Contents

Departments

RISD News

Tina Weymouth 74 PT and Grandmaster Flash, At the Museum, RISD video games, RISD CATALYST and AI Poetry

The Smithsonian acquires work by Jennifer Judkins 08 PH

Brian Selznick 88 IL talks about Big Tree and Steven Spielberg’s inspiration

Guggenheim Fellows Christina Seely MFA 03 PH and Claudia Bitrán MFA 13 PT

Class Notes

On the Street: James Carpenter 72 IL and the 57th Street Facade

On the cover This page

A contemporary rendition of a 19th-century specimen table top, the Gyro uses “ocean terrazzo,” an innovative material produced by fragments of ocean waste, to depict the earth’s longitudinal and latitudinal lines.

Photo by Angela Moore.

The E-Turn bench refers to eternity and explores the possibility of a singular line morphing and twisting dramatically, transcending width and dimension. The piece was highlighted by Time magazine’s The Design 100.

Photo by Angela Moore.

Features

Let’s Eat

Daniel Pelosi 05 IA, or @grossypelosi, talks about the secret sauce that has launched his new career in the food space.

Form and Function

An interview with furniture maker and activist Brodie Neill MFA 04 FD

State of Flux

Ilana Savdie 08 IL has a new exhibit of paintings at the Whitney Museum, work that dazzles, beguiles and refuses to stay put.

90s Art School

An analog-to-digital archive of Polaroids curated by Matthew Atkatz 97 ID documents art school in the 1990s.

President’s Letter

We are grateful to our alumni groups around the world for their active and enthusiastic engagement. Your eagerness to participate becomes a source for building the infrastructure that has helped start new alumni clubs and the sustenance that strengthens existing groups.

In May, we welcomed Dallas Pride as the new Executive Director of Alumni + Family Relations. We are thrilled to have her steward a vision for facilitating engagement among our alumni clubs, and for her and her team to serve as conduits for the work alumni want to see accomplished. An example of which will be organizing RISD’s first Black alumni reunion, an idea championed and spearheaded by the Black Alumni Affinity Group. We are excited to see what ideas are realized next!

Examples of community-centered alumni engagement have run across the entire year and continue into the fall! This spring, for example, we were fortunate to host Adam Silverman BArch 88 at the RISD Museum and experience his Common Ground installation, where we enjoyed delicious food served on Adam’s gorgeous wares and reflected on our connections to place, community, the earth and each other. Over the summer, 19 students met with a group of Los Angeles-based alumni to learn about the animation, film and game design industries. I also had an opportunity to connect with Rachel Cope 03 SC, whose customized wallpaper installed at the President’s House is always a conversation starter whenever students, staff, faculty or friends come to visit. Rachel will serve as the inaugural guest curator for a new exhibition space in the President’s House, The Bowen Project Space, which is slated to open in November. And most recently, our alumna Vicky Reynolds, Chief Gemologist and Vice President of Global Marketing–High Jewelry for Tiffany & Co., was on campus with a Tiffany’s Team engaging with our Jewelry and Metalsmithing faculty and students. These are examples of the different and exciting ways in which alumni drive and define “community,” and is one of the things that helps make RISD such a special place.

Adam’s, Rachel’s and Vicky’s fondness for RISD is palpable, and their desire to help others have such a positive experience on campus and in art and design spaces shines through. I am heartened to know that RISD creates space for alumni to return and share their gifts with the campus community through the issues and topics that inspire them. Those spaces of welcome inspire our alumni to share their belief in the power and necessity of art and design, and their love of RISD with others—for Adam it was making a connection between RISD and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston; for Rachel, an offer to curate new gallery spaces at the President’s House; for Vicky it was helping to create a relationship between Tiffany’s and the next generation of jewelers and metalsmiths.

In this issue, read stories about RISD alumni who take this to heart, and who have turned their community-centered attention and intentions back onto RISD. Ilana Savdie 08 IL is exploring issues of social justice, transgression, identity and power in her vibrant, large-scale paintings on view at the Whitney Museum. Dan “Grossy” Pelosi BFA 05 IA built a community in the darkest days of the COVID-19 pandemic by sharing tantalizing images of his home-cooked family recipes on Instagram, and Matt Atkatz 97 ID, through his 90s Art School Project, is fostering digital connections among former RISD students using analogue photography.

We also feature stories on 2023 Guggenheim Fellows Christina Seely MFA 03 PH and Claudia Bitrán MFA 13 PT, and share a story about Jennifer Judkins’ 08 PH search for meaning by chronicling her father's illness in photographs in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks. Our cover story focuses on furniture maker Brodie Neill MFA 04 FD, who stands apart from his contemporaries due to his progressive use of form and his dedication to reclaimed materials.

I hope these stories inspire you to engage more deeply in our community by sharing your passion, making a connection and giving back.

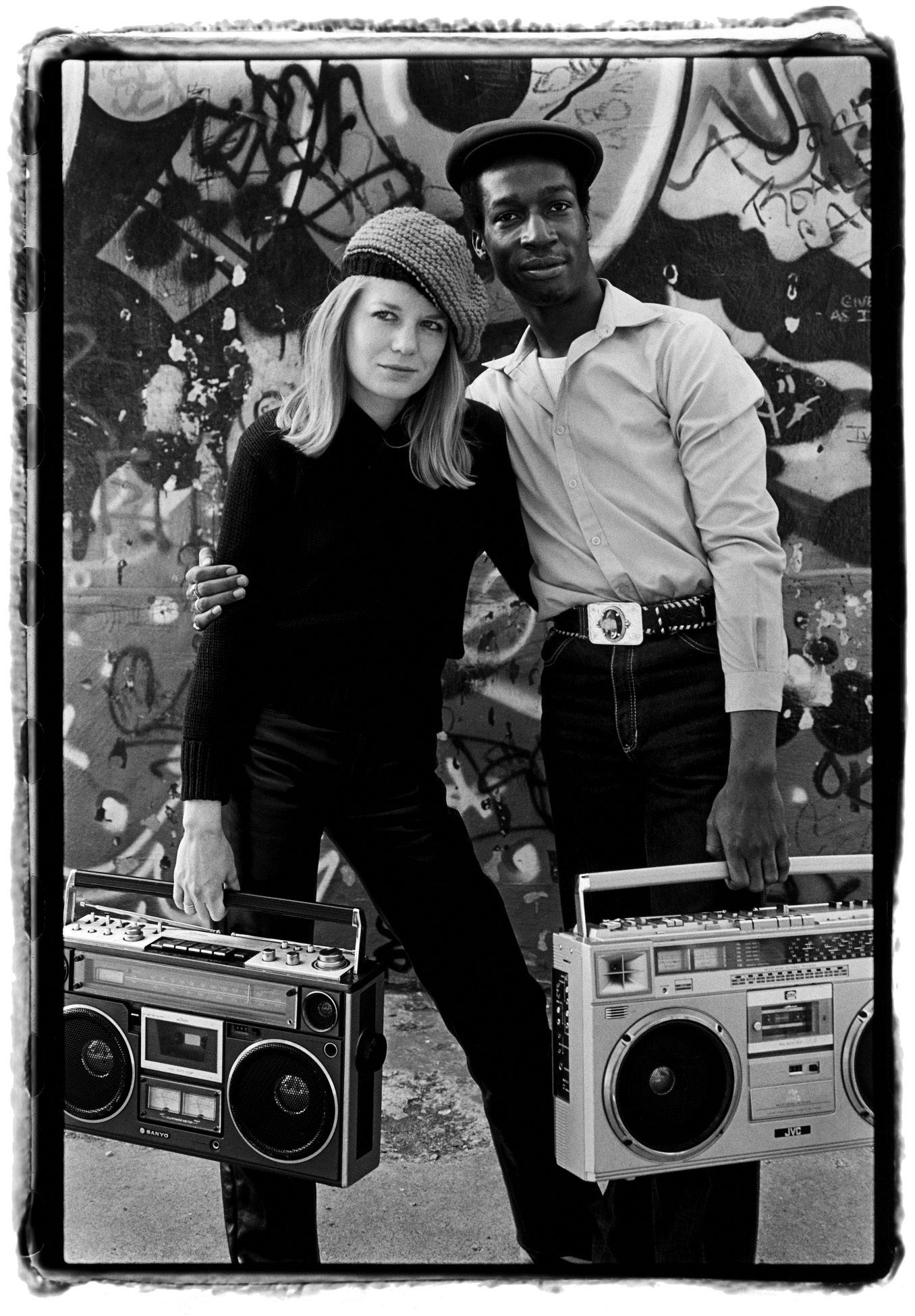

—Crystal Williams, RISD PresidentTina Weymouth and Grandmaster Flash, NYC, 1981

In the next issue of RISD Alumni Magazine

This photo of Tina Weymouth 74 PT and Grandmaster Flash (Joseph Saddler) resides in the National Portrait Gallery. Weymouth and her husband, Chris Frantz 74 PT, were founding members of Talking Heads and Tom Tom Club. Talking Heads, which also included former RISD student David Byrne and Jerry Harrison, reunited at a 40th-anniversary screening

of Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense in September at the Toronto International Film Festival. Filmmaker Spike Lee moderated a post-screening Q&A.

