Emergency Medicine Through Leadership, Research, and Mentorship

An interview with Lewis S. Nelson, MD

Emergency Medicine Through Leadership, Research, and Mentorship

An interview with Lewis S. Nelson, MD

Exploring the R38 Mechanism: A Research Training Opportunity for Medical Residents

Ali S. Raja, MD, DBA, MPH SAEM President Massachusetts General Hospital

Harvard Medical School

Board Liaison to:

• Bylaws Committee

• Telehealth Interest Group

• Wilderness Medicine Interest Group

Pooja Agrawal, MD, MPH

Member at Large

Yale Department of Emergency Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Ethics Committee

• Research Committee

• Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine (ADIEM)

• Informatics, Data Science, and Artificial Intelligence Interest Group

• Research Directors Interest Group

• Sex and Gender in Emergency Medicine Interest Group

• Tactical and Law Enforcement Interest Group

• Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department (GRACE)

Nicholas M. Mohr, MD, MS

Member at Large University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Equity and Inclusion Committee

• Program Committee

• Simulation Academy

• Disaster Medicine Interest Group

• Evidence-Based Healthcare & Implementation Interest Group

• Transmissible Infectious Diseases

Interest Group

• Advanced Research Methodology Evaluation and Design (ARMED)

Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS SAEM President-Elect Emory University

Board Liaison to:

• RAMS Board

• Nominating Committee

• Committee of Academy Leaders (COAL)

• Academy of Geriatric Emergency Medicine

• Educational Research Interest Group

• Operations Interest Group

Jeffrey P. Druck, MD

Member at Large University of Utah School of Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• Awards Committee

• Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine

• Academic Emergency Medicine Pharmacists Interest Group

• Toxicology/Addiction Medicine Interest Group

• Certificate in Academic Emergency Medicine Administration (CAEMA)

Ava Pierce, MD

Member at Large UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas

Board Liaison to:

• Education Committee

• Workforce Committee

• Academy of Women in Academic Emergency Medicine

• Behavioral and Psychological Interest Group

• Oncologic Emergencies Interest Group

• ARMED MedEd

Jody A. Vogel, MD, MSc, MSW SAEM Secretary-Treasurer Stanford University

Board Liaison to: • Global Emergency Medicine Academy • Finance Committee • Airway Interest Group

• Social Emergency Medicine and Population Health Interest Group

Julianna J. Jung, MD, MEd

Member at Large

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Board Liaison to:

• 2025 Consensus Conference Committee

• Fellowship Approval Committee

• Grants Committee

• Academy of Administrators in Academic Emergency Medicine (AAAEM)

• Clinical Researchers United Exchange (CRUX) Interest Group

• Palliative Medicine Interest Group

• Emerging Leader Development Program (eLEAD)

Lewis S. Nelson, MD, MBA Chair Member

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

Board Liaison to:

• Consultation Services Committee

• Quality and Patient Safety Interest Group

• Vice Chairs Interest Group

• Chair Development Program

Daniel N. Jourdan, MD

Resident Member Henry Ford Hospital

Board Liaison to:

• Wellness Committee

• Climate Change and Health Interest Group

• Innovation Interest Group

• Neurologic Emergency Medicine Interest Group

Wendy C.

MD SAEM Immediate Past President UCLA Department of Emergency Medicine

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Ryan LaFollette, MD

Member at Large University of Cincinnati

Board Liaison to:

• ED Administration and Clinical Operations Committee

• Faculty Development Committee

• Membership Committee

• Academy of Emergency Ultrasound (AEUS)

• Critical Care Interest Group

• Emergency Medical Services Interest Group

• Pediatric Emergency Medicine Interest Group

to:

• SAEM Executive Committee

• Association of Academic Chairs of Emergency Medicine (AACEM)

• RAMS Board

• SAEM Foundation

in

Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital 2024-2025 President, SAEM

As I reflect on our incredible progress in 2024, I want to express my heartfelt gratitude to all SAEM members and staff for their unwavering commitment to academic emergency medicine. Your dedication has propelled SAEM to new heights, making this year one of transformational growth and visionary leadership. Together, we’ve continued to break records, innovate, and shape the future of our specialty. Let’s take a moment to celebrate the many accomplishments of 2024.

In 2024, SAEM achieved a historic milestone with 9,200 members — a nearly 34% increase over the past five years. This remarkable growth reflects the strength of our community and our ability to bring together diverse professionals at all career stages.

SAEM24, held this past May in Phoenix, was our largest and most successful annual meeting to date. It featured the highest number of submissions ever for didactics, abstracts, innovations, and clinical images. With over 3,900 attendees—a record—this event showcased groundbreaking research, innovative educational content, and dynamic networking opportunities. Key highlights included our largest-ever SonoGames competition, which attracted a record 105 residency programs, as well as new workshops focused on addressing critical issues in emergency medicine.

The SAEM Foundation achieved remarkable milestones in 2024, awarding $1 million in grants—its largest funding

SAEM members, your extraordinary efforts made 2024 a banner year for our Society! Your dedication, engagement, and active participation have driven SAEM’s continued growth and success, shattering records across the board, including:

Highest membership numbers in SAEM’s history.

Record-breaking attendance at the SAEM24 annual meeting.

Unprecedented submissions for abstracts, didactics, workshops, innovations, and clinical images for SAEM24. Most committee interest forms ever submitted.

Record-setting award nominations.

We are incredibly grateful for all you’ve contributed to these remarkable achievements. As we step into the new year, let’s build on this momentum together.

total ever—to support 30 researchers and educators in academic emergency medicine.

In May 2024, SAEMF received a transformative $1 million commitment from SAEM, significantly enhancing resources for advancing emergency medicine research. This major donation coincided with a 58% surge in grant applications, underscoring the growing demand for research funding in the field.

Additionally, SAEM raised a record $104,015 for emergency medicine through this year’s Academy, Committee, and Interest Group Challenge and introduced two groundbreaking RAMS funding opportunities: the Ali and Danielle Raja RAMS Medical Student Research Grant and the David E. Wilcox, MD, FACEP Scholarship.

These initiatives are important steps forward in supporting research and career development for future leaders in emergency medicine.

SAEM’s journals continue to thrive thanks to the dedicated efforts of their editorial boards, reviewers, and authors.

Both journals experienced an increase in submissions in 2024, with Academic Emergency Medicine (AEM) showing a notable 27% growth. AEM remains a leading journal in the field, retaining its position as one of the largest peerreviewed publications in emergency medicine.

Academic Emergency Medicine Education and Training (AEM E&T), which received its first Impact Factor™ in 2023, continues to grow steadily, with a consistent rise in submissions.

Addressing a critical gap in nonopioid use disorder treatment, SAEM published the fourth Guideline for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department (GRACE) series, SAEM GRACE-4: Alcohol Use Disorder and Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome Management in the Emergency Department

In 2024, SAEM expanded its efforts to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) through several impactful initiatives and resources. Among these, the SAEM Board of Directors issued a strong statement in April opposing the EDUCATE Act. The statement emphasized that the proposed bill disregards the essential role of DEI initiatives in advancing health equity and improving patient outcomes.

Other 2024 SAEM community-developed DEI initiatives included:

• Expanded Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Curriculum: Four new chapters were added:

- Ableism

- Intersectionality

- Identity-First Language

- Dealing with Racist or Bigoted Patients and Colleagues

• SAEM24 Consensus Conference: The conference, themed “Creating a Diverse and Sustainable Emergency Medicine Investigator Pathway,” focused on establishing a robust and diverse pipeline of federally funded clinicianscientists in emergency medicine.

• SAEM EM Mentorship and Pathway Program Directory: A comprehensive guide designed to help address health disparities, strengthen the emergency medicine pipeline, and cultivate the next generation of diverse professionals.

• DEI Glossary of Terms: A resource aimed at fostering inclusive dialogue and a deeper understanding of key DEI concepts.

