ARCHITECTURE

CANADA 2018

RAIC Coordinators / Coordination à l’IRAC Chantal Charbonneau

Maria Cook

Translators / Traductrices

Myriam Legault-Beauregard, Canada Council for the Arts / Conseil des arts du Canada

France Jodoin, certified translator / traductrice agréée

Jennifer Strachan, M.A., certified translator / traductrice agréée (ATIO)

Design / Conception graphique

Vicky Coulombe-Joyce, TANDEM

Printing / Impression

Gilmore Printing Services Inc.

© Royal Architectural Institute of Canada

All Rights Reserved. Published in September 2018

Printed in Canada

© Institut royal d’architecture du Canada

Tous droits réservé. Publié en septembre 2018

Imprimé au Canada

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA CATALOGUING DATA

DONNÉES DE CATALOGAGE DE LA BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE DU CANADA

Architecture Canada

Biennial

Published: Ottawa, Ontario

Includes text in French

Continues: Governor General’s Awards in Architecture, 1189-6388

Ouvrage biennal.

Publié à Ottawa, Ontario

Comprend du texte en français

Ancien titre : Prix du Gouverneur général pour l’architecture, 1189-6388

ISSN 1209-7136

ISBN 978-0-919424-66-1 (2018)

1. Governor General’s Medals in Architecture Médailles du Gouverneur général en architecture

2. Architecture, Modern – 20th Century –Canada

Architecture, Moderne – XXe Siècle – Canada

3. Architecture – Awards – Canada

Architecture – Prix – Canada

PARALLELOGRAM HOUSE

5468796 Architecture Inc.

BORDEN PARK PAVILION gh3

FORT McMURRAY INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT

office of mcfarlane biggar architects + designers inc. (omb)

FORT YORK VISITOR CENTRE

Patkau Architects Inc. /

Kearns Mancini Architects Inc.

MICHAL AND RENATA HORNSTEIN PAVILION FOR PEACE

Atelier TAG + Jodoin Lamarre

Pratte architectes en consortium

CASEY HOUSE

MAISON DE LA LITTÉRATURE

Chevalier Morales Architectes

TWO HULLS HOUSE

MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects

RABBIT SNARE GORGE

Omar Gandhi Architect Inc. in collaboration with Design Base 8 (NYC)

Hariri Pontarini Architects STADE

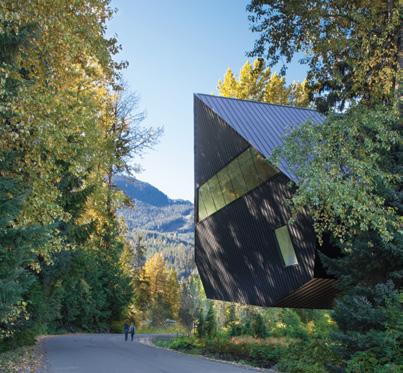

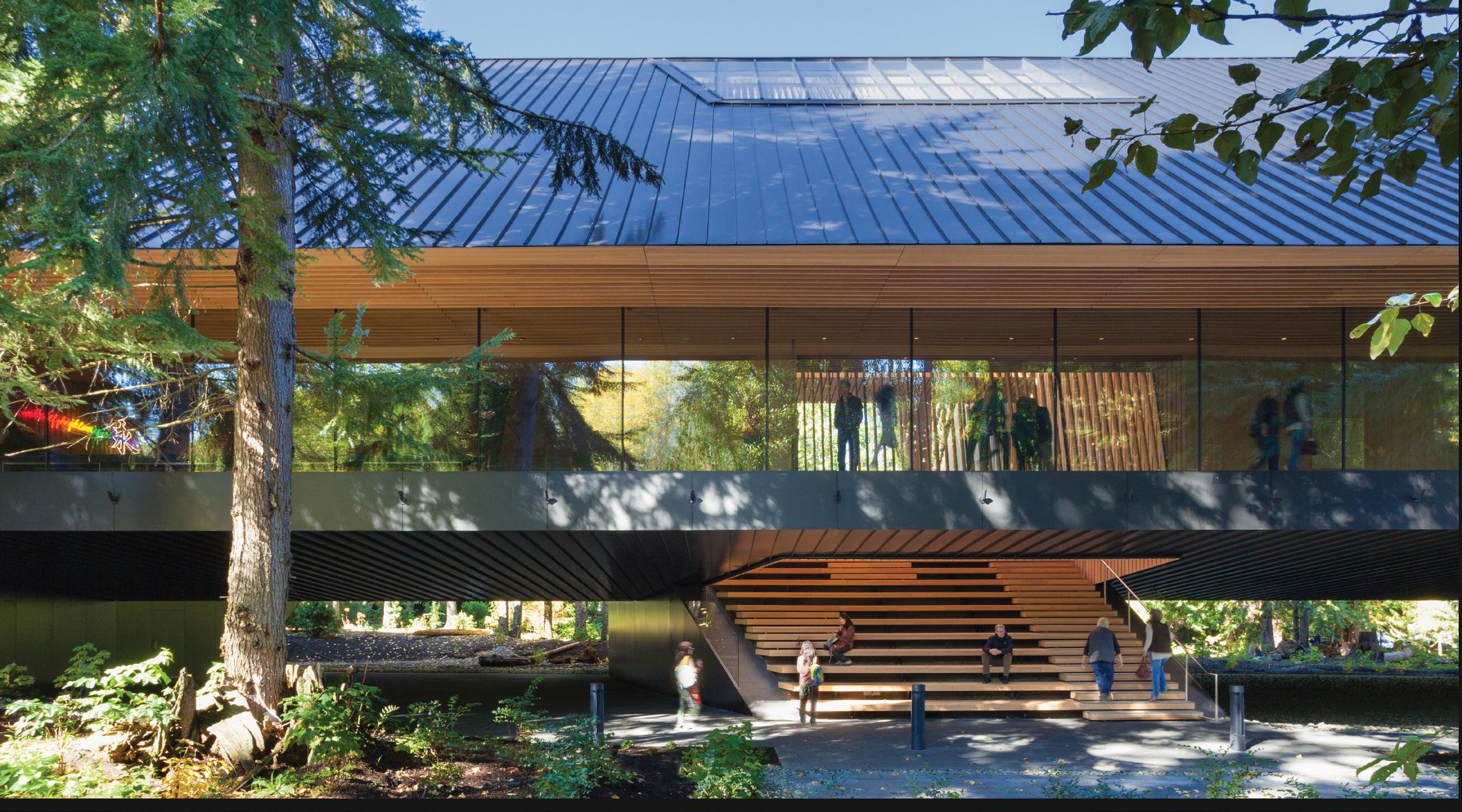

AUDAIN ART MUSEUM

Patkau Architects

COMPLEXE SPORTIF

SAINT-LAURENT

SAUCIER+PERROTTE / HCMA Architecture + Design

CONTENTS

TABLE DES

Foreword Avant-propos

Preface

Préface

Message

Message

Governor General’s Medals 2018: Jury Essay

Médailles du Gouverneur général 2018 : mot du jury

Medals Médailles

The Jury Le jury

Acknowledgements Remerciements

Firms Les architectes

It is my great pleasure to offer my heartfelt congratulations to all the recipients of this year’s Governor General’s Medals in Architecture, which are presented today by Her Honour the Honourable Janice Filmon, Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba.

Architecture plays an essential and ennobling role in our world. The best architects create structures that strike our imagination, broaden our minds and stand the test of time. They transform the environments in which we live, work and play in moving and inspiring ways. Each of the architects being honoured today, whether individually or as members of a creative team, has made an outstanding contribution to their field.

Let us warmly applaud the medal winners, whose talent, vision and innovative spirit have gifted our country with exceptional creations.

Je tiens à féliciter chaleureusement tous les lauréats de la Médaille du Gouverneur général en architecture, qui leur est remise aujourd’hui par Son Honneur l’honorable Janice Filmon, lieutenante-gouverneure du Manitoba.

L’architecture joue un rôle noble et essentiel dans notre monde. Les meilleurs architectes créent des structures qui frappent l’imagination, élargissent nos horizons et transcendent le temps, par des ouvrages qui nous touchent et qui transforment les milieux dans lesquels nous vivons, travaillons, étudions et nous divertissons. Chacun des créateurs que nous honorons aujourd’hui, individuellement ou au sein d’équipes remarquables, a réalisé des œuvres exceptionnelles.

Applaudissons les médaillés, dont le talent, la vision et l’esprit d’innovation nous enrichissent comme Canadiens par leurs créations uniques et inspirantes.

Julie Payette 2018

The 2018 Governor General’s Medal’s in Architecture recipients demonstrate excellence of design and diversity of purpose. In each of the winning projects, it’s clear that the special qualities of the sites have been a source for the architecture, with the architects drawing inspiration from cultural and natural history.

It is encouraging to see that many of the winners are buildings designed for the public and are in daily use, whether for healing, playing sports, finding books and art, visiting a tourist site, or enjoying a city park.

The RAIC is proud to advocate for the quality of our environments by recognizing these examples of the best contemporary architecture in Canada.

Les lauréats des Médailles du Gouverneur général en architecture de 2018 démontrent l’excellence dans le design et dans la diversité des utilisations. Dans chacun des projets gagnants, il est clair que les qualités particulières des sites ont été une source d’inspiration pour l’architecture, les architectes s’inspirant de l’histoire culturelle et naturelle. Il est encourageant de constater que bon nombre des projets gagnants sont des bâtiments conçus pour le public et sont utilisés quotidiennement, que ce soit pour la guérison, la pratique de sports, la recherche de livres et d’œuvres d’art, la visite d’un site touristique ou d’un parc municipal.

L’IRAC est fière de défendre la qualité de nos environnements en reconnaissant ces exemples de la meilleure architecture contemporaine au Canada.

Michael Cox, FRAIC President / Président

MESSAGE MESSAGE

The Canada Council for the Arts salutes the 2018 Medal winners!

The Canada Council for the Arts is committed to the ongoing support, promotion and recognition of artistic and literary creation, and to engaging Canadians in the process. This includes its work to champion architecture as an art form that has a profound and lasting effect on people in their daily lives. Great architecture can inspire us, move us, soothe us, and transport us to other realms.

The Canada Council is pleased to contribute once again to the Governor General’s Medals in Architecture through its trusted system of peer assessment. The winners of the 2018 Governor General’s Medals in Architecture can be justly proud that they have designed places that, for instance, motivate athletes to surpass themselves, appease the suffering of people grappling with illness, and build bridges to the past. These winners have not been afraid to break with convention.

To all of the 2018 Medal winners, we extend our warm congratulations, our thanks for your contribution to elevating the standard of our built environment, and our best wishes for ongoing achievement in your careers.

Le Conseil des arts du Canada félicite les lauréats des médailles de 2018!

Le Conseil des arts du Canada est déterminé à soutenir, à promouvoir et à reconnaître la création artistique et littéraire sur une base permanente et, ce faisant, à favoriser l’engagement des Canadiennes et des Canadiens. Il défend notamment le statut de l’architecture en tant que forme d’art qui a un effet durable sur la vie quotidienne des gens. L’architecture a le pouvoir de nous inspirer, de nous émouvoir, de nous apaiser et de nous transporter ailleurs.

Le Conseil des arts du Canada est heureux de contribuer une fois de plus aux médailles du Gouverneur général en architecture, par l’entremise de son rigoureux système d’évaluation par les pairs. Les gagnants de cette année peuvent être fiers, puisqu’ils fournissent des lieux qui poussent les athlètes à se dépasser, mettent un baume sur les souffrances de personnes qui doivent composer avec la maladie, construisent des ponts entre le passé et le présent. Ils n’ont jamais hésité à briser les conventions.

À tous les lauréats des médailles de 2018, nous offrons nos plus sincères félicitations, nos remerciements pour leur contribution à l’amélioration de notre environnement bâti, et nos meilleurs souhaits pour leur carrière et leurs réalisations en cours.

Simon Brault Director and CEO / Directeur et chef de la direction

The Governor General Medals in Architecture are an extrapolation not only of some of the most exceptional projects of our era, but the broad spectrum of our collective values at a given moment. The eligibility period is long, allowing for consideration any project by a Canadian architect that has been completed within the past seven years; the period of adjudication is short and very intense 48 hours. The relatively quick selection within a long fermentation period has a particular effect on the results, as does the requirement to name a specific number of winning projects. This allows space for “wild cards”—smaller projects of nonconformist qualities, which can be seen more as compact experiments than paradigms. It also can give more complex, remote or contentious projects more time to prove their worth, become known and renowned, to gestate and mature within the global architectural landscape. This year, the selection of Governor General Medal projects is notably wide-ranging, from an international airport to a small hospital to a tiny park pavilion to an art museum. A discernable trend is the representation of projects that address the challenges of difficult or unconventional sites—in some cases transforming what would conventionally be seen as a geographical problem. In Whistler, the Audain Art Museum is a brilliant response to building in the woods and over a floodplain; in Montreal, the Stade de soccer is built above a former quarry and dumping site. In Toronto, the Fork York Visitor Centre deftly fits into a narrow “found site” alongside the abutments of an expressway. And the Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion for Peace at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts is in large part a functional stairway that doubles as a social gathering

Les médailles du Gouverneur général en architecture ne sont pas seulement un échantillon de projets parmi les plus exceptionnels de notre époque. Ils représentent aussi l’extrapolation du vaste spectre de nos valeurs collectives à un instant donné. La période d’admissibilité est longue, ce qui permet de considérer tout projet complété par un architecte canadien au cours des sept dernières années. En comparaison, les 48 heures accordées aux délibérations constituent un intervalle très court et très intense. Cette sélection relativement rapide, assortie d’une longue période de fermentation, a un effet particulier sur les résultats, tout comme l’obligation de nommer un nombre précis de projets gagnants. Cela permet à des projets « imprévisibles » — soit des projets de plus petite envergure aux qualités non conformistes, qui peuvent être vus davantage comme des expérimentations compactes que comme des paradigmes — de se tailler une place. Cela donne aussi l’occasion à des projets plus complexes, controversés ou situés en région éloignée de prouver leur valeur, de se faire connaître et reconnaître, et de prendre de la maturité au sein du paysage architectural mondial. Cette année, la sélection de projets gagnants d’une médaille du Gouverneur général est remarquablement diversifiée. Elle va d’un aéroport international à un petit hôpital, en passant par un minuscule pavillon de parc et un musée d’art. Une tendance observable est la représentation de projets qui s’attaquent aux défis de sites difficiles ou non conventionnels. Dans certains cas, ils arrivent même à transformer ce qui serait normalement considéré comme un problème géographique. À Whistler, le Musée d’art Audain répond brillamment à son environnement : il est bâti dans les bois, au-dessus de plaines inondables. À Montréal, le Stade de soccer est construit sur une ancienne carrière

space. None of these approaches defy the basic tenets of modernism, which compel an architect to make the best and most logical use of existing conditions and materials, but they exemplify its qualitative value.

