit that it’s the perfect socially-distanced sport. A way to be outside, completely solo or with a small group of friends, golf is the rare sport where six feet of distance is an asset. Plus, when you get sick of hiking, scenic courses are an ideal way to take in a Utah spring, from the sweeping vistas of Park City to southern Utah’s dramatic red rocks. Courses are taking extra precautions to reduce COVID-19 risks, from sanitizing on-course ball washers to disinfected carts. Personally, I’m most intrigued by something called GolfBoards, a mash-up of singlerider motorized scooters and golf carts that are ready to ride at several Utah courses. As the weather warms up, courses in northern Utah are reopening or expanding their hours, while locations down south are open all year.

RED LEDGES’ TEE BOX

BONNEVILLE GOLF CLUB

954 Connor Street, SLC slc-golf.com 801-583-9513

ENTRADA AT SNOW CANYON

2537 W. Entrada Trail, St. George golfentrada.com 435-986-2200

FOREST DALE GOLF COURSE

2375 S. 900 East, SLC slc-golf.com 801-483-5420

RED LEDGES

205 Red Ledges Blvd., Heber redledges.com 877-733-5334

HOMESTEAD GOLF CLUB

700 N. Homestead Dr., Midway playhomesteadgc.com 435-654-5588

SAND HOLLOW

5662 W. Clubhouse Dr., Hurricane sandhollowresorts.com 435-656-4653

THANKSGIVING POINT GOLF CLUB

3300 W. Clubhouse Dr., Lehi thanksgivingpointgolfclub.com 801-768-7401

VICTORY RANCH

7865 N. Victory Ranch Dr., Kamas victoryranchutah.com 435-785-5000

FATHER AND SON PUTTING AT RED LEDGES

Ultimate Paint Protection

originalclearbra.com Salt Lake City . St. George

(801) 486-7668 (435) 673-3114

the Utah Original

PHOTO USED BY PERMISSION, UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

WHAT SALT LAKE LOST

Social media connects twentysomethings to a city they never knew

BY JOSH PETERSEN

THE PHOTOS ARE of familiar places, but the details are practically unrecognizable. Miles of streetcar tracks run through downtown Salt Lake City. Is that an amusement park in Sugar House? And why are there crowds of finely dressed people walking in the middle of Main Street—not on a Conference Weekend, mind you, just a regular day?

Snapshots of life in early 20th century Salt Lake City are gaining new life online, notably in a popular Twitter thread, mournfully titled “What Salt Lake Lost,” and the Instagram account Old Salt Lake, that’s profile reads: “Salt Lake is dope—and so is its history.”

The audience enjoying these dope images is mostly millennials and zoomers decades removed from this lost Salt Lake. As a generation comes of age in an almost entirely new city, many are looking to the past and wondering what went wrong. This version of Salt Lake had what many young urbanites now value: easily accessible public transportation, walkable streets, local businesses (open late), and

PHOTOS USED BY PERMISSION, UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

PHOTO (OPPOSITE

PAGE): RIDERS AT THE MOTORCYCLE RACE TRACK ON FIELD DAY AT THE WANDAMERE RESORT, 1912.

PHOTOS (CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT):

WOMEN RELAX AT WHAT IS BELIEVED TO BE SALTAIR BEACH, DATE UNKNOWN

MAIN STREET, INCLUDING THE OWL DRUG CO., WILSON HOTEL AND WALKER BANK, 1943

PEDESTRIANS WALK PAST DARLING STORES ON MAIN STREET, 1951

AN OLDSMOBILE PARKED AT THE BASE OF ANDERSON TOWER, WHICH WAS RAZED IN 1932, ON A STREET, 1919

MAIN STREET, INCLUDING BENNETT’S PAINT, WALGREEN DRUGS, CONTINENTAL BANK AND TRUST COMPANY AND WILSON HOTEL, 1938

A TRAIN CAR GOING UP EMIGRATION CANYON, 1909

distinctive architecture. The Twitter thread and Instagram feeds often play before-and-after with the images, with side by side comparisons that demonstrate what’s changed in specific neighborhoods. It’s fun but also a little wistful. In the last 100 years, Salt Lake City’s streets and neighborhoods have transformed. And, in many cases, dull-high rises have sprung up alongside cookie-cutter condo towers and chain restaurants and parking garages squat where once stately, architecturally significant buildings stood.

