Science Explorations

Saint Ann’s School

VOLUME 12

2022-2023

A Return to the Aether: Retracing the Michelson-Morley Experiment and its Impact on the Pursuit

Hungry Hitchhikers: The Egg-Laying Patterns Of The Spotted Lanternfly

Anna M. Mentor: Liz V.Abstract

Spotted Lanternflies are an invasive insect that most likely arrived to the U.S. as stowaways on a shipment of stone in 2012. In 2014, the first infestation was discovered in Pennsylvania. Now, it is 2023 and they have spread to 14 states in only 11 years. Due to their large size and ample appetite for their diet of plant sap, these bugs cost the U.S. hundreds of millions of dollars annually, not to mention the decimation of plant life not equipped to handle their presence. Squishing them is one way to help fight this ecological disaster, but I was curious as to how they could spread so effortlessly, as they are somewhat clumsy fliers. I learned that they are hitchhikers, catching rides around the country either as live adults or as eggs. I was interested mainly in their egg-laying patterns, because to squish one spotted lanternfly is to squish one spotted lanternfly, but to squish an egg mass is to squish up to 60.

I began my research in the fall by capturing egg-laying adults to see what surfaces they preferred for laying. Two laid egg masses in the cage, and over the winter I collected more from a local arborist. I then set up an experiment to expose the egg masses to different amounts of light and heat. While I waited for the eggs to hatch, I went on a few expeditions to sites where eggs were laid around the city. I recorded their preferences for certain plant species and conditions, learning that they largely prefer to lay on the underside of tree branches or other surfaces, rather than vertical surfaces. This is most likely for the shelter that a more horizontal angle offers.

Then, in late January, the egg masses in the lab began to hatch, several months earlier than they would have in the wild. After conducting these experiments (and a few others along the way) I observed a few key pieces of information. I observed that they have some preferences for what surfaces they like to lay on, and at what angle. I observed that the adults infest some species of trees far more than others. I observed that the heat exposure of being indoors for those first months of early winter appears to be a temperature cue to hatch, meaning that if they spread to a climate that is warmer during the winter, they could hatch and mature much earlier in the year.

Researching invasive species is important, as we can help slow the progress of environmental crises like this one. Ultimately, however, we must remember that it was human movement that brought them here, even if it was an accident.

Introduction

Spotted Lanternflies (SLFs) are a species of the order Hemiptera, also known as true bugs. They are closely related to cicadas, aphids, and leafhoppers, and much like these other members of their order they feed with mouths designed to pierce into plants and suck out the sap within⁴ . Spotted lanternflies are relatively large insects (about an inch long). This means that they make quick work of their plant food sources, causing significant injury and often the death of even the hardiest. This is why their arrival to new habitats, like the United States, presents a threat to our native flora. Considering the U.S. has nearly 900 acres of farmland⁵ , a new pest is quite troubling.

Spotted Lanternflies are native to China, arriving in Pennsylvania on a shipment of rocks in September of 2014. They have since spread to 14 states¹; Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, and West Virginia. They arrived in New York City in July of 2020. Their life cycle is as follows; the eggs hatch in May or June, live through several nymph stages until they are mature flying adults in July, by November they lay eggs and start the cycle all over again. I became aware of them the following summer, and when I was deciding what to research for my Independent Science Research project they quickly came to mind. I knew I wanted to study an invasive species, and the effect of this particular organism was unfolding in real time. This made it a pertinent area of research. Additionally, the study of these insects is much easier in a city setting. While there are significant infestations in our city’s parks, they are quite easy to examine up close on, for example, a sidewalk tree. This would not be possible in a more rural environment, or behind the fences walling farmland. This was specifically useful because I was often observing well-camouflaged egg masses high in the tree canopy

Materials and Methods

Phase 1:

I wanted to test if Spotted Lanternflies have a preference for what texture or color of surface they lay on. I set up two bug enclosures; the first one with two smooth paper panels, one brown one white, to test color preference. I chose brown and white because egg masses are bright white when laid and then shift to a gray-brown as they mature. The second bug enclosure had two panels; one was smooth paper, the other was covered with bark collected from a London Plane tree. This was to test texture preference.

I collected live Spotted Lanternfly adults, mostly from a wild grape vine on the corner of Middagh & Willow street. I caught them using a butterfly net, a small plastic box, and my hands. The insects were relatively slow, as they were reaching the end of their life cycle as the weather got colder. I collected these insects in groups of five to seven at a time. I then brought them to

the enclosures and released them inside. I tried to collect mostly females that looked like they were about to lay eggs, meaning that they had a larger and more pronounced abdomen than usual. I also collected a few males and a small ailanthus plant to give the semblance of normal surroundings for the insects.

Phase 2:

I went on multiple walking trips to various locations around the city; one to Prospect Park, two to sidewalk tree infestations, one to a backyard, and one to a dog park. I used binoculars to better see the egg masses. I collected data concerning the tree species, the bark roughness, the height from ground, the bark color/ laying site color, and the orientation of the egg mass. This also gave me a chance to better understand what egg masses look like at all stages of development.

Phase 3:

I dissected several of the adults after they had passed away in the enclosures. I used a dissection microscope, tweezers, and dissection scissors.

Phase 4:

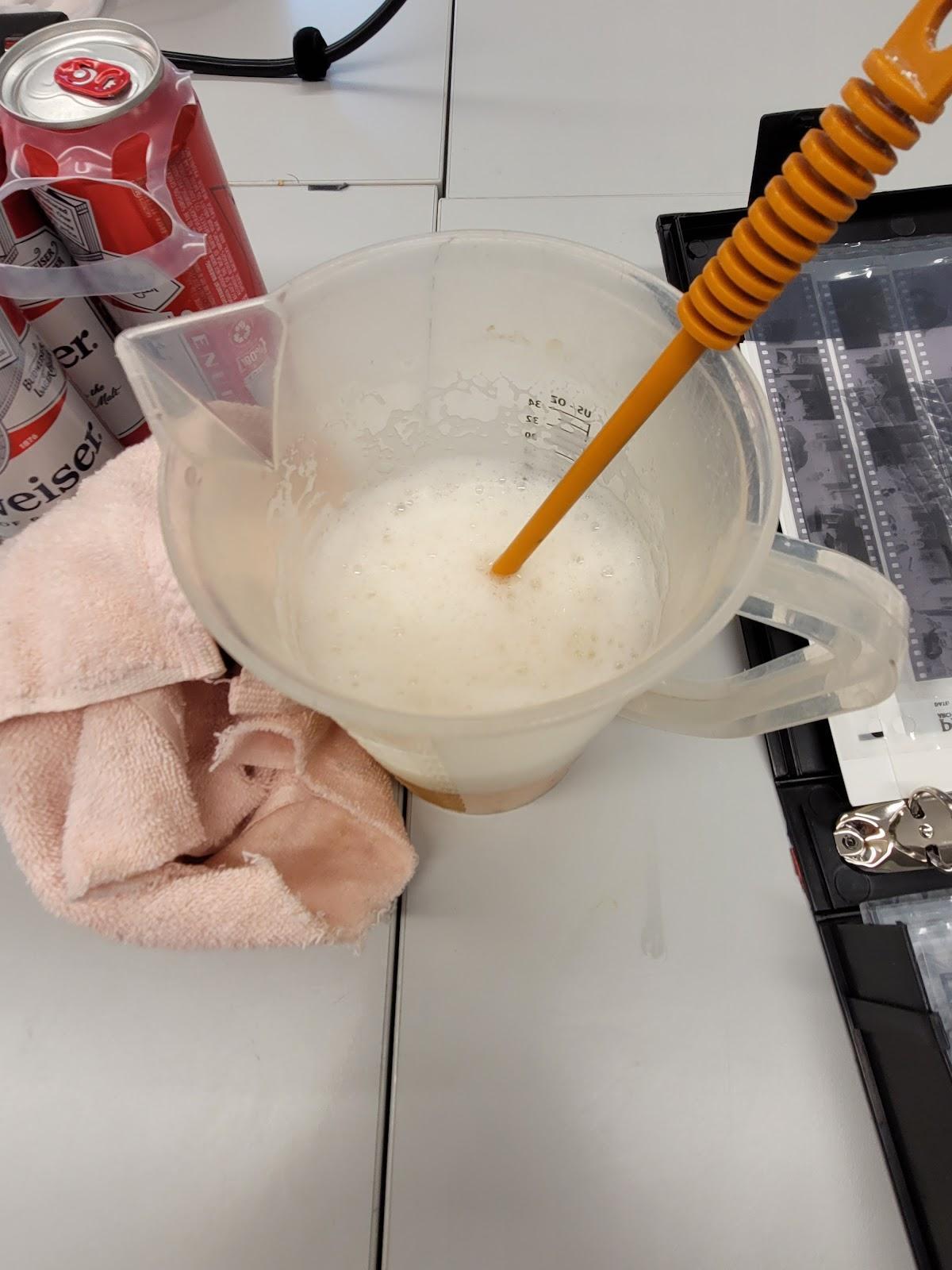

I was curious to see what environmental trigger causes egg masses to hatch. I set up my bug enclosures from earlier in the research process to test how several factors affected the hatching process. There were four sections in the three cages (one larger one holding two sections), as pictured:

Figure 1 is light no heat (the control), Figure 2 is heat and light, Figure 3 is heat no light (the heat is provided by the heat lamp pictured above, the black box within the larger cage is a crate with black cloth draped over it), and Figure 4 is Extended light no heat (a light on a timer of 5:00 AM to 7:00 PM lengthens the day to replicate the light exposure of their normal hatch time of late spring). There were approximately eight good condition egg masses in total on the tree limbs pictured here, two in each experiment. Two were laid in the lab by adults collected by me, the rest were obtained from a local arborist. I recorded the temperature next to the egg masses in each experiment each day until hatching.

Results

Note: Some of the graphs only contain data collected from Prospect Park. This is because it was the trip with the greatest number of sites and data to compare.

Discussion

Phase 1:

Spotted Lanternflies are voracious eaters, and unfortunately this meant that the one plant I placed in the enclosure was not enough to keep them alive for more than a few days. Nearly all died before laying. In the end, only two laid egg masses in the enclosures, both on the London plane bark of the texture enclosure. This reflects what I observed in the field, that a preferred laying site seems to be a bark with some texture, rather than a completely smooth surface. This does not necessarily mean that they won’t lay on many different surfaces, but if a better one is available they will choose it.

This phase really assisted me in becoming more familiar with the anatomy and behavior patterns of the species. The more time I spent with them, the easier it was to tell if they were male or female, about to lay eggs, or about to spring into the air and away from my net.

Phase 2:

From my walking expeditions I observed several things. The first is that the Spotted Lanternfly’s favorite tree species by far to lay on is the Ailanthus, or Tree of Heaven. This is an invasive species of tree that is already quite established in Brooklyn, and it also originally comes from China. In my analysis of the lanternfly’s relationship with certain tree species, I observed a phenomenon wherein the lanternfly would lay egg masses on a tree with a vine nearby Vines are much easier for nymphs to feed from, as they are softer and easier to puncture. You’ll often find nymphs feeding on young plants and vines rather than adult trees because of this. Whether the laying adults intentionally placed their future nymphs near a suitable food source, or were simply feeding on the vine and chose to lay close by I cannot say Both options are possible.

Another observation that I made was that in nearly 90% of the data I took, the egg masses were laid on the underside of tree branches rather than the trunk. This is most likely to provide protection against weather conditions. I also found that at two different sites that I surveyed (one in a backyard, one on a private sidewalk tree) there were masses laid on the underside of brownstone window sills. In at least one of the instances, I could directly observe that the trees nearby were either too crowded with masses or too far away to reach for tired, end of the life cycle adults. This is an issue distinct to the sidewalk sites, in that there is often a very low density of trees and plants to lay on. The windowsill was close by, and it was available real estate.

In terms of height that the insects laid from the ground, there was no discernable pattern. Generally, if the tree was taller, egg masses were laid higher off the ground and up into the canopy, but it was also difficult for us to confirm this as we could only see so much with our binoculars. There were also sites with tall trees and eggs laid barely off the ground. The bark color of the laying sites, as we observed, was often more on the gray side of brown, like the bark of the Ailanthus tree. I never observed an egg mass laid on a white surface to match the early stage egg mass.

Overall, these field examinations let me observe how spotted lanternflies lay their eggs; there is often one preferred tree, often an Ailanthus, that the adults had been feeding off of, and then when it comes time to lay they lay right on that tree. The trouble is that these insects live in great numbers, and there is never enough space for everybody. So, the egg laying adults clumsily fly to the surrounding trees (or window sills, or rock, or a number of other recorded surfaces) and lay there instead, in less concentrated clusters of egg masses. This makes it apparent, with practice, which tree was the one that might have first drawn them to this area.

Phase 3:

When dissecting the deceased specimens from our enclosures, we observed that a female that had already laid an egg mass had residue on the rear of her abdomen that appeared to be the egg mass adhesion substance. This was interesting to note because it provides a way to tell if a female has already laid without opening up her abdomen.

Phase 4:

Almost immediately after the set up of our entire heat and light exposure factor experiment, egg masses began hatching with no discernible distinction of which section they were part of. The masses had been inside our warm lab classroom for a few months, and the first to hatch was one of the egg masses laid in our lab (the other one never hatched, I’m not sure why). The rest were soon to follow in the coming few weeks. The first hatched on January 20th, 2023, and was laid on October 11, 2022. This January hatch date is four to five months earlier than they hatch in the wild. The nymphs showed no signs of maldevelopment, they even jumped and hid, exhibiting a strong survival instinct.

This shows that the egg masses most likely rely on a temperature cue to hatch, and this is concerning. If the Spotted Lanternflies are able to hitchhike farther south, to regions of the United States and other countries where the winters are milder or nonexistent, these insects could potentially hatch much earlier in the year, mature much earlier in the year, and do even more damage. To slow their spread, we need to instead spread information about their presence, so that actions can be taken to prevent further migration. What I learned most of all from this research project is that invasive species are living organisms. In the case of the Spotted Lanternfly, it is our fault as humans that they are here and damaging other species. It is our responsibility to try and undo what we’ve done, and to be more careful in the future regarding the haphazard and often destructive organism exchange that we have facilitated across the globe. We shouldn’t have to squish bugs.

References:

1. USDA APHIS | Spotted Lanternfly

2. Oten, Kelly, Spotted lanternfly confirmed in North Carolina | NC State Extension.

3. Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, Virginia Cooperative Extension, Spotted Lanternfly in Virginia

4. Cornell CALS, Spotted Lanternfly Biology and Lifecycle | CALS

5. USDA, Farms and Land in Farms - 2021 Summary February 2022

Melody and Memory: Music Therapy in Alzheimer’s Care

Kamala G.Mentor: Teresa C.

Abstract

Dementia is the general term for a condition that leads to the unnatural loss of cognitive function as one ages. Symptoms of dementia include memory loss, confusion, difficulty speaking or expressing thoughts, impulsive behavior, loss of interest in activities, and hallucinations. Alzheimer’s disease, which is the most common form of dementia, affects roughly 10.7% of the US population aged 65 or older. The amyloid hypothesis–one of the leading hypotheses for the cause of AD–proposes that AD is caused by the excessive buildup of amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau proteins, leading to neuron death and brain atrophy. This paper reviews current literature—including studies, reviews, and meta-analyses—focused on the efficacy of music-based interventions (MBIs) in AD and dementia care. Music has shown potential in both preventing and mitigating the effects of dementia. Studies have shown, for example, that musicians were 64% less likely than non-musicians to develop mild cognitive impairment or dementia, and MBIs can alleviate some symptoms of dementia, including cognitive decline, mood, and lack of sleep. Music therapy is the clinical and therapeutic application of music to accomplish individualized goals ranging from psychosocial development to physical rehabilitation. Currently, research on the efficacy of music therapy varies, with some studies reporting weak findings while others report positive outcomes relating to mood, sleep, cognition, and general quality of life. Through literature research, as well as direct observation and participation in actual sessions, this paper discusses the efficacy of music therapy in AD care in the following categories: cognitive function (memory and speech), behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, physical function, and social function. While music therapy can improve symptoms of AD and quality of life, there is a lack of evidence to support an increase in general daily function and independence in AD patients. In the future, however, MBIs may be able to incorporate emerging therapies, like gamma-frequency sensory stimulation–which has demonstrated an ability to modify AD in mouse models–and increase their efficacy in treating AD patients.