Each project suggests a reconsideration as to what constitutes an appropriate architecture and a buildable site.

This phenomenon is no doubt propelled in part by the inexorable pressure on land prices across Canada, a pressure that has widely encouraged the reconsideration of sites once deemed undesirable or unbuildable. The logistical challenges of building on such sites has by necessity required an especially creative—almost experimental—design approach, which can encourage the wider community to rethink what defines a property as “valuable.” A seasonal flood plain leads to a museum that is essentially a bridge as well as a building. A decommissioned quarry becomes the perfect raw setting for the muscular architecture of a soccer stadium. Concrete roadway abutments and berm generate the unusual topography that heightens the sense of pilgrimage to a historic site. And a gallery’s expansion is shoehorned into an urban space so tight that there is no option but for every square inch to serve multiple purposes—which enlivens and enriches a stairway’s otherwise-utilitarian programme.

Two of the selected projects are expansions and transformations of heritage structures, albeit in dramatically different approaches. Maison de la littérature in Quebec City expands and utterly transforms a 19th-century heritage church into a starkly white, audaciously open and highly contemporary arena for reading, writing and research. Conversely, the Casey

et décharge. À Toronto, le Centre d’accueil des visiteurs du Fort York s’insère adroitement dans un étroit « site trouvé », côtoyant les piliers d’une autoroute. De son côté, le Pavillon pour la Paix Michal et Renata Hornstein, au Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, est en grande partie un escalier fonctionnel qui sert de lieu de rassemblement social. Aucune de ces approches ne conteste les principes de base du modernisme, qui poussent un architecte à faire l’usage le plus profitable et le plus logique possible des conditions et des matériaux existants, mais ils sont l’illustration de sa valeur qualitative.

Chaque projet suggère une révision de ce qui constitue une architecture appropriée et un site bâtissable.

Ce phénomène est sans aucun doute amplifié en partie par la pression inexorable qui s’exerce sur les prix des terrains au Canada, pression qui a largement mené à la reconsidération de sites jadis jugés indésirables ou impropres à la construction. Les défis logistiques de bâtir sur chacun de ces sites ont par nécessité requis une approche du design particulièrement créative — presque expérimentale — qui encourage la communauté au sens large à repenser ce qui fait la « valeur » d’une propriété. Une plaine inondée au fil des saisons mène à un musée qui est essentiellement un pont, en plus d’être un édifice. Une carrière désaffectée devient, dans sa forme brute, le lieu idéal pour l’architecture musclée d’un stade de soccer. Les piliers de béton d’une autoroute et la forme de talus génèrent une topographie inhabituelle qui renforce le sentiment de pèlerinage que confère un site historique. Et le prolongement d’une galerie est comprimé dans un espace urbain si serré qu’il n’y a pas d’autre option que de donner plusieurs rôles à chaque centimètre carré, ce qui anime et enrichit les fonctions normalement utilitaristes d’un escalier.

GOVERNOR GENERAL’S MEDALS 2018: JURY ESSAY

MÉDAILLES DU GOUVERNEUR GÉNÉRAL 2018 : MOT DU JURY

House hospital consists of a modernist expansion characterized by an ambiance of intimacy, care and protection, a haven affixed to a conservative restoration of a 19th-century mansion. The disparity in the kind and level of intervention reminds us that the reformatting of older buildings defies formulaic resolution.

Along with difficult sites are “easy” but banal sites, in remote communities and big-city suburbs, the surrounding monotony being one of the challenges to designing a memorable structure. The remote Fort McMurray, an isolated community of largely transient workers who’s International Airport brings rigour and grace to a remote locale. In the Montreal suburb of Saint-Laurent, the sprawl that surrounds the new Saint-Laurent Sports Complex is enlivened and activated by the new architectural presence.

While the aforementioned projects entail a considerable degree of complexity in their site-planning, design and construction, the jury also recognized a notable number of smaller projects of relative simplicity. Among these is Edmonton’s Borden Park Pavilion, a low-slung cylinder that visually blends into its verdant surroundings by day and then illuminates them by night, in surreal fashion. This is not an epic project, but more of a sign of a cipher arguing for the privileging of public space, parkland and social connection, an architectural correlative to an important and timely subject.

The collective decision to recognize three single-family houses, in an age where this typology has been both demonized as ecologically unsustainable but simultaneously fetishized by the global marketplace, was reached only after a period of intense discussion. The detached house remains a mainstay both as

Deux des projets sélectionnés sont des prolongements et des transformations de structures patrimoniales, mais réalisés selon des approches totalement différentes. La Maison de la littérature de Québec agrandit et transforme radicalement une église patrimoniale du XIXe siècle en un espace tout blanc, audacieusement ouvert et très contemporain réservé à la lecture, à l’écriture et à la recherche. Inversement, l’hôpital de la Maison Casey est un prolongement moderniste caractérisé par une ambiance d’intimité, de soins et de protection; un havre annexé à un manoir du XIXe siècle restauré de façon conservatrice. La disparité dans le type et le degré d’intervention nous rappellent que la refonte d’anciens édifices défie les résolutions conventionnelles.

En plus des sites difficiles, il y en a d’autres qui sont « faciles », mais banals, dans des communautés éloignées et des banlieues de grandes villes. La monotonie environnante est alors l’un des principaux défis à la conception d’une structure mémorable. La communauté isolée de Fort McMurray, dont la majorité des travailleurs est de passage, est maintenant dotée d’un aéroport international qui lui apporte rigueur et grâce. Dans la banlieue montréalaise de Saint-Laurent, l’étalement urbain qui entoure le nouveau Complexe sportif est vivifié par cette nouvelle présence architecturale.

Bien que les projets mentionnés ci-dessus impliquent un degré considérable de complexité dans leur planification, leur design et leur construction, le jury a aussi reconnu un nombre notable de plus petits projets d’une relative simplicité. Parmi ceux-ci, citons le Pavillon du parc Borden, à Edmonton, un bas cylindre qui se fond visuellement dans les environs verdoyants durant la journée, puis les illumine la nuit, de façon surréaliste. Il ne s’agit pas là d’un projet grandiose,

a primary residence and a rural retreat, but in most cases designed and built so predictably that they are invasive species upon the city and the seaside. As a society, we are not collectively prepared to give up the detached house. In an age where houses in Canadian cities are increasingly designed, built and sold like stock options, the jury recognized three houses that resist commodification.

These Medal-winning houses are not large, and—aside from the audaciously cantilevered Two Hulls House—not particularly expensive to build. Also selected was Parallelogram House, an otherwise-ordinary home in the suburbs of Winnipeg, with an angular massing and materials, including steel, that are normally associated with more edgy, urban environments; and Rabbit Snare Gorge, a Cape Breton home of uncanny proportions. Two Hull House, the most complex and dramatic design of the three, breaks from the formulaic trope of long glass box along the waterfront; the structure is literally cantilevered over the ocean, deferring to as well as engaging with it. It is an approach that is conceptually similar to that of the Audain Art Museum: the way in which these structures are positioned over the site has rendered their dialogue with it all the more poetic and powerful.

Architects still have more leeway in exploring and defying existing conventions in detached houses in low-density regions than in the housing type that is more crucial for our economic and ecological future: the multi-unit residential building, none of which feature among the Medalists this year. One can hope for a future wherein our political leaders and our socio-economic model will favour and support true design innova-

mais plutôt d’un message codé qui défend les bienfaits des espaces publics, des parcs et des liens sociaux, d’un élément architectural qui correspond à un enjeu important et actuel.

La décision collective de reconnaître trois maisons unifamiliales, à une époque où ce type d’habitation est à la fois diabolisé, vu son côté non écologique, et adulé par le marché mondial, n’a été prise qu’après une période d’intenses discussions. La maison individuelle demeure un incontournable, tant comme résidence principale que comme retraite rurale, mais dans la plupart des cas, elle est conçue et bâtie avec tant de prévisibilité qu’elle représente une espèce envahissante pour les villes et les bords de mer. En tant que société, nous ne sommes pas prêts à renoncer à la maison individuelle. Alors que les maisons, dans les villes canadiennes, sont de plus en plus conçues, bâties et vendues comme des titres boursiers, le jury a reconnu trois maisons qui résistaient à la marchandisation.

Les maisons médaillées ne sont pas grandes, et à part la maison aux deux coques, bâtie audacieusement en porte-à-faux, elles ne sont pas particulièrement coûteuses à bâtir. Ont aussi été sélectionnées la Résidence parallélogramme qui, outre sa forme, est assez conventionnelle, construite en banlieue de Winnipeg avec des matériaux angulaires, y compris de l’acier, qui sont normalement associés à des environnements plus avant-gardistes et urbains; et le chalet dans la gorge du piège à lapins, une résidence du Cap-Breton aux proportions étonnantes. La maison aux deux coques, dont le design est le plus complexe et la plus spectaculaire des trois, s’éloigne du cliché de la longue maison vitrée qui s’étend sur le littoral. Sa structure est en porte-à-faux au-dessus de l’océan, lui rendant hommage et interagissant avec lui. Conceptuellement

GOVERNOR GENERAL’S MEDALS 2018: JURY ESSAY

MÉDAILLES DU GOUVERNEUR GÉNÉRAL 2018 : MOT DU JURY

tion in this typology, but that is not the circumstances in which we are currently living.

The eligibility criteria allow for projects built in other countries, although this year all 12 Medals happen to honour projects built within Canada. This is largely happenstance, but also a sign of a current embrace of proximity and pragmatism. Canadian architects have produced a wealth of masterful cultural buildings in recent years, at home and afar, and not all of them are represented in this current array of Medals. The Governor General Medals are not a fixed and quantifiable measure of worth, but rather as a freeze-frame of today’s measure. Meanwhile, a wider and deeper appreciation of built projects of enduring brilliance will continue to gestate.

—Adele Weder

parlant, cette approche est semblable à celle du Musée d’art Audain : la façon dont les structures sont positionnées au-dessus du site a rendu leur dialogue avec celui-ci tout aussi poétique que puissant.

Les architectes ont toujours plus de jeu pour explorer et défier les conventions existantes avec des maisons individuelles dans des régions peu peuplées qu’avec des types d’habitation qui sont plus cruciales pour notre avenir économique et écologique : les édifices résidentiels à plusieurs logements, dont aucun représentant n’a été médaillé cette année. On peut espérer qu’à l’avenir nos dirigeants politiques et notre modèle socioéconomique favoriseront et appuieront de véritables innovations en design dans ce type d’habitations, mais ce ne sont pas encore les conditions dans lesquelles nous évoluons à l’heure actuelle.

Les critères d’admissibilité permettent à des projets bâtis dans d’autres pays d’être considérés, mais cette année, les 12 médailles honorent des projets bâtis au Canada. C’est surtout un hasard, mais aussi un signe de notre attachement actuel pour la proximité et le pragmatisme. Les architectes canadiens ont produit d’une main de maître une grande richesse d’immeubles culturels au cours des dernières années, au pays et à l’étranger, mais aucun d’entre eux n’est représenté parmi les médaillés de cette année. Les médailles du Gouverneur général en architecture ne sont pas une mesure de valeur fixe et quantifiable, mais plutôt un arrêt sur image de la mesure du temps. En attendant, une appréciation plus large et plus vaste des projets bâtis assortis d’une brillance durable continuera de mûrir.

—Adele Weder

PROJECT / PROJET

OCCUPATION DATE / DATE D’OCCUPATION

September 2014 / Septembre 2014

ARCHITECT / ARCHITECTE

Lead Design Architects / Principaux architectes concepteurs :

Sasa Radulovic and Aynslee Hurdal

ARCHITECTURAL FIRM / CABINET D’ARCHITECTES

5468796 Architecture Inc.

PROJECT TEAM / ÉQUIPE DE PROJET

Apollinaire Au, Pablo Batista, Ken Borton, Jordy Craddock, Ben Greenwood, Aynslee Hurdal, Johanna Hurme, Caroline Inglis, Andriy Ivanytskyy, Jeff Kachkan, Eva Kiss, Stas Klaz, Lindsey Koepke, Kelsey McMahon, Colin Neufeld, Simone Prill, Sasa Radulovic, Sean Radford, Hugh Taylor, Trent Thompson, Matthew Trendota, Shannon Wiebe, Jenn Yablonowski

CLIENT / CLIENT

Nolan and Rachel Ploegman

CONSULTING TEAM / EXPERTS-CONSEILS ET AUTRES INTERVENANTS

Structural Engineer / Ingénierie structurale : Hanuschak Consultants Inc.