• Leadership, Engagement, and Academic Pathway (LEAP): A program designed to support and encourage academic careers in emergency medicine.

continued on Page 6

• SAEM DEI Resource Library: A free online platform featuring articles, books, videos, and other educational materials on DEI topics such as the history of discrimination, patient care disparities, and faculty diversity.

Through these initiatives, SAEM reinforced its dedication to fostering a more equitable and inclusive emergency medicine community.

In 2024, 400 members authored more than 170 SAEM Pulse articles, contributing to a 46% growth in submissions from the previous year. To accommodate this growth, SAEM Pulse implemented several changes in 2024:

• A clear publication mission statement to guide future content.

• Updated SAEM Pulse Submission Instructions and Writer Guidelines, aligning with best practices and streamlining the submission process.

• An automated submission form to replace the previous email system, simplifying submissions, reducing errors, and speeding up turnaround times.

In 2024, SAEM’s academies, committees, and interest groups reaffirmed their dedication as leaders and innovators in emergency medicine (EM) education and research, contributing prolifically to the field. These included over 50 webinars, a record 170 SAEM Pulse articles, as well as curricula, didactics, abstracts, toolkits, podcasts, and more. This community-generated content brings diverse perspectives and insights, enriching the collective knowledge base and providing valuable resources for continuous learning and professional development.

Participation and engagement within SAEM saw remarkable growth in 2024, highlighted by a nearly 20% increase in committee sign-ups. SAEM also launched a new tier system for interest groups, complete with a checklist to guide groups aspiring to achieve Academy status. To further strengthen community connectivity, the transition to the HigherLogic Thrive platform enhanced the user experience with features such as a centralized social feed, streamlined navigation, and improved resource accessibility.

Here is a selection of the newest and noteworthy educational highlights from SAEM’s community groups:

• Comprehensive Fall Risk Assessment and Prevention Literature

• Boarding and Crowding Toolkit

• Roadmap to Emergency Medicine Research Funding

• Social Emergency Medicine Integrated Network for Advancing Research (SEMINAR)

• Securing Your First Faculty Position: A Guide for Residents and Fellows

• Roadmap to Emergency Medicine Research Funding

• Emergency Medicine Interest Group (EMIG) Guide: Curriculum & Handbook

• Biostats Made Simple, Sessions 1-6

In partnership with the NIH Office of Emergency Care Research and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Neuro-EM Scholars National K12 Program was launched in 2024 to recruit, mentor, and train early-career EM faculty in neurological disorder research. The program also emphasizes diversity and encourages participation from underrepresented backgrounds. SAEM’s strategic approach and partnerships in this initiative represent a pivotal moment for progress and innovation in EM research.

Thank you for being part of this extraordinary journey. I’m incredibly proud of all we achieved together in 2024. From record-breaking growth to innovative programs and research funding, SAEM remains at the forefront of academic emergency medicine. I encourage you to explore the many resources available to you as a member and stay engaged as we continue to shape the future of our specialty. Here’s to an even brighter 2025!

ABOUT DR. RAJA : Ali Raja, MD, DBA, MPH, is a professor of emergency medicine at Harvard Medical School and the deputy chair of the department of emergency medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital.

We’re immensely grateful for your contributions in 2024 and invite you to continue this exciting journey with us as we enter the new year! Here are ways for you to make an impact on the future of SAEM:

• Renew your membership: SAEM offers a range of membership benefits tailored to every stage of your career. Renew your membership today and make the most of what SAEM has to offer!

• Attend SAEM25: Join us May 13-16, 2025, in Philadelphia for top-tier educational content, networking, and career development in academic EM. Register today!

• Run for a leadership position in 2025: Consider nominating yourself for a society-wide elected office.

• Submit your work: Share your research and insights through publications like AEM or AEMET, Pulse, or by submitting your work for the SAEM annual meeting

• Attend a regional meeting: Participate in an SAEM Regional Meeting to share your research, receive/provide mentorship, and network with others in your area.

Washington University in Saint Louis

2024-2025 RAMS Board President

It’s hard to believe we’re already halfway through the academic year! So much has happened in the past few months: for our resident members, the 2024 fellowship match results have been announced and for our medical students, interviews for the 2025-2026 residency match season are drawing to a close. In my own program, I’ve had the opportunity to meet and interview many medical students who are emergency medicine-bound. I have been consistently impressed by the incoming class of emergency physicians I have met on the interview trail. They are diverse, accomplished, and enthusiastic about our specialty. The future of our field is bright.

The Resident and Medical Student (RAMS) board continues its work for you. In our ongoing efforts to increase membership engagement, we are actively seeking more opportunities for RAMS involvement within SAEM’s committees and academies. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend joining an academy or interest group to engage in the subspecialty work that most interests you and to connect with faculty mentors who are national leaders in their fields. As part of your SAEM membership, RAMS members can join an academy or interest group at any time for free. For those of you already involved in committee, academy, and/or interest group work, let us help you promote your opportunities for RAMS participation!

The RAMS board has exciting plans for the coming months. We will soon finalize our strategic plan for 20252027, setting our agenda to develop RAMS into leaders in academic emergency medicine. Additionally, we will host several webinars focused on professional development, including topics such as creating your residency rank list, transitioning from medical school to residency financially, and navigating the evolving landscape of medical technology in the clinical setting. If you can’t attend a webinar when it’s live, all past webinars are available on the SAEM website

Finally, RAMS board elections for 2025-2026 will open on January 27. As chair of the nominating committee this year, I’ve enjoyed reviewing the candidate packets for the upcoming election cycle. We have an outstanding slate of candidates, and I’m excited to see who will serve on the RAMS board next year. Be sure to check your email and SAEM account so your election ballot can be counted!

SAEM 25 in Philadelphia is just a few short months away. I look forward to seeing you all there!

ABOUT DR. CLOESSNER: Emily “Ly” Anne Cloessner, MD, MSPH, is a current PGY-4 and chief resident at Washington University in Saint Louis.

“The incoming class of emergency physicians is diverse, accomplished, and enthusiastic about our specialty. The future of our field is bright.”

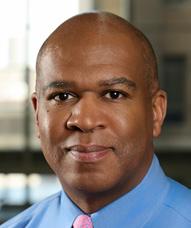

Lewis S. Nelson, MD, is a professor and chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark, New Jersey, and chief of the Division of Medical Toxicology at University Hospital. In January 2025, he will assume the role of dean at the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine at Florida Atlantic University.

Board-certified in emergency medicine, medical toxicology, and addiction medicine, Dr. Nelson has built a distinguished career in academic leadership and clinical expertise. Prior to his tenure at Rutgers, he served as vice chair for academic affairs and director of the medical toxicology fellowship at New York University School of Medicine.

Dr. Nelson’s leadership extends to several national organizations. He has served as a director of the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM), president of the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT), chair of the Medical Toxicology Subboard, and president of the Association of Academic Chairs in Emergency Medicine (AACEM). Additionally, he has contributed to the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and currently holds the position of chair on the board of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM).

An influential academic, Dr. Nelson is an editor of Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies and serves on the editorial boards of Annals of Emergency Medicine and the Journal of Medical Toxicology. His research focuses on the medical and social consequences of substance use, particularly opioid overdose, alcohol withdrawal, and alternative pain relief strategies. His work has significantly shaped health policy on substance use, clinical care across healthcare settings, and education for learners at all levels.

Dr. Nelson has received numerous honors, including the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Award for Outstanding Contribution in Research (2023), NJMS Faculty of the Year (2018), and the ACMT Career Achievement Award (2018). He has also been a long-standing consultant to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Health and Human Services (DHS), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

A graduate of the State University of New York Health Science Center at Brooklyn (Downstate), Dr. Nelson completed his emergency medicine residency at Mount Sinai School of Medicine and a fellowship in medical toxicology at New York University School of Medicine. He also holds an MBA from Brandeis University.

