The Lavender

Wesleyan’s Prose, Poetry, and Art Magazine

Spring 2023

route9.org • @route9wes

About Us

The Lavender is Wesleyan’s student-run poetry and prose literary magazine that publishes twice a semester. The literary magazine is run under the Route 9 Literary Collective which also publishes chapbooks, social justice pamphlets, and a once-a-year anthology of writing from Wesleyan faculty, staff, students, along with the work of Middletown Residents.

Why Route 9?

Route 9 is the road that connects Middletown to the rest of Connecticut. It is the central artery of movement that every Wesleyan student, faculty, staff, and Middletown resident has driven on. It connects us and moves us forward. Learn more at route9.org!

Special Thanks

to:

The heroes at 49 Home Ave., all the dear friends who make this magazine possible, Zahra Ashe-Simmer, Merve Emre, Amy Bloom, Ryan Launder, Alpha Delta Phi, The Shapiro Writing Center, The Wesleyan English Department, The Green Fund, and the SBC.

The Lavender Team

Editors-in-Chief: Oliver Egger and Immi Shearmur

Managing Editors: Georgia Groome and Ella Spitz

Poetry Editors: Emily Hollander, Jane Hollander and Casey Epstein-Gross

Prose Editor: Maya Scheinfeld

Design Editors: Madeleine Metzger and Spencer Klink

Copy Editor: Emma Goetz

Assistant Poetry Editor: Anna Logan

Assistant Prose Editor: Sylvie Pingeon

Assistant Design Editor: Katia Michals

Senior Editors: Ben Togut, Michaela Poynor-Haas, and Sofia Baluyut.

The Team: Clara Martin, Colin Bloom, Franklin Mindich, Isabella Koz, Jake Gale, Julia Gardner, Liz Pace, Myles Edelson, Nicole Lee, Nomi Kuntz, Sabrina Tian, Sadie Gray, Amanda Ding, Samantha Hager, Sophia Neiblum, Tatiana Wolkowitz, Alexei Brusiloff, Chiara Mapp, Hannah Langer, Eli Hoag, Rory Dolan, Tyler Asher, Ava Guralnick, Lucy Schwalbe, Diana Q. Tran, and Chloe Duncan-Wald

Cover Design: Spencer Klink

Logo Design: Leo Egger

Sweets Sergeant: Maggie McCormick

Dear Reader,

Letter

from the Editors

As always, the theme of this issue is unbelievably vague.

This is what the image “threshold” inspires for us: a wooden door frame painted blue, the door weathered, ajar; just behind that door is a room, the walls lined with windows with scratched panes flooding the room with light; There is a table in the center of the room with a bowl of oranges. You walk inside. You peel. You bite. It is sweet. Two birds wearing tweed jackets sing on the branches just outside.

If such an image from your editors does not appeal to your sensibilities, please feel free to file a complaint with our HR team.

Beyond blue doors and oranges, a threshold represents the beginning of change. It is

the moment, the edge, when the future begins to unfold, the past starts to be laid bare, the story unwinds. Art itself is a threshold, a space where we begin to understand ourselves and others, where we begin to become a more truthful version of ourselves, where we begin to grow.

We want to give a deep thanks to the editorial and design teams who make this magazine possible, the writers and artists for their vulnerability and their amazing work, and of course, most of all, to you, dear reader.

We apologize that the theme of this issue is not “The Divine Feminine.” Perhaps next time.

With love,

Oliver and Immi Editors-in-Chiefand other flowers

Michaela Somersdandelions are innately undesired. my father, a biologist in his carefully plotted garden, told me this as a fact of nature.

he taught me this supposed truth years ago, with gold from the plant’s crushed buds and stems, sincerely gathered from the yard, still bleeding onto my tiny hands. and so, in this way, he would mow the lawn, the pollen painting my face just a reminder of a time before this guilt began to root in me.

it is too simple to admit i am still nothing but that child grown and weathered, nothing but a weed, sprouted in a pavement crack; it may be too naive to assume that to a simpler eye i must look like some sort of flower.

one of these days, i will be picked and tucked behind an ear. how endearing, to find beauty in the weeds. often i must remind myself: there is this staining sort of yellow so too in the sun.

She has a taxidermied rabbit head on the left corner of her shelf & reads Ginsberg splayed out on her dorm room floor.

Saturday we watched Moonlight, intertwined on the skin of her loveseat. I couldn’t unclip her bra & she laughed & I liked the sound so much I kissed her squarely on the mouth. Her breath smelled like cinnamon.

Once, I swore her skin was moonlight. I ran my fingers over the small of her back walking along riverside park & held her tighter when a fruit vendor called us dykes.

The Moon and I Ali Hochfelder

The swirl of the night courses

The air is tv static lapping at my arms

Light traipses across the room in a tango.

When everything begins to slow And Intimacy’s glow has dwindled

The night hums dissonantly

Starving for interpretation.

My lips are an ‘o’ and breath curls out

Like a dog bays at the moon—

But I am not a dog.

The moon is a stranger in the sky

We are languid, floating through space;

The celestial body is craggy and hard

But my body is soft

Only my pink skin protects me

There are no straight lines Or edges along my body.

The old moon hangs over the night

Which courses in a whirling moment of movement.

