Breaking Barriers, Building Pathways

A Conversation With 2025–2026 RAMS President

Daniel Artiga, MD

A Conversation With 2025–2026 RAMS President

Daniel Artiga, MD

Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS

SAEM President

Emory University School of Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Bylaws Committee

• Governance Committee

• Ethics Committee

Jody A. Vogel, MD, MSc, MSW

SAEM President-Elect

Stanford University

Board Liaison to:

• RAMS Board

• Committee of Academy Leaders

• SAEM Federal Funding Committee

• Nominating Committee

• Sex and Gender in Emergency Medicine Interest Group

Pooja Agrawal, MD, MPH

Member at Large Yale Department of Emergency Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine

• ED Administration and Clinical Operations Committee

• Grants Committee

• Behavioral and Psychological Interest Group

• Pediatric Emergency Medicine Interest Group

Bryn Mumma, MD, MAS

Member at Large

University of California, Davis

Board Liaison to:

• Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine

• Research Committee

• Disaster Medicine Interest Group

• Palliative Medicine Interest Group

• Research Directors Interest Group

• Trauma Interest Group

Cassandra Bradby, MD Member at Large East Carolina University

Board Liaison to:

• Academy of Emergency Ultrasound

• Awards Committee

• Critical Care Interest Group

• Oncologic Emergencies Interest Group

• Toxicology/Addiction Medicine Interest Group

Jane H. Brice, MD, MPH Chair Member University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Faculty Development Committee

• Vice Chairs Interest Group

Ava E. Pierce, MD

SAEM Secretary-Treasurer

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Board Liaison to:

• Global Emergency Medicine Academy

• Finance Committee

• Program Committee

• Clinical Researchers United Exchange Interest Group

• Wilderness Medicine Interest Group

Jeffrey P. Druck, MD

Member at Large

The University of Utah

Board Liaison to:

• Academy for Diversity & Inclusion in Emergency Medicine

• Fellowship Approval Committee

• Climate Change and Health Interest Group

• Evidence-Based Healthcare & Implementation Interest Group

• Tactical and Law Enforcement Interest Group

Patricia Hernandez, MD Resident Member

Massachusetts General Hospital

Board Liaison to:

• Wellness Committee

• Innovation Interest Group

• Neurologic Emergency Medicine Interest Group,

• Telehealth Interest Group

Ryan LaFollette, MD Member at Large University of Cincinnati

Board Liaison to:

• Simulation Academy

• Education Committee

• Airway Interest Group

• Operations Interest Group

• Transmissible Infectious Diseases Interest Group

Ali S. Raja, MD, DBA, MPH

SAEM Immediate Past President

Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School

Board Liaison to:

• Academy of Administrators in Academic Emergency Medicine

• Workforce Committee

• Educational Research Interest Group

• Informatics, Data Science, and Artificial Intelligence Interest Group

• Quality and Patient Safety Interest Group

Nicholas M. Mohr, MD, MS Member at Large University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Academy of Emergency Medicine Pharmacists

• Academy of Geriatric Emergency Medicine

• SAEM Federal Funding Committee

• Membership Committee

• Emergency Medical Services Interest Group

Megan Schagrin, MBA, CAE, CFRE

SAEM Chief Executive Officer

Liaison to:

• SAEM Executive Committee

• Association of Academic Chairs of Emergency Medicine (AACEM)

• RAMS Board

• SAEM Foundation

Physicians Can Help End Gun Violence Against Children

Motivation: Applying Self-Determination Theory to Enhance Well-Being in Emergency Medicine

Process, Proceed: Emotional Reflection Inside and Outside the Hospital

Repellents in Wilderness Medicine: Essential Tools for Outdoor Health Management — Part 2

and Sustaining Donors of

Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS Emory University 2025-2026 President, SAEM

It was truly a pleasure to see so many of you at SAEM25. This year’s gathering in Philadelphia was nothing short of extraordinary—a record-breaking event that reflected the incredible momentum of our community. We welcomed the largest number of attendees in SAEM’s history, and members submitted an unprecedented number of didactic sessions and scientific abstracts. The energy, engagement, and scholarly excellence on display were inspiring. Heartfelt thanks to our dedicated members and the exceptional SAEM staff for making SAEM25 our most successful annual meeting to date.

Moments like these remind us that our greatest achievements are built together. As we carry this energy forward, I plan to use this year to reflect on the strength of our SAEM community. I will be highlighting key initiatives and accomplishments to keep all members informed of our organization’s trajectory—both for the year ahead and for the future. Together, we will continue to grow stronger, more connected, and more impactful.

At SAEM, we believe that progress is driven by community—by collaboration, connection, and shared purpose. Our mission to advance academic emergency medicine through education, research, and professional development is made possible by the passion and dedication of our diverse membership. I am continually inspired by your contributions.

My own SAEM journey began as a junior faculty member when I was invited to attend a meeting of the Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine (AWAEM). I found more than a professional group—I found a home. AWAEM became a space for mentorship, growth, and empowerment. It reminded me that when we feel seen and supported, we are more likely to step forward, take risks, and lead with purpose.

I am proud to share several initiatives that reflect our continued commitment to fostering a meaningful community:

• Federal Funding Committee: This new committee will strengthen SAEM’s engagement with federal

“This year’s gathering in Philadelphia was nothing short of extraordinary—a record-breaking event that reflected the incredible momentum of our community.”

“SAEM has surpassed 10,000 members—a historic milestone that speaks to the strength, inclusivity, and vibrancy of our community.”

agencies, expand funding opportunities, and keep members informed on research priorities. Many thanks to Dr. Manish Shah for serving as its inaugural chair.

• Editor-in-Chief Search for Academic Emergency Medicine: Applications open Sept. 1 for our next editor-in-chief. We are deeply grateful to Dr. Jeff Kline for nearly a decade of outstanding leadership and look forward to building on his legacy.

• Launch of the Academy for Emergency Medicine Pharmacists (AEMP): AEMP is now SAEM’s ninth academy—an important step forward in fostering interdisciplinary collaboration. Congratulations to the founding team for this achievement.

Finally, SAEM has surpassed 10,000 members—a historic milestone that speaks to the strength, inclusivity, and vibrancy of our community. If you have not yet discovered your SAEM story, know there is a place here for you. Volunteer, connect, and be part of something bigger. Together, we are shaping the future of academic emergency medicine—and we are just getting started.

ABOUT DR. LALL: Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS, FACEP, is professor and vice chair of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine.

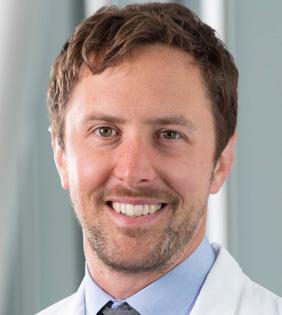

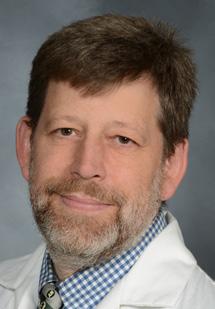

Daniel Jose Artiga, MD is a fourth-year emergency medicine resident at the University of Cincinnati and the 2025-2026 president of SAEM RAMS (Residents and Medical Students). As a first-generation Latino—and the first in his family born in the U.S., to earn a college degree, and to become a physician—he is committed to expanding access to emergency care and advancing equity, and inclusion in medicine.

Dr. Artiga earned his medical degree as a David Geffen Medical Scholar at the University of California, Los Angeles, and holds a bachelor’s degree in Molecular and Cellular Biology from Harvard University. His passion for emergency medicine was sparked by early life experiences receiving care in the emergency department, inspiring his dedication to serving resource-limited communities.