These images, rediscovered by a new generation, raise questions about what we want our city to be. They especially resonate as Salt Lake works through another period of transition. Rapid population increases and new economic opportunities promise progress, but urban growing pains also threaten much of what makes our city unique. As more changes loom, this curation of culture feels like both an elegy and a call to action. Find more images @olymasic on Twitter and @oldsaltlake on Instagram.

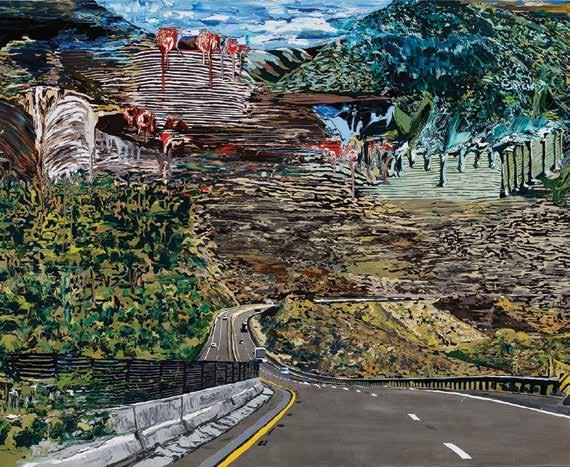

(BELOW) Mountain with Crepe Cake, enamel and acrylic on canvas by Yujin Kang; (RIGHT) By Annelise Duque

LOCK DOWN RESIDENCE

Local artists find safe haven at UMOCA

BY JOSH PETERSEN

ACLOUD MADE UP of the cloud — a mass of desktop files shaped to resemble non-digital fluffy formations. A surreal mountain landscape that turns into a layered crepe cake. A playful homage to 1950s garden magazines. These are just some of the inventive pieces by the current Artists in Residence at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art.

Since 2013, UMOCA’s Artist in Residence program has provided a crucial support system for local artists. Let’s face it: it’s not easy to survive as an artist in Utah. Yes, there’s plenty of local interest in the arts, but there are plenty of obstacles, too. It is still a relatively small community that doesn’t always have established networks for creators. The program provides artists studio space, workshops with other professionals and the opportunity to showcase their work in a dedicated gallery space at UMOCA. Basically, the goal is to build a strong community and keep great artists in the state.

The program’s current roster highlights the wide-ranging diversity of local artists. All of the residents are Utah-based, but their backgrounds, styles and mediums are all distinctive. The Utah art world is wide enough to include politically provocative ceramics from Houston native Horacio Rodriguez and abstract paintings by the Korean artist Yujin Kang, and, as the entire industry reels from the coronavirus pandemic, UMOCA is setting the foundation that allows these creatives to thrive.

LOST IN THE SAUCE

Red sauce makes a comforting comeback

BY JOSH PETERSEN

UTAH MAY NOT have a signature pizza style—or a real stake in the endless sauce vs. gravy debate that rages on back East—but that doesn’t mean there aren’t places to get mouthwatering Italian-American cuisine. Salt Lake has its share of Italian fine dining, from acclaimed favorites like Valter’s to new kids on the block like La Trattoria di Francesco, but that’s not what we’re talking about here. These are the “red-sauce” establishments: think redcheckered tablecloths set with simple, classic dishes. The term can be pejorative, but it doesn’t have to be. Done right, these mom-and-pop eateries serve the best versions of the basics in a friendly setting—comfort food in every sense of the word.

Plenty of Utah neighborhoods have longrunning favorite spots, like SIRAGUSA’S in Taylorsville. More recent openings confirm that red-sauce is rising in Utah.