Blue

Alexei BrusiloffDays were a different shade of blue. An April sky seemed closer to the ground, boxing in the city, distilling the world to my apartment. Compressed images lose their value, forget what they’re supposed to be, replace my responsibilities with clouds and hazy walks down the colors of Second Ave. A timely vacation once form and function were no longer convenient for me, finally able to have my own private definition of the world— one where there’s only one way to describe the sky, where a rainbow doesn’t arch, just speeds along in a straight line, piercing the clouds hanging over a maze of impossible architecture, with a grid running under it, proving at once that it exists and that it shouldn’t.

reshoots

Molly Connolly-Ungar// let me walk you through // the ways in which I am what I make of myself // the obsession // I am carving from years and moments of leisure // the breaths I am taking of café air and unnecessary accents // I am much more clever when spread apart // and I should know better than to see you in // the clasp on a shirt // the sides of a canvas // eluding sound quality like you mean it // before you start to believe // in anything more than that table // this desk // a carpet a series of grasses // would you meet me in a field if I promised // a sketch of the doors I walk past each morning // and stand a moment // watch // for the intersection of wall and stone // six years ago I learned // I am easier to explain than I look // I am grateful to have found this time // I am still caught up in oranges and light sources // I am in the plum scented glassware // the birds you think you’ve seen // waiting // withstanding // and branches taken as they are // and have you seen the way // lines turn together // and were you disappointed // do you think about the shapes cloth makes // the only time I have ever cared about topology // the rises and falls // can you tell how hard I am trying to avoid proper nouns // can you see it in my voice // in the lists I am writing into your head? Issue VII: Threshold

To Do Today and Maybe Always

Isa Lozada- Wakeupwakeupwakeup

- Call your dad back

- Apply to summer internship

- Make some tea and then make some more

- Do the crossword and leave it unfinished

- Learn how to knit a backless dress

- Find the time to knit a dressless back

- Grow cherry tomatoes outside your dorm

- Walk all the way home for a momentary hug

- Churn time slowly forward then back then back again

- Finally figure out how to dance in your dreams and then never stop

- Predict each of your friends futures, place them in boxes to bury and watch the boxes grow into people you don’t know anymore

- Paint your nails light purple

- Figure out how to get closer with your sister

- Figure out how to get your sister closer

- Start hiding from that thing in your chest

- Relearn yourself and then teach it back

- Say goodbye to that never ending feeling

- Tell your mom you miss her but that talking to her makes you miss her more

- Make a time lapse of your life through her eyes without her ever knowing

- Water the plants in your room

- Discover what is always holding you back from that one thing and throw it directly overseas

- Figure out for once where you are going

- Go back to your childhood home and wrap it in your hand for safekeeping

- Figure out what you love

- Figure out you

- Write a story about that time you once lost the moon to a crack in your hands and you searched for it everywhere but it was nowhere to be found so you cried until a new moon was born

- Stop hiding from that thing in your chest

- Light a candle for every time your mind wanders effortlessly

- Find yourself in another life and find something to believe in that isn’t you or anyone else

- Learn to play the guitar finally finally

- Remind your grandmother of what she loves and who you are

- Wakeupwakeupwakeup

Your Wecome

Franklin MindichThe view is to him as an eclipse or a sunset would be to a man. He would sip a beer if he were a man as, on alternating Sundays, he climbs out and takes a look at the earth.

A rat on the blank horizon. Fur matted with moon dust.

“It looks like I’m going gray, Huh?”

One finds that they age faster when ensconced in solitude. Even the solitude of space.

So exciting.

He looks at the earth. He talks to it like he can hear the billions of voices crying out. He speaks softly like he is calming a horse with its legs in the air.

My Father’s Secret Hyacinth Tauriac

Daddy,

Where does it hide?

Is it behind a bitten lip

Cloaked by a tight throat

Subdued by a clenched fist

What does it look like?

How many lines furrow between your brows

How long does your puffiness last

How far does the snot dribble down your chin

When does it come?

How funny must the joke be

How close the loved one lost

How deep the wide wound

Daddy, tell me just Tell me.

Do you ever cry?

Maybe

When I was born and came out still raw

No sound

Mom bleeding

Eyes rolled back white as the Heavens she glimpsed that day

Maybe

When you put me on the bus for the first time

Watching me be dragged into the world to become an Other

Your brown baby now a Black Girl

Maybe

It was that fight we had You demanding to know whose White hands had printed my skin blue Me telling you to fuck off Lines crossed

Door slammed

Daddy, Were you on the other side?

Did your defeated weight lean against the wood

Like me

Did your heavy head peel down to hang

Like mine

And if I had opened that door

Would I have finally understood

Why my forehead prunes

Why my puffy eyes take days to fade

Why my snot soaks my collar

Why they say

You have your Father’s eyes

No, Your secret remained shut.

But maybe You’ve been crying all this time and your sobs ring out as a sound I am too afraid know at a decibel

I’ve thought best not to hear

When a Black Father cries tell me, Daddy

What happens if I see your tears?

Driving With My Eyes Closed

Sophie JagerI can drive the roads of my hometown with my eyes closed. My front door is seven minutes and forty-six seconds from school. Six minutes from the grocery store. Eleven minutes and twenty seconds from the access road to the mountain. My fingertips on the wheel know the angle to turn at every intersection; my foot on the brake knows where the pavement is prone to potholes. A quick left after the gas station will take you to Sammy’s, although the sign out front calls it The Wood Fired Pizza Company for tourists who never looked Sam in the eye or donated to fund his chemotherapy. Hannah and Quinn used to work there, smoking together out back under the pretense of chopping wood for the pizza oven. A right will take you through the golf courses, which are good for sledding if you sneak in behind the condos once the Second-Homers have returned to New York or Miami or Montclair. I know when I’m on Main Street because the buildings are huddled up close together to stay warm, casting the sidewalks in perpetual shadow. I’ve hit Route 30 when the wind lifts my hair up and tosses it over my shoulders, sweeping across the Battenkill River and through the open driver’s side window.

Sometimes I like to imagine different ghostly versions of myself standing simultaneously around these street corners as if time is playing out all at once. As if my memories are performing like wind-up-toys on little predetermined loops. An eight-year-old me, all elbows and pink pigtails, plays hopscotch on the crosswalk while across from her, a seventeen-year-old version stands sweaty in a restaurant uniform waiting for the light. My thirteen-year-old self bikes past with a clunky school-issued laptop satchel bouncing off the back of her knees. A five-year-old me sits with Dad on the curb, clumsily spitting sunflower seeds at his shoes. He holds her tiny

hand skin to skin as they cross to watch her brother benchwarming at the tee-ball game.