, Weymouth and Frantz will open their archive to share images from their rock ’n’ roll careers.

Photograph by © Laura Levine,

1981, lauralevine.com

This photo of Tina Weymouth 74 PT and Grandmaster Flash (Joseph Saddler) resides in the National Portrait Gallery. Weymouth and her husband, Chris Frantz 74 PT, were founding members of Talking Heads and Tom Tom Club. Talking Heads, which also included former RISD student David Byrne and Jerry Harrison, reunited at a 40th-anniversary screening

of Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense in September at the Toronto International Film Festival. Filmmaker Spike Lee moderated a post-screening Q&A.

, Weymouth and Frantz will open their archive to share images from their rock ’n’ roll careers.

Photograph by © Laura Levine,

1981, lauralevine.com

Peabody Award

RISD alumni win for New Yorker VR documentary.

Among this year’s Peabody Award honorees were Nicholas Rubin 01 FAV and Oliver Carr 20 FAV, who worked on the virtual reality documentary and interactive feature Reeducated for The New Yorker. Rubin was a producer, lead animator and technical supervisor for the documentary. Carr served as assistant animator for the interactive piece.

Reeducated uses first-person accounts, illustration, and traditional and digital animation to take viewers inside the secret world of one of the “reeducation” camps in Xinjiang, China, where Uyghurs and other minorities are being arbitrarily and brutally detained.

Nicholas Rubin’s company, Dirt Empire— whose previous work has included designing projection experiences for Beyoncé and the United Nations and other live events—collaborated with a team of visual effects artists to bring the project into stereoscopic virtual reality over the course of a year. The austere tone of the black-and-white film, which has the feel of a graphic novel, was set by Matt Huynh’s hand-painted illustrations, which

Rubin and his team turned into immersive virtualreality panoramic environments. The process was painstaking.

“It’s one of the most difficult projects I’ve ever worked on,” says Rubin, who wanted the film to look “as analog as humanly possible,” despite the highly technical animation work involved.

The project was also challenging, he says, “because we were communicating real, tragic things that are still happening to people and we wanted to do it respectfully, with accuracy.”

Part of the team made an extra trip to Kazakhstan to share Huynh’s drawings with the three former detainees featured in the film and to get more details—the exact placement of the bunks, the size of the classroom, what the window looked out on, who was in the room, what their meals consisted of.

Reeducated premiered at South by Southwest (SXSW), where it took home a special jury recognition prize for immersive journalism, and has since screened at the Venice Film Festival and dozens of other festivals around the world, as well as winning an Emmy Award in 2022.

Photo courtesy of Nicholas RubinAn Early Accolade

Mochi Lin is short-listed for Yugo BAFTA awards.

When Mochi Lin 22 FAV learned that she had been short-listed for the 2023 Yugo BAFTA Student Awards in the animation category, her first reaction was disbelief. Lin, who created Swallow Flying to the South for her senior-year thesis project, had no idea her professors had nominated the film for the prestigious award. Earning this accolade brings a rewarding sense of closure to the last year, says Lin, whose film has now been shown at more than sixty film festivals.

The story for Lin’s eighteen-minute stop-motion animated film was one she had heard many times at the dinner table while growing up. It’s about her mother, who at the age of five was sent to a boarding preschool in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution. Many years later, Lin’s parents emigrated to Canada, but the story of this lonely period in her mother’s childhood remained vivid.

“Preschool is a really important stage in a person’s life,” says Lin. “It’s the first time a person shifts away from family and it’s the first of many institutions. A lot of people find an inability to fit in and this film is about that.”

Swallow Flying to the South is a tribute to her mother, so Lin was determined to get the details right, everything from the clothes to the look of the chamber pots to the sound of the pigeon whistles and street peddlers of Beijing.

Lin chose stop-motion because she wanted the set to have a tactile quality. Creating the characters, who have three-dimensional bodies and two-dimensional faces, took some experimentation, says Lin, who painted the faces and ultraviolet-printed them onto acrylic. Their movements are limited and mechanical, which is what Lin wanted, since “in the story the children are puppets themselves because they are under their teacher’s control and don’t have much freedom of movement.”

Festival audiences were surprised, Lin says, that she handled every aspect of the film, from music to animation to editing. While that was a challenge, especially in such a short time frame, Lin is grateful for the holistic view of filmmaking it gave her.

“I’m glad I got to experience the whole process. Because this film was so personal, I enjoyed having total control. Now I want to try more collaborations.”

Still from Swallow Flying to the SouthAt RISD Museum

The museum names a new director, and other news.

Tsugumi Maki is the new director of RISD Museum. Most recently with San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), where she served as chief exhibitions and collections officer, Maki brings twenty-five years of experience in the museum field.

“I am thrilled to welcome Tsugumi to RISD,” said RISD President Crystal Williams. “During our search process, I was struck by her expertise, her inclusive and collaborative leadership style, and her deep knowledge and experience at institutions we admire. In addition to extensive experience in the museum field, Tsugumi brings an artist’s eye to her work and a deep appreciation for makers that will be an added benefit to the RISD Museum.”

Maki’s museum career has included leadership roles with the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where she played a key role in developing major expansion projects including the Art of the Americas Wing and the Linde Family Wing galleries.

“I am honored to step into this role,” said Maki. “Our shared goal is to continuously challenge

conventional museum experiences, fostering a space where visitors not only observe art, but actively engage with it. I am excited to collaborate with the incredible RISD team and explore innovative pathways that amplify creativity, inspire learning and nurture an even more inclusive and vibrant community.”

In other museum news, an exhibition of Diné (Navajo) apparel design is on view until September 2024. Diné Textiles: Nizhónígo Hadadít’eh includes wearing blankets, mantas and contemporary art spanning more than 150 years of design, resilience and creativity.

Additionally, photographer and multimedia artist Lorna Simpson spoke at the Gail Silver Lecture on October 11. The first Black woman to exhibit at the Venice Biennale, Simpson rose to prominence in the 1980s and ’90s with photo-text installations that questioned the nature of identity, gender, race, history and representation.

Photo courtesy of RISD Museum

For updated information about museum news and upcoming events, visit risdmuseum.org.

Chief-style blanket by Diné weaver, ca. 1880–1900

Photo courtesy of RISD Museum

For updated information about museum news and upcoming events, visit risdmuseum.org.

Chief-style blanket by Diné weaver, ca. 1880–1900

In the Nature Lab

Students draw on nature to design a more sustainable world.

Jen Bissonnette likes to remind visitors to RISD’s Edna W. Lawrence Nature Lab that biomimicry— taking cues from nature to improve product design— is nothing new. Pointing to a kingfisher perched in a cabinet high up one wall of the Waterman Street space, she notes how Japanese engineers redesigned the front end of the bullet train to mimic the shape of the bird’s beak, making it more aerodynamic.

Increasingly, issues around sustainability are driving the mission and work of the lab. Bissonnette, an ecologist and marine scientist who is the lab’s interim director, wants RISD students to ponder what it means to “not just be inspired by nature but to understand how nature functions and make our work dovetail intentionally with that.”

Everything about the design of the student-built Biodesign Makerspace—from the certified-wood benches to the handmade-paper light shades and living plant wall—is focused on sustainability. Tabletop inlays depict the Narragansett Bay’s waterways, while saltwater tanks house aquatic species found in local bays and canals. Two aquaponic systems

grow lettuce to feed the Nature Lab’s living creatures, including the turtle that lives upstairs.

As well as learning about biosystems such as aquaponics, students visit the lab to make biomaterials—kombucha leather or mushroom foam, for example—that are composed of natural substances and are biodegradable.

Students taking part in the Hyundai partnership are looking at how scientifically informed design practices—from biomimicry and bioacoustics to innovative new ways of harnessing wind power—can enhance mobility technologically and ecologically.

In 2023, the Metcalf family established the Houghton P. Metcalf, Jr. (HD 91) Director of the Edna W. Lawrence Nature Lab and the Houghton P. Metcalf, Jr. (HD 91) Innovation Fund. The search for the new director was launched in August. The Innovation Fund will support grants to faculty and students engaged in research using the Nature Lab, equipment for the lab, and for student experiences. The endowment will provide the lab the tools to create hands-on learning opportunities and experiences for students and faculty while ensuring the lab has a permanent source of dedicated funding.

Fair Game

A student-run club nurtures game designers.

Nikki Strubinski 23 FAV doubts she would have landed her current job without Brown RISD Game Developers, a student-run club dedicated to all things video games.

