The Magazine of the Rotman School of Management UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO 2022

How COVID Has Changed Consumers Strategic Foresight: Think Like a Futurist

The Secrets to Amazon’s Success

Power: What You Need to Know

You open your book by stating that “power is misunderstood.” Describe what you call the three pernicious fallacies about power.

My co-author [Harvard Business School Professor] Julie Bat tilana and I have conducted extensive research on power and change around the world, and on this journey, we have found strikingly common misconceptions in how people think about power. The fist myth is that power is a ‘thing’ that someone pos sesses, and that there are special traits that give power to some people and not to others. The reality is that power is always rel ative: You can have great influence in one relationship and be completely dependent in another.

Second, power and authority are not the same. When we ask people to think about individuals who they consider power ful, the vast majority mention those high up in a formal hierar chy, whether it be CEOs, world leaders or bosses of different stripes. But authority is no guarantee of power, and nor do you need to be high in a hierarchy to have power. For example, in our research we have found that the most effective changemak ers in organizations are not necessarily the people at the top,

but instead those whom others go to for advice.

The third fallacy — and perhaps the most common one — is that power is somehow ‘dirty business’ and should be avoided so you don’t get sullied by it. But contrary to popular belief, power isn’t intrinsically good or bad, and it doesn’t have to be acquired via manipulation or cruelty. These misconceptions are harmful because they prevent us from understanding how power works in our lives — and make us less likely to identify, prevent or stop abuses of power that threaten our freedom and well-being.

What, then, is power made of?

Power is the ability to influence behaviour, and what allows one person or group to influence another is control over access to resources that the other party values. So, you have power over someone if you can provide them with resources that they value and that they cannot obtain easily from somebody else. Con versely, someone has power over you if they can give you access to resources that you value and if you don’t have many alterna tives for accessing those resources.

Power in a relationship is always made up of four elements: (1)the resources that another party values, and (2) how easily they can come up with alternative ways to get them; (3) the re sources that you value, and (4) how easily you can get those re sources from an alternative source.

Once you understand that these are the fundamentals of power in any relationship, you will see that power is always rela tive: You can have a resource that is a great value to one person (giving you power over them) but is irrelevant to somebody else, depriving you of influence on that person’s behaviour. And power is also always relational, in the sense that it’s not enough to figue out how much someone depends on you; you must also consider how much you depend on them in turn, because power flows in both directions in every relationship.

You have come up with a framework for shifting the balance of power. Please share its key principles. The beauty of the four elements of power is that they identify four strategies for rebalancing power in any relationship. The strategies in our framework are attraction, consolidation, with drawal and expansion. I’ll describe each.

Attraction has to do with the fist element of power in the relationship, which is the value of your resources in the eyes of the other party. To increase your power over them, one thing you can do is to increase their interest in the resources you have to offer. Any good salesperson or marketer knows that you can change how people perceive the value of a resource so that they become more interested in it, and if they’re interested in it, you have more leverage over them.

The second strategy, consolidation, concerns reducing the other party’s alternatives to access those resources. Given a re source that the other party is interested in, you want to coalesce with other providers of this resource, so that you become hard to replace, collectively. This is the strategy used by workers when they unionize, for example. The whole idea of forming a union is to make many alternatives just one. Cartels are also an example of consolidation. If you want access to oil and gas, a cartel like OPEC constrains your alternatives, giving greater leverage to the cartel.

The third strategy is withdrawal, which entails decreasing your interest in the resources that the other party has to offer. For instance, over time France freed itself from its dependence

on oil-producing countries by switching to nuclear power as its primary source of energy. Finally, there is the strategy of expan sion, whereby you create more alternatives for getting access to the resource you want so you don’t have to depend on any one of them. Securing an external job offer, for example, makes you less dependent on your current employer.

These four strategies apply to organizations competing in an industry as much as they apply to an individual negotiating conditions of employment or to a group seeking large-scale so cial change. Just as the fundamentals of power are universal, so the four strategies to rebalance power are applicable everywhere.

You believe grasping the dynamics of power is critical, not just for achieving our personal objectives, but for shaping our collective future. What are the most important things to un derstand about power with respect to the latter?

If you take seriously the idea that power comes from control over access to valued resources, you realize that this access is very un equally distributed, depending on the environment in which you operate. If you are a young woman in certain parts of the world, you need to fighttooth and nail, and even risk your life, for the right to go to school — something inconceivable for a young girl in a country like Canada. The resources you have access to in your personal life are entirely dependent on the environment in which you are embedded.

Similarly, your country’s system of government will have an outsized impact on your ability to shape the collective future of your family, your community and the direction of your career. If you will live in an autocracy, your voice will be silenced when ever it is in disagreement with the people who hold the reins of power. If you live in a democracy, you have a much better chance of voicing your point of view, even though such freedoms are al ways threatened and need to be guarded fiecely. Consider the ongoing struggle in the United States to limit the right to vote of certain communities.

All in all, your personal power and the career opportunities you have access to change dramatically, not just based on your tal ent and determination, but also based on the political, economic and environmental structures that constrain and/or enable you. That’s why it is impossible to understand your own power with out understanding how the overall system around you functions, and how power is distributed within it. In the book, we chose not

The most effective changemakers in organizations are not necessarily the people at the top.

to confineourselves to the analysis of power in the organizations where many people work or in their professions and industries. We have chosen to link power dynamics to the macro dynamics in society, because the two are intertwined and you must under stand both in order to navigate power in your personal life — and to be an engaged and informed citizen.

As you indicated earlier, in organizations, some people have a lot more power than their title suggests, while others have less. How does this happen?

This has to do with the misconception that power and author ity are one and the same. People in organizations have authority based on their rank in the formal hierarchy, and this allows them to issue orders and make decisions. But while authority lets you demand compliance, it can never command commitment, unless it provides people access to resources they value

There are ways other than formal rank to gain control over valued resources in an organization. One has to do with the role you play in the organization regardless of hierarchical level. When your role is essential to the functioning of the organiza tion, you gain power because you control access to something that people value deeply.

A classic study conducted by French sociologist Michel Crozier illustrates this point. Crozier visited a tobacco plant in France and observed that the foremen — who had formal au thority — were actually not the ones with the most influence. The group that had much more sway were the employees responsible for machine maintenance: The machinery would break down periodically and interrupt production, which impacted every worker in the plant, because they were paid based on their pro ductivity.

To retain their control over this highly valued resource, the maintenance personnel chose not to codify any of the instruc tions to repair machinery, so that when something went wrong, everyone was dependent on them to fixit. This control over the most valuable resource in the plant gave maintenance personnel outsized power compared to people of higher rank. So, playing a role that is critical to the survival and thriving of an organization allows you to exercise influence.

The other source of power that we explore in detail in the book is the informal networks that develop within a company. Any formal organizational chart tells only half the story about

who has power. Behind every chart there is always an informal network that is determined by people’s discretion in choosing who they want to talk to and who they want to share informa tion with. People who are prominent in this network gain access to — and often control — highly prized resources such as knowl edge about opportunities, giving them influence even when their formal rank is not particularly high.

There is therefore a fundamental difference between for mal authority and the many informal ways in which people gain control over resources that are of great value in an environment. That, at the end of the day, is what gives you power.