In the wintertime, the ice rink in town opens for one-dollar local skate day on Mondays. All around the edges of the rink are worn out and ice-encrusted advertisements for local businesses. I was never a talented skater, so I slammed into each business, year after year, in an endless parade of one-dollar crashes. There was Bob’s Diner, where Shannon with the blue eyeliner called me baby and winked on Sunday mornings when I slouched in hungover asking for extra coffee. The Perfect Wife, a tavern owned by the mother of the first boy who ever held my hand. Bromley Adventure Park, where we left the climbing wall with sunburns on our forearms and foreheads. R.K. Miles, the hardware store below the old dance studio, The Hair Retreat, where I got my first job answering the phones, Mother Myrick’s, the bakery solely responsible for every birthday cake I ever had. Driving through town, I know them all. Little versions of me stroll in and out of their doors, endlessly on tiptoe to steal pastry samples, clocking in, shaking hands, chatting about the daughter’s piano recital or college commitment or the next storm on the weather forecast.

Like the back of my hand doesn’t even begin to cover it––I know my hometown like my chest knows to keep rising and falling, like clouds know when to rain, like leaves know which way to face the sun. I belonged to only one place for my first eighteen years on Earth. It’s written on the back of both my hands, both my arms, all my bones, every atom in my body.

At the beginning of September, my mother called to tell me that she and my father are selling the house and looking at real estate listings in the city up north. I was sitting on my back porch in Connecticut and had to carefully measure my voice so she couldn’t hear the tightness gathering in my throat. I was angry at myself for feeling upset. It isn’t a new idea. It makes sense, really. My brother

and I have both been gone long enough, and there’s nothing keeping them there. They should start a new chapter somewhere else. What’s stopping me from going back someday? It’s only one stupid little town. One tiny stupid suffocating town. And yet the tightness was still there, and after I hung up the phone there were tears, too. The choice between Big Route 7 and Little 7A: both will take you home from Bennington, but I avoid 7A because it usually has a cop lurking after the speed marker in Arlington. The sharp jab in my throat when I play soccer on a field after frost and think yes, it’s October. The topographic map of snow salt lines on my winter boots. The Christmas lights. The farmer’s market. The roundabout. Zucchinis, carrots, and tomatoes; fresh hummus from the farm; a whole baguette just for me. My brother and I tangled in the sheets on a futon in the one room with air conditioning. The Mexican restaurant where my piano teacher’s husband worked as a chef and hung himself in the kitchen. Thursday wings night. Meatless Monday. Snow days. French braids. Curried fruit. Spin the bottle. The building that was a retirement home, then a frozen yogurt shop, then a sporting goods store, with nothing now but cobwebs in the windows. Sliding down the banisters after basketball practice. The buzz of our homemade garden watering system. A lost tooth and a power outage. The 100th day of middle school. 100 days until graduation. Mom waiting outside the movie theater on my first date. The movie theater torn down, replaced by a TjMaxx. A forged note to a gym teacher so the boys wouldn’t watch me try to swing a baseball bat. A patch of scorched earth where David’s house burned and we sent his brothers our old clothes. A big green box labeled XMAS SHIT. Harry Potter on Dad’s iPod. Van Morrison on Dad’s iPod. Gypsy Kings on Dad’s iPod. My grandmother nodding approvingly, that hairstyle looks Very German. Cheese fondue on a camping trip, let’s be ridiculous. A flower in the quiet garage, have you ever seen anything so still?

When people talk about leaving something behind they like to use the word possibilities. New beginnings. One door closes another door opens. The future is waiting if you just get out there and look. My last years in my hometown I tried my best to lean into look––tried to believe my future was bigger, or better, or at least meant for something more. I grumbled gotta get out of here through gritted teeth. Scoffed a lot. Yanked up my collar against the cold, kept my arms perpetually crossed, flipped off other drivers on the road, kicked puppies and knocked ice cream cones out of babies’ hands. None of it worked. Leaving was hard and losing will be even harder. So what happens next? We lean into it––we cry fat ugly tears, we sing songs, lay out memory crumbs in poetry, in journal entries, in essays and stories to separate ourselves. As if looking at the hole with a magnifying glass will protect us from the parts that actually hurt. Time is reaching out with her long spindly fingernails and scraping away at the threads still connecting us to the girls we used to be, the worlds in our rearview mirrors.

Before I left home for the first time a few years ago, I had a dream about a drive through the streets at night. LED lamps cast shadow stripes across my hands on the steering wheel and the road signs were all wrong––advertising places that didn’t exist and pointing arrows toward streets I knew under different names. Where Sammy’s should have been there was an industrial super-size Costco. My elementary school had a fancy new sign out front. The empty shop fronts were full and glowing brightly from inside. I didn’t have to put my hand against the glass to know the car windows between me and the town were impossibly thick.

It was only partway through the dream that I caught a reflection and realized I wasn’t alone in the car. Some imaginary little girl––my daughter maybe, or a younger self––was looking at me with my own blue eyes from the backseat. The both of us were together in some future space, roadtripping to nowhere, just passing through. I

Issue VII: Threshold

started narrating to her out loud, describing all the things that used to be.

This road was called Highland. There was a gas station right there. Emma broke her wrist falling out of that tree. This roof was rebuilt when the hurricane blew it away.

That department store was the first time I felt pretty.

I was seeing her, seeing it too.

It was beautiful, I say.

It was mine.

Look.

Telling Maya About Haddam

Sabrina Tian“There is a 70 percent chance that I will feel miserable at 5PM tomorrow. The forecast says we’re getting rain. You mentioned driving up to Santa Cruz last weekend, I wish I could have been there.

My friends took me on a drive tonight to lift my spirits, but the roads in Connecticut were built to make you sick. Two-way, winding, empty, the treat of making roadkill. And the houses keep a distance from each other like old work boots with the leather peeling off. Some of their windows were lit, begging to be stolen, pawned off as architectural salvage.