Strubinski, who works on Fortnite at Epic Games, was a member of the club while at RISD. “Now that I’m doing production at a triple-A studio,” she says, “it’s easier than I thought because of the production experience I gained through the club.”

For the last decade, the club has welcomed any student interested in making video games, regardless of experience level. Members of the club work to develop a handful of games, pitched and voted on at the start of the semester, into completely realized prototypes. Typically the games that get developed are small in scale—“We’re not going to make World of Warcraft,” says Strubinski—but the range is wide, from dating simulators to action-based arcade games to rhythm games.

Narrative-based game pitches tend to get the thumbs-down, says Cindy Li 25 ID, who joined the club in her first year and now serves on the board. “Narrative introduces a lot more complexity,” she says.

“It makes the game less completable and more art heavy rather than programming heavy, and we’re trying to make something well-rounded in terms of experiences for both programmers and artists.”

During the game-development phase, students who are more familiar with the process teach the less experienced, asking questions to move the process along: What’s the core loop of the game? What makes the game replayable? What kind of assets do we need for art? How do we use the software?

Strubinski, a video game fan in high school who had never worked on a game project before RISD, pitched a game her first year called Rhythm Witch, which the club developed. “Having that authorship experience was really encouraging,” she says.

Students learn both specific skills and larger lessons. On the granular side, Strubinski picked up tips on making 3D assets. “If I’m making a rock, I can make it just like a rectangular prism or I can make a rock that has every single nook and cranny,” she explains. “That’s going to be way heavier in data than the simple asset, but you can actually mimic the look of the complicated asset—you just have to be

Words by Judy Hill Images courtesy of Cindy Liaware of the mapping of a 3D object—and still have it be easy to open on your computer.”

On a broader scale, students learn how to delegate tasks and respect differences in skill levels. “We had people who could only make one asset because they had to learn the whole software, and we had people who could have easily made the entire game themselves with their eyes closed,” says Strubinski.

To be a successful team player on a video game, Strubinski says you have to be “someone who can provide ideas and also not be hurt when your ideas get changed for something that fits the design of the game better or that suits the skills of the team better.”

Li says she learned how to talk to programmers “and engage with the progress and completion of things that I don’t fully understand.” Even now, she says, her knowledge of programming is limited, but she has learned to better communicate with programmers to “ask and see what they need.”

Brown students tend to be involved in the programming side and more RISD students in the artistic sphere. However, Li notes that the club includes composers and sound designers enrolled in Brown’s

music program, as well as students from that campus seeking a creative outlet for their artistic skills. Li says she often hears from programming students that the club is a way to see what they have learned applied in a context.

Recently, the club—which hovers around a hundred members—has attracted more graphic design and industrial design students. “With more designers on board,” Li says, “we’ve gotten better at designing the menus and the UI [user interface] of the games.”

Ultimately, the club’s goal, Li says, is to give first-year students a chance to “see if game design is their vibe,” and to provide a “stepping stone into the collaborative project experience” for those who know they want to pursue it as a career. Alumni and guest speakers regularly visit to talk about their experiences in the gaming industry, and to introduce students to the range of possible roles, from animation to modeling to coding to producing.

The most tangible takeaway for members of the club, says Li, may be the relatively complete video game they get to add to their portfolio at the end of the semester. And that, she says, is huge.

Future Designs

A studio course finds new uses for advanced materials.

What if you could design a key that changed color once you had locked the door? Or a crash test dummy that emitted light where it was injured? Or a hands-off shoe that automatically enveloped the foot? RISD students have designed all of these creations, and more, in an advanced studio course known as CATALYST that finds new uses for advanced materials.

Peter Yeadon, the RISD industrial design professor who runs CATALYST, has been interested in advanced materials—smart, nano, biotech— for at least two decades. Trained as an architect, with a practice in New York City, Yeadon was always drawn to “forward-looking visions for architecture and design, especially the many modernist manifestos that envisioned other possible futures that would be technologically driven.”

Yeadon has been teaching a version of CATALYST for two decades and has seen rapid advances in so-called “smart” materials that react to their environment and do cool things such as glowing, sensing, changing shape or converting one kind of energy into another.

“I’ve been encouraging the creative students at RISD to engage in the conversation around what this stuff might be used for in the future,” says Yeadon. “What other possible futures it might enable.”

Yeadon follows a materials-driven approach where he introduces students to several different kinds of materials and then asks them to use one to create a project that addresses an issue they are invested in. The resulting prototype could be as small as a tiny sensor or as vast as an entire architectural environment.

Nothing delights Yeadon more than a student applying the knowledge and skills they gained in the studio out in industry. For Kait Schoeck 13 ID, her CATALYST project involved working with a memory alloy, a material that changes shape to create an artificial muscle that acts as a power assist for astronaut gloves, which are famously stiff and unwieldy. Woven into the glove is an artificial muscle that contracts to help grab objects. Schoeck went to work for Microsoft, which was then designing its Surface Book laptop, whose screen detaches to become a tablet.

Words by Judy Hill Photos courtesy of Jeff Shen“Kait actually cut the wire out of her RISD prototype to show how this actuator could release the laptop screen,” says Yeadon.

Schoeck says taking Yeadon’s studio course “helped me learn that there is a whole world of materials that exist that can meet the needs of products without having to engineer them from the ground up. Learning about a material first and then finding a problem for it to solve ... opened my eyes to innovating around special material properties, and pushing boundaries of material creation.”

Jeff Shen 19 ID created a hands-off shoe that opens when the wearer steps on a mat and closes around the heel when they step off, thanks to a shape-memory alloy spring on the sole of the shoe. Shen, now a designer at Puma, says his studio work taught him to “respect and trust the process.”

“In my industry, we tend to jump into the design to create a presentable sketch as quickly as possible, because of the timeline pressure. I often think about what I learned in these classes to remind myself to take slower and longer exploratory processes at the beginning.”

Yeadon has taught iterations of CATALYST at Cornell and Ewha Womans University, in Seoul. What makes teaching different at an art school is that the students are also makers.

“We value making at RISD, so it’s enabled us to pursue tangible objects,” says Yeadon. That also presents certain challenges since unlike a university, where there might be a nanotech lab next door, RISD relies on partnerships with external organizations.

These partnerships have been mutually beneficial. The University of Rochester, for example, mixed up a batch of a polymer for RISD that changes shape dramatically and can move something a thousand times its own weight.

“That’s a great example of us working directly with researchers,” says Yeadon. “For them it had value because our students could demonstrate possible applications with this substance beyond the biomedical.”

Yeadon is already lining up potential materials for the 2024–2025 academic year, including a fiber that changes color in response to different contaminants in the environment.

A hands-off shoe designed by Jeff ShenMystical Laser Beams

Griffin Smith, who uses generative AI and custom language bots to create visual and interactive poetry, teaches classes at RISD in machine learning, digital culture and writing with AI.

Words by Judy HillJudy Hill: What did you think when you first encountered the language model GPT-2 [Generative Pre-trained Transformer 2]?

Griffin Smith: When I saw GPT-2—which is like ChatGPT’s grandparent—being trained to write poetry, I felt obligated to drop everything and think about what it would do to art. It became this consuming thought in my practice and in my life. In my workshops, we talk about [AI] tools, but at every chance, [we] broaden the context and ask, “What does it mean to reproduce a piece of art?”

You trained GPT-2 on your poetic voice, as well as on poets who have influenced you, to create hybrid poems.

I gave GPT-2 a big raw-text file of my work, and all the weights got adjusted until it sounded like me. Then I did the same thing with Walt Whitman and Dylan Thomas. I had ten tabs open, and I was fine-tuning them all at the same time. I would take my Elizabeth Bishop window and I would say, “Alright, you’ve learned her voice. Enough! Finish this Whitman line,” and it would write fifty, and I’d say, “OK, that one’s the best one.”

You insist that this exchange between you and the bot is not a duet because it is not human, but doesn't it feel like an agent?

GPT-2 doesn’t feel like an agent. It’s a pattern-continuing machine. With ChatGPT it feels like you’re duetting, because if you ask it to write a verse in the style of a Taylor Swift song it says, “Sure thing, whenever you’re ready,” and it’s pretending to be an agent. I didn’t have that experience with GPT-2. I just said, here’s a line and I’m going to use this fancy autocomplete, basically. But I knew once the technology was good enough, it was going to be what we’ve always known AI will be—a very ominous, faceless voice in a box that talks like a person.

What do you say to critics who say ChatGPT writes really bad poetry full of clichés?

If I write a poem that’s full of clichés, you’re right to judge me on that. The fact [that] ChatGPT does it doesn’t mean ChatGPT is bad. If you scrape the internet, 80 percent of what you find is average talk and clichés. GPT, which is a statistical modeling device, will assume most language is clichés, so that’s what it’ll write.

Do your students see Midjourney, an images-based AI program, as a threat or an opportunity?

