7 minute read

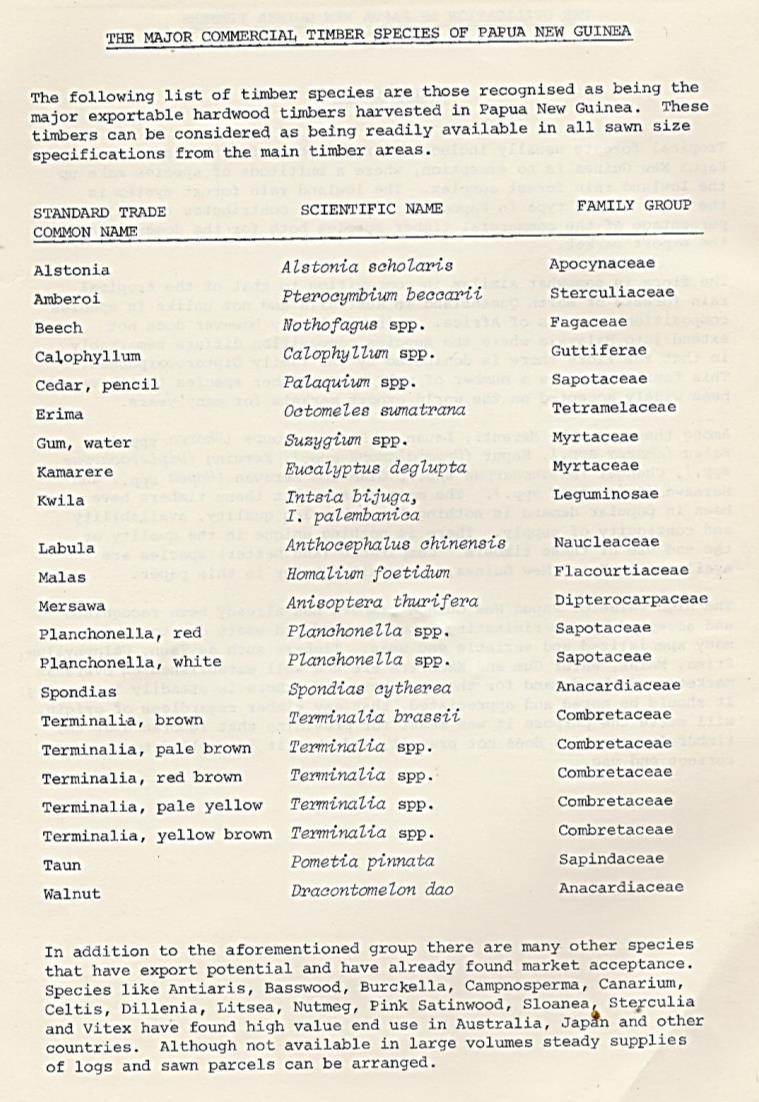

Merchantable and Non-Merchantable Species

from PNGAF MAGAZINE ISSUE # 9D 2 of 15th October 2021 THE DEVELOPMENT OF PNG'S FOREST MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

by rbmccarthy

Merchantable and Non-Merchantable Species.

Any development scheme based on forestry, which must perform long term, is prepared on the forester's appraisal of the forest, how to treat and manage the forest, and on the forester’s assessment of the type and quantities of products that one would expect to obtain within a sphere of where only several merchantable species are acceptable on international markets.

Advertisement

It has been shown that a very common feature of rainforest is the complexity of its floristic composition. Rainforest stands can contain more than 100 different species of woody shrubs and trees per hectare. From a management viewpoint, those species can be broadly classified as those which are merchantable and those which are non-merchantable.

Merchantable species are species which, when of suitable size and form, can be sold as timber products by the forest owner for monetary gain.

17

Non-merchantable stems (when of suitable size and form) are those whose properties are unknown to potential purchasers, or their stocking is too low to permit the collection of commercial consignments.

17 Eddowes P J 1979. The Utilisation of Papua New Guinea Timbers. FPRC Dept of Forest Port Moresby PNG. P2.

Much work is required by forest product laboratories to firstly study each non-merchantable species, determine its properties, and then market its timber products so that its most desirable properties can be utilised.

Often, the lesser-known species are first marketed as substitutes for species already well established on global markets. e.g., the West African export market has seen the phenomenon of Chlorophora being introduced into world markets as a substitute for teak (Tectona spp), then being established in the marketplace. Finally, there has been the species Piptadeniastrum being placed upon the market as a substitute for Chlorophora.

18

Similarly, many common names are given to rainforest trees comparing them to European species as elm, beech, oak, ash etc. without having any botanical relationship to the European trees bearing those names.

18 Eddowes P J. 1979. The Utilisation of Papua New Guinea Timbers. FPRC Dept of Forest Port Moresby PNG. p5.

Low quantities of an individual species are a serious drawback to the development of export markets. Because of the problems of inadequate volumes, the forester aims to grow large quantities of a useful species rather than aiming to grow a few scattered and low representative species.