We finally stopped at an abandoned factory in Haddam, and parked beside a row of cranes. My friends walked across the street and sat on a stone wall. The street lamps were so sparse, I couldn’t see anything but the burning of their cigarettes, a little orange lighthouse. If a car passed by, its headlights would flash the image of three faces who loved me a lot.

I remained in the car, appreciating their orange-colored kindness, admiring the density of the high trees, smelling for farms. I thought if I inhaled deep enough, I could fill my body with the soil.

Connecticut skies have so many stars. In three hours, count how many you see in California and call me back. Let us compare our findings.”

Florida Killed My Dog

Ella Spitz

We flew my dog to Florida to cheer up my dying grandpa. The air is too humid to let things breathe. Florida is where things go to die.

Raggedy panting and all-new matted fur. Mom told me she held her to her chest, so their hearts were touching. She said she felt her heart fade. The last dog heartbeat.

It is something in the air. Floridian air is full of heavy stuff and it makes things empty. Those parts of sun rays that kill. Florida is where my grandpa wants to die.

Do I look like my dog died last night? I’m told my eyes don’t get puffy. I keep it all in my pocket, adages of grief stuffed in my jeans. I’m scared to go home and breathe the empty air.

She stayed by my grandpa’s side. We were worried her nails would break his withered skin. Skeptics will say she kept to him only because he dropped the most food. I say it was love.

They spread her dog ashes off the Florida coast. She’ll be in the air soon enough. I’ll breathe her again.

Landlubber Jonah Barton

Landlubber Jonah Barton

After sweet potatoes and dead deer, past the wood burning stove, you walked me up to your room till there was no one.

It was there, that Thursday, that you showed me the ocean you liked to keep in your front jean pocket.

I asked you how long it’d be till the whole thing spilled down your leg, water collapsing to the floor, an octopus wrapping itself around your ankle, a loose coral gashing the flesh of your thigh.

We’d stand in water rushing up our bodies, seawater soaking the wool sweater you once knit for me, anchoring my feet to your floor till my lungs were filled exactly.

In stillness, your mandolin would fill and sink, sitka spruce now soft to the touch, its strings tied to rusty hooks, reeled in sea creatures drifting to the ripples of a bluegrass ballad lost along the way.

When I looked back up at you, all I could see was your hair floating above your head the way seaweed does, breezy and warm,

a smile drawn across your face, as the waves kept crashing.

bone flutes

Nicole Leenote: bone flutes, carved from a bird’s (like a crane) wingbone, were traditionally used to signify a successful hunt, and a return home.

there are roads you take and there are roads you know and there are roads that are taking you to places you do not know but your bones did and that swoop in your stomach does

it’s the tug of a lead a leash going snap pulling taut, as if shocked or releasing some great admission of guilt before going limp and dead it has pulled you here, chivvied and led you halfway from home, pulled by the nose toward some familiar scent by a familiar lead

imagine the leash; picture it in your mind see how it winds?

see how it stretches out, sprawling for miles, meters? it crosses mountains, snakes atop choppy waves, snags on tree branches, and catches on your heels that whole spooling history of where it has been, where it has come from and where it, finally, has brought you tripping you up as you cross borders, boundaries, bridges that swallow rivers, that become roads, leading to concrete seas across it all, the expanses and the alleyways, it has led you back, played the piper, taking you down a road you do not know but your bones did. the air is not clean, and the land is not new. you are standing on something haunted and the lead is slack and you discover that you are just another ghost come back to call the haunting home.

The Meet-Up

Georgia Groome

“What would you do if I died?” I asked my mom on a brisk Sunday morning.

“I think I would kill myself pretty immediately,” she answered.

It was autumn, I was seventeen, and we were walking our rottweiler-marked French Bulldog, Fonzie, home from our local dog park, which lay nestled between the Chelsea Waterside soccer field and the Hudson River. It was a tradition that began my senior year of high school: wake up early, go out for coffee, and take Fonzie to what was called the “French Bulldog Meet-Up.”

The meet-ups were events hosted by Fonzie’s dog walker, Jeff. Every Sunday morning at 10:00 am, restless, wheezy frenchies on leashes held by hung-over, wheezy adults flooded the Chelsea Waterside Dog Park on 23rd and 11th. Though my mom and I wanted the meet-ups to be an opportunity for Fonzie to fraternize with her pinched-face peer pups, each week she—without fail—would park herself next to us and, with a face void of any expression, ping pong looks from the packs of barking dogs to the expectant faces of my mom and me.

Amber leaves stirred listlessly at our feet as we made our way down 22nd and 10th: a quiet, quaint residential street splintering the commercial expanse of downtown Chelsea. Condensation from my coffee cup wet and cooled my palms while Fonzie sniffed at a discarded chicken bone. My mom tugged her away from the bone and toward her side so that Fonzie would walk in pace with the measured gate of her pink Nike running shoes. Fonzie complied, obedient though resentful.

Despite being in her mid-fifties and a chronic outfit repeater, my mom was stylish. Above her pink running shoes—running shoes

that she wore with such religious fervor, they might as well have been grafted onto her skin—she sported a pair of boyfriend jeans, a fading gray sweatshirt, a black bomber jacket, and an orange beanie. She pushed her thick, square-shaped glasses onto the bridge of her small nose. The frames were yellow-tinted, and beneath them, she looked pensive, assured.

“Yep. I think I would kill myself pretty immediately,” she replied again, this time with even more conviction. We were speaking to one another casually, but conversations of this nature weren’t so common between us.