Dr. Nelson’s career is defined by his dedication to advancing emergency medicine, medical toxicology, and public health through leadership, research, and service to the academic emergency medicine community.

What inspired you to join SAEM, and what aspects of the organization’s mission resonate most with you?

As a career academic clinician, SAEM’s focus on the role of education, research, and faculty development in improving patient outcomes represent what I value most.

As a current SAEM board member, what do you value most about the organization’s role in advancing emergency medicine education and research?

I most value SAEM’s focus on our members’ career interests and needs by providing platforms, such as committees and interest groups, to grow and engage with colleagues and leaders. I also highly appreciate the SAEM’s extensive collaboration within and outside the organization to tackle issues critical to the advancement of our specialty, such as faculty development and emergency department (ED) boarding.

What unique expertise or insights do you bring to the board, and how do you plan to contribute to addressing the challenges facing both our specialty and the organization?

I am the inaugural “chair member,” which represents an ex officio role for the past president of the Association of Academic Chairs in Emergency Medicine (AACEM). I bring

my perspectives as a long-standing chair who has other organizational leadership roles to (hopefully) enhance SAEM’s role as a member-centered, externally facing service organization.

What do you hope to achieve during your term on the board, and how do you see these contributions advancing SAEM’s strategic goals?

SAEM is a strong, member centered organization with diverse goals, nearly all of which reflect those of an academic chair. I am most interested on improving the pipeline of faculty with research skills, which is also a focus of AACEM, and on addressing faculty career satisfaction and longevity.

In your opinion, what role does SAEM play in shaping the future of emergency medicine, and how can the organization expand or strengthen that role?

By providing opportunities for communicating with likeminded colleagues, SAEM plays a key role in promoting critical thinking about our concerns and strategic thinking about solutions. The annual meetings, the online

“The emergency department, which serves as the face of the health care system to every community, is the first touch point for many patients with a substance use disorder.”

continued from Page 9

communities, and the active committee structure provides fertile ground on which to grow collaboration that set the trajectory for the future.

Are there specific SAEM programs or initiatives that have had a significant impact on your professional growth or practice?

SAEM’s focus on professional development has been highly instrumental in my career development, particularly in the second half of my career. Participation in the Chair Development Program (CDP) and my deep involvement with the affiliated AACEM have provided learning, skill-building, and networking opportunities that are hard to find anywhere else.

What emerging trends or challenges do you foresee in managing substance-related emergencies, and how can emergency medicine educators better prepare clinicians to address these issues?

No communities have been immune to the grasp of the substance use crisis. The ED, which serves as the face of the health care system to every community, is the first touch point for many patients with a substance use disorder. This optimally positions us with the opportunity to engage these patients in a consideration of the personal and social consequences of their disease and to provide support for them to seek treatment. In addition, the funding environment from federal agencies interested in investing in low barrier ED programs is favorable for clinicians championing ED based care. Unlike most other diseases, in which a plethora of systems and clinicians exist to manage their disorder, the substance-using population is marginalized and disconnected, lacks adequate access and funding for care, and is challenging to study due to structural issues, such as poor follow up.

Your research addresses critical topics like opioid management and medication safety. How can emergency medicine academicians translate these research findings into real-world practice while maintaining patientcentered care?

As a specialty we have stepped up and made incredible progress in identifying patients with or at risk for substance-use related consequence and engaged

Dr. Nelson explaining the uses and toxicity of the mayapple plant.

them in both short term and longitudinal treatment. For example, we have metered our opioid prescribing, distributed or prescribed naloxone, and created navigator programs to get our patients the care that they need to recover. All of these are evidence-based strategies that make sense. Burgeoning within the specialty is a focus on other substances, particularly alcohol and stimulants. We have clearly taken ownership of this societal concern and made great strides to address it.

Looking ahead, what areas of medical toxicology or emergency medicine research hold the greatest potential to transform the field?

One of the best parts about both specialties is that there are an endless number of research opportunities that can transform both the specialty and healthcare. Academic emergency physicians and medical toxicologists are

involved in basic science, clinical and translational, epidemiological, health services, and many other important venues. Substance use research reaches beyond opioids, and is increasingly focused on alcohol and alcohol withdrawal, stimulants, novel psychoactive substances, cannabis, and those less acutely consequential, such as nicotine. Well initiated, evidence-informed care in the ED for patients with common poisonings such as acetaminophen, carbon monoxide, or snakebite will pay dividends in improving healthcare outcomes.

You’ve held leadership roles in organizations like the American College of Medical Toxicology, AACEM, and SAEM. What lessons have you learned about leading change in academic emergency medicine?

As John Donne famously said, “No man is an Island,” and that is increasingly true of success in academic health care. Without a team, collaboration, communication, and trust, we will never optimize progress. Helping those to whom I am accountable identify and act on their interests is an important part of academic leadership.

What strategies have you found most effective for fostering collaboration and innovation among faculty, residents, and students?

Providing both opportunity and support that allow people to succeed (and occasionally fail, which is ok) has proven to be a successful approach. We choose academic healthcare because we enjoy making positive change in things about which we are passionate. Research and scholarship are daunting without the right infrastructure, which is a departmental expectation to support. This includes making mentorship connections, vetting research ideas, thinking through methodological strategies, allocating statistical and informatics effort, and providing operational support. Mentorship is key in academic medicine. What role does mentorship play in your vision for emergency medicine, and how do organizations like SAEM support these efforts? Mentorship is a skill that is honed through interpersonal engagement and academic collaboration. SAEM provides an environment to foster growth of these skills both through its formal educational activities and opportunities for relationship building.

Please complete the following three sentences:

1. In high school, I was voted most likely to thrive in settings of controlled chaos.

2. A song you’ll find me singing in the shower is (Have you heard me sing? I hum a repertoire of Beatles music.)

3. A quote I live by is “It’s all relative.”

Who would play you in the movie of your life and what would that movie be called?

Neil Patrick Harris in “Doogie Becomes a Dean.”

If you could invite three people, past or present, to your dream dinner party, who would be on the list?

1. Larry David, comedian, actor, writer and television producer.

2. Serena Williams, former professional tennis player, widely regarded as one of the greatest of all time

3. Stephen Dubner, journalist, podcaster, radio host and author of the popular “Freakonomics” book series

What is your guiltiest pleasure (book, movie, music, show, food, etc.)?

Twice a day ice cream (even when not on vacation).

You have a full day without any obligations — how do you spend it?

Being outside, doing anything, perhaps getting in a run or catching up on work (particularly during a thunderstorm!).

What tops your bucket list?

Wine tasting in Tuscany with my family. What's one thing few people know about you?

My ringtone is “Frolic “(the “Curb your Enthusiasm” theme song).

By Danielle Haussner, MD; Catrina Cropano, MD; Michael Redlener, MD; Samuel E Sondheim, MD, MBA; Amos J. Shemesh, MD; and

Mark Hanna, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Disaster Medicine Interest Group and the SAEM Administration and Operations Committee

Ensuring Emergency Department Preparedness During Downtime

As health care continues to undergo rapid digital transformation and increasingly relies on technology to function, cyber disruptions have emerged as a significant threat to hospitals. These attacks can compromise protected health information, disable electronic medical records (EMRs), disrupt medical devices such as pumps,

monitors, and ventilators, and hinder essential communication systems, including internet and phone networks. Downtime, defined as the failure or unavailability of technological systems, can severely disrupt workflows, impact patient outcomes, and lead to substantial financial burdens.

Emergency departments (EDs) are especially vulnerable because they provide 24/7 urgent and emergent

care to undifferentiated patients. Preparing for unplanned and prolonged downtime is essential. Cyber disruptions are no longer hypothetical but inevitable, as demonstrated by recent high-profile incidents. A ransomware attack disabled Staten Island’s Richmond University Medical Center’s EMR for three weeks, while a 2024 attack on Ascension left its EMR inoperable for six weeks.