OSTERIA AMORE

224 S. 1300 East, SLC osteriaamore.com / 385-270-5606

SICILIA MIA

4536 S. Highland Dr., SLC siciliamiautah.com / 801-274-0223

CELESTE RISTORANTE

5468 S. 900 East, Murray celesteristorante.com / 801-290-2913

MARCELLA HAZAN’S RED SAUCE RECIPE

Marcella Hazan, who changed the way we cook Italian food, published The Classic Italian Cook Book (1973), More Classic Italian Cooking (1978) and, collected in one volume, Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking, in 1992. Her 1997 book Marcella Cucina won the James Beard Foundation Book Award for Best Mediterranean Cookbook and the Julia Child Award for Best International Cookbook the following year. Craig Claiborne once said of Hazan’s work: “No one has ever done more to spread the gospel of pure Italian cookery in America.”—MBM

INGREDIENTS: 2 cups tomatoes, in addition to their juices (for example, a 28-ounce can of San Marzano whole peeled tomatoes) 5 tablespoons butter 1 onion, peeled and cut in half Salt

DIRECTIONS: Combine the tomatoes, their juices, the butter and the onion halves in a saucepan. Add a pinch or two of salt. Place over medium heat and bring to a simmer. Cook, uncovered, for about 45 minutes. Stir occasionally, mashing any large pieces of tomato with a spoon. Add salt as needed. Discard the onion before tossing the sauce with pasta. This recipe makes enough sauce for a pound of pasta.

IT TURNS OUT there’s no such thing as Italian cuisine—not with 20 diverse regions in the country and a population of almost 60 million. Northern Italy has a whole different set of influences than Southern Italy, and Sunday gravy is simply not the national dish. Here’s a look at some of Italy’s most prominent regions—and a typical dish from each.—MBM

REGION: EMILIA-ROMAGNA

WHERE IT IS: North central WHAT IT IS KNOWN FOR: Known as “Italy’s food basket,” this is foodie heaven, with bragging rights for prosciutto, mortadella, ParmigianoReggiano cheese and Balsamic vinegar. Many consider this region to offer “classic Italian” dishes. TYPICAL DISH: Bolognese sauce, tortellini REGION: CAMPANIA

WHERE IT IS: Southeast coast WHAT IT IS KNOWN FOR: This ancient land was settled by the Greeks and is the site of Mount Vesuvius and Pompei; its fertile volcanic soil produces bountiful vegetables like the famous San Marzano tomatoes, figs and lemons. This is where Naples is, the hallowed birthplace of pizza. TYPICAL DISH: Pizza, buffalo mozzarella

REGION: LOMBARDY

WHERE IT IS: North central WHAT IT IS KNOWN FOR: Italy’s industrial region and its fashion capital, Milan favors risottos and polenta, veal, beef, butter, cow’s milk cheese and freshwater fish. TYPICAL DISH: Risotto, osso bucco REGION: PIEDMONT

WHERE IT IS: Northwest corner WHAT IT IS KNOWN FOR: This region—and its white truffles—has somewhat elegant cuisine, lovely wines like Barolo and Barbaresco, and makes great chocolate desserts. TYPICAL DISH: “Warm dip” (Bagna caôda) made by slowly cooking chopped garlic with oil and butter, anchovies, peeled walnuts and served with Jerusalem artichoke, endive, sweet pepper and onion in a terracotta pot.

REGION: SICILY

WHERE IT IS: Island off the southwest coast WHAT IT IS KNOWN FOR: The largest island in the Mediterranean, Sicily hearkens back 10,000 years before Don Corleone lived there. Its food has Greek, Arab, Spanish and French influences and favors antipasti, pasta and rice dishes, and stuffed and skewered meat. It is also known for its candied fruits and marzipan. TYPICAL DISH: Caponata, veal Marsala, pasta with sardines

REGION: TUSCANY

WHERE IT IS: North central coast WHAT IT IS KNOWN FOR: This is one of Italy’s art and cultural treasures, highlighted by Florence, home of Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, the Medicis. Its food has been described as the “art of understatement” with spices like thyme and fennel, and is well known for its ravioli, tortellini and fish and seafood. Not to mention Chianti, Dr. Lecter’s favorite. TYPICAL DISH: Pecorino cheese, steak alla fiorentina, panzanella (bread salad to you)

WHAT’S KEEPING UTAH’S LIGHTS ON?