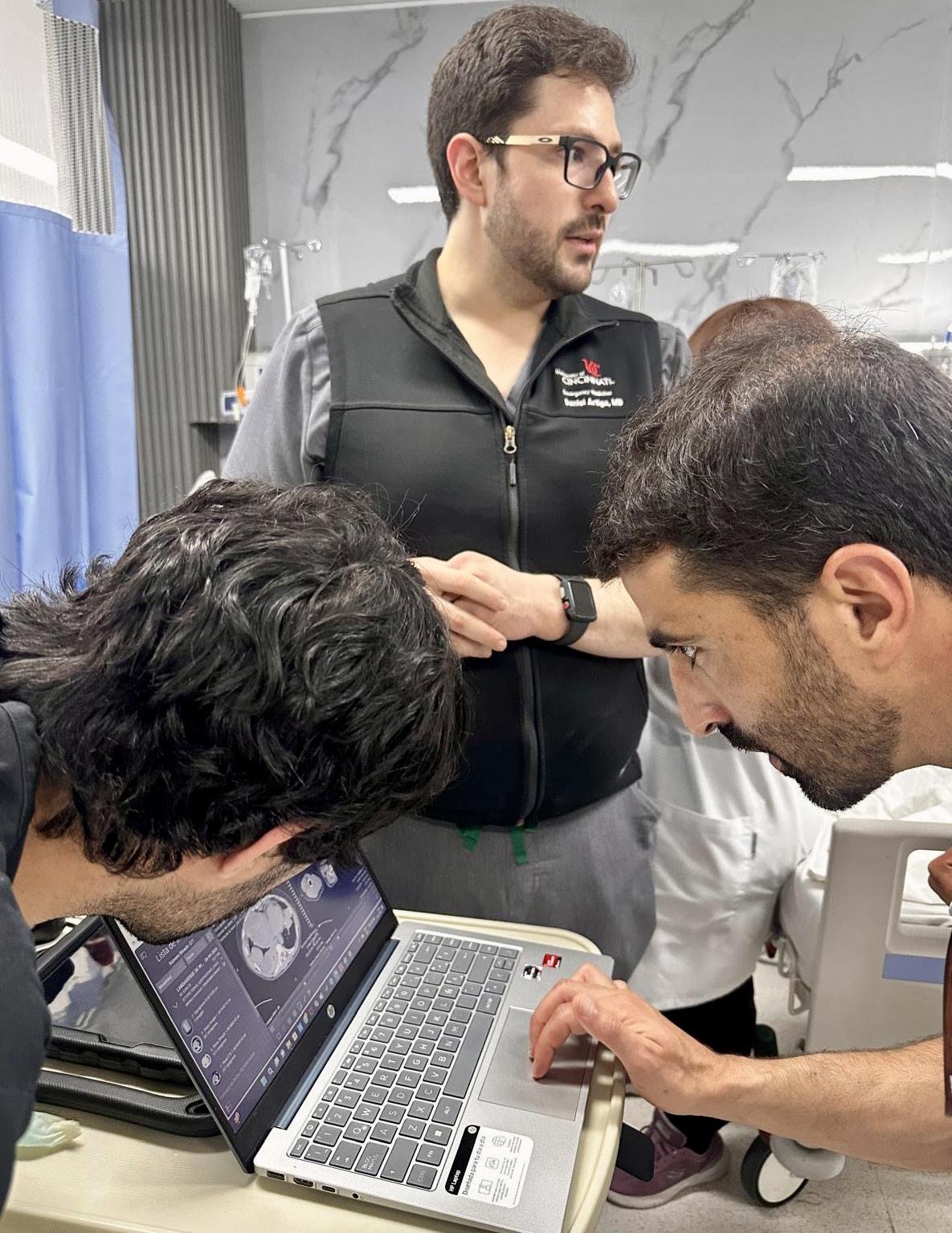

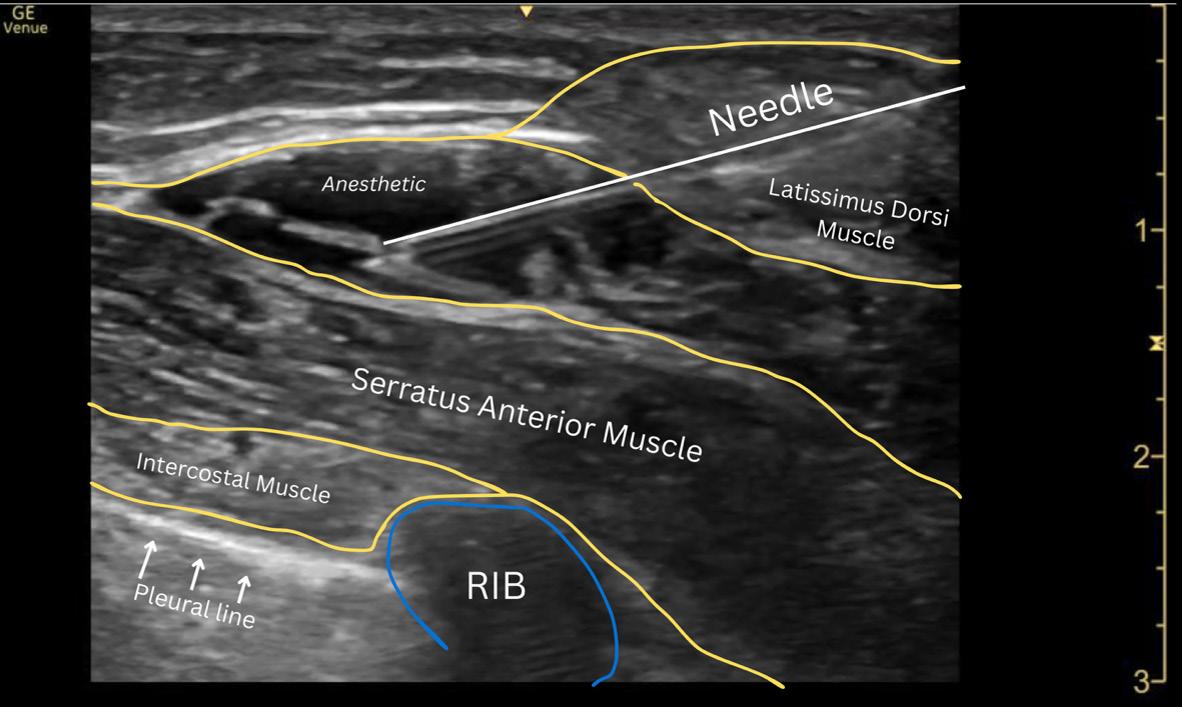

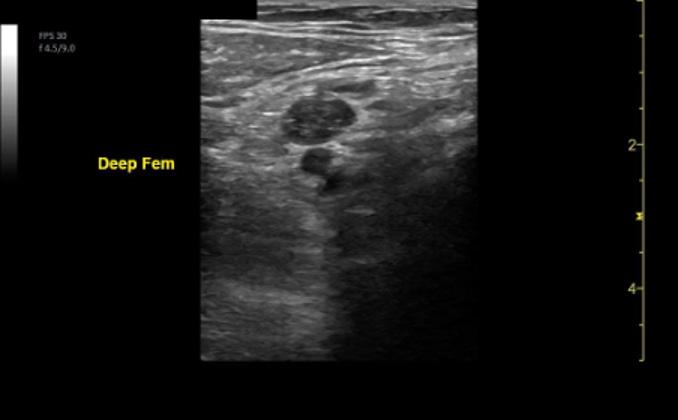

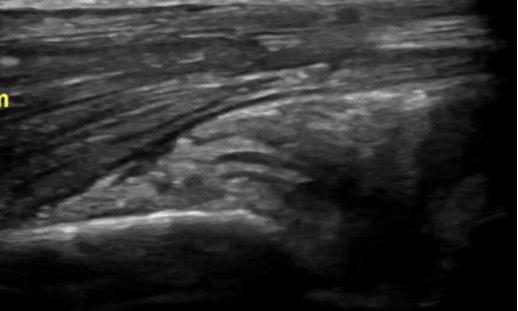

Dr. Artiga’s academic interests include ultrasound, education, and advocacy. Within SAEM RAMS, he has led initiatives such as the Ask-A-Chair educational podcast series, advocacy efforts related to unionization, social media campaigns to promote resident engagement, and the development of board review resources for emergency medicine certification. He has recently taught ultrasound to emergency medicine programs in Latin America.

Dr. Artiga plans to pursue a fellowship in ultrasound and continues to champion equitable access to care and opportunities for those underrepresented in medicine.

Your journey from receiving much of your childhood healthcare in the emergency department to leading SAEM RAMS is remarkable. How have those early experiences shaped your vision for the role emergency medicine should play—particularly in resource-limited communities— and how will that vision guide your priorities as RAMS president?

Emergency medicine (EM) was a natural fit for me because it is the only specialty that inherently serves everyone anywhere. Growing up, I experienced firsthand how the emergency department (ED) serves as a healthcare access point for those in resource-limited communities. EM directly addressed the challenges I saw around me. As RAMS president, my priorities are shaped by that foundation, even if indirectly.

While much of my current focus is on evolving issues, such as changes to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements, American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) certification, and the ResidencyCAS rollout, my broader vision ties back to equity and building pathways for underrepresented groups in medicine. Mentorship is a key part of that vision, which is how I plan to create lasting change. We're trying to expand mentorship opportunities for students and residents who may not otherwise see a path into this field. For example, we're developing initiatives and pipeline programming with SAEM’s medical student ambassadors and the Medical Student Symposium—which reflect the same kind of outreach programs that exposed me to medicine in the first place.

As a first-generation, U.S.-born Latino and a strong advocate for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), what steps do you believe RAMS and the broader academic EM community should take to empower those underrepresented in medicine? What role can RAMS play in advancing that mission?

It starts with mentorship that leads to meaningful recruitment, inclusion, and ultimately representation. We need to build pathways that don't just invite underrepresented students into the field but support them through it. We also need to be intentional about our research and advocacy. We should be studying disparities in care and ensuring we’re not applying one-size-fits-all solutions to our patients. There's a dual responsibility: caring for patients from underserved communities while also lifting up members of those communities to become providers themselves.

That’s where RAMS can play a unique role: through pipeline programs, educational initiatives, and pushing forward strategies even as the national conversation around DEI evolves. The RAMS Board plans to increase awareness of resources and opportunities available to medical students and residents through SAEM groups such as the Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine (ADIEM), the Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine (AWAEM), and the Social EM and Population Health interest group.

continued from Page 7

You’ve already made a significant impact through your involvement with RAMS initiatives—from the Ask-AChair podcast series to advocacy for unionization and global ultrasound education. Looking ahead, what new or continuing projects are you most excited to champion during your presidency?

Emergency medicine is undergoing major transitions across the board. One of the projects I’m most excited about is continuing to support the rollout and development of the ResidencyCAS platform. This platform doesn’t just streamline the application experience; it provides real-time data that programs can use to understand how applicants are engaging with EM, which in turn helps guide recruitment strategies.

At the same time, we’re seeing changes to ACGME program requirements and the ABEM Certifying Exam. These shifts raise important questions about how we define competency and what makes a capable emergency physician. During my presidency, I want to ensure RAMS has a voice in those conversations, particularly when it comes to protecting the things that

make EM unique: our broad skill set, adaptability, and patient-centered approach.

This is a critical period for the specialty, and being involved at this moment means helping shape the foundation for future trainees. That’s a responsibility I take seriously.

Balancing clinical duties, academic interests, and leadership responsibilities is no small feat for a resident. What motivates you to stay engaged at this level, and what advice would you give to other trainees looking to make meaningful contributions to academic emergency medicine?

I first became involved in RAMS because I was concerned about the direction of emergency medicine, particularly with the growing presence of for-profit models that stretch physicians to care more patients than they can realistically manage. It felt like the heart of what makes being a doctor special—giving thoughtful and attentive care to our patients’ needs—was being threatened by business decisions.

My motivation comes from a desire to protect the core of this specialty. If you care deeply about EM, you have to be part of the solution. National leadership roles

“If you care deeply about EM, you have to be part of the solution. Once you see the impact you can have, it’s hard not to want to be part of it.”

like those with RAMS give you a chance to help shape the future of the field in a structured, impactful way.

For other trainees, I’d say: find your people. Surround yourself with others who are just as passionate and driven. The most powerful changes often come from the work of these motivated groups. I’ve found SAEM to be the perfect venue to find these people.

You’ve been involved in teaching ultrasound to emergency medicine programs in Latin America. What have you learned from that experience, and how has it influenced your approach to global health and education in EM?

It was an extremely humbling and eye-opening experience. I went to teach in my father’s country, El Salvador, where I had never visited before. I never truly understood the conditions he lived in beyond his words. All the issues that exist in the U.S. are magnified when you go to countries that don’t have similar resources. Medical decision making is limited by access to resources. It’s not about a lack of capability. I worked with incredibly brilliant doctors who just don’t have access to the same technology or infrastructure we have here. That’s why I believe in supporting ultrasound specifically in these settings. In capable hands, point-ofcare ultrasound can give a clinician life-saving information. Providing this tool and empowering physicians to use it can have a huge impact on individual patients and healthcare systems across the world.

You’ve spoken about the importance of advocating for our specialty. In today’s rapidly evolving healthcare environment, what do you see as the biggest challenges facing EM residents—and how can RAMS help address them?

The biggest challenge facing EM residents right now is the changing foundation of our training. Every step—from applying to residency, to how we’re evaluated during training, to how we’re certified after graduation—is in flux. This matters because better training leads to better patient care. If we’re serious about delivering the best possible care, we must take our training systems seriously too. RAMS and SAEM are already stepping up to meet this moment. RAMS is working with the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD) to develop social media materials and guides for ResidencyCAS for new applicants to our specialty. We are in contact with ABEM to elucidate the resource materials they have released so far and plan to publish what we learn to our members. We co-wrote and co-signed a letter to the ACGME with our comments regarding changes to our specialty

requirements. RAMS board members attended the SAM25 Consensus Conference aimed at developing a research agenda for competency-based training.