My designers look at these tools and they say, “Maybe they’ll just speed up my workflow.” My artists will say things like, “This month, the color yellow has been very important to me [in my work].” So, they say, “I have a box that makes infinite images of any type. How will that help me ideate? What does it mean for me to make something by hand?” They have different concerns.

But every designer working with AI should think of it the way the artists do—it’s a big cultural gut that’s digesting every image ever made. You have to have fun with it. The designers can be more artsy and the artists can be more clinical, because these tools are at once like mystical and überefficient laser beams.

History Acquired

A body of work by photographer Jennifer Judkins now lives in the Smithsonian’s permanent collection.

Words by Abby Bielagus

Words by Abby Bielagus

When the Twin Towers fell on September 11, 2001, Chet Davis Judkins Jr., father of Jennifer Judkins 08 PH, happened to be in Connecticut, and not in Massachusetts, where he shared a home with his wife and children. He worked for a company that rented bulldozers, Caterpillars, staging lights—equipment one would need to clean up a major disaster.

Following his moral compass, Chet headed not north, but south to Ground Zero. For six days he stayed, ensuring that the equipment arrived and everyone was trained on how to use it. He also made roads with a grappling hook, delivered body bags to Battery Park in the hopes that there would be survivors and cleaned the machines’ air filters. When he needed to rest, he slept in his truck on the side of the road. Finally, Chet returned home to his life, his routine, his family.

One year later, after frequent back to back colds, bronchitis and trips to the ER he developed blood clots in his legs. Over time he got sicker and sicker and eventually was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2007, which some believe is caused by exposure

to jet fuel. It was the summer before Judkins’ senior year at RISD.

“I started photographing him,” she says. “My family lives about an hour from Providence, so I would drive home. I did that for almost a year.” Thirteen of those photos became Judkins’ thesis. But her documentation of her father continued well after she graduated, until his death in 2013.

A decade later, the Smithsonian acquired thirtyfour prints of Chet and the last days of his life. They also took a book that Judkins’ mom wrote a year after her husband died. It’s about their love story, the family they built and the life they led together.

“This body of work will be searchable in many different parts of the museum, like terrorism, health, medical and military,” Judkins says. The work will be used to educate the public about 9/11, the long term impact of that day and the many, many victims. Victims with wounds that slowly and silently festered for years. According to the World Trade Center Health Program there are about 30,000 people who can directly trace their cancers to 9/11.

Photo of Jennifer Judkins selecting prints

The Kids Are Alright

Brian Selznick talks about his latest book and how Steven Spielberg inspired the story.

Words by Abby Bielagus

Words by Abby Bielagus

Imagine one day you get a call asking if you’d write a movie for director Steven Spielberg. That feeling in the pit of your stomach, that pounding of your heart? That’s exactly how Brian Selznick 88 IL felt when he answered the phone.

The movie, as Spielberg originally envisioned it, would be about nature from nature’s point of view, with talking, singing and dancing plants. Did anyone want to watch a movie about dancing, singing plants? Selznick had his doubts. But what he enthusiastically said on the phone was, yes it was a brilliant idea, and he hopped straight on a plane to meet with the legendary director.

He dreamed that despite his nerves, he would hit if off with the man who made the greatest films of all time, and they would both agree that this particular movie shouldn’t be made.

And that’s mostly how it went. The two men sat at a conference table with producer Chris Meledandri in Spielberg’s office, below the sled from Citizen Kane, swapping ideas that tumbled into memories that turned into thoughts that became more ideas. When the meeting ended, Selznick found himself

back on a plane headed home with an assignment to work on the screenplay for a month.

“I panicked, because that wasn’t how the meeting was supposed to end ... I came up with ideas that Spielberg found exciting and pleasing that then sparked other ideas in him ... and suddenly I had to do this movie,” says Selznick.

Over the course of the next year, Selznick began to figure out how to tell this story. Spielberg originally wanted it to take place before the dinosaurs existed, when the world was mostly covered in ferns. Selznick moved the setting up a couple hundred million years so that people leaving the theater would have fallen in love with a world that looked more like our own.

“Spielberg loved that idea. I must say it’s very thrilling to present an idea to Steven Spielberg and have him love it,” says Selznick.

The movie was shaping up, but sadly so was COVID-19. The pandemic eventually derailed the plans for the film entirely, but Selznick, the reluctant writer, was now attached to the project. He proposed one last idea—that he continue writing the story, but as a book, not a screenplay.

Thankfully, Spielberg agreed.

The end result is Big Tree, which hit shelves in April of this year. The book tells the story of two seed siblings—Louise, who looks to her dreams for guidance, and Merwin, the parentlike rule-follower— who are suddenly thrust into the world to find a place to grow after a tragic split from their mama tree. Amidst a larger, obvious message about the need to save our environment is a more subtle exploration of the common, internal, adult struggle of whether we listen to our head or our heart.

“I wasn’t conscious [of that] when I was writing this. I was only conscious of writing these two characters who needed to be in conflict with each other. But I realized that it’s me telling the very loud, rational, frustrating part of myself to chill out a little bit and let the irrational, dreamy side take control more often,” says Selznick.

In many of his books, Selznick realizes long after they’re finished that he’d subconsciously been writing about himself.

“I often realize that most, if not all, of my characters are me in some fashion,” he says.

He gives the protagonists his interests, which range from Deaf culture to the history of museums, in the hope that the reader will care about the characters and, by proxy, care about their interests. His main characters are always children who are separated from their parents in some way. Although the orphan is a familiar children’s book trope that thrusts young people into an adult world where they are forced to make decisions and act independently, it’s also perhaps a means for Selznick to resolve the complicated relationship he had with his own father.

The eldest of three children, Selznick grew up in New Jersey. A gifted artist, he always felt supported and encouraged by his parents, but not always understood. Although he describes his childhood as “pretty happy” and void of “any real direct tragedy,” it was also quite isolating. At the age of ten, not coincidentally the age of many of his protagonists, he underwent major surgery on his chest.

“My sternum was born with a concavity that was causing severe pain when I had asthma attacks. I had this very intense relationship to illness as a child,” says Selznick.

Selznick was also a queer kid in a suburban town (although he didn’t know that’s what he was at the time) when there was little media representation of queerness or public support. His father, an accountant and a sports fan, shared little in common with his son.

“There was a sense of him being absent from a part of my life that probably parallels some of the things that I write about,” says Selznick.

His father died just before Selznick began writing The Invention of Hugo Cabret, the book that shot him to literary fame and also became an award-winning film directed by Martin Scorsese. Before his father’s death, they were on good terms and his father even met Selznick’s husband. In short, things turned out OK. Although this isn’t always how real life goes, it is true of the world Selznick creates for his characters.

“I want to be able to say to young people that life is going to be scary. Feeling scared is normal, and difficulties don’t come to an end, but there is safety at the end of the road,” says Selznick.

He doesn’t give his characters any special powers or magic to navigate the unique situations they find

themselves in. They’re normal people in extraordinary situations who unearth the necessary bravery to survive. And along the way, they create the families they need.

Selznick received a final phone call from Spielberg when Big Tree was published. This time Meledandri was on the line too. They wanted to congratulate him on the book and tell him how much they loved it.

In the end, the movie with talking, singing and dancing plants didn’t get made after all. But for Selznick, that’s OK. He realized that perhaps all along this was supposed to be a book, one that he could fully envision and draw, and not simply words on a page handed over to animators.

“With Big Tree, I’m very happy that there was this very unusual situation that led to the creation of the book,” says Selznick. “It’s strange that I ended up feeling very much that this is what it was really supposed to be.”

Selznick came to campus last June 2 for an event co-presented by the Fleet Library and the Alumni Association. Guests at Selznick’s visit in the Fleet Library.

Guests at Selznick’s visit in the Fleet Library.

2023 Guggenheim Fellow Christina Seely

Christina Seely MFA 03 PH is an artist who uses photography and recorded media as a vehicle to help the public stay with the uncomfortable truths of the climate crisis. As a child, she spent summers on the north shore of Lake Superior with her family, one of about fifty families who return every year to wander the forest, gather around beach bonfires to play music and help to conserve and protect the land. This experience became a touchstone for how Seely continues to relate to the natural world.

Abby Bielagus: When did you decide that you wanted to pursue photography full-time?

Christina Seely: I took photography in high school and loved it. Then in college, I went to Australia and New Zealand. It really changed me, especially meeting and learning from the aboriginal people. There are poetics and beauty in how they integrate with the land and the way they move through it. I went back to Australia again with a friend and took photos, and that was my senior thesis.

How did you arrive at RISD?

After college, I came back to the Bay Area for a year to figure out what I was going to do. I realized I wanted to be an artist. I went to the thenSchool of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston for a year and had access to an incredible community of photographers. I got into RISD with that work. I thrived at RISD—being in the community, talking about ideas and making.

What led you to Harvard Divinity School?

