25 minute read

Feature

from Aug. 28, 2014

THIS IS THE FOURTH INSTALLMENT IN OUR YEARLONG PROJECT LOOKING AT THE ISSUE OF FATAL ENCOUNTERS BETWEEN LAW ENFORCEMENT AND PEOPLE.

darren Wilson, the Ferguson Police Officer who shot and killed Michael Brown, the unarmed African-American teenager in the St. Louis, Missouri, suburb has received a ration of hate from around the country.

Advertisement

And he may be the only person in the country who knows whether it’s deserved. It’s certainly not as black and white as it was presented in the early rush of reportage.

ABC News reported this exchange on Aug. 19 from an anonymous friend of Brown’s: “The whole situation is a tragedy for both Michael Brown and his family, and Darren and his family,” Brown’s pal said. “Both of their lives are ruined. I can tell he’s struggling. I can tell this is really hard on him. He’s been very careful about who he talks to, so he hasn’t spoken much about the situation.”

Reno Deputy Police Chief Byron “Mac” Venzon suffered similarly after killing a person in the line of duty, though he didn’t have the hate of 50 million people to compound it.

“I was working in undercover capacity, and we had information that a subject, a recent prison release, was up here stalking and trying to lure away a young girl that he had communication with in the past,” he said. “He had become involved in a shooting with a California agency on the way here. We learned of his whereabouts, set up a surveillance, and once we knew he was there, we set up kind of a perimeter. He came out, presented a weapon at me—from me to you away from one another [about four feet]—he presented a weapon to me and then I had to shoot him, and he died.”

It was as clean a killing of a known criminal as we ever hear about—cop faced with a gun kills the guy who’s wielding it to protect himself and others. And yet, there is no amount of training that can prepare an officer for the psychological and social repercussions, and Venzon ought to know, having worked as a staff officer at the police training academy and 16 to 17 years in a variety of law enforcement assignments.

“You know you go through a whirlwind of emotions, and as much as you try to prepare for that, until you are there, I know that you can’t,” he said. “Your safety was very, very tenuous at that time, right? So you start to do this whole flashback of ‘I have a kid, what about this? What about that? What will it do to my family?’ And then you start to realize that, ‘Wow, this person put me in a position where I had to do something that I didn’t relish the idea of doing.’ It wasn’t something I set out to do. I think you could talk to every officer in this department, and they will tell you that their preference is that every incident ends peacefully, and you know it’s tough—tough at home, it’s tough on my family. You always worry about civil litigation after that, and there is nothing you can do to stem off the civil litigation that comes from that, so you sit around two years and one day waiting for the civil litigation to come.

“It’s a lot of emotion you go through, and it takes some time, and I think what you find out is that you don’t know how you are going to react, and you don’t know how long it is going to take you to get over it.

He says he’s over the experience now, but there was an unexpected catch in his voice when he said so.

“The way it has been described to me, when you can talk about it and not feel the emotion, then you know you worked your way past it,” he said. “And so there was some offers of, you know, help with the counselor, and I took up some of those. Those were fantastic, and so it took me about probably six months before I could sit and discuss it with you and not feel emotional about the whole thing.”

Sentiments like those are echoed across the nation by officers who’ve had to face that fatal moment. But it’s hard to get some to talk about it—that blue wall that people talk about, that police belief that non-police simply can’t understand what they go through.

Still, there’s a commonly understood phrase to describe what happens to an officer who kills in the line of duty: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD.