“With 386 health care cyberattacks reported this year to date, the need for robust downtime procedures in emergency departments is more critical than ever.”

Real world casualties of unplanned downtime events include canceled surgical procedures, rerouted emergency medical services (EMS) patients, and inaccessible medication terminals. Beyond operational impacts, unplanned downtime carries devastating financial risks. A single data breach in health care costs an average of $11 million, encompassing system recovery, data restoration, and legal liabilities. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights imposes substantial penalties for violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). For instance, the Change Healthcare cyberattack caused significant disruptions, with 74% of affected hospitals reporting impacts

on patient care and 94% reporting financial losses. Among hospitals hit by ransomware attacks, 53% reported increased mortality rates, and 54% were unable to provide full patient services.

With 386 health care cyberattacks reported this year to date, the need for robust downtime procedures in emergency departments (EDs) is more critical than ever. This article outlines key strategies for ED operations leadership to address these challenges and maintain care delivery during such disruptions, drawing on experiences from NewYorkPresbyterian and Mount Sinai Health Systems in New York City.

Addressing Planned vs. Unplanned Downtime

EDs are adept at managing planned EMR downtimes, which are typically scheduled during overnight hours when patient volumes are lower. These planned interruptions allow for strategies such as minimizing patient movement, placing bulk orders before the shutdown, coordinating communication among multidisciplinary teams, and completing documentation once systems are restored. However, while effective for scheduled events, these strategies are insufficient for unplanned or prolonged downtimes, exposing a significant gap in preparedness. As the frontline of health care, EDs must be equipped to maintain operations during

continued on Page 15

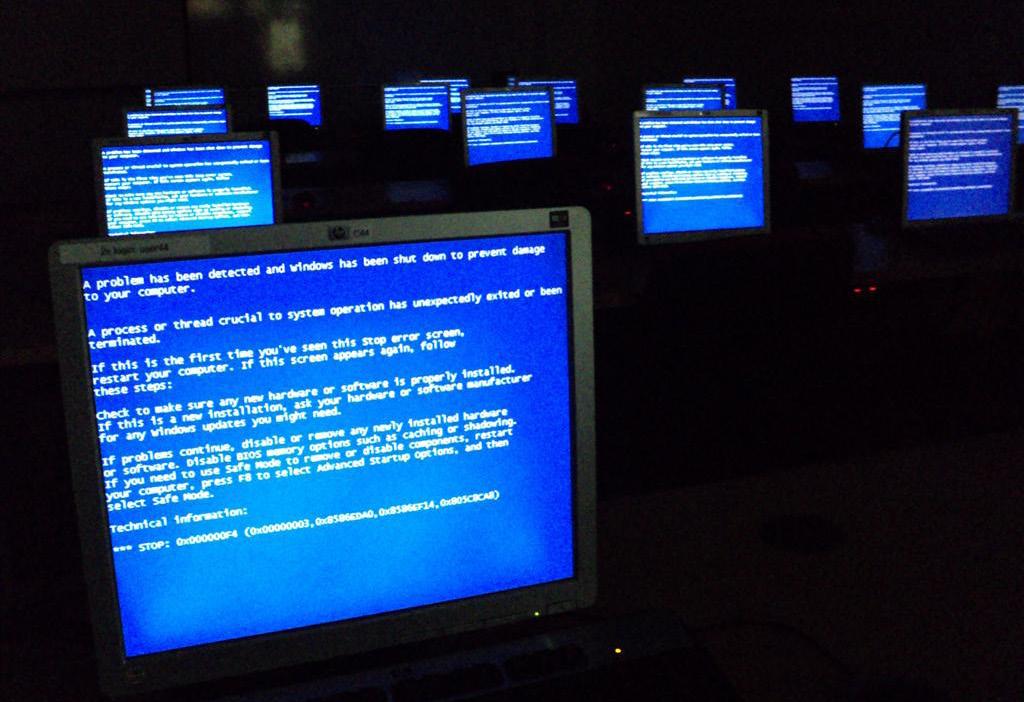

Figure 1. Downtime checklist for clinical administrator.

continued from Page 13

unforeseen disruptions. Notably, in 2023, the average duration of unplanned downtimes caused by ransomware attacks was 18.7 days.

For unplanned downtime events, procedures should be initiated at the 20-minute mark. A clinical administrator, such as a physician or nursing leader, should lead a huddle to update staff, activate downtime processes, and escalate the issue to departmental and hospital leadership. Using a checklist-based framework, such as the Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) model, ensures essential actions are taken to sustain care delivery effectively. For reference, see Figure 1, which provides an example checklist from Mount Sinai Morningside and Mount Sinai West.

A downtime cart (Image 1), equipped with preassembled patient charts and standardized documentation, is essential. These materials should include forms for lab orders, medications, imaging, nursing actions, provider notes, progress notes, and consent forms. Checklist-style order forms ideally list commonly ordered items with standard dosing, frequency, delivery methods, etc. to reduce ordering errors and to improve efficiency. Specialized binders for codes and notifications like cardiac arrest, trauma, stroke, and sepsis should also be prepared. Provider notes should align with 2023 evaluation and management (E/M) coding updates to facilitate streamlined documentation and billing.

To track patient movements during downtime, a rolling whiteboard with room numbers, and dry-erase markers can help maintain real-time changes in patient movements. For transparency, patients should be informed of the downtime and its potential impact by a dedicated patient notification team, ideally involving nursing leadership and patient services.

Pharmacy and nursing staff should manage the automated medication dispensing system (e.g., Pyxis) in override mode, manually verifying each medication issued to ensure accuracy. ED providers should have access to the imaging system (e.g., PACS) to review available images, with radiologists either present in the clinical space for formal interpretations or providing reliable communication for all reads. Critical radiology and laboratory results must be reliably and promptly communicated to providers via telephone. On-call directories should be regularly updated to facilitate easy access to consultants or admitting teams, with clearly defined escalation paths and backup contacts available. Overhead announcements should be used for codes and notifications to ensure timely team coordination and response.

A readily available library of preprinted discharge instructions for common chief complaints should be accessible for distribution to patients at discharge. Providers should also be supplied with prescription sheets that comply with state regulations for issuing discharge medications. After patient disposition, all charts should be finalized and submitted to the medical records team for proper processing.

Downtimes can be challenging for ED providers, staff, and patients, but proactive planning and welldesigned strategies can minimize their impact and ensure continuity of care until systems are restored. Key steps include implementing structured huddles, utilizing checklists, providing intuitive prebuilt materials, establishing clear workflows and communication channels, and coordinating protocols across ancillary and consult services. Each site should customize downtime protocols to meet its specific structure and operational needs.

A formal downtime committee with representatives from multiple sites fosters collaboration, standardization, and the exchange of best practices. Regularly conducting and refining

downtime drills further strengthens preparedness. By adopting these strategies, EDs can cultivate a culture of readiness and continue to deliver high-quality emergency care, even during the most disruptive events.

Dr. Haussner is an assistant attending physician in the department of emergency medicine at NewYorkPresbyterian Weill Cornell Medicine and a fellow in healthcare leadership and management. She can be reached at dbm9003@med.cornell.edu

Dr. Cropano is an assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and serves as the medical director for the Mount Sinai Beth Israel emergency department and as associate medical director for the Mount Sinai West emergency department. She can be reached at catrina. cropano@mountsinai.org

Dr. Redlener is an associate professor in the department of emergency medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and serves as the medical director for the Mount Sinai West emergency department. He can be reached at michael. redlener@mountsinai.org

Dr. Sondheim is an assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and serves as the assistant medical director for the Mount Sinai Morningside emergency department. He can be reached at samuel.sondheim@mountsinai.org

Mark Hanna, MD, is an assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine (in pediatrics) at the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia and the director of disaster preparedness for NYP-West. He can be reached at mh4401@cumc.columbia.edu

Dr. Shemesh is an assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medicine and serves as the director of clinical and faculty affairs. He can be reached at ajs9039@med.cornell.edu

By K. Robert Thompson III, MD, MBA and James Summers, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Administration and Operations Committee

The University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine is home to the nation’s first emergency medicine residency and provides emergency care at two hospitals in the UC Health System. The University of Cincinnati Medical Center (UCMC) is a tertiary referral center, a Level-1 Trauma Center, and the safety-net hospital for Southwest Ohio, handling an annual volume of 65,000 patient encounters. West Chester Hospital (WCH), a suburban community hospital and Level-3 Trauma Center, manages an annual volume of 43,000 patient encounters.

