We didn’t solve the mystery of drinking from the Old Well in this issue.

Every semester, on the eve before classes start, undergraduates line up to sip from the fabled Carolina landmark. It’s not unusual to find hundreds of students lined up at midnight, and with good reason. Allegedly, taking a drink from the Old Well provides—depending on who you believe—good luck or straight A’s.

Solving that riddle—along with what, exactly, happens at the Castle at Gimghoul—are two of the biggest myths on campus at the University of North Carolina. We’ll leave those for future historians.

But in this issue, we wanted to investigate some of the biggest Tar Heel sports legends. In the following pages, you’ll find the answers (or at least valiant attempts at the answers) at such pressing issues as when the Bell Tower is lit blue, how exactly to pronounce the word Boshamer (it’s not what you think!) and whether you can take a ferry from the Outer Banks to Chapel Hill.

OK, you probably already know the answer to that last one. But so do the co-creators of the show that made that particular route famous. They’re Tar Heels, after all, so they’re well aware of geography, and you’ll hear more from them about how Carolina athletics helped shape “Outer Banks.”

We think you’ll probably learn something somewhere in these pages, because we definitely did while putting it together. From Moonlight Graham to the often-discussed but never-located flip scoreboard from Carmichael Auditorium, this issue has a little bit of everything.

And it even has something we’ve never done before—and will never do again.

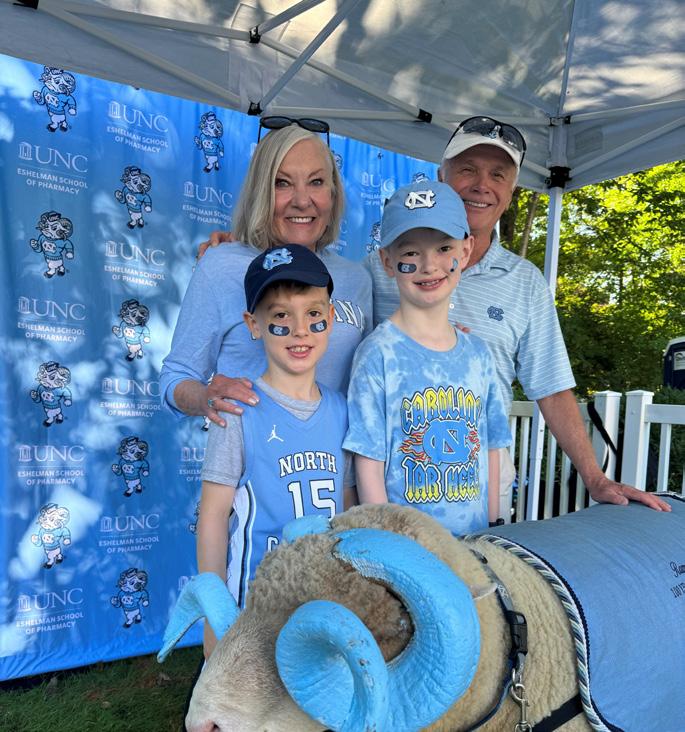

Rams Club staff members know that it’s not a myth that we require member photos in this magazine to fit with the theme of the issue in some way. That regularly frustrates members who just know that their kids/grandkids/friends/ acquaintances are the cutest little Tar Heel around.

So we finally did it. For this edition only, we wanted to break that tradition. And so, for one time only, we’re including as many generic gameday photos of kids and babies in their Tar Heel gear as could possibly fit in these pages.

Not surprisingly, it turns out that many of those members were correct—their Tar Heel kids actually are very cute. And that’s not a myth.

Adam Lucas Editor in Chief

“Back then I thought, ‘Well, there will be other days.’ I didn’t realize that was the only day.” — MOONLIGHT GRAHAM