It’s a two-part answer. I moved to Alaska alone for six months in 2010 to experience perpetual day and perpetual night. It was deeply difficult, but it really changed my life. I started working with biologists and thinking about how you could describe climate change in an image. I researched coat-changing species, like the Arctic fox. The snow is starting to fall later and melt earlier, so the Arctic fox is bright white against a brown landscape. I went to Svalbard on a boat, north of Norway, and traveled. And this fox showed up, like this insane manifestation. And the day after I photographed it, the snow fell. That was the first of like eight fox stories—they just found me when I was working alone. One reason I think I went to divinity school was to grapple with these deeply spiritual experiences and to give myself vocabulary around that—how to talk about this without tripping on certain baggage. How do we bring the sacred into the conversation?

I think we’re afraid to say we have any sort of spirituality these days, because it’s either connected to the machine of institutionalized religion or it’s Wiccans and people dismiss you.

I did a huge project at the Harvard Museum of Natural History about species impacted by climate change, basically the sixth extinction. The effect it had on the public was so beautiful, really unexpected and profound. Folks thanked the director for providing a space to deal with the emotional side of it. We created a space, basically, of mourning. There has to be somewhere for us to link the data to the emotional or we aren’t going to get anywhere. We have two parts—we’re analytical and emotional—and art is the beautiful technology that can bridge the two. I went to divinity school to get permission to talk about this stuff, to bring the sacred into the room. And because I went to divinity school, people are listening.

You’ve decided to step down as associate professor of studio art at Dartmouth after a nearly twenty-year career in academia. Why?

The difficult decision to step away from full-time teaching to focus fully on my studio practice and personal life was led by knowing that right now the work I can offer as an artist is where I can be the most valuable. I will miss my students. It’s also the right decision.

2023 Guggenheim Fellow Claudia Bitrán

The American Chilean artist Claudia Bitrán MFA 13 PT splits her time between Chile and New York. A feeling of living two different lives, of being nostalgic for one place while living in another, has a great impact on Bitrán’s work. She builds bridges between seemingly separate worlds by combining fine arts and pop culture, painting with video. Represented by the Cristin Tierney Gallery in Tribeca, Bitrán taught at RISD and now teaches at Sarah Lawrence and the Pratt Institute.

From the Brittany Portraits , oil on canvas by Claudia Bitrán Studio

From the Brittany Portraits , oil on canvas by Claudia Bitrán Studio

Abby Bielagus: You were once a Brittany Spears impersonator, and she continues to factor in much of your work. What originally drew you to the pop star?

Claudia Bitrán: When I was a teenager, the first female body that I looked at was Brittany’s. The first film that I was impacted by was Titanic. The first fashion item I was drawn to was a white shoe. The first time that I got drunk, it was really dreadful. Everything I did in my teen years really marked me so much that I’ve never stopped thinking about it. That’s when you first start feeling really profound emotions and existential, complex ones.

Does Brittany know that you create art about her?

Yes, she does. We met in 2017 because she had a dance competition on Facebook and I won. I was flown to Vegas to meet her in person. Right after that, they brought me to the front row and she sang “Womanizer” looking at my face.

You’re a painter, an actress, a dancer, an animator, a multidisciplinary artist. Why did you decide to focus on painting at RISD?

All of the art that I do starts with drawing or painting. I make videos in a very painting-based way. I start from a general wash in the video and then I go into more details. I think about the layers in video like I think about paintings. I like the relationship between the still frame and the moving image. I think painting is like the mother of all frames.

What brought you to RISD specifically?

When I visited RISD, an alum named Katie Bell MFA 11 PT was in the painting department and she gave me the tour. Katie is an incredible artist, and during the tour I thought, “I want to be wherever she is.” I got a very good vibe from all the students there, all of these incredible painters I was meeting for the first time, but I felt like I knew them forever. Katie and I now work together at Sarah Lawrence. We’re very good friends; we became friends the day she gave me the tour of RISD.

Do you have any memories of RISD that really stick with you?

My experience at RISD was nothing but positive, transformative. I was coming from a very conservative painting education, and RISD was so open and helped me experiment with everything I was interested in. Faculty member Angela Dufresne, a painter and in the grad program, became not only a mentor but a friend, a mother, everything. She is a very important figure to me; we hang out all the time. She is a spectacular mind. She’s a walking opera. Kevin Zucker 00 PT, another one of my professors, made my mind switch. Meeting Angela and Kevin was the jewel, the heart of my experience.

Can you talk a little about the Guggenheim Fellowship?

I applied to the Guggenheim Fellowship because I’m working on an enormous project that I won’t be able to finish if I don’t get money. It’s a multidisciplinary project—a shot-for-shot remake of the film Titanic. I’ve been doing that for nine years, and the project has involved more than eight hundred participants from over twenty cities across the United States, Chile and Mexico. I’ve now filmed all of the scenes and I have to go into post production.

Let’s Eat

Daniel Pelosi, or @grossypelosi, talks about the secret sauce that has launched his new career in the food space.

Wordsby Abby Bielagus

IF YOU FOLLOW Dan “Grossy” Pelosi 05 IA on Instagram, you might think you know all there is to know about him. After all, he’s been documenting his entire life online for years. On the surface, his story is a familiar one—a pandemic-induced hobby (cooking) becomes a soulful full-time gig. But when you look at his analog life, the narrative isn’t as prescriptive as you would think. Turns out, there’s an untold tale here.

First, let’s talk about the name. No relation to the former speaker of the House, Nancy, “Grossy” was inspired by the 1990s movie Never Been Kissed. In it, Drew Barrymore plays an undercover reporter who while infiltrating her old high school reverts to her adolescent persona, unfortunately nicknamed Josie “Grossie” Geller. Pelosi’s friends couldn’t help themselves from making the obvious rhyme. But unlike the movie script, in real life the nickname was made in loving jest and Pelosi fully embraced it, making it his handle for every one of his digital personas.

“What I like about it is that it’s not serious, it has a sense of humor to it. People are so nervous about getting a recipe right, but you’ve got to mess up, that’s how you learn. My name is inherently stupid. I’m not going to come in and tell you how to sous vide. Let’s make some ‘manigot’ and we’re good to go,” he says.

And this is where we start to see what sets Pelosi apart from others who became internet famous somewhat overnight. He embraces the messy. His persona is not carefully constructed to convey an unachievable state of perfection. It’s actually the opposite. He encourages everyone to dive into

a recipe and perhaps make mistakes to discover the joy in the process, even if the end result isn’t pretty or all that photogenic. Some of his most popular recipes come from his grandfather “Bimpy,” who makes pasta e piselli with just four ingredients, none of which are salt and pepper.

To Pelosi, food is family. Quite literally. In addition to Bimpy, he takes inspiration from his mom, his dad, his Uncle Phil, his Grandma Millie, his Aunt Chris and his sister, sometimes directly crediting a recipe to them. Many of his recipes are adaptations of what these beloved relatives fed him growing up.

To really know Pelosi is to return to his AmericanItalian-Portuguese childhood home in Waterbury, Connecticut. Most days he helped his mom cook at the counter, and on Sunday mornings, his dad and grandpa cut coupons at the dining room table, a loaf of bread between them. Sharing any meal could be a mix of aunts and uncles and cousins, and inevitably the family would discuss what to eat at the next meal. Pelosi was a self-described indoors kid and spent afternoons running errands with his mom to SherwinWilliams, where he would select a color to repaint his bedroom for the fifteenth time or wallpaper to redecorate the dining room for the fourth time. He made clothes for his Barbies at his grandma’s house and cakes with his grandpa. Home wasn’t a building but rooms where loving relatives embraced Pelosi for everything that he was and showed their love through food. When Pelosi came out, his family was totally accepting. His mom asked if he would have two men on his wedding cake.

So it’s no surprise that when he went to RISD, he was homesick. In fact, he often returned to Connecticut on the weekends, much to the bewilderment of his peers, college students who perhaps used their undergraduate education as a way to escape their families. Despite his longing for home, Pelosi thrived at RISD.

“I was obsessed with it. I loved being in my studio and being in my classes,” he says. Initially, he wanted to become a graphic designer, but one of his printmaking professors, Ken Wood, forecast a different future for him.

“[Ken] used to design stores for Williams-Sonoma and said he saw that as a career for me. It was like he read my soul, the amount of time I spent in Williams-Sonoma with my mom, eating bread and olive oil at the cash register ... it was incredible. I had always loved interior design but I wasn’t interested in building from the ground up. I was interested in reusing spaces that already exist. So I pivoted to interior architecture, and that really became my thing,” Pelosi says.

Pelosi embraced all that RISD had to offer and gave it everything he had. He spent a winter session in Amsterdam and did the European Honors program in Rome. Living abroad meant diving deeper into his education while also learning how to be away from his family and form a home of his own.

