SAEM STAFF

Chief Executive Officer

Megan N. Schagrin, MBA, CAE, CFRE

Ext. 212, mschagrin@saem.org

Director, Finance & Operations

Doug Ray, MSA Ext. 208, dray@saem.org

Manager, Accounting

Edwina Zaccardo

Ext. 216, ezaccardo@saem.org

Director, IT

Anthony Macalindong

Ext. 217, amacalindong@saem.org

Specialist, IT Support

Dawud Lawson

Ext. 225, dlawson@saem.org

Director, Governance

Erin Campo

Ext. 201, ecampo@saem.org

Manager, Governance

Juana Vazquez

Ext. 228, jvazquez@saem.org

Director, Communications & Publications

Laura Giblin

Ext. 219, lgiblin@saem.org

Sr. Manager, Communications & Publications

Stacey Roseen

Ext. 207, sroseen@saem.org

Manager, Digital Marketing & Communications

Raf Rokita

Ext. 244, rrokita@saem.org

Sr. Director, Foundation and Business Development

Melissa McMillian, CAE, CNP Ext. 203, mmcmillian@saem.org

Sr. Manager, Development for the SAEM Foundation

Julie Wolfe

Ext. 230, jwolfe@saem.org

Manager, Educational Course Development

Kayla Belec Roseen Ext. 206, kbelec@saem.org

Manager, Exhibits and Sponsorships

Bill Schmitt Ext. 204, wschmitt@saem.org

Director, Membership & Meetings

Holly Byrd-Duncan, MBA Ext. 210, hbyrdduncan@saem.org

Sr. Manager, Membership

George Greaves Ext. 211, ggreaves@saem.org

Sr. Manager, Education

Andrea Ray Ext. 214, aray@saem.org

Sr. Coordinator, Membership & Meetings

Monica Bell, CMP Ext. 202, mbell@saem.org

Specialist, Membership Recruitment

Krystle Ansay Ext. 239, kansay@saem.org

Meeting Planner

Kar Corlew Ext. 218, kcorlew@saem.org

AEM Editor in Chief

Jeffrey Kline, MD AEMEditor@saem.org

AEM E&T Editor in Chief

Susan Promes, MD AEMETeditor@saem.org

AEM/AEM E&T Peer Review Coordinator

Taylor Bowen tbowen@saem.org aem@saem.org aemet@saem.org

2022–2023 BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Angela M. Mills, MD President

Columbia University, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Wendy C. Coates, MD President Elect

Los Angeles County HarborUCLA Medical Center

Members-at-Large

Pooja Agrawal, MD, MPH

Yale University School of Medicine

Jeffrey P. Druck, MD

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Julianna J. Jung, MD

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS Emory University

Ali S. Raja, MD, MBA, MPH Secretary Treasurer Massachusetts General Hospital / Harvard Medical School

Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD

Immediate Past President Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Ava E. Pierce, MD UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas

Jody A. Vogel, MD, MSc, MSW Stanford University Department of Emergency Medicine

Resident Member

Wendy W. Sun, MD Yale University School of Medicine

3 President’s Comments

SAEM’s 2023 Strategic Plan: Shaping the Future Science, Education, and Practice of Emergency Medicine

4 Spotlight

The SAEM Annual Meeting: Where Education and Science Converge – An Interview With SAEM23 Program Chair Ryan L. LaFollette, MD

8-17

23 Preview

18 Administration & Operations

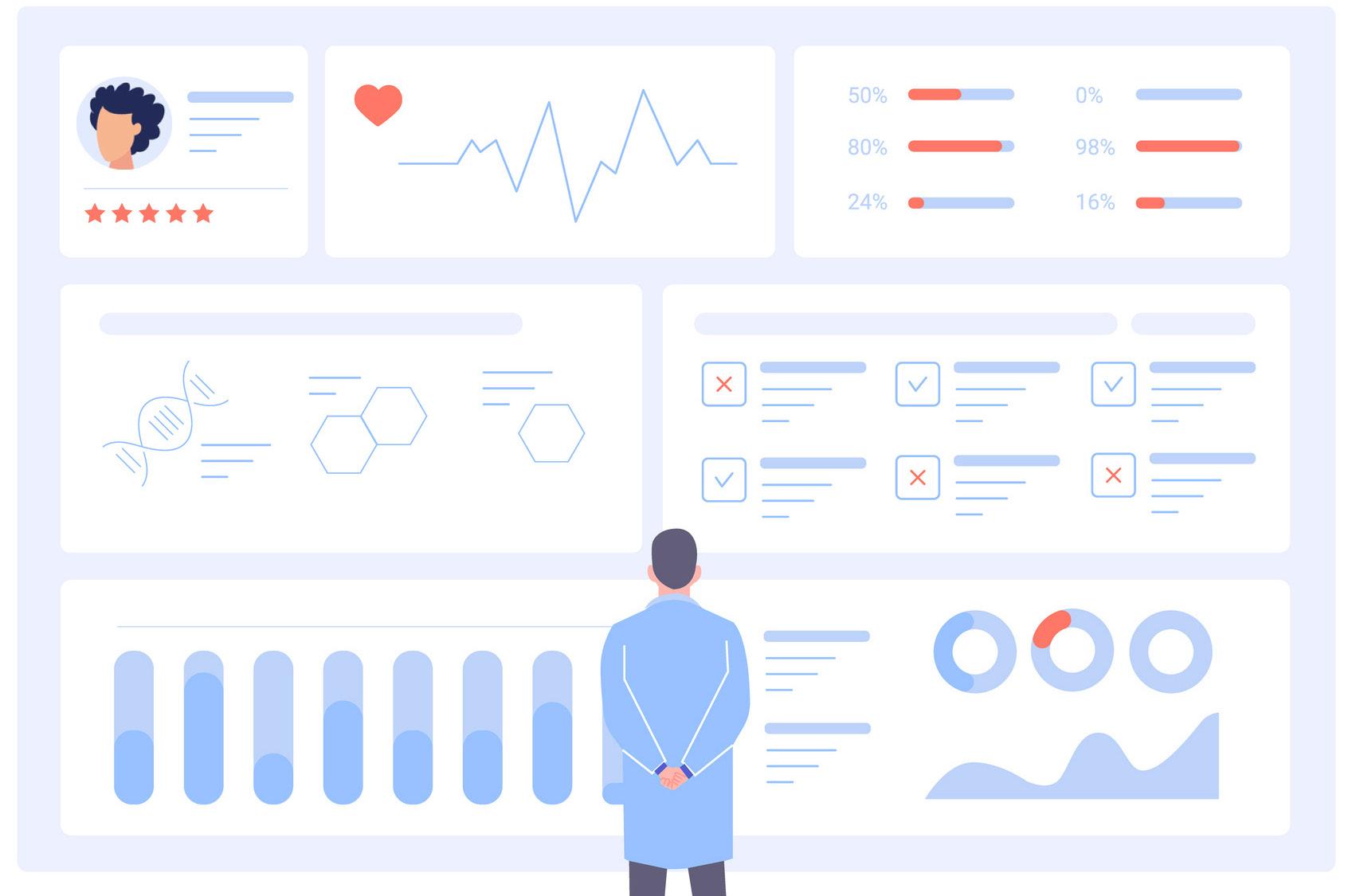

Health Equity Dashboards: A Key Driver Toward Equitable Patient Care

20 Diversity & Inclusion

The Impact of COVID-19 on Communication in the Health Care Setting for People With Disabilities

22 DEI Perspective

Reflections from the Twilight Zone: Navigating Medicine as a Nonbinary Medical Student

24 Education Hackschooling Residency Education

26 Ethics in Action A Difficult Foley

28 Geriatric EM Increasing Use of Cannabis Among Older Adults in the U.S. and Canada

30 Global EM

EMS Development in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Considerations for Improving Education Internationally

33 Global EM

Tigray, Ethiopia: The War May be Ending but the Challenges Facing Humanitarian Responders Are Immense

36 Innovation

The Power and Beauty of Design Thinking: 5 stages

42

The Challenges and Rewards of Creating Something Worthwhile

44 Research

Changing Practice in the Hospital Setting: A Tale of Two Teams

46

48 Sex & Gender in EM

50

54 Wellness

Moral Injury: What It Is and What We Can Do About It

58 Wellness

#StopTheStigmaEM: A Call to Action for EM Leaders

60 SAEMF Annual Alliance Donors Make Big Things Happen!

61 Why join the Annual Alliance?

62 Expressing Gratitude to the 2023 Annual Alliance and Legacy Society Donors

66 SAEMF Chairs' Challenge and Vice Chairs' Challenge

66 Briefs & Bullet Points

- SAEM News - SAEM Foundation

- Regional Meetings - SAEM RAMS

68 SAEM Reports

- Academy News: CDEM

PRESIDENT’S COMMENTS

Angela M. Mills, MD Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons 2022–2023 President, SAEMSAEM’s 2023 Strategic Plan: Shaping the Future Science, Education, and Practice of Emergency Medicine

Each January the SAEM Board of Directors convenes to finalize the annual strategies that will continue to move our SAEM Strategic Plan forward. These strategies are developed based on a compilation of meetings with members, mega issue discussions at the Board level, and multiyear plans that were previously developed. Goals and objectives have been developed to meet our SAEM mission (“To lead the advancement of academic emergency medicine through education, research, and professional development.”) and the SAEM Board works on specific strategies with measurable outcomes to meet these goals and objectives. In this article I will share several of these strategies to highlight some of the amazing work our members and staff will be engaging in this year.