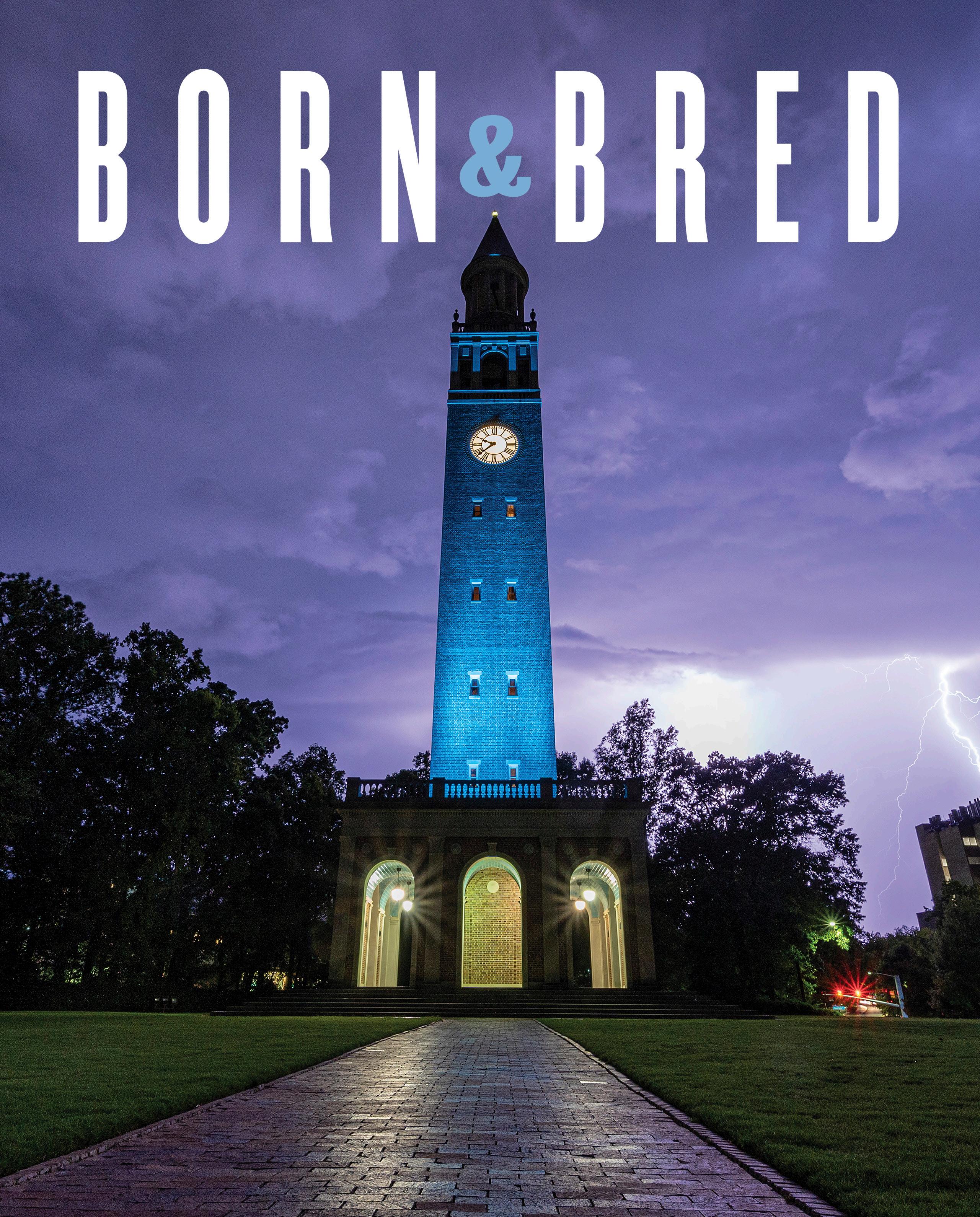

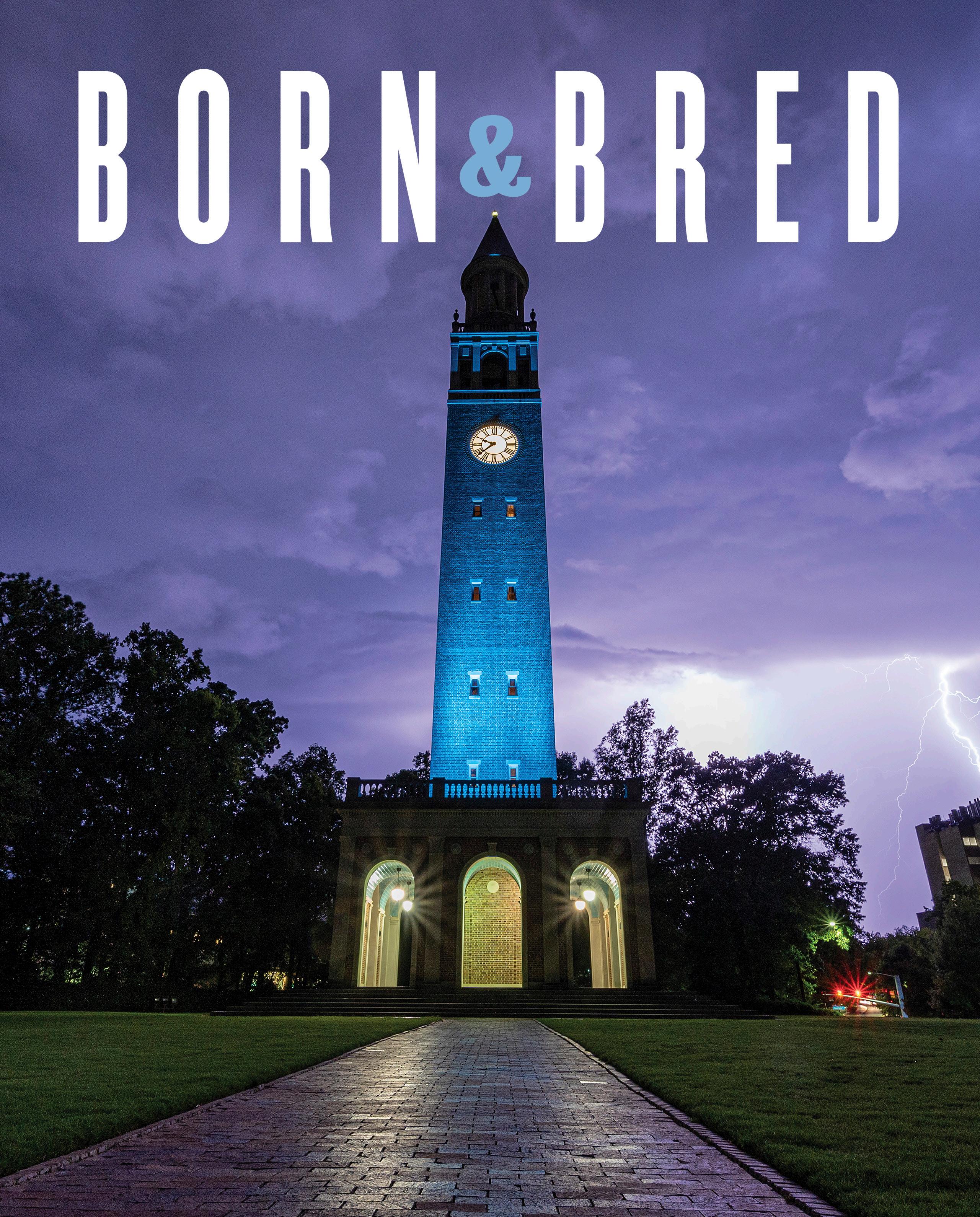

ON THE COVER:

Lighting the Bell Tower blue has become a much-loved— and photogenic—Tar Heel tradition.

COVER PHOTO: GRANT HALVERSON

TOC PHOTOS: JEFFREY CAMARATI, UNC ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS, AND AINSLEY E. FAUTH

MYTH BUSTERS

A Carmichael Auditorium artifact is one of the biggest Tar Heel basketball uncertainties BY ADAM LUCAS

MYTH BUSTERS

Did the Kenan benefactor make a decree about the height of the stadium?

BY LEE PACE

MYTH BUSTERS

Carolina football completely changed the way the game is played BY LEE PACE

EDITOR’S LETTER p. 3

HEEL TICKER p. 6

MYTH BUSTERS

How do you pronounce Boshamer? The answer probably isn’t what you think BY ANDREW

STILWELL

MYTH BUSTERS

The Bell Tower lights blue for some very specific Tar Heel moments BY

LEE PACE

MYTH BUSTERS

Did a legendary golfer once design three holes for Finley Golf Course? BY

LEE PACE

MYTH BUSTERS

The Tar Heels are omnipresent in the media, but some references are factual and others a little more creative BY ADAM LUCAS

TAR HEEL PERSONALITIES

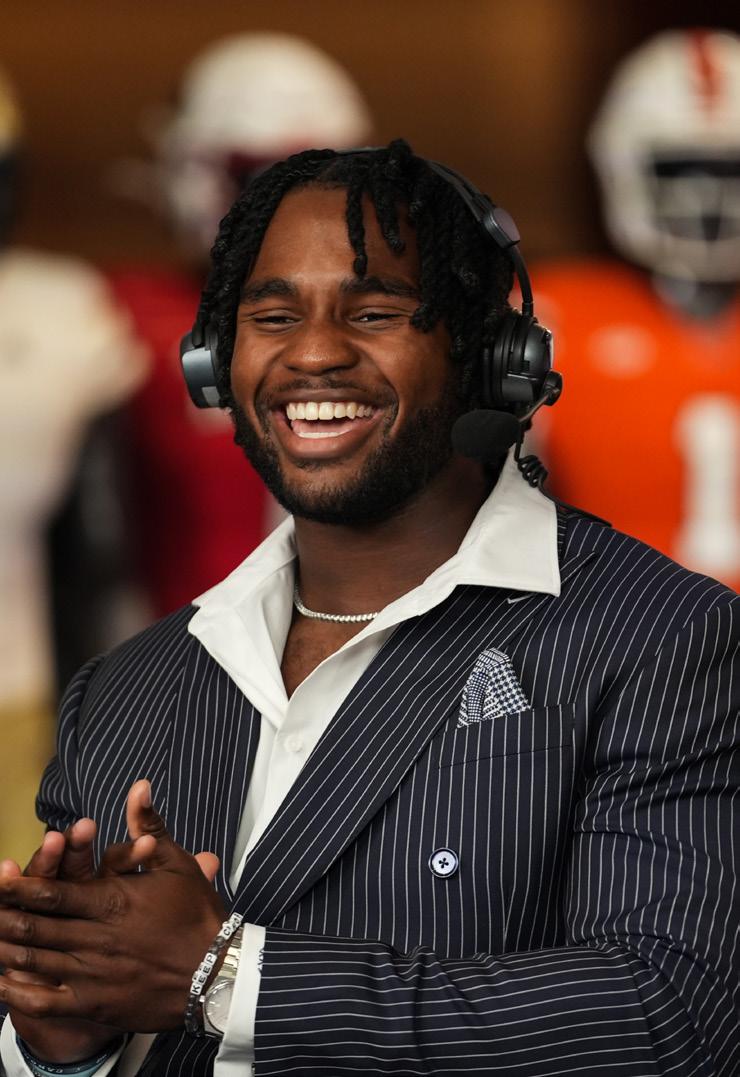

Kaimon Rucker’s success in the modern era of college athletics has enabled him to make an impact on and off the field BY ANDREW STILWELL

38

One of the co-creators of “Outer Banks” learned vital lessons from Tar Heel basketball BY JOSH PATE FIRST PERSON

For this issue only, we asked for your photos of Rams Club member kids and grandkids on Tar Heel gamedays.

A Carmichael Auditorium artifact is one of the biggest Tar Heel basketball uncertainties

BY ADAM LUCAS

Dean Smith would have been a great television executive.

We’re all thankful he followed a higher calling as a basketball coach and beloved University of North Carolina leader, of course. But television—and the viewership habits of decades of fans—would have greatly benefited from following his direction.

The Hall of Fame head coach loved to break down game film. But like so many television viewers of the era, he noticed a problem: while watching the action, it was impossible to keep up with the time remaining and the score.

