4 minute read

Future Proof

The future is now

A Club member and a multi award-winning proponent of future technologies, Professor Yvonne Rogers, who this year was elected as a fellow of the Royal Society, is at the forefront of advancements in artificial intelligence.

Advertisement

Words by Peter Jenkinson and Annabel Harrison Photography by Martin Burton

AS FAR AS job titles go, ‘Professor of Interaction Design’ is one that, for most of us, probably requires some explanation. So here we go: ‘Interaction Design’ refers to ensuring that digital products, systems and services meet the needs of their users. In other words, the design of technology that can enhance our lives.

In addition to holding the post of Professor of Interaction Design at UCL since 2011, Yvonne Rogers is also a Director of UCLIC (University College London Interaction Centre), Deputy Head of the Computer Science department at UCL, and one of the authors of the definitive textbook on human-computer interaction, which has sold more than 300,000 copies worldwide. Who better, then, to ask about current progress on ‘human-centred AI’?

When she’s not pioneering future technologies, Professor Yvonne Rogers can be found at Pall Mall, where she is a member of both the Bridge and Photography Groups and a regular user of the pool. When we met, in the clubhouse of the Royal Automobile Club, what subject could we start with other than the impact of AI on the motoring world?

Self-driving and autonomous behaviour in cars are two developments which have been making headlines of late. The talk is usually about how we might remove the driver, but Yvonne’s approach is different. “We should be looking at how we can enhance the driving experience; how can we augment it,” she argues. “Of course, we’ve had parking assistance for a while, but it could be greatly improved, and we’ve enjoyed having our windscreen wipers automatically deploy when rain starts – but what about driver and passenger comfort?” As examples, she suggests sensors in seats which automatically adjust for comfort (detecting if you haven’t moved for a while and managing the seat position), changing the climate control in the car if it detects it is has become too stuffy, playing music appropriate to your mood or providing route guides to explain where you are passing through.

Left: Professor Yvonne Rogers

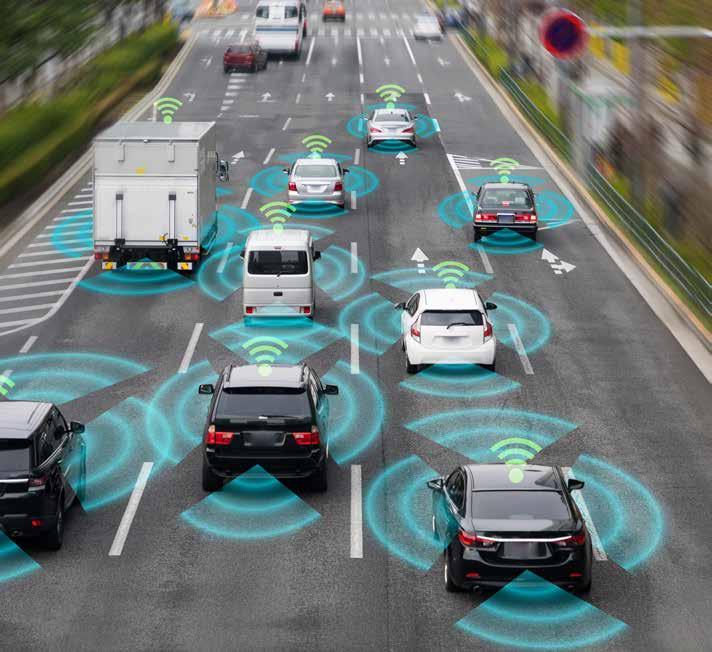

Above: AI can help identify hazards on the road

There’s so much more that AI can do to improve car safety too: “There’s a lot that can be done on hazard identification – alerting drivers to other road users and knowing the difference between those and static objects, for example. Technological advancement in this area is moving on apace. Displaying driving information on heads-up, on-windscreen displays rather than looking down at oversized tablets is another technology that is better suited to the needs of the driver and one I’m a real advocate of.”

Healthcare is another area where there is enormous potential for AI to make a difference, including helping doctors to diagnose from a distance with much more accuracy than they can currently. “Presently, we have wearables that can assist with diagnosis but we can take this much further. For example, there is an app called SkinVision which can be downloaded by anyone, who can then take a photo with their smartphone of a blemish on their

skin to check whether it is a lesion. The app compares the photo with millions of images on its AI database to assist with the diagnosis. There is also new camera technology where a patient can swallow a miniature capsule which will send two images per second of your intestine to a computer, alleviating the need for an endoscopy. It is much easier to administer, less uncomfortable and considerably cheaper. Initiatives like these,” says Yvonne, “will both help make health services more efficient and provide a better experience for patients.”

Anyone who has suffered a delay reconnecting with their luggage in an airport this summer will be pleased to hear that there is lots of scope for AI to help there as well. “It could be deployed to identify our suitcases more effectively and lead us to them (or them to us) – saving hassle, time and money. There’s also a trial at Heathrow of a system which can rapidly scan 250,000 bags a day for animals or animal products to combat illegal wildlife trafficking.”

Other applications for AI include facial recognition for crime prevention or investigation: a huge move on from blurry CCTV images. In retail environments shoppers could use AI to guide them to their preferred products using analysis of what they’d bought or browsed previously – an example of augmenting the shopping experience. AI can also help people make their selection when there is a myriad of choices. For example, instead of having to agonise over what to make for a dinner party, an AI-enabled personal assistant can help you decide based upon a combination of your guests’ dietary requirements, what is seasonal and what you like to cook. AI technologies are opening up new possibilities in many sectors apart from transport, healthcare, shopping and security. “The advances could be transformative in many areas of our lives,” concludes Yvonne, “as long as we focus on how people will benefit and how it can empower them as well as on the technology in itself.”

Above: New camera technology where a patient can swallow a miniature capsule

Below: AI could be deployed to identify suitcases more effectively