Builder / Constructeur : Concord Projects

Landscape Architect / Architecte-paysagiste : Scatliff + Miller + Murray

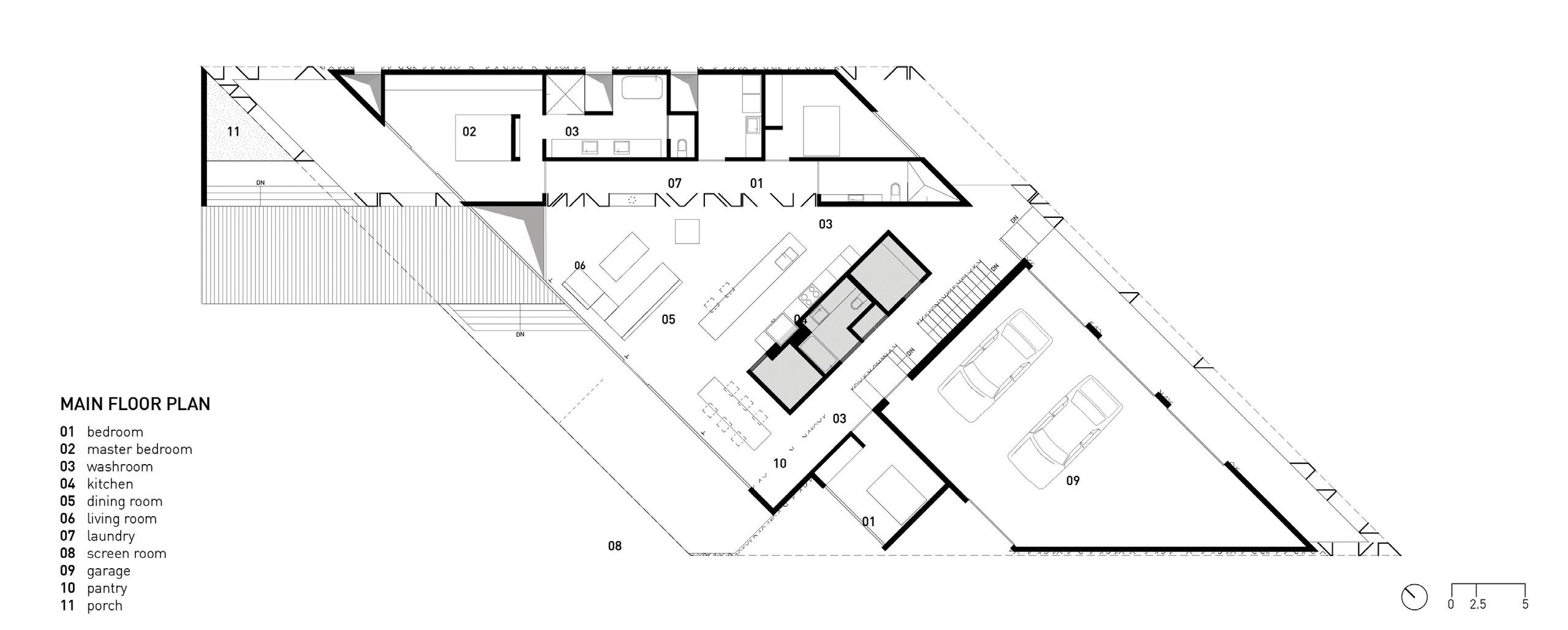

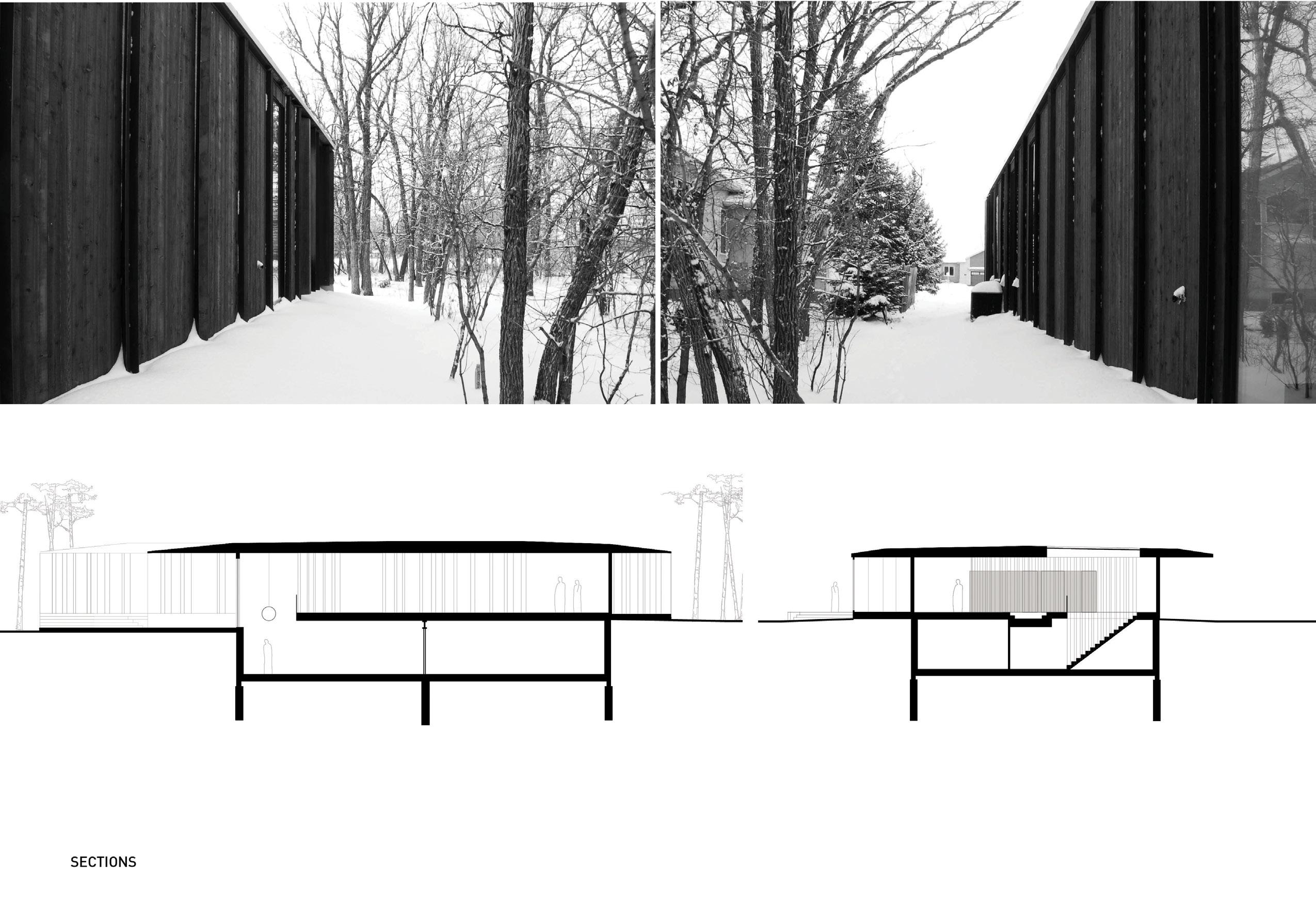

Designed for a family of four, the Parallelogram House is located in East St. Paul, a bedroom community just north of Winnipeg. Situated on a typical suburban street, the home stands in quiet and refined contrast to its stucco-clad neighbours. It is characterized by an unorthodox form and unexpected materials that are at once inconspicuous and yet architecturally significant.

Since the neighbourhood was developed 30 years ago, the property has not been touched. It is a remnant site beside a thick stand of existing trees with a public walking and cycling trail beyond. The clients were drawn to the potential of the site as a generous and shaded outdoor sanctuary and a tranquil clearing where they could settle their family and build campfires with their children.

While the clients desired a bungalow, they also wanted to ensure that all the rooms had views of the front or backyard. Based on the lot size, setbacks, and the frontage requirements, the program could only fit within a two-storey volume. By skewing of the floor plan into a parallelogram, the window area was increased by almost 1.5 times without increasing the footprint. This strategy opened the home to a panoramic view of the tree preserve and welcomed the southern exposure into the site and home.

On the exterior, the house is clad in naturally stained wood siding that wraps onto the underside of the roof overhang above. The overhang covers open patios and a screened porch, supported by a series of u-shaped Cor-Ten plate steel columns. These columns extend the rich texture and long shadows of the surrounding trees and serve to screen private rooms.

RÉSIDENCE PARALLÉLOGRAMME

Conçue pour une famille de quatre personnes, la résidence parallélogramme est située sur une rue typique de Saint-Paul Est, une banlieue-dortoir au nord de Winnipeg. La maison contraste avec ses voisines revêtues de stuc par sa discrétion et son raffinement. Elle se caractérise par sa forme originale et l’utilisation de matériaux inhabituels qui sont parfois peu visibles, mais qui ont tout de même une importance architecturale.

Depuis que le quartier s’est développé, il y a 30 ans, le terrain était resté intouché, à proximité d’un épais bouquet d’arbres, d’un sentier pédestre et d’une piste cyclable. Les clients ont été attirés par le potentiel du site qu’ils voyaient comme un sanctuaire extérieur généreux et ombragé et un endroit tranquille où ils pourraient établir leur famille et faire des feux de camp avec leurs enfants.

Ils désiraient un bungalow, mais ils voulaient aussi que toutes les pièces donnent sur l’avant ou sur la cour arrière. En tenant compte des dimensions du terrain, des marges de recul et des exigences relatives aux façades, le programme ne pouvait fonctionner que dans un volume de deux étages. En donnant au plan d’étage la forme d’un parallélogramme, il a été possible d’augmenter d’une fois et demie la superficie des fenêtres sans augmenter l’empreinte au sol. Cette stratégie a permis d’orienter la maison vers le sud et d’offrir à ses occupants une vue panoramique sur le boisé.

À l’extérieur, un parement en bois de teinte naturelle recouvre la maison et le dessous du débord de toit.

Le débord de toit surplombe les terrasses ouvertes et une véranda avec moustiquaire et il est soutenu par une série de colonnes en U en plaques d’acier Corten.

PARALLELOGRAM HOUSE

RÉSIDENCE PARALLÉLOGRAMME

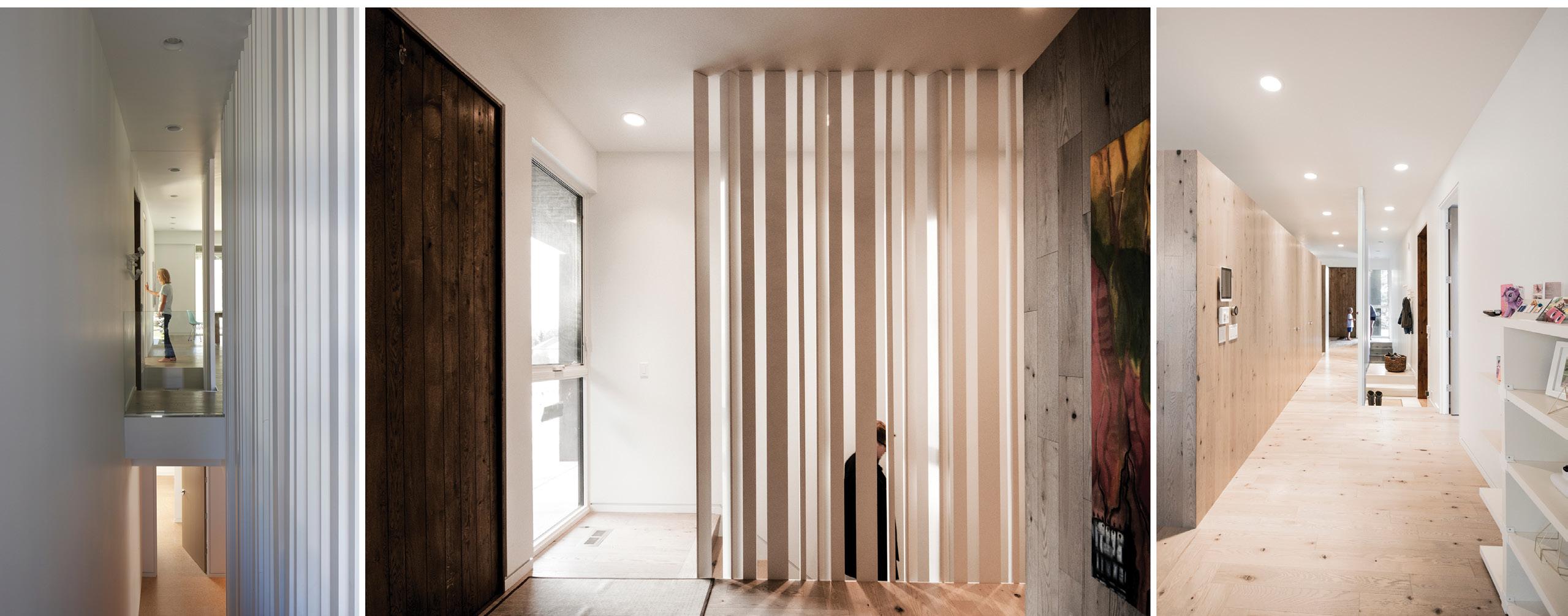

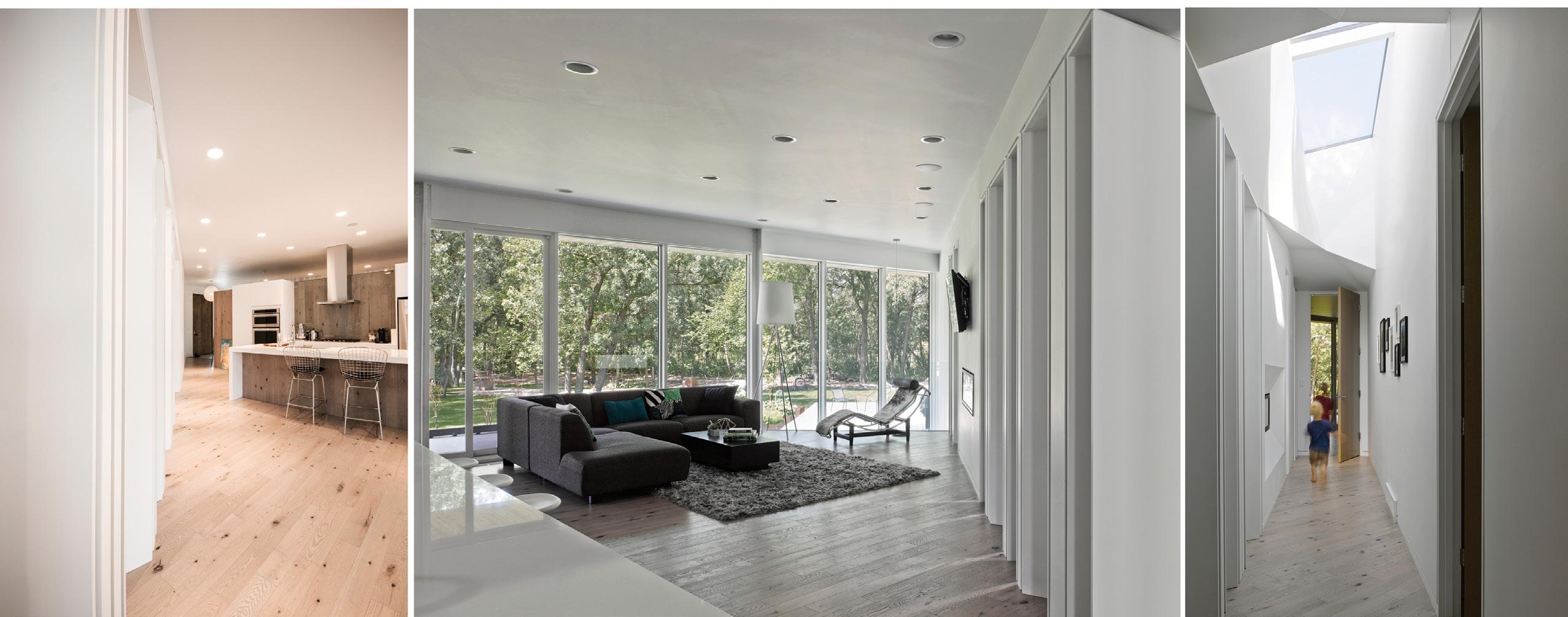

Together, the dark palette of wood and steel ground this quiet residence into its surrounding landscape. Inside, high ceilings and an open plan define the main living space. The plan flows around a freestanding utility box which contains the kitchen pantry as well as a walk-in closet and bathroom. The wood-clad box grows upwards from the floor and helps define the spaces around it. A simple and muted palette emphasizes the interior volumes with a sequence of light wells and skylights that draw daylight from the main floor all the way down to the basement. The bedroom wing is separated from the living space by a white steel screen that extends the geometry and function of the exterior columns into and throughout the house.