Describe the critical roles of humility and empathy in wielding organizational power. Power is essential to taking charge and leading change in organi zations, but it makes you vulnerable to two insidious traps: hubris and self-focus. These traps can not only erode your own effec tiveness but also undermine your team’s. Effectively exercising power while avoiding its pitfalls depends on nurturing humility as an antidote to hubris and cultivating empathy as an antidote to self-focus. In the book (and in our article in the September 2021 issue of Harvard Business Review), we detail the many ways any one in a position of power can develop humility and empathy in themselves and in their colleagues.

Consider empathy. Far from being a fied quantity that can not be changed, empathy is up to us to cultivate, and the develop ment of empathy requires us moving past a view of ourselves as independent from others to a view of us as interdependent with others. Once you recognize that we’re all interconnected and that our actions have ripple effects on other people, you become much more interested in their perspective, and this allows you to empa thize with their situation.

We detail many ways you can accomplish this expansion of your empathy in both your personal and professional life. One is to ask people — especially people in managerial positions — to work for an extended period in lower-level roles in your orga nization or industry. Many companies do this. We know of one that asks new managers to work as a call-centre agent for eight months before they start in their management role — the idea be ing that you become much more aware of what it means to work in lower-level roles and understand life from the perspective of others who have less privileged positions.

By cultivating humility and empathy and implementing organizational structures that ensure true power-sharing and accountability, we can avoid the twin pitfalls of hubris and selffocus. Leaders who do so will boost their own effectiveness and facilitate exceptional performance from their teams.

Can you think of an example in today’s world where you see power being used in an optimal way?

We see examples of power being used for good all the time! Re member that power is exercised whenever you give someone ac cess to resources they value. What people value varies tremen dously, and if you use your power to give people access to positive resources — such as a feeling of achievement, a sense of belong ing, autonomy or of being a good, moral person — that can really make power a force for good.

In the book we tell many of these stories. One is about an alumnus of the Rotman School who took a job right after finih ing his MBA as a strategic advisor to call centres in a large orga nization. As you might imagine, call centres are not necessarily great places to work. The agents are often subjected to customers who call not because they’re delighted about your service but be cause they are irritated or frustrated by it in some way. The con versations are often fraught, and morale can be quite low.

That’s exactly what this newly minted MBA found when he started in this role, and what we describe is how — with zero formal authority over the call-centre managers or agents — he dramatically improved the work environment and the lives of the agents. This was a perfect example of working really hard — and really smart — to identify what people value and using your power to deliver the resources they need most.

In just six months of working with these folks and support ing them, this one person doubled the performance of the call centre and, more importantly, greatly increased the agents’ feel ings of empowerment, autonomy and job satisfaction. These are big impacts that can change people’s work and life for the bet ter. So, absolutely, power can be a force for good. This is true of a single individual taking the initiative to help other people, and it also extends to large movements that gain and use power to create positive social change.

For readers who want to be part of the solution of achieving ‘power for all’, what is the firt step?

The fist step to achieving power for all is for each one of us to un derstand how power works. Only when we dispel our misconcep tions and see through its inner workings will we be able to engage with it appropriately and see that ‘power for all’ is essential for a healthy society.

What we explain in the book is that power concentrations and vast power imbalances have terribly detrimental effects on people individually and on society at large. A few people benefi greatly from a massive power advantages, at least in the short run, but the prosperity and the health of our social systems is deeply damaged by persistent power imbalances where some people have it all and the vast majority have little or nothing.

Our book is not only an invitation to everybody to under stand and engage with power so they don’t feel jostled by the politics of the workplace; it is also an invitation for us all to re alize something extremely important: Only when we become aware of our interdependence with each other and the political, economic and natural systems around us can we stop extreme inequality from damaging the well-being of so many — and de stroying our ecosystems in the process. Armed with this under standing, we have a chance to live on this planet in harmony and accomplish great things together.

Power concentrations and imbalances have terribly detrimental effects on people and on society at large.Tiziana Casciaro is the Marcel Desautels Chair in Integrative Thinking and a Professor of Organizational Behaviour at the Rotman School of Management. She is the co-author, with Harvard Professor Julie Battilana, of Power for All: How It Really Works and Why It’s Everyone’s Business (Simon & Schuster, August 31, 2021).

You and your co-author spent a combined 27 years working at Amazon, sharing founder JeffBezos’ conviction that the long-term interests of shareholders are perfectly aligned with the interests of customers. Please unpack that belief for us.

It’s more than just a belief — it’s an unshakeable conviction that is embedded into the company’s thinking and behav iour. The idea is that if you constantly focus on addressing customer needs and solving their problems, things will work out over the long term for your company. Amazon’s suc cess proves that when you have customers’ best interests in mind, they reward you with trust and ongoing business over a lengthy period of time.

Some leaders think that if you adopt this kind of longterm mindset, it will take too long to get where you want to go, but Amazon’s experience has been just the opposite. There are less ‘zigs’ and ‘zags’ focusing on short-term needs that don’t actually accrue long-term value. If you’re focused on hitting a quarterly number and you’re throwing together a promotion, typically you’re pulling demand from a future period into a current period and not really creating anything new. So on the fist day of the new quarter, you’re back to where you started from. If you had devoted those resources instead to building value over time, the results will accrue in this quarter and the next quarter.

It has been said that the Amazon culture consists of four things. Please summarize them.

At a conference many years ago, someone asked JeffBezos what Amazon’s culture was all about. He said, “Really, it’s four things.” The fist element is a complete customer obses sion instead of an obsession with competitors. The second is a willingness to think long-term, with a longer investment horizon than most of Amazon’s peers. Third is an eagerness to invent, which, it is recognized, goes hand in hand with a certain degree of failure. And the fourth aspect is taking pride in operational excellence. That is particularly impor tant, because much of what a particular team does is not seen by anyone outside of the team — so everyone needs to get all the little details right, throughout the company.

Amazon takes a rather unique approach to hiring. Please describe it.

The company’s ‘bar-raiser’ process is a data-driven exercise that has four key elements to it. First of all, going into an in terview, the interviewers know exactly what data they need to collect from the candidate. Amazon has 14 officia‘lead ership principles’, and each interviewer is assigned to cover offtwo or three of them. Their task is to gather data in those specificareas. To achieve this, they use a technique called ‘behavioural interviewing’, which involves asking about the candidate’s past performance. Research shows past behav iour to be the best predictor of future performance. Then, with the data they collect in the interview, they ‘map’ the candidate’s past behaviour to the 14 Amazon leadership principles.

The second key to this approach is that there are pro cesses in place to remove bias from the interviewing pro cess. After the interview, each interviewer has to write a verbatim account of the interview. They can’t compare notes with other interviewers or discuss the candidate with anyone until they have written out that feedback and in cluded an indication about whether they would like to hire the candidate or not. This prevents the, ‘Hey, this candidate

was great, you have to go in there and sell this person on the job.’ Everyone has to go in and objectively obtain specific information.

The third piece of it is that candidates for a particular role see all of the same interviewers. Given the process, by definitio, no one interviewer is going to have a com plete set of information about the candidate. They are only tasked with getting a couple of slices of the candidate’s pro fie to create a larger map tied to the leadership principles.

Lastly, there is a specificrole involved called ‘the bar raiser.’ This appointed individual is assigned to every inter viewing process and is typically not part of the chain of com mand of the hiring structure. As a result, they have much less bias as to whether a candidate gets hired or not. ‘Ur gency bias’ is a major issue in hiring. People think to them selves, ‘I need to hire three people quickly or my team won’t get our work done for this quarter.’ The bar raiser doesn’t have to worry about that. Their job is to make sure that the candidate who comes on board has met — or raised — the overall hiring bar. The bar raiser has veto power, even over the hiring manager: If they don’t feel the candidate meets the Amazon bar, they can exercise veto power and the per son is not hired. In practice, this veto power rarely gets used.

