Leading With Purpose and Heart

A

Conversation With Cassandra Bradby, MD

2025 –2026 SAEM BOARD OF DIRECTORS

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS

SAEM President

Emory University School of Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Bylaws Committee

• Governance Committee

• Ethics Committee

Jody A. Vogel, MD, MSc, MSW

SAEM President-Elect

Stanford University

Board Liaison to:

• RAMS Board

• Committee of Academy Leaders

• SAEM Federal Funding Committee

• Nominating Committee

• Sex and Gender in Emergency Medicine Interest Group

Pooja Agrawal, MD, MPH

Member at Large Yale Department of Emergency Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine

• ED Administration and Clinical Operations Committee

• Grants Committee

• Behavioral and Psychological Interest Group

• Pediatric Emergency Medicine Interest Group

Bryn Mumma, MD, MAS

Member at Large

University of California, Davis

Board Liaison to:

• Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine

• Research Committee

• Disaster Medicine Interest Group

• Palliative Medicine Interest Group

• Research Directors Interest Group

• Trauma Interest Group

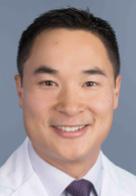

Cassandra Bradby, MD Member at Large East Carolina University

Board Liaison to:

• Academy of Emergency Ultrasound

• Awards Committee

• Critical Care Interest Group

• Oncologic Emergencies Interest Group

• Toxicology/Addiction Medicine Interest Group

Jane H. Brice, MD, MPH Chair Member University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Faculty Development Committee

• Vice Chairs Interest Group

Ava E. Pierce, MD

SAEM Secretary-Treasurer

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Board Liaison to:

• Global Emergency Medicine Academy

• Finance Committee

• Program Committee

• Clinical Researchers United Exchange Interest Group

• Wilderness Medicine Interest Group

Jeffrey P. Druck, MD

Member at Large

The University of Utah

Board Liaison to:

• Academy for Diversity & Inclusion in Emergency Medicine

• Fellowship Approval Committee

• Climate Change and Health Interest Group

• Evidence-Based Healthcare & Implementation Interest Group

• Tactical and Law Enforcement Interest Group

Patricia Hernandez, MD Resident Member

Massachusetts General Hospital

Board Liaison to:

• Wellness Committee

• Innovation Interest Group

• Neurologic Emergency Medicine Interest Group,

• Telehealth Interest Group

Ryan LaFollette, MD Member at Large University of Cincinnati

Board Liaison to:

• Simulation Academy

• Education Committee

• Airway Interest Group

• Operations Interest Group

• Transmissible Infectious Diseases Interest Group

Ali S. Raja, MD, DBA, MPH

SAEM Immediate Past President

Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School

Board Liaison to:

• Academy of Administrators in Academic Emergency Medicine

• Workforce Committee

• Educational Research Interest Group

• Informatics, Data Science, and Artificial Intelligence Interest Group

• Quality and Patient Safety Interest Group

Nicholas M. Mohr, MD, MS Member at Large University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Academy of Emergency Medicine Pharmacists

• Academy of Geriatric Emergency Medicine

• SAEM Federal Funding Committee

• Membership Committee

• Emergency Medical Services Interest Group

Megan Schagrin, MBA, CAE, CFRE

SAEM Chief Executive Officer

Liaison to:

• SAEM Executive Committee

• Association of Academic Chairs of Emergency Medicine (AACEM)

• RAMS Board

• SAEM Foundation

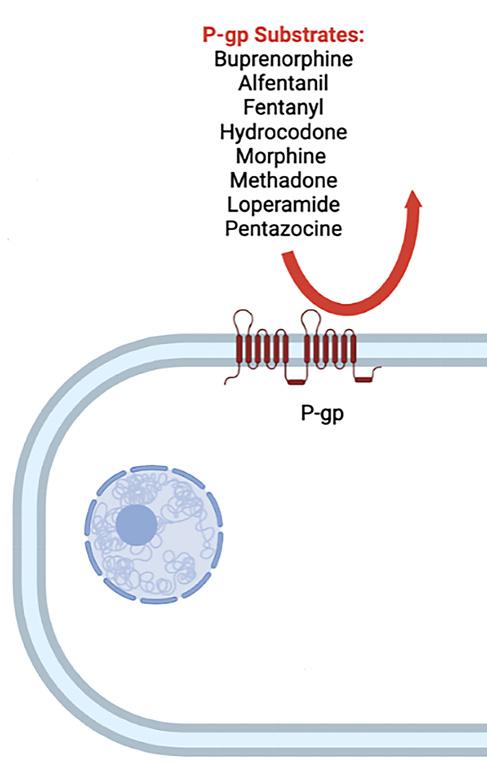

Loperamide Toxicity in the Era of Opioid Misuse

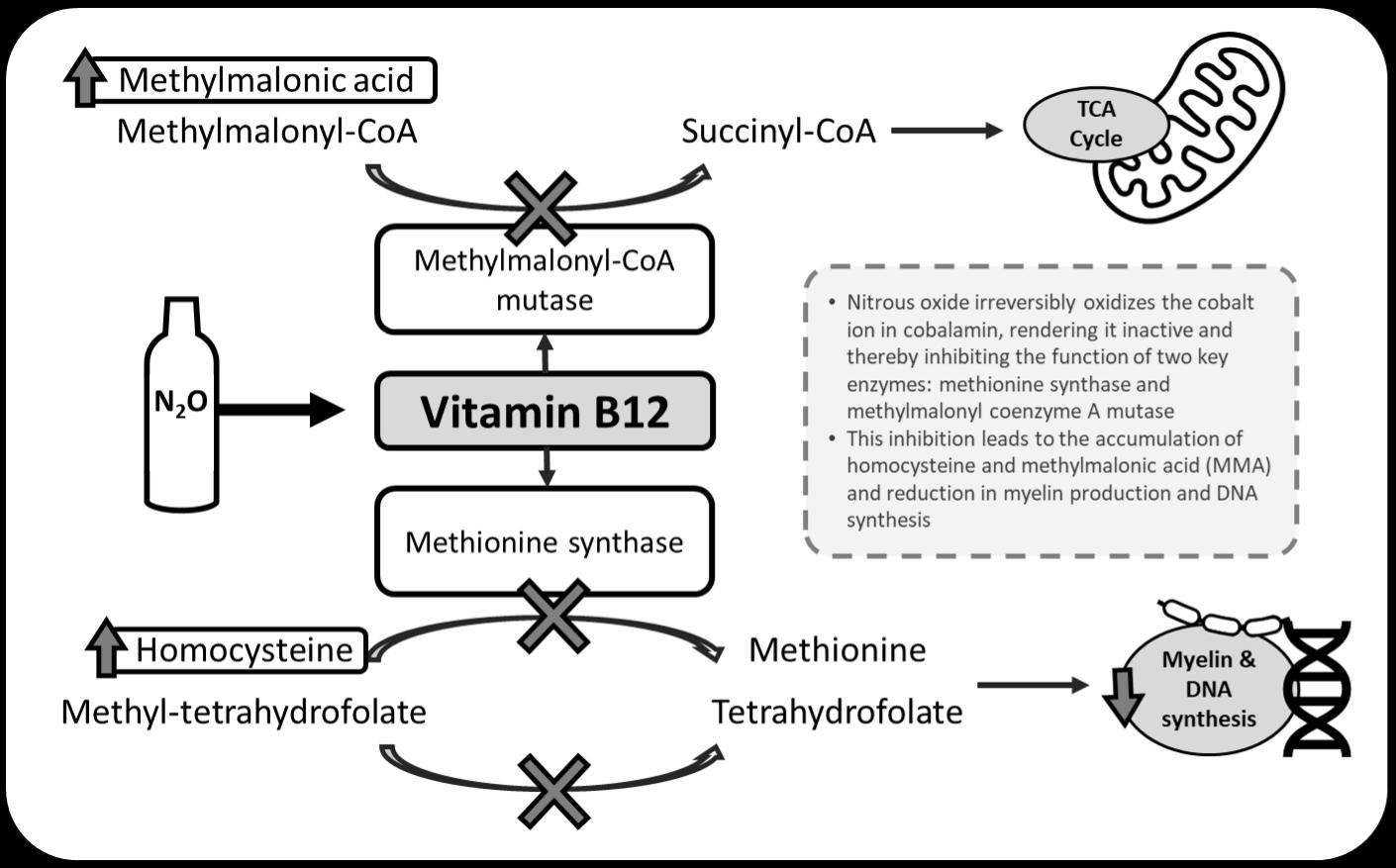

Hidden Dangers of Nitrous Oxide Abuse: What to KN2OW

Clerkship Myths: What You Need to Know, Part 2 — The Truth About Interviews

Your Focus: Deciding Whether Fellowship

for

in

Family Planning Meets Residency: Infertility and Parenthood in Emergency Medicine

in Avalanche

A Season of Momentum and Connection at SAEM PRESIDENT’S COMMENTS

Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS

Emory University 2025-2026 President, SAEM

As the seasons change, so too does the momentum of our work at SAEM. This fall, your board of directors gathered for an intensive two-day meeting to chart important priorities for the coming year. I’m excited to share highlights of our work and ways you can get involved.

Collaboration Across Emergency Medicine

In October, SAEM sent representatives to the All EM AI Summit, ensuring that our voice is part of national conversations on the role of artificial intelligence in emergency care. I also attended ACEP on behalf of SAEM, participating in the Council Meeting and in meetings with leaders from across emergency medicine organizations. These collaborations are vital as we strengthen our collective influence on the future of emergency medicine.

Building Connection and Engagement

One of our priorities is enhancing the ways you connect with each other and with SAEM. We are exploring multiple new avenues to improve your communication experience with the organization and other members, including updates to our website and community platforms designed to

make it easier to share ideas, resources, and opportunities.

Spotlight on SAEM Courses

Our educational programs remain one of the society’s crown jewels. If you haven’t yet participated in a course, now is the perfect time to explore how they can become part of your professional journey.