Introduction

Dementia is the general term for a condition that leads to the unnatural loss of cognitive function as one ages. Symptoms of dementia include memory loss, confusion, difficulty speaking or expressing thoughts, impulsive behavior, loss of interest in activities, and hallucinations. While approximately one third of people aged 85 or older may have some form of dementia, it is an abnormal aging process.1 The four main diagnosable types of dementia are frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the focus of this paper. Forms of dementia can also coexist in a condition called mixed dementia.2 This paper discusses current AD research and the potential use of music therapy and music-based interventions to mitigate symptoms or even treat AD.

Frontotemporal dementia impacts cognition due to neuron damage in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. It is rare, mainly affecting people between the ages of 45 and 64.3 Lewy body dementia affects over a million Americans and is characterized by the buildup of alpha-synuclein protein deposits. These deposits, called Lewy bodies, lead to the loss of the neurotransmitters acetylcholine and dopamine. Symptoms include visual hallucinations, changes in focus, and cognitive decline.4 Vascular dementia is caused by damage to blood vessels in the brain, impeding blood and oxygen flow, and changes in the white matter of the brain. These changes, often visible on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, impact memory, cognition, and behavioral patterns.5 Researchers have recently discovered another type of dementia, limbic predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE), in brain autopsies, but are yet to diagnose the condition in a living person.1

Alzheimer’s Disease

As of 2022, 10.7% of the US population aged 65 or older, roughly 6.5 million people, suffer from AD.6 Once diagnosed with AD, patients have an average lifetime expectancy of four to eight years. However, the disease does not have a set course, and some might suffer from AD for up to 20 years. AD is a particular concern given the phenomenon of population aging: when the number of people 65 and older steadily increases relative to the number of people 64 and younger. This process is mainly due to a decrease in fertility as well as a reduction in mortality rates for the elderly. By 2030, a projected 74 million Americans will be 65 or older, meaning that roughly one in five Americans will be elderly. By 2060, a projected 13.8 million elderly people will have AD.7

AD research and awareness have substantially increased in the last forty years, and currently, AD is the seventh leading cause of death in the US. The number of recorded deaths from AD increased by 145.2% from 2000 to 2019. The cause for this increase is not only due to population aging, but also due to decreased death rates of other prevalent conditions in the elderly population, including heart disease and stroke, as well as the clinical advancements related to AD over the last twenty years.7

Onset and Progression of AD

The disease first appears in the lateral entorhinal cortex,8 a region of the brain central to learning and memory. After spreading through the cortex (the perirhinal cortex and posterior parietal cortex), the disease then spreads to the hippocampus–responsible for long-term memory formation. Degeneration first appears in the temporal and parietal lobes, the orbitofrontal cortex, and neocortical regions.9 One of the leading hypotheses about the cause of AD is the amyloid hypothesis, which proposes that AD is caused by the excessive buildup of the proteins amyloid beta (Aβ) and phosphorylated tau (tau), leading to neuron death and brain atrophy

The progression of AD involves several phases. The first phase, called the cellular phase, involves changes that can begin around 20 years before diagnosis (preclinical). During this phase of the disease, symptoms are not yet evident, but elevated Aβ and tau levels are detectable through positron emission tomography (PET) scans and cerebrospinal fluid tests. Aβ is a normal product of the breakdown of APP, a type I transmembrane protein found in tissues and organs throughout the body and the central nervous system. The enzymes β-secretase and γ-secretase

split APP into two peptide fragments: Aβ and soluble amyloid precursor protein (sAPP). Aβ, which is 37 to 49 amino acids long,10 is likely involved in neuron plasticity,11 repairing damage (including leaks in the blood-brain barrier), and maintaining synaptic activity.12 Imprecise γ-secretase cleavage of Aβ at the C terminus leads to the creation of Aβ42–the main component of amyloid plaques–and Aβ40. The relationship between these two isoforms plays an essential role in AD–an increased Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio serves as a catalyst for the disease.13 Aβ monomers can form into protofibrils, amyloid fibrils, and oligomers. Amyloid fibrils are large and insoluble, and can later form into senile plaques, a trademark characteristic of AD. Recent research suggests, however, that Aβ oligomers–smaller, soluble clumps of Aβ that spread throughout the brain–are more responsible for toxic changes in the brain that lead to cognitive decline.14 Changes in neurons, microglia, astroglia, neuroinflammation, vascular failure, and glymphatic dysfunction occur in tandem with the aggregation of Aβ. 15

Once the level of Aβ reaches a certain point, tau accumulation is triggered, and the microtubule-associated protein (MAP) tau begins to form into tangles.16 Tau, which has six isoforms, is normally responsible for stabilizing microtubules in neurons and maintaining the parallel structure of intracellular transport systems.17 Aβ causes increased tau protein kinase I (glycogen synthase kinase 3, or GSK3) activity, leading to increased phosphorylated tau. The phosphorylated tau then mostly likely undergoes conformational change and polymerization in order to form into paired helical filaments, which comprise the neurofibrillary tangles characteristic of AD. These tangles bind to metabolic proteins and might also sequester other MAPs, leading to cytoskeleton weakness and neuron death due to the loss of essential proteins.18

Figure 1. Hallmark characteristics of AD. This figure contrasts (a) a healthy brain with (b) a brain with severe AD, with the formation of tau tangles and Aβ plaques in individual neurons, and overall tissue shrinkage in the brain. Image (c) compares a model of a healthy brain with a brain with severe Alzheimer’s, demonstrating severe tissue loss. Image was adapted from [19, 20].

For many, the first symptoms of AD fall under the category of mild cognitive impairment, which occurs when brain damage due to the buildup of Aβ and tau overwhelms the brain to an extent that it can no longer function normally. Within the span of five years post-diagnosis, roughly a third of patients with mild cognitive impairment due to AD develop dementia.7 These first symptoms involve a decline in non-memory related cognition. The mild stage of the disease can cause wandering, lead to difficulty handling expenses, and personality shifts, including depression and apathy. The regions of the brain controlling reasoning, language, conscious thought, and sensory processing are damaged in the moderate phase of the disease, which leads to symptoms such as general confusion and memory decline, trouble recognizing people, inability to learn new skills, trouble with daily routines, hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia.19 This stage of the disease is normally the longest, lasting from 2-10 years. Late-stage AD, which can last from 1-5 years, is the final and most severe stage, during which patients can no longer live without significant assistance. At this point, brain tissue significantly shrinks, especially in the cortex, due to neuron breakdown from the spread of amyloid plaques and tau tangles.17 Patients struggle to communicate, lose most of their awareness, and become susceptible to infection.21

Risk Factors for AD

Age is the most significant risk factor for AD once one reaches the age of 65, the likelihood of developing AD doubles every five years,22 going from 5% at age 65 to 33.2% by age 85.7 Genetics also seems to play a role in the disease’s development. Around 1-6% of AD patients suffer from early-onset AD (EOAD), the form of the disease developed between the ages of 30 and 65. Most EOAD patients have familial AD, meaning that they have more than one family member in more than one generation with AD. The majority of these cases are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Mutations in the genes presenilin-1 (PSEN1) and presenilin-2 (PSEN2) increase the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio significantly, thus leading to increased Aβ accumulation and the onset of AD.20 Mutations in these genes almost guarantee the development of the disease, normally in the EOAD form.7, 23

The likelihood of developing late-onset AD (LOAD) also has a significant correlation to genetics; the risk of developing the Alzheimers is 60-80% related to heritable factors. Out of the thirty known mutations of the APP gene, twenty five are associated with AD and cause the increased accumulation of Aβ. The gene apolipoprotein E (APOE), on chromosome 19, has three isoforms; the APOEε4 allele can increase the risk of developing AD (both LOAD and EOAD) by 300 - 400%,15 while the APOEε2 allele is related to a lower risk of developing AD.20 Results based on racial and ethnic groups have also produced inconsistencies.7

Sex is another factor that affects one’s risk of developing AD, as women are more likely to develop AD than men. Around two-thirds of Americans with AD are women. This difference is likely due in part to the fact that women on average have a longer lifespan than men, thus leading to a greater lifetime likelihood of developing AD Women are also 1.7 times more likely

than men to have a high tau burden, and thus a heightened AD risk. The gene that codes for the enzyme ubiquitin-specific peptidase 11 (USP11) is located on X chromosomes. USP11 removes the protein tag ubiquitin, which marks proteins to be degraded, from certain proteins, including tau. The lack of ubiquitin allows these proteins to aggregate. USP11 is one of the roughly 10-20% of genes not affected by X inactivation, meaning that women have two copies of this gene, and thus have an increased likelihood of tau accumulation.24 Other factors contributing to the increased risk for women are still unclear, and studies currently have mixed results.

