6 minute read

First Port Of Call

Ahead of a tasting event with Sandeman in November, we explore the history of port and find out why the Club’s Head Sommelier recommends we broaden our often seasonal palate.

Words by Timothy Barber Photography by Jamie Lau

Advertisement

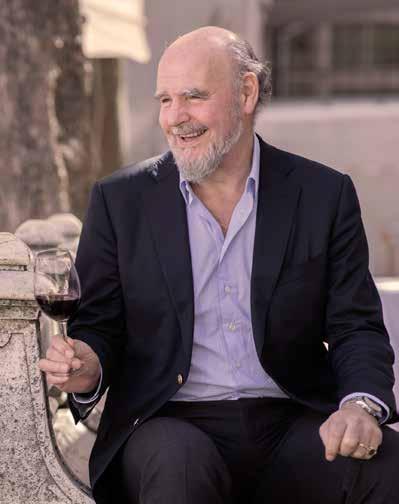

SUCH ARE THE well-ordered lead times for Pell-Mell & Woodcote that I find myself writing about port, something I’ve nearly always consumed in a state of cheesefortified merriment in November and December, at the height of the August heatwave. I may as well be talking about mulled wine and mince pies while sipping daquiri sun-downers. But Yves Desmaris (right), the Club’s Head Sommelier, assures me that in my seasonal bias I’m not alone. He says you’ll see barely any port decanted in the Great Gallery during the spring and summer months, while of course it flows in ever greater quantities as Christmas approaches, matched by the lorry-loads of Stilton it invariably accompanies, and no doubt the excuses bountifully wheeled out the next morning (since blaming port for the effects of the epicurean excesses that precede it is a tradition as time-honoured as passing the decanter to the left).

Traditions are there to be observed and enjoyed; and indeed, port’s sweet, mellow richness – whether delivered in the luxurious intensity of a vintage ruby, or the caramel beauty of an aged tawny – really does make it a wonderfully hearty way to close out a blow-out. But is it possible that the limited, habitual nature of our port consumption can leave us blunted to its variety and complexities?

Yves, whose current recommendations from the Club cellar include the velvety greatness of Taylor’s 1985 vintage, now truly coming into its own, and Graham’s single vineyard Quinta dos Malvados from 2004,

Above: George Sandeman avows that this may be so. “I think people don’t always know how much choice there is, and how much variation you can find between different styles and ages,” he says. “Even if you’re just having it with cheese, the way different ports work with different cheeses can be a lot more intense and nuanced than people often realise.”

Maybe, though, the later into a meal one gets, the less sensitivity for nuance one tends to muster; at least Club members can rely on Yves to make a spot-on selection either way.

George Sandeman, the eighth-generation scion of one of the industry’s most celebrated shipping dynasties and marques, notes that port’s positioning at the back of both the meal and the year is at least better than the days when it was being downed in pubs in brim-full schooners as an alternative to undrinkable French wine. Nevertheless, for those tantalised by the true breadth of the fortified wines made in Portugal’s Douro Valley, Sandeman is on a mission to reveal their mysteries – as he’ll be doing at Pall Mall on 28 November.

“I’m a great believer in showing people the diversity – there are other cheeses than Stilton, and other ports than vintage,” he enthuses. “At the moment, more and more young producers are coming in, making their own styles and interpretations. As a region, the Douro Valley has an enormous diversity of terroir and microclimates, meaning you get huge variations that are very much influenced by the region. It’s a world to discover.”

Sandeman points out that in other countries port is drunk differently. The French like to chill it and enjoy it as a sweet aperitif; in Portugal itself it can be both aperitif and dessert wine, also chilled (in particular, Sandeman recommends experimenting with white port as an alternative to the likes of sweet dessert staples like Sauternes or Tokaji); in America, where traditions weigh lightly, anything goes (I remember being served marvellously refreshing port & tonics in a rooftop bar in Manhattan, not that you’d probably want to try that with anything significantly aged or cherished).

But it is, of course, British character and entrepreneurialism that stamped itself

across the Douro region centuries ago and gave us port as we know it, as the names of so many of its most famous marques – Sandeman, Graham’s, Taylor’s, Cockburn’s, Warre’s – attest. In the 17th century, fuelled by a boycott of French wine during the Anglo-French wars, British importers turned towards the wines of their ancient trading partner, Portugal, and in particular those from the country’s northern Douro region, exported via the coastal city of Porto, giving the wine its name. Here, a brandylike spirit known as aguardente began to be added during the cask fermentation process, ostensibly to help preserve the wine for maritime export. This created a fortified wine that was sweeter, stronger, and with a higher alcohol content. The British discovered a taste for it, and so established an industry, and a cultural exchange, that is today worth around €800 million annually, and rising.

To the newcomer, though, port, with all its categories and sub-categories, can be a daunting and even contradictory subject to explore. There is the classic ruby port, blended from wines of various ages and origins into a given house style; the everpopular tawny, made from wines aged in barrels for years or decades, giving it its mahogany colour and deep, complex flavour profiles; vintage port, declared only a few times each decade and delivering prestige bottlings that keep developing for decades more; and LBV (late bottled vintage), a somewhat more affordable alternative to vintage, made from high quality wine of a single year that’s barrel-aged for four to six years before bottling.

Those are the headliners, but connoisseurs will know that a host of further styles – rosé, white, colheita, crusted, garrafeira, single quinta vintage – awaits those prepared to put the stilton to one side and let the wine do the talking.

Which simply leaves the question of how to serve it. Decanting is never a bad decision: for ports that have spent a long time in the bottle, it helps to separate out the sediment, while older ports in particular benefit from the aeration, especially if served at the correct temperature. And on this point, Sandeman is emphatic: chilling really is best. “I like to put my ruby ports in the cold for an hour or more before serving, and the tawnies I enjoy well chilled. The advantage is that it reduces the volatility of the alcohol, allowing inherent aromas to come through and be enjoyed. If it’s too cold, you can warm it by cradling the glass in your hand for a couple of minutes.”

Ah, the final element: the glass. Plenty of members will no doubt have encountered (and may still be harbouring) the small liqueur glasses once considered the norm; if so, it’s best to leave them to one side. “Since 2001 the evolution of wine glasses has been massive, and today we recommend that a medium size white wine glass can be ideal. Of course, it’s important to get the dose correct, and normally a serving of 5-6cl is sufficient. In this way, one can swirl and observe the colour and intensity, and inhale the aroma creating anticipation for the flavours which follow.”

Please visit the Club website for further information about the tasting event with George Sandeman on 28 November.