Here the story might become familiar to Grossy followers, because Rome was where the now-beloved foodie personality began to take shape. Every day on the way home from his internship, Pelosi would stop

at the famous Campo dei Fiori farmers market and stock up. He would return to the kitchen he shared with ten other students, loaded down with ingredients, and everyone would gather for a meal. Pelosi summoned the collective energies of his grandma, his aunties and his mom and commandeered that kitchen, giving everyone a task. He owned the kitchen. And suddenly a switch was flipped.

Pelosi learned that he didn’t have to return to Connecticut. He could bring “home” to wherever he was—through food. When he graduated from RISD and got a job at Gap’s store-design department in San Francisco, he would make a big batch of marinara when he missed his family. He says it’s the best scented candle, because it makes your home smell like marinara sauce for a whole week. He also made meatballs and lasagna and other foods from his childhood, but this time with his own deliberate spin.

He also vigorously pursued his career. He was at Gap for six years, doing everything he “could possibly do, running around and welcoming myself into meetings that I wasn’t invited to. I used the creative problem-solving that I learned at RISD to change people’s minds and be hyper-creative,” he says.

From there he accepted a job as a creative director for Wieden+Kennedy, in Portland, Oregon, creating experiential retail spaces for brands like Coca-Cola, Converse and Nike. Then he finally returned east to New York City, where he worked for Ann Taylor and helped launch their brand Lou & Grey. By now it’s 2020.

Previous Pelosi photo by Andrew Bui, which is also the back cover of his newly released cookbook, Let’s Eat Right Pelosi’s olive oil ice cream from his cookbook

Here is another well-known chapter to Grossy fans. During the start of the pandemic, he was housebound like we all were, furloughed from his job. He continued to document his life on Instagram to his 3,000 followers, but instead of photos showing the dinner parties he hosted, he began to post about every single meal he made, every single day.

“I was posting nonstop. It didn’t matter if only five people saw it. I had to post. I’ve always done it. It was like I was in ten years of boot camp sharing myself on Instagram until it finally made sense,” he says.

Finding one’s self inside the comfort of one’s home made sense not just to the followers, whose numbers began to increase, but to Pelosi himself.

“I’ve always created a really great home for myself that I feel comfortable in. Turns out a lot of people don’t know how to cook and don’t know how to make a home for themselves that they enjoy. So I was able to become a resource for people. They were responding to the way that I live my life and my sense of humor. People would message me and tell me that I was keeping them alive. But they were also keeping me alive,” he says.

Pelosi attributes a lot of his success as Grossy not to his cooking but to his art and design background. His followers are drawn to his personality and his homestyle recipes, which are certain to elicit audible sighs of pleasure with each bite. But more intuitively, what is compelling about Grossy is the aesthetic—it’s bright, it’s joyful, it’s humorous. It is a well-designed and well-executed brand with a distinctive personality.

His brand doesn’t look like all of the filtered and choreographed content on social media. It’s polished, for sure, but in a way that appears genuine and natural. It’s that special magical sauce that makes people respond to Nike, to Target, to beloved brands that know how to speak to us.

For years Pelosi created identities for brands, and then one day he was the brand. But behind this well-crafted brand is a guy with a family, a boyfriend and a fully stocked pantry—into which he welcomes us all.

When you peek behind the Grossy curtain, you still get Dan, a real, funny, loving, warm and boisterous guy at whose table you would love to pull up a seat.

“The fact that I went to design school and understand creative problem-solving and had a career in retail and marketing—all of those things make up for whatever I lack in the kitchen. I was able to brand myself, and I think that is a differentiator. I created a space for people that had a point of view. I was using all the same tools that I did at RISD and throughout my career, but I am the brand. It’s allowed me to be so authentic,” he says.

In 2021, Pelosi was able to quit his job and focus on Grossy full-time. His first cookbook, Let’s Eat: 101 Recipes to Fill Your Heart & Home, hit shelves in early September, and as of our interview, he had twentythree stops planned on his book tour, many of which were already sold out. He now has a book agent, a manager and an assistant and is repped by WME, an agency behind almost any A-lister you can name. He’s been on The Rachael Ray Show, Good Morning

“If I can build a community of joy and happiness and goodwill, that’s incredible. If I can do it through food— that’s a dream.”

Daniel Pelosi

America and The Drew Barrymore Show. He currently has 146,000 followers.

“If I can build a community of joy and happiness and goodwill, that’s incredible. If I can do it through food—that’s a dream,” he says.

If you look beyond the kitchen, Pelosi’s love of art and design is obvious. His former Brooklyn apartment was so well decorated that it was featured in media outlets like Domino and Curbed. There was art everywhere, most notably covering an entire wall across from his large dining table. Each piece of art in his home has a story. When people ask him where he gets it all, he has no single answer, because it comes from everywhere—from markets, vintage shops, his friends’ children.

“I think the value comes in being able to say ‘This piece of art is from my college friend, it’s one of a kind.’ That very much relates to the recipes I make, like ‘This is Bimpy’s pasta.’ The storytelling is why these things are so special to me,” he says.

Luckily for him, his college friends happen to be artists, some of whom have risen to acclaim. For instance, the large abstract painting of an interior—that’s by Shara Hughes 04 PT. Or the art that always gets the most DMs: an unfinished painting of two men wrestling, by his college friend Rory Lustberg 04 PT, who was planning to throw it away. There’s Lauren Geremia’s 04 PT painting of a grocery store, Brianna Ashby’s 04 IL illustration of Nathan Lane’s drag character in The Birdcage. Although Pelosi is mostly known for his recipes, he calls himself a food and lifestyle creator and hopes

to—not shift, exactly—but return to interiors in the future. “I think about design all day long. I’m designing a lifestyle,” he says. And this is the final thing that sets Pelosi apart: he didn’t hate his day job. He loved being a creative director with a team who, under his guidance, made some really cool spaces. He didn’t leave a soul-sucking career to find his true self. It’s more like the world stopped and found him.

He just recently moved out of the well-decorated Brooklyn apartment into a smaller space and bought a house in upstate New York. It’s by no means a fixer-upper, but Pelosi will certainly move his personality in through wallpaper, paint and lighting. He wants to redo the kitchen and have a big garden. And of course he’ll share everything online.

These days, though, he is a bit more thoughtful about what he shares. Writing his cookbook was challenging because it took two years, and in that time he wasn’t able to share everything he was doing. He had to keep all 101 recipes secret. He also wants to connect “Grossy” with “Dan.”

“I’m always going to figure out ways to share information. I’m still working through the best method to do it. Managing how much information people want from me has been a really interesting creative solution,” he says.

Brodie Neill safeguards the planet, one piece of furniture at a time.

Abby Bielagus

Form and Function

FEW OF US SEE TRASH on a beach and think of creating something beautiful. But we aren’t Brodie Neill MFA 04 FD, the Australian furniture maker whose Gyro table, made from repurposed plastic trash, skyrocketed him to international fame when it was unveiled at the London Design Biennale. No one-hit wonder, Neill’s chart-toppers also include the Remix bench, made for the Apartment Gallery in London; the E-Turn bench and the @ Chair, both of which were recognized in Time magazine’s Design 100; and his Alpha chair, which has a permanent home in the RISD Museum. Like a fashion designer who creates for the runway as well as the closet, Neill is also the creative director and founder of the contemporary furniture brand Made in Ratio.

To refer to him as a furniture maker doesn’t feel quite right. Artist, environmentalist, creative director, businessman, activist—all of these titles also fit— but squishing Neill into any singular profession feels reductive.

“After all these years, it’s still very difficult to put a finger on what it is I do. People always ask me, ‘Is it functional art, is it decorative art, is it design?’ It’s probably more than furniture design, but that’s what I call myself because that’s the safe place that I keep coming back to,” he says.

So we’ll call him a furniture maker. When you meet him, the description fits. Although our meeting was virtual, he in his London studio and me in my Boston apartment, my first impression was how earnest and humble he seemed. He was soft-spoken, even-

keeled, with hair slightly askew, wearing a blue work shirt. His backdrop was a bright, highceilinged, minimally decorated studio. He looked like he could’ve just been tinkering in a workshop. And he had been, sort of. Before our call, he was in the middle of digitally designing a commissioned piece for a client using the latest three-dimensional technology, with his sketch pad at his side.

Neill creates in a world of opposites. He’s equal parts craftsman and digital denizen, drawn both to past tradition and future technology.

“It’s knowing when to step into one and when to step into the other,” Neill says. “Even though I’m working in this virtual world when I’m sculpting in infinite space, I’ve still got one foot on the ground. I have to imagine how the shadows will play, how the hands will run over it, how the light will bounce off it,” he continues.

He’s never making for the sake of it but constructing in reality, often limited by his own self-imposed restrictions. A table can’t just be a pretty thing; it’s also an object a person must get their legs under, chairs have to fit around it. Everything he builds has to have a function, a purpose.

Neill has been attracted to building furniture, to working with a medium that demands constraint, since he was a kid. Growing up in Tasmania, creativity was nurtured among him and his five siblings. They were often taken to museums and galleries and encouraged to pursue their own artwork. Neill took not to the easel but to the woodshop, making chairs and tables when he was twelve years old.