People with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) also face an elevated risk of AD because the APP gene is located on chromosome 21. This extra chromosome 21 in people with Down syndrome usually heightens the production of Aβ, often leading to EOAD. Around 30% of people in their 50s with Down syndrome AD, and close to 50% of people in their 60s with Down syndrome have AD.25

Environmental factors and comorbidities can also impact one’s risk for developing AD. Air pollution has been shown to damage one’s frontal cortex. Exposure leads to oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, increased Aβ42, and thus neurodegeneration. It is also linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Certain metals may also increase risk. For example, lead and cadmium can cross the blood-brain barrier and have been associated with heightened Aβ levels. For many years, it was believed that aluminum could cause AD, but concrete evidence for this theory is yet to emerge.

Diet is another important risk factor which researchers have recently begun to focus on while taking antioxidants, vitamins, polyphenols, and fish decrease AD risk, ingesting saturated fat and excess calories increases risk. The processing of these foods degrades crucial nutrients while producing toxic byproducts, like advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which can lead to oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neurological damage.20 Cardiovascular conditions increase the likelihood of the presentation of AD (due to Aβ and tau), but can be mitigated by a healthy diet, and regular exercise, among other factors.

Lifestyle interventions are key to reducing one’s risk of developing AD. An observational study involving 2765 participants evaluated five lifestyle factors that promote health: at least 2.5 hours of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, not smoking, the adoption of the Mediterranean-Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet, and the maintenance of intellectual engagement through late-life cognitive exercise. Researchers concluded that people who maintained two or three of the healthy lifestyle factors had a 37% decreased AD risk, and people who maintained four or five healthy lifestyle factors had a 60% decreased AD risk, compared to people who maintained none or only one of the healthy lifestyle factors.26, 27

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are also risk factors for AD. Mild TBI and AD both lead to cortical thinning, causing memory loss, decrease in verbal fluency, and decrease in information processing. Within the first year of experiencing a TBI, the likelihood of being diagnosed with dementia is four to six times higher than in people without TBI. However, TBI can impact dementia risk even 30 years after occurance. Seniors who experience moderate TBI throughout their lifetime (commonly due to sports like football, boxing, soccer, and hockey) have a 2.3 times greater risk than older adults who have never had TBI this risk is 4.5 times greater when the regular TBI are severe.28

Diagnosis of AD

Diagnosing AD is a multi-step process. Health care providers initially review patients’ medical history, including psychiatric, psychological, and family history, as well as medication information. Blood or urine samples are tested to rule out other conditions with similar symptoms to dementia, like thyroid issues and vitamin deficiencies.29 A mood test is conducted to rule out mental health disorders, like depression, that present similar symptoms. Neurological tests are then used to evaluate speech, coordination, balance, muscle tone, reflexes, and hearing. Cognitive, functional, and behavioral tests are used to assess memory, problem-solving skills, thinking ability, focus, and executive function. These tests are meant to evaluate whether cognitive limitations impact the patient on a daily basis or in a significant manner.

An emerging diagnostic tool is the assessment of specific biomarkers–such as Aβ, hyperphosphorylated tau, and neuronal injury–through brain imaging, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) taps, and blood tests. Biomarkers can be used to identify the disease in its early stages, and can be measured and standardized through highly precise automated assays.30

MRI scans or computed tomography (CT) scans can rule out tumors, strokes, fluid buildup, or other brain damage that might cause similar symptoms to AD. MRI scans, which use radio waves and have magnetic fields, can also be used to see if brain tissue has shrunk. MRI scans are preferred to CT scans (which generate cross-sectional images of the brain through X-rays) for the diagnosis of AD.30 PET scans use radioactive tracers to view specific areas of the brain; both amyloid and tau PET scans, which test for the abnormal burden of Aβ and tau, respectively, are used mainly in research settings. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG-PET) scans show areas of low glucose metabolization, a sign of dementia, and can be used to differentiate between frontotemporal dementia and AD.31 Amyloid PET scans, while able to detect the presence of AD, are unable to provide information about the severity of the disease and cognitive ability compared to tau PET scans and FDG-PET scans.32

CSF is the fluid that insulates, protects, and nourishes the brain and spinal cord. The three CSF biomarkers used to diagnose AD are Aβ42, phosphorylated tau (referred to as p-tau),

Figure 2. Brain PET sc low amyloid and tau and the middle and tau, but not at the threshold of AD. The image on the right depicts levels of amyloid and tau past the threshold of healthy, leading to an AD diagnosis.33and total tau (referred to as t-tau). Abnormal Aβ42 levels are detectable in the CSF before they are visible on amyloid PET scans. Typically, a 50% decrease in Aβ42 concentration is the level of Aβ42 that indicates AD, as it signifies that Aβ42 has accumulated in the functional tissue of the brain. However, Aβ42 CSF levels alone are not accurate enough to lead to a diagnosis of AD; a 200% increase of p-tau concentration and 300% increase of t-tau concentration also evidences AD.29 The CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio can also provide more information than levels alone Aβ42; Aβ40 is the most abundant amyloid peptide in CSF and does not show significant change during the development of AD, and can be used to reliably normalize Aβ42. The three main CSF biomarkers have shown a diagnostic sensitivity of 95% to predict AD in its prodromal phase and identify AD as opposed to regular mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and other dementias.34

While blood is a more accessible medium for biomarkers than CSF, which is accessed through a lumbar puncture, biomarkers exist in very low concentrations in blood, and plasma proteins are likely to interfere with their measurement. The Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in plasma has been shown to correlate with CSF and PET biomarkers, with a decrease of 14.3% in subjects with amyloidosis. Plasma levels of axonal neurofilament light (NFL) proteins also predict neurodegeneration, cognitive decline, and familial AD roughly 6.8 years before the onset of symptoms, but have a low specificity. Aβ42, p-tau, t-tau, and lactoferrin, have been proposed as possible AD biomarkers in saliva, a bodily fluid easily accessed through non-invasive procedure.31 Synapses and presynaptic proteins also have potential as biomarkers for AD. Unlike Aβ and tau, synaptic impairment and degeneration directly leads to cognitive impairment, and the measurement of levels of proteins such as the presynaptic vesicle proteins synaptotagmin and rab3a, the presynaptic membrane protein SNAP-25, and the dendritic protein neurogranin might be used to measure the effectiveness of potential AD drugs.