Educational Goals

In alignment with SAEM’s standing as the premier organization for academic emergency medicine (EM) educational resources for both medical educators and learners, our 2023 strategies include launching a brand new, innovative faculty development cohort course, the SAEM Master Educators, which addresses core principles of medical education not covered in our other education-related courses. Last year the Emerging Leader Development (eLEAD) program was introduced, providing leaders in academic EM with a structured, longitudinal, year-long experience to develop foundational leadership skills, cultivate a meaningful career network, and build a bridge to countless opportunities in their field. This inaugural year will be evaluated with the second year being launched in

May at SAEM23. Speaking of our annual meeting, this event encompasses another significant annual strategy with attendance of well over 3,000 members and packed with incredible educational content and cutting-edge research.

Research Goals

Our SAEM research goal is to increase the impact, productivity, implementation, and visibility across the spectrum of emergency care research. Strategies include enhanced collaboration with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) on the goals and objectives of the Office of Emergency Care Research, as well as collaboration with other federal funding agencies, to promote networking, increased funding for our specialty, and enhanced funding strategies for our members. Additional strategies include assisting the SAEM Foundation in fundraising and grant funding for our members, making the largest research investment in academic EM’s future, and strengthening the Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department (GRACE) program, which addresses best practices for common chief complaints based on evidence-based research and expert consensus.

Personal & Professional Goals

SAEM strives to be an essential contributor to the personal and professional development of the academic EM community. Our professional development and support strategies include expansion and promotion of an online comprehensive DEI curriculum, promotion of mental health awareness to our members and the EM

community through continuation of the Stop the Stigma EM campaign, review and analysis of the membership survey, and development of an SAEM member recruitment and retention plan for our diverse faculty, residents, and students.

Workforce Goals

A new pillar for workforce development was added to the strategic plan last year specifically to define the evolving landscape and workforce of academic EM to address where SAEM can uniquely support dynamic changes in the workforce. Annual strategies for workforce include developing a comprehensive needs assessment to identify and inform best practices to attract talented and diverse students to EM that encompass the spectrum of academic practice.

SAEM is shaping the future science, education, and practice of emergency medicine. The amount of content being produced by our members and staff through our academies, committees, and interest groups is tremendous. I am excited to see the outcomes of the annual strategies and grateful for the great work by all of you to improve patient care, educate and mentor our learners, and produce impactful scholarship and research discovery to advance emergency care.

ABOUT DR. MILLS: Angela M. Mills, MD, is the J. E. Beaumont professor and chair of the department of emergency medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons and chief of emergency services for NewYorkPresbyterian –Columbia

THE SAEM ANNUAL MEETING: WHERE EDUCATION AND SCIENCE CONVERGE

An Interview With SAEM Annual Meeting Program Committee Chair Ryan L. LaFollette, MD

Ryan L. LaFollette, MD, is associate professor of clinical emergency medicine and assistant residency program director for the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. He also serves as a Cincinnati SWAT physician and is a flight physician with University of Cincinnati’s Air Care.

A native of New York, from a town just outside of Syracuse, Dr. LaFollette completed his medical training at Upstate Medical University followed by residency at the University of Cincinnati where he served as chief resident in the Class of 2016.

In addition to serving as the coeditor of the FOAMed site TamingtheSRU.com, Dr. LaFollette is actively involved with SAEM, having served previously on the SAEM Awards Committee, SAEM Education Committee, and as chair of the SAEM Virtual Presence Committee. He presently chairs the SAEM Annual Meeting Program Committee, on which he previously served as chair of the didactics subcommittee as well as in the Medical Student Ambassador (MSA) program.

Tell us a little about your journey to becoming SAEM annual meeting program committee chair. What led you to this point?

My introduction into SAEM follows a similar path as many of my colleagues. I was brought into the organization during my second year of residency by one of my attendings, Andra Blomkalns, a former SAEM Program Committee Chair and an SAEM past president. Early in my SAEM career, while working with and developing the Medical Student Ambassador (MSA) program, I was exposed to excellent mentors like Drs. Gillian Beauchamp and Ali Raja. After handing the MSA program off to the talented Dr. Riley Grosso, I chaired the SAEM Program Committee Didactics Subcommittee for several years before assuming my current role as program committee cair. I have also been privileged to serve on the SAEM Awards Committee, SAEM Education Committee, and as chair of the SAEM Virtual Presence Committee, during which I led the expansion of streaming options for the annual meeting.

What does serving as the annual meeting program committee chair mean to you?

I continue to be humbled by the talent and dedication of SAEM Program Committee members and staff who make this amazing meeting happen. The opportunity to work with a group of people from around the country dedicated to making our annual meeting a first-rate experience has been a highlight. I love being a part of helping the leaders in our organization find the best ways to showcase the work that SAEM members do all year long.

What unique qualities do you bring to the table as the annual meeting program committee chair?

The integration of science and educational content is a hallmark of the SAEM Annual Meeting and the focus on delivering both

education and clinical science is a unique characteristic that sets SAEM apart. As an assistant program director and FOAMed curator, I am happy to bring my educational lens to that intersection. The work our members do all year is so impressive and I hope I can help ensure that everyone has an opportunity to engage with our members in the most effective way possible.

What excites you the most about this year’s event? What are you most looking forward to at SAEM23?

We have just selected our keynote speakers and I have to say I am very excited! They represent an exciting cross-section of our specialty and what it will become. Dr. Jane Scott will kick off our plenary presentations with the Dr. Peter Rosen Memorial Keynote Address and Dr. Susan Promes will deliver our Wednesday Medical Education Keynote. With so many of our academy and RAMS events spread out across Austin, I am also excited for people to have the opportunity to explore this amazing city. Lastly, I am excited that we can include parents more wholly during this year’s meeting with our Onsite Childcare/Day Camp. (If you’re interested, register by March 14!)

How will you personally measure the success of SAEM23?

I am excited by the successes we have already had in preparing for the meeting! This year we received a record number of didactics, IGNITE!, and innovations submissions, which makes me hopeful that we might break attendance and engagement records as well. I am excited to meet members who have never attended an SAEM Annual Meeting, learn what engages them the most and how we can continue this momentum into Phoenix in 2024!

continued on Page 6

Dr. LaFollette teaching morning report to Isaac Shaw, MD at the beginning of a clinical shift“The integration of science and educational content is a hallmark of the SAEM Annual Meeting and the focus on delivering both education and clinical science is a unique characteristic that sets SAEM apart.”

continued from Page 5

I’m sure you’ve attended other conferences throughout your career; what makes the SAEM Annual Meeting stand out from the rest?

The level of presentation at the SAEM Annual Meeting is what sets it apart. There is no question in my mind that if you walk into a room at SAEM23 there will be something to be gained whether you are a medical student or a senior faculty. There are more opportunities to network at the SAEM Annual Meeting than at any conference I have been to. Our meeting combines all the benefits of a large conference with the intimacy of a community. And this community comes to our annual meeting with an eye toward connecting, networking, and building the next generation of academic leaders. You can’t get that at any other conference.

Why is the SAEM Annual Meeting a “must-attend” event of the year for academic EM professionals and what can they expect to take away from this event?