In the post-interview debriefs, the bar raiser walks the hiring team through the hiring process. Everyone reads all of the feedback, which is a great way to learn about tech niques that other interviewers use to obtain pertinent infor mation about candidates. Like any good process, this one is simple and can be easily taught. And the best part is, the more you do it, the better the process gets.

Another of Amazon’s leadership principles is ‘working backwards’ from the desired customer experience. What does that look like?

This is the process Amazon uses to vet ideas and decide whether to turn them into a product or new feature for cus tomers. At its heart, the working-backwards process is about starting from the customer experience and working back

from that. It sounds simple, but it’s actually very different from the way most organizations make go/no-go decisions about moving forward with ideas. A lot of organizations use something like a SWOT analysis, asking ‘What are our strengths? What are our weaknesses? What are the oppor tunities and threats we face? What are our competitors do ing? One word that is not even mentioned in all of that is customer. So, Amazon threw that approach out the window and said, ‘We are going to — front and centre — make sure that the customer is involved in this vetting process from the moment an idea comes up.’

The tool that Amazon uses with customers in the working-backwards process is a written document called the PRFAQ, which is short for ‘press release and frequently asked questions.’ When a team has an idea, the fist thing it does is write a one-page press release about it. Having only one page forces them to focus on the issue at hand. The press release has to clearly state what customer prob lem they are trying to solve, and it has explain to the cus tomer what the solution is. Then, they have to tell the cus tomer why this is a worthwhile product or feature for them to investigate and either use or buy. If the team is not satis fied— if this document doesn’t make them want to run out and get the product or use the service — they go back and rewrite the press release. Working backwards is an itera tive process.

Once the team has a press release that everyone is sat isfiedwith, they move on to the frequently asked questions document. There are two components to this: an external FAQ and an internal FAQ. The external one includes ques tions and answers that explain to people outside of the com pany about this new feature or service, how much it costs, why anyone should change their behaviour and use it and how is it going to make their life better.

The internal FAQs are all the tough questions around bringing the new feature or service to market. Things like, can we build this with materials less than $150? Are we go ing to build our own sales force for this or partner with an

external sales force? Again, this is an iterative process, and once the team agrees on the document, the whole package is presented to the leadership team. If they findthe team hasn’t asked all the tough questions, they are sent back to do a rewrite.

Very few ideas make it through this process on the fist round. But once all the requirements are met, then and only then can the project be greenlit and the resources allocated to move it forward.

Amazonians are not fond of PowerPoint decks or large, lengthy meetings. What are they replaced with? They are replaced with ‘narratives’, which are essentially memos of six pages or less. For a standard one-hour meet ing, six pages is the maximum length for a narrative. Ama zon stopped using slides in 2004 as an experiment for meet ings where teams would come in to present to Jeffand his senior management team. Slides can be used if you’re talk ing to a large audience in an auditorium, but for decisionmaking processes, or where you’re getting a group together to communicate an idea, they use the narrative concept ver sus slides.

Jeffhas said this was one of the best decisions Amazon ever made. Written narratives allow the reader to gain a deep understanding of complex issues to make better informed decisions. How do they achieve that? First, they force the writer, or the writing team (because it’s usually more than one person writing it) to clarify and synthesize their idea and present the story arc and all the information in a cohesive format. It’s much harder to write a six-page narrative than a slide deck, and you can’t just whip it together the night before. You have to go through multiple drafts, send it out to the team and get feedback until you crystalize your thinking.

The second advantage of this approach is that it makes the ideas matter, versus the presentation itself. You often hear people say, ‘Wow, that presenter was so engaging’ or ‘That was so boring!’ At the end of the day, customers don’t

care about any of that. They care that companies make the right decisions to provide products or services that make their lives easier.

As a result of this approach, ‘presentation bias’ is re moved from the equation. You can avoid having a very charismatic presenter with a so-so idea convince a group of people to make a decision the company probably should not make; or on the flipside, you can avoid missing out on a great idea described by an awful presenter. You can also convey multi-causal arguments better in a narrative than in a linear slide format. Amazon has found that this approach allows people to absorb about 10 times more information for the same unit-of-time investment.

Since leaving Amazon, you have introduced some of its tools and frameworks into other organizations. Which are at the top of the list?

For smaller organizations, it is very important to get your own leadership principles defined,because that really deter mines how people are going to make tough decisions when you’re not in the room. I always tell organizations that don’t have any definedprinciples to get some. You have to defin who you are and how you are going to operate in the world.

The second thing is to implement a hiring process that enables you to bring people on to reinforce those principles. If you have a five-person company and you want to grow to 50, you need to ensure that you are bringing on people who will reinforce your principles, or your company is going to change. You have to work really hard to get the culture you want.

For larger organizations, there are good lessons to be learned from Amazon’s operating cadence in terms of focusing on input metrics versus output metrics and the working-backwards process. Those really change the ways that companies build and introduce new products and how they look at managing businesses, both in the short term — where the details matter — and over the long term, where you’re creating customer value.

Overall, I really believe Amazon has advanced the fild of management science in terms of best practices for build ing and running an innovative organization. Taken togeth er, the processes we’ve talked about — from the bar-raiser process to linking everything to definedleadership princi ples — are things that every organization, small or large, can learn from.

Even before COVID-19 hit, there was evidence that globaliza tion was unravelling. Please describe the scenario and how the pandemic has affected it.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financialcrisis and before CO VID-19, slowing growth and declining economic standards led governments around the world onto a path of deglobalization. Facing growing populist pressure, many adopted protection ist policies they hoped would shield their industries and work ers. Growth in trade stalled or declined for some countries and we started to see more regionalization and balkanization. Some even broke away from global trading blocs. Brexit is one exam ple, and President Trump’s‘America First’ campaign is another Today, the world is even more ‘every nation for itself’ than before the pandemic. As global growth remains weak, countries are focused on making sure that their own economies and people get access not only to economic growth, but also to vaccines, and this mindset does not bode well for globalization. Even if the U.S. is back on its feet economically and health-wise by the end of this year, the estimates are that countries like India will only reach herd immunity in 2023. This suggests that aspects of trade and

the movement of people through global travel will remain stalled for years to come.

Against this backdrop, there is evidence that the five pillars of globalization are under threat: trade in goods and services; capital flows that drive, fund and fuel cross-border foreign direct investment (FDI); immigration; a commitment to global rules and standards; and the stature of multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. It is reasonable to assume that the post-pandemic era will be charac terized by further steps towards deglobalization, as protection ism becomes entrenched across the five pillars.

Talk a bit more about how threats to globalization’s fie pillars are materializing.

The World Trade Organization has partly blamed slowing growth since 2018 on new tariffsand retaliatory measures, not ing that global trade growth has flatlined in the past decade at around three per cent. Global trade treaties are moving towards more bilateral or regional negotiations and less multilateralism. For example, on the back of Brexit, the UK is in negotiations

PORTRAIT BY SUSAN HINOJOSA (MSUSANHINOJOSA@GMAIL.COM)A board member for 3M and Chevron shares insights about the state of globalization and economic growth — and explains why China is the antidote to deglobalization.

independently with the U.S. and Japan; and the Trans Pacific Partnership has created a selective agreement for preferential trade access by 11 countries, including Canada.