Our goal is to make sure the voices of residents and students are included in shaping these changes from the ground up.

What have been some of the most meaningful lessons you’ve learned through your leadership roles within SAEM RAMS, and how have they shaped your growth as a physician and a leader?

For me, it’s been about chasing my passion and asking, “Who’s on this ride with me?” I’ve always been drawn to ultrasound. Through SAEM’s and the Academy for Emergency Ultrasound’s (AEUS’s) ultrasound didactics and activities, I’ve noticed similar faces showing up. These spaces allow for ideas to connect and develop in ways that don’t happen when you're working alone. You can’t have synergy in isolation. You need people who challenge and inspire you to promote growth. It’s individuals working together, learning from one another, and pushing ideas forward that produce progress.

As someone who’s contributed to educational resources like board review materials and the Ask-A-Chair podcast, what do you see as the most effective ways to support fellow residents in their academic and career development?

The most effective way to support others is by not gatekeeping. It’s easy to forget how far you’ve come since applying to medical school. You have to give advice in a way that benefits someone at their level of training but also sharing what worked for you when you were in their shoes. Share resources and opportunities. Coaching and being an excellent mentor to near-peers is the key. Organizing these efforts through an organization like RAMS and SAEM, however, is able to amplify that impact— creating structured, accessible pathways for mentorship, collaboration, and professional growth on a national scale. What’s one misconception people often have about emergency medicine trainees, and how would you like to see that narrative change?

A common misconception across the board is that EM trainees “just order tests and imaging.” That couldn’t be further from the truth. The sharpest senior emergency

physicians I’ve worked with order plenty of advanced tests or imaging, but not out of habit. It’s because they’ve thought deeply about the case. They’ve considered the patient’s risk factors, demographics, history, and physical. They have combined that information with clinical decision tools and years of clinical gestalt to guide their medical plan.

Diagnostics aren’t the end-all-be-all. Trainees are educated on the specificities and negative predictive values of the diagnostic tests we use to evaluate life-threatening disease. We pair those test characteristics with clinical judgment to develop a good plan for the patient. The best EM physicians are the ones who know how to use these tests and imaging modalities effectively, without relying on them but also using them when necessary.

If you could accomplish just one thing during your term as RAMS president that would have a lasting impact, what would it be—and why?

One lasting accomplishment I desire is improving communication between the RAMS Board and our resident and medical student community members. There’s so much incredible work happening behind the scenes. I do perceive a gap where members don’t know how much we are up to and how they can get involved themselves. I want more people to know opportunities exist and that they’re

accessible. My hope is that clearer communication not only showcases what RAMS is doing but inspires more residents and students to step up and get involved. Once you see the impact you can have, it’s hard not to want to be part of it.

Why should EM residents and medical students become involved with RAMS? What needs does the group meet or concerns does it address?

RAMS is the gateway for EM residents and medical students to shape the future of emergency medicine while also building their own careers. If you care about professional development, equity, or mentorship, RAMS is where those opportunities begin.

We meet a wide range of needs—from practical support with residency applications and post-residency job prep, to broader guidance through initiatives like the RAMS Career Roadmaps. We’ve built educational content across formats: webinars, podcasts, and toolkits on everything from contract negotiation to wellness. RAMS also leads on issues that matter deeply to trainees: improving ED learning environments, fostering DEI through partnerships with ADIEM and others, and pushing for resident wellbeing through campaigns like “Stop the Stigma.” And of course, we're also involved in national discussions with organizations such as ABEM, EMRA, CORD and ACGME.

Getting involved in RAMS means joining a community of peers who want to lead, teach, and transform the specialty.

If you weren’t in medicine, what career would you have pursued instead—and why? Some aspect of filmmaking. I really enjoy cinematography and being in control of the camera.

What’s one item you always have with you on shift—besides your pen and stethoscope?

Every shift, I wear a silver chain necklace my dad got me for my first communion with my wedding ring hanging from the necklace. They are reminders of my family and where I come from.

What’s the most unexpected skill you've picked up during residency?

The ability to sleep anywhere at any time. Residency is exhausting, but I also became a father at the start of residency. I now have a toddler and baby girl, and you have to sleep whenever they give you a chance.

What’s your guilty pleasure when you finally get a day off?

Giving undivided attention to my son and daughter. It’s easy to be preoccupied by the many issues affecting our country, our specialty, and our personal lives. I make a conscious effor t to ground myself with them and give them my focus and love whenever I have the chance.

If you could instantly master one non-medical skill or hobby, what would it be? Calisthenics. Have you ever seen someone do the “human flag?” It requires so much strength and body coordination.

The 2025 SAEM Annual Meeting, held May 13–16 in the heart of Philadelphia, was nothing short of legendary. With record-breaking attendance, the highest number of workshop, didactic, and abstract submissions in our history, and an electrifying atmosphere of collaboration and discovery, SAEM25 was a defining moment for academic emergency medicine

For four unforgettable days, our community came together to learn, lead, and celebrate everything that makes emergency medicine one of the most dynamic and essential specialties in healthcare. From sunrise sessions to evening strolls through Philly’s historic streets, SAEM25 was filled with powerful presentations, game-changing research, meaningful connections, and the unmistakable feeling of coming home.

SAEM25 raised the bar with a program packed full of hands-on workshops, thought-provoking didactics, and trailblazing research designed to elevate every attendee — from students to seasoned leaders. With something for everyone, the meeting featured:

• Deep-dive sessions in cutting-edge clinical and educational topics

• Innovative simulations and skill-building workshops

• Passion-fueled discussions led by top experts in the field

• Friendly, high-energy competitions to test knowledge and spark new ideas

Attendees left feeling energized, equipped, and inspired to take on the next chapter of their careers with renewed purpose.

At its core, SAEM25 was about connection. Whether catching up with old friends, forging new collaborations, or engaging in rich mentorship conversations, the meeting was a powerful reminder of the strength of our academic emergency medicine family.

SAEM25 provided welcoming spaces for networking, peer exchange, and reflection — proving once again that the relationships we build extend far beyond the walls of a conference center.

Dr. Peter Rosen Memorial Keynote: Charles Cairns, MD

Dr. Charles Cairns delivered a brilliant and visionary address, “Advancing Precision Emergency Medicine: Innovations in Translational Medicine and Population Health,” challenging us to reimagine emergency care through the lens of systems biology, big data, and the digital revolution. His insights into population health and translational research set a powerful tone for the week ahead.

With her keynote, “The Health Humanities: The Next Great Frontier in Emergency Medicine Education,” Dr. Kamna Balhara brought humanity to the forefront of emergency medicine. Her exploration of arts and humanities in

medical education was both moving and enlightening, underscoring how creativity and empathy can transform the way we learn, teach, and care.

The brightest minds in emergency medicine took center stage in our Plenary Sessions, presenting the top eight abstracts chosen from over 1,426 submissions. These sessions spotlighted bold ideas and groundbreaking research that will shape the future of our field:

• Treatment strategies for opioid use disorder

• Proteomic biomarkers in pulmonary embolism

• Resuscitation science and clinical decision-making

• Health systems innovation and education reform

These presentations, and others like them, were a testament to the rigor, creativity, and scientific excellence that defines our SAEM community.

At the opening ceremony, we proudly welcomed Michelle Lall, MD, MPH as the new SAEM President. A trailblazer in diversity, equity, and inclusion, Dr. Lall announced exciting new initiatives:

• Formation of the SAEM Federal Funding Committee to expand support for EM research

• Launch of the Academy of Emergency Medicine Pharmacists (AEMP) — our ninth academy!

• A national search for the next Editor-in-Chief of Academic Emergency Medicine

With Dr. Lall at the helm, the future of SAEM has never looked brighter.

continued on Page 14

• A heartfelt tribute honored the late Dr. Amy Kaji, SAEM Past President, with the 2025 Organizational Advancement Award. Her legacy will live on through the Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD Early Investigator Awards, supporting the next generation of EM scholars.

• In a stunning gesture of support, AACEM gifted $500,000 to the SAEM Foundation, a bold investment in the future of academic emergency medicine. The gift reflects an unwavering commitment to education, research, and innovation at the highest level.

From morning education session to evening adventures, from the halls of the conference center to the cobblestone streets of Philadelphia — SAEM25 was a celebration of everything we are and everything we are becoming. It was a place to learn, to lead, to connect, and to belong.

We are grateful to each of you who joined us and contributed to this unforgettable experience. Your passion, knowledge, and energy made history. And together, we’ll keep writing the future of academic emergency medicine.

See you next year at SAEM26 in Atlanta, Georgia — where the story continues!

Claim Your SAEM25 CME

The deadline is July 31 to claim your SAEM25 continuing medical education (CME). Just follow the steps found on this webpage

Access SAEM25 Content on SOAR

Unable to attend SAEM25 in Philadelphia or missed out on some sessions at the annual meeting? Starting in August, you'll have access to all the presentations from the annual meeting anytime, anywhere through our SAEM Online Academic Resources (SOAR) webpage. Enjoy convenient online and mobile viewing of SAEM25's Advanced EM Workshops, didactics, forums, abstracts, and more!

Note: CME credits are not designated for SAEM25 content accessed through SOAR.

The SAEM Annual Meeting is the premier event for presenting original, high-quality research and educational innovations in emergency care. Mark your calendar and start preparing to submit your work as soon as submissions open!

Advanced EM Workshops

Aug. 1 – Sep. 17, 2025

Didactics

Aug. 15– Oct. 2, 2025

Year in Review for AEMP Program

Aug. 15 – Oct. 2, 2025

Keynote

Sep. 4 – Nov. 6, 2025

Abstracts

Nov. 3, 2025 – Jan. 5, 2026

Innovations

Nov. 3, 2025 – Jan. 12, 2026

IGNITE!

Nov. 3, 2025 – Jan. 12, 2026

Clinical Images

Nov. 3, 2025 – Jan. 12, 2026

SAEM awards are given each year at the SAEM Annual Meeting in recognition of exceptional contributions to emergency medicine and patient care through leadership, research, education, and compassion. Congratulations to all of our 2025 award recipients!

University of Pennsylvania Department of Emergency Medicine (PennEM)

PennEM’s proactive and research-driven approach to wellness has positioned the department as a national leader in promoting wellness, mitigating burnout, and fostering an inclusive, supportive culture.

Vik Bebarta, MD

University of Colorado

Presented to a member of SAEM who has made outstanding contributions to emergency medicine through the creation and sharing of new knowledge.