The SAEM Annual Meeting is a must-attend event for the people who comprise academic EM. You can read the articles and practice the medicine all year, but to engage with the authors who wrote the articles and interact with colleagues across the academic spectrum comes but once a year and this year it will be in May in Austin. Everyone, no matter at what level of their career, should expect to take away a new mentor or mentee, research idea, and very full mind (and belly).

What is your advice to first-time attendees for making the most of SAEM23?

Come prepared! On your drive/flight/uber to the meeting, review the program planner, pick out workshops, didactics, abstracts, and events that are interesting to YOU and add them to your program planner schedule and app. Don’t just attend what your colleagues or friends are attending but build a schedule full of things that fit your vision of the clinician/ educator/researcher you want to be. Attend a session or event led by a presenter you’ve been interested to meet and chat with. All our faculty and presenters are open and interested to talk to you about how their work can connect with yours. And stop by dodgeball, as it will give you a new and enduring view of the skillset of the SAEM Board of Directors!

What makes Austin such a great city for this year’s annual meeting?

Whether you like country music and live music shows or are a blasphemous northerner like myself and enjoy coffee and microbreweries, you’ll find it all in this friendly, vibrant, up and coming city. Be sure to check out the bats at sunset on the

“Our meeting combines all the benefits of a large conference with the intimacy of a community.”

Congress Avenue bridge, take a run on the boardwalk of Lady Bird Lake, and see a show at one of the 250 live music venues.

SAEM is making great strides in addressing issues related to DEI. How does this come into play in a lasting way at the SAEM Annual Meeting?

We continue to take strides in diversity, equity, and inclusion along with the SAEM Board and other SAEM academies and committees by acknowledging bias and studying the makeup of

Up Close and Personal

those delivering the content as well as those grading it. We have taken steps to ensure the diversity of our plenaries and sessions reflect that of our society and have reallocated spaces to ensure that everyone who wants a seat in a meeting has one. Also by making sure the next generation of leaders—our medical student ambassadors—have the opportunity to be exposed to SAEM and its leaders through the awarding of a SAEM RAMS Diversity and Inclusion MSA Scholarship.

Name three people, living or deceased, whom you would invite to your dream dinner party.

1. Chef and travel documentarian Anthony Bourdain for his attitude toward engaging and appreciating others

2. Landscape photographer Ansel Adams for his technical gifts and efforts to share a vision of wilderness with another generation

3. My grandmother for her love of travel and people

What's the one thing few people know about you?

I am a lifelong vegetarian and have never eaten meat — and I am still alive 36 years later! (Although I am also a living warning that healthy eating and vegetarianism are two circles of a Venn diagram that do not entirely overlap!)

What is your guiltiest pleasure (book, movie, music, show, food, etc.)? Running. It takes time away from many things I should be doing — but it cannot be replaced!

Please complete these three sentences: In high school I was voted… most spirited. I wish I was kidding. A song you’ll find me singing in the shower is… No songs, but I appreciate how waterproof the iPhone is because that is quality audiobook time.

AUSTIN, TX • MAY 16-19, 2023 PREVIEW

Austin is Waiting to Welcome You to SAEM23!

A Message From Ryan LaFollette, MD, SAEM23 Program Committee Chair

Create Your Perfect Playlist

Just as music is a huge part of Austin's DNA, education and research are part of SAEM’s strong legacy and what makes our annual meeting THE premier event in academic emergency medicine. We invite you to create an SAEM23 soundtrack that’s all your own, by compiling a playlist from hundreds of sessions, including:

• More than a dozen half- and full-day workshops that aim to strengthen knowledge and skills in specific topic areas

• Dynamic didactics from the best minds in academic EM

• High-quality, cutting-edge research

• Ground-breaking, practice-changing plenary sessions

• Two keynote addresses by renowned speaker-influencers

• Focused educational forums that offer something for everyone, from seasoned faculty to medical students just starting their careers

• Educational and gamified experiential learning competitions like SimWARs and Sonogames®

Nothing Beats Being Together

SAEM annual meetings are renowned for the expansive networking events and career development opportunities they offer. Connect in person with your contemporaries and take advantage of opportunities like Speed Mentoring, Speed Mentoring for Educators, and the Residency & Fellowship Fair to talk to peers, leaders, and others who can help you take your career to the next level.

Say Hello to Our EM Pharmacy Friends!

SAEM is excited to announce that our emergency medicine pharmacy colleagues will in the house with us for the EMPoweRx (Emergency Medicine Pharmacotherapy with Resuscitation) Conference — a hybrid conference that presenting the latest resuscitation, emergency medicine pharmacotherapy, and administrative issues that are unique to the ED.

A Focus on YOU

We like to think of SAEM as a family, and in that spirit we are providing family-centric annual meeting services such as on-

site childcare (sign up ends March 14!) and a private “family room” equipped with everything to meet the needs of baby and parent(s).

A Texas-Sized Welcome

Once you've eaten your weight in barbecue, heard a band that's this close to blowing up, and slammed a Lone Star or two at the city’s hottest honky tonks, you’ll understand why Austin is not only one of America’s the fastest-growing and best cities to visit, it’s also the perfect place to hold an annual meeting that promises to be as big-hearted and boast-worthy as the state of Texas.

The Lone Star State's shining capital is waiting with open arms to welcome you and so are we! On behalf of the Program Committee and SAEM leadership, we can’t wait to see you in Austin!

Register by March 14 to secure your early bird discount!

Announcing the Top 8

Plenary Abstracts

Abstracts present research data, including study background and methodology, research limitations and results, and the conclusions/significance of the study. Abstract session lengths vary depending on the presentation type: plenary (15 minutes), full oral (12 minutes), lightning oral (eight minutes), ePoster (seven minutes). The SAEM23 Program Committee is pleased to announce the top eight abstracts selected to be presented during special plenary sessions to be held immediately following the keynote addresses on Wednesday and Thursday. These eight abstracts were chosen as the best from among 1200+ submissions.

Opening Session Plenaries

Wednesday, May 17, 10:00 AM – 11:00 AM CT

1. Erector Spinae Plane Block for Low Back Pain Reduces Pain and May Reduce Opioid Consumption

Andrew Wayment, Robert Steele, Jacob Avila, Ryan Itoh

2. Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act Citations for Failure to Accept Appropriate Transfer, 2011-2022

Jasmeen Randhawa, Genevieve Santillanes, Sameer Ahmed, Zachary Reichert, Katie Hawk, Sarah Axeen, Jesse Pines, Seth Seabury, Michael Menchine, Sophie Terp

3. Emergency Medicine Workforce Attrition Differences by Age and Gender

Cameron Gettel, D Mark Courtney, Pooja Agrawal, Tracy Madsen, Arjun Venkatesh

4. Derivation of a Clinical Decision Rule to Guide Neuroimaging in Older Adults Who Have Fallen

Kerstin de Wit, Mathew Mercuri, Natasha Clayton, Éric Mercier, Judy Morris, Rebecca Jeanmonod, Debra Eagles, Catherine Varner, David Barbic, Ian Buchanan, Mariyam Ali, Yoan Kagoma, Ashkan Shoamanesh, Paul Engels, Sunjay Sharma, Andrew Worster, Shelley McLeod, Marcel Émond, Ian Stiell, Alexandra Papaioannou, Sameer Parpia View full abstracts.

Dr. Jane Scott, Pioneer and Advocate for Research Funding and Training in Emergency Care to Present Dr. Peter Rosen Memorial Keynote Address

Jane Scott, ScD, MSN, renowned and respected for her work as a leader in emergency medicine research funding and training, will present the SAEM23 Dr. Peter Rosen Memorial Keynote Address, “Advancing Emergency Care Research: Reflecting on Our Past, Looking to Our Future,” from 9:30-10 a.m. on Wednesday, May 17 during the SAEM23 opening session.

Dr. Scott began her career in the emergency care setting as a staff nurse at the Duke University Emergency Department and then as a nurse practitioner at the Johns Hopkins adult emergency department. She presented her first research abstract in 1981 at the University Association of Emergency Medicine meeting, which was followed by numerous emergency care publications. After obtaining a doctorate from Hopkins School of Public Health, Dr. Scott joined the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) as a program officer providing oversight to federally funded prehospital and ED studies. In 1995 she joined the University of Maryland National Study Center for Trauma and EMS followed by serving as research director of the program in trauma at the R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center. In 2005 Dr. Scott joined the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as director of the Office of Research Training and Career Development, Division of Cardiovascular Sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). In 2008 she created the NHLBI K12 program in emergency care research, which she managed until her retirement, working extensively with the emergency medicine researchers at the eight training programs that have trained over 50 K12 scholars.

