10 minute read

Waiting to Exhale

New government study explores impact of wildfire smoke on indoor air quality

By Greg Nilsson

Advertisement

Evidence-based information on indoor air quality (IAQ ) at Canadian healthcare facilities is lacking and yet it is crucial in helping facility managers make adequate decisions during times when IAQ may be compromised, specifically during wildfire season.

To help solve this problem, the National Research Council of Canada’s (NRC) Construction Research Centre launched a project in 2018, to identify the impact wildfire smoke has on healthcare facilities’ IAQ. The NRC’s study began by characterizing outdoor and indoor particle concentrations to establish baselines for technological responses. An advisory committee was formed to enable stakeholder consultations. Committee members included Health Canada, the Canadian Forest Service, representation from provincial health ministries, emergency management offices and facility maintenance operations from Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia. The committee identified a lack of evidence-based direction in how to react to IAQ challenges during wildfire smoke occurrences, given response practices are not systematically reported to allow for the development of generic guidance. With this in mind and to better understand the response practices being used by

different facilities, an online survey was distributed to healthcare facility management and operations (FMO) staff in Canada’s four westernmost provinces. All respondents indicated that in 45 per cent of cases, wildfire smoke had a prolonged negative impact on IAQ. The average length of a wildfire smoke event during the 2018 season was 30 days; the longest event lasted 60 consecutive days.

MITIGATION TECHNOLOGIES The most common mitigation approach to deal with compromised IAQ was to install filters with higher Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) ratings for the outdoor air intakes (91 per cent of respondents). Portable air cleaners were also used by 45 per cent of respondents. Participants stated that for infection control purposes, portable air cleaners were not permitted in sensitive areas as they may disturb air flows intended to minimize infection transmission risks. In 57 per cent of cases, the actions taken did not reduce the number of IAQ complaints received by FMO staff. Sites that used multiple approaches had the best outcome in terms of reported improved IAQ and

reduced complaints. However, according to the survey, no particle monitoring was performed during wildfire smoke events.

As literature did not reveal any data regarding the indoor particle concentrations in Canadian healthcare facilities, field monitoring at three B.C. locations heavily impacted by wildfire smoke in 2018 was undertaken to better understand the relationship between outdoor and indoor particle concentrations. The parameter PM2.5 was chosen since it may indicate the presence of potentially harmful airborne particles. PM2.5 is tiny inhalable particulate matter, with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 micrometres and smaller. There are no recommended safe exposure limits for PM2.5 in Canada. The knowledge obtained from monitoring is critical for a later, targeted approach, when evaluating technologies and solutions to reduce inhalable particles. These measurements will also be helpful in creating baseline data.

FIELD MONITORING The monitoring study was set up in two phases: Phase 1 was a preliminary study conducted during winter and Phase 2 a follow-up study during fire season.

The air handling units, ducting and control strategies for the monitored healthcare facilities were found to vary considerably at each location. Due to this complexity, a simple model was developed and applied. In this model, the facility was split into two basic IAQ zones: a core zone where indoor air is mainly provided through the HVAC system, and a periphery zone where there is higher potential for infiltration due to occupant movement through entrances and exits. In this case, the periphery zone monitoring location was the emergency room.

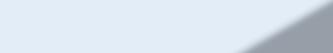

Phase 1 took place at Victoria General Hospital on Vancouver Island, between December 2018 and January 2019. Data collected showed an association between indoor and outdoor particle concentrations for the periphery zone, but no correlation for interior zones. For this phase of the study, five particle counters were deployed in the indoor areas and one for the outdoors. The different particle counters deployed in each zone reported very similar data. So, during Phase 2, only two counters were deployed, one monitoring unit for each area.

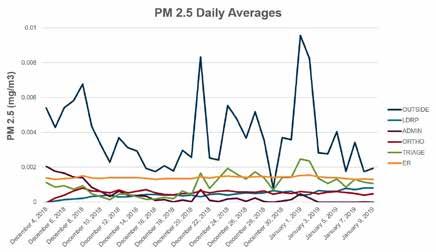

Phase 2 monitoring was completed between July and September 2019, at

Daily averages of PM2.5 monitored during Phase 2, as listed by monitoring locations. t

three B.C. sites: Victoria General, Royal Inland Hospital in Kamloops, and Kelowna General Hospital. Data collected revealed a strong correlation between indoor and outdoor particle concentrations for the periphery zone, as was seen in the first phase of the study. The monitoring was not exhaustive as it was only completed at three sites, so a level of caution should be applied when drawing conclusions about the filtration effectiveness of the HVAC systems of these sites. However, it can be demonstrated that even with a normal background of PM2.5, concentration infiltration might be a concern.

THE OUTCOME Although this study had a limited number of monitoring sites, it did indicate that there appears to be a higher risk for the periphery zone to be impacted by wildfire smoke particles due to the increased infiltration it experiences. Consequently, mitigation strategies should include a focus on reducing infiltration. The combined results of the online survey and on-site monitoring reveal a need for additional control approaches to address prolonged periods of wildfire smoke.

The NRC is currently in the planning process for further projects to evaluate the effects of wildfire smoke and technologies to reduce its impact.

Greg Nilsson is a lead technical officer and project manager for the indoor air quality group of the Construction Research Centre at the National Research Council. He is also the current chair of CSA Group standard C22.2 No. 187, Electrostatic Air Cleaners. Greg’s expertise is in the area of measuring airborne contaminants, experimental and equipment design. He can be reached at greg.nilsson@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Emerging infectious diseases are infections that have recently appeared within a population and can be caused by previously undetected or unknown infectious agents, or the emergence of new pathogens. 1

In the news.