Left

Commissioned by design research gallery Matter of Stuff, the Latitude bench spans 2.2 meters and is made of 422 salvaged wooden dowels.

Photo by Angela Moore

Above

The @ chair in mirror-polished stainless steel encompasses the entire configuration of a chair within a single gesture. It was included in Time magazine’s Design 100.

Left

Commissioned by design research gallery Matter of Stuff, the Latitude bench spans 2.2 meters and is made of 422 salvaged wooden dowels.

Photo by Angela Moore

Above

The @ chair in mirror-polished stainless steel encompasses the entire configuration of a chair within a single gesture. It was included in Time magazine’s Design 100.

What compelled him then and continues to fascinate him today wasn’t just artistry but science.

“As a creative child, I wasn’t interested in just sculpture or painting. It was the physics, the science of it, which I found fascinating and still do,” he says.

His mom still has his early pieces, and she isn’t shy about showing them off. Although Neill finds it embarrassing, he also admits with a smile that it’s a testament to his work. Decades later, you could still have a seat in one of those chairs.

He perfected his furniture-making skills at the University of Tasmania and arrived at RISD confident in what his hands could make but curious about what his mind could dream up. He experimented with digital three-dimensional tools and began to release that anchor he had in the real world.

“Some of the early projects I did in the two years I was at RISD inspired a whole series of work,” he says.

After graduation, he moved to New York City and took a job at L’Oréal, designing packaging and displays. Although he found it somewhat interesting, he strongly knew it was not what he wanted to do forever. Along with a fellow RISD grad, Neill took a collection of his work to the young designer’s platform at Milan Design Week. He was quickly recruited to design products for European clients, and he soon decamped for London. There, all of those RISD-born concepts took literal shape. Salvaged wood from a nearby Jaguar car factory became the Infinity bench. That piece went on to Milan Design Week, and Brodie Neill’s career was launched.

Over the past two decades or so, Neill’s star has only continued to rise. What sets him apart from his contemporaries is his progressive use of form and his dedication to reclaimed materials. It would be easier, of course, to simply buy what he needs, but Neill seeks to rescue what has been tossed aside.

“There is no way that my moral composition would be responsible for cutting down virgin trees and dragging them out of the Amazon or somewhere when there is so much material at your fingertips,” he says.

His loyalty to the natural world is rooted to his childhood in Tasmania.

“It’s a very wild and natural place. It’s sparsely populated and has some of the cleanest water and air in the world. The natural materials there are gorgeous, and when they reach your hands, they’ve taken tens if not thousands of years to grow. We have a responsibility to distill some kind of honor into that object and use it in a very respectful way,” he says.

Rhodesian mahogany sourced from a renovated hospital became the Latitude bench and the Altitude chair; reclaimed African hardware, once laid as a herringbone parquet floor at a school, is now the Meridian bench; and a single surface of infinitely recycled bronze makes up the Atmos console and desk.

Perhaps his most stunning example of literally turning trash into his treasure is the aforementioned Gyro table, and the story of its origin takes us back to Tasmania.

Left

Neill was strolling a remote beach that he used to visit often as a child. He remembered it being picturesque, and now debris scattered around his feet—plastic bottles, lids, a detergent bottle, the handle of a toothbrush—all in various states of decay.

“I was thinking, here is a plastic object that has been made from fossil fuels dug out of the ground, refined and shipped across the world. It’s used for a moment, but the chemical compound in it is designed to be indestructible. I thought something had to be done,” he says.

Coincidentally, Neill had been asked to put forth a submission for Australia for the first-ever international design forum to take place at the London Design Biennale in nine months. He wondered, Could all of those bits of plastic be the foundation? He collaborated with the National Gallery in Australia, the University of Tasmania, marine biologists, oceanographers and beachcombers, who collected tons of plastic trash from their shores.

After some trial and error, Neill turned to a traditional terrazzo technique to bond over half a million plastic fragments together. He then cut and inlaid the “ocean terrazzo” into a kaleidoscopic pattern to adorn the table’s top, creating a modern specimen table. He named it Gyro, from the word “gyre,” meaning a giant circular oceanic surface current.

“When it was unveiled, it was a glowing orb of an object that drew people in. Once they realized that this Milky Way-galactic mosaic was made of half a million fragments of plastic that used to float in the

ocean, it really made them understand the magnitude of it,” he says.

Neill himself was as “gobsmacked as anyone” when the top surface was cut back and the tabletop was revealed. What came as an even greater surprise was the international spotlight that shone brightly on Neill. He became an unofficial steward of the oceans. He was invited to talk on nightly news shows, in newspapers, in magazines, on the BBC World Service and at the United Nations. Seven years later Neill has gotten only a bit more comfortable in his role as environmentalist, activist and educator.

“They say art is like putting a mirror up to society. I’m putting people face to face with the problem and turning the problem into a very beautiful solution. They’re objects of hope that tackle some very important environmental issues but are by no means a golden ticket.”

What he knows how to do is rediscover, tinker and return time and time again to the materials. He’s still working with the discarded plastics but he’s found a way to make them into more functional Lego-like bricks. Microplastic fragments left over from the Gyro table went to build the Jetsam table, recently acquired by the Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum as a launchpad to discuss Neill’s work around ocean plastic. He’s still designing with wood, metal and glass for the ever-successful Made in Ratio—reexamining familiar ingredients from a modernist lens.

“People say everything’s been designed before, painted before, written before—come on, there’s still so much to be done,” he says.

“They’re objects of hope that tackle some very important environmental issues but are by no means a golden ticket.”

Brodie Neill

State of Flux

Corsino

Words by Judy Hill

Corsino

Words by Judy Hill

MARIMONDA IS PART MONKEY, part elephant, the sly trickster of folklore that crowds come out to see at Colombia’s largest carnival, a music and dance festival that takes over the Caribbean coastal city of Barranquilla for four days every year leading up to Lent.

Marimonda also flits in and out of the most recent series of paintings by Ilana Savdie 08 IL, on view in Radical Contractions through November 5 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. We see the mischievous spirit in tantalizing glimpses, a mask here, a hand there, promising to resolve into a figure, but just as quickly dissolving or shifting into another shape altogether. Like much about Savdie’s work, Marimonda refuses to stay put.

By turns seductive and nightmarish, Savdie’s paintings dazzle the eye with luminous, tropical shades of lime and magenta, flesh pink and cobalt. Expanses of thick brushwork butt up against fluid swaths of gauzy pigment. Sections of hard-edged detail meticulously painted in oil border fields of wrinkly, raw beeswax. Abstract forms rooted in the physical body—tissue, tendons, bones and organs— combine, intertwine and melt into one another, never quite coalescing into a legible narrative. Parasitic forms coil and twist, bulge and constrict. We feel a twinge of revulsion but we can’t stop looking.

“I get a lot of pleasure in the fusing together of disparate parts and colliding of things that aren’t meant to exist together and arriving at abstraction through monstrosity,” says Savdie, who was raised in Barranquilla and Miami and now lives in Brooklyn.

The “monstrous,” she says, forces you to face what you might rather avoid.

“I look to the history of horror often, and the monstrous is the thing that throughout the film becomes bigger or more apparent. The longer it gets ignored, the bigger it gets and eventually it has to be contended with.”

For Savdie, the thing that must be contended with is the daily stress of living in a world where civil rights are under attack—from the political oppression of minority groups to the theft of bodily autonomy— and the threat these losses imply. It’s not that we are dealing with new systems of oppressive power, she says.

“What we’re experiencing is history repeating itself, which is what’s most terrifying—the things that we thought we were moving away from, we have found ourselves moving towards.”

Parasites of various kinds show up frequently in Savdie’s paintings, partly because she finds them fascinating aesthetically, but also because she is intrigued by their survival strategies and how those can serve as parallels to the ways she contends with the systems of oppressive power.

“Parasites serve as agents of change,” she says. “They invade a host body and force it to change, and that’s a really interesting concept to me.”

Savdie’s paintings disorient us because everything is in a state of flux and we never quite know what we are looking at.

“I’m very interested in how one form can almost be finishing the sentence of another form,” says Savdie.

Ilana Savdie’s paintings— currently on exhibit at the Whitney—dazzle, beguile and refuse to stay put.

Pinching the Frenulum, 2023

Pinching the Frenulum, 2023

“So, there’s never finality to anything. To have the desire for something categorizable and never quite have that longing fulfilled feels truer to what I consider a natural state of existing.”

FOLKLORIC TRICKSTERS like Marimonda find their way into Savdie’s work because they also are symbolic of a world—the carnival—where social norms are inverted, identities are fluid and the grotesque exaggeration of the body as a mode of mockery becomes a theatrical means of resistance.

Savdie traces her vibrant color palette directly to the experience of growing up in the Caribbean, but she recognizes that it is also strategic.