Dr. Scott has served on the SAEM Research Committee, ACEP-SAEM Federal Research Funding Workgroup, and as faculty at the EMF-SAEMF Grantee Workshop for over eight years. She has educated and mentored countless SAEM members on the K12 programs, presented at numerous SAEM annual meetings, worked closely with program officers on NIH-related matters, and taught many of our investigators how to become independently funded

Dr. Susan Promes, Leader in Emergency Medicine Education, to Present the Education

Keynote Address at SAEM23

Susan Promes, MD, MBA, editorin-chief of Academic Emergency Medicine Education and Training journal, and a recognized leader in emergency medicine education, with 25 years of experience, will present the SAEM23 Education Keynote Address, “Perspectives in Medical Education: Past Experiences, Future Possibilities,” on Thursday, May 18 from 9:30-10 a.m.

Dr. Promes is a tenured professor at Penn State University Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and has served as chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine since 2014. Prior to 2014, she spent seven years at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) where she served as vice chair for education, emergency medicine residency program director, and director of curricular affairs in the graduate medical education office. Additionally, Dr. Promes was the inaugural emergency medicine residency program pirector at Duke University and director of the medical school capstone course.

Promes, a graduate of Washington University in St. Louis, Mo., earned her medical degree from Penn State College of Medicine and did her residency training at Alameda County Medical Center, Highland General Hospital where she served as chief resident.

She is course director for the American College of Emergency Physicians Teaching Fellowship and the inaugural editor-in-chief of Academic Emergency Medicine Education and Training, a journal dedicated to medical education scholarship in emergency medicine which debuted in 2017.

Her scholarly work has centered around topics germane to emergency medicine medical education and clinical guidelines for the practicing emergency physician. In addition to many peer review publications, she has edited multiple McGraw Hill board review books to prepare physicians for the emergency medicine board exam.

An internationally recognized leader in academic EM, Dr. Promes has received numerous awards and honors for excellence in teaching, leadership, and service. She is a graduate of the UCSF Teaching Scholars Program, a member of the UCSF Academy of Medical Educators, and the recipient of the Academy’s Teaching Excellence Award. In 2020 she received the SAEM Hal Jayne Excellence in Education Award and is also the recipient of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Courage to Teach Award.

Thursday Session Plenaries

Thursday, May 18, 10:00 AM – 11:00 AM CT

5. Emergency Medicine Bound Fourth-Year Medical Student Performance on a Standardized Substance Use Disorder Patient Case

Tomohiro Ko, Amanda Esposito, Brennan Cook, Archana Pradhan

6. Facilitating Adaptive Expertise in Learning Computed Tomography: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial

Leonardo Aliaga, Rebecca Bavolek, Benjamin Cooper, Amy Mariorenzi, James Ahn, Aaron Kraut, David Duong, Michael Gisondi

7. Geographic Distribution of Emergency Residency Training in Medically Underserved Areas and Current Practice

Mary Haas, Laura Hopson, Caroline Kayko, John Burkhardt

8. Data-Driven Learning: Understanding How Medical Students Utilize a Data Dashboard

Daniel Owens, David Scudder, Wendy Christensen, Rachael Tan, Tai Lockspeiser View full abstracts.

SAEM23 Abstracts

SAEM Annual Meeting abstracts represent the work of thousands of researchers and educators who have created new knowledge and thinking about emergency care that adds valuable confirmation of previous work, presents evidence that might change the practice of EM emergency medicine for the better, and elevates the outcomes and experiences of every patient who seeks emergency medical care. Collectively they reflect a global experience of emergency care that together tell the story of important challenges and the need for more knowledge.

· Plenaries, May 17 and 18, 2023

· Orals, May 17 and 18, 2023

· Lightning Orals, May 17-19,

· ePosters, May 17-19, 2023

Educational Sessions

Advanced EM Workshop Day

Tuesday, May 16, 8:00 AM – 5:00 PM CT

Advanced EM Workshops are intensive educational sessions that focus on techniques, skills, and practical aspects of the specialty. This year’s Advanced EM Workshop Day offerings includes 18 half- and full-day sessions that cover specialized areas in emergency medicine and strengthen knowledge and skills in specific topic areas. Add any workshop when you register for SAEM23

Full-Day Workshops

• Bringing the Outside In: Incorporating Wilderness Medicine Into Your Curriculum

• EMPoweRx Conference

• Grant Writing Workshop

• SAEM23 Consensus Conference

• World Health Organization Basic Emergency Care Training of Trainers

Half-Day Morning Workshops

• Beyond Microaggressions: Upstander Training for Allyship

• Clerkship Directors Bootcamp

• Emergency Department Operations On-Ramp: A Crash Course

• Medical Education Research Bootcamp

• Simulation Hacks: Building and Validating Do-it-yourself Models

• Ultrasound-guided Nerve Block

Half-Day Afternoon Workshops

• Be the Best Teacher: Medical Education Bootcamp

• Become an Excellent Peer Reviewer

• Developing Effective Education for the Next Generation

• Figuring Out Fiberscope

• Not Your Mother’s Ethics Course: Teaching Medical Ethics

• Virtual Reality Training in Mass Casualty Response

• Vice Chairs Workshop

Featured Workshop

The 2023 Consensus Conference— Precision Emergency Medicine: How Data Science, -Omics, and Technology Will Transform Emergency Medicine

Wednesday, May 16, 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM CT

Precision emergency medicine is the purposeful use of big data and technology to deliver acute care safely, efficiently, and authentically for individual patients and their communities. Advances in health technology and data science offer emergency physicians the ability to individualize patient care and improve the health of local communities. However, most emergency providers are less familiar with precision medicine and how this new paradigm will transform the practice of emergency medicine. Research is needed to understand how to best implement precision emergency medicine in an effective and equitable manner. Join us for this year’s consensus conference — Precision Emergency Medicine: How Data Science, -Omics, and Technology

Will Transform Emergency Medicine — as we explore the research opportunities, implementation, ethics, and patient outcomes of precision emergency medicine.

Didactics

Wednesday May 17, 12:00 PM – 5:20 PM CT

Thursday, May 18, 8:00 AM – 5:20 PM CT

Friday, May 19, 8:00 AM – 12:50 PM CT

Didactics are presentations that are designed to teach on a particular subject and can vary in structure from lecture and flipped classroom formats to panels and small group discussions. 156 innovative and interactive sessions cover a range of educational topics in key categories, including: administrative, career development, education, clinical, research.

General Information

Taking place May 16–19, 2023, SAEM23 will be held in Austin, Texas. With more than 1,000 educational sessions, presentation opportunities, and valuable networking, you won’t want to miss this essential event. These links will help you navigate the general information you need to know.

• Pricing and Registration

• Schedule-at-a-Glance

• Program Planner

• Onsite Childcare/Day Camp

• FAQ

• Accessibility

• COVID-19 Policy

• For International Travelers

• Affiliated Meeting Space Request

• Social Media Best Practices

IGNITE!

Wednesday, May 17, 11:00 AM – 12:50 PM CT

Friday, May 19, 10:00 AM – 11:50 AM CT

IGNITE! talks are fast paced, highly energetic, captivating, and engaging presentations on a variety of topics. The IGNITE! format is five minutes in length with 20 auto-advancing slides. A panel of judges selects a “Best of IGNITE!” winner from each IGNITE! session. An “Audience Choice Award” is also given at each session based on audience polling. All topics are accepted. Speakers in the past have talked about their experiences in disaster relief, waxed poetic about the role of machine learning in emergency medicine and challenged core practices in EM critical care and education.

Innovations

Thursday, May 18, 11:00 AM – 4:00 PM (Tabletop)

Thursday, May 18, 11:00 AM – 5:00 PM (Orals)

Friday, May 19, 8:00 AM – 9:50 AM

Innovations present novel ideas, new products, innovative procedures, and unique approaches in medical education, faculty development, wellness, operations, and patient care. Innovations are presented in either a seven-minute oral presentation or as a tabletop/hands-on demonstration.