A temporary fix was for the camera operator to pan up to catch a shot of the arena scoreboard. But that took the focus away from the action on the court, and Smith didn’t want to miss a moment.

So he solved the problem. He spearheaded the creation of a manual scoreboard, operated by two people, that was located in the corner of the Carmichael court nearest the Tar Heel bench and locker room. The scoreboard operators flipped numbered cards to indicate the score, and turned a center card to count down the minutes remaining.

The invention meant the team’s in-house camera could easily capture time and score every time down the court, meaning the Tar Heel coaches always had an easy frame of reference. Like so many

Smith innovations, it’s hard to imagine the basketball world without it. And as usual, he was well ahead of his time—it would be almost 30 years before television broadcasts began including a constant time and score graphic.

Of course, the planning wasn’t perfect. The location of the scoreboard meant it was directly in the way when the Tar Heels needed to run to the locker room at halftime and the end of the game (in the Carmichael era, extended postgame handshakes never happened; the buzzer sounded, the game ended, and the teams left the floor). So with a minute left, the two scoreboard operators collaborated to pack up the board and wheeled it under the bleachers behind the team bench.

Since in addition to being a television innovator, Smith was also a frequent comeback author, the board logistics sometimes created an issue. At the outset of the 1982-83 season, Carolina trailed Tulane late. The board was put away…but then the Heels forced overtime.

“We had put the scoreboard away and then I ran through the concourse to sit with my parents,” says Thad Williamson, who had a family connection with Bill Guthridge through a local church and was therefore drafted to be one of the scoreboard operators. “We had never talked about overtime. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. So I sat there and watched with my parents.”

Just as it was a quintessential part of Smith’s game film viewing, it became a fixture for years of Tar Heel fans who watched the games from Carmichael on television. So it’s natural that those same fans who grew up dreaming of being allowed to flip the Carmichael scoreboard numbers would wonder where that same board might be today.

The answer: no one is sure.

The scoreboard made the move from Carmichael to the Smith Center when the men’s program opened the new facility in January of 1986. From there, though, it seemingly disappeared.

One legend has it that the Atlantic Coast Conference used it for an ACC Tournament display in Greensboro and never returned it. But even a recent league office move from Greensboro to Charlotte didn’t uncover it.

There are some Tar Heel fans who believe they remember seeing it at the Blue Heaven Basketball Museum, a Chapel Hill storefront that predated the current on-campus Carolina Basketball Museum. Blue Heaven was run by former UNC manager David Daly. “That scoreboard has become its own legend,” Daly says. “I tried and tried to find it in the Blue Heaven days…I had heard through the grapevine it might be in a storage building on Finley Golf Course Road.”

But Daly’s investigations came up empty, as has every other inquiry into its whereabouts.

Other artifacts from the men’s basketball era of Carmichael have survived. The center hung scoreboard is on display at the Carolina Basketball Museum. One of the end zone scoreboards is in a private collection. The other is in a slightly unexpected location—Rams Club

THE RAMS CLUB Scan here to login to your Rams Club account and download your membership card to your digital wallet!

member Kathryn Young Galla found it this summer at Paul’s of Oak Island. But even if it’s in an unusual spot, at least it’s preserved. The same can’t be said—at least not with confidence—about the flip scoreboard.

When Carolina hosted Wofford as part of a one-time-only 2019 return to Carmichael, the game naturally couldn’t be played without the return of the flip scoreboard. The Smith Center maintenance crew was commissioned to make a nearly exact replica, and it reclaimed its place of honor near the corner of the Smith Center court.

But the changing television landscape meant the utility of the scoreboard wasn’t still the same. The coaches no longer needed it when reviewing game film. A generation of savvy Tar Heel television viewers didn’t make certain to check it in the corner of the screen on every trip down the court.

And having outlived its usefulness, the board faded from the public eye and eventually faded away completely. Maybe it’s in a basement somewhere. Maybe it’s in an unsearched corner of the Smith Center. Maybe someone has forgotten they have it.

“That scoreboard,” Daly says, “is probably one of the biggest mysteries of Carolina Basketball.”

TBY LEE PACE // PHOTO BY UNC ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS

he beauty and aesthetics of Kenan Stadium in the heart of the Chapel Hill campus are unmatched in college football.

“Kenan Stadium sits in a natural valley, hidden away from mankind,” noted author Frank Deford once wrote. “If you were a stranger, you would not even know that a stadium was there until you came through the woods all around, through the gates, and looked down upon the bowl. There are pines all about it, and some sycamores, poplars, and cedars, as well, and today, just this week, the first color was coming to the sycamores, so there was a crown of fire running around the top of the stadium.”

The popular myth holds that William R. Kenan Jr., the stadium’s benefactor, decreed upon donating the funds for the mid1920s design and construction of the facility that the manmade structure should never rise above the horizon of the surrounding pine trees and forest.

Former Carolina athletic director John Swofford was aware

of that perception and in the early 1980s sought clarification from Frank Kenan, a cousin of William’s and the man sitting at the head of the family table where its involvement with the University was concerned. Swofford planned to build a new press box and add permanent lights going into the 1988 season.

“Frank was a very competitive man by nature,” Swofford says. “He understood change and the need to have some vision in terms of the future and things you needed to do to stay competitive. He said, ‘John, you have a program to run, it needs to be successful, we all want it to be successful. If you need to put lights in that go above the pine trees and put in a new press box, you need to do that. I’ll be one hundred percent supportive.’ He did say this pine tree thing was a myth. That’s the exact word he used. It was probably good mythology, though, but not the truth.”

VERDICT: MYTH!

BY LEE PACE

College football today is a high-octane game of tempo, no huddles, four-wides and quarterbacks who are in the thick of NIL bidding wars. The Tar Heels over the last five years have enjoyed the arm talents of Sam Howell and Drake Maye, who combined threw for more than 10 miles worth of pass completions.

And to think—it all started with an illegal (at the time) forward pass by a Tar Heel player in an 1895 game in Atlanta.

At the time in the late 1800s, football was more akin to rugby in that there was no downfield passing allowed and most plays were massive scrums of humanity in the mosh pit of the line of scrimmage. Broken bones and concussions were rampant and into the early 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt threated to outlaw the game because it was too dangerous.

Against this backdrop, Carolina was set to play Georgia in Atlanta on October 26 as part of a threegame swing through Atlanta, Nashville and Sewanee. They were scheduled to play three games in four days (yet another testament to the game’s physical stress).

“

and allowed the play to stand.

Stephens remembered the play nearly half a century later in a 1940 story in The Asheville Citizen:

“The ball was taken from the center by Joe Whitaker, our quarterback, and given to captain Ed Gregory, who played left end, as he charged through the backfield. As I recall, the play was to go off-tackle. It was permissible in those days to pass the ball behind the line of scrimmage so long as the pass was lateral and not forward.

“WHAT HEISMAN BEGAN TO ENVISION AFTER WITNESSING THIS FLUKE WAS A WAY FORWARD, BOTH LITERALLY AND METAPHORICALLY, A METHOD FOR TURNING FOOTBALL FROM A CRAMPED BATTLE FOR SPACE AND CONTROL INTO A GAME OF BEAUTY AND CHANCE.”

“Well, we had several plays where the ball carrier would pass to a teammate if he was tackled before he got past the scrimmage line, but I don’t recall if this particular play was one of those. Anyway, soon after Gregory received the ball from Whitaker, I remember looking up just as he tossed the ball to me. I was perhaps five yards or more away from him, and I didn’t know that it was a forward pass and not lateral. I merely grabbed the ball and ran through a clear field to a touchdown.”

Five minutes into the game, the Tar Heels executed what was described in newspaper accounts as a “double pass,” with end Edwin Gregory passing the ball to halfback George Stephens, who raced 70 yards for a touchdown. At the time, touchdowns were four points and conversions were two points. That 6-0 lead Carolina took early in the game would stand as the final score.