To address growing patient volume and waiting times, the UC

Department of Emergency Medicine implemented various initiatives, with mixed success. Ultimately, "Triage Protocols" were established at both UCMC and WCH. These protocols allow nursing staff to collect designated diagnostics (e.g., labs, electrocardiograms, X-rays) based on the chief complaint. However, as post-pandemic boarding burdens increased, the department faced higher-acuity patients in the waiting room and a rising number of patients leaving without being seen (LWBS), often without the ability to address concerning results.

In August 2022, the Provider in Triage (PIT) model was launched at

UCMC. The primary goal was patient safety, particularly addressing significantly abnormal lab values and conducting more targeted evaluations of waiting room patients. Several operational changes were required to implement this project. First, the 12-bed fast-track pod was converted into a standard acuity pod. Two large rooms were then transformed into vertical care areas with three loungers separated by curtains to treat lower-acuity patients. Attending staffing was adjusted to cover these new care areas, enabling the redeployment of Advanced Practice Providers (APPs) from the fast-track area to PIT, where

“The value of having more patients seen by a provider, even if they leave before treatment completion, cannot be overstated. This process has allowed the identification of patients with time-sensitive conditions that may have been missed with traditional triage methods.”

they performed medical screening exams (MSEs) for patients awaiting beds. Efforts were made to preserve resident education by limiting nontime-sensitive imaging during initial evaluations.

The following year, the emergency department (ED) partially opened a new, state-of-the-art facility. This phased opening allowed for early adjustments to address anticipated boarding challenges. The design incorporated triage rooms, workspaces, and internal waiting areas to support a 24/7 Provider in Triage (PIT) model.

While awaiting the completion of the full facility, specifically the fasttrack pod, the department trialed a hybrid PIT staffing model. This model combined advanced practice providers (APPs) and faculty members to try to optimize patient flow through the PIT process. Faculty were tasked with conducting medical screening exams (MSEs) alongside APPs and managing fast-track patients with residents. However, were pulled in too many directions for the hybrid model to function effectively within the interim fast-track space.

When the fast-track pod became

operational during the final phase of the ED opening, the department transitioned to a PIT model fully staffed by APPs, with double coverage scheduled from 10 a.m. to 1 a.m. The redesigned space enabled staff to efficiently screen patients, administer therapeutics, facilitate patient movement, and discharge patients without occupying an ED room. Additionally, the PIT process empowered APPs to utilize resuscitation bays for patients needing a room immediately and

“The Provider in Triage process empowered advanced bays for patients needing a room immediately and ensured were appropriately prioritized, significantly advancing

continued from Page 17

ensure those requiring the next available room were appropriately prioritized. This approach significantly advanced the department's mission of enhancing patient safety and care efficiency.

In November 2022, WCH initiated a similar PIT model aimed at improving the safety of patients waiting in the lobby. The existing triage space was adapted to allow providers to perform MSEs and initiate work-ups more efficiently, prioritizing the sickest patients and those with time-sensitive conditions.

Compared to UCMC, WCH experiences a lower burden of boarding; thus, one challenge at WCH was creating a dynamic PIT model that could be activated during periods of boarding and deactivated when boarding was less prevalent. This approach ensured that resources were allocated appropriately to areas of greatest need.

To accomplish this, activation criteria were established, including a composite of the number of patients in the lobby and the number of patients “to be admitted.” When activation criteria were met, the PIT team was assembled. The PIT team and their responsibilities are as follows:

• Triage Nurse: Conducts triage questions, takes vitals, and orders protocol labs and electrocardiograms based on the complaint.

• Medic (when available): Starts IVs and collects protocol labs.

• Provider (usually an APP): Performs

MSEs, orders additional labs or imaging, and administers preapproved therapeutics.

• PIT Nurse: Collects labs, administers medications, coordinates patient movement through the triage process, and cleans PIT rooms between patients.

• Lead Nurse: Pulls patients into PIT rooms, collects additional labs as needed, repeats vital signs on lobby patients every two hours, discharges patients from triage as appropriate, and rooms patients in ED beds once available.

When activation criteria are met, two patient rooms near the front of the ED are repurposed as PIT rooms. In these rooms, the PIT provider can perform MSEs, order additional diagnostics and therapeutics, and identify patients who need a room immediately or who may be suitable for discharge once their work-up is complete. A second triage area and a family consult room are designated as "discharge rooms," where attending physicians can evaluate low-risk patients from the lobby who have completed their workups and decide whether to discharge them or order additional diagnostics.

If a patient leaves before an MSE, they are classified as Left Without Being Seen (LWBS). If the patient leaves after an MSE but before being roomed, they are classified as Left Before Treatment Complete (LBTC). The combined total of LWBS and LBTC patients is referred to as the Walkout Rate.

When the PIT model was implemented in August 2022, the LWBS/Walkout rate was 10% at both UCMC and WCH, with the goal of reducing it to 3%. As of November 2024, UCMC's LWBS rate has

advanced practice providers to utilize resuscitation

those requiring the next available room

dropped to 3.92%, and WCH’s rate has improved to 2.9%. Walkout rates have been more difficult to change, with UCMC showing stable rates that are trending downward and WCH improving to 4%. As part of the safety mission, both UCMC and WCH review the cases of all LBTC patients, call back any patients with critical or significantly abnormal results, and document the discussion. At UCMC, LBTC cases from the previous 24 hours are reviewed by the Medical Direction Team, while WCH uses the morning shift APP to conduct this review. Between August 2022 and November 2024, follow-up calls were made to 518 patients from the UCMC and 133 patients from WCH. These patients had critical or significantly abnormal test results that might otherwise have gone unaddressed. The value of having more patients seen by a provider, even if they leave before treatment completion, cannot be overstated. This process has allowed the identification of patients with time-sensitive conditions that may have been missed with traditional triage methods. Additionally, patients who see a provider in triage not only tend to wait longer in the lobby before walking out but are more likely to complete their visits. While efforts to optimize the PIT process continue, its impact on improving patient safety, morbidity, and mortality is a crucial to the mission of providing timely and appropriate care to all patients presenting to the emergency departments.

Dr. Thompson is an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Cincinnati and serves as the medical director at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

Dr. Summers is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the University of Cincinnati and serves as the associate medical director at the University of Cincinnati West Chester Hospital.

By Nathan Sandalow, MD; Cole Ettingoff, MPH; Dana Im MD, MPhil, MPP; and Michael Wilson, MD, PhD on behalf of the SAEM Behavioral and Psychological Interest Group

An educator is working with a medical student during his first clinical shift when a call comes over the radio: “We’re coming to you with a 15-year-old male… self-inflicted gunshot wound… bradycardic, hypotensive.” On arrival, brain matter is visible from a wound near the ear. As a dedicated educator, you demonstrate how to assess for brain death and pupil reactivity. The student asks clinical questions and shows great interest. Later, you notice the student staring at the spot where the teen was pronounced dead. Emotionally, he turns to you

and asks, “What do I do now? How am I going to sleep tonight?” How would you respond?

Clinicians expect to face difficult moments and are responsible not only for their own emotional wellbeing but also for the well-being of their patients. As educators, there is an added responsibility to help learners process their reactions to stressful events. Students, many of whom have never experienced traumatic scenarios, are particularly vulnerable. The reactions of those around them can significantly impact how they incorporate the experience and shape their approach

to future trauma. Educators have the opportunity — and the responsibility — to intervene early, setting students on a path toward resilience in a highstress career.