In my high school days, we talked about all of our thoughts all of the time, and never with filter, pretense, or reluctance. During the week, we hammered out logistical, professional, and academic matters. We discussed when we would eat dinner, whether we should order or cook, what show we should watch while we ate, how many email drafts I needed to run past her for approval, and then whether or not it was a smart idea to call my grandparents to tell them about the trip that we planned to take over winter break (we settled that if we waited a while longer, it would be impossible for my grandma to invite herself to the vacation, or, more aptly put, to convince and guilt my mom into thinking that she, of course, deserves to be with her two favorite girls and, honestly, how did we not think of her sooner?). On Saturdays, we discussed our Friday nights, our upcoming weeks, and our anxieties, hopes, and predictions about who would win Love Island or the Super Bowl or my upcoming basketball game against my high school’s rival team. But, by the time Sunday rolled around, and all quotidian, banal conversation had been exhausted, all that remained was existential curiosity.

“Kill yourself pretty immediately? Oh, ok. That’s awesome,” I responded sarcastically. Leaves crushed underfoot; Fonzie waddled over slats of pavement in a zigzag.

“Well, what would you do if I died?” She parroted.

“I would probably kill myself, too.” At this, she turned to me, an expression of rage and shock shadowing her face.

“Georgia, you cannot kill yourself. You… are… not… allowed… to… kill… yourself.” She said this very seriously, as if this hypothetical situation was highly probable. As if I would follow her instruction if it were.

“Why are you allowed to and I’m not?” I asked. I remember thinking how futile and inconsequential this argument was. Still, I couldn’t help but feel defensive.

“Because if you died, I would have nothing else to live for. But if I died, you would still have the whole world.”

The whole world, by which she meant a relatively untouched life. Sometimes I forgot that my mom wasn’t my sister and that we didn’t share a singular existence. That she was thirty-eight years older than me, that she lived a life before me, one that I’ll never be able to access. That she was a real person in a way that I wasn’t yet.

That she was the parent and I was the kid. That she would die before me, if things went as they were meant to go; the thought alone was, and is, enough to bring me to tears. It was endearing to me that she believed that I would have the whole world in her absence. She didn’t know that I built my entire world around her.

“That’s fucking ridiculous,” I told her. “You would still have the whole world, too.” We continued to walk, Fonzie pausing occasionally, us mindlessly pulling her along. “Can you please promise to not kill yourself if I die?” I asked earnestly, as if this hypothetical was highly probable. As if she would follow my instruction if it were.

“No,” she said, with force. My mom has never lied to me, not once in her life, and the gravity of her certainty both scared and secured me. Being the center of her universe came with immense responsibility—I knew that she would die for me—and immense idolization—I knew that she would die for me. I was a life force, a loaded gun.

“Fonzie!” my mom exclaimed. “Bad!”

Together, we watched our very small dog hack down a piece of discarded pepperoni pizza. And then, together, we never spoke of our deaths again. Only adjacent topics like where we would like our ashes spread and could you please make sure my urn is blue?— you know the shade, the one that’s my favorite.

Searching

Kiluwe MbuyuYesterday,

I am wandering the riverside

Listen close and you’ll hear me

The shuffle of wayward footsteps

A few shallow whistled notes

The crunch of weary stones beneath my feet

The subtle ethics of everything eludes me

But the grand truths buried in the sand

Amount to this:

You only really begin

When you understand There’s nothing to be done

Night Meditation Hannah Langer

The forest on the other side of the fence. Who’s there? Ten year old hands, Sneaking through long-nailed bushes, Tall trees belonging to dirt Birch eyes shrouded over me.

In the night expanse

What are you if not alone?

Wrinkly-fingered nun slouched into oak chair And told us about the intimacy of darkness. Night is vulnerability. Hearts exposed and pillowy.

I fall asleep with your chest touching my back, River pushing gently against the bank. But I am pulled back Into that forest, Trees sprouting from boggy ground Into the grove where you can’t find me.

Turmoil After a Mediocre Date

Nate SchultzI fought against thought and hoped hope would matter. But my trickles of doubt have struck no sweet surprise. So, I soak up our time with my half-hearted smatter. Oh, I wish you’d see through it, with your soft summer eyes, How I don this disguise in preparation to scatter.

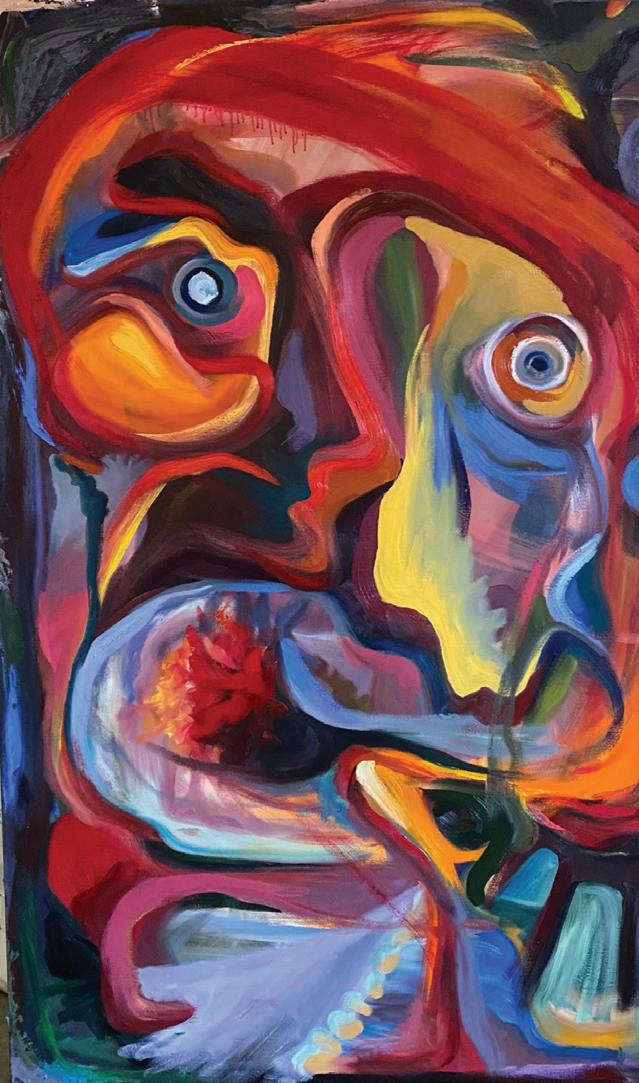

Katia Michals

Katia Michals

Blank Blinker Imogen Shearmur

I had met him earlier in the night at a New Year’s Eve party in Eagle Rock. He told me his name – it was Bradley – but “Stars Are Blind” playing over the speakers rendered the consonants indistinguishable. He wasn’t tall and he wasn’t very handsome, but he had an incredible mustache as thick as a broom’s bristles. As the clock struck midnight, the DJ announced the new year, and he leaned in to kiss me, and I liked his mustache so I let him.