Georgia coach Pop Warner argued with the referees that the pass was illegal, but none admitted to having seen it properly

Watching from the sideline that day was John Heisman, the coach at Auburn who was scouting Georgia for a future game with the Bulldogs. A light went off in Heisman’s mind. Such a play with the ball traveling by air outside the scrum of the line of scrimmage would open the game up and eliminate some of the injuries borne of a violent game played in tightly packed confines.

“What Heisman began to envision after witnessing this fluke was a way forward, both literally and metaphorically, a method for turning football from a cramped battle for space and control into a game of beauty and chance,” wrote Michael Weinreb in

The Athletic in a 2019 series celebrating the 150th anniversary of college football. “What Heisman began to imagine was a way for football to achieve balance, an aerial lifeline for a sport that was increasingly hidebound and landlocked and in danger of giving way to its basest instincts.”

Heisman immediately took the idea to Walter Camp, the well-established coach deemed in many circles “The Father of Football.” Camp was a former Yale coach who lost only two games over five seasons in New Haven and now was the coach at Stanford and the head of the football rules committee. Heisman was twenty-six years old and had a more progressive view of football than did Camp, ten years his elder.

Heisman’s idea fell on deaf ears, unfortunately. Camp believed the pass would allow luck to play too big a role in the game and lead to flukish plays. He thought the violence was essential to the sport’s character, and one of his sympathetic committee members referred to “lightweights” in the discussion of how passing and catching would change the game. Camp thought the pass would

make, in essence, for a softer type of football.

It took 10 more years and the mandate of President Roosevelt in 1905 to force the powers-that-be into allowing the legalization of the forward pass. Beyond the safety measures, Heisman looked into the future and the appeal that the forward pass would bring to football.

“It is certain the spectators will greatly prefer to watch the open game,” he said. “They like to see nimble hurrying and scurrying, fleet running hither and thither; they like to see the ball itself now and then, they like to see it kicked high in the air back and forth. Often, they like to see a runner gain his distance by fleetness and dodging, a team by strategy or boldness of plan.”

And thus the dominoes began falling toward the game that in the last decade has allowed Tar Heel QBs Marquise Williams, Mitch Trubisky, Sam Howell, Drake Maye and Jacolby Criswell to have single-game passing marks of 448 yards or more.

Behind 850+ Carolina student-athletes are supporters who are establishing their legacy with Carolina Athletics through long-term philanthropic planning with The Rams Club. Planned gifts combine your philanthropic goals with smart financial strategies.

To learn more about simple, meaningful and tax-wise giving opportunities, contact Beth MacKethan at 919-843-6448 or beth@ramsclub.com

How do you pronounce Boshamer? The answer probably isn’t what you think.

BY ANDREW STILWELL PHOTOS BY AINSLEY E. FAUTH

Even if you’re one of the most casual of Carolina baseball fans, you know that since the early 1970s, the Tar Heels have played their home games at Boshamer Stadium, one of the Top 20 largest NCAA Division I baseball venues by seating capacity in the country.

As you’re reading this, you’ve probably heard the voice inside your head pronounce “Boshamer” like many fans recognize it today – “Bosh-a-mer.” Whether you’ve attended a game in person, listened on the radio, or watched on television, this is a pronunciation that you’ve heard dozens of times.

However, in a recent interview on the Carolina Insider podcast, former head coach Mike Fox presented an alternate pronunciation for the iconic home of the Diamond Heels.

“You told me there would be no hard questions before I came in here,” laughed the longtime skipper for the Tar Heels, who won 948 games between 1999 and his retirement in 2020. “I’ve always called it Cary C. Bosh-hammer Stadium. Have I been wrong all these years?”

“That’s the name - Bosh-hammer – that’s the name I’ve always heard since I’ve arrived here,” Fox said. “That’s even dating back to my days as a student.” (Fox played second base for the Tar Heels from 1976-1978.)

Which leads us to wonder…Bosh-a-mer, Bosh-hammer, or some other way…how should Boshamer really be pronounced?

HAVE WE ALL BEEN SAYING “BOSHAMER” INCORRECTLY?

For six decades, Carolina Baseball played their home games on Emerson Field, the University’s main athletic field that dated to 1916. Home to Carolina’s football and track teams – who moved to Kenan Stadium in 1927 and Fetzer Field in 1935, respectively – Emerson Field was razed in 1967 to make way for Davis Library and the Graham Student Union.

The baseball team needed a new “home field,” and would move a short distance down Country Club Drive, to a baseball diamond located adjacent to Avery Dorm. Originally announced in March of 1970, Boshamer Stadium would be built around the existing diamond and was made possible by a gift from Gastonia textile industrialist Cary C. Boshamer, who graduated from Carolina in 1917.

Boshamer, who played football for the Tar Heels during his time as a student and was later a member of the University of North Carolina system Board of Trustees, was described by past Carolina Chancellor Lyle Sitterson as a “loyal friend” to the University.

“Mr. Boshamer is one of the most loyal friends of the University,” Sitterson was quoted in a March 1970 Daily Tar Heel article. “His generosity extends to all areas of the University. The Boshamer professorship and Boshamer scholarship along with his other contributions are making possible significant advancements at the University. We are deeply grateful for him.”

“This gift is another example of Mr. Boshamer’s tremendous interest in and loyalty to the University,” added then baseball coach Walter Rabb. “It is something in which all Carolina baseball people will take pride. We are deeply grateful for his wonderful generosity to the athletic program and to the University.”

“

Ryan Lynch – a sentiment that was echoed by his battery mate, freshman catcher Mitch Wilson.

The same holds true for Carolina Baseball radio play-by-play voice Dave Nathan, who has been calling games for the Diamond Heels since 2013.

“The way that I’ve always said it is ‘Bosh-a-mer,’ Nathan said. “That’s the way I’ve always heard it. I know there are stories out there where the family has preferred the ‘Boss-hammer’ pronunciation, and I recall from doing shows with Coach Fox that he always put a little extra pronunciation on ‘Bosh-hammer’ but most of the people I’ve heard say it is the way I say it, which is ‘Bosh-a-mer.’”

“It’s funny though, with every game that we do on the radio, we have a pronunciation guide for the players’ names on both teams,” he continued. “Maybe we need to add Boshamer Stadium to that list going forward.”

There is a slight deviation, depending on who you ask, however. An example: freshman shortstop Boaz Harper actually leans more towards Coach Fox’s long time “Bosh-hammer” pronunciation.

While the name is known primarily in baseball circles at Carolina, the Boshamer family name also has a strong non-athletic significance at the University.

“IT’S FUNNY THOUGH, WITH EVERY GAME THAT WE DO ON THE RADIO, WE HAVE A PRONUNCIATION GUIDE FOR THE PLAYERS’ NAMES ON BOTH TEAMS. MAYBE WE NEED TO ADD BOSHAMER STADIUM TO THAT LIST GOING FORWARD.”

Carolina began play in the stadium during the summer of 1971, and Boshamer Stadium was officially dedicated on April 8, 1972 – a doubleheader where the Diamond Heels were no-hit by Maryland in the first game. In fact, a broken bat from that game that was presented to Mr. Boshamer mid-game resides in the Carolina Baseball Museum to this day.

Unfortunately, Boshamer would pass away the next year, in June of 1973. But his legacy at Carolina continues to live on in many ways across the University.

Through the years, the most-common pronunciation of Boshamer has proven to be the phonetic “Bosh-a-mer” version. Fans, television broadcasters, and even members of the baseball program typically refer to Carolina Baseball’s home field in this way.

“I pronounce it Bosh-a-mer Stadium,” said incoming freshman pitcher

In addition to his athletic support, Boshamer also endowed a distinguished professorship at Carolina beginning in 1969, which are among the highest campus-wide recognitions of excellence. While there are not specific selection criteria, there are currently six professors at Carolina who have earned the honor of Boshamer distinguished professorship, representing a wide array of academic departments.

As is the case in athletics, the “Bosh-a-mer” pronunciation is common amongst the academicians as well.

“I’ve always heard it pronounced “Bosh-a-mer,” said Thomas L. Hazen, Cary C. Boshamer Distinguished Professor of Law, who joined the Carolina faculty in 1980 before obtaining the Distinguished Professorship title in 1991.