Alister Martin, MD, MPP

Massachusetts General Hospital

Honors an SAEM member who has made exceptional contributions to emergency medicine through advancing diversity and inclusion in emergency medicine.

Arnold P. Gold Foundation Humanism in Medicine Award

Theresa Hsiang-Ting Cheng, MD, JD

University of California, San Francisco Department of Emergency Medicine

- Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital

Given to a practicing emergency medicine physician who exemplifies compassionate, patient-centered care.

Ian B. K. Martin, MD, MBA

Medical College of Wisconsin

Honors an SAEM member who has made exceptional contributions to emergency medicine through leadership - locally, regionally, nationally or internationally, with priority given to those with demonstrated leadership within SAEM.

Luan Lawson, MD, MAEd

Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine

Awarded to a member of SAEM who has made outstanding contributions to emergency medicine through the teaching of others and the improvement of pedagogy.

Judy Linden, MD

Boston University Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine, Boston Medical Center

Recognizes an SAEM member who has made significant contributions to the advancement of women in academic emergency medicine.

Nicholas Jouriles, MD

Northeast Ohio Emergency Medicine; US Acute Care Solutions; Summa Health System

Honors an SAEM member who has mentored the career advancement of other SAEM members.

Megan L. Ranney, MD, MPH

Yale School of Public Health and Yale School of Medicine

Junaid A. Razzak, MBBS, PhD

Weill Cornell Medicine

Honors an SAEM member who has made exceptional contributions to addressing public health challenges through interdisciplinary leadership in innovation – locally, regionally, nationally, internationally.

Nour Al Jalbout, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital

Mary R. C. Haas, MD, MHPE University of Michigan

Christopher E. San Miguel, MD, MEd

The Ohio State University

Honors an SAEM member, within eight years of their first faculty appointment who has made outstanding contributions to emergency medicine through the teaching of others.

Todd Florin, MD, MSCE

Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago

Tony Rosen, MD, MPH

Weill Cornell Medicine / NewYorkPresbyterian Hospital

Recognizes those SAEM members who have demonstrated commitment and achievement in research during the mid-stage of their academic career.

Ryan A. Coute, DO University of Alabama at Birmingham

Ari B. Friedman, MD, PhD University of Pennsylvania

Felipe Teran, MD, MSCE

Weill Cornell Medicine

Alex Koyfman, MD

UT Southwestern Medical Center / Parkland Health and Hospital System

Manpreet Singh, MD, MBE

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Honors an SAEM member who has made outstanding contributions to the online learning community of emergency medicine through innovative and engaging FOAMed content.

Sarah Aly, DO Yale University

Established in honor of former SAEM President Dr. Amy Kaji, this award supports early-career EM scholars committed to research by funding their attendance at the SAEM Annual Meeting to foster professional growth and development.

Priya Arumuganathan, MD University of Pennsylvania

Richmond Malabanan Castillo, MD, MA, MS Children's National Hospital

Amir J. Mansour, MD Yale University

Wendy W. Sun, MD Yale University

Presented to EM fellows in any subspecialty for outstanding dedication to education and impactful research through significant contributions, presentations, and publications.

Konnor Davis

University of California, Irvine School of Medicine

Honors a medical student or practicing emergency medicine resident taking a leading role in their student interest group or residency program and making an impact on the local, regional, national, or international level through their efforts.

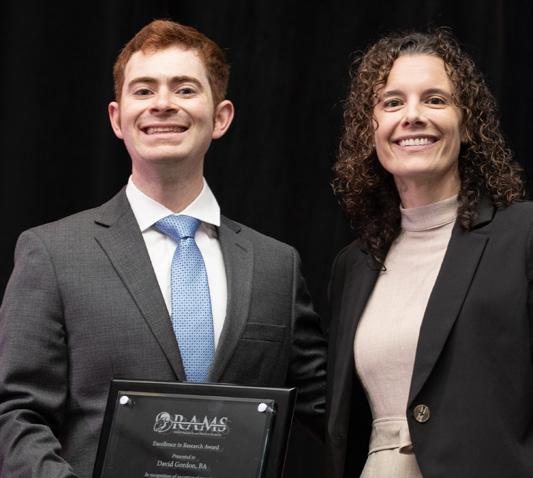

RAMS Excellence in Research Award

David Gordon

Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University

Awarded to annually to a senior emergency medicine resident or student who has demonstrated exceptional promise and early accomplishment in the creation of new knowledge.

RAMS Resident Education/Innovation Award

Patricia Hernández, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital

Given to underrepresented medical students who demonstrate a strong commitment to and leadership skills in emergency medicine.

RAMS Excellence in Education Award

Michael DiGaetano, MD

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

Given annually to a senior emergency medicine resident who has demonstrated exceptional aptitude and passion for teaching during residency.

RAMS Medical Student Education Award

Rana M. Barghout

Weill Cornell Medicine

Given to a senior medical student who has demonstrated excellence in the specialty of emergency medicine.

SAEM Annual Meeting | May 18–21, 2026 Atlanta Marriott Marquis

Get ready for a next-level annual meeting experience in the heart of Atlanta, Georgia! Here’s what’s in store at the stunning Atlanta Marriott Marquis:

• Spacious, modern meeting rooms for seamless learning and networking

• Expansive common areas perfect for casual conversations and impromptu meetups

• Friendly, expert hotel staff who know how to support large-scale events

• On-site Starbucks—mobile orders ready in just 6 minutes

• Tons of nearby restaurants and eateries within walking distance

• Clean, welcoming city vibe with city ambassadors ready to guide you

Mark your calendars now. You won’t want to miss it!

SONOGAMES® CHAMPIONS

UConn Emergency Medicine

DODGEBALL CHAMPIONS

UT Southwestern

SIMULATION ACADEMY SIMWARS CHAMPIONS

Massachusetts General Hospital

• American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM)

• American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP)

• ApolloMD

• ARS Pharmaceuticals Operations, Inc.

• AstraZeneca

• AstraZeneca

• B Braun Medical Inc

• Brault

• BRC

• Butterfly Network

• Ceribell

• Cleo Health

• CyrenCare, Inc.

Bingo! Tiles Sponsors

• American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP)

• ApolloMD

• Brault

• B Braun Medical Inc

• The Guthrie Clinic

• Geisinger Health System

• Natus Medical

• Purdue Pharma LP

• SERB Pharmaceuticals

• TEAMhealth

• Vituity

Childcare Area

• Brown Emergency Medicine

• Medical College of Wisconsin

• The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

• University of Cincinnati Medical Center/College of Medicine

• University of North Carolina Hospitals Chapel Hill

• Stanford University Department of Emergency Medicine

• Rush University Medical Center

• Diasorin

• EchoNous

• Emergency Care Partners

• Emergency Medicine Foundation

• Emergency Medicine Specialists

• Emergent Medical Associates

• EMrecruits

• GE Healthcare

• Geisinger Health System

• The Guthrie Clinic

• HCA Healthcare

• Liaison - ResidencyCAS

• Locum Physicians United

• Mayo Clinic & Mayo Clinic Health System

• Medical College of Wisconsin

• Medlytix

• Mindray North America

• Natus Medical

• ODBMed

• Orthoscan

• Penn State Health

• Permanente Medicine

• PGY1 Financial Solutions Corp

• Purdue Pharma LP

• QuidelOrtho

• Radiometer Medical

• Safer Medical LLC

• Sandhills Emergency Physicians

• Sayvant

• SERB Pharmaceuticals

• SonoSim, Inc.

• TEAMHealth

• U.S. Bank Private Wealth Management

• Ubuntu Med

• University of Maryland Emergency Medicine Associates

• UPMC Emergency Medicine

• US Acute Care Solutions

• Vituity

• Washington University School of Medicine

• WestJem

• Zeto, Inc.

In-Kind Commercial Supporters

• AMBU

• B Braun Medical Inc

• GE Healthcare

• Mindray North America

• Philips Point of Care Ultrasound

• Sonosim

• Sonosite

• Verathon

Luncheon with Chairs

• Emergency Medicine Residents' Association (EMRA)

Consensus Conference

• Association of Academic Chairs of Emergency Medicine (AACEM)

• CORD Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors

• Stanford University Department of Emergency Medicine

• American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM)

• Diasorin

Philadelphia Hunt

• US Acute Care Solutions

RAMS Party

• The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

• Stanford University Department of Emergency Medicine

• Medical College of Wisconsin

Residency/ Fellowship Fair

• Vituity

• TEAMhealth

• Stanford University Department of Emergency Medicine

• Gilead Sciences

• AstraZeneca

• Zeto, Inc.

• Butterfly Network

• Echonous

• GE Healthcare

• Mindray North America

• Philips Point of Care Ultrasound

• Sonosite

• Sonosim

• B Braun Medical Inc

Volunteer Event

• Providers Clinical Support System-Opioid Response Network (PCSS - ORN)

By Brian Kenny, DO, MBA, MBe; Mina Attaalla, DO; Puja Singh, MD; and Anthony Rosania, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Vice Chairs Interest Group

Ensuring optimal patient care and staff satisfaction in emergency medicine requires more than clinical expertise—it demands active, visible leadership. One effective strategy to foster this kind of leadership is daily administrative rounding. This simple yet impactful practice involves department leaders regularly visiting the emergency department to observe operations, engage with staff, and address concerns in real time.

This approach, rooted in Lean Management, is often referred to as “going to the Gemba”—a Japanese term meaning to visit the “front lines” to understand the current state of operations and address conflicts. Although frequently overlooked in favor of formal reports and metrics, daily rounding provides a wide range of tangible benefits. It also serves as a real-time sensing mechanism to ensure operational interventions are not only implemented but effective.

Daily rounding offers staff a consistent opportunity to voice concerns, share ideas, and receive real-time feedback. The visibility of leadership through rounding communicates that employees are valued and heard.

Sara Berg, writing for the American Medical Association, describes how addressing small problems—or

“Daily administrative rounding in the emergency department is a low-cost, high-impact strategy that strengthens communication, improves team and patient experiences, and supports a culture of accountability.”

“pebbles”—in real time can reduce physician burnout and increase team morale. Left unaddressed, these issues are often managed through workarounds or become part of normalized deviance, which may create resistance to change.

Administrative rounding allows leaders to identify these issues, understand them, and develop timely interventions. This visibility and responsiveness from leadership communicates that staff are valued and heard, fostering a sense of connection and support. Over time, this kind of engagement contributes

to better teamwork, improved job satisfaction, and lower turnover rates.

Rounding allows leaders to directly observe safety risks, communication breakdowns, or inefficiencies that might otherwise go unnoticed. Immediate action can then be taken to address concerns before they escalate. For example, rounding may identify recurring delays in triage or malfunctioning equipment.