Students are aware that they are being evaluated and may modify their reactions to impress their evaluators. Therefore, it is essential to remain sensitive to subtle signs of distress. This article reviews strategies for addressing these issues.

While students may anticipate witnessing disturbing events, it is crucial to acknowledge this

“Students are at high risk of psychological distress and are least well-trained for coping with these stressors.”

possibility during orientation.

Reassuring students that long-term psychological effects are unlikely can help prepare them. Good educators adjust their level of supervision based on students’ technical abilities, but similar sensitivity should be applied to students' life experiences. This ensures they feel comfortable sharing when an event causes distress. Trauma-informed care recognizes that each person may be affected by different exposures. Educators should avoid appearing judgmental if a seemingly benign event triggers strong feelings in a student.

Orientation materials should include information on self-care, such as encouraging physical exercise and proper sleep hygiene, especially for overnight shifts. Students should be reminded that cold, dark environments should be arranged after overnight shifts to help facilitate rest. Proactive self-care practices — such as sleep hygiene, diet, and exercise — are essential for recovery.

Point-of-Care Strategies

Most trauma survivors experience good psychological recovery. The primary way that attendings can help students is by taking care of their own emotional needs while remaining present for those around them. A wide range of normal reactions exist, and none are inherently inappropriate. A study of student experiences with death found that while students often believe crying is unacceptable, they appreciate the opportunity to share a tear with attendings (Pessagno et al). Grounding techniques, such as box-breathing, should be taught and demonstrated for students. If students become extremely distressed and unable to continue, offer them a break from clinical duties. Students are rarely critical to the team and should

be allowed time for self-care when possible. A brief walk, preferably outdoors, can help.

Humor can strengthen camaraderie and ease tensions, but it must be used sensitively. What may be acceptable among colleagues could offend patients, families, or others outside the group (Watson). Students, undergoing the process of initiation, may struggle to distinguish between appropriate and offensive humor. They may also laugh to ingratiate themselves with others, even if they are uncomfortable. To avoid inappropriate humor, it is best to refrain from making jokes. However, humor is a natural human response

to tragic events; after all, we are humans before we are clinicians. Jokes that mock or poke fun of others are never acceptable, and overuse of humor may indicate poor emotional processing, even if individual jokes seem appropriate.

A sense of helplessness is a significant risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Students, being the least trained members of the team, are at the highest risk (d’Ettorre et al). Giving students specific tasks, such as practicing relevant procedures or

from Page 21

learning an algorithm, will help them find meaning in the event and incorporate it productively. Highlighting the importance of simple tasks, such as assisting with equipment or applying pressure to a wound, can help mitigate feelings of helplessness.

Schools should refer traumatized students to counseling and peer groups when necessary. Social isolation is a known risk factor for adverse outcomes. Clinical rotations can feel isolating compared to preclinical years, so incorporating time for students to socialize and discuss cases — even if not specifically about psychological trauma — can be therapeutic.

Psychological first aid (PFA) encourages minimal disruption to usual routines. Students experiencing traumatic events should be encouraged to continue hobbies and exercise, though this may be difficult due to the demands of emergency medicine (EM). Absence policies should reflect this reality, allowing for recovery time following traumatic events. A brief period for self-care should include connecting with friends and family, as well as rest and relaxation.

Simulation can help prepare students for challenging events without direct patient risk. However, using simulation to expose students to death is not recommended, as it can cause unnecessary distress without providing substantial benefit. Ethical arguments against creating distress in students are strong, especially for those not pursuing a career in direct patient care.

Universal psychological debriefing has been studied and found to be potentially harmful. The proposed mechanism is that such counseling can overly consolidate a mildly

disturbing memory, increasing the risk of PTSD. Psychological debriefing should not be confused with debriefing to improve team performance, which should include directing distressed participants to available resources. According to the World Health Organization, psychological debriefing should be replaced by PFA, which specifically cautions against forcing individuals to talk about their feelings if they do not wish to.

Emergency personnel are at higher risk for alcohol and drug abuse, and tragic events can trigger substance use. Students may also be inclined to use drugs or alcohol but may not disclose this to their evaluators. While alcohol and benzodiazepines can temporarily blunt emotions, they prevent proper emotional processing. Students should be cautioned against relying on these substances as coping mechanisms.

Medications for PTSD Prevention

Some promising evidence suggests that controlled use of steroids, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), intranasal oxytocin, and betablockers could help prevent PTSD in high-risk individuals (Frijling et al). While these medications are not yet approved for clinical use, there may be a future role for psychological "postexposure prophylaxis" in individuals exposed to traumatic events.

Stressful events are a natural part of emergency medicine, and students are particularly vulnerable to psychological distress. As clinicians and educators, it is our role to guide students through these challenges, promoting long-term career longevity and emotional resilience. Orientation materials should introduce students to self-care strategies, and educators should help students find meaningful ways to contribute to the team while remaining sensitive to their emotional needs. After a traumatic event, students should be encouraged to maintain their routines, with adjustments to their clinical schedules if necessary. Social connections should be promoted, while isolation

and numbing behaviors should be discouraged.

To answer the student's question: “While it’s natural for you to have difficulty sleeping tonight, it is unlikely that you will experience long-term psychological effects. If you can find meaning in this case, it may become an opportunity for emotional and professional growth. I suggest you read about suicide prevention or brain injury to prepare for future cases. You could also contribute by writing an article for SAEM Pulse on strategies for dealing with stressful events. Do not perseverate. If you find it difficult to take your mind off the event, try taking a walk outdoors, playing a game with friends, or exercising. Let’s check in soon to see how you are doing. If you are still having trouble, I can refer you for counseling.” (Note: No students were harmed in the writing of this paper.)

Dr. Sandalow is an associate professor of emergency medicine at Chicago Medical School and an attending physician at Advocate South Suburban Hospital. His professional focus is on innovations in medical student education and curricular development.

Cole Ettingoff is a medical student with an interest in all aspects of emergency medicine, EMS, and public health. He is vice president of the American Association of Public Health Physicians and particularly interested in the unique role emergency medicine plays in the broader healthcare system.

Dr. Im is an attending emergency physician at Mass General Brigham and Harvard Medical School, where she leads quality and safety initiatives across the MGB Emergency Medicine System as the MGB enterprise emergency medicine director of quality and safety.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor in the departments of emergency medicine and psychiatry at the University of Arkansas and serves as the emergency department lead for neurological emergencies, psychiatric emergencies, and substance use disorders.

By Andrew Melendez, DO and Salil Phadnis, MD

As the academic year progresses, fellows across the country may find themselves balancing the excitement of starting their wellearned fellowships with the realities of navigating the job market as future attending physicians. This can be particularly challenging for those in one-year fellowships, where the timeline is short and intersects with other obligations like written board exams. To guide fellows through this process, Dr. Anna Bona from Indiana University School of Medicine and Dr. Annemarie Cardell from Emory University recently shared their insights during a Simulation Academy Early Career

Subcommittee session. Their discussion highlighted a significant gap in graduate medical education: while many residency programs offer a "life after residency" component in their curriculum, the nuances of seeking employment after fellowship are often left to mentorship and trialand-error experiences.

The panelists focused on four key topics, which are outlined below.

A crucial first step in this process is self-reflection on career aspirations. Fellows should consider asking themselves:

• What proportion of my time do I want to allocate to simulation vs. clinical practice?

• Is there a particular group of learners I want to work with?

• Is interprofessional simulation a priority for me?

• Do I want to focus on quality and safety initiatives?

• Am I interested in collaborations, such as EMS education partnerships?

• Do I anticipate my simulation career following an administrative path (e.g., simulation center director) or a medical education path (e.g.,

“The transition from fellowship to a faculty position is an exciting yet challenging culmination of years of dedicated training.”

graduate medical education core faculty)?