Previously, inaccessibility was a common cause of a species being non-merchantable. This arose because of the cost of log transportation from the remote forest area. Where the extraction and transportation period are long, there is increased risk of degrade from insects and fungi.

In more recent times, improved methods of protecting timber from degrade and more road transportation methods, have reduced the risk of degrade.

Merchantable and non-merchantable species are essentially determined by economic factors. Market forces, scarcity of wood fibre, improved harvesting methods and other technological advances in time may well result in more species becoming economic.

Poorly controlled harvesting operations can be a major cause of damage to the remaining stems in the rainforest. Because of this issue, logging codes of practice have been developed to ensure reduced impact of logging operations on the residual stands of the rainforest.

By the 1990’s several procedures had been developed to ensure better harvesting and protection of the residual rainforest stands and protection of watersheds.

The role of forests in protecting watersheds has generally been recognized in traditional PNG culture and forests in river catchments have not been disturbed in many traditional communities in the country for many years. Forests have also been recognized and respected as providers of other goods and services. Respect for forests, especially those present in watersheds, is partially embedded in the spiritual and cultural norms of the tribal people. These forests are thought to be places where the spirits dwelled and hence have often been left alone. Fear of enemy tribes also restrained many communities from venturing into water catchment areas, as they are often isolated areas.

The Government having recognized the significance of catchment areas has ensured that they are protected. In particular, the forest policy, forestry laws and regulations and operational manuals such as the PNG Logging Code of Practice provide specific guidelines on their protection. The Environmental Act also makes provisions for the protection of catchment areas.

Page 6 of the first edition (April 1966) of the Logging Code of Practice delineates that all conditions imposed by the PNG logging code of practice will be in compliance with requirements of:

• Forestry Act 1991 as amended. • Environmental Planning Act Chapter 370. • Water Resources Act Chapter 205. • Environment Contaminants Act Chapter 368. • Conservation Area Act 1978. • Investment Promotions Act No. 8 of 1992. • Public Health Act Chapter 226 and its regulations (Drinking Water 1984). • PNG labour Law, Industrial Safety Health and Welfare Act Chapter 175 and its orders and regulations. • Land Transport Board Act as amended No. 11 of 1991. • Civil Aviation Act Chapter 239. • Public Works Committees Act Chapter 28. • Land groups Incorporation Act Chapter 147. 19 The Acts described above are binding on all parties and individuals involved in selective logging in PNG.

19 The Papua New Guinea Logging Code of Practice was formally adopted by the National Executive Council in March 1996.

There are many key factors that affect the economic viability of the forests of PNG. These include, but are not limited to the following:

• Global and regional market forces. The demand and supply of wood and wood products including pricing has an impact on the economic viability of forest management. High demand coupled with high prices, especially for round wood logs, encourages forest operators to produce more wood – sometimes at the expense of good management practices. The economic crisis of 1997 saw log prices plummet, forcing many logging operators to close business. It also led to significantly lower foreign exchange earnings for the country. • High species diversity. The highly diverse species mix in PNG’s natural forests can pose certain operational problems. Forest-based industries are often not able to meet their market quota for a desired species and sometimes must gather logs from different operation points in the country. In many forest concessions, no single species constitutes more than 5 percent of the total growing stock. This leads to large volumes being exported in mixed species parcels, thereby fetching lower FOB prices, especially in Asian markets. • Low stand density. Forests in PNG have a lower stand density in comparison to other countries in the Asia region. This increases operational costs to extract timber and requires that larger areas be harvested to meet market commitments. Extraction of smaller size logs is often resorted to, which ultimately impacts the prices received in the export markets and, more importantly, the sustainability of forest management, considering that the trees that have been removed would have constituted the crop in the second cutting cycle. • Remoteness of timber concession areas. This creates a concern for logging operators as they must pay higher costs for mobilizing and supplying goods and services to the logging sites. In addition, the remaining forest areas that have potential for forest logging operations are located even further from established urban areas with little or no road or other forms of access. To access these resources would require much capital input from the proposed developers. • Increasing cost of fuel. This has been estimated by some industry sources to constitute more than 50 percent of the operational costs for some projects. • Lack of enabling environment by the Government. This includes issues such as current tax regimes, incentives to improve downstream processing, adequate resource supply, resolution of landowner disputes, and so forth.

Overall forests in PNG have played a significant role in the economic development of the country and will continue to do so for the next decade. Unfortunately, there are fewer areas now that are available for logging operations.

The main key issue in undermining SFM in PNG is compliance by the timber industry to forestry laws, regulations, and procedures. Destruction of residual tree crops and the unwarranted damaging of soils and saplings through large disturbance are some of the issues that will affect sustainability.