Ces colonnes prolongent la riche texture et les longues ombres des arbres environnants et servent d’écran aux pièces privées. La palette foncée de bois et d’acier ancre cette résidence intimiste dans le paysage qui l’entoure.

À l’intérieur, les hauts plafonds et le plan ouvert définissent les principaux espaces de vie. Le plan s’articule autour d’un îlot de service séparé qui contient le comptoir de cuisine ainsi qu’une pièce-penderie et une salle de bains. L’îlot revêtu de bois s’étend en longueur et définit les espaces qui l’entourent. Une palette simple et discrète met l’accent sur les volumes intérieurs avec une séquence de puits de lumière et de lucarnes qui apportent la lumière du jour du rez-de-chaussée jusqu’au sous-sol. L’aile des chambres est séparée des espaces de vie par un écran d’acier blanc qui prolonge la géométrie et la fonction des colonnes extérieures dans toute la maison.

RÉSIDENCE PARALLÉLOGRAMME

At once radical and subtle, Parallogramme House experiments with the context of ordinary suburban architecture. Its diagonal facades front and back afford more expansive and yet more private view lines than the ubiquitous and non-private in-line siting of houses in residential neighbourhoods. Its use of steel fins provides a provocative alternative both in material and form to the predictable and banal materials that are more common to the programme. This is domestic architecture that challenges its paradigm, and yet with its single-story height and earth-toned façade, it maintains a low profile.

À la fois radicale et subtile, la résidence Parallogramme expérimente le contexte de l’architecture de banlieue ordinaire. Ses façades en diagonale à l’avant et à l’arrière offrent des points de vue plus étendus et assurent une plus grande privauté que les maisons omniprésentes des quartiers résidentiels environnants dont l’implantation laisse peu de place à la vie privée. Son utilisation d’ailettes en acier offre une solution de rechange provocatrice, tant sur le plan des matériaux que de la forme, à la banalité des matériaux généralement utilisés dans la construction résidentielle. Ce projet d’architecture domestique remet son paradigme en question et il reste discret du fait qu’il se déploie sur un seul étage et qu’il est dans des tons de terre.

PROJECT / PROJET

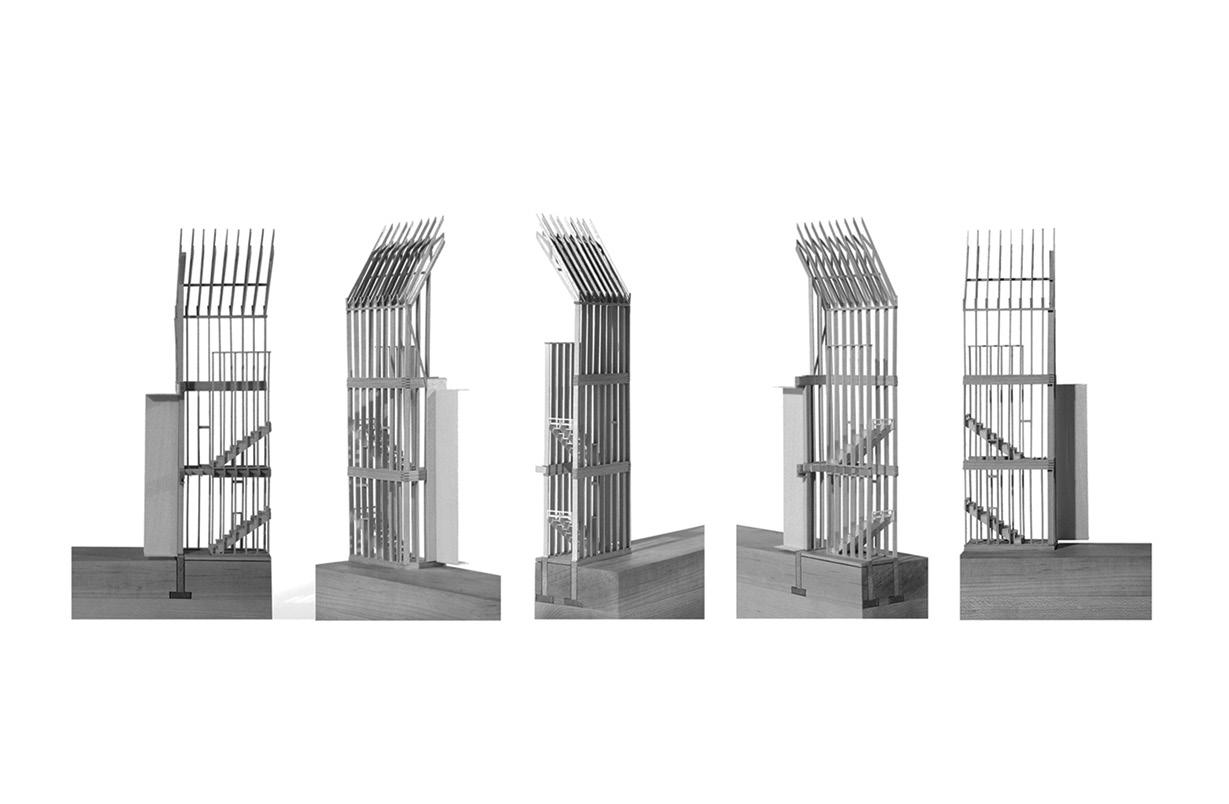

MICHAL AND RENATA HORNSTEIN PAVILION FOR PEACE –

MONTREAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

MONTREAL, QUEBEC, CANADA

PAVILLON POUR LA PAIX MICHAL ET RENATA HORNSTEIN –

OCCUPATION DATE / DATE D’OCCUPATION

November 2016 / Novembre 2016

BUDGET / BUDGET

$23.7 M / 23,7 M$

ARCHITECT / ARCHITECTE

Lead Design Architects / Principaux architectes concepteurs :

Manon Asselin (Atelier TAG)

ARCHITECTURAL FIRM / CABINET D’ARCHITECTES

Atelier TAG + Jodoin Lamarre Pratte architectes en consortium

PROJECT TEAM / ÉQUIPE DE PROJET

Manon Asselin, architect principal (Atelier TAG), Katsuhiro Yamazaki, architect principal (Atelier TAG), Pawel Karwowski, artistic director (Atelier TAG), Benjamin Rankin, architect (Atelier TAG), Mathieu Lemieux-Bouchard, graduate architect (Atelier TAG), Éole Sylvain, graduate architect (Atelier TAG), Cédric Langevin, graduate architect (Atelier TAG), Nicolas Ranger, architect principal (JLP), Michel Bourassa, architect principal (JLP), Germain Paradis, technician (JLP), Olivier Millien, technician (JLP), Guylaine Beaudoin, technician (JLP), Serge Breton, specifications (JLP), Israel Ludena Cermeno, technician (JLP)

CLIENT / CLIENT

Nathalie Bondil, Director general and chief curator of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

CONSULTING TEAM / EXPERTS-CONSEILS ET AUTRES INTERVENANTS

Civil and Structural Engineer / Ingénierie civile et structurale : Jacques Chartrand et Guillaume Leroux, ing., Structure, NCK

Mecanical Engineers / Génie mécanique : Pierre Lévesque et Fabien Choisez, ing., Mécanique, SMi Énerpro

Builder / Constructeur : Robert Jacob, Pomerleau

Lighting Consultant / Consultant en éclairage : Conor Sampson, CS Design

Building Code Consultant / Consultant en code du bâtiment : Serge Arsenault, GLT+

Elevator / Ascenseurs : Pierre Grenier, Exim

Acoustic / Acousticien : Jean-Pierre Legault

3D visualization / Visualisation 3D : Doug & Wolf

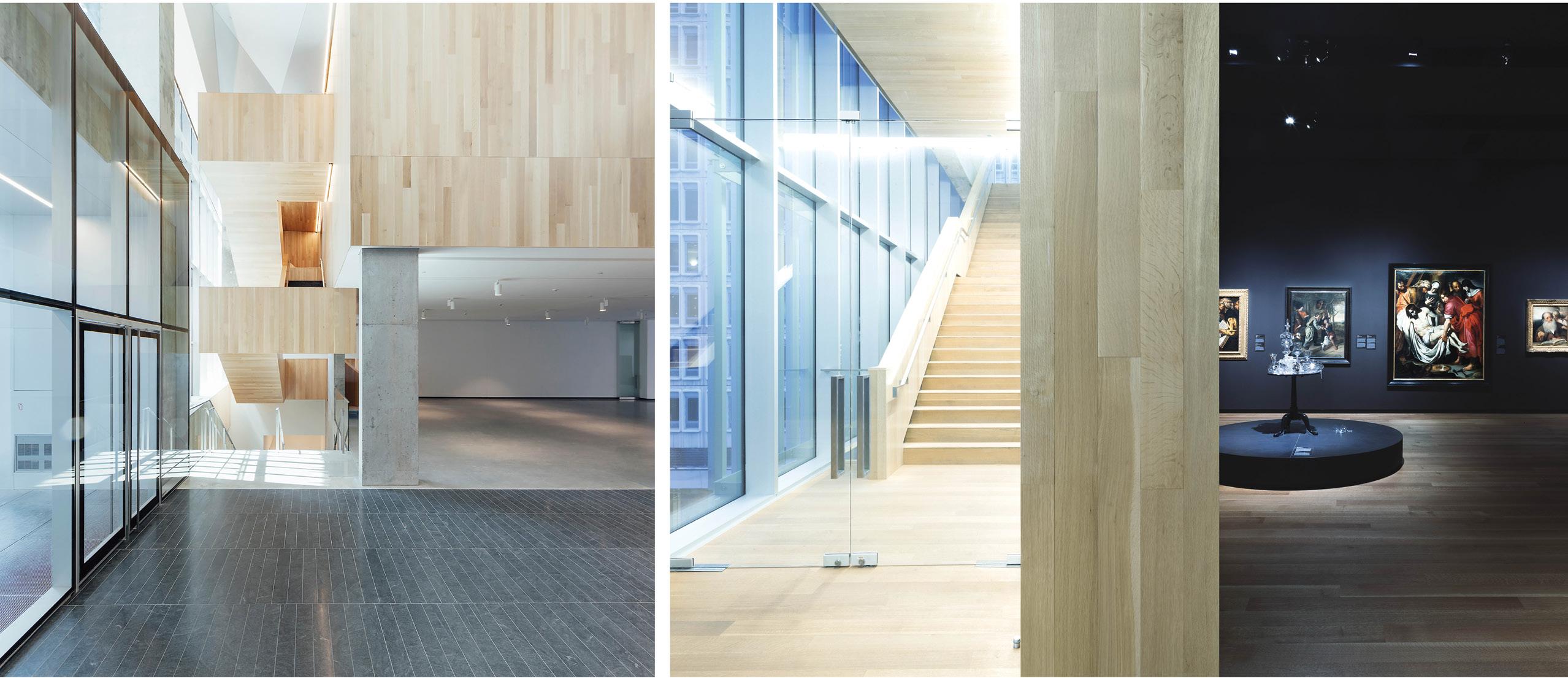

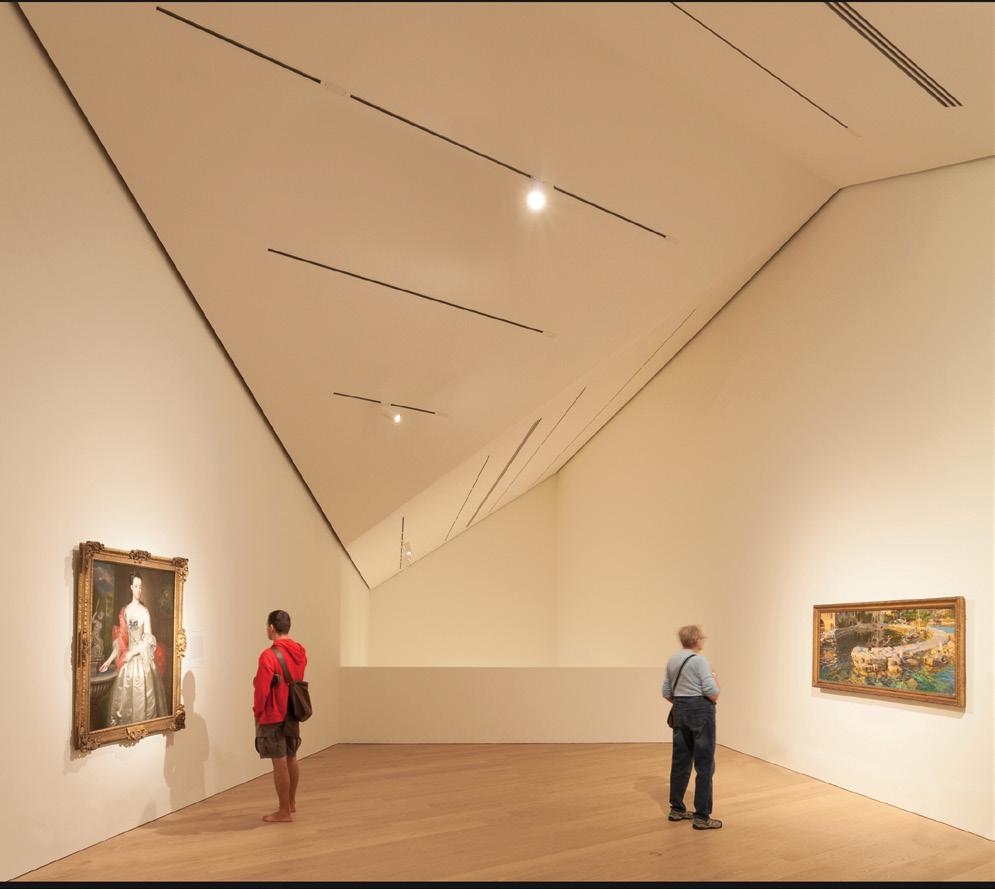

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) is composed of five pavilions: the Hornstein Pavilion (1910); the Stewart Pavilion (1976); the Desmarais Pavilion (1991); the Bourgie Pavilion (2011), and the new Pavilion for Peace (2016). The new building is located on Bishop Street to the south of the Desmarais Pavilion, designed by Moshe Safdie. The two buildings are linked by an aerial passageway spanning an alley. Whereas Sherbrooke Street has grown over the years to include larger-scale towers, Bishop Street has retained the 19th-century scale of Victorian houses. The project was conceived to address both of these scales simultaneously. The dynamic rotation of the bipartite composition allows a subtle integration of the Victorian scale. The rotation is geo-specific: the lower body turns and greets the visitor while the upper body opens toward the museum campus and Mount Royal further in the distance.