• Is simulation research a key interest, and do I anticipate needing support with funding and grant writing?

Discussing the answers to these questions with a fellowship mentor can help fellows narrow down a list of institutions to target.

Early engagement with key personnel such as simulation directors, residency program directors, and department chairs is highly recommended. Fellows should reach out to mentors from their residency and fellowship programs to connect with faculty at institutions of interest. Keep your curriculum vitae (CV) updated throughout your fellowship year so it is readily available for a "warm introduction." These connections and the conversations that follow can clarify expectations for prospective faculty positions, uncover unanticipated opportunities, and potentially even lead to interviews before positions are publicly posted.

Fellows should not underestimate the freedom of choosing their own location post-fellowship. This is an opportunity to take newly developed skills to the place that best aligns with personal and professional goals. Unlike previous moves dictated by medical school acceptances and the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) algorithm, fellows now have control over their location.

Considerations for fellows include:

• The moderate benefit of remaining at their current institution or returning to their residency training site, as the familiar environment may ease the transition to a faculty role.

• Personal and family preferences, especially after years of limited choices during training.

• Regional variations in job offerings and compensation.

Gaining an understanding of regional norms for compensation and benefits during the negotiation phase is new for most fellows. It is rare to accept a job offer without negotiating in some way. Fellows can ask local mentors and seek connections with junior faculty in the target city to clarify local norms. This knowledge helps ensure fellows are not undervalued. City-specific advice is often shared by mentors from a fellow’s residency or fellowship program who have experience helping trainees negotiate contracts.

The transition from fellowship to faculty position is an exciting yet challenging culmination of years of dedicated training. Although the process may seem overwhelming, taking time to reflect on career goals, seeking mentorship, and making meaningful connections can lead to

valuable opportunities. Choosing a location that aligns with both personal and professional priorities adds another layer of fulfillment. Finally, embracing the negotiation process allows fellows to start their new roles with confidence and clarity. With preparation and mentorship, fellows can turn this pivotal moment into the foundation for a successful career.

Dr. Melendez is a medical simulation fellow at Yale Center for Healthcare Simulation and an instructor of emergency medicine at Yale School of Medicine. He earned his medical degree from Touro University California and completed his residency in emergency medicine at the University of Connecticut.

Dr. Phadnis is a medical simulation fellow at Indiana University. He earned his medical degree at the University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine and completed his residency in emergency medicine at Florida Atlantic University Schmidt College of Medicine. X: @salphadnis

By Matthew C. Johnson, MD and Luke Duncan, MD

The placement of central venous catheters (CVCs) has significantly advanced over the past few decades with the development of ultrasound guidance and the Seldinger technique. A common indication for CVC placement is poor intravenous (IV) access in hypovolemic or vasodilated patients requiring volume resuscitation, vasoactive medications, or venous access. Studies have linked the diameter of the internal jugular vein to central venous pressure, demonstrating that during episodes

“Research has shown that passive leg raises can increase the diameter of the internal jugular vein, potentially facilitating successful cannulation.”

of vasodilation or hypovolemia, the internal jugular vein often becomes small and easily compressible, which

can make cannulation challenging. To enhance vessel size and improve success rates, patients are typically

positioned in the Trendelenburg position.

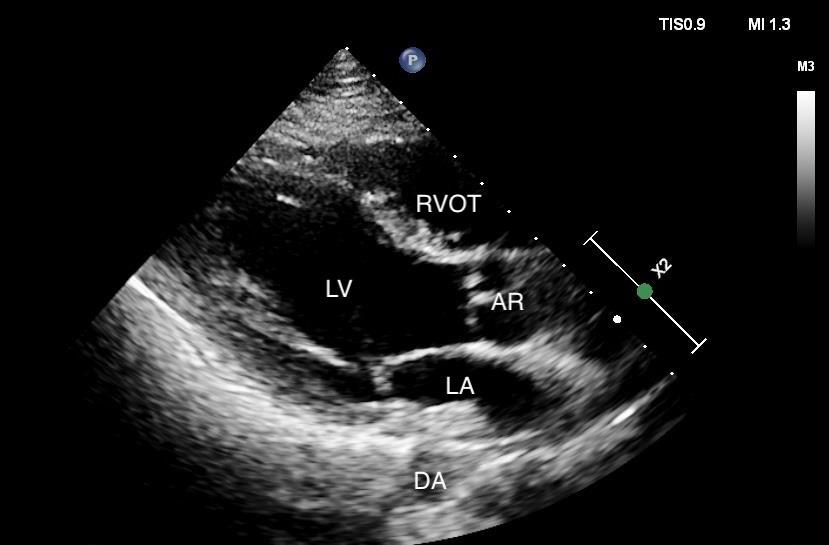

Research has shown that passive leg raises can increase the diameter of the internal jugular vein. It follows that an increased vessel size may facilitate cannulation; however, this technique has not been widely explored as an adjunct for placing internal jugular CVCs.

In the case covered in this article, an 85-year-old man with septic shock caused by a perforated sigmoid colon was profoundly hypovolemic and required crystalloid resuscitation and dual vasopressors. Ultrasound revealed that his internal jugular vessels were completely collapsible. Initial attempts to place the catheter were unsuccessful due to vessel collapse. The Trendelenburg position did not adequately dilate the internal jugular vein, as shown in Image 1. However, using a passive leg raise, significant dilation of the internal jugular vein was observed, enabling successful cannulation (Image 2).

Although the leg raise in this case was performed manually, using a hospital bed to elevate the legs could achieve similar results. This technique may prove useful in assisting with CVC placement in patients experiencing hypovolemic or vasodilatory shock with compressible vasculature. Further consideration and study of this approach may be warranted.

Dr. Johnson is a surgical critical care fellow in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Albany Medical Center.

Dr. Duncan is an associate professor of emergency medicine and surgical critical care. He is the assistant program director of the resuscitation and emergency critical care fellowship, medical director of extracorporeal life support services, and division chief of critical care in the Department of Emergency Medicine.

By Corlin Jewell, MD; Dana Loke, MD; Stephannie Acha-Morfaw, MD; and Abraham Alseryani

Early clinical exposure to emergency medicine is uncommon for medical students, who often focus on research during the summer of their first year. These research opportunities frequently lack mentorship and hands-on clinical experience. To address this gap, the University of Wisconsin* developed the Emergency Medicine Summer Immersion Program. This initiative provides rising second-year medical students with practical experience and a comprehensive understanding of emergency medicine. The program offers insights into the operations of emergency departments and prehospital agencies, with an emphasis on recruiting students from

disadvantaged backgrounds who are interested in serving historically marginalized communities.

A significant lack of representation persists among emergency medicine physicians from underrepresented groups. In 2020, only 28% of clinically active emergency medicine physicians identified as women, 9.2% as Hispanic or Latino, 4.9% as Black or African American, and 0.1% as American Indian or Alaska Native Additionally, a 2022 study of 37,485 medical students revealed that 17% identified as underrepresented in medicine (URiM), and among these, 23.9% were from low-income backgrounds.

The definition of URiM has expanded to include individuals who contribute diverse intellectual and cultural perspectives due to life experiences such as overcoming adversity, financial hardship, or being first-generation college students. Programs like the Summer Immersion Program aim to address these barriers by fostering mentorship, building community, and providing support. These efforts can enhance graduate medical education (GME) placement and contribute to a more diverse emergency medicine workforce.

The program’s inaugural participant, Abraham Alseryani, joined the immersion from May to June 2024.

“This environment provided me with a profound understanding of modern emergency medicine and the critical role of emergency department providers.”

A first-generation college graduate and medical student with a multicultural background spanning Mexico to Jordan, Alseryani exemplifies the program’s mission. Reflecting on his experience, he shared:

“The majority of patients I encountered had complex, highacuity medical issues. Some faced acute crises complicated by chronic conditions, while others sought care in the emergency department due to a lack of alternative options. This environment provided me with a profound understanding of modern emergency medicine and the critical role of emergency department providers.