• Advanced Research Methodology Evaluation and Design (ARMED): Since 2017, 214 participants have advanced their careers through this ninemonth curriculum, which includes webinars, workshops, and mentoring.

• Emerging Leader Development Program (eLEAD): A yearlong leadership development program fostering foundational skills and networks for midcareer faculty. Now entering its fifth year, eLEAD has already supported 68 participants.

• Certificate in Academic Emergency Medicine Administration (CAEMA): Our certificate program for academic emergency medicine administrators, now training its fifth cohort, continues to grow in impact.

“As we look ahead, I encourage you to explore a course, engage in group, or academy, and connect with other members.”

• Advanced Research Methodology Evaluation and Design: Medical Education (ARMED MedEd): Focused on medical education scholarship, this program connects participants with mentors and provides training in grant writing, with 74 participants to date.

• Chair Development Program (CDP): Entering its thirteenth year with the largest cohort to date, the CDP prepares new, interim, and aspiring academic EM Chairs through a series of in-person and virtual lectures and networking opportunities.

Strategic Visioning

At our board meeting, we also devoted time to strategic planning in medical education, research, and professional development. With input from thought leaders across SAEM, we brainstormed new strategies to achieve our objectives.

Our Greatest Strength

Finally, a heartfelt thank-you to the SAEM staff. Their tireless dedication and behind-the-scenes work make our society’s progress possible.

As we look ahead, I encourage you to explore a course, engage in a committee, interest group, or academy, and connect with other members. Together, we are building a stronger, more connected, and more impactful SAEM.

ABOUT DR. LALL: Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS, is professor and vice chair of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine.

in a committee, interest members.”

SAEM Educational Courses: Which One is Right for You?

SPOTLIGHT

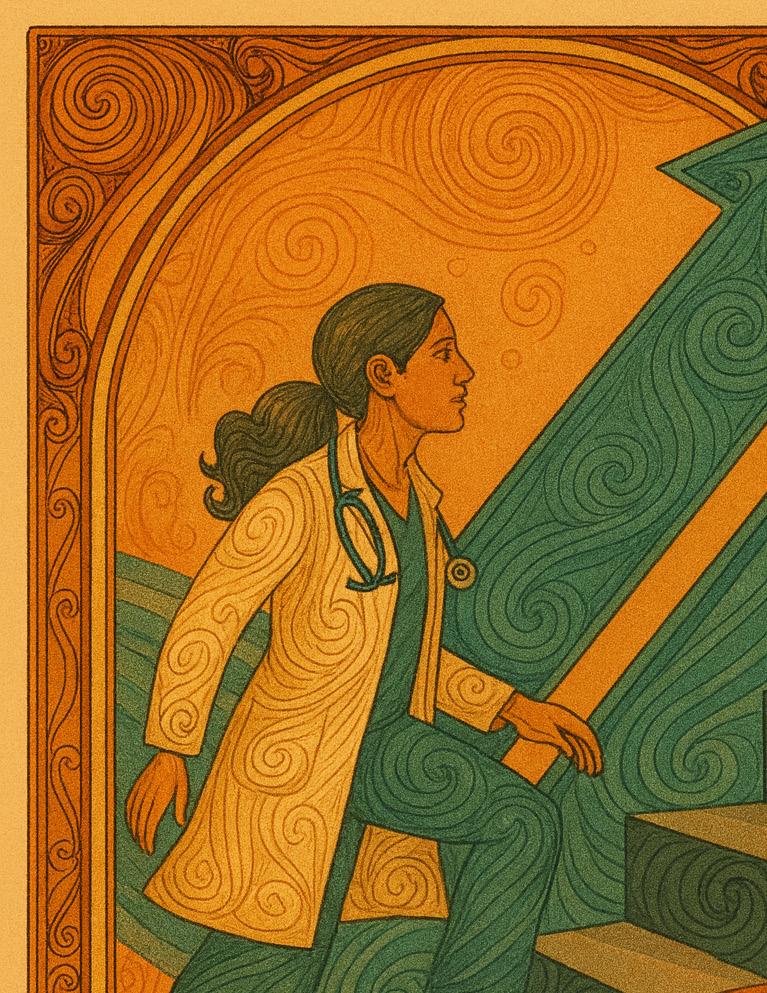

Leading With Purpose and Heart

A Conversation With Cassandra Bradby, MD

Cassandra Bradby, MD, is an associate professor and residency program director in the department of emergency medicine at the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University and ECU Health Medical Center. In September 2025, she also became assistant dean of graduate medical education, expanding her leadership in medical education and training.

She earned her undergraduate degree in biology from the College of William & Mary and her medical degree from Meharry Medical College. She completed her emergency medicine residency at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University and Kings County Hospital, where she served as education chief resident during her final year.

Dr. Bradby’s academic interests center on medical education, with a focus on recruitment, retention, and the impact of diversity, equity, and inclusion. She was a contributing participant in the 2022 Consensus Conference on Developing a Research Agenda for Addressing Racism in Emergency Medicine.

An active member of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine since 2014, Dr. Bradby has held several leadership roles, particularly within the Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine. She has served on the academy’s executive board since 2019 in multiple positions, including member-at-large, secretarytreasurer, president-elect, president, and immediate past president. She currently serves as a member-at-large on the SAEM Board of Directors.

Dr. Bradby speaking at the ECU SNMA Andrew A Best Banquet.

From biology at William & Mary to medical school at Meharry—what inspired you early on to pursue emergency medicine, and how have those experiences shaped your approach to leading a residency?

My journey toward emergency medicine started long before medical school. In high school, I was fortunate to have mentors in academic family medicine who encouraged me to explore opportunities and even took me on a college tour at William & Mary, which inspired me to pursue my undergraduate education there. One of those opportunities led me to serve as a scribe in the emergency department — my first real exposure to emergency medicine — and I was instantly captivated.

Their guidance also instilled in me a desire to give back, which I carried into medical school as a tutor in the basic sciences and as president of the Emergency Medicine Interest Group. By the time I graduated, I knew academic medicine was my path. Now, as a residency director, I try to honor that early mentorship by supporting and encouraging junior learners, remembering how meaningful it can be to have someone believe in you.

Your emergency medicine training at SUNY Downstate and Kings County concluded with you as Education Chief Resident. In what ways did that leadership role influence your career ambitions and leadership style?

My first SAEM Annual Meeting was during my time as chief resident, when we attended the Chief Resident Forum to network and learn best practices for the role.

That experience not only introduced me to SAEM but also opened my eyes to the wealth of opportunities within the organization.

Serving as chief resident was my first real lesson in leadership — and in middle management. It taught me how to negotiate, advocate for my peers, and, most importantly, communicate effectively. I learned that people often just want to feel heard and valued, and that communication is the foundation of good leadership. The role also gave me a preview of what it means to be an assistant program director — coordinating lecture schedules, working with speakers, and developing curriculum — so when I stepped into formal residency leadership, I was able to hit the ground running.

You’ve focused considerably on medical education— particularly recruitment, retention, and the impact of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Can you share a story or project that illustrates your biggest challenge or proudest success in this area?

Over the past 10 years in residency education, I’ve had the privilege of mentoring students and residents from across the country and around the world. My proudest successes are seeing them grow into the emergency physicians they aspired to be.

For example, mentees like Daniel Jourdan went on to become SAEM Residents and Medical Students (RAMS)

continued on Page 8

Dr. Bradby traveling to Munich with her family.

Dr. Bradby and her fiance, Terrance Hale, taking a walk in the Outer Banks

president, and Italo Brown is now the chief impact officer of T.R.A.P. Medicine. I know they would have achieved great things regardless, but it warms my heart to know I may have helped a little along the way.

The 2022 Consensus Conference on Addressing Racism in Emergency Medicine marked a key milestone. What lasting lessons and strategies emerged from that meeting, and how are you putting them into practice?

The 2022 Consensus Conference on Addressing Racism in Emergency Medicine highlighted how much of what we “know” is anecdotal, underscoring the urgent need for rigorous, evidence-based strategies. Key recommendations included prioritizing research on structural interventions, tracking equity metrics, and ensuring accountability in patient outcomes and institutional practices.

In my work, I aim to support multicenter collaborations, mentorship pathways for underrepresented scholars, and funding for research that tests interventions to reduce disparities. The goal is to move beyond best-practice assumptions toward strategies that are reproducible, scalable, and truly improve equity in emergency care.

As Residency Program Director at Brody School of Medicine, what innovations in curriculum or training have you introduced—especially around DEI, rare high-stakes procedures, or addressing imposter syndrome?

Recognizing that many of these challenges stem from soft skills, we took our curriculum “back to the basics” this year. During intern orientation, residents completed an observed history and physical with direct feedback from both a standardized patient and an attending,

including communication of the plan of care. We also added skills stations on breaking bad news and performing sensitive exams such as pelvic exams — essential skills often overshadowed by the focus on rare procedures.

Beyond clinical skills, we expanded our didactic series to include sessions on health equity, imposter syndrome, second victim syndrome, and the impact of soft skills on both patient and provider satisfaction. By reinforcing these fundamentals and fostering self-awareness early, we’re building residents who are not only technically strong but also empathetic, confident, and resilient.

You’ve been deeply involved with SAEM since 2014 and have served in every ADIEM leadership role. What has been the most transformative initiative you’ve championed, and why does it still resonate with you today?

One of the most transformative initiatives I’ve had the privilege to help develop was ADIEM’s first pathway program — the Leadership, Engagement, and Academic Pathway (LEAP) Program. Our goal was to create a structured mentorship experience that introduces medical students, starting as early as their third year, to academic emergency medicine and provides them with the tools to become successful faculty members early in their careers.

The program is designed to guide students through each stage of their professional journey — from preparing for the Match, to thriving in residency, to ultimately transitioning into their first faculty role. We welcomed our first two students into the program last year, and it’s been incredibly rewarding to watch them grow — presenting at the SAEM Annual Meeting, engaging confidently on calls, and now beginning their residency interview

continued from Page 7

Dr. Bradby visiting a Richmond tea parlor with her family.

