18

New beginnings feature

Scholarship supports new renal transplant program for patients with high BMIs The Pickard Robotic Training Scholarship has enabled Mr Shantanu Bhattacharjya to reach the final stages of developing a robotic renal transplant program in South Australia for patients with a high body mass index. Patients with a high body mass index (BMI) are unlikely to make it to the kidney transplant waiting list because a BMI higher than 35 makes the transplant technically difficult and the outcome less than optimal. Of particular concern are the number of Indigenous patients who need to stay on dialysis indefinitely because being overweight excludes them from the waiting list. Mr Bhattacharjya’s concern isn’t singular. As well as these patients missing out on kidney transplants, he worries about the cost of ongoing dialysis to the taxpayer. It can cost around $85,000 annually for dialysis in an urban setting and up to $124,000 in a remote setting. Annual home haemodialysis costs about $43,000.1 While the cost of dialysis is about the same as a transplant in the first year, in the second and subsequent years it is substantially less.

“A transplanted patient is a huge cost saving to the taxpayer.” Referring to a 10-year study by the University of Illinois at Chicago, published in 2019, Mr Bhattacharjya said the study has demonstrated that robotic surgery can be used successfully for kidney transplants on recipients with median BMIs up to 41. The study reported “one- and three-year patient survival rates of 98 per cent and 95 per cent, respectively, among patients with obesity”. Out of 239 recipients, only 17 developed graft failures and went back to dialysis, “resulting in 93 per cent three-year kidney graft survival”.2 When compared to a national United States database, these results were similar to those seen in non-obese patients across the same period (2009-2018). Mr Bhattacharjya completed his General Surgery training in India, then higher surgical training in the Oxford training scheme in the United Kingdom (UK) with

Fellowships in hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery and transplantation. He performed the first live donor simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant in India in 2008, then worked as a consultant in the UK for seven years. After immigrating to Australia in 2016, he set up a steroid-free whole organ pancreas transplant program that’s had 100 per cent patient and graft survival rates since its inception. More recently, Mr Bhattacharjya completed his training in robotic surgery. For his research on robotic kidney transplants, Mr Bhattacharjya and his team developed a large animal model of heterotopic kidney auto-transplantation, similar to the procedure performed in humans. “We did four cases of robotic and four cases of laparoscopic kidney transplant surgery,” to ascertain which technique was more robust and easier. Now, after developing the model, performing the transplants, observing the outcomes, and being trained in robotic surgery, “we’re almost in the position of offering it as a clinical program,” he said. For a robotic kidney transplant program to be truly effective, its design has to cater for deceased donor transplantation, an unpredictable service, rather than a living donor program that is more planned and predictable. This means robotic transplants would likely be provided out of the Royal Adelaide Hospital – the only quaternary hospital in South Australia that offers transplantation. Mr Bhattacharjya consults there, although other options, such as public–private partnerships, are being explored. He is hoping the hospital will be able to procure a da Vinci Xi robotic surgical system, which is the new generation robotic system optimised for complex surgery with minimally invasive surgical options. “There’s a learning curve associated with any new program,” Mr Bhattacharjya said. “At first you take a standard risk and as the team experience and confidence grows you move on to more complicated cases – in

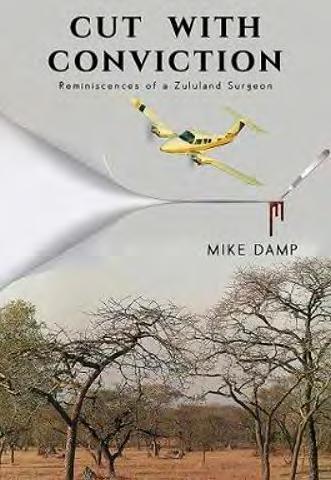

Dr Shantanu Bhattacharjya

this case transplant recipients with higher BMIs.” Robotic surgery provides the combination of three-dimensional vision and the flexibility of being able to rotate your instruments inside, Mr Bhattacharjya explained. “It’s the seven degrees of freedom that you get with instrumentation. If you’re doing laparoscopic surgery, you’re actually operating in two straight lines; whereas, robotic surgery is more natural – almost like operating inside the patient.” Mr Bhattacharjya said he is grateful to the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons and the Pickard Robotic Training Scholarship for supporting his research and reaching the final stages of the robotic renal transplant program. The program, aimed at Indigenous people with increased comorbidities including obesity, will enable them to live normal lives and engage more readily in exercise and weight loss. REFERENCES 1. Gorham G, Howard K & Zhao Y et al. 25 June 2019. Cost of dialysis therapies in rural and remote Australia – a micro-costing analysis. BMC Nephrology, Spring Nature. Retrieved from https://bmcnephrol. biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12882-019-1421-z. 2. University of Illinois at Chicago News Release 19 Nov 2019. Robotic transplants safe for kidney disease patients with obesity. Retrieved from https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2019-11/ uoia-rts111919.php.