And in Northern Nevada, there are people to help. While primarily a sports psychologist, Dr. Dean Hinitz has helped out on officer-involved

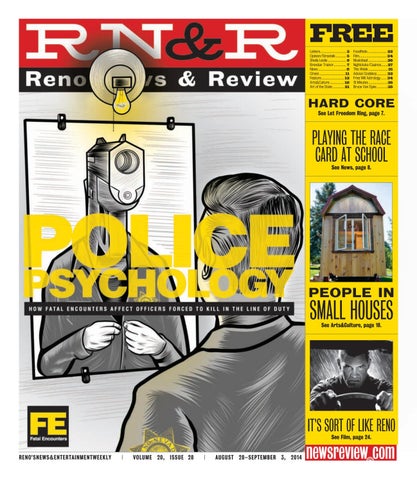

written BY d.BrIan BurGHart illustrations BY JonatHan BucK design BY BrIan BrEnEMan

How Fatal e ncounters a FF ect o FF icers F orced to kill in t H e line o F duty

killings for years. He’s a former member of the Nevada Board of Psychological Examiners and was chief of psychology at West Hills Hospital. In his private practice, he specializes in life change issues, like anxiety and depression, and relationship concerns. Dr. William Danton is the former associate chief of staff for mental health at the VA Sierra Nevada Health Care System and is a clinical professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Nevada School of Medicine. While his focus is in many ways still about veterans, the emotional challenges suffered by officers who’ve had to kill people in the line of duty are similar to that of soldiers, and he’s helped out with many officer-involved deaths. Reno Police Chief Steve Pitts also mentioned Trial Science, but Dr. Dan Dugan declined an interview, saying he doesn’t discuss clinical issues with the media.

IsolatIon, IntrusIon and dIsassocIatIon

Dr. Hinitz sits comfortably in his intimate office on treelined Humboldt Street in Midtown. He looks a little like a police officer, with carefully cut hair, fit physique, and the somber, steady gaze of someone who’s thinking carefully about the words that are being said. He’s got road rash on one forearm from what looks like a mountain bike crash. There’s a gentle ticking of a clock that both modulates and propels the conversation forward. The topic is anything but gentle, though.

“It’s a rocking event, and I don’t mean that in a cool way. I mean that in terms of ‘really rocks the boat’,” he said. “The sequelae [emotional consequences] have been profound for the individuals that I’ve worked with almost to a man, which is the profundity of taking a human life, the unexpected jolt of how hard it is and the meaning of it when oftentimes they’ve not known ahead of time the sorts of things that it was going to bring up.”

Even for those who are experienced and trained, there is something about taking a human life that is more than just “real,” but a psychological sea change that can shake an officer to his or her core.

“I’ve known very few who could have been prepared for what happened, and they were all trained,” Hinitz said. “The two cardinal features are sort of an alternation between sort of hyper-arousal and intrusion where thoughts of it and memories of it and cycling through it repeatedly alternate with distancing and disassociation. It sounds like these competing forces of ‘You’ve got to work this through,’ and ‘You’ve got to metabolize this,’ against ‘You’ve got to get away from this nightmare’.”

Hinitz said there are basically three stages in the healing, although he’d be quick to say that to narrow it down this far tends to diminish the complexity of individual reactions.

The first stage is distancing, kind of a psychological numbing that follows closely after the event. It makes the moment hard to remember clearly, a sort of pain reaction.

“The second stage is the stage where you—if you’re going to be involved in recovery process—where it’s a stage of narrative. So you’ve got hyper arousal [which is a high mental alert stage], you’ve got intrusion and numbing followed by some form of remembrance and mourning, which is, ‘I’ve got to get the sequence right.’ There’s no shortcut. It’s got to be metabolized.”

Third stage is reconnection.

Hinitz talks about the importance of that time off, the paid administrative leave that people on the outside seem to think as a rewarded vacation. But a moment’s thought about how people suffering with PTSD act, and there’s no question that a logical person does not want that officer on the street with a gun.

“I think it’s one of the most sensible policies there is because either somebody’s going to be prone to threat immediately after until they’ve worked it through or if they’re going to be prone to avoidance, over-avoidance in situations where they would need to be more reactive right away. ... And despite people’s appearance and despite the bravado sometimes of the role, I’ve never seen

You know You go through a

whirlwind of emotions, and

as much as You trY to prepare

for that, until You are there,

i know that You can’t.