Global capital flows are also being disrupted. We have seen capital controls increase as countries began to hold on to capital and limit the amount that flowed across borders. FDI fell for three consecutive years, from US$2 trillion in 2016 to US$1.3 tril lion in 2018. Capital flows to developing nations have also de clined on the back of the pandemic in terms of FDI. More than US$83 billion flowed out o f emerging market debt and equity investments during March of 2020.

Immigration has become a hot-button issue, making it hard er to hire the talent to support economic growth. An anti-immi gration stance has led to policies such as Trump’s ‘Buy American and Hire American’ executive order, which restricted the entry of highly skilled workers into the U.S. In Europe, anti-immigration sentiment contributed to Brexit, and rising populism has fuelled a marked change across the political spectrum, with a swing to ward leaders who favour closed borders. As protectionism takes hold, employers everywhere will face hurdles recruiting staff from the global talent pool.

With respect to global rules and standards, there has been a notable decline in government commitment to these, placing the spread and transfer of the best ideas across the world — which are key to productivity — at risk. As China emerges as the leader in technology, leading the race in terms of facial recognition and some other aspects of AI, we are seeing a breakdown in global standards around intellectual property.

If you are looking for evidence of the breakdown in global cooperation, look no further than COVID-19. Not only do we see a split across developed and developing as well as democratic and non-democratic countries, but also within democratic countries, we have seen very differenta pproachest o pandemic response and vaccine rollout. As we speak, Toronto is still in partial lockdown, along with France, while places like

the U.S. and the UK are opening up. There is no coordination whatsoever happening, challenging any semblance of global cooperation.

McKinsey has predicted that global growth rates over the next 50 years will be only half of those seen in the previous 50.What are the implications for today’s leaders?

I know there are people who would adamantly argue against it, but in my view, we absolutely need economic growth, for three reasons. First, without it, we will see a breakdown in human progress and a loss of living-standard improvements. Second, there is considerable research showing that without economic growth, you cannot sustain a middle class, and without a middle class, political rights are negatively affected and the democratic process suffers.

The third aspect is that without economic growth, we would findourselves in a world without innovation. There would be no R&D and the proverbial GDP pie would start to shrink, meaning governments would have to rely much more on redistribution. A no-growth world would be incredibly challenging to the key pil lars of our society: healthcare, education and the environment. In a world where people are living hand-to-mouth and are chal lenged in terms of opportunities for progress, our ability to re duce political clashes and factions would also be reduced.

Nobody wants to get to that point, and as a result, leaders should be focused on three key drivers of economic growth. The fist is capital, such as infrastructure. The U.S. is currently graded D+ by the American Society of Civil Engineers. That is not good enough. We need roads, we need digitization, and we need ports and airports to drive economic growth. The fact that capital is currently weak and declining works against this.

The second aspect is human capital, both in terms of the quality and the quantity of labour in the workforce. Without investments in quality education, we will continue to see a drag on growth. The third aspect is productivity, which explains about

As protectionism takes hold, employers will face hurdles recruiting staff from the global talent pool.

60 per cent of why one country grows while another does not. Over the last 10 years, we’ve seen productivity decline across many economies — particularly developed ones, but also devel oping ones.

Given the amount and quality of technology we now have access to, this last aspect is a puzzle. If you think about it, produc tivity is just ‘how much output you can produce’ — and we should be able to produce signifiantly more in an era of advanced tech nology. Yet we have seen an enormous drag on productivity.

All three of these engines of growth need to be fiing on all cylinders in order to drive growth. Our public policy and private sector leaders need to be investing with these three drivers in mind in order to support and drive global growth in the years ahead.

Despite this rather gloomy scenario, you believe fortunes will still be made. How?

First, investors and asset allocators need to sharpen their exist ing portfolios and skew allocations to company stocks that will benefitin a more deglobalized world (and remove stocks that will struggle in this environment). Second, they should scale back al locations to geographic regions that depend on globalization, and therefore will be economically challenged in a more siloed world — in particular, emerging markets. And third, they should gain exposure to regions that will excel even in a deglobalized world — such as the U.S. and China, (although the latter to a lesser degree, given its dependence on food and mineral imports.)

In sum, those who are picking stocks need to ask how those stocks will react to the weakening of each of the five pillars of globalization I touched on earlier. For example, with respect to rising trade protectionism, what are the impacts of broken-down supply chains and the growing scrutiny around where a company produces and sells its goods?

Another aspect to portfolio shaping is a more thematic real location of capital, away from areas predisposed to benefitfrom

globalization. In this light, the emerging market (EM) asset class is a signifiant exposure to reconsider because developing mar kets usually have relied on the pillars of globalization for growth, including FDI and trade. Unsurprisingly, EM fundamentals were already weakening prior to the pandemic. In 2020, Brazil’s GDP contracted by three per cent; South Africa’s by eight per cent; and Russia’s by six per cent. Overall, the MSCI Emerging Market Index has returned annualized average returns of just 2.5 per cent compared with the 13.6 per cent average of the S&P 500 since the start of 2010.

You believe investors should embrace three opportunities in particular. What are they?

I take a very simple approach to this: What do I know will be true in the next 50 years? One thing I know for certain is that China is going to be a big part of the global growth recovery. This is an economy that was the largest in the world a couple of centuries ago. It made mistakes along the way, but it is back on track now, with signifiant government support and strong infrastructure, including investments in digitization. According to JP Morgan Asset Management, China’s equities are projected to deliver close to double-digit annual returns over the next 10 to 15 years.

As a sidebar, U.S. pension funds and portfolio managers only have about two-per-cent exposure to China. China today is where the U.S. was in 1950, with respect to having an array of eco nomic profitto come in terms of its population size, government support and ongoing economic growth.

The second major area of opportunity is not surprising: technology. We have seen technology do miraculous things al ready in terms of how we engage in social platforms and how consumers shop, with the dominance of companies like Amazon and JD.com out of China. But we have yet to see the fullscale throttle of what technology can do to disrupt and enhance the delivery and quality of public goods like healthcare and education. There is a lot of effort in the pipeline at the moment

that has yet to materialize. The ability to generate vaccines like Pfize-Biontech is just one example of what is possible here. Going forward, technology in the realm of public goods is going to be an enormous piece of the puzzle with respect to economic growth.

The third area investors need to pay close attention to is the energy transition. Today, even with all the progress that has been made in the last few decades, there are still 1.5 billion people on the planet without access to cost-effective and reliable energy. This is a huge drag on economic progress — and human progress more generally. I believe the investments and innova tion that will occur around the energy transition and fighting climate change will be truly transformative in the years to come. I fully expect to see enormous returns in this arena.

You have warned of the emerging threat of a ‘splinternet’. Please explain.

This is the idea that over the next 10 years, we are going to have two competing technology platforms: One led by the U.S., which is the one we all rely on today, and another led by China. If this materializes, it will impact how companies and individuals com municate, how we transfer money, and how we think about tech nology in general. If your company operates in both the U.S. and China, for example, you will have no choice but to work with two completely different technology platforms.

On that note, Chinese corporate profis could rise by 18.8 per cent in 2021——up from 10.5 per cent in 2020——while Western firms’ growth will pale in comparison. How has China achieved this in the midst of a pandemic?