“I try to honor that early mentorship by supporting and encouraging junior learners, remembering how meaningful it can be to have someone believe in you.”

process. Seeing their progress reminds me why intentional mentorship and early exposure to academic medicine matter so much.

As a new member-at-large on the SAEM Board, what are your top priorities moving forward, and how do you hope to influence the organization’s direction in the coming years?

As a new member-at-large on the SAEM Board, my top priority is to deepen my understanding of the organization — how each component, from the SAEM Foundation to our bylaws and governance, works together to advance our mission. It’s been fascinating to see the incredible amount of collaboration and thought that goes into shaping the direction of the organization.

Looking ahead, I hope to help SAEM continue to grow and evolve with the times. Our political, social, and technological landscapes are changing rapidly, and we need to ensure our members — especially our learners and educators — are prepared to adapt and thrive in this new environment.

One area I’m particularly interested in is the responsible integration of artificial intelligence in medicine and medical education. We’re entering a new era of innovation, and as educators, we’re already seeing AI influence applications, evaluations, and letters of recommendation. My goal is to help SAEM lead this conversation thoughtfully — promoting the use of AI as a tool for advancement while remaining vigilant about issues of bias, accuracy, and ethical implementation.

Mentorship is central to academic medicine. How do you mentor residents and students, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds, and what advice do you have for early-career faculty who want to be effective mentors?

Mentorship can easily shift to being about the mentor rather than the mentee, but it should never be that way. The goal is to help your mentee become who they want to be — not a replica of you. I focus on asking thoughtful questions about their goals, values, and what success looks like for them, and then I try to meet them where they are.

For residents and students, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds, intentional mentorship and visibility are critical. I make it a point to create opportunities for them to shine — sending along invitations

to speak, write, or serve on panels that can help build their curriculum vitae and confidence. For junior faculty, this often evolves into true sponsorship — using your platform and connections to help open doors.

For learners, the focus is more on guidance and navigation — helping them understand what’s realistic and what’s possible. That might mean talking through how many residency programs to apply to, how to tailor their application, or how to choose the right environment for their growth. I also remind mentors that today’s trainees are navigating a very different landscape than we did, so our advice has to evolve with the times.

My best advice for new mentors is to set clear goals and expectations at the start of the relationship. Define what both of you hope to gain from the experience. That shared understanding helps frame every conversation and ensures that your guidance stays focused on helping the mentee move confidently toward their own vision of success.

Emergency medicine can be intense and emotionally demanding. How do you recharge and protect against vicarious trauma or burnout, and what do you encourage your trainees to do?

I try not to carry the weight of the emergency department home with me — what happens there, I do my best to leave there. That kind of compartmentalization helps keep the emotional load manageable. Shifting between my clinical and administrative roles also helps prevent burnout; the variety keeps me engaged and focused on new challenges.

I truly love emergency medicine and can’t imagine doing anything else, but my academic roles help sustain that passion and keep me connected to my “why.” Outside of work, I love to travel and spend time at the beach. When I really need to recharge, I escape to the Outer Banks during the off-season — it’s quiet, peaceful, and the perfect place to let my mind settle and just enjoy the rhythm of the waves.

I encourage my trainees to do the same — to always remember why they chose this specialty and this profession in the first place. Take time for yourself, step away when you need to, and find your peace. It’s the only way to sustain the joy and purpose that brought you here.

Dr. Bradby hand knit a blanket at a local art class!

How do you envision the role of emergency medicine evolving in terms of community health, equity, or national health crises—and what role might SAEM and ADIEM play in that vision?

With the constantly shifting political and healthcare landscape, I believe emergency medicine will become more vital than ever as the nation’s healthcare safety net. Our role continues to expand — we’re boarding patients longer, managing increasingly complex care, and often providing what amounts to primary care for those who have nowhere else to turn. The emergency department remains the only place where patients can receive care 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year — regardless of their ability to pay.

As private practices close and rural hospitals disappear, more communities are relying on the emergency department as their only point of access to the healthcare system. This places emergency physicians at the intersection of clinical care, public health, and social justice. We are not only treating medical emergencies but also confronting the consequences of health inequities, limited access, and policy failures.

Organizations like SAEM play a critical role in this evolving space. They help prepare and empower academic and clinical leaders to advocate for equity, strengthen community partnerships, and ensure that our specialty continues to adapt to the changing needs of our patients. Through mentorship, research, and education, SAEM and ADIEM can help guide emergency medicine toward a future that is more inclusive, more responsive, and more resilient.

Up Close and Personal

What’s one thing you always keep in the pocket of your scrubs—and one thing you probably should take out?

As a resident, I probably had more pockets than should be legally allowed — my cargo pants had pockets within pockets. I carried everything from intravenous start kits to bags of gloves to lidocaine and guaiac developer. As an attending, I’ve pared it down to just a pen and a piece of paper.

That said, I probably should remember to take the pen out before tossing my scrubs in the wash — I’ve lost more than a few pieces of clothing to ink splotches this year.

If you had a soundtrack playing behind you during a busy ED shift, what song would be on repeat?

“All I Do Is Win” by DJ Khaled featuring Ludacris, Rick Ross, T-Pain, and Snoop Dogg. It’s upbeat, full of energy, and features an all-star lineup — just like my team in the emergency department. Plus, it always puts me in a positive, winning mindset, which is exactly what you need on a busy shift.

What’s your secret superpower outside of medicine?

I’m a self-proclaimed “find-out-ologist.” If something piques my curiosity, I will find the answer — no matter how deep the internet rabbit hole goes. From the latest celebrity gossip to cutting-edge medical innovations, I’ll track it down, learn it, and probably share it with a few people along the way.

If you’re ever in need of some completely unnecessary but highly entertaining information, I’m your girl.

Who was your childhood hero—and how close is that to what you do now?

My mom. She has always been my superhero. An immigrant from Malaysia, she joined the U.S. military just months after arriving in the country and later served in the National Health Service Corps as a nurse. Her dedication to service and caring for others inspired me to pursue a career in medicine. While nursing wasn’t quite the right fit for me, I found my perfect place in medicine itself.

What’s your favorite way to unwind after a high-stress day?

You can usually find me with some yarn in hand — either working on a new project or hunting for the next pattern to try. Nothing helps me unwind quite like crocheting or knitting (though I’ll admit, I’m much faster with a crochet hook).

Over the years, I’ve made blankets, hats, scarves, and wraps — though sweaters are still on my “someday” list. My mom taught me to crochet when I was a kid, and I’ve been hooked ever since. One of my favorite personal traditions is making a baby blanket for every new baby born in our residency program. What advice do you give to mentees that you secretly still need to remind yourself of, too?

Time doesn’t stop — it’s always moving forward. I often remind my mentees (and myself) to pause and truly enjoy the wins, celebrate with family, and take in the peace and beauty around us.

There’s never a perfect time to start something new — just do it, and the rest will work itself out. Each day is unique, and once it’s gone, you don’t get it back.

ACADEMIC CAREER DEVELOPMENT

Building a Career in Academic Emergency Medicine: A Roadmap for Every Stage

By Bret Nicks, MD, MHA; Justin Myers, DO, MPH; Tim Palmieri, MD; Douglas M. Char, MD, MA; Jennifer Kanapicki Comer, MD; and Christine Ju, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Faculty Development Committee

Emergency medicine is where curiosity meets crisis and where teaching and research are anchored in real-time impact. For those pursuing a career in academic EM, the routes are varied. Success comes from building skills, scholarship, leadership, and service. This roadmap offers practical guidance for building a meaningful career and highlights SAEM resources to support you along the way.

Start Early: Academic Engagement During Residency Residency is the time to develop academic habits that last. Find mentors who match your interests and commit to one or two longitudinal scholarly projects. Say yes to roles that build durable

skills. Teaching small groups, designing simulation cases, writing clinical questions, leading a quality improvement project, or supporting a resident-as-teacher curriculum all help build a teaching portfolio.

SAEM offers structured, high-yield resources for residents that can help you choose scholarly lanes and find collaborators beyond your program. Fellowship curiosity often begins in residency—use SAEM’s searchable directories to explore programs and compare expectations.

Early Career (Years 0–5): Choose a Lane, Build Reputable Work Your first faculty years are the time to identify your niche and engage meaningfully. Turn opportunities into visible, peer-recognized

contributions. Many offers will come your way, but balance departmental needs with your expertise. Take time to reflect—waiting even 24 hours before accepting a new role helps ensure it aligns with your priorities.

SAEM’s Academic Promotion Toolkit provides next steps. Aim for three early-career mileposts:

1. A coherent academic identity (“I study decision tools in PE,” “I build ultrasound education for rural ED physicians”).

2. Tangible artifacts such as curricula, protocols, datasets, manuscripts, or FOAMed outputs.

3. Regional or national presence through speaking, committees, or multicenter collaborations.

“Residency is the time to develop academic habits that last, and finding mentors who match your interests is the most important first step.”

SAEM’s toolkits, guidebooks, and online academic resource (SOAR) library offer step-by-step guidance and topic-specific curricula to smooth the transition from residency to faculty.

Midcareer (Years 6–19): Deepen Expertise, Lead Programs, Advance Rank Midcareer is about scale and stewardship. Translate your niche into leadership—direct ultrasound, didactics, a research program, EMS medical direction, or a global health partnership. Build teams, mentor

junior colleagues, and shift from individual projects to programs with measurable outcomes such as publications, grants, or operational benchmarks.

This is also the time to formalize your promotion dossier, aligning outputs with your track (clinical educator, clinical scholar, research-intensive). Service opportunities broaden your impact and network—journal editorial roles, academy leadership, or committee chairs all expand visibility while advancing the field. The SAEM

Career Roadmap for faculty highlights leadership pathways and points to networks that can foster multicenter work and national reputation.

Late Career (Years 20+): Legacy, Sponsorship, and Field-Shaping Work

Late-career academic physicians shape strategy for departments, health systems, and the specialty. Many serve as vice chairs or chairs, senior editors, or leaders in SAEM

continued on Page 15

“Midcareer is about mentoring junior projects to

continued from Page 13

academies and foundations. The emphasis tilts toward sponsorship while continuing to publish synthesis work, write position statements, secure large grants, or direct crossinstitutional initiatives. This is the time to steward culture, standards, and equity, ensuring excellent emergency care for all.