Dean of The Graduate School and Boshamer Distinguished Professor of Nutrition and Medicine Beth Mayer-Davis took a bit more of a noncommittal approach to the pronunciation debate.

“I actually received an email and then phone call from an alumnus maybe a year or two ago – specifically for the correct pronunciation. I’m pretty sure the fellow knew what he was talking about!” She said. “We need to get this right – we could unintentionally offend some folks here!”

While the “Bosh-a-mer” pronunciation is common throughout the University of North Carolina, a more definitive answer might be found

from someone close to the family.

Boshamer and his wife Kathleen, who passed in 1979, did not have children of their own. He was succeeded in his textile businesses by two nephews, Wilson and Henry, who have also since passed away. However, that doesn’t mean that the “official” Boshamer pronunciation is lost to time.

In a May 2010 issue of the Gaston Gazette, a former neighbor of the Boshamers, Mike Sumner, was profiled by the paper for donating the aforementioned broken bat from the 1972 dedication game to the newlyopened-at-the-time Carolina Baseball Museum.

“I had gone with Mr. Boshamer to the stadium dedication game against Maryland,” Sumner told the paper in 2010. “And the second batter for North Carolina broke his bat and (UNC) coach (Walter) Rabb came over and gave it to Mr. Boshamer. Mr. Boshamer later gave the bat to me, and I’ve kept it ever since.”

Sumner was a pseudo-grandson to the Boshamers and would regularly accompany “Mr. Boshamer” to countless Carolina sporting events in the 1960s and 1970s. More than 50 years after their friendship formed, he is adamant about the one true pronunciation of “Boshamer.”

“It’s Boss-hammer,” Sumner said. “His family is from Salzburg, Austria, and it is pronounced Bosh-hammer over in Austria, but he was very adamant about Boss-hammer. I heard him correct many people that tried to call him Bosh-a-mer or Bosh-hammer, but it was Boss-Hammer.”

“I asked him once, and he said, ‘Well, it’s a German name, but we’re in America now.’” Sumner said. “I met the rest of his family when I was in college. I went over to see them, and they go by Bosh-hammer, but Mr. Boshamer, he was adamant about it. I think from my 13th to 14th birthday to when he died, when I was maybe 18 or 19, it wasn’t a week would go by where he wouldn’t correct somebody on that.”

(Author’s Note: There is also a note in the Wikipedia page for Boshamer Stadium that the family preferred the “Boss-hammer” pronunciation, citing a now-dead link to an article from Charlotte’s WBTV.)

“THE BOSS”

With the (perhaps) de facto answer coming from a longtime family friend, is it time to start putting the correct emphasis on the Diamond Heels’ home? Sumner thinks so.

“To me, I don’t think people should call it Bosh-a-mer Stadium, because that’s not how Mr. Boshamer pronounced his name,” he said. “I know people call it ‘The Bosh,’ but if you’re looking for a new nickname, you can call it ‘The Boss.”

“To me, that’s better than ‘The Bosh,’ anyway! What even is a ‘Bosh’?”

Change is a constant in college athletics these days – with new challenges and opportunities emerging almost daily. There is one constant, however, in this shifting landscape: Carolina Athletics and The Rams Club’s commitment to excellence.

Athletic program needs evolve. It is essential for Carolina to develop flexible strategies to provide critical resources for all 28 of our sports and to maintain our high standard of excellence for a broad-based program. To achieve this, The Rams Club is launching two new funds designed to provide adaptable, sustainable support for Carolina Athletics and our Tar Heel student-athletes – the Carolina Athletics Excellence Endowment and the Carolina Athletics Excellence Fund.

The Carolina Athletics Excellence Endowment will provide a long-term funding solution with critical, built-in flexibility to adapt to future needs. This endowment will produce an annual yield that will be used in two primary ways: first, the funds provided from this endowment will address our commitment to scholarships – covering any scholarship deficit beyond what the Scholarship Endowment Trust provides; second, the funds will be truly flexible to meet the variety of funding challenges and opportunities Carolina Athletics will face in the years to come.

The Carolina Athletics Excellence Endowment will provide a long-term funding solution with critical, built-in flexibility to adapt to future needs. This endowment will produce an annual yield that will be used in two primary ways: first, the funds provided from this endowment will address our commitment to scholarships – covering any scholarship deficit beyond what the Scholarship Endowment Trust provides; second, the funds will be truly flexible to meet the variety of funding challenges and opportunities Carolina Athletics will face in the years to come.

The Carolina Athletics Excellence Fund also seeks to provide flexible, unrestricted funding by making resources immediately available to address today’s needs. A robust Excellence Fund enables Carolina to respond swiftly to current challenges as well as seize emerging opportunities.

The Carolina Athletics Excellence Fund also seeks to provide flexible, unrestricted funding by by making resources immediately available to address today’s needs. A robust Excellence Fund enables Carolina to respond swiftly to current challenges as well as seize emerging opportunities.

Rams Club members believe in our mission – to provide educational and athletic opportunities to Carolina student-athletes. With the establishment of the Excellence Endowment and the Excellence Fund, donors can provide Carolina Athletics with the agility and flexibility to remain championship-focused in an incredibly dynamic environment. We invite you to consider supporting these new initiatives.

These adaptable funding initiatives will allow Carolina to provide:

Scholarship & Access: The first priority of the Excellence Endowment and Excellence Fund is to supplement the cost of scholarships for student-athletes not covered by the Scholarship Endowment Trust.

Unrestricted Financial Support: Once the priority of scholarships is met, the fund will provide unrestricted support to:

Unrestricted Financial Support: Once the priority of scholarships is met, the fund will provide unrestricted support to:

Meet Changing Needs by providing the resources necessary to adapt to new opportunities in the evolving college sports landscape.

Enhance the Student-Athlete Experience through investing in development initiatives, like support services, academic programs, and mental health resources.

Support Coaches & Staff by providing the financial flexibility to invest in coaching talent, leadership development, and staff training.

Provide Elite Facilities with cutting edge tools and environments to advance our teams as sports science and technology grow, optimizing development and performance.

Important details about the Excellence Endowment and Excellence Fund and your Rams Club membership: In recognition of the importance of flexible, supplemental support of Carolina Athletics, gifts to these funds can earn valuable bonus Priority Points. Gifts to the Excellence Fund will earn 2 points per $100 donated (other gifts earn 1.0 point per $100 donated). Gifts to the Excellence Endowment will earn 1.4 points per $100 donated.

Similar to the Scholarship Endowment Trust, qualifying gifts to the Excellence Endowment will secure rights to Men’s Basketball season tickets. For more information, please visit ramsclub.com/excellence. Participation in these funds is supplemental to your annual Rams Club membership. Gifts to these initiatives do not replace or satisfy annual membership obligations or provide benefits of membership.

With your help, Carolina can continue to exemplify excellence in an uncertain landscape, providing our student-athletes with the best experience in college athletics. You can ensure that our student-athletes and programs remain competitive, adaptable, and well-supported in this new era of collegiate sports. For more information, please visit ramsclub.com/excellence or scan the QR code here.

L I G H T I T

IS THE BELL TOWER ONLY LIT BLUE FOR FOOTBALL WINS?

BY LEE PACE

Under the lights. Prime time TV. Full house. The first game of Mack Brown 2.0. And a pulsating 28-25 win for the Tar Heels over Miami.

The Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower was bathed in Carolina blue light late that evening of Sept. 7, 2019.

“Enjoy this new view of Carolina’s Bell Tower following football victories this fall. Go Heels,” Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz tweeted with a photo of the 172-foot red brick tower that opened in 1931.

N.C. State fans howled that the Tar Heels were copying a practice established in 1998 of its Memorial Tower being illuminated in red following significant athletic accomplishments.

“Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” said one State fan on social media.

“If you can’t beat them, copy them?” added another in reference to a three-year Wolfpack win streak over the Tar Heels in football.

In truth, the idea in Chapel Hill actually was generated during the Mack 1.0 era. Brown, who coached the Tar Heels from 1988-97 before moving to Texas for a 16-year-run, had the idea in the mid-1990s. He took it from a long-standing tradition at Texas, where the UT Tower has been lit in burnt orange to celebrate athletic and academic achievements since 1937.