BYron “Mac” VEnzon

rEno dEPutY PolIcE cHIEf

one that didn’t review and go, “Did this have to happen? Was this OK? Was this necessary?” So it has to be examined at a level of meaning. … And the repetition, the review and the emotional involvement is letting the brain sort of prepare and get ready for future events that could occur. And without that processing, as we said, you either have over-avoidance or over-involvement.”

But the utility of the time off is possibly the one area in which Dr. Hinitz and Dr. Danton slightly diverged in opinion. There must be some kind of acceptable medium, because time off tends to isolate the officer when he most needs his support system, his fellow officers.

Misconceptions and adjustMents

“I think in police work, one misconception is that people that get into that have a value system that’s kind of assertive, directing and authoritarian, and they like the authority and so forth,” said Dr. Danton.

Danton’s office is more collegiate than intimate. It looks sort of like you’d expect from somebody high up in a university’s administration, except it’s in one of those labyrinthine complexes that would make a well-adjusted person pull out his or her eyebrows.

His office, again, is calming, but large enough for a small group session. Danton himself is also academic, dressed more casually than business-casual with a rumpled, nonthreatening, friendly feel. He’s a sincere helper, passing along emails of related information after the interview concludes.

“The primary value system of a lot of cops going into police work is being a member of a team,” he said. “And so one of the things that happens when you’re involved in a shooting event, use of deadly force, is you get put on administrative leave, and you get your gun and your badge taken away, and you get separated from the team. That’s not always a good thing, and a lot of cops will say that separates you from your support group. Some of these guys don’t go home and talk—many of them don’t go home and talk to their families—about what they do. So it’s a very isolating kind of event and sometimes that makes the PTSD worse because you don’t have anybody to share it with.”

So sometimes, that paid vacation can exacerbate the problem.

“Sometimes it does,” Danton said. “Think about the primary value system with being one of and belonging to a team. … You’ve got somebody who’s involved in use of lethal force, and they go home. Their family doesn’t really understand what’s going on, and the people who would understand, they’re isolated from. And

there’s almost a pariah effect, I think, when somebody’s on admin leave. A lot of guys have complained to me that their usual friends and cohorts kind of leave them alone during that period of time.” The key during the times immediately following a fatal encounter is a concerted effort on the part of the individual, police administration, families and friends, to get the individual past the traumatic incident. And that’s where guys like Hinitz and Danton come in. Danton says his strategy varies with the individual. He first looks at what skills and tools they have when they walk in the door. How do they typically handle stress? “Part of it is remapping the idea of avoidance and exposure,” he said. “In anxiety reactions, there are three components: There is an uncomfortable body sensation of some kind, there is an avoidance of trying not to feel that uncomfortable sensation, and there is what I call ‘anticipatory incompetence.’ The person anticipates they won’t be able to deal with it, and they’ll go crazy or fall apart or have a heart attack or something.” Psychiatrists and psychologists have a specific and arcane language they use, like most practitioners of specialized activities. Dr. Danton is particularly adept at using a word and then bringing it down to us hobbyists. “Almost all therapies for anxiety-related disorders are at the bottom line exposure therapies. You want to have the person be exposed “I’ V e k NOWN V e RY F e W and not have that [negative] reaction. EMDR, WHO CO ul D HAV e B ee N the Eye Movement Desensitization and p R epAR e D FOR WHAT Reprocessing, is a kind of therapy that has the HA ppe N e D, AND TH e Y person re-imagine the traumatic event and W e R e A ll TRAIN e D,” what kind of unconstructive cognitions did they have about the dean Hinitz event at the time like, psYcHoLoGist ‘Oh, I was an idiot. I did the wrong thing.’ And then they’ll have the person re-imagine the scene, and then you’re reconnecting them with the event and having them come up with something more positive like, “I can handle this. I did the right thing.” Something like that. So you’re remapping. You’re creating a new map.” Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is also used. It relies on the idea that it’s not the event that causes the problem. It’s the meaning of the event for the person. The person must remap it in a way that’s more productive for them, that helps them feel healthier about the event. Group therapy can be effective in seeing that other people have been through the same thing and have coped with it and are OK with it. Part of the problem with this is simply coming up with a group of police in any region who’ve killed somebody. Educating families is another crucial task:

Head wounds

In some weird parallel universe, there’s a Venn diagram waiting to be made. In it, you’d have three circles: psychologists, people who work with police, and family members of people killed by police.