2. Rebuild mentorship deliberately Identify new mentors and sponsors; join SAEM academies and interest groups to find collaborators.

3. Use structured development. Attend skills courses, seek external consultations, and benchmark with peers. SAEM’s faculty development consultation services can help design growth plans and assess success.

academic promotion toolkit to shape your dossier and align with institutional criteria.

Emergency medicine is more than a specialty; it is a platform for teaching, discovery, leadership, and service. With a clear roadmap and the right SAEM resources, you can craft a career that is meaningful and field-shaping. EM remains the best specialty in the house of medicine, and your academic journey in it is worth every mile. ACADEMIC CAREER

Fellowships: When and Why Fellowships are not required for success but can compress learning curves and expand networks. Consider one if:

• You want a career in academic medicine and need protected time to master methodology (research), pedagogy (education scholarship, simulation), or technical skills (ultrasound, EMS, wilderness).

• You aim for credentials that support division or national leadership roles.

• You need structured mentorship to position for grants or multiinstitutional projects.

SAEM’s fellowship directories help compare curricula, expectations, and alumni outcomes.

Navigating Transitions: When Interests Change (They Will)

Academic careers evolve. You might pivot from operations to education, from global EM to research, or from bench science to policy. Healthy transitions follow three principles:

1. Reframe your narrative, don’t erase it. Connect prior wins to your new lane (“Operational QI experience informs my education scholarship on implementation science”).

Continuous Professional Development: Keep Your Edge

Academic EM rewards lifelong learning. Protect time each quarter to keep your scholarly engine running:

• Skill up: Use SAEM’s SOAR library and career development content to stay current on teaching, research design, equity, and leadership.

• Network with purpose: Present annually, volunteer for abstract review, or join a multicenter consortium.

• Document impact: Maintain a living CV and teaching/service portfolio. Align your outputs with promotion criteria. SAEM’s guides and AEM Education & Training literature can help you translate work into promotable artifacts.

Your Next Step (Wherever You Are)

• Resident: Find two mentors, start one project you can finish, and present nationally. Explore SAEM’s approved fellowships if you want structured mentorship and depth.

• Early faculty: Define your niche in one sentence. Produce visible work such as presentations, publications, or curricula.

• Mid/late career: Scale programs and sponsor others. Use SAEM’s

about scale and stewardship—building teams, junior colleagues, and shifting from individual to programs with measurable outcomes.”

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Nicks is a professor and executive vice chair of emergency medicine at Wake Forest University School of Medicine and Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center.

Dr. Myers is an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. He is director of faculty education and the global emergency medicine fellowship.

Dr. Palmieri is an associate professor of emergency medicine at Albany Medical College, associate program director for the residency program, and associate course director for the college’s course in evidence-based healthcare.

Dr. Char is a professor and vice chair of academic and faculty affairs at Washington University School of Medicine.

Dr. Kanapicki Comer is an associate professor of emergency medicine at Stanford University and co-director of the medical education scholarship fellowship and director of faculty development.

Dr. Ju is an assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine at UTHealth Houston McGovern Medical School. She is director of undergraduate medical education, emergency medicine specialty advisor, and co-director of the acute care career focus track.

ASK THE PHARMACIST

High-Dose Insulin Therapy: A Life-Saving Strategy for Cardiovascular Drug Overdose

By Reem Alsultan, PharmD; Dawn R. Sollee, PharmD; Reeves Simmons, PharmD; and Charles Foster, PharmD, on behalf of the SAEM Academy of Emergency Medicine Pharmacists

Cardiovascular drugs are among the most frequently reported ingestions to poison centers, ranking fifth overall behind analgesics, antidepressants, antihistamines and alcohols in 2023. Calcium channel blockers and beta blockers are ranked sixth and seventh, respectively, for being associated with the largest number of fatalities, behind acetaminophen, sedatives/ hypnotics/antipsychotics, alcohols, opioids and stimulants/street drugs.

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic therapy (HIET), also known as high-dose insulin euglycemia, is a valuable treatment option in the management of calcium channel

blocker and beta blocker toxicity. Several mechanisms of action have been proposed to describe the therapeutic benefits of HIET in this setting.

Proposed Mechanisms of HIET in CCB/BB Toxicity

• Provides glucose to the heart for energy utilization

• Increases cardiac output by enhancing nitric oxide synthase

• Impairs Na+/Ca2+ exchange to retain intracellular calcium

• Improves endocrine dysfunction (hyperglycemia) found in severe calcium channel blocker overdose

Place of HIET in Therapy

Toxicity from calcium channel blocker and beta blocker ingestion classically presents with hypotension and bradycardia. Initial treatment includes intravenous (IV) fluids to support blood pressure, in addition to adjunctive therapies such as atropine and calcium (for calcium channel blocker toxicity) or glucagon (for beta blocker toxicity) to address bradycardia. If hypotension is refractory to IV fluids, the next step is to start a vasopressor such as norepinephrine, with a key decision point being whether to also initiate treatment with HIET. Insulin, especially at high

doses, produces potent inotropic and vasodilatory effects, improving cardiac contractility, increasing myocardial glucose uptake, and enhancing perfusion to the heart.

Special Considerations With Calcium Channel Blocker Toxicity

Non-dihydropyridine (non-DHP) calcium channel blockers such as verapamil and diltiazem exert their primary effects on the myocardium. In the setting of overdose, this can result in marked myocardial depression, making HIET particularly effective because of its inotropic effect.

In contrast, dihydropyridine (DHP) calcium channel blockers such as amlodipine act mainly on vascular smooth muscle with minimal effects on the myocardium at usual dosages. In overdose, however, most notably with amlodipine, synthesis of nitric oxide is increased in a dosedependent manner, which produces profound vasoplegia rather than the myocardial depression commonly associated with non-DHPs. Because HIET can also produce peripheral vasodilatory effects, it does not address this vasoplegic physiology and may even exacerbate distributive shock.

For this reason, HIET may not be prioritized as highly in the management algorithm for DHP calcium channel blocker toxicity compared with treatment of nonDHP toxicity. When a DHP calcium channel blocker is the predominant ingestant, vasopressors play the main role in addressing vasoplegia, with HIET often reserved for cases where

Subclass Examples

Dihydropyridines

Nondihydropyridines

myocardial depression is evident. It should be mentioned, however, that pharmacological selectivity between DHP and non-DHP calcium channel blockers can become blurred in the midst of excessively high levels in systemic circulation, such as in overdose.

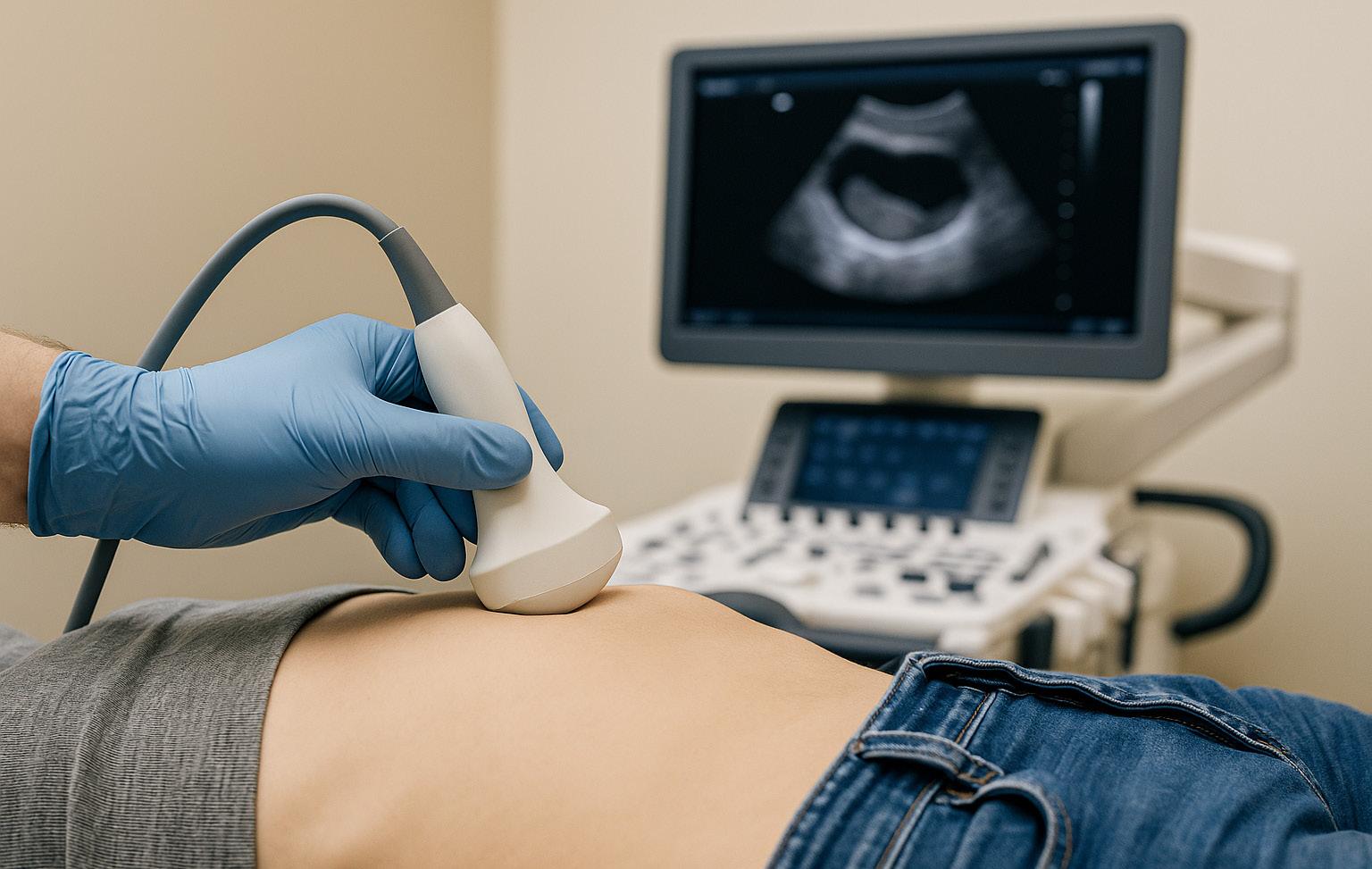

Patient’s Clinical Status

Clinical status ultimately guides therapy decisions regardless of the ingested agent (beta blocker, DHP calcium channel blocker or non-DHP calcium channel blocker), and HIET is likely appropriate for initiation when there is evidence of reduced cardiac contractility. If a bedside echocardiogram or ultrasound reveals a reduced ejection fraction, initiating HIET for inotropic support may be beneficial, even with DHP calcium channel blocker toxicity, to improve contractility and perfusion. Other therapies that have been tried in cases of refractory vasoplegia include nitric oxide scavengers such as methylene blue and hydroxocobalamin.