The MMFA campus is an assemblage of distinct architectural styles. Each pavilion evokes its era and provides a commentary on the particular role that the institution has played in society over time. This idea is foremost anchored in the unique circulation strategy of each pavilion. The Beaux-Arts museum of 1910, designed by architects Edward and William S. Maxwell, is structured around an introverted central grand stair that contributes little to the act of exhibition viewing. It is, “as though the ceremony of the visit was of equal importance to the contemplation of the artworks themselves 1”, whereas, the Pavilion for Peace redefines the institution’s relationship with the city, offering a renewed museum experience. Expanding upon the Bourdieusian theory

Le campus culturel du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal est un assemblage de bâtiments distincts qui présentent, d’un point vue architectural et programmatique, une certaine autonomie. Chaque extension du Musée évoque son époque et offre un commentaire sur le rôle que joue cette institution dans la société. Cette idée, exprimée à travers leurs factures architecturales, se révèle aussi comme étant profondément ancrée dans leurs concepts de circulation respectifs.

Ainsi, lors du tout premier concours en 1910, au moment où les musées demeurent des institutions fréquentées essentiellement par l’élite Montréalaise, les frères Maxwell proposent un musée de style Beaux-Arts organisé autour d’un escalier d’honneur central « dénué de toute utilité pour les expositions […] comme si la cérémonie de la visite égalait en importance la contemplation des œuvres ellesmêmes1.» Depuis la rue, le pavillon Maxwell demeure, comme il se voulait, hermétique.

En 1991, Moshe Safdie traduit l’idée d’un nouvel accès démocratisé et propose un musée post-moderne s’appuyant sur une approche typo-morphologique déclinant le patrimoine bâti immédiat. La ville pénètre le musée et participe à la vie du grand hall; elle occupe alors le centre tandis que l’escalier-rampe la borde et connecte visuellement et physiquement les différents niveaux.

Aujourd’hui, toujours impulsé par la critique « bourdieusienne » des années soixante, le musée poursuit cette idéologie d’accès à la culture légitime pour tous et développe son rôle social et sa dimension communicationnelle. À ce titre, nous proposons « le musée dans la ville ».

Ce concept spatial du « musée dans la ville » façonne la rencontre avec l’œuvre d’art et ses environs en offrant, à dessein, une expérience à la

of democratization of culture introduced by Safdie in his 1991 building, the Pavilion for Peace furthers the ideology of universal access to culture and continues to develop its social role and its communicative dimension. The proposed concept is structured around the event stair, addressing the expanded role of the 21st-century museum. This socio-spatial apparatus links the experience of the museum to the city and offers a multitude of spatial relationships. The in-between space, suspended in the city, animates the Bishop Street façade, providing visitors a momentary interlude from the contemplative experience of the galleries, and allowing them to reconnect with the city and the community beyond the walls of the MMFA. This interior urban promenade, fluid and filled with light, offers spectacular views of the mountain and the river. Through its event stair, the architecture of the pavilion positions the visitors, rather than the artifacts, at the center of the museum experience and activates bold, innovative programs associated with education and art-therapy. Its carefully choreographed architectural space facilitates social cohesion by encouraging impromptu public dialogue on art and a shared cultural experience.

The intimate scale of the Pavilion for Peace allows the MMFA to build upon this process of cultural democratization and to realize a museum that operates not as a sanctuary but as an accessible and engaged cultural agora.

fois plus intime et participative à travers la conception d’espaces inter-galeries qui proposent aux visiteurs une expérience culturelle partagée. L’architecture du Pavillon pour la paix côtoie ainsi les expositions et les programmes éducatifs et publics en tant que partie intégrante du programme muséal.

À l’ère de la post-neutralité scénographique des salles d’exposition se dégage, pour l’architecture du musée, une possibilité d’affecter la relation qu’entretien le public avec l’œuvre d’art. Au-delà de sa fonction d’écrin pour les collections, l’espace muséal participe à la médiation des œuvres pour les rendre plus accessible au grand public. Cette approche témoigne de l’intérêt porté à des formes d’expositions ou de musées qui ne sont plus seulement centrées sur les objets ou les savoirs, mais sur les visiteurs. De plus, l’échelle intime du nouveau pavillon permet d’élaborer ce processus de démocratisation culturelle et de réaliser un musée non pas comme sanctuaire, mais bel et bien en tant qu’agora de la culture accessible et engagée. Dédié au volet éducatif, il offre une opportunité de poursuivre le travail d’enracinement communautaire et identitaire amorcé au pavillon

Bourgie d’art Québécois et Canadien.

Dans cette optique, le concept proposé se traduit par la mise en place d’un dispositif socio-spatial, l’escalier-événement, qui se déploie en promenade architecturale informelle. Cet entre-deux, suspendu dans la ville, anime la façade de la rue Bishop et offre aux visiteurs une pause momentanée de l’expérience contemplative des galeries, leur permettant ainsi de renouer avec le contexte de la ville et de la communauté au-delà des murs du MBAM. Cet espace vertical relie l’expérience muséale à la ville et offre une grande variété de relations spatiales qui s’inspirent de l’idée de la rue et transfèrent cette expérience au musée.

The Pavilion for Peace beautifully and effectively fulfills its purpose of providing visitors with galleries, an all-in-one stairway, corridor, and linear public living room that winds its way up to the building. It works on both sides of its walls, providing a generous zone for gallery-goers within, while visually projecting its energy and activity to the city outside. The building is a sensitive insertion into the urban fabric, with a jogged façade that addresses the scale of the adjacent historic houses. The cool, abstract glass-and-aluminum palette of the exterior is balanced with the warm, natural wood of the interior. Its generosity of space and its strategic spatial zoning facilitates both efficient visitor movement and optional socialization. Visible from a block away and transforming into an illuminated lantern at night, the pavilion offers a transparent and welcoming transition from the gallery to the city.

Le Pavillon pour la paix atteint magnifiquement et efficacement son but en offrant aux visiteurs des galeries, un escalier tout-en-un, un corridor et des aires de détente linéaires qui mènent jusqu’à l’étage supérieur. Il agit sur deux plans en offrant une zone généreuse d’exposition de la collection et en projetant visuellement son énergie et son activité vers la ville à l’extérieur. Le bâtiment est une insertion sensible dans le tissu urbain. Sa façade tient compte de l’échelle des maisons historiques adjacentes. La palette froide et abstraite de verre et d’aluminium à l’extérieur est équilibrée par la chaleur du bois naturel à l’intérieur. La générosité des espaces et le zonage stratégique des espaces facilitent les déplacements des visiteurs et offrent des occasions de socialiser. Le Pavillon est visible de loin et le soir, il se transforme en une lanterne illuminée, offrant ainsi une transition transparente et accueillante entre le musée et la ville.

MAISON DE LA LITTÉRATURE

MAISON DE LA LITTÉRATURE

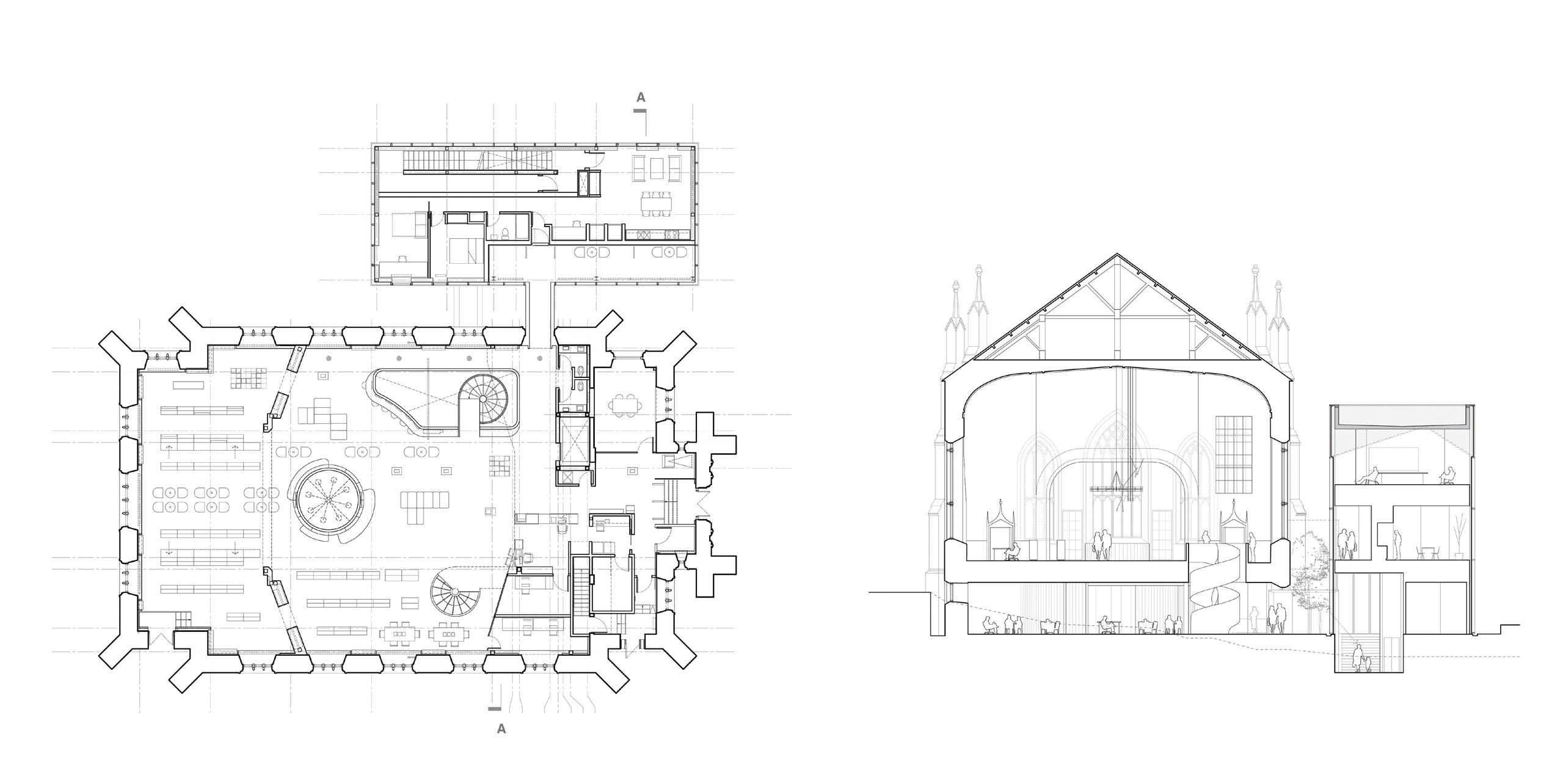

Given the significant programming requirements and the difficult and somewhat hidden access to the main spaces of Wesley Temple, the architects felt it was appropriate to move part of the program into a new annex outside the church space to create more walking areas and an increased sense of freedom. This strategy facilitated some of the work and provided a more effective layout for some of the spaces. It also helped declutter Wesley Temple, a heritage building, allowing the architects to preserve and restore the original spatiality of the overall structure.

The partly transparent and strangely familiar shape of this new annex gives an open, contemporary feel to the Institut Canadien de Québec, the main entrance of which is now accessed naturally from the bottom of the sloping Chaussée des Écossais where it intersects with Rue St-Stanislas. The institution’s interior layout provides greater access via the main door of the temple as well as the parking lot that also leads into the annex. These various access options all converge on the large opening in the floor and the hanging light fixture at the heart of the building, connecting the café, two exhibition areas, and the library collections.

This extension, which in its dialectic relationship with the original temple brings the institution fully into the 21st century with its e-books and Twitter poems, houses the main creative spaces in the upper levels. The idea of putting the creative spaces outside the temple while maintaining a close connection to it seemed symbolically appropriate. Slightly detached, its impressive views of the river and the old city offer a greater sense of freedom.

Étant donné l’importance des exigences programmatiques et l’accès difficile et peu évident aux espaces principaux du temple Wesley, il nous est apparu nécessaire, dans l’esprit d’offrir une multitude de parcours déambulatoires dégageant un fort sentiment de liberté, de déplacer une partie du programme dans une nouvelle annexe située en dehors des espaces du temple. Cette stratégie, en plus de faciliter certains travaux ainsi que l’aménagement plus efficace de certains espaces, aura permis entre autres choses de désencombrer le temple Wesley, un édifice patrimonial, et de nous assurer de conserver, voire même de restaurer, la spatialité originelle de l’ensemble.

En partie transparente et ayant des proportions étrangement familières, cette nouvelle annexe permet donc dans un premier temps d’offrir un visage ouvert et contemporain à l’Institut Canadien dont l’accès principal se fait maintenant de manière naturelle au bas de la pente de la chaussée des Écossais et dans l’axe de la rue St-Stanislas. À noter également que la disposition du programme à l’intérieur de l’institution permet de maintenir un grand nombre d’accès, notamment par la porte principale du temple ou encore par le stationnement à partir duquel on pénètre à nouveau dans l’annexe. Tous ces accès convergent par ailleurs vers la grande ouverture dans le plancher et le chandelier mobile, lesquels constituent le cœur de l’ensemble en reliant le bistro, les deux expositions et les collections.

Cet ajout qui, dans son rapport dialectique au temple d’origine fait entrer l’institution de plein pied dans le 21e siècle à l’ère des livres numériques et des

The insertion approach used for the new annex is aimed primarily at showcasing, complementing and preserving the heritage value of the existing building. The extension emerges as a strong symbol of the redeveloped heritage space and avoids altering the architectural composition of the existing structure. Placing the new program in the annex (originally planned for inside Wesley Temple) meant that no major changes had to be made to the existing stone envelope. The project also included a significant restoration component for the building’s masonry and English gothic church windows.