He was working on making it happen before he got the Texas job.

It became a priority to make happen when he returned in 2019.

At first, UNC athletic officials arranged to have a local production company use temporary lights following football wins. Then when new LED lights were installed in the stadium prior to the 2023 season, four

permanent lights were installed that are turned on with the flip of a switch. Technological improvements also mean that after home wins, the player judged to have the biggest impact in that victory flips the switch that lights the tower. Since the upgrades, that ceremony takes place on the field immediately after a win.

The lighting also extends off the athletic playing fields—Carolina also has a new tradition of illuminating the Bell Tower in blue and white on the eve of the first day of classes to celebrate the start of the school year.

There are four very specific occasions when the Bell Tower is lit blue. 1 2 3 4

After a Carolina football victory

After a Tar Heel national championship in any Division I sport

The eve of the first day of classes of a new school year

Commencement weekend

VERDICT: MYTH!

BY LEE PACE // PHOTO BY MONTY AERIALS

“Nicklaus Holes” at Finley Golf Course. Let’s tee that myth up and knock it to smithereens.

In the early 1980s, the athletic department needed room to build lacrosse, soccer and two softball fields and identified three holes on flat ground at Finley Golf Course that could be converted. That required building three new ones.

At the time, the front nine began with three holes on the west side of Finley Golf Course Road, the par-4 holes running behind the row of fraternity houses that fronted the road. The holes stretched north toward the back of the old University Inn and made a counterclockwise turn to run through the woods and eventually return back to the clubhouse. The fifth, six and seventh holes were removed for the new fields.

The athletic department owned land that surrounded the golf course and the Highland Woods Road neighborhood that was just to the east of Highway 54 Business (Fordham Boulevard today). It offered that ground to a golf course architect to find and design three new holes.

Jack Nicklaus II was on the Tar Heel golf team from 1980-83 and

his dad, at the height of his professional career and also established as a major force in the golf course design world, made several visits to Chapel Hill for exhibitions, basketball games and fund-raising events. Everyone seemed to believe that Nicklaus designed and built the new holes.

Au contraire.

The original course architect, George Cobb of Greenville, S.C., built the new holes that opened in 1982. The nines were reversed at the time and the new holes became the 14-16.

“Jack looked at the property but said he would never touch a golf course if the original architect were still alive,” says Ed Ibarguen, who was on the Finley golf staff at the time. “But the rumor persisted and, honestly, the people in charge at the time did nothing to dispel it because it was good for recruiting and the reputation of the golf course.”

Those holes were abandoned during the 1999 Tom Fazio course rebuild. That 16th hole sits on ground now occupied by the Ronald McDonald House and SECU House.

Rams Club members like to wear their Carolina Blue, and they’ll wear it all over the US and the world. If you have a photo of you in your Carolina gear in front of notable landmarks in the US and abroad, send them our way to be a part of Carolina EveryWear! C V E L W R R A E O Y 1 2 3 4 5

N A I E A R

To have your photo included:

-Send your photo digitally to bornandbred@ramsclub.com.

-Identify everyone in your photo and the location of the photo.

Here are the “Rules”:

-At least one person in the photo has to be a Rams Club member

-You must be wearing Carolina gear

-You must be in front of a notable landmark (sorry, as cool as Kenan Stadium and the Smith Center are, they don’t qualify).

1) Tim & Debbie Burgiss of Statesville, NC, on top of Mount Pilatus in Lucerne, Switzerland; 2) Chancy & Keith Kapp of Raleigh at the San Miguel Chapel in Santa Fe, NM; 3) Harper Donahoe & Kathy Burant of Natural Bridge Station, VA, at Mount Rushmore; 4) Jason, Shana, M & L Lentz of Springfield, OH, at Mormon Row, Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming; 5) Marvin Carver & Barrett Carver of Durham at Disneyland in Paris; 6) Ben, Martha, Chesley & Brinkley Lucas & Chris Walters of Sanford, NC, at Cayman Brac; 7) Sara, Scott & Luke Laws of Arden, NC, at the Montserrat mountain outside Barcelona, Spain; 8) Laura & Ava Allred of Kernersville, NC, in front of Midnights Clock in Liverpool, England; 9) Holly Fishback of Durham at the Ward Charcoal Ovens in Ely, Nevada; 10) Dennis & Amy Goss of Chapel Hill at the Cliffs of Moher, Ireland; 11) Liz Crowley & James Crowley Guerrero of Troutman at Miami Beach; 12) Olivia Croom of Wilson, NC, at the Cliffs of Moher, Ireland; 13) Steve Erwine of Apex, NC, at the ESPN Gameday before the FSU/GT game in Dublin, Ireland; 14) Scott Hummel & Cindy McCauley of Greensboro, NC, at the Tour de France finale in Nice, France; 15) Randy & Nancy Tapp of Cheshire, CT, at the Colosseum in Rome; 16) Dee & Ed Lowdermilk of Chapel Hill at the Skogafoss Waterfall in Iceland; 17) Hayden, Caroline & Jason Hux of Savannah, GA, at Innishmore Island, Ireland; 18) Doug & Mary Weaver of Durham at the Devil’s Tower in Wyoming; 19) Rufus & Toni Langley of Apex, NC, at the VanDusen Botanical Gardens in Vancouver, BC; 20) Joe Jauch & Gracie Jauch of Forest, VA, at Glacier National Park in Montana; 21) Fred & Lisa West Womble of Elizabeth City, NC, in Jungfraujoch, Switzerland; 22) Beth Harris Isenhour of Chapel Hill at Dunvegan Castle in Isle of Skye, Scotland; 23) Brenda & Sam Tie of Raleigh at the Blue Lagoon in Iceland; 24) Fred Eidson & Barbara Haynes of Elkin, NC, and Steve & Ann Yokeley of Mount Airy, NC, at Puerto de la Cruz on Tenerife, Canary Islands; 25) Michelle Cunningham of Glen Rock, NJ, at White Rocks Beach in Kefalonia, Greece; 26) Jan & David Rockwell of Wilmington, NC, in Barcelona, Spain; 27) Susan Bowman of Oxford, NC, in Wiesbaden, Germany; 28) Bennett, Dave & Jada Simpson of Elizabeth City, NC, at Kirkjufellsfossar, Iceland 16 19 17 20 18 21 22 28 25 24 27 26

SHOW US YOUR COLORS! 23

The Tar Heels are omnipresent in the media, but some references are factual and others a little more creative

BY ADAM LUCAS // PHOTOS

“You can’t let geography get in the way of a good story.”

Let’s clear this one up at the very beginning: Josh Pate and Shannon Burke, the two Carolina graduate creators of the hit Netflix show “Outer Banks,” are well aware that you can’t take the ferry from the Outer Banks to Chapel Hill.

But in the first season, characters in the show do exactly that. And somehow, despite the fact that the show is very clearly fictional, that one detail has become one of the most frequent nitpicks.

The reason for the ferry? Blame the editing room. “In the scene

in front of the library, you see them getting out of a car,” Burke says. “It’s in the script and we filmed an entire scene with the characters in the Uber.”

“We ended up killing it,” Pate says. “You can’t let geography get in the way of a good story.”

And the slight quibble didn’t impact the popularity of “Outer Banks.” Over 15 million people streamed the fourth season of the show when it was released in October, immediately shooting it to the top of Netflix’s viewership rankings.

Both Burke and Pate are enormous Tar Heel basketball fans. In fact, Pate credits the 2017 national championship team with serving as the spark for the genesis of “Outer Banks.” His fandom also sparked a unique cameo, as Armando Bacot made a guest appearance on the third season of the show. He didn’t have to stretch very far, as he played a character named Mando.

Read more from Pate in this edition’s back page column (Page 38).

“It sounds like he had a great story, but he wasn’t the basis for my story.”

Charlie Justice’s life story certainly could have been a movie.