Current Treatments for AD

Most treatments developed for AD aim to treat the symptoms of the disease as opposed to modifying it. In the early stages of the disease, cholinesterase inhibitors, such as galantamine, rivastigmine, and donepezil, work to mitigate cognitive and behavioral decline.35 Current research has shown that this is most likely due to their prevention of the decomposition of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter chemical that affects muscle movement, normal body function, learning, memory, and focus.36 In later stages of the disease, patients are prescribed memantine, an N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist. People with AD disease have too much glutamate, a neurotransmitter which passes calcium to neurons, leading to excess calcium and an increased speed of cell death. Memantine blocks overactive NMDA receptors in order to decrease glutamate levels, and is used to slow decreases in quality of life for people with severe AD. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine can be used in tandem to slow cognitive decline.37

Out of the many trials of disease-modifying drugs currently in progress or development, two drugs aiming to reduce Aβ buildup have received widespread coverage. Aducanumab (Aduhelm) is an IgG1 monoclonal antibody administered through intravenous infusion that targets Aβ aggregates. In 2019, two highly similar clinical trials of Aduhelm that began in 2015 were halted after an independent monitor committee determined that the drug had no benefit.38 Biogen later concluded that in one of the trials, high Aduhelm dosage slowed cognitive decline, but only very slightly The Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB)

score is an outcome measure scored on a 18-point scale, with 6 sections of even weight used to measure the cognitive abilities and functions of drug trial participants. A score of 0.5 to 6 indicates an early stage of AD, with a higher score indicating a worse condition. Aduhelm participants had on average a score decrease of 0.39. 40% of trial participants developed swelling or bleeding in their brains, in some cases so severe that they ended their trial participation. A total of 6% of total participants of both trials dropped out of the trials before they were shut down.39 Despite these findings, Biogen met with the FDA to renew development of Aduhelm two months after the trials ended, ultimately leading to its accelerated approval in 2021, the first FDA approval of an AD drug since 2003. An 18- month investigation by the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the House Committee on Oversight and Reform concluded in late December of 2022 that the approval process for Aduhelm had been faulty.40 Biogen is also partially funding lecanemab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targets Aβ protofibrils sponsored by pharmaceutical company Eisai. The conclusions of the phase 3 trial were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in late November of 2022. On January 6th of 2023, the FDA approved lecanemab, or Leqembi, through the Accelerated Approval pathway.41 Enrolled in the trial were 1795 people with early AD between the ages of 50 and 90 with an average CDR-SB of 3.2. 898 participants received lecanemab and 897 received a placebo. The adjusted average difference from CDR-SB score at start was 1.21 among participants receiving lecanemab and 1.66 among participants receiving the placebo. 14% of the lecanemab recipients and 11.3% of the placebo recipients experienced serious adverse effects, most commonly infusion-related amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA). 12.6% of lecanemab recipients experienced edemas (ARIA-E) and 17.3% of lecanemab recipients experienced hemorrhaging (ARIA-H). 6.9% of lecanemab recipients discontinued the trial due to adverse reactions.42 While in recent years, disease-modifying drugs have demonstrated potential, their efficacy is questionable and their approval controversial.

Music-based Interventions in AD Care

Music, a cognitively stimulating activity, has shown potential in terms of both preventing and mitigating the effects of dementia. A twin study found that, after accounting for sex, education, and physical activity, musicians were 64% less likely than non-musicians to develop MCI or dementia. On cognitive assessments, musicians in general had a 29% higher likelihood than non-musicians of performing cognitively in or above the 90th percentile; and musicians who play frequently were found to have the best cognition, with an 80% higher likelihood than non-musicians of performing in or above the 90th percentile.43 This suggests that music can decrease one’s likelihood of developing dementia, and studies have shown that it can also benefit those who have dementia.

Music-based interventions (MBIs) have been used to alleviate symptoms of dementia, including cognition, mood, and sleep. One particular form of MBI is music therapy, which is the clinical and therapeutic application of music to accomplish individualized goals ranging from psychosocial development to physical rehabilitation. Music therapists use musical activities and interactions to foster interaction, enthusiasm, and confidence; the American Music Therapy Association listed some of their “healthcare and educational goals” as “promot[ing] wellness, manag[ing] stress, alleviat[ing] pain, express[ing] feelings, enhanc[ing] memory,” and “improv[ing] communication.”44 These activities can be receptive musical activities (listening to

music) or active musical activities (making music). Receptive music therapy is mainly used as a method of relaxation and as a form of reminiscence therapy, a therapeutic intervention for Alzheimer’s that uses prompts to discuss a patient’s past. Active music therapy is used to promote a positive mindset and an increase in the self-confidence of the patients.45 Currently, research on the efficacy of MBIs varies, with some studies reporting weak findings while others reporting positive outcomes relating to mood, sleep, cognition, and general quality of life.46 There are several different types of memory, with which music and AD have different and complex relationships. Memories can be characterized as either short-term or long-term. A key form of short-term memory is working memory, which is the momentary recollection of something during the duration of a task. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for short-term memory; in particular, based on MRIs, scientists believe that the left side of the prefrontal cortex is responsible for the verbal aspect of working memory while the right side controls spatial working memory. Long term memory falls into two broad categories: explicit memory, which is conscious recollection, and implicit, which is the unconscious influence of past experiences on one’s behavior. Explicit memory can be either episodic, which is the recollection of specific events, or semantic, which is the recollection of facts, definitions, and information. Episodic memories form in the hippocampus, with general knowledge information transferred from the hippocampus to the neocortex during sleep. The amygdala is responsible for maintaining the emotional significance of memories as well as generating new, fear-based memories, as clear from studies on patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety. Implicit memory can be procedural, which is the recollection of motor-related skills, or can be linked to priming, which is the connection of different concepts over time.47 The main regions of the brain associated with memory are the amygdala, the hippocampus, the cerebellum, and the prefrontal cortex. The basal ganglia are responsible for the coordination of motor skills, while the cerebellum is responsible for fine motor skills.48 Memories are formed through the reactivation of patterns of neurons, which happens due to synaptic plasticity, which are the changes that take place at synapses.49 Memories are initially fragile, but are strengthened through the process of memory consolidation.50 When a certain pathway experiences frequent reactivation, it is strengthened and has long-term potentiation.51 The ability for one to retain new knowledge peaks in one’s twenties.52 After that, the ability to remember new knowledge declines, with a loss of 5% of neurons in the hippocampus every decade.53 There are several different types and aspects of musical memory, and each of these systems relates to a different area of the brain. Episodic musical memory has been found to have some basis in the temporal cortex, the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices, the superior temporal sulcus, the superior temporal gyrus, and the auditory cortex.9 Musical memories, particularly implicit musical memories, have been found to be very well preserved even in the late stages of AD. Long-term musical memories were found to be encoded in the caudal anterior cingulate gyrus and the ventral pre-supplementary motor area. FDG-PET scans have shown that these regions of the brain do not experience severe cortical atrophy and disrupted glucose-metabolism. (These regions, however, have relatively similar levels of Aβ accumulation compared to the rest of the brain).9

Figure 3. Regions of the brain encoding long-term musical memories do not overlap with regions of damage from AD. Regions of the brain that encode long-term musical memories (outlined in white) experience minimal atrophy or hypermetabolism relating to AD. Warmer colors represent more significant brain damage due to AD 9

Materials and Methods

Research for this project was primarily conducted through a literature review using papers available on PubMed and Google Scholar. Key search terms included “Alzheimer’s,” “dementia,” “music therapy,” “music-based interventions,” “cognitive function,” “anxiety,” “depression,” “brain,” and “study.”

The second aspect of this project involved direct observations of group music therapy at the Memory Care Unit of the senior residence The Watermark at Brooklyn Heights, interviews with music therapists leading the sessions, and weekly flute performances of familiar tunes, folk songs, and popular music (like songs by The Beatles). The music therapists hold sessions once a week for 1.5 hours. Around 10 residents participate each week; there are some consistent participants but no fixed group. The goals are measured qualitatively, based on how people respond in situations over time. They can be broken up into four categories relating to the symptoms of AD. The questions asked to the music therapists were:

1. What is your music therapy training/background?

2. What are the goals of music therapy treatment for The Watermark residents?

3. What are the techniques that you use, and do you use any specific methods when working with AD/memory care patients?

4. How do you measure the progression of your patients?

5. What non-music techniques do you use in sessions?

NOTE: The Watermark at Brooklyn Heights is a very “cultivated” environment compared to other environments in which the music therapists have worked. It is a high-end facility, with ample space, peace, and attention given to each resident. In less advantaged communities, elderly members of the community have the option to attend a day habilitation/social adult daycare facility. At locations like these, there are often 20 to 50 people in a group, therapy sessions take

place in the open, without a quiet atmosphere, and often have the additional goal of providing a sense of peace and “focus” to the recipients.