Little seems capable of upending Utah’s fossil fuel status quo

BY TONY GILL

FLIP A SWITCH, and the lights come on. It seems simple and innocuous, and for many, it’s where the story begins and ends. But energy in Utah is anything but simple. Every phone charged, every movie streamed and every room illuminated comes with a cost. In the Beehive State, more than in most places, that’s paid in carbon.

Utah generates 64% of its electricity by burning coal. That proportion has declined substantially since 2001 (94%) but it still dwarfs the national figure of 23%. Utah has the worst average air quality index ranking of any state and is economically vulnerable as climate change affects snow conditions. A coordinated, concerted effort between residents, local industry and the state government to back cleaner electricity generation is needed, but that’s not what’s occurring.

This reality came into acute focus in October 2020 when the Utah Public Service Commission (PSC) ruled Utah’s monopoly electricity provider Rocky Mountain Power could reduce the amount it pays customers for electricity produced by residential solar by roughly 40% from 9.2 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh) to 5.969 cents/ kWh in the summer and 5.639 cents/kWh in the winter. The decision was a blow to the residential solar industry in Utah. And while the rate reduction was sold as a compromise between RMP’s original low ball valuation for residential solar of 1.5 cents/kWh and the national average of 22.6 cents/kWh, according Vote Solar, a non-profit advocacy group, there is a huge gap.

The chasm in estimates and the subsequent ruling doesn’t represent reality. “It looks like a compromise, but RMP got what they wanted in hindering the economic viability of residential solar. Their initial figure was a lowball that effectively moved the goalposts.,” said an engineering consultant who has worked extensively with Berkshire Hathaway Energy, who spoke to us on the condition of anonymity. RMP is a subsidiary of Berkshire.

RMP has been chipping away at residential solar for some time. Prior to 2017, residential solar customers who sent excess power back to the grid were compensated with what’s called net metering, which meant the amount of power generated by customers was paid back to the homeowner, ostensibly paying solar customers the retail rate for energy they produce. RMP argued that the rate wasn’t sustainable because those customers didn’t have to pay for transmission and energy storage, so they pursued the reduced “export credit” of 9.2 cents/kWh for new solar customers as part of a transition program. The change diminished the benefit of new home solar, and installations slowed from more than 12,000 in 2017 to about 3,500 last year.

RMP’s efforts were aimed at avoiding a death spiral for coal production. If more customers are moving to solar, this would, in turn, raise rates for coal, which, in turn, would further drive more customers towards solar. RMP’s monopoly was threatened by a market-based solution available to notoriously frugal customers in a state with more than 300 sunny days per year, so they tipped the scales. Centralized utility monopolies have long been considered prudent because they eliminate overlapping infrastructure—RMP owns all the transmission lines, substations, etc.—but credible, de-centralized competition, like solar, is a threat. RMP managed to set a rate to profit off power generated by residential solar customers.

Utah’s energy monopoly is proving resistant to competitive forces threatening coal, but even when market forces encourage the utility to stray from the status quo, politics can get in the way. RMP is a division of Pacificorp, which runs the Naughton coal-fired power plant in Kemmerer, Wyo., that supplies some electricity to Salt Lake City. Pacificorp’s own 2019 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) called for the early retirement of two Naughton units within six years, converting one unit to natural gas. Natural gas produces less carbon than coal and it’s more cost-effective. State and local lawmakers are pushing back to prop up the local coal industry against the wishes of both the utility and consumers.

“What we’re hearing are disingenuous solutions,” says Noah Miterko, Policy Associate for the Healthy Environment Alliance of Utah (HEAL). “There are valid concerns about an area’s tax base and peoples’ employment, but saying these jobs are going to be around long term isn’t true. The utility companies and the mining companies know it’s a lie. They’ll keep the jobs around as long as it’s profitable, then declare bankruptcy, give bonuses to the executives and sell the companies off for parts.”

Keeping the Naughton plant operating is just kicking the issue down the road, and continuing to generate power by burning coal will ultimately cost consumers in cash on their energy bills and via environmental calamity. In a way, it’s surprising to see a deeply conservative area pushing for government intervention to prop up a struggling business, and the approach fails to confront a changing reality with solutions that will help the community in the long run.