Forums

SAEM Leadership Forum

Tuesday, May 16, 8:00 AM – 5:00 PM CT

SAEM Leadership Forum is designed for all levels of aspiring leaders who are interested in improving their leadership skills. The session will provide exposure to core leadership topics with an emphasis on experiential learning and practical

application. Presenters are recognized experts with extensive leadership experience. The agenda includes segments on emotional intelligence and its impact on leadership style, strategies for successful leadership, increasing visibility, and managing conflict. Add any forum when you register for SAEM23.

Junior Faculty Development Forum

Tuesday, May 16, 8:30 AM – 4:15 PM CT

Junior Faculty Development Forum is designed to enable junior faculty to engage with senior leaders in the field; develop strategies for promotion, productivity, and academic advancement; and become the next generation of academic emergency medicine faculty leaders. The forum is intended for fellows and early-career faculty who have recently secured faculty positions within academic emergency departments. presentations from leaders in emergency medicine administration, education, and research. Add any forum when you register for SAEM23.

Chief Resident Forum

Thursday, May 18, 8:00 AM – 3:00 PM CT

Chief Resident Forum gathers chief residents from around the nation to discuss traits of effective leaders, network with peers, and get a crash course on keeping their residencies thriving. Engaging sessions by national leaders will emphasize the practical aspects of being a chief resident, including optimizing resident schedules, developing innovative curricula, recruiting the program’s next generation, and balancing wellness with leadership. Add any forum when you register for SAEM23

Medical Student Symposium

Thursday, May 18, 8:00 AM – 3:00 PM CT

Medical Student Symposium serves as an overview of emergency medicine (EM) and the application and match process for applicants of allopathic, osteopathic, international, and military backgrounds. In this day-long session, thought leaders in the specialty discuss the process of applying for an EM residency position. The session includes specific discussions about clerkships, away rotations, personal statements, the match process, and interviews. Ample time is provided for questions and discussions during a lunch with EM program directors and clerkship directors. Add any forum when you register for SAEM23

Career Building

Opportunities

Residency & Fellowship Fair

Thursday, May 18, 3:00 – 5:00 PM CT

Speed Mentoring

Wednesday, May 17, 3:30 PM – 5:20 PM CT

The SAEM Residency & Fellowship Fair lets you explore residency and fellowship programs from across the nation, all under one roof. Meet with representatives from dozens of coveted programs, all waiting to talk to you about their programs and give you advice to help you with the application process. Connect with current residents and fellows to ask questions and get valuable advice and encouragement to help you navigate the next steps of your career. This event is free for residents and medical students, so take advantage of the opportunity to visit with as many programs as time allows!

Residency and Fellowship Directors!

The SAEM Residency & Fellowship Fair is an important and prominent event in the annual emergency medicine application cycle, giving institutions the opportunity to showcase their residency and fellowship programs to hundreds of medical students and emergency medicine residents looking to find their perfect residency or fellowship. Don’t miss this convenient, cost-effective, recruiting opportunity.

Speed Mentoring for Medical Educators

Thursday, May 18, 11:00 AM – 11:50 AM CT

Speed Mentoring for Medical Educators offers faculty an opportunity to engage in short discussions with mentors who have expertise and significant experience in medical education. Participants will have an opportunity to sample potential mentoring relationships and identify a medical education mentor whose experience and personality aligns with their professional interests, desired career trajectory, and personality traits.

Mentors needed!

If you are interested in serving as a mentor, sign up when you register for the annual meeting.

Speed Mentoring matches resident and medical student mentees into small groups of 5-10 attendees who share their interests for quick-fire, 10-minute mentoring sessions. Participants will have an opportunity to start new mentoring relationships with mentors from around the country as well as socialize with fellow residents and medical students. Add this event to your annual meeting registration at no additional cost! Mentors needed!

If you are interested in serving as a mentor, sign up when you register for the annual meeting.

Featured SAEM Academy Events

• Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine and Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine Luncheon

• Association of Academic Chairs in Emergency Medicine Annual Reception and Dinner

Accepting “In Memoriam”

Submissions

This spring, at SAEM23 in Austin, TX, we will pause to remember our SAEM friends and colleagues who left us during the past year.

We are seeking the names of individuals who have passed away since April 1, 2022 for an “In Memoriam” video tribute to be shown during the SAEM23 opening session. Please send your “In Memoriam” submissions (name, institution, and a photo) to Stacey Roseen at sroseen@saem.org by April 3, 2023.

SAEM23 Exhibit Hall

Exhibit Hall Hours

All of the following events take place in the SAEM23 exhibit hall.

Tuesday, May 16

5:00 PM - 6:00 PM CT

Kickoff Party

Wednesday, May 17

7:00 AM - 9:00 AM CT

Exhibit Hall Open

7:00 AM - 8:00 AM CT

Networking Coffee Service

12:00 PM - 1:00 PM CT

Light Lunch

12:00 PM - 4:00 PM CT

Exhibit Hall Open

Thursday, May 18

7:00 AM - 1:00 PM CT

Exhibit Hall Open

7:00 AM - 8:00 AM CT

Networking Coffee Break

12:00 PM - 1:00 PM CT

Light Lunch

Sponsors

and Exhibitors

— There Are 3,500 Reasons Why You Should Exhibit at SAEM23!

Each year at the SAEM Annual Meeting, emergency medicine’s most brilliant minds, from some of the country’s most prestigious medical schools and teaching institutions, gather for the presentation of cutting-edge research and educational content and to learn about the latest innovations in products and services. This year, at SAEM23, May 16-19, in Austin Texas, we’re expecting a record 3,500 of these EM thought leaders, innovators, and early adopters and we invite you to reserve your exhibit booth today for an opportunity to meet them face-to-face!

We’ll help you maximize your exhibitor experience with…

• Events hosted inside the exhibit hall to drive more attendees to your booth, including our popular kickoff party

• Add-ons and upgrades to increase your visibility, such as a bigger booth or improved booth location

• Sponsorship opportunities to generate positive PR, including satellite symposia and our famous dodgeball tournament

Add-ons to increase your exposure to all SAEM23 attendees:

• Exhibitor bingo! - $500

• Bigger booth upgrade - $3,050

• Corner booth upgrade - $500

• Silver booth upgrade - $350

• Gold booth upgrade - $850

View the SAEM23 Exhibitor Prospectus for all the details. Still have questions? Email Bill Schmitt, manager, exhibits and sponsorships, or call (847) 257-7224.

Team Activities

Simulation Academy SimWars

Wednesday, May 17, 1:00 PM – 5:00 PM CT

SonoGames®

Friday, May 19, 8:00 AM – 1:00 PM CT

Simulation Academy SimWars is the premier national simulation competition for emergency medicine residents. Created and brought to you by the SAEM Simulation Academy, SimWars is a simulation-based competition between teams of clinical providers that compete in various aspects of patient care in front of a large audience. This type of learning emphasizes experiential learning, which involves the learner in the moment, mentally, physically, and emotionally in the moment, whether a simulated experience, reliving the past, or through collaboration (community of practice). Additionally, SimWars offers learning opportunities for those watching and instructing, as every person involved can benefit from observing and reflecting on decision making, as well as viewing and discussing practice variations across disciplines and institutions. SimWars combines a grouplearning format with individual skill assessment to enhance global knowledge and skill performance.

Dodgeball

Thursday, May 18, 5:30 PM – 7:30 PM CT

SonoGames® is a national ultrasound competition in which emergency medicine (EM) residents demonstrate their mad skills and knowledge of point-of-care ultrasound in an exciting and educational format. Don’t miss the winner-take-all, no-holds-barred action as teams of over 300 emergency medicine residents in crazy costumes battle it out in front of hundreds of spectators to prove they have mastered the “SonoSkills” to become SonoChamps and take home the SonoCup. Team registration closes May 1, 2023.

Reserve Your Lodging by April 22 for the Best Rates!

Join us for Dodgeball 2023, as we transform a basic ballroom into THE most amazing dodgeball court ever, complete with bleachers, hot dogs, cold suds, and cheering fans! This grownup twist to the classic playground game pits emergency medicine residency teams from all over the country in an epic battle to the finish and the right to call themselves dodgeball champs. Limited spots are available, so pull your team together soon and sign up for an opportunity to dodge, duck, dip, dive...and dodge to victory! Team registration is now open.