The glass annex establishes a material and formal dialogue with the existing stone building. The quality of its materials, its transparency, and simplicity of detail serve to reveal and showcase the existing structure. The extension’s simple and controlled skin does not compete with the richness and quality of the adjacent historic details and masonry assembly, creating a dialogue between the past and present of the historic neighbourhood of Old Quebec City.

poèmes sur Twitter abrite, dans ses étages supérieurs les principaux espaces voués à la création. D’un point de vue symbolique, l’idée de placer les espaces de création en dehors du temple tout en maintenant un rapport étroit avec celui-ci nous est apparue appropriée. En offrant une certaine distanciation, des vues imprenables sur le fleuve et la vielle ville, un sentiment plus grand de liberté en découle.

L’approche d’insertion préconisée pour la nouvelle annexe était principalement de mettre en valeur, de complémenter et de préserver la valeur patrimoniale de l’édifice existant. L’annexe se révèle comme le signal fort d’une importante remise en valeur patrimoniale et permet surtout d’éviter l’altération de la composition architecturale de l’édifice existant. Le nouveau programme localisé dans l’annexe (originalement prévu à l’intérieur du temple Wesley) évite les modifications importantes à l’enveloppe de pierre existante. Le projet propose un important volet de restauration de la maçonnerie et de la fenestration d’inspiration gothique anglaise de l’édifice.

L’annexe de verre établit un dialogue matériel et formel avec l’édifice de pierre existant. L’annexe, par la grande qualité de ses matériaux, sa transparence et sa simplicité de détail révèle et met en valeur l’édifice existant. La peau de l’annexe se veut résolument simple et bien contrôlée, elle ne rivalise pas avec la richesse et la grande qualité des détails et des assemblages de maçonnerie historique adjacents. Un dialogue entre l’histoire et le présent de l’arrondissement historique du Vieux-Québec se dévoile.

This transformation of and addition to a historic church into a literary cultural centre provides a complex spatial experience that engages with the past while imbuing the building with a new present-day relevance. By finishing everything uniformly in white, the structure of the historic architectural elements is brought forward. Against that structure, there is a play between the original and the new interventions. The plan of the new annex organizes the more cellular elements of the programme, freeing the space of the original church to be a more fluid interconnection of open spaces. The jury carefully deliberated over the radical approach taken to the historic church; the final structure evokes rather than restores the past. However, this re-invention offers a new spatial identity for an abandoned church.

Ce projet de transformation et d’ajout à une église historique pour en faire un centre de culture littéraire offre une expérience spatiale complexe qui engage dans le passé tout en imprégnant le bâtiment d’une nouvelle pertinence dans le contexte actuel. L’omniprésence du blanc dans tous les revêtements de finition met en valeur la structure des éléments architecturaux historiques. Il y a un certain jeu entre les interventions originales et les nouvelles. Le plan de l’ajout organise les éléments plus cellulaires du programme, libérant l’espace de l’église originale pour créer un lien plus fluide d’espaces ouverts. Le jury a délibéré avec soin sur l’approche radicale adoptée pour l’église historique; le résultat final évoque le passé plutôt que de le restaurer. Toutefois, cette réinvention offre une nouvelle identité spatiale à une église abandonnée.

/ PROJET

OCCUPATION DATE / DATE D’OCCUPATION

March 2014 / Mars 2014

BUDGET / BUDGET

$2.1 M / 2,1 M$

ARCHITECTS / ARCHITECTES

Lead Design Architects / Principaux architectes concepteurs : Pat Hanson, FRAIC

ARCHITECTURAL FIRM / CABINET D’ARCHITECTES

gh3

CLIENT / CLIENT

City of Edmonton

CONSULTING TEAM / EXPERTS-CONSEILS ET AUTRES INTERVENANTS

Architecture and Landscape Architecture / Architecture et aménagement paysager : Pat Hanson, Louise Clavin, Raymond Chow, Joel Di Giacomo, Byron White, Kamyar Rahimi, Simon Routh, Bryce Gracey

Structural / Structure : Chernenko Engineering (Diana Chernenko)

Mechanical / Mécanique : Vital Engineering (Iwona Vargas)

Electrical / Électrique : A.B. Electrical Engineering (Aaron Batty)

Construction / Construction : JenCol Construction (Douglas Sernecky)

Awarded through a national design competition in 2011, the Borden Park Pavilion attempts to recall the history of Borden Park through the reintroduction of the playful qualities of its status as an amusement park in the early 20th century.

The scheme makes overtly manifest the iconic geometry of classical parks and pavilions in its pedestrian design, comprised of axial and curving paths that merge into circuses at key points. This notion is further carried out by the circular form of the amenity pavilion itself, which also engages in a formal relationship with the park’s other geometric structures from past and present, such as the carousel, bandshell and Ferris wheel. Adjacent to the pavilion, a series of entry courts and seating patios emerge as soft and hardscaped rings – a trajectory of the building form into the landscape, as well as an expansion of its visual and useable footprint.

Primary functions of the amenity pavilion are confined to the core, allowing a complete 360-degree promenade around the building perimeter to maximize year-round engagement with the park and landscape through a fully transparent exterior skin. This skin, when viewed from the exterior in daylight, is visually impermeable and highly reflective. In mirroring the immediate landscape in striking triangular facets, the building seems almost to dissolve into its idyllic surroundings, lending a fleeting, ephemeral quality to the experience of the pavilion while encouraging a sense of liveliness and interactivity through the device of the façade as a fun-house mirror. Play, as a key conceptual driver of the project, draws on the park’s historic tradition as a popular Sunday at-

Réalisé à l’issue d’un concours de design national en 2011, le pavillon du parc Borden tente de rappeler l’histoire de ce parc en réintroduisant les qualités ludiques que lui conférait son statut de parc d’attractions au début du 20e siècle.

Le schéma illustre ouvertement la géométrie iconique des parcs et pavillons classiques dans son design piétonnier formé de voies axiales et de courbes qui convergent dans des ronds-points à des endroits clés. La forme circulaire du pavillon renforce cette notion et s’engage dans une relation formelle avec les autres structures géométriques du parc, anciennes et nouvelles, comme le carrousel, l’abri d’orchestre et la grande roue. Adjacents au pavillon, des cours d’entrée et des terrasses avec sièges émergent comme des anneaux souples et en matériaux inertes – une trajectoire de la forme du bâtiment dans le paysage et une expansion de son empreinte visuelle et utilisable.

Les fonctions principales du pavillon sont confinées en son centre, ce qui permet d’aménager une promenade à 360 degrés au pourtour du bâtiment pour optimiser pendant toute l’année le lien avec le parc et le paysage par une enveloppe extérieure entièrement transparente. Cette enveloppe, lorsqu’on la regarde de l’extérieur à la lumière du jour, est visuellement imperméable et grandement réfléchissante. En reflétant le paysage immédiat dans de remarquables pans triangulaires, le bâtiment semble presque se dissoudre dans son milieu idyllique, prêtant une qualité fugitive et éphémère à l’expérience du pavillon tout en favorisant une certaine animation et une interactivité par la ruse de la façade qui agit comme un miroir déformant. Le jeu, comme principal moteur conceptuel du projet, s’appuie sur la tradition historique du parc qui était un lieu de divertissement

BORDEN PARK PAVILION

PAVILLON DU PARC BORDEN

traction for thousands of residents who gathered to picnic, enjoy concerts and ballgames, and partake in rides on roller coasters and carousels. Fittingly, the pavilion’s form and expressive timber truss structure evoke the playful qualities of children’s toy drums and merry-go-rounds.

Material simplicity and structural uniqueness result in a building of studied minimalism. A distinct architecture is achieved through a seamlessly integrated building façade comprised of a glulam Douglas fir structural frame and an SSG (structural silicone glazed) curtain wall incorporating sealed glazed units. Both structure and cladding are triangulated and faceted, which allows the expression of the structural grid and pattern on the building’s exterior. The resulting floor-to-ceiling glazing provides captivating panoramic views from the pavilion while blurring the boundary between interior and exterior space and intensifying the sense of connection to seasonal dynamics and to the park itself.

An integrated approach to environmental sustainability is evident in the choice of materials: wood, concrete, and glass were selected for their durability, permanence, and timelessness. The structural ambition of the design emphasizes the use of rough whitewashed laminated timbers, whose rich patina and spatial arrangement recall the iconic structures and materiality of the park’s history while foregrounding the sustainable character of the pavilion. The building’s remaining palette consists of simple materials that, in character, emphasize the surrounding landscape, and in quality, ensure a robust and enduring building.

populaire le dimanche pour les résidents qui s’y rendaient pour pique-niquer, écouter un concert, jouer à la balle et faire des tours dans les montagnes russes et les carrousels. La forme du pavillon et sa structure expressive en bois d’œuvre évoquent avec pertinence les qualités ludiques des tambours et des manèges avec lesquels jouaient les enfants.

La simplicité des matériaux et l’originalité de la structure confèrent au bâtiment un caractère minimaliste étudié. L’architecture se distingue par une façade intégrée harmonieusement et faite d’un cadre structural en lamellé-collé de douglas vert et d’un mur rideau en vitrage silicone structural (VSS) qui intègre les unités vitrées scellées. La structure et le parement sont triangulés et à facettes, ce qui permet l’expression d’un réseau et d’un modèle structural sur l’extérieur du bâtiment. Le vitrage du plancher au plafond qui en résulte offre des vues panoramiques fascinantes à partir du pavillon tout en estompant la frontière entre l’espace intérieur et extérieur et en intensifiant l’impression d’être en lien avec la dynamique saisonnière et le parc.

Le choix des matériaux illustre avec éloquence l’approche intégrée à la durabilité de l’environnement : le bois, le béton et le verre ont été choisis pour leur durabilité, leur permanence et leur intemporalité. L’ambition structurale du design utilise le bois lamellé brut blanchi, dont la riche patine et l’organisation spatiale rappellent les structures iconiques et la matérialité de l’histoire du parc tout en mettant en valeur le caractère durable du pavillon. Les autres matériaux du bâtiment sont des matériaux simples qui mettent l’accent sur le paysage environnant et qui assurent la solidité et la permanence du bâtiment.

The pavilion gifts its community with a simple and joyous reductive architectural form. The integration of mullions and support framework, the triangular glazing units, and the circle-within-a-circle plan work together to generate a singularly powerful presence within a city park. It is the abstraction that would one would see at the level of art, but with which people can actually engage and play. Its character shifts diurnally, becoming nearly invisible at times as its mirrored facades reflect the surrounding trees, and then transforming into a lantern at sundown. It is a refreshingly well-considered and carefully designed object of fascination within what is the usually neglected programme of park infrastructure.

Le pavillon dote sa collectivité d’une forme architecturale simple et joyeuse. Les meneaux et l’ossature de soutien, les unités de vitrage triangulaires et la forme du cercle à l’intérieur d’un cercle s’unissent pour produire une présence singulièrement puissante dans un parc municipal. Œuvre abstraite que l’on pourrait considérer comme œuvre d’art, mais dans laquelle les gens peuvent réellement s’engager et s’amuser. Le jour, le pavillon devient presque invisible lorsque son enveloppe de miroirs reflète les arbres environnants, mais au coucher du soleil, il se transforme en une lanterne. Il est un objet de fascination bien pensé et soigneusement conçu dans le cadre d’un programme d’infrastructure pour un parc auquel on accorde généralement peu d’importance.

PROJECT / PROJET

OCCUPATION DATE / DATE D’OCCUPATION

September 2017 / Septembre 2017

BUDGET / BUDGET

$40 M / 40 M$

ARCHITECTS / ARCHITECTES

Lead Design Architects / Principaux architectes concepteurs : Siamak Hariri, Partner-In-Charge

ARCHITECTURAL FIRM / CABINET D’ARCHITECTES

Hariri Pontarini Architects

PROJECT TEAM / ÉQUIPE DE PROJET

Michael Boxer, Jeff Strauss, Edward Joseph, Howard Wong, Cara Kedzior, Rico Law, John Cook

CLIENT / CLIENT

Casey House

Joanne Simmons, Chief Executive Officer

CONSULTING TEAM / EXPERTS-CONSEILS ET AUTRES INTERVENANTS

Architects / Architectes : Hariri Pontarini Architects

Heritage Consultant / Consultants en conservation du patrimoine : ERA Architects

Structural Consultant / Consultants en ingénierie structurale : Entuitive

Mechanical Consultant / Consultants en mécanique : WSP Canada

Electrical Consultant / Consultants en électrique : WSP Canada

Landscape Architect / Architecte-paysagiste : Mark Hartley Landscape Architect Interiors / Design d’intérieur : Hariri Pontarini Architects

Code Consultant / Consultant en réglementation du bâtiment : David Hine Engineering