Better known as Choo Choo, the Asheville native remains one of Carolina’s all-time greats even three-quarters of a century after he last played for the Tar Heels. The 22-yard line at Kenan Stadium is painted blue in his honor, and a statue of him stands outside of Kenan.

Justice’s multiple talents on the football field earned him Heisman Trophy runner-up status in 1948 and 1949, and he helped Carolina participate in two Sugar Bowls and a Cotton Bowl.

Like so many young men from his generation, Justice attended Carolina only after serving in World War II, utilizing the GI Bill as his ticket to higher education. He was truly great in everything he did—as a football player, in the classroom, and as a husband to his wife of 59 years, Sarah.

It’s a story that seems written for the movies. And it was…or maybe it wasn’t.

Legendary Sports Illustrated writer Frank Deford released the book Everybody’s All-American in 1981. In 1988, it was made into a movie starring Dennis Quaid and Jessica Lange.

In the book, the protagonist—Gavin Grey—attends Carolina before being drafted by the Washington Redskins. Those details mirror Justice’s career.

But when the film was searching for a setting, University officials turned down a request to film in Chapel Hill. The book has a much darker ending than the movie, and they didn’t want to be associated with anything that might besmirch Justice’s legacy. Filming was eventually moved to LSU.

Because of the obvious parallels—Carolina to Washington for a post-World War II star football player—there has long been speculation that Deford’s story was based on Justice.

But while researching a book on the 1957 Carolina championship team, I visited with Deford in his apartment in New York City. That day, when he asked if I had any further questions, I asked him whether “Everybody’s All-American” was indeed based on Justice.

Deford was just as you might imagine—taller than you would expect and nattily dressed, including an ascot. He peered at me over his glasses and delivered, as far as I’m concerned, the final word on this topic:

“I never met Charlie Justice,” he said. “It sounds like he had a great story, but he wasn’t the basis for my story.”

“The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball.”

“Field of Dreams” is one of the best sports movies in the history of American cinema. It also has a subtle Carolina connection.

One of the secondary characters is Archibald “Moonlight” Graham.

One of protagonist Ray Kinsella’s many quests is locating Graham, who in 1922 played one inning of a major league game in the field and never received an atbat. Graham went on to become a

doctor, but in the movie he tells Kinsella that he still dreams of that one inning as a major leaguer.

In the movie, Graham lives in Minnesota, and the doctor did indeed become a beloved town physician in Chisholm, Minn. But the film doesn’t cover the origin of his medical roots.

The real Moonlight Graham—who was the older brother of eventual UNC system president Frank Porter Graham—was born in Fayetteville and raised in Charlotte. He graduated from Carolina in 1901 and earned a certificate of medicine in 1902, and is included in the baseball team photo in 1900.

Graham’s real life is Hollywood enough that it was the subject of a 2009 book, “Chasing Moonlight” by Brett Friedlander.

“You’re Michael Jordan, and your story is going to make us want to fly.”

Michael Jordan’s storied career has been the subject of numerous books, movies and the Covid sensation “The Last Dance” documentary.

One of the most recent additions to that pantheon was the 2023 movie “Air.” The film traces the origin of Jordan’s relationship with Nike. As the shoe company begins to woo the Tar Heel standout, two Nike executives meet to review the footage of Jordan sinking the championship winning jumper against Georgetown in the 1982 NCAA finals.

That three-minute scene features multiple Tar Heel hoops references—most of which are even true.

Claim 1: Lynwood Robinson was more highly rated than Jordan coming out of high school.

Verdict: It’s true that Robinson (and Buzz Peterson) probably had a longer reputation in basketball recruiting circles than Jordan. But Jordan was rising quickly among national scouts and had long been a primary Tar Heel target. Robinson, meanwhile,

suffered a knee injury during his senior year of high school that limited his effectiveness.

Claim 2: “The play is drawn up for Jordan.”

The entire premise of the scene is based around the idea that with Carolina trailing by one point in the championship game’s final seconds, Dean Smith eschewed getting the ball to future top NBA draft choice James Worthy and instead designed a set for Jordan. “The play is drawn up for Jordan,” the executives say.

Verdict: Well…yes. But as usual, Smith had a backup plan, and his decision to get the ball to Jordan had as much to do with his knowledge of the opposing bench as with any prediction of future stardom.

Smith and Georgetown head coach John Thompson were close friends.

“John Thompson was a Worthy fan,” Smith told SLAM Magazine. “So I knew he would have three guys on James. So he was a decoy.”

As Smith famously told Jordan when the team left the huddle before the final possession: “Knock it in, Michael.” But if Jordan had failed to knock it in, there was a backup plan.

“If he would have missed, Sam (Perkins) would have been on the other side to grab the rebound,” Smith said.

Claim 3: Dean Smith couldn’t win the big one.

Verdict: In March of 1982, this actually was the belief in some national basketball circles. As Matt Damon correctly points out, Smith had led the Tar Heels to three previous title games and

lost all three. Left unsaid is the fact that 1982 was Smith’s seventh Final Four. After losing a bizarre 1981 title game that was delayed by a presidential assassination attempt, Smith took considerable national criticism. The 1982 team, in fact, held a players-only pretournament meeting in which the primary theme was winning a national title for their head coach.

Overall, then, the movie largely gets Jordan’s Carolina story correct. His is one of the utmost rarities: a story so improbable Hollywood didn’t even need to exaggerate it.

KAIMON

HAS ENABLED

BY ANDREW STILWELL // PHOTOS BY UNC ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS & ANTHONY SORBELLINI

In just a few short years, the concept of “Name, Image and Likeness” (NIL) has gone from relatively unheard-of in college athletics to the forefront of many conversations surrounding student-athletes.

“There are a few truths when it comes to name, image, and likeness,” said Kevin Rice, Executive Director of Old Well Management and NC Hall Of Fame (NCHOF), Carolina’s NIL Collective. ”Mainly, it’s not going anywhere, and in some form or fashion, compensation for student-athletes is going to continue. Schools and organizations have two options – they can do it the right way, or they can do it in a way that doesn’t truly benefit the student-athletes. Fortunately, Carolina has done what Carolina always does and have decided to do it the right way.”

Working with nearly 200 student-athletes on more than half of UNC’s athletic teams, NCHOF is a 501(c)(3) non-profit established in 2023 to support and honor University of North Carolina student-athletes of the past, present, and future.

While many fans might see the phrase “Collective” and immediately tense up, Carolina studentathletes, by working with the NCHOF, are actually making the Chapel Hill community a better place through partnerships with area charitable organizations and causes that are important to them.

“You see negative stories about paying players all the time,” Rice said. “In reality, a majority of the time the money is used for positive things, whether it’s a student-athlete helping their family or doing something within their community to help better that community in a way that the student-athletes wouldn’t have previously been able to do.”

“We try to connect these student-athletes and the resources that they now have available to them that they wouldn’t have had before, including community projects that they’re passionate about because they’re all passionate about something,” he continued. “They all have unique life experiences and different things that make them want to support their community and want to get involved.”

One of those student-athletes is Carolina Football’s Kaimon Rucker, who has made a point of utilizing the resources at his disposal to provide a helping hand in his hometown and beyond. While his “on the field” successes over the past several seasons have been plentiful, the graduate student from Hartwell, Ga., is just as proud of his impact off the gridiron.

A stalwart of the Tar Heel defensive line, Rucker is in the unique position of having begun his career as a student-athlete in the “pre-NIL” era. When the idea that compensation for studentathletes’ name, image and likeness might become a reality (along with the potential future

reimagining of a college football video game), Rucker knew he wanted to utilize any financial gain to fully maximize his impact during his time at Carolina.

“At the time it was first being discussed, I was 17 going on 18, so the first thing I thought about was the college football video game that was last released in 2014. You had the players’ numbers, but no names. When it finally happened, I was obviously excited that student-athletes could be paid, but I would finally be able to be in the video game if and when it came back.”

“It’s just like getting that little bit of extra money for doing chores when you were a kid,” Rucker laughed. “I felt like it was something that I could really optimize during my time in Chapel Hill.”