There are two aspects driving this amazing uptick in multiples and attraction towards the Chinese market. First, its population is becoming more educated and it is increasingly consumerbased, demanding all manner of goods and services — much like consumers in the West. At the same time, people are also looking

for reliable food and water, they’re seeking energy solutions, and Chinese companies are looking for minerals. They’re building houses and plumbing and road networks, and everyone wants access to reliable telecommunications and phones. There will be a huge demand for goods and services of all types in China going forward.

The other issue is government support. Like the U.S. govern ment in the 1950s, the Chinese government is a key driver of the country’ economic success. It is making enormous bets on tech nology, and it has been a big supporter of real estate as well as its many state-owned enterprises. China remains best positioned to survive and thrive in a globalized world — more so than most emerging and even developed-market economies. In this regard, investing in China can be seen as an antidote to deglobalization.

Looking ahead, you believe the risk of a K-shaped recovery is rising. Please explain. Much has been said about the possible alphabet soup of eco nomic recovery post-COVID: will it be L, U, V or W-shaped? Rel atively little attention has been paid to the threat of a K-shaped recovery — one that would exacerbate inequality — and how the private sector can combat this.

Corporate leaders and investors are being called upon to halt the increase in inequality and to take steps to reverse it. There are three things they should consider: Managing an orderly transi tion to automation and the new division of labour between hu mans and machines; improving worker terms and conditions; and allocating capital in ways that are aligned with broader soci etal goals and long-term sustainable growth.

Going forward, you believe corporations need to take mean ingful action in areas that have conventionally been under the purview of government. Ideally, how will this unfold?

It is already unfolding. If you look back to 10 years ago, there was a very clear delineation between what companies did and

We are in the midst of an existential crisis for corporations: Either they fall in line with these new demands, or they will cease to exist.

what governments did: Corporations were focused on achieving shareholder value and delivering their goods and services. Any thing they did in terms of corporate social responsibility was seen as quite separate from that.

Over the past decade, we have seen a push to integrate a lot of those social initiatives within organizations. Education, sensi tivities around race and gender, concerns about the climate — all are becoming part and parcel of how companies do business on a day-to-day basis. For example, corporations can (and should) work with under-represented and minority communities, not only by ramping up efforts to recruit them and offer scholarships, but also by prioritizing efforts to diversify their suppliers, pension advisors and the legal and accounting firmsthat support their op erations.

This is an evolving area, but the cultural frontier for corpora tions is definiely changing. Companies are increasingly making decisions in areas from data privacy to gun control. Even when government does not explicitly opine through public policy, we are seeing business leaders step up and make decisions to out right ban the production or sale of certain products or take ag gressive stances around hiring.

Are you optimistic that leaders can handle this massive chal lenge?

Frankly, they don’t have an option. We are in the midst of an ex istential crisis for corporations: Either they fall in line with these new demands, or they will cease to exist. Everyone from regula tors to employees to worker advocacy groups to customers and investors are demanding these changes.

The notion that companies are only responsible for their shareholders has become archaic. This was confirmedby the Business Roundtable’s statement in 2019 that “companies should serve not only their shareholders, but also deliver value to their customers, invest in employees, deal fairly with suppliers and support the communities in which they operate.” I strongly

believe that this will continue to be the fundamental view ex pressed by a wide range of stakeholders — including investors. If this pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that we all have a vested interest in ensuring society continues to progress.

Dambisa Moyo is an economist and best-selling author who sits on the boards of 3M and Chevron Corporation and has been named to TIME magazine’s list of the 100 Most Influential People in the World. Her fifth anad atest book is How Boards Work: And How They Can Work Better in a Chaotic World (Basic Books, 2021).

Before your imagination can be harnessed, it must be ignited. Strengthening your capacity to see, comprehend and interpret surprises will set you on the path.

by Martin Reeves and Jack FullerEVERY IMAGINATIVE EFFORT BEGINS with a mental spark. Financial pi oneer Omar Selim’s spark came from an unexpected source: his teenage children. Selim, who was Barclays head of global mar kets for institutional clients at the time, was preparing for a trip the following day to Johannesburg. At dinner, he and his children talked about work and life, what matters and what doesn’t. “Okay, so you’re going to flythere tomorrow, stay in a five-star hotel, give a speech, which probably nobody really cares about,” they said. “And this is the path you’ve chosen to dedicate your life to?”

As Selim told us, this blunt exchange with his children actu ally triggered his imagination, throwing everything into question. And this trigger coincided with a situation at work that gave him a lot of time to think. Barclays had sold its investment manage ment arm to BlackRock, with a non-compete agreement, which meant that Selim and his team, who remained at Barclays, were not allowed to do any asset management.

Selim read and thought deeply about sustainability and how

finane might be transformed by non-financialdata and machine learning. Catalyzed by the conversation with his children, he re thought the institution he wanted to work for, putting together a mental model for a new kind of asset management business. Eventually, he set up Arabesque, the world’s fist asset manage ment firmdriven by artificialintelligence and environmental, social and governance metrics.

In this article we will share some insights for sparking your own imagination and that of your team, putting your organiza tion on the path to value creation.

Small surprises — like receiving an unexpected e-mail — hap pen all the time. But the surprises relevant to imagination are the ones that seduce us away from routine thinking and lead us to rethink deeply and inventively. In particular, three types of sur prises can inspire imagination:

ACCIDENTS events or consequences that are incidental or irrel evant to what we are trying to achieve;

ANOMALIES — parts of a situation, story or dataset that are out of the ordinary; and

ANALOGIES — parallels we notice between concepts or experienc es, which suggest new possibilities.

However, for any of these types of surprises to impact us, our minds must be prepared. Plenty of things pass us by every day, but to spark imagination we need to notice them (the cogni tive aspect) and care about them (the emotional aspect). If Selim had not cared about reforming finane, he wouldn’t have started Arabesque. Equally, if he had not noticed how machine learning was impacting other businesses, he would not have had a stock of mental models to draw on in rethinking how an asset manage ment fim could work. The more we commit to caring and no ticing, the more we create the mental context for encountering imagination-provoking surprise.

There are two key manifestations of caring: via aggravations or aspirations. Aggravations or frustrations drive us to change or escape from something, while aspirations drive us to bring some thing we want or believe in into being. Aggravations and aspira tions can enable us to notice things on three levels: by seeing, comprehending and interpreting. Let’s take a closer look at each.

STAGE 1: Seeing

Seeing entails taking in new information. If we don’t do this, we won’t encounter any kind of surprise. If we’re stuck doing only routine things every day, not having interesting conversations or exposing ourselves to new social or geographical environments, we get stuck in ‘informational oblivion’. Following are three ac tions related to seeing that can help you use your imagination more frequently.

MAKE TIME FOR REFLECTION. Given the amount of pressure they face, business leaders need to work hard to protect time for re flection. Inspiration for imagination often comes when we are reflecting: relaxing, with no pressure from urgent tasks.

It may be no accident that people often get inspired in the bath or shower, because they tend to dampen our figh-or-flight nervous system in favour of the ‘rest-and-digest system’. Omar Selim told us that inspiration often happens for him in this con text: “I get most of my ideas while showering in the morning. I feel inspired when the temperature around me is just right; I relax and I’m not bothered by anything.”

In the early days of Merrill Lynch, founder Charles Merrill wrote to his business partner Winthrop Smith about the impor tance of taking time to reflect: “You and George Hyslop [a partner in the fir] and I should never be so busy that we can’t set aside at least one hour each day to quiet, thoughtful study and discussion of our basic principles, as contrasted with current operations.”