“I think I just kissed someone named Bracelet,” I told Emma in the bathroom later, and when we emerged, he invited us to another party at a speakeasy in Highland Park called the Blind Barber, his voice rising on “speakeasy” to make sure we knew that he was the kind of man who knew about speakeasies.

He called a car. We piled in. Even though there was plenty of room in the back, I sat on Bracelet’s lap.

“Where are we going again?” asked Emma. “We’re going to the Bread Baker,” I replied with confidence.

My silver dress rode up as our driver inelegantly piloted the car, seemingly determined to scrape against the curb as often as he could. I expected to feel the rough tips of Bracelet’s fingers under the hem of the dress, but he kept them on my shins. I thought how very respectful he was. But I also was disappointed. I suddenly remembered that he was a complete stranger and thought that I should learn some self-respect; I was becoming a real loose woman, allowing mustachioed men to kiss me at random and feeling disheartened when they didn’t cop a feel. Then I thought I shouldn’t be so hard on myself, and tried instead to remember the name of the speakeasy, but the only thing I could come up with was the “Brick Breaker.”

It felt like we had been driving for hours. Bracelet was talking about his love for seventies soul music. It dawned on me that there was no way the man whose lap I was sitting on was actually named “Bracelet.” My shame returned twofold. Not only was I a slut, but I was a fool, too. I placed my trust in a man whose name I didn’t even know. Who knew if the Bank Builder was even real? We could be en route to a below-ground bunker, where Bracelet would bind us and break our bones with a baseball bat, or boil us in butter, or bury us alive beneath a bridge.

I vowed to make some changes in the new year. I vowed to save myself for marriage.

The car screeched along the curb and finally pulled to a stop; the Blank Blinker was real after all. Overcome with relief, I swept Bracelet into a passionate kiss. Maybe I would save myself for marriage next year.

What a Highway Sees

Amanda Dingthis city is a love language to all things temporary.

watch the stationary store, whale shaped spaghetti shop crouch on childhood shoulders then vanish for the last time. burnished, yellowing plaques uninvited from our ritual.

cling wrapped bundles of rice and egg no longer ejected from a warm mother, oil licked apron. moving to the south, where things are warmer softer, seasoned with the sea.

and so did we. did the steaming bowl decide erasing itself from a decade long menu was its way of mourning our departure? or was it no one here has a taste for those things anymore.

well. don’t expose the man illegally selling movies to their american audience. we are not american. the dvd shops are for them. 10, 15, for a pack of latest hits. not recorded in a movie theater, promise.

that small shop cluster used to be the size of my palm. now it dilates to encompass my later years, still deserted. smile at our commonality but remember that in a few years it might be all gone.

under my adult soles, the road shifts to match them. same walk with a first love. same bicycle accident. there, there, there. point them out, all of them overlaid with the tendency to writhe and grow.

concrete is not alive. don’t you know, you know? a covered car runs right through a school. a first haircut moves a girl to tears a telephone call insists on being, mother, brother. me.

those ghosts are so bright today.

Dead Ends

Gemmarosa RyanShe held it tenderly, like one might a bunny Keeping its musculature relaxed before timely slaughter.

She pushed it methodically, her knees buckling from its weight Marching longingly upwards, renouncing to Sisyphean destiny.

She feared it ferociously an inability to turn water to wine Entropic means to a dead end nowhere left to go but back inside.

It Spirals Up

Olivia RubensteinIf I can bless myself just once

Lay my own hand across my own brow and pour the anointing oil

I’ll beg the almighty for this: I hope it all feels like play forever

Rolling socks from a circle to smoothness up each leg,

Melting butter in a pot till it browns then dolloping in batter

Pouring water from a silver cup over my sun hot hair

It all feels like something

So this isn’t quite poetry

It’s more of a letter

Or A mouthful of grain

Spewed laughing across the table

I hope these little things never feel little

And tracing the veins that line my arms always fills my days

Roadmaps like the top of my mothers hands

Blue arching up, thin skin giving way

If I lived a thousand lives

I’d spend a full decade in the kitchen just stacking and Unstacking cups

I’d give a year for the spice rack

And twenty to the milk

I’d taste my way down eternity

And kiss the cracks in the counter

It wouldn’t be enough

What I wouldn’t give to live properly

To stop and talk and pay attention to every darling of the eye

Grow old alongside roses growing tall

Spend an hour thinking on every loose button and breeze

So now I walk slowly alongside the side walk

Crushing grass like grapes

Chin tipped, teeth chipped, to the sky, feet cold even in summer

When I am old I’ll make the most sense, Wrapped in white and washing blue China.

The

Lavender

Turning Ten

Rory DolanWhat the boy liked about the table was how it stuck to him; the way its modest coat of black paint seemed reluctant to release. It was sticky. Not in a bad way—a spilled drink, sap, glue on the fingertips—more like the warm adherence of sand; pliant and trusting, leaving flecks in the creases of his hands. It reminded him of the way his father would clean grime from his face, licking a thumb and holding his head in one hand, smearing the dirt away. Uncomfortable, but not unwelcome; familiar. When he ate with his elbows propped on the table—which he wasn’t supposed to do—and raised something to his mouth, there was that little pull on his fleshy underarms. Or after flag football practice, when he took off the receiver gloves he borrowed from a teammate and never gave back, the way its surface seemed to cling to his hands, but only when he tried to remove them. Only when it was time to go.