“The program included handson clinical skill sessions where I learned suturing techniques and the basics of point-of-care cardiac ultrasounds. I also assisted with fracture reductions and casting under the guidance of orthopedics residents and learned to work closely with consultants. These practical skills will be invaluable as

I develop my professional identity as a physician.

“However, the highlight was shadowing various emergency medicine physicians. Observing different approaches to handling difficult situations and delivering bad news offered insights that cannot be taught in a classroom. Despite their varying personalities and methods, all the physicians shared a commitment to treating every patient regardless of socioeconomic status — a principle deeply resonant with me, given my own experiences with inadequate health care access. This dedication has strengthened my resolve to pursue emergency medicine.

“Overall, the program was an invaluable learning opportunity that deepened my passion for the field. I strongly recommend it to students considering emergency medicine. It provides a clear understanding of the specialty and the chance to engage with a community of dedicated healthcare professionals.”

Alseryani aspires to become an emergency medicine physician serving underserved populations. Hopefully, the Summer Immersion Program will continue to attract students like him, enhancing the diversity of the emergency medicine workforce and inspiring future leaders in the field.

*The Emergency Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a Level 1 trauma center, serves adults, pediatric patients, and as a regional burn center. In 2023, it treated more than 70,000 patients.

Dr. Jewell is director of the Medical Student Education Fellowship, partner in longitudinal teacher coaching, and an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. She leads the medical student clerkship team for emergency medicine.

Dr. Loke is assistant director of medical student education, quality lead for the Veterans Hospital Emergency Department, and resident education partner in longitudinal teacher coaching. She is also an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Dr. Acha-Morfaw is assistant director of medical student education, chair of the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee in the Department of Emergency Medicine, and assistant block leader for acute care at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. She is also an assistant professor of emergency medicine.

By Jason Rotoli, MD; Luke M. Johnson MD; Richard W. Sapp, MD; and Wendy C. Coates, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine Accommodations Committee

In the fast-paced environment of the emergency department (ED), effective communication with patients is essential to deliver equitable care. With nearly 1 in 4 Americans having a disability, health care providers must accommodate a wide range of abilities and communication needs. The Americans with Disabilities Act (Titles II and III) requires institutions to provide necessary accommodations for individuals with disabilities.

While some patients may use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices, others may need additional accommodations for full communication access. Similar to foreign language interpretation, relying on family members or companions for communication should be avoided unless they are specifically trained for this purpose, as doing so may unintentionally alter critical information. In emergencies, however, any available means of communication may be necessary.

This article highlights several applications that can enhance communication between emergency providers and patients requiring accommodations. Although many of these tools may be compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), it is recommended that all communication applications be used on HIPAA-compliant devices to protect patient privacy. The following examples are designed and/or endorsed by individuals with disabilities.

The DHH community encompasses a wide range of identities and communication preferences. For instance, some individuals use American Sign Language (ASL) and identify as culturally Deaf, while others identify as deaf or hard of hearing (HoH) and may rely on a combination of spoken language, written language,

BigText*

Live Transcribe*

Voice4u TTS

lip reading, or sign language. Given these varied preferences, no single communication method works for everyone, and emergency providers should familiarize themselves with multiple options.

For patients who use ASL, a qualified in-person ASL interpreter is generally preferred. When unavailable, virtual

remote interpreting (VRI) may be an alternative, though it has limitations such as reliance on internet speed, screen clarity, and positioning challenges. For those who prefer spoken or written language, several applications can facilitate communication, the following table provides some viable options.

Live Transcription — Turns spoken words into written text on your device with good contrast and the ability to change the size of your font.

Live Transcription —Turns spoken words into written text on your device with the ability to change the size of your font. Apple

Live Transcription — Reads what you type in your choice of naturalsounding voices. The app can read words from a photograph with optical character recognition (ORC) technology. Apple

* Denotes a free application

“Critical materials such as hospital forms, medical records, and discharge instructions are rarely provided in accessible electronic formats that enable the use of adaptive voiceover software.”

Approximately 10% of noninstitutionalized U.S. adults report a speech, language, or voice disability. These individuals face significant health care disparities, including lower access to technology that could address communication barriers. Experts

Voice4u

Proloquo2Go

estimate that 5 million Americans could benefit from AAC to enhance communication.

AAC tools, including picture communication boards, speechgenerating devices, and app-based technologies, can bridge these

gaps. They are particularly useful for individuals with intellectual disabilities (e.g., Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome), neurodevelopmental disabilities (e.g., autism spectrum disorder), and motor disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy).

Picture/symbol-based technology to generate verbal communication. Android; Apple

Picture/symbol-based technology to generate verbal communication. Apple

Speak For Yourself * Picture/symbol-based technology to generate verbal communication. Apple

Leeloo*

Picture/symbol-based technology to generate verbal communication with text-to-speech voice capability. Android; Apple

* Denotes a free application continued on Page 33

continued from Page 31

Navigating the health care system can be particularly challenging for individuals who are blind or have low vision due to numerous provider and institutional barriers. Many health

care providers lack the necessary training and awareness to effectively support patients with visual needs. As a result, patients' ability to read and interpret written documents is often overestimated, and appropriate accommodations are frequently overlooked. Critical materials such as hospital forms, medical records,

Voice Dream Reader

and discharge instructions are rarely provided in accessible electronic formats that enable the use of adaptive voiceover software. The table below outlines readily available textto-speech technologies that can assist in making these written materials accessible to patients with visual needs.

Text-to-speech application with screen reader and continuous text highlighting. Apple

Siri* Integrated iPhone text-to-speech application and screen reader technology. Apple

TalkBack* Integrated android text-to-speech application and screen reader technology. Android

Seeing AI*

Speech-to-text and screen reader technology. Apple

* Denotes a free application

Ensuring communication accessibility not only improves bidirectional information exchange, but also fosters inclusion, promotes patient autonomy, and empowers individuals with disabilities. By incorporating these applications into their practice, emergency medicine providers can take meaningful steps toward delivering equitable health care to all patients.

Disclaimer: The applications mentioned in this article are not officially endorsed by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the SAEM Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine (ADIEM) as a whole. This list is not intended to be comprehensive or exhaustive. Furthermore, the authors have no financial affiliations with any of the recommended applications.

“Approximately 10% of noninstitutionalized U.S. adults report a speech, language, or voice disability, yet 5 million Americans could benefit from augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) tools to enhance communication.”

Dr. Rotoli is an attending emergency physician and associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center. He is the associate emergency medicine residency program director and directs the Deaf Health Pathways humanities elective at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. His research focuses on health disparities among marginalized populations, particularly Deaf American Sign Language users. He is fluent in ASL and works with Partners in Deaf Health, a nonprofit organization promoting awareness of the health care needs of culturally Deaf individuals.

Dr. Sapp is a fourth-year resident in the Harvard Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency who is passionate about improving health care for individuals with disabilities through medical education and research on health care disparities.

Dr. Coates is an education scientist who advocates for improved access and quality of care for individuals with disabilities. She is the immediate past president for the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Dr. Johnson is an emergency physician on the medical staffs at Geneva General Hospital and Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hospital.

By Stefanie Sebok-Syer, PhD; Jean Reyes, MBA, MSN, RN; Andrew Stromberg, MD; Cathy Castillo; Julie Craven; Natasha Humphries, MBA; Brent Portman; Ting Pun, PhD; and Saumya Sao

Emergency Medicine (EM) physicians specialize in providing care for unscheduled and undifferentiated patients of all ages. The emergency department (ED) is often seen as the U.S. health care system’s safety net — “the one place in the U.S. health care system where care is guaranteed, and for some patients, emergency care is the only medical treatment they receive.” Central to this role of advocating for patients,