“The inevitable is coming to a head a few years ahead of schedule. We need to reinvest in these communities economically. It’s not an apples-to-apples comparison, but we’re going to see the same kinds of issues in Carbon and Emery County in Utah eventually, and we need to be ready with solutions,” says Miterko.

But what’s to be done? When a market-based solution threatens the utility, they push back on customers. When the market pushes a utility away from coal towards a more efficient—though still fossil-fuel based—solution, legislatures enter the fray to disrupt adaptation. The climate crisis isn’t waiting on a benevolent form of capitalism to rise, nor is it waiting on an altruistic bureaucracy to act.

Miterko was less pessimistic, suggesting homeowners talk to solar

suppliers to assess if residential production can work for them. He says the faster we can normalize renewables, the better. While natural gas is preferable to coal, it’s still fossil-fueled based energy. Investing heavily in related infrastructure will lead to the same discussions we’re now having about coal several years down the line.

Essentially, the players are all hedging their bets, but meanwhile, time on the carbon clock is ticking. Miterko concurs: “It’s the business-as-usual plan. Solar and wind are becoming cheaper and more attractive but the transition will be too late for some of our concerns.” Solar subsidies are scheduled to phase out over the next five to 10 years, reducing incentive. The subsidies baked into the fossil fuel industry since its inception have never gone away. “Subsidies are designed to help gain a foothold, not prop up an industry indefinitely,” Miterko says.

If anything in Utah will have an effect, there is action regarding electricity production happening primarily at the municipal level. The 2019 Community Renewable Energy Act (H.B. 411) provided cities with the mechanisms to get to net-100 percent of electric energy from renewable resources by 2030. The Salt Lake City and Park City Councils were early adopters, and by the end of 2019, 24 municipalities comprising nearly one million RMP customers had committed to paying the cost of pivoting to renewable energy sources and removing fossil fuels from their portfolio. That level of participation and commitment can compel a utility—even one that’s a monopoly—to change the way they’re investing.

DIRT BAGGERS DONE GOOD

How the Salt Lake Climbers Alliance spearheaded Little Cottonwood Canyon’s newest recreational resource

BY MELISSA FIELDS

THIS IS MY FAVORITE part of the trail,” muses Julia Geisler, executive director of the Salt Lake Climbers Alliance (SLCA), as she steps over a series of large, flat granite stones, grouted with smaller versions of the same. The trail is the Alpenbock Loop, a new hiking, snowshoeing and climbing wall-access trail on the north side of the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon. With its sections of cobble-like paths and tidy stone staircases, reminiscent of stone masonry walkways you’d find in a centuries-old English garden, sections of this trail do indeed have has an almost artistic quality. And then there’s the breathtaking scenery: soaring granite walls and long views both up the canyon and into the Salt Lake Valley. But this section of the canyon wasn’t always so idyllic. Just a few years ago, the land where the Alpenbock Loop and its accompanying Grit Mill parking area are now located was marred by a spiderweb of social trails (paths worn into the land where no one ever

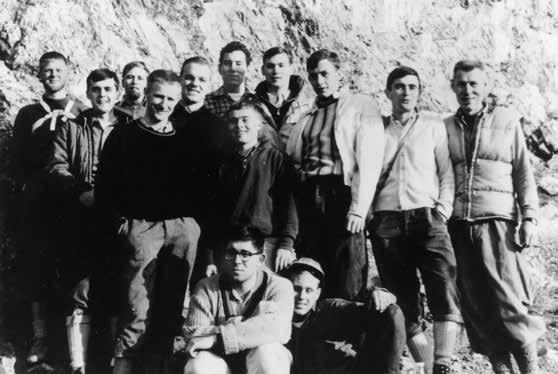

THE ALPENBOCK CLUB, CIRCA 1961 (FROM RIGHT TO LEFT): RICH REAM (THE CLUB’S UNOFFICIAL ADVISOR/MENTOR), TED WILSON, CURT HAWKINS, STAN FERGUSON, DICK REAM, RICK REESE, DICK WALLIN, BOB IRVINE, COURT RICHARDS AND GARY JONES. KNEELING IN FRONT: DAVE WOOD (LEFT) AND MILT HOKANSON.