Acoustics / Acoustique : Swallow

Security / Sécurité : Mulvey & Banani

Food Service / Services alimentaires : Kaizen Foodservice Planning

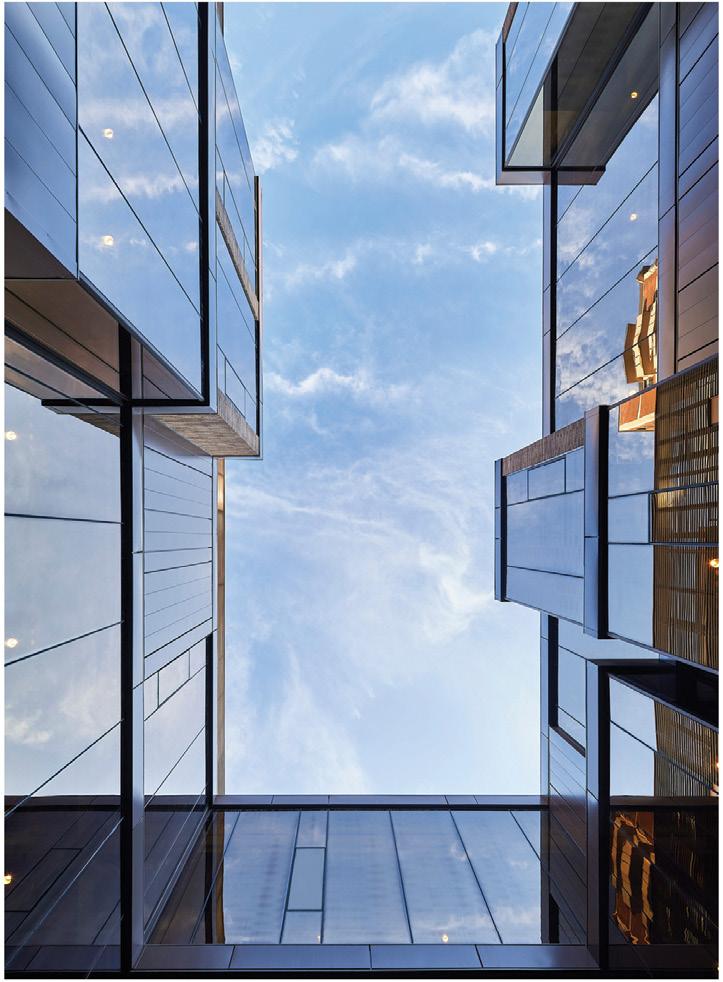

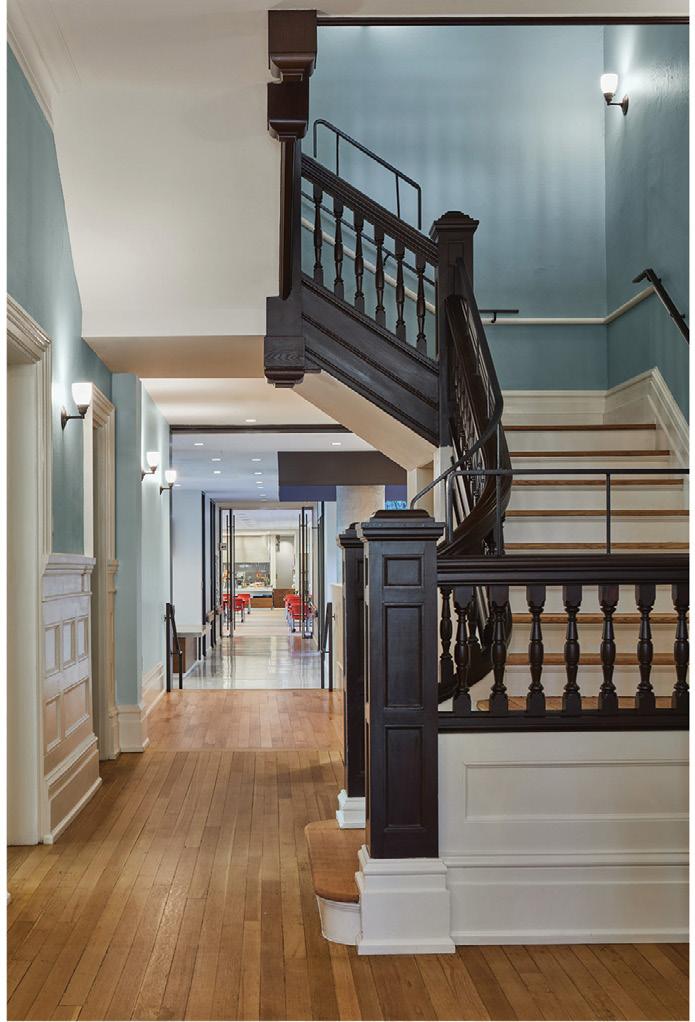

Ten years in the making, the renovation and extension of Casey House, a specialized healthcare facility for individuals with HIV/AIDS, develops a new prototype for hospitals. The facility meets the needs of patients and healthcare providers in a setting designed to evoke the experience and comforts of home. With 14 new inpatient rooms and new Day Health Program servicing a roster of 200 registered clients, the 5,481-square-metre addition brings much-needed space and modernized amenities to augment and renovate the heritage-designated Victorian mansion. The new structure embraces the existing building, preserving its qualities and organizing the day-to-day user experience around a landscaped courtyard.

An embrace emerged as a unifying theme to create a comfortable, home-like user experience, and an atmosphere of warmth, intimacy, comfort, privacy, connectivity, and solidity. Similarly, the language of the quilt, a symbolic expression of the battle against HIV/AIDS, was a source of inspiration for the design.

The architecture is a physical manifestation of the embrace in both the vertical and horizontal planes. The extension reaches over and around the restored Victorian mansion, while the new addition, with its robust, textured exterior, surrounds the central courtyard. Beautifully landscaped and alive, the courtyard is visible from every corridor and in-patient room.

As one of the original mansions built along Jarvis Street, the retention of the existing 1875 building (known colloquially as the “Grey Lady”) maintains the original character of the street, while the addition introduces a dignified juxtaposition of the old and new.

The façade, consisting of a palette of various

Échelonné sur dix ans, le projet de rénovation et d’agrandissement de la Maison Casey, un établissement de santé spécialisé pour les personnes atteintes du VIH/ SIDA, offre un nouveau prototype pour les hôpitaux. L’installation répond aux besoins des patients et des prestataires de soins dans un milieu conçu pour évoquer l’expérience et le confort d’un domicile. Le nouvel édifice d’une superficie de 5 481 mètres carrés comprend 14 nouveaux lits pour patients hospitalisés et héberge le nouveau programme de soins de jour qui offre des services à quelque 200 clients inscrits. L’ajout de ces espaces dont la Maison Casey avait grand besoin s’accompagne de la modernisation et de la rénovation de la maison patrimoniale de style victorien. La nouvelle structure englobe le bâtiment existant tout en préservant ses qualités et en organisant l’expérience quotidienne des utilisateurs autour d’une cour intérieure paysagée.

L’inclusion apparaît comme un thème unificateur pour créer un sentiment de confort semblable à celui que l’on éprouve à la maison et une ambiance de chaleur, d’intimité, de confort, de relations humaines et de solidité. De la même façon, le langage de la courtepointe, une expression symbolique de la lutte contre le VIH/ SIDA, a été une source d’inspiration pour le design.

L’architecture, tant dans son plan vertical qu’horizontal, est une manifestation physique de l’inclusion. L’agrandissement se déploie au-dessus et autour de la maison victorienne restaurée et le nouvel édifice, avec son extérieur robuste et texturé, entoure la cour intérieure centrale. Toutes les chambres et tous les corridors offrent une vue sur cette cour joliment aménagée.

La conservation de la maison originale de la rue Jarvis construite en 1875 (que l’on appelle familièrement la « Grey Lady ») maintient le caractère original de cette rue, alors que l’ajout apporte une juxtaposition raffinée de l’ancien et du nouveau.

brick, heavily tinted mirrored glass, and crust-faced limestone, is highly particularized and rich and becomes the architectural manifestation of the quilt. A garden in front, for delight and contemplation, is surrounded by a beech hedge for intimacy and privacy.

Once inside, the experience is about the engagement of the old and new and the organization, or the embrace, around the courtyard, which is the ever-present symbol of life-affirming green, water, and light (trees, fountain, and sunlight). Emphasizing the relationship between the old and new, the heritage building’s brick remains exposed in the Living Room. This central gathering space, featuring a two-storey atrium, is anchored by a full-height fireplace crafted from Algonquin Limestone. A bridge connects the heritage and new spaces on the second floor with long views stretching from end to end.

The courtyard allows direct sunlight into the core of the building on all floors. Given the private nature of the facility, it provides protected outdoor space for users, as well as transparency and clear sightlines across the project.

The design integrates sustainable features inherently related to the clients’ health and wellbeing. Green spaces, high-efficiency tinted glass, cross-ventilation via the courtyard and operable windows, bike racks, rainwater collection cisterns, and locally sourced and reclaimed materials also add to the sustainability profile of the project.

La façade, faite de diverses briques, de verre miroir de teinte foncée et de calcaire à surface rugueuse, est très détaillée et d’une palette de grande richesse. Elle devient la manifestation architecturale de la courtepointe. À l’avant, un jardin qui ravit et suscite la contemplation est entouré d’une haie de hêtres qui assure l’intimité.

La personne qui pénètre à l’intérieur du bâtiment ressent le dialogue entre l’ancien et le nouveau et l’organisation – elle éprouve un sentiment d’inclusion –autour de la cour intérieure qui est le symbole toujours présent de la verdure, de l’eau et de la lumière affirmant la vie (arbres, fontaines et lumière naturelle). Insistant sur la relation entre l’ancien et le nouveau, la brique du bâtiment patrimonial demeure apparente dans la salle de séjour. Ce lieu de rassemblement central, qui consiste en un atrium de deux étages, comprend un foyer pleine hauteur revêtu de pierre calcaire Algonquin. Un pont relie les espaces patrimoniaux aux nouveaux espaces au deuxième étage et offre des vues sur l’extérieur sur toute sa longueur.

La cour intérieure favorise la pénétration directe de la lumière du jour dans le cœur de bâtiment, à tous les étages. Vu le caractère privé de l’établissement, elle offre des espaces extérieurs protégés pour les utilisateurs tout en apportant de la transparence et des lignes visuelles dégagées dans tout le projet.

Le design intègre des éléments durables pour assurer la santé et le bien-être des clients. Les espaces verts, le verre teinté à haute efficacité, la ventilation croisée assurée par la cour intérieure et les fenêtres ouvrantes, les supports à bicyclettes, les citernes de collecte des eaux pluviales et les matériaux provenant de sources locales et de récupération ajoutent au caractère écologique du projet.

While carefully restoring the original century-old house, the expansion offers comfort, light and beauty to a population that has historically been underserved. The intimacy of the plan and the rich materiality turns the idea of a clinical environment on its head. The material palette is extensive and the discrete formal elements are many, but are handled with exceptional rigour and care, thereby transcending the ornate. The façade’s varied articulation and massing keep the new building in scale with the original building, as well as maintaining a harmonious ambiance and human scale for the workers, patients, residents and neighbours.

En plus de restaurer soigneusement la maison centenaire originale, l’agrandissement apporte du confort, de la lumière et de la beauté à une population qui a historiquement été mal desservie. L’intimité du plan et la riche matérialité réinventent la notion de milieu clinique. La palette de matériaux est vaste et les éléments formels discrets sont nombreux, tout en étant traités avec une rigueur et un soin exceptionnels, transcendant ainsi l’aspect ornemental. La diversité d’expression et de volumétrie de la façade maintient le nouveau bâtiment à l’échelle du bâtiment original tout en conservant une ambiance harmonieuse et une échelle humaine pour les travailleurs, les patients, les résidents et les voisins.

OCCUPATION DATE / DATE D’OCCUPATION

August 2011 / Août 2011

ARCHITECTS / ARCHITECTES

Lead Design Architect / Principal architecte concepteur :

Brian MacKay-Lyons

ARCHITECTURAL FIRM / CABINET D’ARCHITECTES

MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects

PROJECT TEAM / ÉQUIPE DE PROJET

Brian MacKay-Lyons, Talbot Sweetapple, Kevin Reid

David Bourque, Omar Gandhi, Sawa Rostkowska, Jordan Rice

CONSULTING TEAM / EXPERTS-CONSEILS ET AUTRES INTERVENANTS

Architects / Architectes : MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects Limited

Structural / Structure : Campbell Comeau Engineering Limited

Builder / Constructeur : Delmar Construction

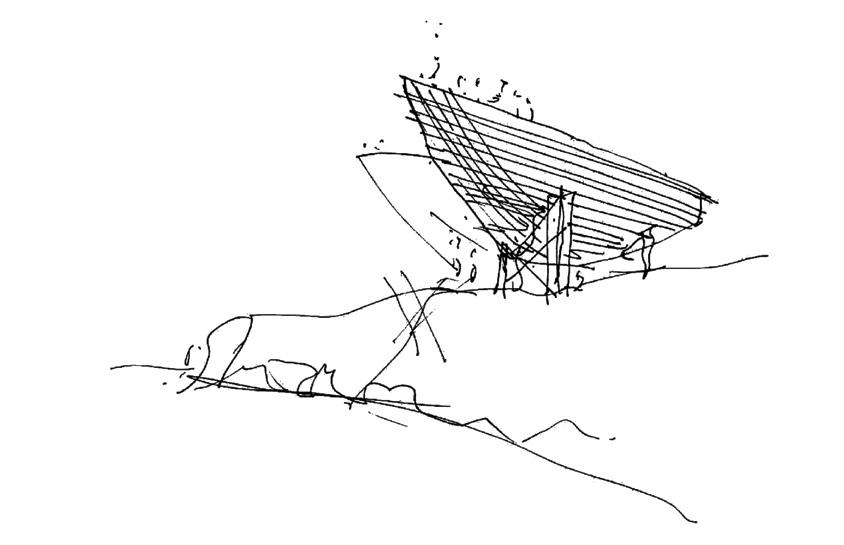

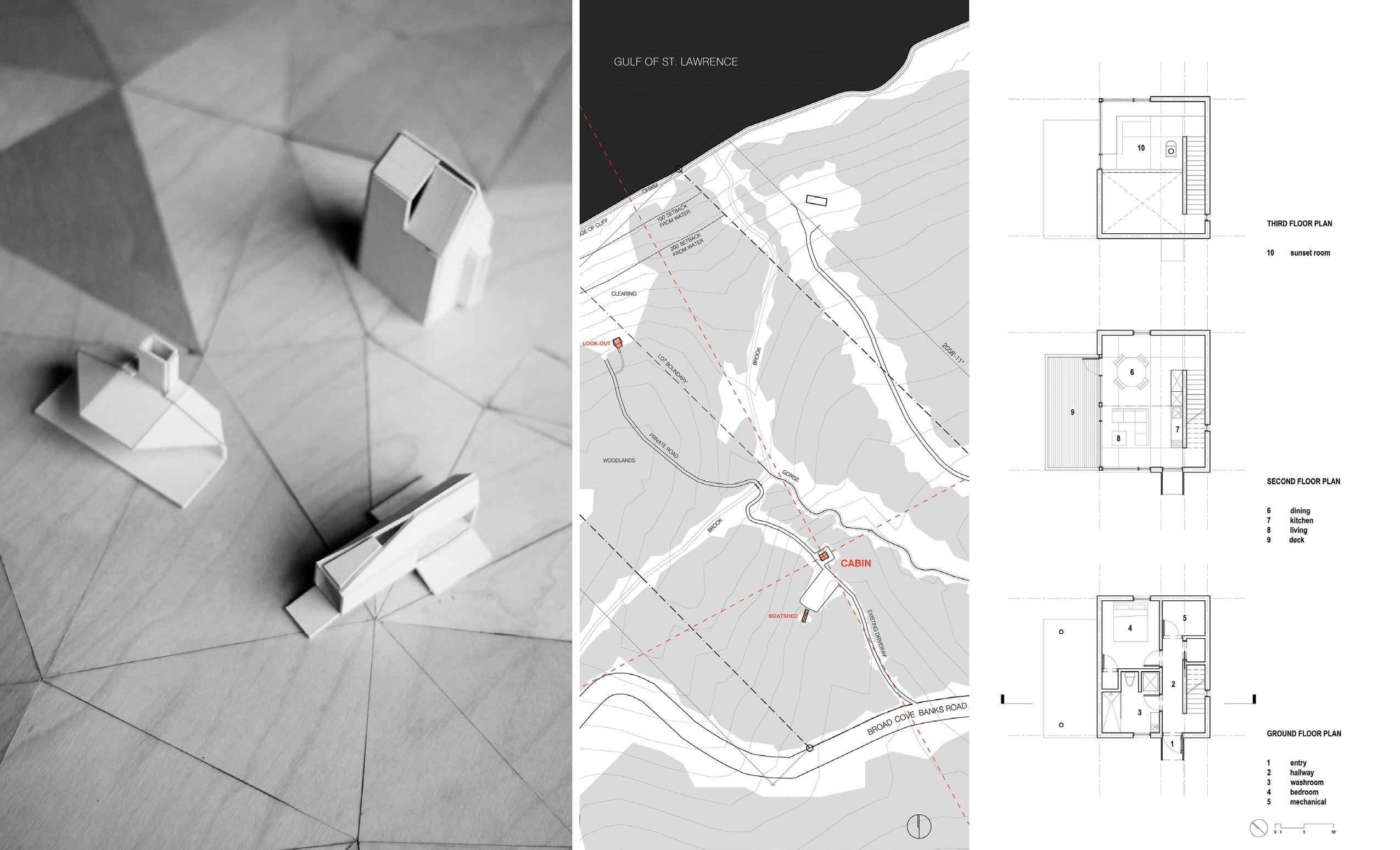

Two Hulls House is situated in a glaciated, coastal landscape with a cool maritime climate. The site’s geological make-up consists of granite bedrock and boulder till, creating pristine white-sand beaches and turquoise waters. Two pavilions float above the shoreline like two ship’s hulls resting on cradles for the winter, forming protected outdoor spaces between and underneath them. Like a pair of binoculars, Two Hulls House acts as a landscape-viewing instrument, effortlessly framing the environment. A concrete seawall on the foreshore protects the house from rogue waves. Two Hulls House touches the land lightly, resting on concrete fins, to have a minimal impact on the fragile land and flora.