Results and Discussion

Music Therapy and Cognitive Function

Studies on the effects of music therapy (with a trained music therapist) and MBIs (which can involve a variety of musical activities, sometimes integrated into therapeutic practices) are generally inconclusive because of the lack of standardization of methodology. Differences between studies include varying genres of music, levels of individualized music selection, types of interaction with recipients, and musical formats.45 Several studies and meta-analyses have reported weak or inconclusive results in support of music therapy in AD care, while others have produced positive results.46 A meta-analysis of four studies focused on the cognitive effects of music therapy in AD care found a mean effect size of 1.56 (with a confidence interval of 95%), where an effect size of 0.2 was small, an effect size between 0.2 and 0.6 was considered medium, and 0.6 and above was considered large.45 A study among 201 Japanese adults with MCI found that hour-long music-making groups over a period of 40 weeks led to an improvement in scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a cognitive function test that evaluates orientation, attention and concentration, memory, and language and motor skills. The highest possible score is 30, with a normal score being 25 or above and a score of 24 or below considered abnormally low. People who participated in the weekly musical instrument session had a mean change of .46 (standard deviation of 2.1) on the MMSE, compared to a mean change of -.36 (standard deviation of 2.3) in the control group.54 Another study, in Spain, which involved 42 patients with a mild to moderate form of dementia based on CDR scores, also used the MMSE to analyze change in cognitive function. In this study, participants attended twelve music therapy sessions (designed by two music therapists) that each lasted for 45 minutes and took place twice weekly over a period of 6 weeks. Patients with mild dementia began with a mean MMSE score of 18.33 (standard deviation of 5.84) and ended with a mean MMSE score of 22 (standard deviation of 4.64). Patients with moderate dementia had a mean MMSE score of 12.5 (standard deviation of 3.02) before the start of the study and ended with a mean score of 17.88 (standard deviation of 4.03). This study determined that its findings are in line with research on music’s activation of networks key to brain plasticity and right hemisphere pathways associated with communication and comprehension. However, it also highlighted the lack of evidence relating to long-term changes in cognitive improvement and the lack of an improvement in the functional dependence of patients.55 A study focused on people with MCI combining exercise therapy with movement music therapy using repetitive rhythmic motions found that this combination led to an increased task-related concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin, especially in the medial prefrontal cortex. Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) scores, which reflect frontal lobe function through the assessment of prefrontal-related tasks, also increased. Overall, this study found that the combination of exercise therapy and movement music therapy increased the functional connectivity of the prefrontal cortex, thus improving cognitive and executive function.56

Music Therapy and Behavioral/Psychological Effects

The effectiveness of music therapy to mitigate the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) has been assessed by several studies and meta-analyses. One systematic review found that out of 7 included studies, the majority found an improvement in mood and in anxiety, depression, or both.57 A meta-analysis found that depression showed minimal signs of reduction directly after music therapy, but decreased after 6 months, demonstrating the potential for music therapy to be used as a treatment for long-term depression associated with dementia.58 However, other studies have found positive results directly after treatment. A study analyzing the effects of 30 minute music therapy sessions twice a week for 6 weeks found an immediate and consistent improvement in depression, particularly in participants with mild and moderate forms of dementia.59 The study on music therapy based in Spain found an improvement in anxiety and depression based on patients’ Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores, and also found an improvement in anxiety based on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI).55 A study on the effects of singing and listening to music on BPSD over a period of ten weeks found that listening to music improves behavior related to dementia, like agitation and disinterest, while singing was shown to especially improve physical presentations of depression, like weight loss and low energy.60 Another study on individual, receptive music therapy involving validation in AD care found that between the 4th week and the 16th week of treatment, anxiety and depression decreased, a positive change that lasted for up to 8 weeks after the last session.62

While studies, meta-analyses, and reviews have concluded positive results in terms of cognition and BPSD, MBIs have not shown a significant impact on daily function. In the Spanish study, scores on the Barthel Index, which is used to determine an individual’s level of dependency by evaluating their ability to complete basic daily tasks, did not show marked improvement. They explained that the participants’ level of dependency was so severe that it likely would have only improved after significant cognitive and motor rehabilitation.55 Another

Figure 4. Changes in Neuropsychiatric Inventory scores within the groups (mild dementia and moderate dementia) before and after 6 weeks of consistent music therapy sessions, broken down by symptom.55

Figure 4. Changes in Neuropsychiatric Inventory scores within the groups (mild dementia and moderate dementia) before and after 6 weeks of consistent music therapy sessions, broken down by symptom.55

limiting factor in the research of music therapy is the lack of standardization in studies, such as differences in active music therapy vs. music listening, live vs. recorded music, selected vs. individual music, group vs. personal intervention, and classical/relaxation music vs. pop/native music.45 The lack of consistent practices in studies results in a lack of consensus on the effectiveness of music therapy in AD care.

Direct Observations

For this project, I interviewed two licensed music therapists who, as part of the music therapy program at the Brooklyn Conservatory of Music, lead group music therapy sessions in the Memory Care Unit of The Watermark at Brooklyn Heights. I observed several sessions led by each music therapist, and performed flute (mostly the Beatles, as well as other familiar tunes) for half an hour every week for several months. While I was unable to determine any change in anxiety and depression, I did notice an increase in verbal engagement throughout the music therapy sessions. Additionally, many of the songs in the music therapy sessions and several of the songs that I played on the flute prompted the entire group (normally around 8 people) to sing along loudly. While around one to two people fell asleep in each of the music therapy sessions, the majority of the group stayed engaged, playing simple rhythmic instruments and responding to prompts from the therapist. When I played the flute, independent of the music therapy sessions, the majority of the group would clap after each piece, and several would hum or sing quietly to the songs they knew. This behavior increased when the group was larger; several times, people fell asleep when the group was only two or three people. Almost the entire group would sing along loudly to classic tunes and folk songs like “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and “This Land is Your Land.” After speaking with the music therapists, I was able to develop an understanding of the goals of their sessions and the effects that music has on the participating residents of the Memory Care Unit, and have summarized my understandings and observations in Table 1.

Table 1. Goals outlined by two music therapists working in the Memory Care unit of The Watermark at Brooklyn Heights, a senior living facility. Music therapists hold sessions once a week for 1.5 hours. Around 10 residents participate each week; there are some consistent participants but no fixed group. The goals are measured qualitatively, based on how people respond in situations over time. They can be broken up into four categories relating to the symptoms of AD.

GOALS & OBSERVED PRACTICES

Goal: By playing familiar songs to the recipients and involving them in the music, music therapists seek to promote happy memories and enthusiasm

MEMORY (COGNITIVE FUNCTION)

Observations:

● Trivia questions about songs and musical matching games give participants the opportunity to interact and recall memories.

○ When singing White Christmas, the music therapist plays a recording of the song and asks participants who performed it. Afterwards, he shows them a picture of the singer, Bing Crosby

SPEECH (COGNITIVE FUNCTION)

○ For example, every week Participant B repeats stories about the history of Brooklyn and musicians like Barbra Streisand and Neil Diamond. This prompts others in the group to speak.

○ Participants respond to recordings familiar to them (like Frank Sinatra’s rendition of New York, New York and Harry Belifante’s recording of The Banana Boat Song)

● People are likely to remember songs from their childhood/adolescence because those years are very formative Precomposed songs revive memories, help recipients process experiences, and prompt conversations

○ When I play Take Me Out to the Ball Game on the flute, everyone sings along.

○ When singing familiar songs like Jingle Bells, music therapists are silent during some verses to allow the participants to remember the lyrics themselves.

Goal: Through song, the music therapists seek to prompt speaking/interaction

Observations:

● The music therapists observe differences between sessions including that people who were catatonic and people with impaired speech begin to sing.

● Participants focus on the rhythm of the song and the chords when singing

Goal: By providing recipients with accessible and easy instruments, music therapists seek to promote movement and encourage excitement about the music, without recipients feeling like there is a risk of failure

Observations:

● People say, “I don’t have musical talent/background,” and have memories of music being something they quit. Because of this, music therapists pick instruments where people can be successful.

PHYSICAL

○ Tung drums (metal drums): in the key of c, which is often the most familiar key to people Music therapists sometimes transpose songs into the key of c to match the drums They are easy to play and there is no such thing as a wrong note

○ Shaker eggs: non-intimidating, lightweight.

● Physical reactions: people dance, stationary people move to beat, even with complicated rhythms and counter rhythms. Other reactions: closed eyes and tilted heads, facial expressions (dementia patients normally have slack facial expression)

● At the end of the session, one of the music therapists leads an exercise: shaking out hands, rolling out shoulders, moving heads side to side, taking deep breaths

Goal: By recreating precomposed songs with recipients, music therapists seek to stimulate social interaction, bring people into conversations, and create exchanges between recipients Music therapy supports emotional awareness, intragroup awareness, community building, and open discussions.