Utah Climbing’s Non-Club

“Membership was informal as hell,” says Ted Wilson, describing how he and a group of “spirited first ascensionists,” most of whom attended Olympus High School, formed the Alpenbock Club in 1959. “We never organized, like getting a 501C3 or anything like that. At first, we did vote on new members but then we laughed at that and when someone wanted to join, we’d just sit around and ask each other ‘is he a good guy?’” Wilson says the club formed when he and his friends “got tired of climbing the same ten to twelve routes in Big Cottonwood” and started focusing on the base of Little Cottonwood. Other members include Rick Reese, Bob Irvine, Ralph Tingey, Jim Gaddis and Bob Stout. Wilson, in fact, made the first recorded ascent in Little Cottonwood Canyon in 1961, a route rated 5.6 that he called Chickenhead Holiday. The Alpenbock Club has never disbanded.

takes the same route twice) and abandoned industrial detritus. That was until the SLCA figured out a way to accomplish the goals of a few by creating a resource for many.

The granite walls rising above the Alpenbock Loop first caught the attention of local climbers back in the late 1950s. This scrappy band of high schoolaged adventurers—including former Salt Lake City Mayor Ted Wilson—eked out some of the Wasatch Range’s first climbing routes. The Alpenbock Club and their friends had the Little Cottonwood climbing walls, known as crags in climber-speak, almost exclusively to themselves until the early 1990s. Then, the evolution of climbing gear opened the sport up to more than just the über-dedicated and more routes were developed both in Little Cottonwood and several other locales throughout Utah. By the early aughts, dirt baggers—an autobiographical moniker for climbers who chuck it all to climb, often living out of their car or van—from around the world were descending on Utah to climb, many lured by the reputation of the granite routes in Little Cottonwood.

Historically and generally speaking, crags are developed without foresight as to how climbers will get to them. And so, because they carry heavy packs filled with ropes, harnesses, and other climbing gear, the path or approach to a crag is usually a straight line with little regarding for topography and plant life. Over time, the paths climbers beat to a crag can cause irreparable scarring, erosion and unnecessary danger—the steep and loose social trails leading to the Little Cottonwood crags were more challenging than the climbing routes they accessed.

“The network of social trails at Little Cottonwood, not to mention the damage that was occurring to the ecosystem and watershed, was not sustainable,” said Cathy Kahlow, the now-retired U.S. Forest Service’s Salt Lake District ranger from 2008 to 2016. The SLCA was formed in 2002, and in 2011, when Geisler became its first and only paid staff member, Kahlow approached her about solving the overuse problems in Little Cottonwood. “SLCA was founded on the mission of keeping climbing areas open by forming relationships with landowners where climbing areas are located and being good stewards of the lands where crags are,” Geisler says. “The popularity of climbing was really beginning to explode then, and so we knew we needed to do something in Little Cottonwood before that area was loved to death.”

It was clear early on that the access to the crags in Little Cottonwood would

SLCA VOLUNTEERS AND CONTRACTED STAFF BUILDING THE ALPENBOCK LOOP TRAIL

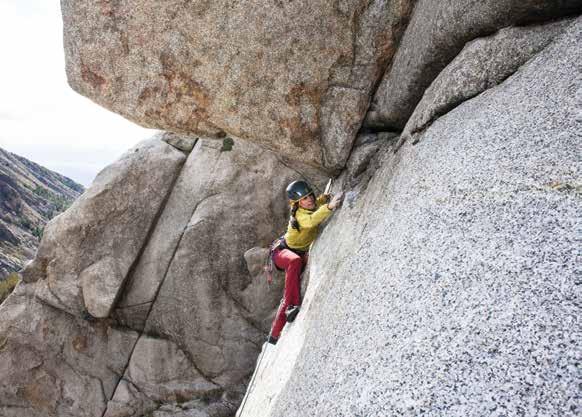

EVERYONE’S GOING UP

If it seems to you like everyone’s climbing these days, either in the gym or outside, it’s no wonder. According to the American Alpine Club, in 2018 there were 7.7 million climbers in the U.S.; not an insignificant number when you consider in the same year, 10.3 million Americans considered themselves a skier or snowboarder. With more than a dozen climbing gyms and world-class climbing areas peppered throughout the state, Utah is a bona fide destination for the sport. In fact, when sport climbing makes its Olympic debut in Tokyo this July, Utah native Nathaniel Coleman will be a Team USA member to watch.