This is a permanent home for a family of four, consisting of a day pavilion and a night pavilion. One approaches the understated, abstract public façade on the land side, then proceeds through the foyer, turning right to the sleeping pavilion or left into the living pavilion. Lantern-like outdoor porches dematerialize the two main forms on the ocean ends and glow from within at night. Inside the great room is a floating hearth 7.3-metres-long, the focal point of this space.

This is a steel-frame structure, comprising a bridge truss with a board-and-batten cedar skin. The white endoskeleton of Two Hulls House resists both gravity loads and wind uplift. The 9.8-metre cantilevers and the concrete fin foundations invite the ocean to pass under without damaging the hulls above. The fenestration of the “binocular” ends takes the form of minimalist curtain-wall glazing with structural silicone, while the side elevations contain

TWO HULLS HOUSE LA MAISON AUX DEUX COQUES

La maison aux deux coques est située dans un paysage glaciaire et côtier au climat maritime frais. La géologie du terrain se compose d’un substrat granitique et de till rocheux, ce qui crée des plages vierges de sable blanc et des eaux turquoise. Les deux pavillons flottent au-dessus du rivage comme deux coques de bateaux déposées sur leurs bers pour l’hiver, ce qui crée des espaces extérieurs protégés entre et sous les pavillons. La maison ressemble à des jumelles qui cadrent le paysage et permettent de l’observer aisément. Une digue de béton sur l’estran la protège contre les vagues scélérates. La maison touche légèrement le sol et repose sur des assises en béton pour exercer un impact minimal sur la terre et la flore fragiles.

Une famille de quatre personnes y habite en permanence. La maison comprend un pavillon de jour et un de nuit. On s’approche de la façade abstraite et discrète du côté terre, puis on pénètre dans le foyer où l’on peut tourner à droite vers le pavillon de nuit ou à gauche vers le pavillon de jour. Des porches extérieurs qui ressemblent à des lanternes dématérialisent les deux formes principales du côté de l’océan et brillent de l’intérieur pendant la nuit. À l’intérieur de la grande pièce, on trouve un foyer flottant de 7,3 mètres de longueur, le point central de cet espace.

La maison est faite d’une structure en acier, qui comprend un pont à treillis revêtu d’un parement en cèdre avec couvre-joints. L’endosquelette blanc résiste aux charges de gravité et au soulèvement sous l’action du vent. Les porte-à-faux de 9,8 mètres et les fondations de béton laissent passer l’océan audessous sans endommager les pavillons. La fenestration des extrémités des « jumelles » prend la forme d’un

storefront glazing. The geothermal heating system, with its concrete thermal-mass floors, harvests heat from the sun. This is a carefully crafted, durable building, that responds to its demanding climate to achieve a long life and elegantly reference the maritime heritage of its place.

mur rideau vitré avec silicone structural, alors que les élévations latérales comprennent des vitrines commerciales. Les planchers de béton chauffés par géothermie agissent comme des masses thermiques et absorbent la chaleur du soleil. C’est un bâtiment réalisé avec soin, qui est adapté à son climat rigoureux pour être durable et qui fait élégamment référence au patrimoine maritime du lieu.

Drawing vernacular references into a form evocative of two bridges cantilevered over the water, the Two Hull House generates a dramatic presence on the landscape. In abstracting the forms of the ships that once helped build up the region, the architect has infused the house with an intriguing ghost-like quality and a strong sense of place. Inside, the architecture and ocean are in dialogue, with a fenestration pattern that offers a variety of views that are distinctively different from the generic linear ocean views of most waterfront houses. The hooded decks give a sense of comfort and shelter in a harsh climate, even as they literally bring the inhabitants closer to the ocean.

Exprimant les références vernaculaires dans une forme qui évoque deux ponts en porte-à-faux au-dessus de l’eau, la résidence Two Hulls apporte une présence spectaculaire dans le paysage. En s’appropriant la forme des bateaux qui ont autrefois aidé à bâtir la région, l’architecte a donné à la maison un caractère intrigant qui la fait ressembler à une apparition fantomatique tout en lui donnant un sens du lieu prononcé. À l’intérieur, l’architecture noue un dialogue avec l’océan et l’agencement des fenêtres offre divers points de vue bien différents de la vue linéaire sur l’océan qu’offrent la plupart des maisons en bord de mer. Les terrasses en bois procurent un abri et un sentiment de confort dans un climat rigoureux, même si elles rapprochent littéralement les habitants de l’océan.

PROJECT / PROJET

OCCUPATION DATE / DATE D’OCCUPATION

June 2014 / Juin 2014

BUDGET / BUDGET

$88 M / 88 M$

ARCHITECTS / ARCHITECTES

Lead Design Team of Architects / Principaux architectes concepteurs :

Steve McFarlane, Michelle Biggar, Rob Grant, Beth Denny, Nicholas Standeven

ARCHITECTURAL FIRM / CABINET D’ARCHITECTES

office of mcfarlane biggar architects + designers inc. (omb)

Project commenced as predecessor firm mcfarlane green biggar Architecture + Design Inc.

PROJECT TEAM / ÉQUIPE DE PROJET

Steve McFarlane, Michelle Biggar, Rob Grant, Beth Denny, Nicholas Standeven, Jennell Hagardt, Adam Jennings, Kevin Kong, Heather Maxwell, Hozumi Nakai, Lydia Robinson, Jing Xu, Jordan VanDijk, Mingyuk Chen, Justin Bennet, Seng Tsoi, Simon Clewes, Adrienne Gibbs

CLIENT / CLIENT

Fort McMurray Airport Authority

CONSULTING TEAM / EXPERTS-CONSEILS ET AUTRES INTERVENANTS

Prime Consultant + Architect / Principaux consultants + architectes : office of mcfarlane biggar architects + designers inc. (omb). Project commenced as predecessor firm mcfarlane green biggar Architecture + Design Inc.

Structural / Structure : Equilibrium Consulting Inc.

Mechanical / Mécanique : Integral Group

Electrical / Électrique : Integral Group

Landscape / Aménagement paysager : PWL Partnership

Interiors / Design d’intérieur : office of mcfarlane biggar architects + designers inc. (omb).

Project commenced as predecessor firm mcfarlane green biggar Architecture + Design Inc.

Specialist Consultants: IT + Security / Consultants spécialisés: TI + Sécurité : Faith Group LLC

Wayfinding + Signage / Orientation + signalisation : The Design Office

Code / Code : GHL Consultants Ltd.

Vertical Transportation / Transport vertical : JW Gunn Consultants Inc.

Lighting / Éclairage : Total Lighting Solutions

Acoustics / Acoustique : BKL Consultants

Specifications / Spécifications : Morris Specification s

Builder / Constructeur : Ledcor Construction Ltd.

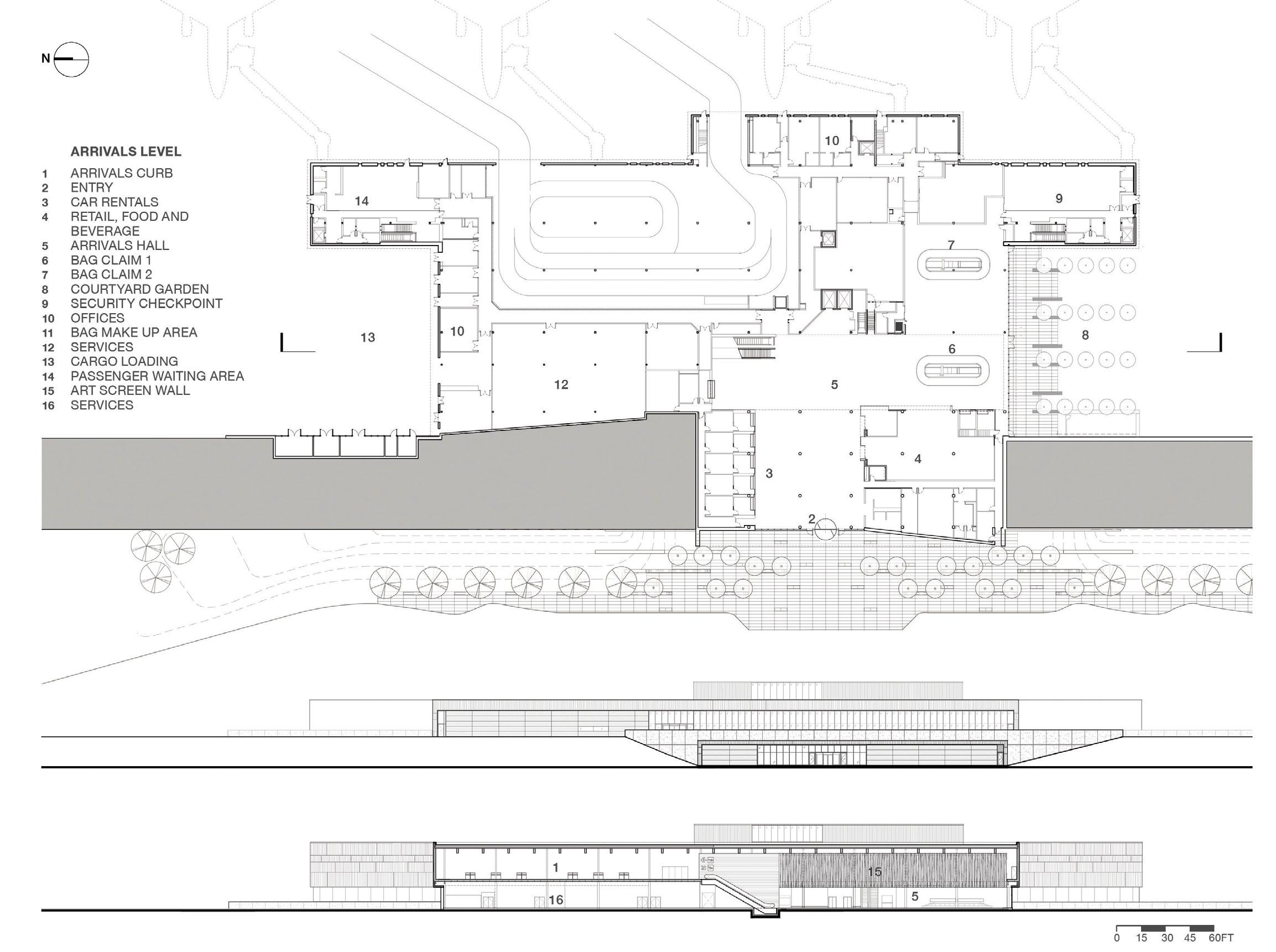

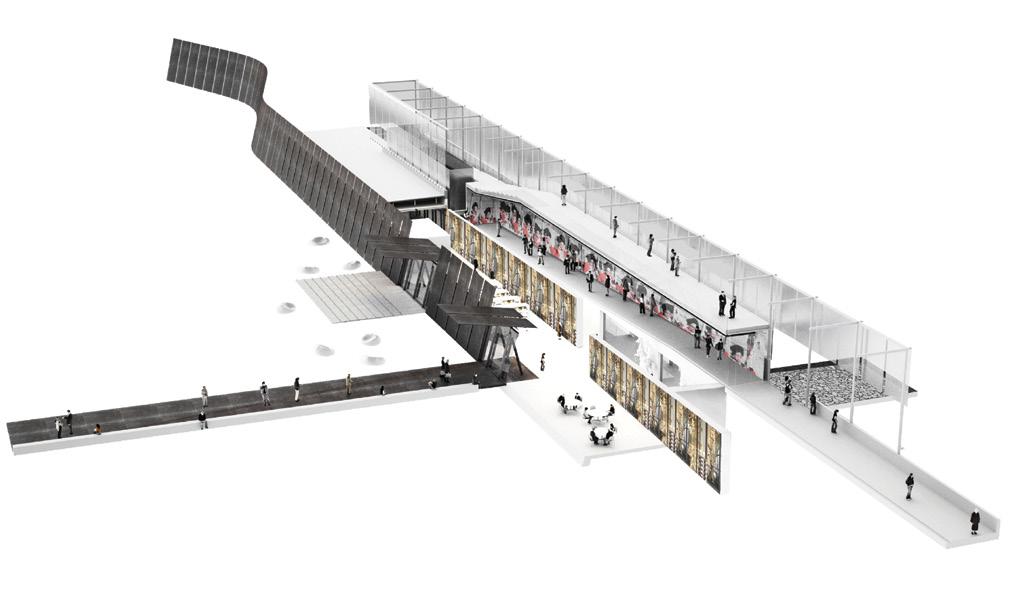

The new Fort McMurray International Airport Terminal creates a meaningful portal for the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo in the northern reaches of Alberta; a region characterized by its spectacular geography and the natural beauty of the boreal forest, the prairies, and the northern lights. Host to the national oil sands industry, the small community of Fort McMurray has been thrust onto the global stage, stimulating unprecedented growth and cultural diversification.