INTERVIEW

34

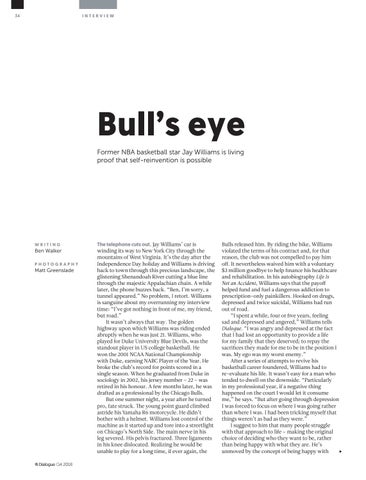

Bull’s eye Former NBA basketball star Jay Williams is living proof that self-reinvention is possible

WRITING

Ben Walker PHOTOGRAPHY

Matt Greenslade

Dialogue Q4 2018

The telephone cuts out. Jay Williams’ car is winding its way to New York City through the mountains of West Virginia. It’s the day after the Independence Day holiday and Williams is driving back to town through this precious landscape, the glistening Shenandoah River cutting a blue line through the majestic Appalachian chain. A while later, the phone buzzes back. “Ben, I’m sorry, a tunnel appeared.” No problem, I retort. Williams is sanguine about my overrunning my interview time: “I’ve got nothing in front of me, my friend, but road.” It wasn’t always that way. The golden highway upon which Williams was riding ended abruptly when he was just 21. Williams, who played for Duke University Blue Devils, was the standout player in US college basketball. He won the 2001 NCAA National Championship with Duke, earning NABC Player of the Year. He broke the club’s record for points scored in a single season. When he graduated from Duke in sociology in 2002, his jersey number – 22 – was retired in his honour. A few months later, he was drafted as a professional by the Chicago Bulls. But one summer night, a year after he turned pro, fate struck. The young point guard climbed astride his Yamaha R6 motorcycle. He didn’t bother with a helmet. Williams lost control of the machine as it started up and tore into a streetlight on Chicago’s North Side. The main nerve in his leg severed. His pelvis fractured. Three ligaments in his knee dislocated. Realizing he would be unable to play for a long time, if ever again, the

Bulls released him. By riding the bike, Williams violated the terms of his contract and, for that reason, the club was not compelled to pay him off. It nevertheless waived him with a voluntary $3 million goodbye to help finance his healthcare and rehabilitation. In his autobiography Life Is Not an Accident, Williams says that the payoff helped fund and fuel a dangerous addiction to prescription-only painkillers. Hooked on drugs, depressed and twice suicidal, Williams had run out of road. “I spent a while, four or five years, feeling sad and depressed and angered,” Williams tells Dialogue. “I was angry and depressed at the fact that I had lost an opportunity to provide a life for my family that they deserved; to repay the sacrifices they made for me to be in the position I was. My ego was my worst enemy.” After a series of attempts to revive his basketball career foundered, Williams had to re-evaluate his life. It wasn’t easy for a man who tended to dwell on the downside. “Particularly in my professional year, if a negative thing happened on the court I would let it consume me,” he says. “But after going through depression I was forced to focus on where I was going rather than where I was. I had been tricking myself that things weren’t as bad as they were.” I suggest to him that many people struggle with that approach to life – making the original choice of deciding who they want to be, rather than being happy with what they are. He’s unmoved by the concept of being happy with