HIET Dosing and Titration

Reported dosing strategies for HIET vary in the literature, but the usual dose is approximately 10 times higher than what is needed for managing diabetic ketoacidosis. This can understandably lead to practitioner hesitation when considering HIET; however, with frequent lab monitoring and judicious supplementation of glucose and electrolytes, this resource-intensive therapy can be implemented safely as a potentially life-saving treatment for cardiac drug poisonings.

Primary Sites of Action Main Therapeutic Effects

Before starting the insulin infusion, obtain baseline blood glucose and serum potassium. If blood glucose is less than 200 milligrams per deciliter, administer 25 to 50 grams of IV dextrose. A continuous IV infusion of 10 percent dextrose (peripheral line) or 20 percent dextrose (central line) should also be initiated and titrated during HIET to maintain glucose between 100 and 200 milligrams per deciliter. If potassium is less than 3 milliequivalents per liter at baseline, provide supplementation before starting HIET.

When ready to begin, administer an IV bolus of 1 unit per kilogram of regular insulin using actual body weight (no consensus on a maximum weight), followed by a continuous IV infusion of 1 unit per kilogram per hour.

HIET should be titrated every 15 to 30 minutes as needed, based on cardiac output parameters (contractility and perfusion) and blood pressure:

• Contractility: Assess by bedside ultrasound in the emergency department. Increase HIET rate if ejection fraction is less than 50 percent.

• Perfusion: Target urine output greater than 0.5 milliliters per kilogram per hour, warm skin with normal color, palpable peripheral pulses and improving serum markers (basic metabolic panel, lactate, venous blood gas).

• Blood pressure: Goal is systolic blood pressure 90 millimeters of mercury or higher, or mean arterial pressure 60 millimeters of mercury or higher.

Amlodipine, Nifedipine, Nicardipine, Clevidipine

Verapamil

Diltiazem

Vascular smooth muscle

Myocardium & AV node

Intermediate (AV node + some vascular)

Potent arterial vasodilation

↓SVR, ↓BP (minimal cardiac conduction effect)

↓HR (negative chronotropy), ↓contractility (negative inotropy), ↓AV conduction

Slows AV conduction, modest ↓HR, moderate vasodilation

SVR, systemic vascular resistance; BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; AV, atrioventricular

Clinicians should not rely solely on blood pressure goals to guide therapy. HIET can lower vascular tone, while vasopressors may raise mean arterial pressure without improving tissue perfusion. HIET should instead be titrated based on contractility, perfusion and blood pressure goals, up to 10 units per kilogram per hour

continued on Page 18

CCB or BB overdose with hypotension

refractory to IV fluids, calcium, and atropine

It can be cardiogenic shock:

Start HIET with 1 unit/kg bolus followed by infusion of 1 units/kg/h + D10W infusion.

Titrate up by 1-2 units/kg/hour every 15-30 mins up to a MAX of 10 unit/kg/h based on cardiac output goal parameters

Consider adding: Epinephrine infusion, other inotropes, and pacemaker placement.

ConsiderconsultECMOteam

It can be distributive shock:

Increase norepinephrine infusion

Consider vasopressin

Consider methylene blue or hydroxocobalamin if refractory

ASK THE PHARMACIST

continued from Page 17

Risk of Volume Overload

Administering high amounts of insulin using a standard concentration (1 unit per milliliter) for IV infusion can lead to potential volume overload, especially in patients who may already be in distributive shock. Using concentrated preparations of insulin (for example, 16 units per milliliter) can reduce total fluid volume administered. Institutions should ensure safety measures are in place and provide education to nurses, pharmacists and providers to prevent confusion between concentrated and standard insulin drips.

“Insulin, especially at high vasodilatory effects, improving glucose uptake, and

Atropine

Glucagon

Epinephrine infusion

Inotropes

Pacemaker placement (if refractory bradycardia)

minimize volume and decrease the risk of hypoglycemia. Blood glucose should be monitored every 20 to 30 minutes for the first four hours following insulin initiation. If blood glucose is 100 to 200 milligrams per deciliter at hour four and the insulin drip rate is stable (no further titration needed to maintain hemodynamic stability and perfusion), monitoring may be reduced to every hour while HIET is running.

Blood sugar checks should continue for at least four hours after HIET is stopped to monitor for hypoglycemia, as it may take time for accumulated insulin to clear. When serum glucose levels begin to stabilize, it may indicate resolution of calcium channel blocker overdose. This observation does not apply to beta blocker overdoses.

HIET Monitoring

Frequent lab draws and attentive patient monitoring are imperative. While insulin greatly improves glucose uptake by myocardial cells, hypoglycemic events and significant electrolyte derangements can occur fairly quickly due to the amount of insulin being administered. Some have reported a hypoglycemia incidence of 31 percent—a common risk during HIET, albeit one that can be avoided with appropriate monitoring and supplementation of glucose.

The optimal glucose level during HIET is not defined but is typically targeted at 100 to 200 milligrams per deciliter using dextrose infusions. In patients with central venous access, concentrated dextrose solutions (20 percent or greater) are preferred to

For potassium, the target concentration during HIET is not well defined, but maintaining a mild hypokalemic range (2.7-3.2 milliequivalents per liter) is common, with monitoring every one to two hours during initial stabilization and with any titration of insulin. Aggressive potassium repletion is not recommended, and a lower potassium goal is appropriate to avoid rebound hyperkalemia once the insulin infusion is stopped and extracellular potassium shifts occur.

HIET Duration and Discontinuation

Duration of HIET varies based on clinical response. In the available literature, infusion durations range from a single insulin bolus to infusions lasting hours to days. On average, insulin duration is reported as 24 to 31 hours.

When considering discontinuation, vasopressors and other inotropes

should be tapered off before HIET is discontinued, as HIET is vasopressorsparing and abrupt discontinuation may precipitate cardiogenic shock. There is no consensus on how to discontinue HIET. One method is to decrease the rate by half every one to four hours; another is to decrease the infusion by 1 unit per kilogram per hour. Insulin levels can remain elevated even after discontinuation, so blood glucose, symptoms of hypoglycemia and potassium concentrations should be monitored for at least 24 hours afterward.

Standardizing for Safety and Effectiveness

Using HIET as a potential life-saving treatment in cases of beta blocker and calcium channel blocker overdose should be available in all emergency departments. Standardized protocols outlining dosing, monitoring and titration parameters are essential for safe and effective use. When designing a protocol, a multidisciplinary approach is best, and clinicians are encouraged to consult their local poison center at 1-800-222-1222

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Alsultan is a clinical pharmacy specialist in emergency medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

Dr. Sollee is a professor at the University of Florida College of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, a clinical toxicologist, and the director of the Florida/USVI Poison Information Center –Jacksonville.

Dr. Simmons is the assistant director of the Florida/USVI Poison Information Center – Jacksonville, a clinical toxicologist, and an emergency medicine pharmacist at UF Health Jacksonville.

Dr. Foster is a clinical content specialist with Merative, Micromedex, and an emergency medicine pharmacist at Poudre Valley Hospital in Fort Collins, Colorado, and the Medical Center of the Rockies in Loveland, Colorado.

Improving Patient and Staff Safety in the ED Through Standardized Behavioral Health Intake

By Mary-Kate Gorlick, MD; Catherine Reynolds, MD; and Kunal Sharma, MD, MBA

Background

Behavioral health patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) require timely and coordinated care, yet triage, intake and assessment processes are often fragmented and inconsistent. At Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital in Houston (LBJ Hospital), behavioral health triage and intake historically occurred in the main ED triage area, a crowded and overstimulating environment not designed for patients in psychiatric crisis. There was no standardized nursing involvement, variable provider participation and inconsistent safety protocols, all of which contributed to delays

in evaluation, safety events such as elopement and ingestion, and inefficiencies in documentation. These challenges were not only frustrating but unsafe and often left staff feeling that they had little control over their own well-being at work.

Intervention

In May 2025, we implemented a new standardized behavioral health intake (BHI) process designed to improve safety, efficiency and coordination of care. Intake was relocated from ED triage to a quieter, dedicated pod, better suited for psychiatric evaluation. A multidisciplinary team

was established, integrating intake nurses, technicians, providers and security into a unified process. All participants in the intake process were assigned defined roles to reduce duplication of effort and improve accountability. Security presence was streamlined to ensure continual coverage, supported by weapons detectors and managed belongings to reduce risk of violence.

A structured risk stratification system was introduced. Patients were classified as low, medium or high risk in consensus with the intake team. Low-risk patients returned to the general ED for

“Median arrival-to-provider times decreased by nearly 50 percent, arrival-to-psychiatry consult times decreased by more than 60 percent, and overall emergency department length of stay for this patient group decreased by one-third.”

standard evaluation and disposition. Medium- and high-risk patients received expedited psychiatric consultation when appropriate, safety sitters and psychotropic medications if clinically indicated. This approach allowed for consistency and timeliness in patient care and important safety interventions for higher-risk patients. It also minimized unnecessary delays for those who did not require extended psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Standardized documentation tools were developed and embedded in the electronic health record. Smart phrases, checklists and a risk assessment tool helped ensure that critical safety information was captured reliably and consistently.