“It’s this desire to create a perverse palette that is both saccharine and sweet and seductive and at the same time acidic and toxic and chemical,” she says. “There’s a duality of palette and content that feels like a bait and switch. I’m seducing you with this palette and forcing you to look at a parasite.”

Growing up, Savdie says she was drawing and painting before she could talk and was fortunate to be in a household where art was celebrated. “I was always entering into the world through the visual first,” she says, and Carnival was an integral part of that visual universe. Last February, Savdie returned to Barranquilla to attend the celebration for the first time as an adult.

“I came back to it with a theoretical education of the carnival, having done readings about the carnivalesque, and with a different lens,” says Savdie, who also took part in a parade with a queer-centric group

called Disfrázate Como Quieras, or Dress as you Wish. The experience of walking in the parade with this group was so inspiring that the day she returned to her Brooklyn studio she immediately began work on what became Radical Contractions, her series at the Whitney.

She had intended to make just three new pieces for the show, rounding out the exhibit with loan pieces. When she started working on the new paintings, though—each a whopping 120" × 86"—she realized they needed to be a cohesive series uninterrupted by any shift in scale.

“I wanted this sense of being surrounded almost in a cathedral-like fashion,” she says. “There are so many references in my work to the baroque and to religious paintings and the history of excess, and I wanted to bring that into this small space.”

THE BROOKLYN STUDIO where Savdie works is large, white and serene, except that, in typical Savdie fashion, it’s also chaotic and crowded and filled with color. Photographs and other reference images are pinned up on every wall, and masks and skeletons and books abound. “It’s the excess of sources that’s important to this work,” she says.

New York City was where Savdie had dreamed of living as a teenager growing up in Colombia and Florida. When it came time to think about college, she applied to several in Manhattan and also to RISD, since a girl from her high school had attended.

“I thought I was absolutely going to New York,” says Savdie of her mindset as she began her college

Left Las Tinieblas, 2023 Photo by Lance Brewer“It’s this desire to create a perverse palette that is both saccharine and sweet and seductive and at the same time acidic and toxic and chemical.”

Ilana Savdie

visits in the city. “I would go to the building that was dedicated to the art school and I would go to each floor dedicated to a different department,” she recalls, “and then I went to Providence and saw RISD, and I was like, ‘Oh, the entire school, every building is the art school!’ The second I got to Providence and saw RISD, I accepted.”

Savdie majored in illustration at RISD because she thought it seemed more practical career-wise than painting, though the painting bug never went away and she was still “making six-foot paintings in my tiny illustration cubicle.”

After RISD, she took a one-year photography program and found work as a retoucher in the beauty industry. Savdie says she wasn’t a very good illustrator or a very good photographer, but both have informed her current work in the way she uses the illustrative line and the means by which she destroys, perverts and contaminates images using the same tools she once used to create utopian stock images.

Eventually, after stints as a creative director and a graphic designer, Savdie found her way back to painting and made the decision to go to graduate school, earning her MFA from Yale a decade after her RISD undergraduate degree.

Savdie’s current art practice always starts with a sketch, sometimes figurative and sometimes more form-centric, where she “starts to pull out or unravel bodies or figures and work out how things come together, think through joints or where something meets, penetrates, dissolves.” Decisions about color

and the placement of the wax areas follow, and then she begins to block out the painting.

The sketch serves as the basis for a separate work on paper but Savdie’s approach to that is not linear either. “I go back to it later, sometimes after the painting is done, sometimes a year later, and it becomes its own separate piece,” she explains. “Sometimes the painting becomes a sketch for the work on paper. There’s this kind of feedback with it.”

With the painting blocked out, the process becomes about thinking through different ways of applying paint, and the “tumultuous coexistence of different art historical references,” says Savdie. She uses wax because she finds the material visually interesting and organic, and viscerally referential to the body.

Savdie calls her artistic practice “raw” and “responsive,” and says that when she’s in her studio she is in a “very vulnerable state” that she tries to hold on to. Though she is working from a sketch, there is an instinctive element and a spontaneity as she spills and pours paint and encaustic onto the canvas laid out on her studio floor.

“The fundamental part of this practice is about the relationship between the things that I’m trying to control in a material that’s trying to control me,” she says. “This kind of power play between myself and the material is the most frustrating part of the work and the most exciting. It’s the material rejecting me and then me rejecting the decision the material made. It’s a constant back-and-forth, almost like a game of ping-pong.”

“This kind of power play between myself and the material is the most frustrating part of the work and the most exciting.”

Ilana Savdie

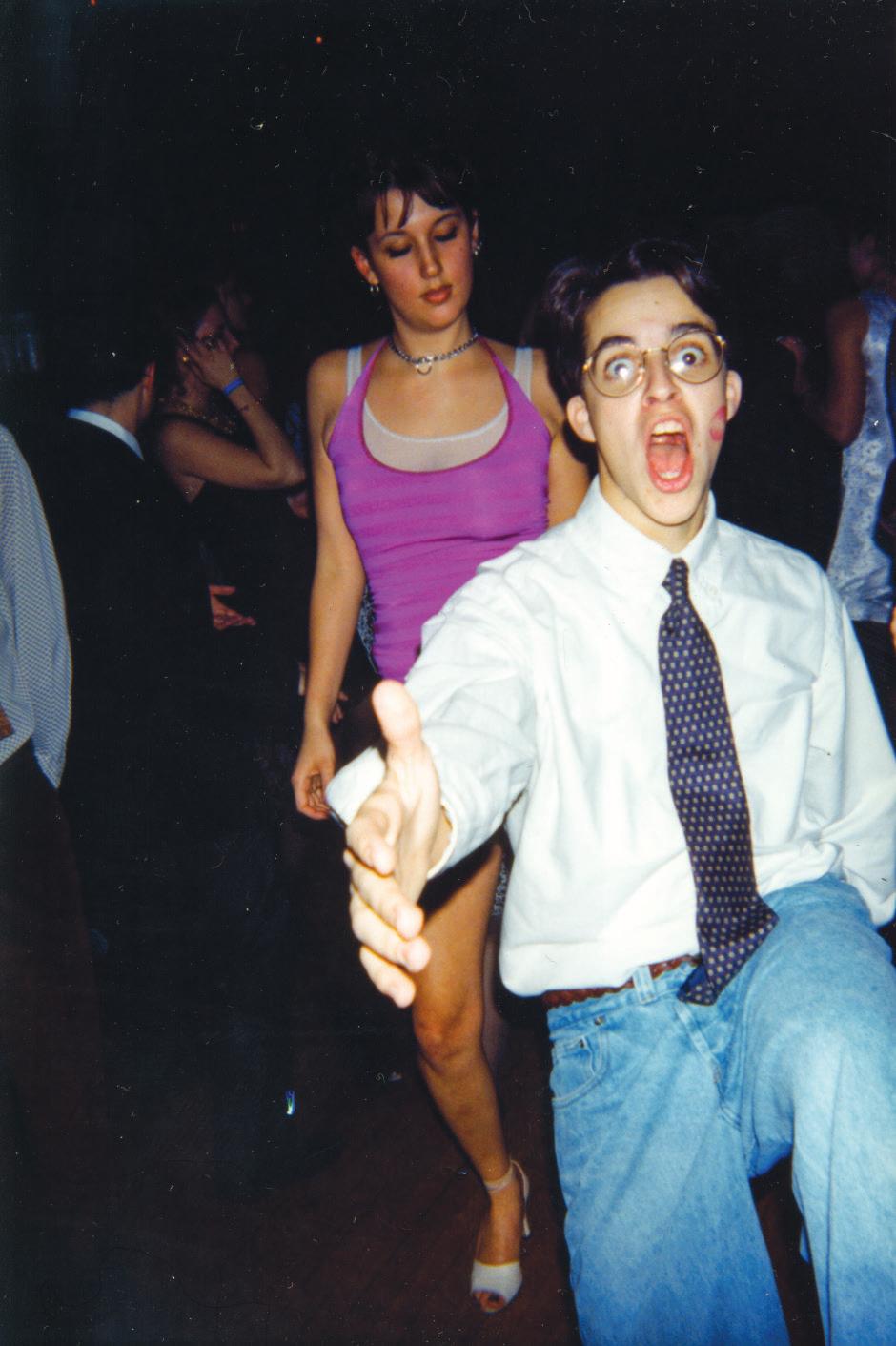

90s Art School

The founder of cult Instagram account 90s Art School shares his motivation for starting the project, what keeps it going and why these moments should be remembered.

Words by Matthew Atkatz

THE 1990S WAS the last decade before digital technology fundamentally changed image-making, and, in the process, reinvented culture. As the millennium drew to a close, film photography was ubiquitous, yet in the following decade it would be replaced by digital image-making. But the real shift in photography wasn’t just the advancement of digital cameras, it was the internet, and more specifically social media, which rewrote the rules on the way we take pictures, and the way we pose for them.