Timely interventions support a culture of continuous improvement

and reduce the risk of adverse events. Without active engagement, minor problems may go unnoticed, leading to latent safety risks. Rounding also allows administrators to reinforce new processes through positive feedback and checklist validation.

Rounding improves communication between frontline staff and administration by providing a direct,

“Too often, small problems—the aforementioned ‘pebbles’—are accepted as part of the norm, introducing risk and undermining larger quality improvement efforts.”

ADMINISTRATION

continued from Page 21

unfiltered channel of information. This reduces distortion from the “telephone game” effect that often accompanies multilayered communication chains.

This transparency builds trust, accelerates problem-solving, and fosters an environment in which staff members feel empowered and involved in decision-making. When staff understand the rationale behind new initiatives and have a voice in their development, they are more likely to support and implement them.

Daily rounding enables leaders to identify and address issues immediately. This real-time troubleshooting enhances departmental agility and supports smoother operations and improved patient throughput.

Too often, small problems—the aforementioned “pebbles”—are accepted as part of the norm. Not only does this introduce risk, but it also creates an environment where larger quality improvement efforts fail due to a lack of buy-in. Engaging with staff and promptly removing these “pebbles” allows leaders to “celebrate small wins,” a critical component of building sustainable change.

Additionally, this process allows staff to observe and learn from administrators who model systemsbased practices and effective communication strategies.

Patients and families take notice when leaders are present and engaged. When administrators interact directly

with patients, it reinforces that the patient experience matters. This personal attention can improve patient satisfaction, especially when feedback leads to measurable improvements.

In one study by Borinski and colleagues, patient satisfaction scores increased by up to 20% following the implementation of regular administrative rounding. Rounding should intentionally include patients waiting in hallway beds or those admitted and awaiting inpatient placement. Despite best efforts, patients boarding in the emergency department associate their experience with the emergency team—making these interactions critical touchpoints.

Although rounding is largely observational and interpersonal, it complements data analytics by adding context to performance metrics. It can uncover the underlying causes of trends seen in reports and surface systemic issues.

Combining the qualitative insights from rounding with quantitative data creates a more complete picture for strategic planning and resource allocation. Rounding may also identify opportunities to collect data not captured by the electronic health record or other reporting tools. When planned intentionally, rounding can include mechanisms for capturing this real-time, experiential data.

Daily administrative rounding in the emergency department is a low-cost, high-impact strategy that strengthens communication, improves team and patient experiences, and supports a culture of accountability.

Consistent leadership presence reinforces expectations for high standards and ensures that policies and best practices are followed. In a complex, fast-paced environment like emergency medicine, these daily check-ins help leaders stay connected to the front lines and foster continuous improvement.

Dr. Rosania is the vice chair for clinical operations and the chief of the division of operations, quality and informatics at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. In addition to emergency medicine, he is board certified in clinical informatics and healthcare administration, leadership and management.

Dr. Singh is the fellow in healthcare operations, quality and leadership at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and an attending physician at University Hospital in Newark, New Jersey. She completed residency at Mount Sinai Morningside-West in 2024 and is currently pursuing a Master of Business Administration while completing her fellowship.

Dr. Kenny is an assistant fellowship director and assistant medical director at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. He is also an assistant professor there.

Dr. Attaalla is the emergency department medical director of quality at University Hospital, where he leads quality improvement and patient safety initiatives for the department of emergency medicine. He is also an associate professor at Rutgers University, where he teaches and mentors residents and medical students in emergency medicine, simulation medicine, point-of-care ultrasound, emergency critical care and evidencebased emergency medicine.

By Alicia Pycraft, PharmD, on behalf of the SAEM Academy of Emergency Medicine Pharmacists

Penicillin allergies are the most commonly reported drug allergies, with approximately 10% of patients worldwide claiming to be allergic. However, studies show that 95% of these individuals do not have an IgE-meditated hypersensitivity and can tolerate penicillins safely. In many cases, symptoms of viral illness—such as rash or fever—are misinterpreted as allergic reactions, leading to inaccurate labeling in childhood.

Mislabeling patients with penicillin allergies can significantly affect clinical outcomes, as beta-lactams

are often first-line therapies for many infections. Patients labeled as allergic are frequently prescribed second-line or broader-spectrum antibiotics, which contributes to antimicrobial resistance.

Documented penicillin allergies have been associated with increased risks of healthcare-associated infections, surgical site infections, prolonged hospital stays, higher antibiotic costs, and increased readmission rates

Although many patients are incorrectly labeled as allergic, penicillin remains the leading cause

of drug-induced anaphylaxis in the United States among those with true allergic reactions. Therefore, careful evaluation of reported penicillin allergies is essential to ensure safe and effective antimicrobial therapy.

When evaluating a reported penicillin allergy, it is critical to distinguish low-risk histories from true immune-mediated hypersensitivity. Low-risk histories may include gastrointestinal upset, a family history of penicillin allergy, pruritus without rash, or remote, unknown

“Approximately 95 percent of individuals who report a penicillin allergy do not have an immunoglobulin E-mediated hypersensitivity and can safely tolerate penicillins.”

reactions without IgE-mediated features. Clinical decision-making tools, such as the PEN-FAST score, can assist in identifying low-risk patients.

Clinically significant hypersensitivity reactions are immune-mediated and best understood through the Gell and Coombs classification system, which categorizes reactions into four types:

• Type I is immediate and IgEmediated. Re-exposure to the allergen leads to rapid-onset symptoms such as urticaria, bronchospasm, hypotension, and potentially life-threatening anaphylaxis. Notably, these reactions tend to diminish over time with approximately 80% of affected individuals developing tolerance within 10 years.

• Type II involves antibodymediated cytotoxicity, which can manifest as hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, or neutropenia, typically within hours to days of exposure.

• Type III is caused by immune complex formation and deposition in tissues, leading to complement activation and inflammation. These reactions generally emerge one to three weeks after exposure and may present as serum sickness–like syndromes, vasculitis, or immune complex–mediated arthritis.

• Type IV is a delayed, T-cell–mediated response that can appear days to weeks after drug administration. Reactions range from mild maculopapular eruptions to severe cutaneous

adverse reactions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. This category also includes isolated organ involvement, such as acute interstitial nephritis or drug-induced liver injury.

Accurately identifying the type of hypersensitivity reaction is crucial for diagnosis, risk assessment, and determining whether rechallenge, desensitization, or alternative antibiotics are appropriate.

A detailed allergy history is vital to classifying the reaction type and

“By conducting a thorough allergy history and applying appropriate delabeling strategies, emergency clinicians can promote antibiotic stewardship and expand access to effective beta-lactam treatment options.”

ASK THE PHARMACIST

continued from Page 25

ensuring patients receive optimal antimicrobial therapy. When assessing penicillin allergies, consider asking the following questions:

• What is the name of the medication?

• How was the medication administered?

• How long ago did the reaction occur?

• What were the signs and symptoms?

• How long after taking the medication did symptoms start?

• When in the course of therapy did the reaction occur?

• What other medications were being taken at the time?

• Why was the medication prescribed?

• What treatment was required to manage the symptoms?

• Had the patient taken this medication or a cross-reacting medication before?

• Has the patient taken the same or similar medications since the reaction?

Several strategies are available for penicillin allergy delabeling, depending on the nature and severity of the reaction. For patients with a history of anaphylaxis or a recent reaction suggestive of IgE mediation (e.g., immediate-onset urticaria), skin testing is recommended.

For adult patients with low-risk allergy histories and pediatric patients with benign cutaneous drug reactions, a direct oral amoxicillin challenge is preferred. This involves administering a full dose of amoxicillin, followed by 30 to 60 minutes of observation. If no reaction occurs, the allergy label can be removed from the medical record.

Skin testing and oral challenges are contraindicated in patients with histories suggestive of type II, III, or IV hypersensitivity.

Beta-lactam antibiotics contain a core beta-lactam ring and up to three variable side chains (R1, R2, R3). Cross-reactivity between penicillins and cephalosporins is primarily due to structural similarities in the R1 side chain. The estimated cross-reactivity rate is approximately 2% to 8% for first-generation cephalosporins and less than 1% for later generations and carbapenems.

Recent evidence shows that true immunologic cross-reactivity is much lower than previously believed. Historically, it was recommended that patients with penicillin allergies be skin tested prior to receiving cephalosporins due to cross-reactivity risk. A 2022 practice parameter update published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology supports a simplified approach:

Patients with an unverified, nonanaphylactic penicillin allergy may receive any cephalosporin without prior testing. Even patients with a documented history of IgE-mediated anaphylaxis may safely receive a noncross-reactive cephalosporin (e.g.,

cefazolin, ceftriaxone, or cefepime) without testing. Carbapenems may also be used safely in patients with prior penicillin or cephalosporin allergies, regardless of the severity of the reaction.

However, patients with a history of type II through IV hypersensitivity reactions should not be re-exposed to any beta-lactam agents without consultation with an immunologist. In these high-risk cases, alternative antimicrobials should be chosen based on the infection source and local susceptibility patterns. If no safe alternative exists, rapid desensitization may be required.

Penicillin allergies are frequently reported, but most patients do not have true immune-mediated hypersensitivity. Mislabeling leads to unnecessary use of second-line antibiotics and contributes to poorer outcomes. Emergency clinicians can improve antibiotic stewardship and patient safety by taking thorough allergy histories and applying evidence-based delabeling strategies. This enables broader use of effective beta-lactam agents and reduces the risks associated with inappropriate antibiotic selection

Dr. Pycraft is an emergency medicine clinical pharmacy specialist at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, Maryland. She currently serves on the communications committee for the Academy of Emergency Medicine Pharmacists.

By Nathan Lewis, MD; Ambika Anand, MD, MEHP; Carrie Maupin, MD; and Danielle Nesbit, DO, on behalf of the SAEM Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine academy

Did you hear the news? Emergency medicine is back to being a popular specialty! According to the most recently published 2025 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) data, the number of applicants is rising, and unfilled positions are declining. For many, this feels like a return to form for a specialty long considered a competitive and popular choice. But while the latest numbers bring some optimism, they tell an incomplete story. To fully understand the current landscape,

it’s important to examine the broader trends that led to this point.