Results

The new BHI process produced measurable and meaningful improvements. Median arrival-toprovider times decreased by nearly 50 percent, arrival-to-psychiatry consult times decreased by more than 60 percent, and overall ED length of stay for this patient group decreased by one-third. Importantly, there have been no patient elopements since the standardized intake process was launched. Safety risks such as ingestion were more reliably identified, with appropriate precautions implemented earlier in the patient’s ED course. The process also had added benefits in identification and safe disposition of other patients who lacked decision-making capacity, including those with undifferentiated encephalopathy and unaccompanied minors.

Staff reported greater efficiency, clarity of responsibilities and a stronger sense of both psychological and physical safety. Many noted that the dedicated space and team-based model reduced stress, improved communication and allowed them to focus more fully on patient care rather than environmental and workflow challenges.

Challenges and Next Steps

While the new workflow addressed many critical gaps, challenges remain. The administration of nonemergent psychotropic medications in the ED requires formal patient consent under state regulation, which can delay initiation of treatment. Work is ongoing to refine the consent process and ensure that patients receive timely access to appropriate medications. Further, the new BHI process required the dedication of nine ED care spaces to support the intake process and subsequent bedding of each patient, which has the potential to worsen crowding and boarding in other care areas. Additional efforts are focused on sustaining standardized practices, optimizing the patient flow for medium-risk cases and expanding staff education to reinforce safety and efficiency.

Conclusions

The implementation of a standardized BHI process in the LBJ ED has improved timeliness of evaluation, reduced length of stay, enhanced patient and staff safety and strengthened staff experience. By relocating intake to a dedicated pod, coordinating clinical and security teams and applying structured risk

stratification, the ED has created a more reliable and patient-centered process for behavioral health care.

This initiative underscores three major wins: standardization brought clarity to roles, responsibilities and actions; operational metrics such as length of stay and elopements improved; and patient and staff safety—including staff psychological safety—was strengthened. Relatively straightforward operational changes can have a profound impact not only on patient outcomes but also on staff well-being, retention and performance. We believe this model can be adapted by other institutions and hope to spark dialogue and collaboration as we continue refining the process and preparing for formal publication.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Gorlick is an assistant medical director of emergency medicine at Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital in the department of emergency medicine at UTHealth Houston.

Dr. Sharma is a vice chief of staff for quality at Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital and a vice chair of clinical affairs in the department of emergency medicine at UTHealth Houston.

Dr. Reynolds is a chief of service of emergency medicine at Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital in the department of emergency medicine at UTHealth Houston.

CAREER PATHWAYS

From Bench to Bedside: Careers in Emergency Medicine Innovation and Translational Research

By Sara Schulwolf, MD, on behalf of SAEM Residents and Medical Students (RAMS)

Innovation and translational research are reshaping the future of emergency medicine, bringing new ways to move discoveries from the laboratory to the bedside. To explore how these advances are opening career opportunities for trainees, Sara Schulwolf, MD, spoke with two leaders in the field. Dr. Christopher Kabrhel and Dr. Drew Birrenkott share their paths into research, insights on innovation, and advice for residents and medical students interested in charting their own careers in this rapidly evolving area of emergency medicine.

Christopher Kabrhel, MD, MPH, is an emergency physician and director of the Center for Vascular Emergencies at Massachusetts

General Hospital. His research focuses on the epidemiology, diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment of venous thromboembolism. He leads a multidisciplinary team developing innovative approaches to diagnosis, risk stratification, and care delivery.

Dr. Drew Birrenkott

Drew Birrenkott, MD, DPhil, is an emergency physician and the inaugural fellow in clinical innovation and research translation in vascular emergencies at Mass General Brigham. He earned his doctorate in biomedical engineering with a focus on signal processing and machine learning and now uses proteomics to identify novel biomarkers for pulmonary embolism diagnosis.

Drs. Kabrhel and Birrenkott, please provide a brief primer on translational research and the integration of omics, big data, and artificial intelligence. How will this shape the future of emergency medicine practice?

Translational research moves scientific innovations from “bench to bedside.” The goal is to use basic

“Now my research omics and artificial of venous thromboembolism tests and treatments.”

research to design tests, devices, and drugs that improve clinical care. To be successful, researchers must consider the validity of the science, the clinical usefulness and usability of the test or treatment, and how it can be implemented into existing workflows, regulatory frameworks, and economic systems.

Innovations in omics, big data, and AI offer many opportunities for emergency physicians to participate in translational research. Historically, translational research meant moving a molecule or technology from the lab to the hospital. Now, we can

create predictive models using large data sets with complex omics and patient-level descriptors. This builds on decades of emergency medicine research in clinical decision rules. The growth of these fields will accelerate the process, and when models are implemented into workflows, they will improve patient outcomes.

Dr. Kabrhel, you’re best known for your work on VTE and creating decision tools to guide risk stratification of patients with potential PE. How did you become interested in this area?

During my ICU rotation in medical school, I learned why PE causes

research is coming full circle, as we use modern intelligence to explore the molecular basis thromboembolism and develop new diagnostic treatments.” — Dr. Christopher Kabrhel

hypoxia—which intuitively it shouldn’t, since it’s primarily a dead-space phenomenon. This sparked my interest in the molecular basis of PE, so as a resident I proposed a project to Dr. Sam Goldhaber, a renowned PE expert. My idea was comically ambitious, but Sam agreed to mentor me anyway—on a more realistic project.

We prospectively enrolled patients in the ED to validate the Wells score, which was new at the time. Shortly after, I was introduced to Jeff Kline, who had the idea for what would become the PERC rule. We combined our data, and my research career took off. Since then, I’ve worked on VTE epidemiology, diagnosis, risk stratification, and programs like PERT. Now my research is coming full circle, as we use modern omics and AI to explore the molecular basis of VTE and develop new diagnostic tests and treatments.

Dr. Birrenkott, how did you become interested in pursuing this career path? I became interested in translational

continued on Page 25

“My advice is that it is never too early to get involved. Everyone’s path is different, but as a student or resident you have the chance to try different opportunities.” — Dr. Drew Birrenkott

CAREER PATHWAYS

continued from Page 23

research during my biomedical engineering courses as an undergraduate. Many design classes assigned real-world problems and required a deliverable product or prototype by the end of the course. That meant collecting and analyzing data to compare the product to existing technology. I now think about how we can apply this model to challenges in emergency medicine.

As a specialty, we are still relatively young, but we have the unique ability to collect large amounts of high-quality clinical data at the time undifferentiated patients present with acute illness. Leveraging this data, along with the electronic health record, omics, and AI, I believe emergency physicians can become leaders in developing new acute diagnostics.

Dr. Birrenkott, as a student and resident, what steps did you take to pursue this field? What advice do you have for trainees?

To set myself up for success, I did three things. First, I sought opportunities to get involved at my institutions and within the emergency medicine community. I highly recommend engaging with SAEM. For example, as a resident, I participated in the 2024 omics consensus

conference, which allowed me to meet clinicians working in translational research.

Second, I sought out mentorship during medical school and residency. That network has been invaluable. Finally, I always looked ahead. Once I knew this was the work I wanted to do, I began talking with mentors about what my next steps should be after residency.

My advice is that it’s never too early to get involved. Everyone’s path is different, but as a student or resident you have the chance to try different opportunities. Talk to people doing innovative work at your institution and beyond. Find mentors and get involved. One of the reasons we wrote this article is to reach medical students and residents. If you’re not sure where to start, this is your invitation to reach out to us.

Dr. Birrenkott, you recently began a fellowship in clinical innovation and research translation. What does this fellowship offer trainees, and what expertise will graduates gain?

As the inaugural fellow, I can say this program offers opportunities beyond a traditional research fellowship. Typical research fellowships provide projects, grant writing education, a didactic curriculum, and often a degree program. Our fellowship includes those but adds skills for translating research into practice.

That includes collaborations with engineers, computer scientists, and computational biologists, plus access to innovation officers, intellectual property experts, industry partners, investors, and clinicians who have successfully translated their work.

The fellowship gives a survey of the innovation landscape and connects trainees with people who can guide the process of moving research from bench to bedside.

Drs. Kabrhel and Birrenkott, tell us about your current projects. What are you most excited about?

We’re especially excited about two projects. The first is the Automated Registry of Cardiovascular Emergencies (ARCVE), a collaborative registry with colleagues at Vanderbilt and other centers. ARCVE includes data on about 400,000 ED patients evaluated for possible PE, and it’s growing rapidly. We are using this registry to build predictive AI models for PE diagnosis and treatment.

The second area is high-throughput proteomics and metabolomics to improve PE diagnostics. These two data sources integrate well. For example, we can harmonize ARCVE’s clinical data with our proteomic data to enhance analysis.

Drs. Kabrhel and Birrenkott, your work relies heavily on interdisciplinary partnerships. What unique skills do EM physicians bring to the table?

Collaborating with experts from other fields is fun and energizing, but emergency physicians bring unique strengths. We care for patients with acute, undifferentiated illness. We have access to patients and samples, and we know firsthand how they present and what’s needed for rapid, accurate diagnosis. That’s why emergency physicians need to be at the forefront of this science.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Dr. Schulwolf is a resident physician at the Harvard Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency at Mass General Brigham and a member-at-large on the SAEM RAMS Board.

CAREER PATHWAYS

From Residency to Leadership in Academic Emergency Medicine

By Mel Ebeling, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Membership Committee

The path to academic emergency medicine is rarely straightforward. For many physicians-in-training, it is shaped by moments of inspiration, strong mentorship, and opportunities to step into leadership roles. To explore how today’s residents are charting their careers — and how they are already shaping the field — Dr. Mel Ebeling spoke with three members of the SAEM Residents and Medical Students (RAMS) Board.

Lauren Diercks, MD, is a resident physician at Stanford University and secretarytreasurer on the SAEM-RAMS Board.