Imagination requires blocks of time with low external de mands. Warren Buffett famously schedules time for a ‘haircut’ in his diary, which is actually code for him to sit in a room and reflect. We need time to think about our aspirations and aggrava tions and follow our curiosity rather than a deadline. Some ways to do this include:

• Taking a few deep breaths in and a few longer breaths out

• Taking time over a meal to rest, mentally digest and reflect

• Listening to or playing music

• Going for a walk without your phone

PAY ATTENTION TO FRUSTRATIONS. If they don’t emotionally over whelm us, aggravations or frustrations can help us care about what we notice. In 2008, MBA student Shelby Clark was cycling to pick up a Zipcar he had rented. As he told us: “I got stuck in a snowstorm. I was biking through the snow, grumbling the whole way, thinking: ‘Why am I passing all these parked cars, to get to a car? Why can’t I get in that car? Or that car?’”

This was the imagination-triggering event for Clark. A row of unused, parked cars wouldn’t surprise most of us. But driven by his frustration, it stood out for him, prompting him to chal lenge the existing mental model of private transportation and kicking offcounterfactual thinking that led him to found Turo, the world’s fist private-car-sharing company.

The idea for genetic testing company 23andMe was also inspired by frustration. Founder Anne Wojcicki had spent 10 years working in healthcare investing. At a conference about in surance reimbursement, she remembers thinking: All these peo ple are here just to figue out how to optimize billing. “I realized, I’m done. At that moment it became clear that the system is never going to change from within.”

This frustration was a potent emotion, but it took a triggering event for Wojcicki to come up with a better alternative. “There was a very specificevent where I was at a dinner with a scientist,” she recalled. “We were saying, ‘Theoretically, if you had all the world’s data and genetic information, couldn’t you solve a lot of problems?’ And the conclusion was yes — you could revolutionize healthcare.”

By taking our frustrations seriously, we prepare our minds to imagine our way out of them.

This conversation inspired her to begin imagining a new business, a path that eventually led to a genetic testing company with a multibillion-dollar valuation. By taking our aggravations seriously, we prepare our minds to imagine our way out of frus trations.

ENGAGE WITH OTHERNESS. To engender surprise, you not only have to care, you have to be in a position to notice imagination-pro voking things. The most basic way to do this is to get out of the (metaphorical) house and seek the unfamiliar.

As a company grows, more mental space gets taken up with internal requirements: ‘What should I say to the board?’ ‘How should I write this review?’ Like a sphere, the volume of a growing corporation grows faster than the area exposed on the surface. On the inside, familiar processes and scripts come to dominate, shielding us from unexpected and potentially inspiring external interactions.

University of Chicago Sociologist Ronald Burt studied the origins of ideas within companies and found that people who had more exposure to the outside had better ideas. When his study asked inward-facing managers at an electronics company for their ideas, they often produced the “classic lament from bureaucrats: ‘we need people to adhere more consistently to agreed-upon processes.’” In contrast, what might seem to be a routine role produced imaginative thinking: “Better ideas came from the purchasing managers, whose work brought them into contact with other companies.”

Selim of Arabesque described how he tries to break his team’s routines while travelling, to seek encounters that might prompt imagination: We all fly economy and take public transport in diffrent coun tries. Not to save money, but to get out there and have some chance encounters — sitting next to a lady on the train in India who is going to talk to you about her kids, or whatever it may be. When I’m visiting a new city, I always try to find a meal for un der $10. It takes me to some fascinating places and gets my mind working — dealing with places, people, or ways of doing things that are not what I see every day. This often sparks new thoughts.

STAGE 2: Comprehending

Comprehending demands processing something we see to un derstand it. We might be exposed to new information, but unless we say, “Wait, that is an interesting anomaly. Let’s think about that,” or “Why do you think we got that accidental result? Isn’t that curious?” then we are not using our brains. If we don’t put

in the time or effort to process what we see, we are in ‘computa tional oblivion’. Following are two ways to enhance your ability to comprehend surprises.

REFLECT ON ACCIDENTS. Accidents are the incidental results of our actions or things we bump into while trying to do something else. These are the surprises that come out of left fild, unrelated to the mental model we are working with.

Tim O’Reilly, founder of O’Reilly Media and a leading thinker in Silicon Valley, emphasized to us the importance of be ing open to what might arrive from outside your mental model: “Think of imagination as a process of letting go of what you know, experiencing life fresh. The world is infinie. We experi ence only part of what is out there, and then, we attach labels to our experience. But people get stuck on the labels.”

The classic business example of this is the story of Viagra. Originally developed as a heart medication by Pfize , research ers noticed a side effect in a completely different area of the body. This would have been easy to dismiss as a useless side effect, giv en that the researchers’ minds were focused on heart conditions. However, they thought about the accident and connected it with an aspiration from a different medical fild: addressing erectile problems. They allowed themselves to be led down this unex pected path, and Viagra eventually became one of Pfier’s most successful products.

INVESTIGATE ANOMALIES. If an accident is something outside the mental model you are working with, an anomaly is a violation of the expectations that a familiar mental model is giving you. It takes effort to notice this dissonance, to realize that the explana tions your mental model suggests are misleading or wrong. As philosopher John Armstrong noted to us: “We’re actually quite slow to notice new pieces of information. We’re invested in the models we currently have — of a company, of another person or of how things work. And that emotional familiarity is something we can be very reluctant to give up.”

One example of successful anomaly investigation comes from a Boston Consulting Group (BCG) project with a U.S. company that makes diagnostic machines for hospitals. The prevailing mental model of this business was to invest in sales people and save money on technicians. During the project, one executive noticed that the company was selling more machines in Manhattan. This was a crucial moment. It would have been possible to see this but resort to the explanation from the pre vailing mental model: The sales team there must be better.

However, the leaders pushed further, and in digging deeper, they discovered an additional anomaly: Manhattan was the only re gion that assigned on-site technicians. The reason for this was that managers didn’t want engineers wasting paid hours in New York traffi it was more efficiento appoint on-site engineers.

The surprise in this case came from connecting the two anomalies. As the team noted, “Constant contact with the tech nician bred close relationships with the users of the equipment, and the service engineers developed an in-depth understanding of customer needs. Technicians had become the company’s most productive salespeople.”

This surprise kicked offmuch counterfactual thinking. The leaders imagined a new business model with technicians at the centre. They invested in data gathering from technicians and lines of communication between sales and engineering. It as signed on-site engineers elsewhere. The result was an additional eight points of market share and a boost to its margins of 25 per cent. We are used to pattern recognition, but the skill of anomaly (or pattern-break) recognition is just as important in business.

The deepest stage of noticing, interpreting entails connecting — noticing the ramifications of one piece of information for oth ers. Think of the difference between you and a trained biologist walking through a forest. Where you see simply a leaf, they notice

the early appearance of a rare tree at an unusual elevation, imply ing a changing climate, which has implications for the forest as a whole. Their biological worldview allows them to make more connections. If we can’t draw on a rich conceptual inner world made up of deep and varied worldviews, we are in ‘conceptual oblivion’.

Following are two ways to increase your ability to interpret what you see and comprehend.

DRAW ANALOGIES. Drawing analogies entails taking some element you have comprehended in one area and importing it into an other. Using analogies can be a powerful trigger for imagination in business. As noted earlier, the inspiration for car-sharing com pany Turo came when Shelby Clark drew an analogy:

I had just come out of a really amazing meeting at Kiva, a peerto-peer microfinance lending platform, when I made a mental connection between Kiva and Zipcar. It came together quickly in my head: The limitation of Zipcar was that there weren’t enough cars. Whereas in reality, especially in America, we have a lot of cars. There is no shortage of cars. The problem is that we don’t use them well. So a peer-to-peer marketplace would bring people together and solve that problem.