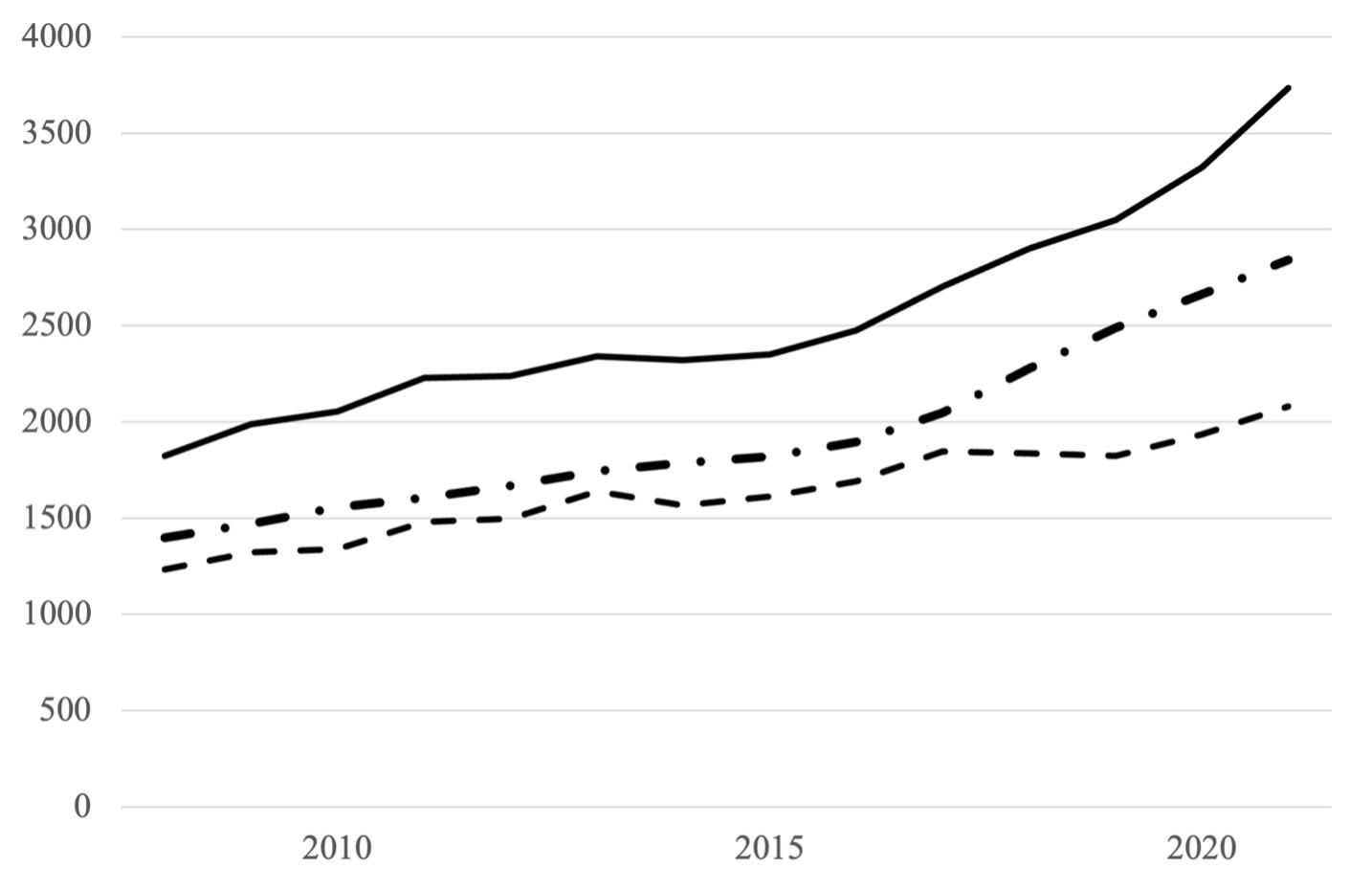

The Setup: Decades of Growth Data from the NRMP’s Results and Data and Charting Outcomes reports offer valuable insight. One of the most consistent patterns in the emergency medicine match has been growth—significant growth. In 2025, the number of available postgraduate year one (PGY-1) training positions offered by categorical emergency medicine

programs has roughly doubled since 2009 and more than tripled since the start of the 2000s. That growth has not been linear. A steeper increase in the number of positions offered annually began in 2017.

Although detailed data on all applicants is unavailable prior to 2008, trends since then show that the growth in applicants roughly mirrored the growth in available positions. Applicant numbers increased steadily from 2008 to 2016, then surged beginning in 2017.

“The applicant pool has diversified, with more Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine graduates and international medical graduates matching into emergency medicine.”

(Figure 1) This rise in both applicants and applications contributed to the perception of emergency medicine as a highly competitive specialty. For a field historically dominated by an allopathic match majority and an unfilled rate well under 1%, it is easy to see why.

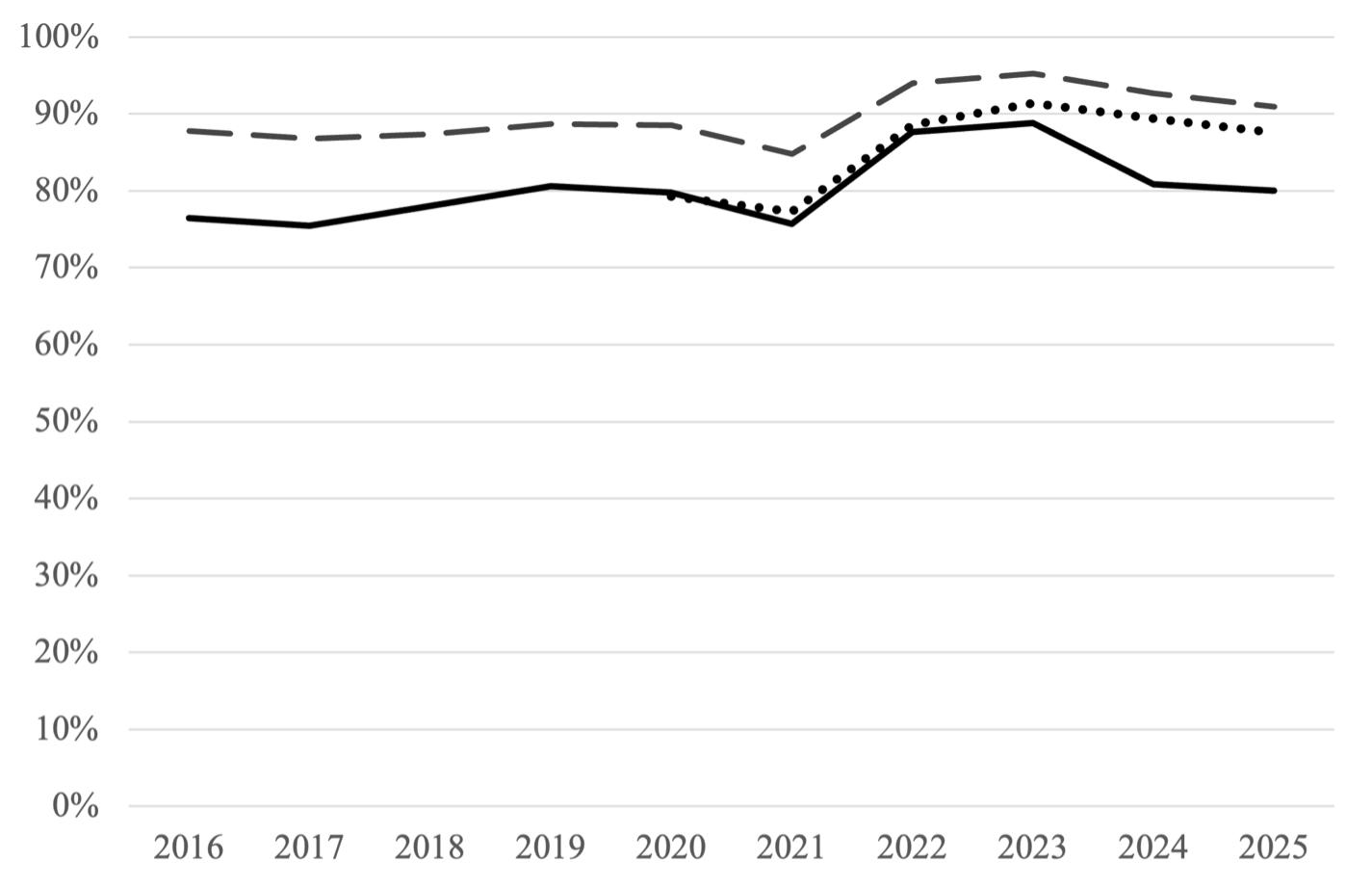

Despite this rapid expansion, most applicant groups continued to match successfully. Over the past 10 years, the proportion of U.S. Doctor of Medicine (MD) seniors applying to and matching in emergency medicine has remained steady—and even increased

slightly in the past five years. The same trend holds true for Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) senior applicants. (Figure 2) Additionally, the percentage of total matches accounted for by international medical graduates (IMGs) has steadily risen over the past five years, including the period prior to the 2023 Match.