The table had never been beautiful. Not like some of the things in their house. The painting in the hall, for example: hazy shapes and water-color questions, something like the feeling of jumping into a cold, shallow pond, with all the scum at the bottom. Blue and green and silent brown. Or the lightbulbs in the hanging cone lamps above the kitchen counter, their fluorescent tubing twisted in asymmetrical helixes. His mother had ordered them from Sweden, they were meant to save energy. But then there was the table: an old coat of black paint, four legs that did not twist off, a long fissure that ran the length of its center, and a single drawer below that. It had been there before the boy, inherent to the geometry of his home, the shape of their movements, as implicit as the walls or floor, nearly invisible amidst the habit of life. Not elegant, but sturdy. Sometimes they used placemats, but never a table cloth. There was plenty of room atop it, for hands, and arms, and grocery bags, and forks and crumbs, and waiting, and thinking, and so on.

It had been there for as long as he could remember, witnessing countless dinners, registering untold conversations in the hollows of its wood. When the boy would clean the table after meals, he had learned to wipe from the center out, or else any scraps might disappear into the crack to rot in the drawer. When he was younger, he drew jungle scenes with colored pencils, always with the animals too large—tigers and dolphins the size of the trees and vines around them. He’d scatter his colors across the table, and any section that he shaded would be rubbed in the imprint of the wood grain, winding grooves amidst the pencil scribble. His mother framed them all, hanging them around her office and neatly noting his age and the year with a sharpie in the bottom right corner. He was not so young now; young enough to still see worlds in most things, but old enough to better understand their scale, or at least begin to.

The boy was ten. His mother had explained that morning—his birthday—that he was born at sunrise. So as they sat, each eating a donut, licking their fingers clean of the glaze, he reasoned he might be exactly ten years old. “Double digits!” was what his mother had exclaimed, shaking him awake gently, “how do you feel?” His mother was double digits too; forty and then some. Four sets of ten—another nice thing about his age, a neat, stackable number. The boy asked if she liked being double digits, and she responded “sometimes.” He assessed himself, and found he didn’t feel much different to the day before. If something had changed, it was not yet apparent. His mother passed him a small box, wrapped in polka dot tissue paper. Before he opened it, she insisted on taking a picture; the boy and his presents. Inside were multicolored sharpies—mighty, permanent markers—and a new box of legos. They embraced, and she told him breakfast was ready downstairs. Double digits. He decided this was a pretty good way to be for now, all things considered.

He noticed for the first time, as they sat eating, just how much the paint had chipped. By way of his mothers fingers, with their big joints and pair of rings. She stared out the window, and ran them along the table, scanning across the grain similar to how the boy would when he read, using a pair of half-pointed fingers to keep his place, to not get lost. Eventually, she would reach a point where the paint had worn away, and pause, caught on the change in texture. There were plenty of these bare spots, where the boy could see the wood underneath, and feel it too. Her forehead furrowed in unspoken concern, gathering into three long shadows. Each crease on her skin was a repetition, afterimages, tallying the passing years by the customs of her face. One summer, she had read him a book called “A Wrinkle in Time,” but it had mostly been about space, and something called a tesseract—not so much birthdays. Her concerns might’ve been lost on the boy, but her expressions were his own. When the boy encountered these paintless patches—their flaking edges—he couldn’t help but pick at them. He would poke and prod, teasing his fingertips underneath the peeling color, and pulling away satisfying little shreds of glossy black paint. The real rewards were the larger pieces, when he could pluck them in unbroken sections. He’d pass the sliver between his fingers, letting it stick on each pad before trapping it between his middle finger and thumb and grinding the paint to dust. He was doing it now, he realized, scratching at one corner with his free hand. But then the picking had always felt small, and insignificant. The paint was already thoroughly worn, chipped to where his small excavations seemed to make little difference in the overall state of things. Looking at it now, the boy felt a pang of something, in his neck and behind his ribs, a shrinking feeling, as he regarded the table’s blotchy surface. When had it gone from worn to ragged?

He had little time to dwell on it, as his mother was up and

ushering him out the door. Despite it being his birthday, he still had to go to school— a state of affairs the boy had always found objectionable. On the playground, he slipped into a game of kickball, manning the outfield as it gave him ample space to be elsewhere. Rain clung to the concrete from the night before, revealing with pools of water the places where the ground was uneven, hills and valleys that were otherwise invisible. The boy watched the legs of his classmates as they wheeled toward first base, crashing through a puddle; their sneakers, bright and velcroed, changing color— darkening as the water soaked through.

In class, the teacher passed around a section of a log with dense gray bark and rings like an overstuffed dartboard. As the boy held it, he tried to count each one and became lost in their number; the way they crowded into one another, mimicking each crook and bend in tight symmetry. Scientists studied these lines to learn about the histories of trees, the teacher was explaining, a process called “dendrochronology;” he said each syllable slowly. From greek, the word essentially translated to “tree time;” each ring, a full cycle of seasons, each drought and bounty, echoed in sharp angles till the decades smoothed the hitches. Somebody nudged the boy, and he hurriedly passed it along.

At lunch, the boy walked to the front hall to pick up the cupcakes his father had dropped off for the class. He took the tupperware, holding it out proudly before him with both hands, careful not to jostle the treats inside as he headed back to the classroom, briefly, gleefully alone. On his way, he passed the library, with its lasting, loamy smell. Outside the glass doors was a small cart of books, not stacked neatly, but in page-bending, scrappy heaps. The boy paused and crossed the hall to inspect the contents. Books with faded jackets, plagued by dog ears and missing pages, folded and crooked from harsh placement and neglect. Too-wide rectangles

with rounded corners, their cardboard covers waterlogged—some choked with mold—the same sorts of titles he had learned to read from, all rife with clever alliteration; lions named Leo, and gorillas to say “goodnight” to. Mostly, though, they were books he didn’t recognize. Paperback filler, vaguely familiar but largely non-distinct. He had likely seen them countless times, passing over their spines, unregistering, on his way to whatever might be about to grab him, immediately erasing what had almost come before. Memory was funny like that. All of them showed signs of use; a softness, the yellow of time.