In that dark spot where all the circles overlap—family members of people killed by police who work with police— there would be one name: Steven Ing of Reno.

Ing is a marriage and family therapist, who, almost as a primary job, works with sex offenders who for one reason or another are involved in the Nevada prison system. He believes they can be rehabilitated, an unorthodox view. But maybe growing up as the child of a notorious Reno thug, Jimmy Ing, you’d have to believe anyone can be rehabilitated—at least until they are killed by police.

Ing would certainly have a unique perspective on the effects on families of people killed by law enforcement. He’s singular in many ways. He’s a financial success after a childhood where he’d lie in bed, screaming with a pillow over his head while his father beat his mother. His father was bad, bad. He was reputed to have beaten a man almost to death and then finishing the job by putting him in a metal barrel, pouring oil over him and setting him on fire.

Ing said that he didn’t even begin processing the 1966 or ‘67 police “execution” until he was 19. According to the cuddly Mustang Ranch brothel owner Joe Conforte, writing in his book, Breaks, Brains & Balls, law enforcement set Jimmy Ing up at a West Fourth Street motel. “There must have been at least 20 cops waiting with shotguns. As soon as Jimmy comes out, ‘Freeze!’ They didn’t even wait two seconds. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. He had 22 bullet holes in him.”

“We had a boarder living with us at that time, and she said, ‘You need to take care of your mom,’” reminisced the 60-could-pass-for-50 psychologist Ing. “And I just switched channels from any kind of processing to taking care of my mom, which was the beginning of a lifelong pattern of co-dependent, rescuing women—damsels in distress—and resulting in my first marriage.

“I’m able to trust Sharon [his wife] today, but when I was 20, the irrational thought in my head, the belief was, ‘I’m all I’ve got to count on,’ because there’s some dramatic shift in a guy’s thinking [when cops kill his father]. I was raised in that school generation where they always talked about Officer Friendly and how you could trust the police and all of that, and they have the good guys beat the bad guys. [The killing is] a total flip flop of your paradigm, and I remember when I was in my teens, I think I was 18, a high school teacher was under investigation, and the DA asked me to come by his office to be interviewed because I knew something about it, and I took a friend because I wasn’t sure I was going to live. That’s how it affected me. I really had this irrational fear of death because the police had killed my dad and it was this sense of ‘Well, then, nowhere is safe because if you can’t trust the police then really, nothing is real.’”

Ing says that maturity is usually a function of time and experience, but acting quiet and controlled doesn’t ensure maturity. He said that at 12 or 13 he felt “super mature,” but at 30, he realized he was no more mature than when he was 13. So the psychological effects of his father’s killing included stunted emotional growth, paranoia, dysfunctional marital choices, inability to trust others, and difficulty in forming cooperative partnerships with people for any reason. “I’m not going to say every bad thing in my life is a result of my father’s getting shot, but it is true I believe that everything in my life is related to every other thing, and most all of these bad things do have some sort of root in my father’s death and the way he died,” Ing said. “Janet Reno said that domestic violence is the root of all crime in America, and I think it really makes sense because there’s that complete and utter violation of boundaries with the people who supposedly you love and care for the most, and if I love and care for my family, and I can hit them, why would I not hit somebody else, right?

“And the police killing your dad is a similar sort of violation of those boundaries. I have the honor of working with a lot of law enforcement today, and I really admire and respect those guys who do what they do, but I am also very aware of how human they are and that they too have their issues.”