Observations:

● Promote socialization (music therapists don’t tend to interrupt conversations).

SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

● Try to steer things back to the music, especially when recipients are distressed (for example, when Participant A was getting used to moving into The Watermark)

● Conflicts are pretty mild At other facilities, people with dementia and mental health issues may have much bigger and more physical conflicts

● Music leads to smiles, looks of surprise, and the act of recognizing people around them. It can cut through the isolation often experienced by people with dementia. Involving dementia patients in the community around them can reduce the feeling dementia patients have of being stuck in their own heads

Neurobiological basis for MBIs for AD patients

Music and MBIs are connected to several neurobiological processes that might support their use as a therapeutic modality for AD patients. A study on the preservation of musical memory in AD patients examined blood oxygen level-dependent activations on functional MRI (fMRI) scans of healthy, young controls, analyzing the areas of the brain active during long-familiar songs, recently-heard songs, and unfamiliar songs. Researchers compared these to scans from probable AD patients (with positive Aβ and neurodegeneration biomarkers), and analyzed the scans for cortical atrophy, hypermetabolism, and Aβ deposits. Cortical atrophy and hypermetabolism related to AD had extremely minimal effects on the caudal anterior cingulate gyrus and the ventral pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA), regions of the brain found to encode implicit long-term musical memory.

MBIs are also viewed as effective mediums for clinical treatment because they engage patients, possibly due to the connection between auditory and reward networks, which lasts through the prodromal and MCI stage of AD. Positive reception of music from the superior temporal gyrus, an auditory region, leads to activity in the reward-related areas of the dopaminergic network, including the caudate, nucleus accumbens, insula, and amygdala. The connections between the auditory networks and reward networks are both functional and structural. Listening to familiar music leads to activity in regions of the brain related to reward circuitry, emotional processing, and auditory prediction (like the anterior cingulate cortex). One study proposed that this link could be used to change the behavior and increase motivation in AD patients, particularly through the use of MBIs with individualized music selections, which have been shown to be more efficacious than generalized practices.46

Music holds potential as a therapeutic modality for AD, especially when addressing problems relating to quality of life. These benefits can range from improvements in BPSD, interactions and social engagement, and the stimulation of long-term memories related to music. Additionally, the apparent preservation of implicit, long-term musical memories in AD suggests that music is an effective stimulant for AD patients. An appealing aspect of MBIs is that they are non-invasive and non-pharmacological, reducing the likelihood of negative side-effects, and easily adaptable to patients’ individual needs. Most studies, reviews, and meta-analyses suggest that there are little downsides to the incorporation of MBIs in an AD patients’ routine. Additionally, MBIs range from active music therapy, led by a professionally-trained music therapist, to receptive interactions with music through recordings, making the modality easily accessible. Research on the efficacy of MBIs, however, is still generally inconclusive, due to the lack of standardization of practices between studies. As a disease-modifying treatment, MBIs have also not shown significant efficacy in terms of improving the dependency and functionality of AD patients. While MBIs show promise as a measure to improve the quality of life of AD patients, on their own, they have not demonstrated significant potential to modify the course of the disease.

Developing Treatments for AD Involving MBIs

Despite the fact that MBIs might not be significantly and demonstrably efficacious on their own, a recent study combining non-invasive Gamma-frequency sensory stimulation with MBIs in animal models suggests that this combined treatment could lead to neurological and behavioral improvements. Researchers found that sensory (auditory and visual) stimulation at the frequency of 40 Hertz (Hz), corresponding with the Gamma rhythm in the brain, reduced

AD biomarker levels and improved cognitive and behavioral function in animal models of AD. In AD, the accumulation of Aβ disrupts neurons and decreases neuron synchronization, altering frequency bands in the brain (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Theta). The Gamma rhythm, a band of neural oscillation between 30-100 Hz sparked by “excitatory and fast-spiking inhibitory neurons,” is related to cognition, memory processes like encoding and retrieval, as well as short-term, working, and episodic memory.46 Some research has shown that irregular Gamma rhythm precedes and relates to Aβ accumulation, with both of these processes leading to further development of AD. Gamma-frequency optogenetic stimulation and Gamma-frequency visual stimulation have been shown to correct Gamma rhythm, reducing AD biomarkers and improving cognition.46 A study using mice with reduced and irregular hippocampus gamma rhythms (due to Aβ accumulation) found that Gamma-frequency optogenetic stimulation at 40Hz corrected the rhythm and reduced Aβ by around 50%. Stimulation led to the activation of microglia, which then cleared the Aβ aggregates.62 Another study on Gamma-frequency auditory stimulation over seven days using mouse models of AD found that the stimulation restored the Gamma rhythm, decreased Aβ deposits in the hippocampus and auditory cortex, and led to an increased functionality of the recognition and spatial memories of the mice.46 Music has potential in this sector, as both “natural music” and “rhythmic auditory stimuli” increase Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Theta frequency band activities. In particular, the musical meter of natural music corresponds with the frequency bands of Delta, and, at faster paces, Theta. Natural music, as well as auditory and acoustic rhythm, have also been shown to stimulate Beta and Gamma rhythms; during natural music, Beta activity increases, while high-Gamma activity changes depending on intensity and volume.46

The incorporation of Gamma-frequency stimulation into MBIs has the potential to correct Gamma rhythm and improve AD biomarker levels, neuronal and synaptic loss, and behavioral and cognitive function. There are still challenges involving the incorporation of Gamma-frequency stimulation into MBIs, including the fact that 40Hz is considered an unpleasant sound, and could be difficult to include in the practices of MBIs, which already involve sound. While research on this potential combined treatment, the effects of music on frequency activity, and the efficacy of Gamma-frequency stimulation in humans, is currently limited, these recent studies suggest that music does have future potential in the direct treatment of AD.46

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, July 2). What Is Dementia? Symptoms, Types, and Diagnosis. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved October 30, 2022, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-is-dementia.

2. Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). Mixed Dementia. Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia. Retrieved October 30, 2022, from https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/types-of-dementia/mixed-dementia.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, July 30). What Are Frontotemporal Disorders? Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved October 30, 2022, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-frontotemporal-disorders.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, July 29). What Is Lewy Body Dementia? Causes, Symptoms, and Treatments. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved October 30, 2022, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-lewy-body-dementia-causes-symptoms-and-treatments.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, November 1). Vascular dementia: Causes, symptoms, and treatments. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved October 30, 2022, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/vascular-dementia.

6. Alzheimer's Association. (2022). Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures.

7. Gaugler, J., James, B., Johnson, T., Reimer, J., Solis, M., Weuve, J., Buckley, R F., & Hohman, T J (2022). 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures - Alzheimer's Association. Alzheimer's Association. Retrieved November 5, 2022, from https://alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-infographic.pdf

8. Columbia University. (2013, December 22). Study Shows Where Alzheimer's Starts and How it Spreads. Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from https://www.cuimc.columbia.edu/news/study-shows-where-alzheimers-starts-and-how-it-spreads.

9. Jacobsen, J -H., Stelzer, J., Fritz, T H., Chételat, G., La Joie, R., & Turner, R (2015). Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Brain, 138(8), 2438–2450. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv135

10. Chen, G., Xu, T., Yan, Y., Zhou, Y., Jiang, Y., Melcher, K., & Xu, H. E. (2017, July 17). Amyloid beta: Structure, biology and structure-based therapeutic development. Nature News. Retrieved November 15, 2022, from https://www.nature.com/articles/aps201728.

11. U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2022). APP Gene: MedlinePlus Genetics. MedlinePlus. Retrieved November 14, 2022, from https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/app/.

12. Brothers, H. M., Gosztyla, M. L., & Robinson, S. R (2018, April 25). The Physiological Roles of Amyloid-β Peptide Hint at New Ways to Treat Alzheimer's Disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. Retrieved November 15, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5996906/.

13. Gu, L., & Guo, Z. (2013, August). Alzheimer's AΒ42 and AΒ40 peptides form interlaced amyloid fibrils. Journal of neurochemistry Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3716832/#:~:text=The%20imprecise%20cleavage,in%2n.d.%20brain.