As of January 31, 2020, there have only been four confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Canada (three in Ontario and one in British Columbia). 2 The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is working with Ontario and international partners, including the World Health Organization (WHO), to actively monitor the situation. Currently PHAC has assessed the public health risk associated with 2019-nCoV as low for Canada. Public health risk is continually reassessed as new information becomes available. 2 On January 30, 2020 WHO declared that the outbreak now meets the criteria for a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. 3

Coronaviruses (CoV) are a family of enveloped viruses that were first discovered in the 1960s. Coronaviruses are most commonly found in animals, including camels and bats, and are not typically transmitted between animals and humans; however, six strains of coronavirus were previously known to be capable of transmission from animals to humans, the most well-known being Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) CoV, responsible for a large outbreak in 2003, and Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) CoV, responsible for an outbreak in 2012. 4 Dr. Alison McGeer, infectious disease specialist at Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, said the fact that cases are being found in other countries suggests that screening systems are working and that is good news about the work underway to prevent a wider SARS-like outbreak. 5 There have also been cases of person-to-person transmission outside of China. 3

How does it spread?

Coronaviruses are typically spread through the air via coughing or sneezing, via contact with an infected person or contaminated surfaces, and sometimes, but rarely, via fecal contamination. 6 2019-nCoV is thought to have originally spread from animals to humans. There has been limited person-to-person spread of 2019-nCoV. At this time, there is no clear evidence that this virus is spread easily from person to person. This pattern of transmission was also reported with SARS CoV and MERS CoV. 7 PHAC has also issued an information sheet on 2019-nCoV. 8,9

Protection is paramount.

WHO has declared the novel coronavirus as a public health emergency of international concern. 3

When the PHAC issues a public notice that an emerging viral pathogen poses a significant risk to Canadians or has been declared by the WHO as a public health emergency of international concern, manufacturers can communicate to the public about non-label efficacy of some currently available disinfectants against emerging pathogens, such as 2019-nCoV. 10

PHAC recommends the following infection control and prevention strategies to prevent or limit transmission of 2019-nCoV in healthcare facilities – prompt identification, appropriate risk assessment, management (including promotion of adherence to hand hygiene, use of personal protective equipment, etc.), placement of probable and confirmed cases, and investigation and follow-up of close contacts. 11 PHAC also has additional information on prevention and risk from 2019-nCoV and an information line (1-833-784-4397). 2

Plan to protect.

Under conditions of a public health emergency of international concern declared by PHAC or the WHO, Health Canada permits disinfectants to make non-label efficacy claims against the emerging viral pathogen if they have a broad-spectrum virucidal claim or for emerging viral pathogens or for which the taxonomic genus of the virus has been identified, efficacy data against other viruses within that genus may be considered acceptable (e.g., any coronavirus for a claim against the novel coronavirus, 2019-nCoV). 10 The following Clorox® products all have a broad-spectrum virucidal claim and demonstrated effectiveness against coronaviruses. These products are expected to be effective against 2019-nCoV when used as directed: 12

• Clorox Total 360® Disinfectant Cleaner • Clorox Healthcare® Spore Defense™ • Clorox Healthcare® Bleach Germicidal Wipes • Clorox Healthcare® Fuzion™ Cleaner Disinfectant • Clorox Healthcare® Germicidal Disinfecting Cleaner • Clorox® Germicidal Bleach

References: 1. Emerging infectious disease. Baylor College of Medicine. https://www.bcm.edu/departments/molecular-virology-and-microbiology/emerging-infections-and-biodefense/emerginginfectious-diseases. Accessed January 19, 2020. 2. 2019 novel coronavirus: Outbreak update. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html. Accessed February 4, 2020. 3. WHO declares coronavirus outbreak an international emergency. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/who-reconvenes-assess-latest-coronavirus-1.5445775. Accessed January 30, 2020. 4. About human coronaviruses. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/about/index.html. Accessed January 31, 2020. 5. Key things to watch for in the coronavirus outbreak. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/coronavirus-china-canada-questions-1.5433986. Accessed January 22, 2020. 6. Transmission. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/about/transmission.html. Accessed February 4, 2020. 7. 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation summary. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/summary.html. Accessed February 4, 2020. 8. 2019 novel coronavirus. Public Health Agency of Canada. https://www. canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/diseases-conditions/2019-novel-coronavirus-information-sheet/coronavirus-handout-eng.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020. 9. Novel coronavirus infection: Frequently asked questions (FAQ). Public Health Agency of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/ frequently-asked-questions.html. Accessed February 4, 2020. 10. Health Canada Guidance Document: Safety and efficacy requirements for hard surface disinfectant drugs. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/applications-submissions/guidance-documents/disinfectants/safety-efficacy-requirements-hardsurface-disinfectant-drugs.html#b5. Accessed January 27, 2020. 11. 2019 Novel coronavirus: For health professionals. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/ diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/health-professionals.html#i. Accessed February 5, 2020. 12. Data on file. The Clorox Company.

Protection you can’t see.

Everyday sporicidal protection now available for the Clorox Total 360® system.

In addition to our current line of disinfection formulations and products, CloroxPro™ offers a new Spore Defense™ formulation, exclusively for the Clorox Total 360® system. This powerful new chemistry is Health Canada-approved to kill: ♦ C. difficile in 5 minutes ♦ 42 out of 47 pathogens in just 1 minute, including MRSA, VRE, measles & polio Clorox Total 360® system with Spore Defense™, when used regularly, provides your facility with invisible yet effective outbreak prevention. In addition to our current line of disinfection formulations and products, CloroxPro™ offers a new Spore Defense™ formulation, exclusively for the Clorox Total 360® system. pathogens in just 1 minute, including MRSA, VRE, measles & polio Clorox Total 360® system with Spore Defense™, when used regularly, provides