Steven Ing

House of pain

Kenny Stafford came back from Iraq a changed man. He was never to heal, though, as he was killed by police on July 11, 2013.

The once social and gregarious man that Aimee Stafford met in ninth grade was withdrawn, didn’t want to hang out with friends. The caring, funny and strong warrior didn’t want to listen to music—he used to like everything but country— didn’t want to read his favorite fiction by the likes of Stephen King and Dean Koontz, didn’t want to watch sports; the joy seemed drained from his life.

“He was trying to adjust back into civilization, and I figured he had saw and done some things over there that are probably hard to get past, so I just wrote it off as that,” said his widow, Aimee. “But then when we got transferred to Fort Lewis, Washington, that’s when he started losing a lot of weight. He couldn’t sleep. He wouldn’t eat. He would get agitated a lot, and he lost 65 pounds in six months.”

Kenny didn’t even want medical attention. His petite and pretty wife had to pester the 6-foot-3 soldier until he finally consented to see a doctor.

“They said he was depressed and put him on medication for that, and then they were doing some other things for PTSD,” she said. “And then we came up here to Reno for my brother’s year anniversary, and he was OK until the night of the anniversary of my brother’s murder.”

It’s a close-knit family, various races and combinations, but when somebody says brother or son, they’re not necessarily talking by blood. They’re just all so close they naturally call themselves by those names that are usually reserved for people who came from a single womb.

“Ryan [Connelly] was killed July 7th, 2012,” said the family matriarch Deana Crook. “He was murdered, and Kenny was very upset about the killer still running loose. He was angry about that. He was angry that they weren’t doing anything. He was very angry about all that.”

Connelly was killed in what has been theorized as a case of mistaken identity by a gangmember. The killer remains at large. Over the four days after the anniversary of his brother’s death, Kenny Stafford kept disappearing, so many times Aimee couldn’t count them. She was frantic, not knowing where he was. She only knew he was disturbed. “He started asking around for a gun,” said Crook. “He asked my son—his brother—was asking him, ‘Hey can you get me a gun?’ And my older son said, ‘No. What do you need a gun for?’ And he said, ‘For protection.’” Even after a year, it’s hard to sit with these women in the small apartment off Wedekind Road, as they discuss their twin tragedies. Ryan’s ashes rest in a footballshaped urn on the end table between them. His photo perches upon it. “I went over to check on Aimee that morning, the day he was killed,” said Crook. “I went over there, and I said, ‘Is everything OK?’ She says, ‘No, he’s acting strange. I don’t know what’s wrong with him. I’m worried. I’m worried. I’m worried.’ They called the VA to see what they can do. ‘Can you get him some help?’ They said, ‘Since he’s not with us—his stuff is in Washington—we don’t know what we’re going to have to do. You’re going to have to bring him down here.’ Aimee’s like, ‘Do you understand he’s not going to come? Can’t we do something to bring him in there?’ And they told her, ‘No.’’’

It was not long before Crook got a call from her best friend, Aimee’s mother, “Kenny’s got a gun.” The desperate Crook rushed down to Wedekind Road, but the police stopped her at the barricade. Only she and Aimee could talk Kenny out of his PTSD fugues, and the cops wouldn’t let her through. Frantic, she drove all the way around Clear Acre to McCarran then all the way down to El Rancho and then came back around to the other end of the blockade. Again, the police would not let her approach her son.