The boy picked one up. The cover was nearly ink-bare, mostly a paper-white haze, spreading from the middle like rust and obscuring any title. Most of the author’s name had disappeared, now just reading “quez.” Its spine was likewise worn, so when he placed the book atop the tupperware, it fell open to the last page, revealing a small paper pocket, stuffed with a handful of checkout cards. The most recent of them was overrun with stamps, filling the entire two-column table with names and dates and then the whole surrounding area with as many pen addendums as could possibly fit on the small slip of cardstock. Dates spanning all double of his digits; names that went from almost familiar to totally unknown. A great deal to keep in order, a lot to be responsible for. Each instance, and all of the gaps. The boy did not know how long he had lingered there, and quickly placed the book amidst the heap, surprised by how light it was as he let it go.

Walking home, his father asked if he wanted to do anything special for dinner. The boy shook his head emphatically, but could not say why. When he got home, he drifted up to his room and lay sideways on the bed, letting his feet brush the ground with his shoes still on. He spent the evening lingering in the hallway, or sitting in the stairs, remaining in places where he might see his parents come

and go. Something had changed. Although it was his birthday, it seemed to the boy as if it was everything else that had gotten older, and very suddenly. Like the wrenching fear of a train leaving the station while he was still at the top of the steps; that he might be left behind. His parents ordered food anyway, and the three of them ate at the dinner table. The boy listened to them recount memories of his own life, the details choppy and strange, like hearing about old classmates whose names he had forgotten. He stared at the table, taking it in, touching it gently.

But then his parents were singing happy birthday, bringing out a cake with ten candles, lighting each one on the stove. They counted up the years, and the boy counted too. He blew out all the flames in a single breath, and couldn’t help but feel immensely pleased. Some wax splattered onto the table in little droplets. The boy decided he would do something; he was ten afterall. A plan was beginning to form in the back of his mind. They ate the cake and then he was sent off to bed, where he waited below the covers, biding his time.

He listened hard to the sounds of the house, counting footsteps and doors closing until the only creaks and groans were that of the house itself, its infrequent breathing. And when he was absolutely sure nobody else was awake, he crept out of his room, sliding his socks along the floor to keep his weight steady. When he reached the kitchen, he made his way to the table. He didn’t dare turn on a light, relying instead on the gray glow of the city outside, all the street lamps and still-lit windows. It was enough to work with. He pulled from his pocket two black sharpies, both from the pack his mother had given him, and quickly got to work. Wherever the paint had chipped, he colored, filling the voids with permanent marker. He worked slowly, shading with all the care he could muster, because, he realized, he had known this table all his life, and that meant

something. As he went, he allowed his hands to run all over the table, feeling its wrinkles, thousands of threads, petrified, mingling. When the first pen ran dry, he uncapped the next one, and kept on. And when he was finished, he stood and admired his handiwork: an all-black table once again.

In the morning light, the boy would come to find the table covered in a strange midnight camo. Not the pure-black restoration he had hoped for, but rather, where the sharpie had found wood, a purple, the same shade he saw when he closed his eyes; the table, darker, but as patchy and mottled as ever. His parents would be furious, but would relent, as it was not the first either had considered finally getting rid of the thing. But when they would try, years down the line, the boy would defend it with a fury even he hadn’t expected from himself, insisting it deserved to stick around. Until he too forgot.

But not in the kitchen’s umbral silence, under the gentle gaze of irrational hope. No entropy, no endings, nor anything like doubt. And wherever he looked, everything stayed. A passing car washed the space in a silver light, playing on the wood like an old projector, finding its topography in glowing pools, ink and paint, and cracks and grooves. The boy went and lay atop it, feet dangling off the edge, and thought about how it might feel to live forever.

nightcrawler

Gen Corazza

sun snoozes in quilted troposphere steam smell of mud and plant breath rising up up up

sky all white noise rushing

salt mines leaching diffusive osmofluid soaked unsmokable marlboro guts leaking carcinogens splintered modelo shrapnel spilling into brackish 10 proof stream

soles playing floor is lava pass over sodden spirits razing river sticks while beached sidewalk bruises (peach bluing) ribbon into alphabet soup

hello little worm how does it feel turning green?

Impending Sofia Baluyut

i steal your shoes and steal to the roof. you follow. your feet a soft sound on the stairs. we settle by the tangle of telephone cables, my cheek a canvas for your thumb’s scrawl. this morning, you hit an egg until it broke. so gentle. your posture whispers of it. and my breath is high in my chest, watching skyscrapers disappear across the river. you turn my chin. i hear the rain before it hits.

To Anna Before Her Door Closes:

Nettie HittHe put the ring on the wrong hand

Three gems, a simple band Now bound to her swollen finger In the morning.

God’s child, wife, daughter, Please anything but mother. She’s too thin, but already Guiding those adult babies

To the water, pull them out--Their drenched clothes pull Back.

To Pearl, Who Gave Me Her Piano

Lilly GitlitzAt the first sense of a parasite, the mollusk, with shells like two lustrous lips of a cartoon mouth spurs iridescent creation.

There is one picture, digitized. She has gray hair, branching crows-feet, clouded eyes emanating warmth.

Give aragonite, give conchiolin, give nacre on nacre on nacre until

She stares through the camera. Through me, it seems. I cannot help but notice that her neck is adorned with her namesake.

Time and fear layer on until one can hold a sphere of it. A pearl is born perfectly in the center.

I wonder her mother’s name. Stories of her girlhood. Her favorite songs to play. But I know nothing.

One can tell a real pearl from an imitation by scraping it against their teeth.

Pearl, you gave me my greatest gift scratched your name in it and this is all I know of you.

When the time comes, I, too, will inscribe myself into this instrument. Holy legacy. This is one cycle I will keep unbroken.