Venture capitalist Bill Janeway also kick-started his imagina tion with an analogy during the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s. As he said, “I wrote my PhD thesis on the stock market between 1929 and 1931. So in 1999, I had in my mind that stock price chart of RCA between 1926 and ’32 — and if you put that next to the stock price chart of Veritas between 1996 and ’02, they are identical.” He told us that seeing this analogy triggered him to adjust his mental model of what could lie ahead and to anticipate the burst of the dot-com bubble.

To ‘mine’ an analogy, use the following process:

STEP 1: CONNECT. Identify mental models connected to what you are considering. To draw this connection, describe the features of what you are considering in a more general way. For example,

Never (1)

Rarely or less than once a year

(2)

Sometimes or once a month to once a year

(3)

Usually or once a week to once a month (4)

Always or more often than weekly (5)

Employees at our firm mae time for quiet reflection

People in our firm find inventive ways to address problems and frustrations.

The business gives employees regular opportunities to encounter enriching, thought-provoking things outside the firm and its regular clients.

Employees notice, report and discuss interesting accidental or unexpected outcomes of initiatives or analysis.

If people in our firm find an unexpected opportunity, they explore how to act on it.

Our business regularly looks for and analyzes anomalies in granular data.

People in our firm use surprising analogies and perspectives in presentations.

Related Action

Make time for reflection

Pay attention to frustrations

Engage with others

Reflect o accidents

Reflect o accidents

Investigate anomalies Draw on analogies

Total

After you have added up your total, score your current situation: 31-35, excellent; 21-30, good; 11-20, moderate; 0-10, poor.

FIGURE TWO

say you are looking for analogies around real estate agents. Real estate agents help people choose houses. This is one instance of the general idea of giving guidance. To findinteresting connec tions, ask: Where else does giving guidance occur? Counselling, advice columns, IKEA furniture manuals, teaching, and so on.

STEP 2: SELECT. Choose a concept from a new mental model to im port. For example, you might select the concept of emotional un derstanding from counselling (that counsellors learn the unique psychology of their clients). Or the concept of mentoring from teaching (that teachers relate to their students over time to help them develop).

STEP 3: INJECT. Now explore injecting this foreign concept into the mental model of the original thing. Asking ‘what if’ ques tions can help prompt your imagination here. What if real es tate agents became like counsellors in terms of understanding the emotions of their clients? What if estate agents became like

mentors, helping us develop our homes?

Going through this process can offer surprising suggestions that inspire us to start thinking imaginatively, exploring mental models of things that do not yet exist.

LEARN NEW WORLDVIEWS. To increase surprise, you can also learn new worldviews: systems of concepts and mental models that provide different ways of interpreting the world. New world views can create surprise when brought up against familiar information. For example, if you hired the manager of a For mula One technical crew for your logistics team, they might make some interesting observations because they notice things through the lens of high-intensity racing.

Janeway argues for the value of humanities-based world views, from philosophy, history and literature, to enrich the busi ness mind. By living mentally in alternative worlds — scholastic debates in medieval Europe, the life of an aristocrat in 19thcentury South America, or philosophical thought experiments —

he believes we can see with a deeper understanding, allowing us to notice more patterns and anomalies. As he told us:

We can learn a lot about the emotional elements of financial market behaviour from the humanities. A prime example is Anthony Trollope’s classic novel, The Way We Live Now It traces an extreme speculative bubble on the London Stock Exchange in the 1870s, promoted by a plausible con man and driven by waves of investors drawn into the fraud until — ulti mately and necessarily — the bubble bursts. Our recent history replicates the phenomenon with extraordinary precision, from Enron through Theranos and on to Wirecard.

Janeway reflected on his humanities education: “I think this background has given me a number of really unfair benefitsand advantages as an investor: to be able to have useful, speculative conversations, assess unusual ideas, think about alternative fu tures.”

Our advice: Pick a few new worldviews to immerse yourself in. They could be from different disciplines, like Engineering, Theology or Psychology; from writers with distinctive ways of seeing, like authors of science fictionor heroic novels; or from distant places or times that had ways of interpreting that seem strange to us. The point is to enrich your stock of worldviews to draw upon when observing.

At the root of all innovation lies imagination. Corporations have harnessed it to change the world radically in many areas: medicine, consumer goods, transport, finane, agriculture, en tertainment, communications. As indicated herein, exercising imagination is not only about individual creativity; it is also about how minds can interact, creating collective imagination and momentum to turn ideas into new realities. And today, we need organizational leaders to embrace this challenge more than ever.

I was doing a trade, and something didn’t feel quite right about it.” , who was work-

time, told me. “It turned out I had lost on the order of tens of thousands of dollars, which wasn’t a huge amount of money for

The thing is, it was something only Chris knew about. What would you do next? Pretend nothing happened and hope no one noticed? Blame someone else? “After a little while, I went to my manager and brought his attention to it.” Chris owned up to his mistake and then waited for the other shoe to drop. That’s not what happened.

“I received feedback from a number of very senior pened. They came up to me and said, ‘Hey, it’s so great you were open about your mistake.’ I have never received more praise in my life.” When Chris admitted his costly mistake and his bosses thanked him for it, both employee and employer came out of it in a better place. “It totally cemented my belief in that form of open, honest culture.”

That isn’t always how things play out. The challenge for leaders is to make an experience like Chris’s the norm. It’s not just about changing the way we view mistakes. There is a larger challenge here: How do you create a culture for em-

ployees that is psychologically safe?

Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmondson coined the term. When I spoke to her recently, she explained: “Psychological safety is the belief that you can bring your full self to work. Quite simply, it’s the perception that you can speak up with ideas, questions and concerns, or ask for help and people won’t embarrass you for it.”

There are two key components of psychological safety, she says: respect and trust. “Trust is the belief that someone has your back and won’t act in a way that harms you. And respect is the appreciation for who someone is.” Amy is re-

know the core elements of successful medical teams. making the fewest mistakes. But the data showed that the better-performing teams reported actually more mistakes, not fewer. “The more I thought about it, the more it occurred to me that maybe better teams don’t just make more mistakes, they’re more willing to talk about them, for the express purpose of catching and correcting future mistakes before anyone is harmed.”

With actual lives at risk, the importance of fostering this kind of open communication may seem obvious, but how vitech company?

This was something Google years ago when it launched Project Aristotle — a massive study of 180 of its own teams to determine the key elements of really successful teams. is a people scientist who worked there at the time. “In the beginning, people expected that it was about team composition. They thought an algorithm for the perfect team might be, ‘get an engineer, a PhD, some diversity of gender and race, and voila: the perfect team’.”

didn’t matter as much as how the team operated. Psycholog-

not afraid to make a mistake, the team can learn. And learning is what ultimately leads to high performance over time.”

response had been, ‘I can’t believe you made that mistake; don’t ever do that again’,” he never would have shared another mistake or concern. That early positive experience really stuck with him. No longer a trader, Chris is now a consultant and speaker. He co-authored a book with Rotman School Professor Andràs Tilcsik called Meltdown: Why Our Systems Fail and What We Can Do About It , about open communication.