The JW Marriott Austin, 110 East 2nd Street, Austin, Texas, is the official host hotel for meetings, educational sessions, and several social events at SAEM23, May 16-19. Book online by 5 p.m. local time, April 22, 2023 to receive the special SAEM room block rate of $279 for single or double occupancy. A valid major credit card is required to hold a room. Space is limited and rates are available on a first-come, first-served basis. Additional housing is available at the Austin Marriott Downtown, 304 East Cesar Chavez Street (just one block away from our host hotel) and rooms may be reserved online

RAMS @ SAEM23: The “Can’t Miss” List

Expand Your Network

Connect with peers, leaders, and others who can help you take your career to the next level.

Didactics

SAEM23 offers more than 150 didactic sessions on wideranging topics. These innovative and interactive presentations are designed to teach on a particular subject and can vary in structure from lecture and flipped classroom formats to panels and small group discussions. For full descriptions, search for any of the titles below in the “Didactics” section of the SAEM23 Program Planner.

• A Fun Acting and Theater-Focused Didactic to Improve Connectedness With Yourself and Your Patients

• Key Concepts in Operations and Management: A Primer for Residents, Medical Students, Fellows, and Early Career Faculty

• Exploring the Evolving Landscape of Resident Unionization

• Firearm Injury Prevention From the Bedside

• Speed Mentoring

• Cocktails with Chairs

• Residency and Fellowship Fair

• AWAEM and ADIEM Luncheon

• RAMS Party at Maggie Mae’s

Join In Some “Friendly” Competition

Don’t miss these energetic, experiential learning competitions!

• SonoGames®

• Dodgeball

• SimWars

• SAEM RAMS Austin Scavenger Hunt

Explore Cutting-Edge Education Forums

Educational forums focus on leadership skills and practical applications for all career stages, with two developed especially for medical students and residents:

• The Emergency Medicine Job Market: Putting the 2020 Workforce Report Into Perspective

• Taking Your Didactics to the Next Level: Best Practices in Didactic Design

• What’s Your Cup of Tea? An Interactive Infusion of Leadership Skills for Women, Learner Edition

• Making the Most of Your SAEM Membership

• Thinking about a Fellowship? What Residents Need to Know

• Early Career Planning: Avoid Pitfalls and Achieve Success for Residents and Junior Faculty

• Too Much Good Stuff: When, Why, and How To Say No

• Emergency Medicine 2068: Divining the Future of Anyone, Anything, Anytime Medicine

• The Art of Asking Questions as a Gateway to Effective Feedback

• Allyship and Advocacy in #SoMe: Amplifying Voices

• Promote Yourself: Writing Strong Letters

• Outside-In and Inside-Out: Incorporating Wilderness Medicine into Medical Education

• Challenging Conversations When Time Is (Always) Tight: 3 Communication Frameworks to Use in a Pinch

• The FOAM Showcase

• Making Sense of All Those Numbers in Research Papers

• Best Practices for Ensuring High Quality Care for Incarcerated Patients: Patients’ Rights and Our Responsibilities

• Emergency Medicine in the Post-Roe Era: Emergency Department Management of Abortions

• Medical Student Symposium

• Chief Resident Leadership Forum

Advanced EM Workshop Day

Choose from among 18 full- and half-day educational sessions that focus on techniques, skills, and practical aspects of emergency medicine and strengthen knowledge and skills in specific topic areas. Here are a few to consider adding to your agenda:

• Figuring Out Fiberscope

• Ultrasound-guided Nerve Block

• SAEM Grant Writing Workshop

• Beyond Microaggressions: Upstander Training for Allyship

• The Dobbs Decision and the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act Implications for the Emergency Physician

• Pearls and Pitfalls of Rapid Goals of Care Discussions in the Emergency Department

• Stand Up! An Introduction to Upstander Training to Address Microaggressions in the Emergency Department

• Data Sources in Emergency Medicine: How to Leverage Existing National Datasets for Your Research Projects

This list was compiled by Hamza Ijaz, MD, president of RAMS and Wendy Sun, MD, past president of RAMS and resident member of the SAEM Board of Directors.

RAMS Party at Maggie Mae’s

Thursday, May 18, 10:00 PM – 2:00 AM

Join us for the SAEM social event of the year: The RAMS Party! Nobody throws a party like SAEM’s residents and medical students (RAMS) and nowhere is there a better place in Austin for a party than the legendary Maggie Mae’s on iconic Sixth Street. As the oldest locally owned venue in the heart of the Historic Entertainment District, Maggie Mae’s on Sixth Street has been serving up tunes since 1978 and is one of the reasons Austin is known as “The Live Music Capital of the World.” Maggie Mae’s is being spruced up to showcase her original charm and historic beauty while giving her a fresh, fun, and trendy vibe. She’ll be refreshed and ready to host all y’all on May 18, so put on your dancing boots and Stetson hat and plan to join us. Everyone is invited to the party, but our special VIP tables are limited and go fast, so if you’re interested you should reserve a table real soon!

ADMINISTRATION & OPERATIONS

Health Equity Dashboards: A Key Driver Toward Equitable Patient Care

By Marquita S. Norman, MD, MBA, Meagan Hunt, MD, Aaryn Kelli Hammond, MD, and Ryan Tsuchida, MD, on behalf of the SAEM ADIEM Operations Committee and the SAEM ED Administration and Clinical Operations CommitteeHealth care has made great strides in quality improvement incorporating lessons from industries including manufacturing and aviation. While many cite the 2001 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report as having “groundbreaking” or “practice changing” impact, not all areas of the report have been incorporated similarly. In this report IOM established six aims of health care quality captured in the acronym STEEEP (safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patientcentered). Institutional interventions and efforts to provide safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, and efficient care are typically both abundant and highly visible. Two decades following this report, more attention is needed toward the aim of equitable care. A recent ACEP workgroup report highlighted the need for integrating and reimagining quality outcomes in care to promote institutional accountability to overcome health care disparities. Here, we report how these

quality metrics can be presented and organized using dashboards.

While negative social determinants of health and a variety of structural challenges contribute to the health outcome of patients, so do the practices and policies within a given health system. Disparities in health care delivery have primarily been described using large databases supported by research projects. Less common is the approach for individual hospitals to monitor their own performance on care delivery to detect potential disparities and, in turn, use an equity lens in designing interventions. Institutional process measures designed to address disparities that rely on inpatient resources and interventions may not effectively address disparities experienced by patients solely cared for in the emergency department (ED). To truly assess whether we are providing

equitable care at the level of the emergency department, we will have to go deeper.

At least anecdotally, health care systems are increasingly focused on addressing health care disparities experienced by patients. The best practices to address these disparities remains an area of active research; however, many institutions are already deploying tools such as health equity dashboards to define where opportunities to reduce health care disparities exist. With the COVID-19 pandemic came a desire for rapid health care data visualization and public transparency. This led to a surge in the availability of dashboards to provide summary-level data, often with figures and graphs, to aid interpretation. Dashboards have been used for years to track health outcomes, process metrics (wide ranging from timely antibiotics for

sepsis, hand washing in patient rooms, and utilization of time outs before invasive procedures), and clinical operations (including hospital capacity, anticipated discharges, and PPE utilization). In this context, it is not surprising that equity dashboards are now being proposed to aid health care leaders in addressing health care disparities.

The greatest argument for a health equity dashboard centers on the principle that problem identification and planned interventions require the availability of data to describe gaps, set aims, and allow for continued evaluation of interventions. The barrier to creating these dashboards is greatly offset by the existing quality infrastructures built within each health care system. For example, the data source (often an EMR), data analytics, and technical support all rely on existing structures. In practicality, the intervention requires the additional stratification of outcomes by various demographic identifiers known locally or regionally to impact health care disparities.

When creating these dashboards, it is important to identify key stakeholders. While a comprehensive list would require individualization to an institution, we highlight the following individuals: quality/ safety officer, data analyst, community members, DEI leaders, physicians, nurses, and registration personnel. Dashboard designers must also thoughtfully consider the benefits of an integrated versus a standalone product.

Integrated dashboards are akin to adding a “column” or “filter” to an existing dashboard. This approach has the shortest startup time. An integrated approach is more likely to catch the attention of key stakeholders such as quality and patient safety officers. It is also reliant on the agreement of those managing these dashboards that the inclusion of this type of stratification is both important and worthy of report, particularly if a health care disparity is identified. Adding complexity to a dashboard can undermine the intent to provide simplified digestible information.