While the concept of name, image, and likeness is still somewhat new, according to Rucker, it’s often misconstrued from the outside.

“A lot of people see the superficial part of it and the bad side. I feel like it’s something that’s often not brought in good light, and there’s just like a lot of miscommunication,” he said. “I feel like there’s a misconception when it comes to that kind of stuff, because you only see the cars or the new chains, you see all this stuff, but it’s just like that’s not the grand aspect of what we’re able to do with these resources.”

Wanting to make an impact off the playing field as much the impact he makes on it, Rucker created a program at his former primary school in northern Georgia where he sends backpacks and hygiene products to those in need. The idea was a brainchild of Rucker and his mother, Kristie, who is a district nurse at Rucker’s elementary alma mater, Hartwell Elementary.

“For me, there was a time in elementary school when I remember learning about hygiene,” Rucker said. “These are 5th grade boys that are growing up to be young men. Around the time in 5th grade, you go through a lot of changes. You go through a lot of hormonal changes, you go through a lot of changes in your body with voice deepening, more hair, body odor, you get the gist. I wanted to let them know and put it in their minds that when they get out of gym class, they sweat and put on [body spray] and keep it pushing. That’s not how it goes! You can still be a man and take care of your body. There’s nothing wrong with using deodorant or scented lotion or putting on cologne.”

“This is like the ground zero, base-level type stuff that you’re going to need from when your body starts changing because it’s just like you can’t control it,” he continued. “It’s a part of life. What you can control is how much care you can take. You’ve got to treat your body like a temple, man. If you don’t take care of the temple, it’s going to crash.”

Dozens of students at Rucker’s former elementary school have been recipients of these care packages – which were all paid for exclusively out of Rucker’s pocket. For Rucker, it’s about using his platform to inspire the next generation. He realizes that he’s not that far removed from being in their shoes.

“Of course, I had my parents, I’ve had family members, I had friends that helped me out with growing up along the way and to develop into the young man that I’m today,” Rucker said. “The idea of having that somebody that grew up the way that you grew up, the same school you went to, that grew up around the same things that you’re doing and the student-athletes that are in that room, I’m the person that they’re trying to be.”

The influence continued beyond his hometown when Rucker recently donated $10,000 to Hurricane Helene relief, an amount that was matched by athletics corporate partners Wells Fargo and Food Lion.

“For me, it was heartbreaking to see towns and places that people cherished so much now suffering,” Rucker said. “And I thought to myself, why not use my platform from the NIL I earn here to give back to the people who truly need it?”

Wells Fargo is committing a matching donation of $10,000 and Food Lion Feeds will donate 10,000 meals that will also be given to the MANNA FoodBank in Rucker’s name.

“My thoughts and prayers are with not only the people of Western North Carolina, but also the entire towns that have been affected by Hurricane Helene,” Rucker continued. “This is just a small drop in a big pond of support for everyone, but we are praying for you and we are still supporting you as you build back from what the hurricane took from all of you.”

Rucker’s presence on the football field was recognized in the pre-season when he was named to the watch-list for both the Bednarik and Nagurski trophies, given to the nation’s top defenders. However, it’s the Witten Collegiate Man of the Year award, given for leadership, both on and off the field, that would mean the most to “Ruck the Butcher.”

“Even before I started getting offers in high school, I told my parents that I wanted to make an impact to whatever institution that I attended. Whether that was athletically, academically, in the community, it didn’t matter. I wanted to leave a mark at the place of where I went to school,” Rucker said. “When I was younger, my parents taught me the values and to impact as many people as you’re able to influence. I think that just naturally carried on with me and allowed me to have a giving heart.”

“Let me use my platform, my social media presence, my football presence. Let me use my name to help people out, to influence

people, to give back if I had the opportunity, whether that was physically, whether that is talking to them, financially, whatever I can do to give back,” he continued. “To be honest, [the Witten award] is bigger to me than any other physical accolade I hope to get this season. Not only did I do my thing on the field, but it also shows the commitment that I gave myself off the field to do whatever I can to influence the youth and my community.”

Citing both his parents as some of the most influential people in his life, Rucker noted the significance it would have if he could win the Witten Man of the Year award.

“I don’t want to win this award just to win it. It would just mean a lot, just the commitment that I’ve given myself to be the best person that I can be,” he said. “This something that my mom and dad can look back over and be like, ‘Dang, this is something that our son did.’ It would mean the world to me to win this award and to give it to my mom and dad knowing that I gave it all I had in the community as well as on the field.”

WWhen I was 19, and a sophomore at Carolina, I did the dumbest thing imaginable. I decided to become a writer. I liked Hemingway, Faulkner, and O’Connor, of course, but I loved Cormac McCarthy. I wanted to be like him.

When I got out of Carolina, I moved to New York to write a novel. Nobody tried to talk me out of this. Looking back, not a single adult in my life warned me about the path I was taking, a path without maps, prospects, or much chance of success. The sum total of my father’s career advice was: If you go to law school, I’ll kill you.

But I was the hero of my own story, so I went up to literary New York, in 1992, where I worked two jobs, slowly starved, and wrote at night and on the weekends.

After a year, I finished a draft. 337 pages. I read it back and realized I was doomed. It was terrible. So bad. Just a bad imitation of my hero McCarthey. I wasn’t good enough.

I burned it. I thought about law school. It was 1993. The Montross year. The Fab Five Year. The Time Out year.

A week after the Burning of the Book, floating in a state of limbo, I was on the brink of calling it quits on the writing life.

It was also the week of the title game in New Orleans.

After we won, I went out to a BBQ joint a bunch of Carolina guys owned on the Upper East Side. I could not afford the Upper East Side, or barbecue. I spent the last of the reserves getting hammered with happy Tar Heels. It was pure joy, something I was not feeling a lot of.

I vaguely remember leaving the bars at first light, and going to a news kiosk, buying up all the papers for the sports pages.

It was too late to go to my apartment so I went straight to work in my beer soaked clothes. I read every article in every paper about the Tar Heel championship in a hungover stupor. I was thrilled at the grit of Big Grits, the cool determination of Donald Williams. Inspired, I decided not to quit writing, not just yet. Two years later my brother and I wrote and directed our first movie.

I wouldn’t have kept going if it wasn’t for the Heels. But that was just the first of the many life lessons I’ve learned from the basketball program. There’ve been several other Tar Heel greats who I’ve turned to for inspiration. I can think of three distinct examples.

For Fortitude and Will, perhaps the most vital component to success in writing, I was inspired by Tyler Hansbrough. He was not the biggest, not the best, he was just the guy who would work harder, the guy who wanted it more. If Psycho T could work that hard, I could work that hard. What’s another revision? Who cares? Just win.

For Leadership by Example, a key aspect to leading a film

crew, I looked to George Lynch. George did all the little things right. Rose to moments of crisis. He did everything, and nothing, leading the team without the team realizing he was doing it.

For Selfless Service to the Greater Goal, it was Jackie Manuel, locking people up on defense. Others got more credit and attention, Jackie did the most important job -- render the opposition’s biggest threat totally impotent. Who cares who gets the credit.

I’d see all of them and think, I can do better. I can work harder. I can be more.

It wasn’t just the players, of course, it was the overall hoops culture: the discipline, love, honor and ultra-competence of the staff, from Dean to Roy to Hubert.

To this day, I approach organizing a film crew along the Carolina Way. Organized, supportive, all the while demanding excellence and accountability. It might seem strange that a college hoops program is actually an ETHICS program, but it is what it is.

One more bit of my story.

The origin of Outer Banks was, in fact, a direct result of the Redeem Team of 2017. During the run, I had reconnected with an old friend, Shannon Burke, who graduated from Carolina a few years before me. He had become a novelist -- we often shared manuscripts for advice. We had been friends for decades but never worked together.

The Redeem Team’s run sparked a series of late night phone conversations where we broke down the latest battle. It intensified as we neared the title. We could both sense they were going to do it. And then of course, we won. The next day, for the first time, having been friends for twenty years, I said to Shannon, you know, we should try to come up with a story together. So

JOSH PATE

Writer & Producer