But then the Washoe County sheriff’s helicopter arrived, worsening his PTSD state with memories of Iraq, Crook surmised. The helicopter was setting him off. “I knew that was going to be bad,” she said. “Well, he turned and asked for a cigarette. So one of the cops says, ‘He wants a cigarette.’ And I’m thinking, ‘OK, good, good, good.’ I said, ‘See that little thing that he was talking on? Give me your microphone. Just let me talk to him. He’ll listen to me. He’ll snap out of it. He’ll know that he’s not in Iraq.’ He’ll go, ‘What the fuck—what’s mom doing in Iraq?’ He’s going to understand. He’s going to know. “They said, ‘No, ma’am we can’t do that.’ And they were assholes, they were rude. They were obnoxious and they’re telling us, ‘We know he’s sick. We know. We know.’ And they’re— they’re looking at you like you’re just ... ‘His role in Iraq, we know. We know.’ “And I’m like, ‘Well, if you know, please don’t hurt him.’ So just as we got the cigarette, gave it to the one officer, the other officer gives it to another, and they open fired on him. “He never got the cigarette.” She believes he was never a threat to anyone: “Not even to himself. Not even himself. He never fired the gun once. They shot 22 rounds at him and hit him, was it 15, 16, 15 times. Head shots, too.”

“Seven, to be exact,” adds Aimee.

Few outside this close-knit family would question police putting down a mentally ill man with a gun. Anniversaries and birthdays have come and gone. Kenny Stafford would have turned 29 on August 17. Ryan Connelly was killed more than two years ago. Kenny’s wife and mother-in-law believe the police have a suspect in Ryan’s murder, but they also believe the cops are doing little. While they wait for some kind of closure, the women spend their time on Facebook, posting photos of their lost men, promoting their Justice for Ryan and Justice for Kenny pages, and wondering just how much pain one family is supposed to take.

Aimee Stafford, left, and Deana Crook sit in the family room with Ryan Connelly’s ashes in a football-shaped urn between them. Kenny Stafford was upset about the murder of his brother. Kenny was killed by police on July 11, 2013.

Photo courtesy stafford family

— D. Brian Burghart brianb@ newsreview.com

FROM page 15

For some families, their husband or wife was a hero, and they’re the one that handles all the stress. And now the hero is messed up, and they’re wanting support. It is, as Danton said, a role reversal.

“So then the police officer is uncomfortable in a non-traditional role,” he said. “They’re not the protector of the family now; they’re somebody who is in need of protection from the family. You got kids, how do you go to take your kid to soccer, and you got all these people running around and doing stuff, how can you feel safe? What do you do? How do you protect your kid in that situation?”

Both doctors said that the cliched movie stereotypes of police drug addiction or alcoholism, domestic abuse or divorce are not more prevalent after one of these events. Cops have high divorce rates without having to kill someone. In fact, in these really overwhelming events, they tend more toward shielding their spouse and children, which is why family counseling is so important. It’s really all about healing the PTSD.

“The policy is part of that, and I think also really understanding PTSD and how do you deal with cops involved in these things because people I have seen would have liked a much higher level of support. A lot of cops, interestingly enough, involved in these situations, they’re really good guys. They feel sometimes betrayed by the administration and so forth. They don’t like hypocrisy. They’re really black and white thinkers sometimes about those kind of things. And that’s hard on them.

“We could do better. We could show them our support and not that kind of support of ‘Let’s all lock arms and not let reporters know what’s going on with the situation.’ But support like ‘You’ve been through a trauma, and you still belong to this group, to this team, and if you made the right calls on this, we’ll support you on them. If you didn’t, we’ll try to understand that, but you still have to pay the consequences for it’.”

After the news crews and the National Guard leave that little suburb of St. Louis, Missouri, the Ferguson Police Department is going to have to deal with these issues. Whether Darren Wilson turns out to be a courageous warrior caught up in a circumstance beyond his own making, or the racist murderer that so many have made him out to be, the entire U.S. is going to have to deal with these issues. Ω

T HERE ’ S ALMOST A PARIAH EFFECT, I THINK ,

WHEN SOMEBODY ’ S ON ADMIN LEAVE . A LOT

OF G u YS HAVE COMPLAINED TO ME THAT

THEIR u S u AL FRIENDS AND COHORTS , KIND

OF LEAVE THEM ALONE .