Administrators may find it distracting to have multiple aims for a given dashboard (e.g., highlighting disparities, evaluating individual performance metrics, and meeting operational/capacity demands). This may represent a significant initial barrier to successful implementation.

On the other hand, homegrown versions of dashboards to address department-specific issues have the benefit of truly building in an equity lens from the ground up. This requires a greater initial investment but can be tailored to the needs and health care disparities experienced in a particular community and may include numerous populations. Routine data collection by existing dashboards may not capture these metrics. For example, an ED may decide to focus on disparities in restraint use or hallway bed utilization by varying demographics. For those with the capacity to prioritize ED-specific dashboards, the homegrown equity dashboard may be the way to identify setting-specific health care disparities and interventions to address them.

Regardless of the approach chosen, there will remain challenges in implementing disparities measurement in the ED. Numerous populations are affected by disparities in care and many of them are not identified by traditional demographic collection practices at time of registration. Many institutions have not yet implemented the infrastructure and personnel training to allow for the gold standard of patient self-reporting on a variety of demographic measures. Furthermore, data collection is often aligned with reporting databases such as the CMS RTI Race Code, which has few options and would benefit from additional disaggregation. For example, the current five options (and other/unknown) do not include North African and Middle Eastern descent, nor do they provide necessary granularity to identify disparities that are only experienced by a subgroup. However, this limitation only amplifies the need to pursue change to provide equitable care when even small disparities are noted.

Evaluation of existing data collection and quality efforts to detect and impact disparities in care for minoritized racial and ethnic groups as well as women, immigrants, the elderly, those with cognitive or physical disabilities, children, those living in rural areas, and LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer) populations is where we must begin our endeavor to truly provide equitable care. While this list may not even be all-encompassing, its length highlights the amount of work ahead of us to provide equitable care

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Norman is an associate professor and serves as the associate chair of health equity, quality and safety in the Department of Emergency Medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center. She currently serves as chair of the SAEM Equity and Inclusion Committee and is a past president of SAEM’s Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine.

Dr. Hammond is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center where she also serves as the assistant medical director for the Adult Emergency Department.

Dr. Hunt, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine, serves as medical director for the Adult Emergency Department at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center.

Dr. Tsuchida is an emergency medicine physician and assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Dr. Tsuchida leads the DEI committee for the BerbeeWalsh Department of Emergency Medicine and collaborates with department and institutional leaders in embedding health equity into clinical practice. @rtsuchida

“The greatest argument for an health equity dashboard centers on the principle that problem identification and planned interventions require the availability of data to describe gaps, set aims, and allow for continued evaluation of interventions.”

The Impact of COVID-19 on Communication in the Health Care Setting for People With Disabilities

By Jason M. Rotoli, MD, Cullen Donelly, MD, and Richard Sapp, MD, MS, on behalf of the SAEM Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency MedicineA critical feature of modern, evidencebased medicine is the importance of establishing a therapeutic alliance, including clear bidirectional communication, between the practitioner and the individual. With proper communication, a therapeutic alliance can be built allowing for shared decision-making; however, this requires both the patient and practitioner to understand each other’s verbal communication, nonverbal language (body language, tone, facial expressions) and cultural nuances. Communication, however, is not without its barriers for many individuals within the disability community (~26% of the US population), which can affect an individual’s health and access to health care. In 2018, Stransky et al. found that individuals with disabilities affecting

communication reported higher rates of “trouble finding a provider” for health care. Additionally, the same group of individuals were found to have higher rates of emergency department (ED) use, longer in-patient hospital stays, and more unmet care needs.

Impact of COVID-19 on Communication in the Disability Community

Communication in the health care system was stifled in the disability community in many ways during the COVID-19 pandemic. Information regarding the pandemic has been delayed, incomplete, or inaccessible to those with hearing loss or low vision. A study also found that there were limited exceptions for visitation policies allowing individuals with disabilities to have a

member of their support team present, who is often critical to communication. Among all study sites, only 39% of hospitals reported exceptions for persons with cognitive impairment and 33% had exceptions for persons with physical impairment. Sites with EDspecific policies reported even fewer exceptions for patients with cognitive impairment (29%) or with physical impairments (24%).

With the advent of mask use during COVID-19, difficulties surrounding communication in the emergency department and health care system have been exacerbated. Individuals who rely on visual language, facial expression, and/or lip reading to aid in comprehension have lost that ability with the use of masks. While some patients

have access to masks with clear shields/ windows allowing for parts of the face and mouth to be seen while speaking, these may not be widely available and may still be less than ideal (e.g., fogging up, incorrect mask size/fit, poor visibility/ quality).

Due to COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 hospital and ED overcrowding, patients are often boarding in alternative treatment areas (such as hallway chairs/beds), on hospital floors, and in EDs. In these areas, there is increased background noise, a lack of privacy, and overall increased distractions that perpetuate suboptimal communication between patients and their providers. Moreland et al. studied health care changes in the face of COVID-19 and reported that hospitals now face challenging communicative environments due to noisy equipment alarms, hurried health care teams spending less time with patients, and personal protective equipment (PPE) use that obstructs faces and muffles sounds. Additionally, these alternate treatment areas can be challenging to navigate for people with low vision or blindness and people who use a wheelchair for mobility.

The result of these communication barriers is still being investigated; however, people in impoverished socioeconomic classes and who have more chronic health conditions tend to have more severe disease and death in the setting of the pandemic. Although speculative, logic would suggest the disease burden and death toll to be higher in the disability community.

Tips for Improved Communication and Care

While 26% of Americans have disabilities, it was found that only 4.6%% of medical students disclose disabilities or request accommodations and current physicians with disabilities only represent only 3.1% of the workforce. Similar to other racial and ethnic minority groups, people with disabilities are more likely to be able to communicate with, relate to, and provide comfort to those with whom they can identify. This is a strong argument for further diversifying our health care workforce to include people with disabilities.

The most meaningful and impactful learning experiences in medicine come from learning from patients’ first-hand experiences and the impact it has on their lives; yet, in 2017 only 52% of

medical schools reported having disability awareness training programs. Of those schools, only 10% had individuals with disabilities involved in the training program creation. Recent research shows that when medical students do receive training on disability, especially when this training is informed by individuals with disabilities, they report greater awareness of issues affecting individuals with disabilities and are able to understand disability through both biomedical and social models. For example, at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, a yearly experience called “Deaf Strong Hospital” is held where medical students participate in a role-reversal exercise during which they are hearing patients in a hospital where all the providers are deaf American Sign Language (ASL) users. In this situation, the students are encouraged to use different modes of communication (gesturing and other visual communication tools) and receive a first-hand view of health care through the lens of deaf individuals. In order to improve education on care of those with disabilities, undergraduate medical education should include more experiential activities related to care for the disability community. These experiences enhance development of alternative modes of communication, improve cultural awareness, and allow development of empathy and improved patient-provider rapport.

Additionally, medical school graduation requirements may also be modified to be more inclusive and meet the educational needs of the learner (with or without a disability). For example, modifying required competencies for the obstetrics clerkship (from completing the delivery of a baby to assisting in a delivery) may provide the necessary education if the student does not intend to pursue obstetrics. Another example is the requirement to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The ability to perform CPR is often a barrier for applicants with disabilities; however, some programs’ requirements now state that applicants must be able to direct or perform CPR, which is more inclusive, provides the same education, and may better meet the needs of the student, thus changing these technical standards. These small adjustments to competencies allow students with physical disabilities (including those with chronic illnesses), who may otherwise be deemed

“unqualified,” to meet the requirements of their program and increase the disability community presence within physician workforce leading to the aforementioned benefits.

Flexible communication strategies including visual communication (body language, gesturing, writing/ text when feasible, qualified ASL interpreters) and communication technology (tablets, communication boards, communication access realtime translation [CART], etc.) can also increase the information exchange during a patient encounter. Additionally, flexible institutional policies allowing health care/support team members to accompany a patient with a disability during their visit may also enhance communication, information exchange, and access to more equitable care.

Conclusion

With existing communication barriers for patients with disabilities, conveying accurate and accessible health care and health information is a critical responsibility of health care practitioners to minimize misinformation and improve outcomes. While the health care system continues to deal with overcrowding and a thinly stretched workforce, steps must be taken to provide care for individuals with disabilities in the pursuit of positive health outcomes and improved access to their providers.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Rotoli is associate residency director, Department of Emergency Medicine and director, Deaf Health Pathways, at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

Dr. Donelly is an emergency medicine resident at the University of Rochester '25

Dr. Sapp is a second-year resident in the Harvard Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency (MGH/BWH) who is passionate about improving health care for individuals with disabilities.