If being transparent with each other at work can do this much good, colleagues develop a mutual sense of trust

performing team, why isn’t psychological safety happening everywhere, all the time? Because people are complicated For prehistoric humans, survival depended on developing strong social bonds and sticking together in groups for safety and shared resources like food and shelter. To this day, that motivates us to behave in line with what the group expects and try to maintain status by coming across as competent and reliable. It’s also one of the reasons why we don’t always communicate openly about problems or concerns.

Edmondson says this fear goes beyond not just being able to deal with mistakes. “It turns out that interpersonal

hija c k’: Wh en the amygdala gets tr ig ger ed, we freeze. We’re not going to say, ‘Oh, look, I made a mistake. I need help’. We default to hiding those things because we’re afraid. And it literally narrows our brain’s ability to engage in analytic thinking and problem solving.”

“Teams that have low psychological safety are much

vulnerable at work. “That stance of, ‘I know what I’m doing’, even if you don’t, you can get away with for a while in your career. But you will get to a point where the problem is hard enough and it involves so many other people that you can no

It isn’t just our own fears that we need to address; we also have to navigate the threat and fear responses of every other person on our team. Individual employees aren’t exactly sitting around discussing how to up their psychological safety game. But there are things you can do to help lay the groundwork for a culture of healthy communication.

“The power of any given individual in helping alter the work environment, I think, is very great,” says Edmondson. One of the simple things that anyone can do is ask their colleagues a genuine question. For example, ‘What thoughts do you have about this project?’ “That’s not a yes or no question — it gives people room to respond. The beauty of asking a good question is that in that moment, you are automatically giving people a small, safe space to respond. You have explicitly said, ‘I’m interested in what you have to say ’.”

Psychological safety also requires humility. “Anytime someone genuinely says, ‘I don’t know’, it makes the world a tiny bit more psychologically safe for others. That phrase is an expression of vulnerability, and by saying it, you’re inherently giving other people permission to say it, as well.”

As you try to change the way you relate to your colleagues, it’s also a good idea to check in on how you relate

safety. Kim Scott explains how to build healthy work relationships in her book, Radical Candor: How to Get What You Want by Saying What You Mean

radical candor with someone who has the power to not pay you a bonus or to fire you,” she says.

What exactly is radical candor? “When you show some one that you care about them, and at the same time, you challenge them directly when you see them making a mis take, that’s radical candor,” she says. It’s about communicat ing honestly, but in an empathetic way. It’s about challeng ing directly, which is the honesty part, and caring personally, which is the empathy part.

The tricky thing, Scott says, is that you really need to take time to gauge how your message is landing for the other person and be ready to adjust. “This requires active listen ing, kindness and some emotional intelligence, which is the ability to look for and understand someone’s emotional state — while still challenging directly with specific feedback.”

Scott says 85 per cent of our radical candour mistakes occur when we show that we care personally, but we’re so concerned about not hurting someone’s feelings, we fail to tell them something they’d be better offknowing. She calls this ‘ruinous empathy’, and it happens when our desire not to hurt the other person’s feelings stops us from speaking up about something that need to change. The problem is, who ever it was that needed that feedback misses out on the op portunity to learn something.

What if someone gives you feedback, but you don’t agree with it? How do you respond without alienating your co-worker or boss?

“First of all, whatever the person said, you can prob ably agree with at least five per cent of it. So focus on that five per cent and say, ‘I totally agree with that and I’m go ing to work on it’. Then say, ‘As for the rest of it, I need to think more about it. Is it okay if I get back to you?’ Then, you must get back to them within a day or two and offer a reasonable explanation for why you disagree — especially if this is someone you work with regularly.”

Believe it or not, bosses are often afraid of their em ployees, says Scott. “They’re afraid to say what they really think, because they’re afraid they’ll demoralize people or that they’ll quit.” Getting everyone on the same page with radical candor can be increasingly challenging as compa

nies become more and more diverse across gender, race, age and many other demographic lines. The people you work for and with may not understand your identity or your lived experience, and you might not understand theirs. And that lack of understanding can lead to a lot of silence on both ends.

As much as you can practice the personal elements of psychological safety, beyond a certain point, it’ll be diffilt to change the larger organizational culture if your boss isn’t invested in the same thing.

Edmondson notes that one can, and should, ask things like, ‘How will I be able to contribute to this project? Are you interested in me bringing in new ideas?’ She also recom mends asking for stories of how people in the organization have made a positive difference in the past and changed how things unfolded in some way. “And if there are no stories like that for people to tell,” she notes, “you might want to run for the hills.”

Sonia Kang is the Canada Research Chair in Identity, Diversity and Inclusion at the University of Toronto and Associate Professor of Organizational Behaviour and HR Management at the University of Toronto Mississauga, with a cross-appointment to the Rotman School of Management. She is U of T Mississauga’s special adviser on anti-racism and equity. This article has been adapted from her podcast, For the Love of Work, which is made possible by Rogers and is available wherever podcasts are heard.

‘Ruinous empathy’ happens when our desire not to hurt another person’s feelings stops us from speaking up.

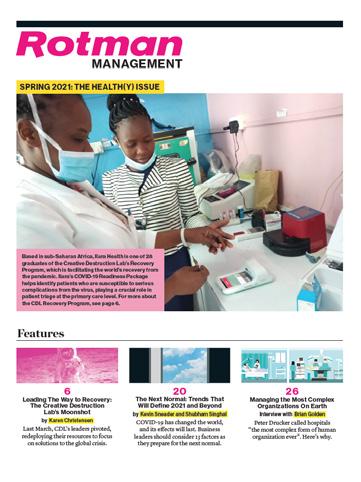

Last March, it became clear to CDL leaders that honouring their mission would mean redeploying their resources to focus on the global crisis.

by Karen ChristensenIMAGINE A WORLD where a wristband alerts industrial workers whenever someone is less than two metres away from them; where a pay-as-you-go app for small medical providers in subSaharan Africa identifis patients who are susceptible to serious COVID-19 complications; and where modular off-grid facilities can be rapidly deployed for housing, health and educational purposes anywhere in the world.

You don’t have to imagine such a world, thanks to the Cre ative Destruction Lab (CDL).

“Novel crises require novel responses, and novel responses require innovation — often predicated on insights from sci ence.” That according to CDL founder Ajay Agrawal, who is the Geoffey Taber Chair in Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the Rotman School of Management and whose team has been on the front lines of developing solutions to help the world recover from COVID-19.

CDL’s stated mission — pre-pandemic — was “to accelerate the commercialization of science for the betterment of human kind.” And it was well on its way when COVID-19 shut down most of the world last March. “In the early days of the pandemic,

it occurred to us that honouring our mission would mean rede ploying our resources to focus on this global crisis by applying the CDL model and community to rapidly translate science into solutions,” he says.

What CDL does well — arguably better than anyone else — is accelerate the commercialization of new ideas. And with the fist global pandemic in a century on the horizon, the world sorely needed them. “With COVID-19, we had a novel crisis on our hands that nobody had faced before,” says Agrawal. “Ex perts in Public Health had seen pandemics before, but not with such a broad economic impact. Suddenly, we were faced with a problem that nobody knew how to solve.”

CDL had been designed to take ideas — many of which emerge from university labs around the world — and commer cialize them. A team of scientists in Toronto or San Francisco would come up with an innovation with commercial potential, but they had no idea how to turn it into a product. Enter CDL. Through its network of mentors — some of the world’s most successful tech entrepreneurs, inventors, scientists and investors — it provides the support required to bring the product to market.