Juliet Jacobson, MD, is a resident physician at NewYorkPresbyterian/ Weill Cornell and Columbia University and a member-atlarge on the SAEM-RAMS Board.

Indrani Guzmán Das, MD, MPH, is a resident physician at Stanford University and a member-atlarge on the SAEMRAMS Board.

In the following conversation, they share their journeys into

emergency medicine, the mentors who shaped them, the challenges and opportunities of serving on the RAMS Board, and their advice for students and residents eager to grow in academic EM. Their stories highlight the importance of career development — building skills, seeking mentorship, and finding ways to contribute meaningfully to the profession while still in training. Why did you choose emergency medicine?

Dr. Diercks: “I grew up with my family serving on ski patrol. A pivotal moment came when a cardiac arrest happened on the slopes. My aunt, an accountant, performed CPR while I

Dr. Lauren Diercks

Dr. Juliet Jacobson

Dr. Indrani Guzmán Das

“Meeting people who do EM in different settings gave me perspective and made me more receptive to diverse viewpoints—all in the best interest of the patient.”

— Dr. Juliet Jacobson

kept the patient’s daughter away. He survived after being transported in a toboggan, receiving CPR and bagging en route, and being flown out. That inspired experience shaped my desire become a physician. Now, in full circle, I’m about to be a certified ski patroller at the same place my family served.”

Dr. Guzmán Das: “I chose emergency medicine because during medical school it was the one rotation where people were genuinely excited to teach and eager to involve me. My background in health economics and passion for health equity also drew me in, since the emergency department is often the access point for patients when cost or medical debt prevents them from seeing a primary care physician. Finally, I value the camaraderie—the team dynamic among physicians, nurses, techs, and clerks is unique and motivating.”

Dr. Jacobson: “I didn’t have an ‘aha’ moment. As a child, I considered careers from cleaning to being a chef before realizing I loved science. In a pre-med program, while others were terrified of the emergency department, I loved it. Hearing a code made me want to run toward it. In medical school, I struggled to choose a specialty, but emergency medicine combined everything I loved—I didn’t have to choose.”

Who has influenced your path in academic emergency medicine, and how did they shape your goals or leadership journey?

Dr. Diercks: “Although my aunt inspired me initially, my mother is an emergency medicine physician and

both an academic leader and strong clinician. My younger sister, who is applying to emergency medicine this year, also pushed me forward. She’s followed my path—from our sorority and major to medical school, and now EM. Knowing she looks to me pushes me to a thoughtful doctor and make good choices.”

Dr. Guzmán Das: “Dr. Giovanni Rodriguez, a former RAMS Board member, encouraged me to attend conferences, apply for opportunities, and not be discouraged by rejections. Her advice—to keep showing up— opened doors I hadn’t expected, and I pursued leadership in part by following her example.”

Dr. Jacobson: “My mentor, Dr. Mike DeFilippo, was on the RAMS Board when I was an intern. He encouraged me to apply for leadership positions. His support gave me the confidence to pursue these roles.”

How did you first get involved in SAEM or RAMS, and what drew you to it?

Dr. Diercks: “In my first year of medical school, I submitted an abstract to the virtual SAEM annual meeting during COVID-19. I later joined the SAEM Medical Student Ambassador program and discovered the RAMS Board. Even earlier, I knew I wanted to be a leader in EM, and SAEM aligned with my academic interests and my desire to be part of the broader EM community.”

Dr. Guzmán Das: “At Cornell, part of the New York Presbyterian network, I was surrounded by EM leaders, so academic EM was on my radar early. With encouragement from

mentors like Dr. Rodriguez, SAEM and RAMS became natural next steps for opportunities and leadership development.”

Dr. Jacobson: “There was no EM residency at my third-year rotation site, so I had to find my own mentors. I wish I had known about SAEM sooner. Once I discovered RAMS in residency, I loved it and wanted to strengthen its resources—especially the website’s accessibility for students.”

What has been the most meaningful RAMS project or initiative you’ve worked on, and what impact has it had on you and others?

Dr. Diercks: “One of our biggest challenges and most meaningful efforts as a Board was identifying our brand. At first, we weren’t sure how to connect with medical students across the country or what message to convey. Over time, we defined RAMS as the premier academic EM organization for students and residents—and our work now centers on delivering resources that reflect that identity.”

Dr. Guzmán Das: “Many of my projects focus on mentorship and career growth. I’ve worked on a podcast featuring advice from department chairs, developed jobsearch resources, and helped launch a mentorship program to connect RAMs with faculty at the SAEM annual meeting. These projects build stronger networks and support systems for our community.”

continued on Page 29

“There’s true camaraderie in the emergency department. Everyone— physicians, nurses, techs, clerks—plays this team sport.” — Dr. Guzmán Das

CAREER PATHWAYS

continued from Page 27

Dr. Jacobson: “Developing an EMIG curriculum and supporting students in tailoring it to their schools demonstrated to me how small contributions can have national impact and reinforced the value of sharing resources across programs.” What challenges have you faced during your time on the RAMS Board, and how have you worked through them while balancing other responsibilities?

Dr. Diercks: “When I first joined the Board, the challenge was clarifying our brand and learning how to communicate with medical students nationwide. Over time, we built a clear identity and developed strategies to connect meaningfully with students and residents.”

Dr. Jacobson: “Becoming chief resident and joining the RAMS Board at the same time was overwhelming, especially with a fellowship added during my fourth year. I learned to say ‘no,’ stay organized, and lean on my support system.”

Looking ahead, what excites you about the future of academic emergency medicine and RAMS, and what role do you see residents playing in shaping that future?

Dr. Diercks: “I hope RAMS strengthens its message to medical students and expands opportunities —publications, projects, or committee roles — that boost their resumes while advancing the specialty.”

Dr. Guzmán Das: “As digital natives, residents are uniquely positioned to harness new technologies in the ED. Artificial intelligence, for example, could help screen patients, simplify discharge instructions, and reduce jargon, freeing time for patient interaction and to address systemic challenges.”

What lessons, passions, or personal interests have helped ground you, and how do they influence the way you show up as a physician?

Dr. Diercks: “My mother and sister

remind me that my actions and decisions ripple beyond myself. Being a role model to my sister grounds me to stay thoughtful.”

Dr. Guzmán Das: “I joined a ceramics studio when I started residency, and it has taught me to accept failure gracefully. Hiking, time outdoors recharge me. Adopting a dog and that unconditional companionship, helps me separate work from personal life. These passions help me bring my best self to patients.”

Dr. Jacobson: “My biggest takeaway from RAMS has been learning from colleagues who are practicing in very different environments. It’s helped me appreciate the resources at my own institution and stay open to diverse perspectives. That mindset has grounded me in both clinical practice and collaboration.”

What advice would you give to residents or students interested in academic emergency medicine or RAMS?

Dr. Diercks: “Build connections with colleagues during your off-service rotations. You’ll be working with many of them later as consultants, and it’s much easier when you already recognize familiar faces across the hospital.”

Dr. Guzmán Das: “My advice is simple: apply and get involved. Even if you don’t see leaders who remind you of yourself, your perspective is valuable and welcome. Don’t underestimate what you bring to the table.”

Dr. Jacobson: “Be open to anything. In EM, you must be comfortable with everything, but you can still carve out your niche. SAEM academies and interest groups are great places to meet people with similar interests and find projects to join.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Ebeling is an emergency medicine resident physician at the University of Cincinnati and RAMS Board Member-At-Large

EDUCATION & TRAINING

Shaping the Future of Emergency Medicine Training: Inside the ACGME’s Proposed Revisions

By Daniel Artiga, MD; Mel Ebeling MD; Carlisle Topping; Lauren Querin, MD, MEd; and Adebisi Adeyeye, MBBS, MSc, on behalf of SAEM Residents and Medical Students (RAMS)

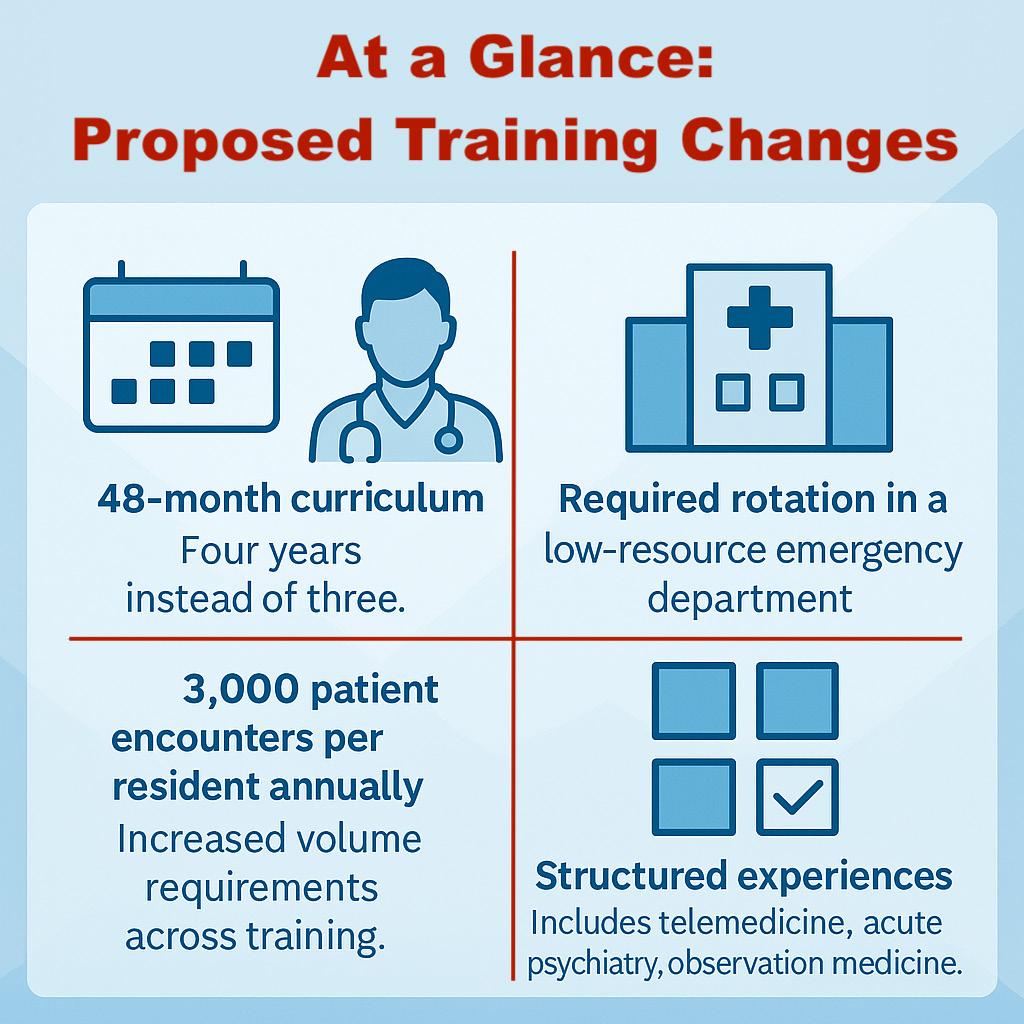

In February 2025, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) proposed major revisions to the emergency medicine (EM) residency program requirements, sparking dialogue and debate within the specialty. The proposed revisions include a new 48-month curriculum, an aggregate annual volume per resident of 3,000 patient encounters, and the addition of a required rotation in a lowresource emergency department,

among other changes. If approved, the revisions would take effect no earlier than July 1, 2027.

