3 minute read

Then Now

1918 Pandemic in Philadelphia

As the coronavirus pandemic ravages a global community, the Crier looks back at the Spanish Flu pandemic that ravaged Philadelphia in particular.

By Terry Buckalew

The Liberty Loan Parade, held on September 28, 1918, was organized to promote the government bonds issued to help pay for World War I. With more

than 200,000 Philadelphians in attendance, it led to one of the country’s largest outbreaks of the 1918 flu.

The morning of September 28, 1918, was cool and clear. It was a beautiful day to have a War Bond rally and a parade in the city of Philadelphia. World War I was raging in Europe, and citizens needed to show their patriotism by supporting the troops. Tragically several weeks later, the families of 15,000 dead Philadelphians would mark this day with dread.

There were only 47 cases of Influenza (“Spanish Flu”) reported in the city by this time. However, there were 600 stricken men in the Philadelphia Naval Base Hospital. City and military officials were congratulating themselves, believing that they had curtailed the spread. But the city’s health director, Dr. Wilmer Krusen,

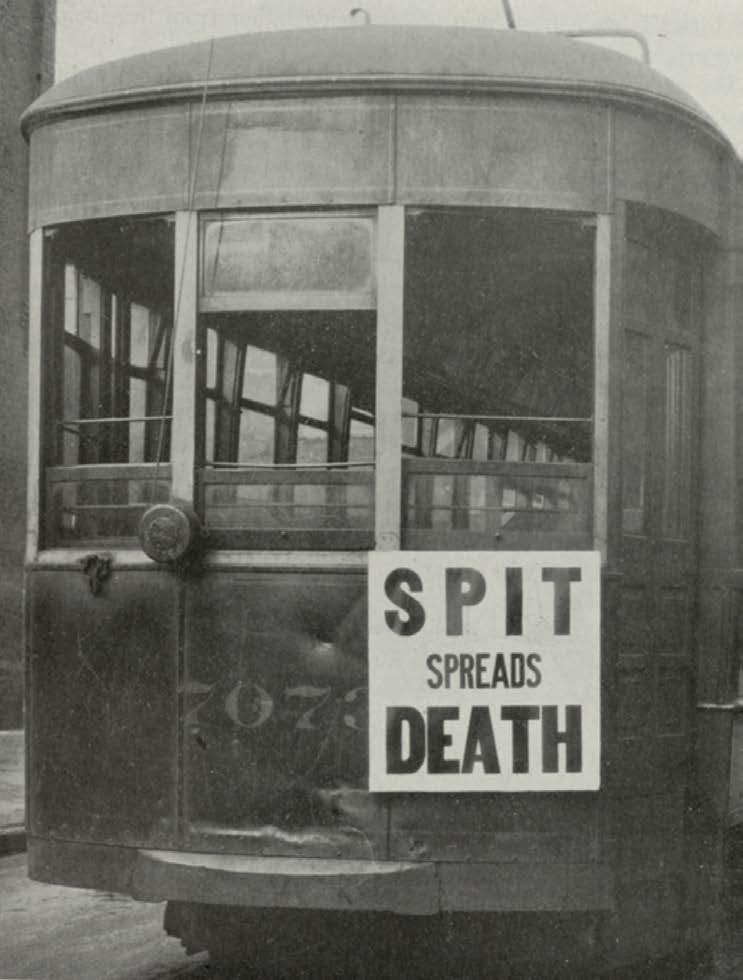

A Philadelphia tram offers timely advice, c. 1918.

knew differently. Starting in August, a viral wave crashed down on the East Coast, killing thousands and overflowing hospitals, military and civilian, with the seriously ill. Dr. Krusen knew it was just a matter of time but foolishly hoped he had one more day of grace.

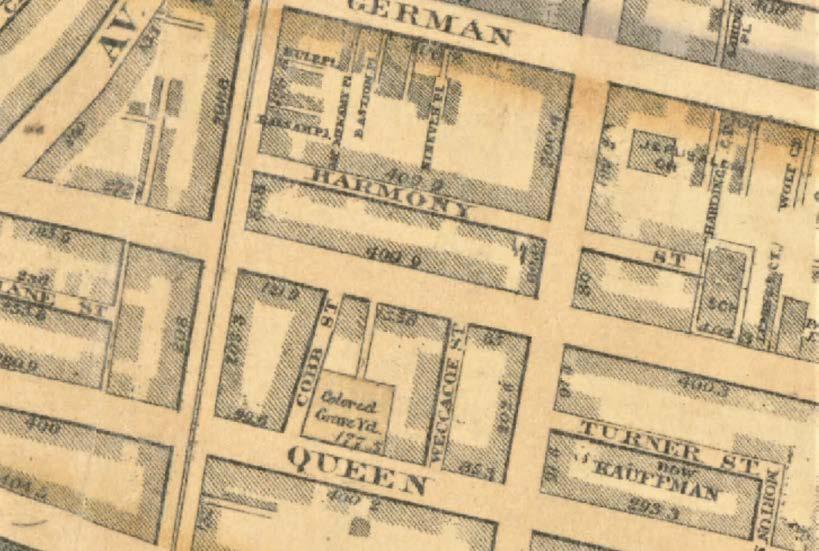

The disease took an exceptional toll on Southwark residents. The southeast neighborhood was overcrowded with Italian, Russian, and Russian Jewish immigrants packed into ramshackle tenements. Add to this, the influx of 500 African Americans a week, escaping the Jim Crow Southern states, and it made for a perfect breeding ground for a plague.

Warnings came from numerous sources about the danger that the parade could pose to the city. However, the very powerful industrial leaders in the city, who controlled the Mayor and City Council, were against it. They had invested a lot of money in the floats advertising their companies. It also had become a contest among the business owners to see who could create the best floats accompanied by the largest number of their employees. Starting at noon on the 28th, more than 200,000 cheering and singing men, women, and children lined South Broad Street for 23 blocks. The crowd roared as 2,400 sailors and Marines from the Naval Base passed by, led by the Marine Band from the same base. They were followed by 10,000 marchers. The next day newspapers proclaimed the parade the best the city had ever seen. The same newspapers also mentioned Dr. Krusen’s justreleased statement that citizens should avoid crowds if possible.

Three days after the parade the city experienced a viral “explosion of great force.” On October 4, Dr. Krusen ordered the closure of all schools, churches, restaurants, and saloons. All 31 city hospitals were quickly overrun. A call went out for volunteer gravediggers to help bury the corpses that had piled up outside the morgues and cemeteries. In the end, Philadelphia had the highest death rate in the county. Almost 10 percent of the 150,000 who caught the disease died. It was a devastating loss to the population and the fabric of the city. ■

To learn more, visit the exhibit “Spit Spreads Death: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19 in Philadelphia” at the Mütter Museum (in person or virtually) at muttermuseum.org/ exhibitions/going-viral-behind-the-scenesat-a-medical-museum/.

For a really deep dive into the story of the 1918 pandemic, see John M. Barry’s The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.