@SappMD

Reflections from the Twilight Zone: Navigating Medicine as a Nonbinary Medical Student

By Mel Ebeling on behalf of the SAEM Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine

By Mel Ebeling on behalf of the SAEM Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine

Less than 1% That’s how many medical students and physicians there are in the U.S. who identify as transgender or nonbinary. What does it look like to be part of that percentage? Right now, for me, it looks like waddling through medical school with T-rex arms, plaid button-ups in the anatomy lab, pausing studying to milk my JP drains, and perhaps most exhaustingly, one too many explanations. “What’s ‘top surgery’?” “Why are you getting it?” “Do you identify as a man now?”

Before beginning this process of transitioning into the right body, the “issue” of my gender identity seemed to reside in my use of they/them pronouns. Who knew the pronoun pin on my white coat could be so controversial… and

so terribly ineffective? Despite their best intentions, I soon began to feel the strain of being misgendered by peers, patients, and preceptors day after day. The pin, measuring just one inch in diameter and weighing only nine grams, quickly began to feel heavier and heavier with each disregard. I gave up on correcting.

Unfortunately, my experience as a nonbinary person — and a nonbinary person in medicine, nonetheless — is not an uncommon one. Misgendering of transgender and gender-expansive physicians in professional settings is reportedly quite common. In the general public, one Canadian report revealed that about 60% of its nonbinary

"about a quarter of transgender individuals avoid getting the health care they need out of the fear of mistreatment."

respondents were misgendered daily. Intentional or not, being misgendered can negatively impact one’s health and wellbeing. Outside of misgendering, another study found that most transgender and nonbinary students and physicians have heard derogatory remarks at their workplace or training program about transgender and nonbinary individuals. Seventy-five percent of this same group of participants spent much of their time at school or work intentionally changing their speech and behavior to avoid being outed. This certainly cannot be good for one’s health either. It comes as no surprise, then, that about a quarter of transgender individuals avoid getting the health care they need out of the fear of mistreatment.

What can we do about this? As with many things, education is always a good place to start. The good news is that physician training in LGBTQ+ health has been increasing over the past decade. Specifically, emergency medicine residency programs have demonstrated a 26% increase in training from 2013 to 2020; however, the amount of training provided does not meet desire, and too many emergency medicine residents feel challenged when performing a history and physical examination on a patient who identifies as LGBT. In light of 40% of transgender individuals attempting suicide, a situation that emergency medicine physicians will likely be tasked with helping mitigate, more action and more education are necessary to promote better care for our transgender/

About ADIEM

nonbinary patients and treatment of our transgender/nonbinary colleagues.

Luckily, there are several ways education on LGBTQ+ health can be implemented across the spectrum of physician training. For example, if you are an attending physician wanting to increase your own knowledge on LGBTQ+ health, this could mean doing some continuing education on the topic. If you direct a residency program, this could mean using simulation to enhance your residents’ cultural competence.

If you have a title that grants you the power to revamp undergraduate medical education, maybe this means incorporating a presentation on the Genderbread Person into the curriculum.

As I sit here, recovering from genderaffirming surgery and writing this article, I wonder what it will take for us, the 1%,

to be included in the AAMC’s definition of “Underrepresented in Medicine”? What will it take for our own health care needs to be better met? What will it take for us to be respected more in the training environment and workplace? Frankly, I am unsure of what it will ultimately take, but it will most certainly take more than a pronoun pin.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Mel Ebeling (they/them/theirs) is second year medical student at The University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine and a practicing emergency medical technician/ hazmat specialist in the fire service mebeling@uab.edu

The Academy for Diversity & Inclusion in Emergency Medicine (ADIEM) works towards the goal of diversifying the physician workforce at all levels, eliminating disparities in health care and outcomes, and insuring that all emergency physicians are delivering culturally competent care. Membership in SAEM's academies and interest groups is free. To participate in one more groups: 1.) log into SAEM.org; 2.) click “My Participation” in the upper navigation bar; and 3) click “Update (+/-) Academies or Interest Groups.”

"In light of 40% of transgender individuals attempting suicide, a situation that emergency medicine physicians will likely be tasked with helping mitigate, more action and more education are necessary to promote better care for our transgender/nonbinary patients and treatment of our transgender/nonbinary colleagues.

Hackschooling Residency Education

By Nadeem El-Kouri, MD, and Brian Milman, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Education CommitteeThe Current System

Current graduate medical education usually revolves around a didactic framework designed as a one size fits all model in which learners are expected to conform to the pace and educational level of the rest of the cohort.

Classically, residents attend a weekly conference that minimally considers their existing knowledge and proficiency on the subject. For the average learner, this approach is not a significant issue as the system is catered to the average. The above average learner is often not challenged by formal curricula. They are left to find opportunities to challenge themselves as the system functionally neglects them; unfortunately, limited free time outside of residency makes this difficult to accomplish. In contrast,

the below average learner will likely be overwhelmed with the proficiency gap and the disparate performance of their peers. Depending on the magnitude of their deficit they may start residency with few true opportunities to progress, further solidifying their limitations.

As medical schools and residency programs increasingly consider moving towards curriculums based on entrustable professional activities (commonly referred to as EPAs) it is important for residency programs to

consider a similar, more customizable educational framework. This strategy engages students at their specific spot in the journey of proficiency regardless of where they fall on the spectrum. This approach allows for more focus on the individual learner’s proficiency and goals.

What is Hackschooling?

Originally coined by the homeschooling family of the then 13-year-old Logan LaPlante at his TEDx talk in February 2013, the term was used to refer to

“Hackschooling allows residents who excel to continue to grow regardless of their skill. ”

hacking one’s own education. Though many may have a negative impression of hacking, at its core, it confers a sense of creativity and going outside the established norm to find answers to problems. Even in the most negative light, a hacker must have an extensive understanding of their subject. This in-depth comprehension begets the creativity that makes life-hacking so appealing. It does raise the question, “why can't this be applied towards the medical education model?”

Medicine

The medical profession prides itself on a culture of lifelong learning which requires us to take charge of our own education post residency. This is no longer just the mark of a good physician, it has become a requirement to stay relevant and practice safe medicine in the era of an ever evolving practice landscape. This necessitates high degrees of curiosity, self-awareness, motivation, and drive. It is not feasible to expect people to spontaneously demonstrate these qualities upon graduating residency after being spoon-fed high yield/necessary information for all of residency (and arguably medical school). Just as in sports, you should practice how you intend to play. These are characteristics which are honed through repetition.

A Logical Application

Lifelong learning requires self-awareness to identify knowledge deficits followed by identification of ways to fill gaps. When learners are exposed to a regimented curriculum throughout residency, adjusting to post-residency learning is difficult. Our goal should be to help train the habits which make successful physicians. Self-directed learning is a crucial aspect of that. A hackschooling

approach offers learners more control over their own education allowing them to direct their focus to what they need most.

Such a curriculum also allows people to explore interests within the specialty. Many residency curriculums do not have flexibility to allow subspecialization or exploration of possible fellowship interests due to staffing needs within a department, commitments to off service rotations, etc. A customized and interactive educational journey afforded by hackschooling allows learners to go deeper into topics that they may otherwise have had minimal exposure to in the current framework. This approach also has the potential to engage learners as they are being stimulated and pushed in ways that are meaningful for them.

The pre-residency experience is so unique for each resident that their educational and experiential foundation cannot be assumed to be the same from resident to resident. This is the assumption with a predefined residency curriculum, and it is a faulty one. Even the examples above regarding the average learner is an oversimplification. There are so many subdomains that demand proficiency to be a competent physician. The average learner is almost never truly average in each subdomain. Each person is heterogenous amalgam of these subdomains.

It is more efficient and interactive to provide an educational framework that adapts to the learners needs, meeting them where they are and engaging their interests. Despite attempts within the first few months of residency to homogenize learners’ competency their unique pre-residency experiences ultimately make this challenging, inefficient, and increasingly impractical. Hackschooling allows residents who excel to continue to grow regardless of their skill. Instead of a standardized model where students may be throttled and other students may be pushed to aggressively, facilitating burnout, such a customized curriculum allows all learners to grow simultaneously.

Progress