To appreciate the significance of the proposal, it is important to understand the ACGME’s process for revising specialty-specific program requirements. This article outlines that process, the key stakeholders, how the proposed revisions were developed, and what to expect in the coming months.

Why Now?

The ACGME reviews specialtyspecific program requirements at the least every 10 years, following a standardized process that engages multiple stakeholders. These periodic reviews aim to advance medical education and prepare physicians to meet evolving patient and system needs.

The proposed EM program requirement revisions are not

“The proposed revisions include a new 48-month curriculum, an aggregate annual volume per resident of 3,000 patient encounters, and the addition of a required rotation in a lowresource emergency department, among other changes.”

intended as a critique of existing programs, a means of influencing workforce distribution, or a strategy to diminish smaller programs or contract management groups. Rather, they are part of the ACGME’s routine review cycle and were shaped by feedback and insights from within the EM community.

Who Makes the Changes?

Four ACGME entities are involved in the development and approval of EM program requirements:

Emergency Medicine Program

Requirements Writing Group (PRWG)

Includes eight EM attending physicians, one EM resident physician, two public members, and nine ACGME staff, including three from the Review Committee (RC). The PRWG led the multi-stage process of drafting the proposed revisions.

Emergency Medicine Review Committee (RC)

Composed of 13 members: 11 nominated by the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), American Medical Association (AMA), and American Osteopathic Association (AOA); one resident member; and one public member. Members include past EM society presidents, national conference leaders, and nearly all are current or former program directors or designated institutional officials. The RC reviews the proposed revisions before they are sent forward. Current members of the RC can be viewed here. Selection criteria can be found here

Committee on Requirements (CoR)

A committee appointed by the ACGME Board of Directors The CoR reviews proposals from the RC and ensures revisions align with the ACGME mission before forwarding recommendations.

ACGME Board of Directors

Composed of 24 members nominated by seven member organizations, along with resident physicians, public directors, at-large directors, and other

appointed representatives. The Board is the final approving body for all program requirements. The current ACGME Board can be viewed here

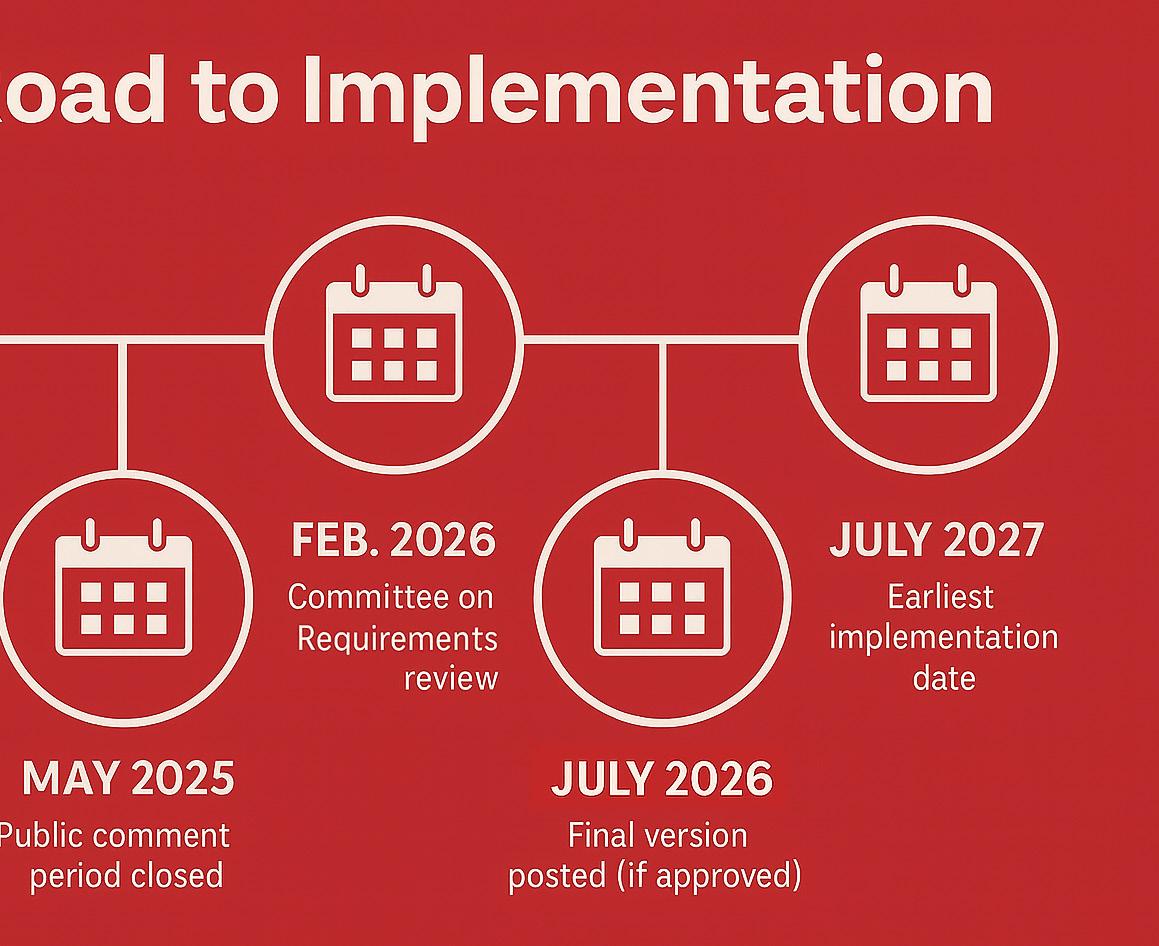

Revision Timeline

Since 2023, the Program

Requirements Writing Group (PRWG) has gathered input through a strategic planning session, stakeholder summit, and program director survey. The

continued on Page 32

continued from Page 31

proposal was posted for public comment in February 2025, with final approval by the ACGME Board expected in February 2026 and implementation no earlier than July 2027.

How the Proposed Revisions Were Developed

The ACGME piloted its forwardlooking revision model in internal medicine (2018) and general surgery (2022) Emergency medicine adopted a similar process, beginning with the PRWG.

Strategic Planning

The PRWG held a four-day strategic planning session with an external facilitator. The group reviewed evidence, procedural competencies, resident workload, and the evolving scope of EM practice. They also conducted interviews with EM leaders, program directors, and recent graduates in both community and academic settings to ensure perspectives were broad.

Stakeholder Summit

A stakeholder summit followed, bringing together representatives from societies including SAEM, Association of Academic Chairs of Emergency Medicine (AACEM), Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors (CORD), ACEP, American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians (ACOEP), American Academy of Emergency Medicine (AAEM), Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA), Residents and Students Association of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine (RSA), ABEM, and the American Osteopathic Board of Emergency Medicine (AOBEM), along with the RC past chair and two recent graduates. Participants were asked: “What training will emergency physicians need to practice effectively in 2050?”

Key Insights

Themes included inefficiencies in patient care (low patient volume

per hour), limited understanding of administration (billing and coding, quality assurance), and declining competency with common loweracuity procedures (e.g., suturing, incision and drainage, fracture reduction). The need for stronger training in pediatrics was identified, along with an expanded focus in addiction medicine, EMS, obstetrics/ gynecology, toxicology, point-of-care ultrasound, telemedicine, observation medicine, and transitions of care.

Taken together, these insights highlighted the need to prepare emergency medicine residents not only as skilled clinicians but also as leaders capable of working within complex, multidisciplinary health systems. This perspective shaped a new vision of the future emergency physician and guided the development of the core competencies and curriculum elements. The result was a de novo curriculum designed not on existing structures, but on consensus around the competencies required for future EM physicians.

Curriculum Highlights

The new curriculum includes traditional rotations, structured experiences, and procedural competency expectations. The PRWG also emphasized the need for diverse clinical exposure across varying acuity levels and resource environments, while accounting for the number of patient encounters in the ED and the ICU

“Structured experiences” are distinct educational activities that may not require a minimum block rotation but provide essential exposure. Nine were identified, including acute psychiatry, airway management, non-laboratory diagnostics, observation medicine, ophthalmology, sensitive examinations, primary decisionmaking within multidisciplinary teams, telemedicine, and transfers/ transitions of care.

Surveying Program Directors

To ensure the curriculum revisions reflected the broader EM community, the PRWG surveyed

289 emergency medicine program directors, achieving a 60% response. Results closely aligned with the curriculum the PRWG had developed independently, confirming similar priorities and elements.

At CORD 2025, some directors raised concerns about how survey results would be used. The survey introduction explained that responses were intended to inform the development of new program requirements, not to affect program accreditation decisions. That language was meant to reassure directors but instead caused confusion, with some questioning whether their input would actually