14. Sengupta, U., Nilson, A. N., & Kayed, R. (2016, April). The Role of Amyloid-β Oligomers in Toxicity, Propagation, and Immunotherapy. EBioMedicine. Retrieved November 15, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4856795/.

15. Scheltens, P., De Strooper, B., Kivipelto, M., Holstege, H., Chételat, G., Teunissen, C. E., Cummings, J., & van der Flier, W M. (2021). Alzheimer's disease. Lancet (London, England), 397(10284), 1577–1590. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32205-4.

16. National Institute on Aging. (2017, August 23). How Alzheimer's Changes the Brain. YouTube. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://youtu.be/0GXv3mHs9AU.

17. Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). Brain Tour Part 2. Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/brain_tour_part_2.

18. Avila, J., Centro de Biología Molecular “Severo Ochoa” (CSIC-UAM), Lucas, J J., Pérez, M., Hernández, F., Address for reprint requests and other correspondence: J Avila, Zhu, B., & Mehler, M. F (2004, April 1). Role of Tau Protein in Both Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Physiological Reviews. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/physrev.00024.2003?rfr_dat=cr_pub%2B%2B0pubmed&url_ver=Z39. 88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org#:~:text=tau%20aggregates%20are,of%20synaptic%20contacts.

19. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, July 8). Alzheimer's Disease Fact Sheet. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved October 30, 2022, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet.

20. Breijyeh, Z., & Karaman, R (2020, December 8). Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer's Disease: Causes and Treatment. MDPI. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/25/24/5789.

21. Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). Stages of Alzheimer's. Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/stages.

22. NHS. (2021, July 5). Causes - Alzheimer's disease. NHS choices. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alzheimers-disease/causes/.

23. Bateman, R J., Aisen, P S., De Strooper, B., Fox, N. C., Lemere, C. A., Ringman, J M., Salloway, S., Sperling, R A., Windisch, M., & Xiong, C. (2011, January 6). Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer's Disease: A Review and Proposal for the Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimer's research & therapy Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3109410/.

24. Mayer, B. A. (2022, October 7). This May Be The Reason Why Women Are At Greater Risk Of Alzheimer's. Healthline. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://www.healthline.com/health-news/this-may-be-the-reason-why-women-are-at-greater-risk-of-alzheimers.

25. Alzheimer's Disease & Down Syndrome. National Down Syndrome Society (NDSS). (n.d.). Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://ndss.org/resources/alzheimers.

26. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020, June 17). Combination of Healthy Lifestyle Traits may Substantially Reduce Alzheimer's. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/combination-healthy-lifestyle-traits-may-substantially-reduce-alzhei mers.

27. Bhatti, G. K., Reddy, A. P., Reddy, P. H., & Bhatti, J. S. (2020, January 10). Lifestyle Modifications and Nutritional Interventions in Aging-Associated Cognitive Decline and Alzheimer's Disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6966236/.

28. Traumatic brain injury (TBI). Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia. (n.d.). Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/related_conditions/traumatic-brain-injury

29. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2022, February 19). Alzheimer's disease. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350453.

30. Khoury, R., & Ghossoub, E. (2019, November 13). Diagnostic Biomarkers of Alzheimer's Disease: A state-of-the-art review ScienceDirect. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S266614461930005X?via%3Dihub.

31. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). How Biomarkers Help Diagnose Dementia. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/how-biomarkers-help-diagnose-dementia.

32. Yang, B. S. (2012, January 23). Lifelong Brain-stimulating Habits Linked to Lower Alzheimer's Protein Levels. Lifelong brain-stimulating habits linked to lower Alzheimer's protein levels | Research UC Berkeley. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://vcresearch.berkeley.edu/news/lifelong-brain-stimulating-habits-linked-lower-alzheimers-protein-levels.

33. Yang, S. (2016, April 11). PET Scans Reveal Key Details of Alzheimer's Protein Growth in Aging Brains Berkeley News. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://news.berkeley.edu/2016/03/02/pet-scans-alzheimers-tau-amyloid/

34. Zetterberg, H., & Blennow, K. (2018, July 26). Biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease: current status and prospects for the future. Wiley Online Library Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://onlinelibrary wiley.com/doi/10.1111/joim.12816.

35. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). How is Alzheimer's Disease Treated? National Institute on Aging. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/how-alzheimers-disease-treated.

36. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (n.d.). Acetylcholine. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/science/acetylcholine

37. WebMD (n.d.). NMDA Receptor Antagonists and Alzheimer's. WebMD Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www webmd.com/alzheimers/guide/nmda-receptor-antagonists#:~:text=NMDA%20(short%20for%20N%2Dm ethyl,drugs%20may%20slow%20it%20down.

38. Johnson, M. (2022, December 29). House Investigation Faults FDA, Biogen for Alzheimer's Drug Approval. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2022/12/29/alzheimers-fda-biogen-aduhelm/.

39. Belluck, P (2021, July 14). Cleveland Clinic and Mount Sinai won't administer Aduhelm to Patients. The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/14/health/cleveland-clinic-aduhelm.html.

40. Belluck, P (2022, December 29). Congressional Inquiry into Alzheimer's Drug Faults its Maker and F.D A The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/29/health/alzheimers-drug-aduhelm-biogen.html.

41. Commissioner, O. of the. (n.d.). FDA Grants Accelerated Approval for Alzheimer's Disease Treatment. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-alzheimers-disease-treatm ent.

42. van Dyck, C. H., Swanson, C. J., Aisen, P., Bateman, R J., Chen, C., Gee, M., Kanekiyo, M., Li, D., Reyderman, L., Cohen, S., Froelich, L., Katayama, S., Sabbagh, M., Vellas, B., Watson, D., Dhadda, S., Irizarry, M., Kramer, L. D., & Iwatsubo, T (2023). Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2212948

43. Walsh, S., & Brayne, C. E. (2021). Does playing a musical instrument prevent dementia? Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 17(S10). https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.049684

44. American Music Therapy Association (AMTA). (2005). What is Music Therapy?. American Music Therapy Association. https://www.musictherapy.org/

45. Vasionytė, I., & Madison, G. (2013). Musical intervention for patients with dementia: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(9–10), 1203–1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12166

46. Tichko, P., Kim, J C., Large, E., & Loui, P (2020). Integrating music-based interventions with gamma-frequency stimulation: Implications for healthy ageing. European Journal of Neuroscience, 55(11–12), 3303–3323. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15059

47. The University of Queensland. (2022, August 31). Types of Memory Queensland Brain Institute. Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://qbi.uq.edu.au/brain-basics/memory/types-memory

48. The University of Queensland. (2018, July 23). Where Are Memories Stored in the Brain? Queensland Brain Institute. Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://qbi.uq.edu.au/brain-basics/memory/where-are-memories-stored

49. The University of Queensland. (2018, July 23). How Are Memories Formed? Queensland Brain Institute. Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://qbi.uq.edu.au/brain-basics/memory/how-are-memories-formed

50. Bisaz, R., Travaglia, A., & Alberini, C. M. (2014, October 3). The Neurobiological Bases of Memory Formation: From Physiological Conditions to Psychopathology Psychopathology Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4246028/

51. The University of Queensland. (2018, July 23). How Are Memories Formed? Queensland Brain Institute. Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://qbi.uq.edu.au/brain-basics/memory/how-are-memories-formed

52. The University of Queensland. (2018, July 23). Memory and Age. Queensland Brain Institute Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://qbi.uq.edu.au/brain-basics/memory/memory-and-age

53. Young, C. (2015, September 24). How Memories Form and How We Lose Them. YouTube. Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://www youtube.com/watch?v=yOgAbKJGrTA

54. Doi, T., Verghese, J., Makizako, H., Tsutsumimoto, K., Hotta, R., Nakakubo, S., Suzuki, T., & Shimada, H. (2017). Effects of cognitive leisure activity on cognition in mild cognitive impairment: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(8), 686–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.013

55. Gómez Gallego, M., & Gómez García, J (2017). Music therapy and Alzheimer's disease: Cognitive, psychological, and behavioral effects. Neurología (English Edition), 32(5), 300–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrleng.2015.12.001

56. Shimizu, N., Umemura, T., Matsunaga, M., & Hirai, T (2017). Effects of movement music therapy with a percussion instrument on physical and frontal lobe function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Aging & Mental Health, 22(12), 1614–1626. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1379048