JULIA GEISLER OF SLCA CLIMBING A ROUTE AT THE COFFIN IN LITTLE COTTONWOOD CANYON

WHEN YOU GO

The Alpenbock Loop can be accessed from two points: from the west at the Little Cottonwood Canyon Park ‘N Ride lot or from the east via the Grit Mill parking lot and Grit Mill connector trail. The route begins relatively flat from either direction before meandering up the mountainside over rock-stair switchbacks and through dense stands of Gambel oak. At the top of the loop, signed climbing access spur trails lead north up to world-famous crags ostensibly named The Coffin, The Egg and Bong Eater. (Referring to a piece of climbing gear, not something more nefarious.) Hikers should stay on the main Alpenbock Trail, as rockfall is possible at the base of the crags from those climbing above. The connector trail and lower part of the loop pass by the Cabbage Patch and Secret Garden, popular bouldering areas between the trail and the canyon road. Please note: the Alpenbock Trail is within the watershed, so dogs are not allowed. require professional planning and major funding, which meant a multi-year effort in a typical federal government timeline. “It takes a long time and many people to enact any kind of change on federal lands,” Kahlow confirmed. This is particularly true in regard to climbing, which is not a traditionally recognized use on Forest Service lands in the same way activities like hiking, picnicking, fishing and even skiing are.

So, Geisler began pounding the pavement. Some of the organizations and individuals she hit up to help get the Alpenbock Project done include Trails Utah, the Cottonwood Canyons Foundation, the Mountain Accord (now the Central Wasatch Commission), Wasatch Legacy Project, Snowbird, Alta, REI and others.

The physical part of the project finally kicked off in 2014 with the removal of the old poultry grit mill. It took three years of fundraising before replacement of the treacherous social trails could begin in 2017. The Alpenbock Loop and Grit Mill connector trails were completed in late 2018. And the project’s last piece, the 34-stall parking lot and restroom, was completed in November 2020.

To date, the Alpenbock Loop Trail is the largest climbing access trail project completed on U.S. Forest Service lands in the nation. It was a major catalyst in the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest’s current work in creating a rock climbing management plan. And, after cutting its teeth on this project, the SLCA is now focusing on more than just trails. They launched the Wasatch Anchor Replacement Initiative, a campaign to replace bolts and anchors on climbing routes throughout the state, some of which date to the Alpenbock Club’s active era.

Why should non-climbers care about the Alpenbock Loop Project? First, it’s an illustrative and refreshing example of how the public sector and private interests can work together for the benefit of many. Second, it is an important piece in a greater vision for potential connectivity to other trails in that area, including the Bonneville Shoreline Trail and Temple Quarry Trail (As it is now, this trail is not really a significant contribution to the Wasatch Mountain’s vast anthology of bucket-list trails—at just a mile-and-a-half long, most dedicated hikers will find it way too short.) Moreover, it is one more place where, during these tough times, families can get outside and immerse themselves in the healing power of nature. And maybe even meet their first dirt bagger along the way.

PHOTO JOHN VICKERS

PARK CITY

LIFE ON THE OTHER SIDE

PHOTOS SCOT ZIMMERMAN

DRESSED FOR SUCCESS

BY JOSH PETERSEN

RIGHT NOW, WE’RE focused on filling people’s homes with happiness and joy,” says Beth Ann Shepherd, principal of Dressed Design. As a designer, Shepherd has brought her idiosyncratic style to the homes of high-profile clients across the country. Now, she is sharing her fresh, joyful design approach with Dressed Design’s new retail location in the heart of Park City.

Along with custom furniture, Dressed carries vintage Les Paul guitars, whimsical pieces from local artists and old-school board games, including a Monopoly set made of glass, gold and crystal. “Everyone’s first response is always the same word: wow,” she says. “This store is going to continually evolve.” 692 Main St., Park City, 435-658-9857, dresseddesign.com