The Crash: A Sudden Shift

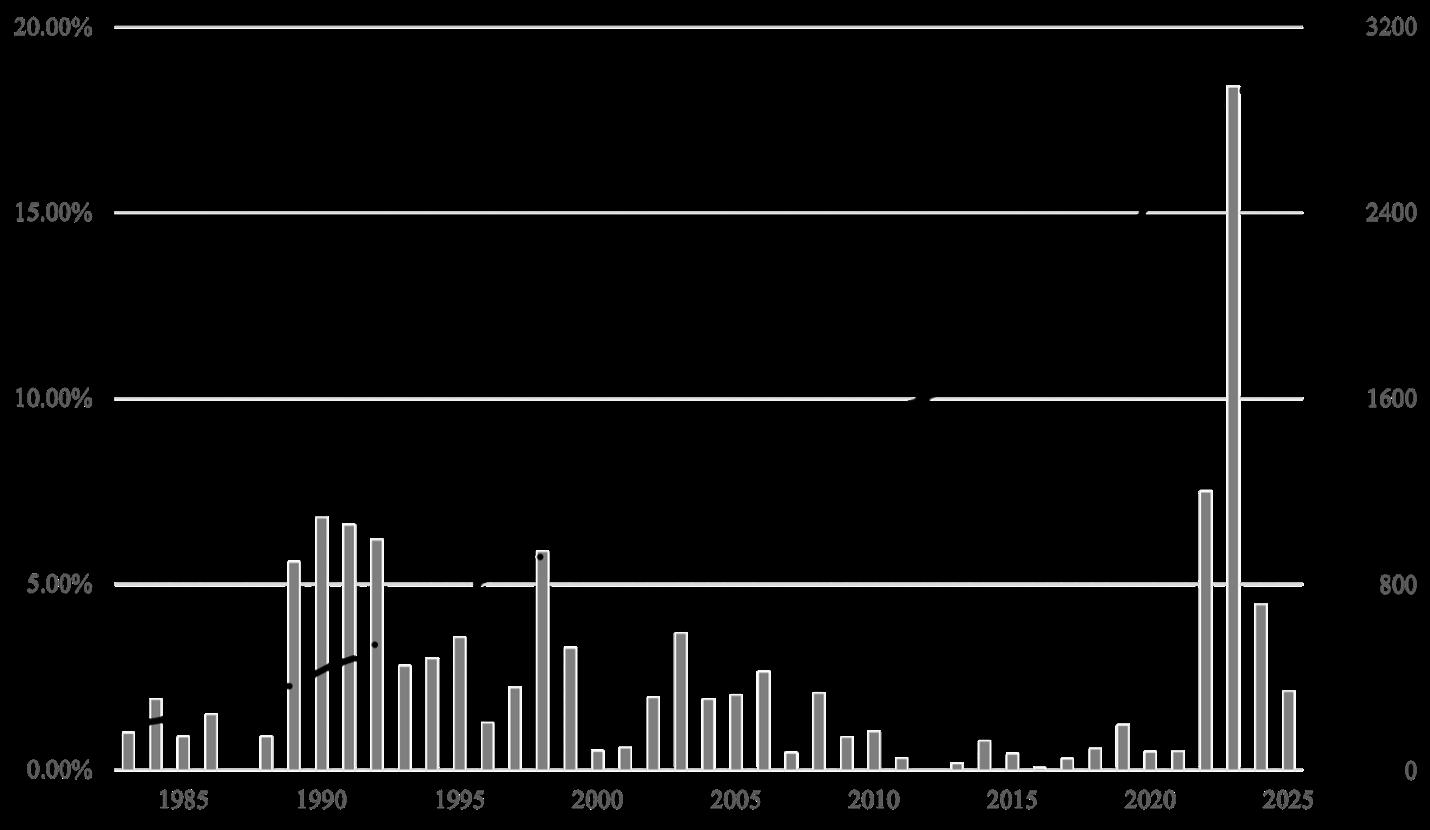

Although 2023 is remembered as the year emergency medicine saw a striking number of unfilled programs nationwide, the decline in applicants did not happen overnight. It began in 2021 and was already reflected in the

2022 Match. That year, the percentage of unfilled positions reached 7.5%, surpassing the previous all-time high of 6.8% in 1990. Then in 2023, the rate of unfilled positions exceeded 18%. (Figure 3)

In this unprecedented year, the total number of applicants fell short of the number of available training positions, and the unfilled rate climbed to nearly three times the previous record. This was a significant disruption for a specialty typically ranked among

continued on Page 31

Figure 2. Percentage of MD senior applicants (dashed line), DO senior applicants (dotted line; data unavailable prior to 2020), and all applicants (solid line) applying to emergency medicine who successfully match into EM from 2016 to 2025.

3. Number of offered PGY-1 training positions (dash-dotted line, right axis) overlaid on percentage of unfilled PGY-1 training positions (vertical bars, left axis) from 1983 to 2025.

“In 2023, the rate of unfilled positions exceeded 18%—a significant disruption for a specialty typically ranked among the top three or four in categorical match volume.”

CAREER CORNER

continued from Page 29

the top three or four in categorical specialties with the highest volume of matches.

Much speculation has emerged about the factors contributing to the 2023 Match outcome. Regardless of cause, students, medical schools, and program directors approached the 2024 cycle with anticipation and cautious optimism. The result was a clear rebound. Not only did emergency medicine overcome its applicant deficit, but the total number of applicants also returned to near-2021 levels.

However, the composition of the applicant pool shifted. Proportionally more DOs and IMGs matched into emergency medicine than in previous years.

Another notable change is in the number of applicants who preferred emergency medicine—meaning it was either the only specialty to which they applied or the top-ranked specialty in a dual-application strategy. Across Charting Outcomes reports released by the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) from 2007 to 2024, although the number of preferred emergency medicine applicants grew, it did so at a slower rate than the total applicant pool. In 2014, preferred EM applicants accounted for 91% of the entire applicant pool; in 2024, that figure fell to 83%. Further, the ratio of preferred applicants to available positions has declined—from 1.3 to 1 in 2007 to just under 1 to 1 in 2024.

This suggests that more applicants may now be considering emergency medicine as a backup option.

This year, the number of PGY-1 training positions again increased— though at a slower pace than in recent years—to a new high of 3,068. Applications also rose to 3,753, roughly equal to the 2021 total. Of those applicants, 40% were MD seniors and 33% were DO seniors. Among those who matched into emergency medicine, 46% were MD seniors, 36% were DO seniors, and 15% were IMGs. Just over 2% of positions went unfilled—half the unfilled rate in 2024. The NRMP has not yet released data on preferred specialties for 2025, and it remains to be seen whether these trends will continue.

The data from the 2025 Match indicate a second consecutive year of recovery for emergency medicine, with rising applicant numbers and fewer unfilled positions. However, this recovery tells only part of the story. The applicant pool has diversified, with more DOs and IMGs matching into emergency medicine. There also appears to be an increase in applicants ranking emergency medicine as an alternative to their first-choice specialty. Though still a minority, this trend may have long-term implications for program recruitment.

Is this good news for students? Absolutely. Emergency medicine has never been more welcoming to a broad and diverse group of applicants. The specialty’s growth over the past four decades underscores its resilience and enduring importance to the healthcare system.

Dr. Lewis is an associate professor at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, where he serves as emergency medicine clerkship director and assistant residency program director.

Dr. Anand is an assistant professor at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, where she serves as associate program director for the medical education fellowship.

Dr. Maupin is a second-year medical education fellow and clinical instructor in the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Emergency Medicine.

Dr. Nesbit is a first-year medical education fellow and clinical instructor in the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Emergency Medicine.

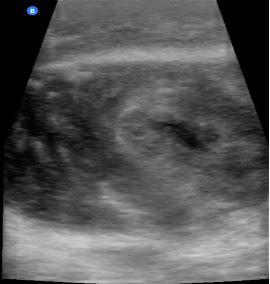

By Jacob Garrell, MD; Michael Sherman, MD; and Peter Hou, MD on behalf of the SAEM Critical Care Interest Group

If you have worked in a U.S. emergency department (ED), you are likely familiar with the growing challenge of ED boarding. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, ED patient volumes had increased more than 30% over the previous decade. From 2006 to 2014, the number of annual ED visits for critically ill patients rose from 2.8 million to 5.2 million.

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) defines boarding as the time after a patient has been admitted but before they are transferred from the ED. As hospital crowding worsens, critically

ill patients are increasingly boarding in the ED while awaiting intensive care unit (ICU) beds. These patients face unique risks, and the problem is intensifying as demand for critical care grows.

For ICU-level patients, the duration of ED boarding varies widely depending on institutional capacity and mitigation strategies. Multiple studies have shown that boarding beyond six hours is associated with increased mortality, with some reporting a 1.5% increase in risk of death for each additional hour a critically ill patient remains in the ED.

Recognizing this concern, the Society of Critical Care Medicine and ACEP formed the Emergency Department–Critical Care Medicine (ED-CCM) Boarding Task Force in 2017. Their findings revealed that ED boarding contributes to higher mortality, longer ICU stays, and increased ventilator use. The task force recommended action in three main areas: ED-based solutions, hospital-level strategies, and the development of resuscitation care units (RCUs).

continued from Page 33

One promising and broadly applicable solution is the implementation of a standardized handoff tool for ICU boarders. Transitions of care during ED shift changes are known risk points for medical error. Tools such as I-PASS have already demonstrated improvements in communication and patient safety in pediatric emergency settings and may serve as a model for similar handoff standardization. Applying a similar structure to ICU boarder handoffs between ED teams could reduce errors, boost efficiency, and improve outcomes. Regardless of whether an ED uses acuity cohorting, RCUs, or traditional layouts, handoff represents a common vulnerability—and an opportunity for improvement.

Research into existing handoff practices for ICU patients in adult EDs has revealed significant gaps

“Transitions of care during emergency department shift changes are known risk points for medical errors.”

in critical information. For example, documentation of code status, contingency plans, and completed interventions is often incomplete at the time of handoff These gaps underscore the need for structured approaches to mitigate the potential impact of ED boarding.

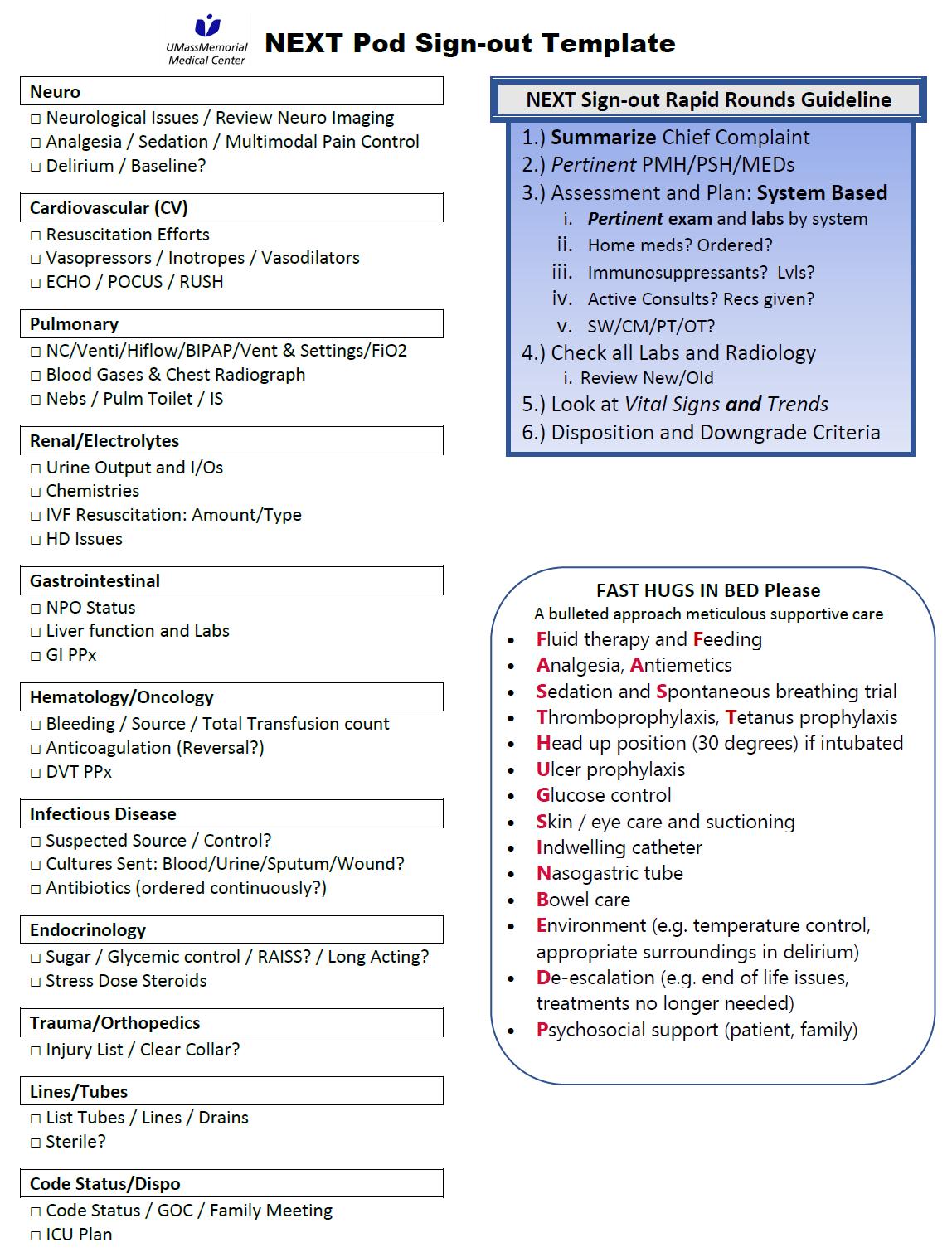

At UMass Memorial Medical Center’s University Campus in Worcester, Massachusetts—an urban tertiary care center that serves approximately 90,000 patients annually—critically ill patients frequently board in the ED due to high patient volumes and acuity.

To address the specific needs of this patient population, the hospital created a dedicated 9-bed RCU, known locally as the NEXT Pod. The unit is staffed by an attending physician and resident, with a low nurse-to-patient ratio. It routinely manages ICU-level patients awaiting transfer to inpatient critical care. It admits approximately 20 new highacuity patients daily, in addition to those transferred from other areas of the ED. ICU boarding times in the NEXT Pod vary, often exceeding 24 hours and spanning multiple ED shifts.

“Improving communication during the handoff of our most vulnerable patients is not just a quality improvement initiative—it is a frontline strategy to reduce morbidity and mortality in the emergency department.”

To reduce errors and improve care transitions in this complex environment, a multidisciplinary quality improvement team developed a rapid, systems-based ICU-style signout tool tailored for ED use. Designed by emergency medicine and EM/ critical care-trained physicians, the tool draws from traditional ICU rounds, incorporating structured systemby-system prompts and reminders for best practices—such as deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, timely antibiotic administration, continuation of critical home medications, and ventilator settings.

For ease of access, the tool was laminated and posted at computer workstations. Despite its formal nature, the tool was built for emergency department, with the goal of completing a flexible and rapid sign-out within 30 minutes.

The handoff tool was launched in fall 2024. Its impact was assessed using a de-identified survey based on the Feasibility of Intervention Measure (FIM) framework. The survey evaluated providers’ perceptions of:

• The existing handoff process

• The utility and usability of the new tool

• Integration with current ED workflows

• Provider comfort in managing ICUlevel patients

The survey also included an openended response section for additional feedback.

Results were largely positive. Nearly 93% of respondents agreed that the standard ED handoff process omitted important elements of care, especially

for the most complex patients. All respondents agreed that the new tool had the potential to reduce perceived errors in patient care. A salient finding was how feasible is a standardized handoff in an already chaotic setting. Notably, 78.5% of participants reported feeling more comfortable managing and signing out critically ill patients after using the tool.

The open-ended responses offered valuable insights beyond what was captured in the structured survey questions. Participants consistently expressed appreciation for the tool’s organized format and its alignment with expectations commonly seen in intensive care unit settings. However, a key concern also emerged: while the idea of standardization was widely supported, its successful implementation depends on having sufficient time, staffing, and, in some cases, adjustments to existing workflows. Several respondents noted that the handoff process added to their time burden and suggested that protected time or formal integration into shift schedules would be necessary to ensure consistent use.

Although this pilot study involved a small sample size, the early results suggest that a structured ICU-style sign-out tool adapted for emergency medicine can enhance care continuity, patient safety, and provider confidence during transitions of care from the ED to the ICU.

As ED boarding continues to worsen in the post-COVID landscape— particularly for ICU-level patients— low-cost, scalable interventions such as this may hold promise for both

academic and community settings. Further research involving larger sample sizes, longitudinal tracking, and potential integration with electronic medical records could help validate and refine the approach.

Improving communication during the handoff of our most vulnerable patients is not just a quality improvement initiative—it is a frontline strategy to reduce morbidity and mortality in the emergency department

Dr. Garrell is a postgraduate year three emergency medicine resident at the University of Massachusetts in Worcester with a growing interest in the care of critically ill patients in both emergency department and intensive care unit settings. He plans to pursue a fellowship in critical care medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Dr. Sherman is dual boardcertified in emergency medicine and critical care medicine and practices at Boston Medical Center. With experience working across multiple emergency department–intensive care unit and resuscitation care unit settings, his research focuses on resuscitation and ED-ICU operations. He has led numerous quality improvement initiatives and developed clinical practice guidelines at the intersection of emergency and critical care medicine.

Dr. Hou is dual board-certified in emergency medicine and critical care medicine. He practices at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Harvard Medical School. His research focuses on sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and COVID-19.

By Diana M. Bongiorno, MD, MPH; Jennifer Love, MD, MSCR; Joe-Ann Moser, MD, MS; Richelle J. Cooper, MD, MSHS; and Amy Zeidan, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine

Despite notable advancements, women in academic emergency medicine (EM) continue to face challenges related to pay equity, promotion, scholarly activity, and parental leave policies. A growing body of research is helping to better understand these persistent gender equity issues within the EM workforce.

To highlight key developments, members of the SAEM Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine (AWAEM) Research Committee conducted a literature

review of 2024 PubMed-indexed publications relevant to gender equity in EM. The committee reached a consensus on five top articles that provide timely insight. These studies cover a range of topics, including salaries of new EM residency graduates, chief resident selection, family-friendly policies, attrition rates, and women’s professional development programs.

Together, these articles offer evidence to guide the development and implementation of strategies for members of the Society for

Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) to promote gender equity within their departments.

Association of Gender and Personal Choices with Salaries of New Emergency Medicine

Graduates

Fiona E. Gallahue et al.

Methods: The authors sent a survey to over 2,000 graduating EM residents in 2019 that included questions about their demographics, perspectives on factors influencing their first job post-training, and base

“Compared to White men, women residents from underrepresented in medicine groups were half as likely to be chief residents.”

salary and characteristics of their first job. Quantile regression was used to analyze salary differences by gender while controlling for demographic, training, and first job characteristics.

Key Results: Among 258 graduating EM residents with completed surveys, the median first job salary was $30,000 higher for men versus women, even after adjusting for other factors. Women placed more importance on parental leave policy, proximity to family, and location/ setting in the job search, and less importance on salary, compared to men.

Limitations: A key limitation is the representativeness of the sample given only ~12% response rate among 2019 graduating EM residents.

Jennifer W. Tsai et al.

Methods: The authors analyzed data collected by the Association of American Medical College on EM graduates from 2017-2018. Binomial regression was used to analyze the relative risk of sex, and intersection of sex and racial and ethnic identity, on serving as chief resident, adjusting for USMLE Step 2 CK scores and clustering within residency programs.

Key Results: Compared to White men, women residents from underrepresented in medicine groups were half as likely to be chief residents. White women were significantly more likely to be chief

residents, relative to White men.

Limitations: The authors did not have data on residents who may have been selected for, but declined, the chief resident position, or on factors such as residency evaluations and test scores that may have influenced selection. Additionally, analyses could not account for the different ways in which chief residents are selected at different programs.

Consensus-Driven Recommendations to Support Physician Pregnancy, Adoption, Surrogacy, Parental Leave, and Lactation in Emergency Medicine

Michelle D. Lall et al.

“Among 258 graduating was $30,000 higher

graduating EM residents with completed surveys, the median first job salary higher for men versus women, even after adjusting for other factors.”

AWARENESS

continued from Page 37

Methods: The steps involved in developing consensus recommendations included: 1) a working group of members from the ACEP Well-Being Committee and SAEM AWAEM completing a literature review of parental leave and related policies, including relevant laws and national standards, and drafting initial recommendations; 2) recruiting 33 stakeholders from 11 national EM groups to participate in a consensus process that involved contributing additional recommendations and 3 rounds of voting to reach consensus; 3) incorporating feedback from focus groups and an open public comment period.

Key Results: This group developed 17 consensus-driven recommendations to assist departments with implementing family-friendly policies, including related to miscarriage, prepartum and peripartum periods, parental leave, and lactation.

Limitations: The consensus process involved a group of stakeholders which may not be representative of the EM workforce. The group did not consider the feasibility of implementing these recommendations as part of the consensus process and did not come to a consensus to make recommendations on fertility treatment, secondary parental leave, scheduling upon return to work, or childcare.

Rates of Emergency Medicine Residency Graduates by Gender

Nikita A. Salker et al.

Methods: The authors gathered lists of EM graduates from classes pre1990 to 2010 from 21 EM residency programs established before 2005.

In 2020, they collected data from state licensing board websites and other public websites (e.g. hospital websites, social media), including on state license status and hospital privileges. “Attrition” was defined as not currently working clinically in EM or an EM subspecialty.

Key Results: Among 3,725 EM physicians in the workforce at least 10-30 years following residency, attrition rate from clinical EM did not significantly differ by gender.

Limitations: It is possible that individuals may have been misclassified, as the authors did not contact individuals in the “attrition” group to ensure accurate classification. Graduates of programs included in this study may not be representative of the EM workforce, and trends among physicians graduating residency 10-30 years prior may not be the same as trends among more recent graduates.

Women's Professional Development Programs for Emergency Physicians: A Scoping Review

Stacey Frisch et al.

Methods: The authors conducted a systematic search of peer-reviewed literature related to women’s professional development groups for EM physicians. They extracted data on program leadership and objectives, funding sources, educational activities, meeting themes, and barriers encountered from the included studies.

Key Results: Data from 11 studies of 10 professional development groups for women in EM suggest these groups can have an important role in increasing mentorship, recognition, community, job satisfaction, and well-being. The authors summarize strategies to overcome potential

challenges related to facilitating attendance, ensuring sustainability, obtaining funding, and measuring impact.

Limitations: Some of the included studies were missing data on program characteristics of interest. The included programs were largely in academic institutions, limiting generalizability.

Dr. Bongiorno is a chief resident in the Harvard Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency at Mass General Brigham. In July, she will begin a research fellowship in the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Love is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. She also serves as the vice president of education for the Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine.

Dr. Moser is an assistant professor and assistant residency program director at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She also serves as co-chair of the Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine Research Committee.

Dr. Cooper is a professor of emergency medicine and vice chair of research at the UCLA Department of Emergency Medicine. She is also executive deputy editor at Annals of Emergency Medicine.