10 minute read

Killing the Crosstown

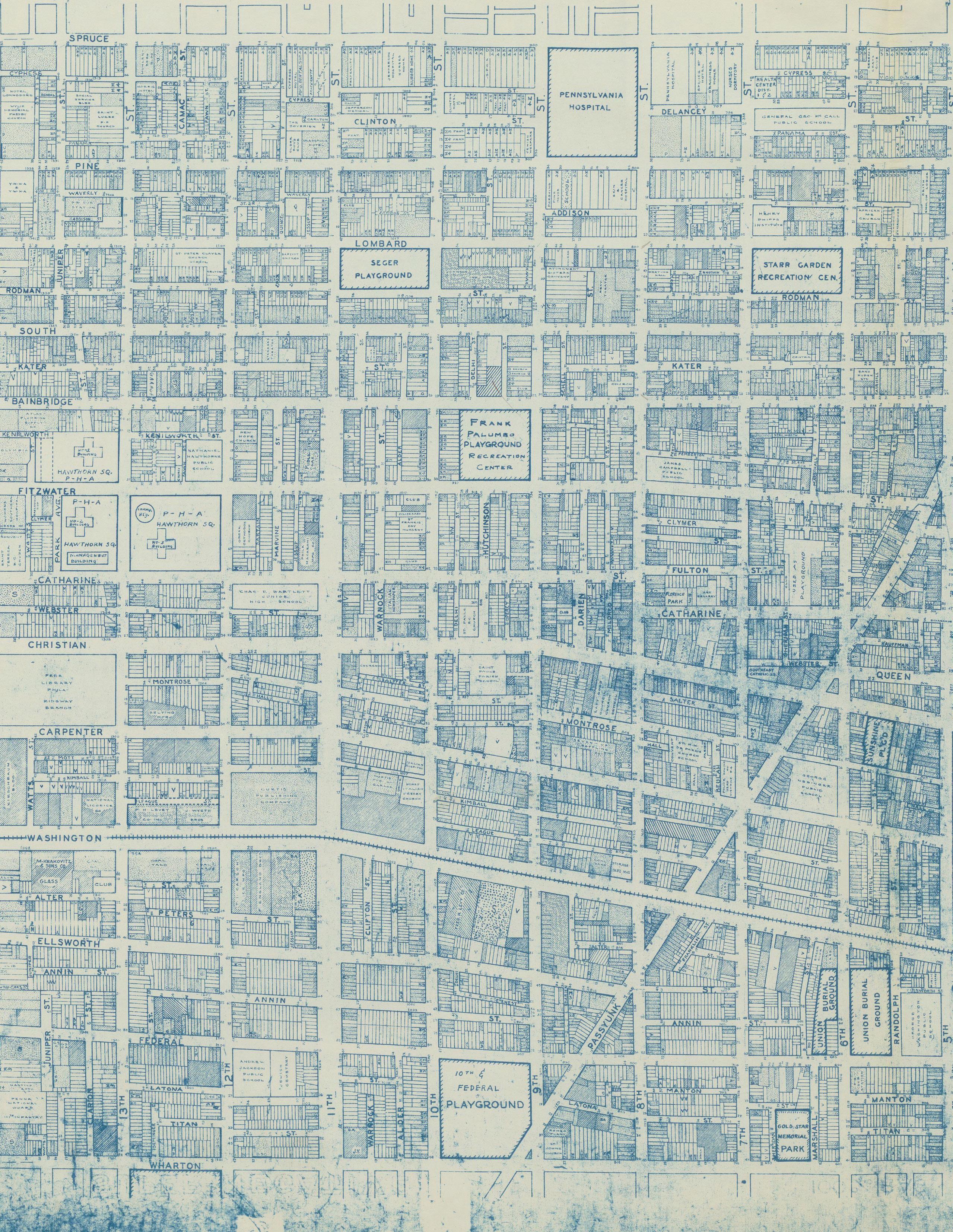

This 1962 land use map shows us what Queen Village looked like before the Front Street corridor was demolished.

1 B'nai Reuben Synagogue 2 The Yiddish Theatre 3 Kesher Israel Synagogue 4 Abbotts Dairies 5 Historical Community Settlement Playground 6 South Street Ferry Terminal 7 Spalding Tenament House 8 Ahavas Israel Synagogue 9 Southern Dispensary 10 Kahillis Israel-Nusach Sfard Synagogue 11 William Meredith School 12 B'nai Israel-Anshe Poland Synagogue 13 St. Stanislaus Church and School 14 Polish Social Club 15 Church 16 Kahal Adath Jeshurun Synagogue 17 Neziner Synagogue 18 Sunshine Playground 19 Weccacoe Playground 20 Central Hebrew School and Literature Society 21 Queen Park 22 Philadelphia Fire Department 23 Neighborhood Boy's Club 24 George Nebinger School 25 Settlement Music School 26 Henry Burk School 27 St. Philip Neri Church and Rectory 28 Adath Israel Synagogue 29 St. Philip Neri School and Convent 30 Shot Tower Playground 31 Polish Bethel Church 32 Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') Church 33 Hector McIntosh Playground 34 Emanuel German Evangelical 35 Lutheran Church Nazareth Church 36 Mariners' Bethel Church

BY JIM MURPHY

This was the planned route of the Crosstown Expressway. 6

How a mix of community groups with different agendas stopped a hated highway

Below are excerpts from a 75-minute community program that took place Oct. 19 at Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') Church Sanctuary.

The topic: How a diverse group of activists from both sides of Broad Street kept the South Street area from being destroyed by the Crosstown Expressway in the late '60s and early '70s. The eight-lane road was due to run river to river. Fortunately, local protestors won the battle. But it was not easy.

The meeting was co-sponsored by Queen Village Neighbors Association (QVNA) and the Historic Gloria Dei Preservation Corporation (HGDPC).

OUR PANEL …

• Paul Levy, master of ceremonies for the evening; also founding CEO of the extremely successful Center City District and author of “Queen Village: The Eclipse of a Community.”

• Marge Schernecke, a community organizer and leader in Queen Village whose family has lived in the area for five generations.

• David Auspitz, former owner of Famous Fourth Street Delicatessen and Famous Fourth Street Cookie Company, and former chairman of the Philadelphia Zoning Board.

• Rick Snyderman, co-founder of The Works Gallery, and a key player in organizing the “South Street Renaissance.”

• John Coates, former housing development leader and executive director of SCPACC, or South Central Project Area Community Corporation, a river-to-river coalition of community groups.

• Ed Williams, a community activist and member of the Southwest Center City Citizens Council.

• Conrad Weiler, former national activist preventing displacement in gentrifying neighborhoods, QVNA leader and Temple University political science faculty member since 1968.

• Joel Spivak, architect, artist, former owner of Rocketships & Accessories and originator of Philadelphia’s National Hot Dog Month Celebration.

Crosstown Expressway protesters parade around City Hall. Mrs. Joreatha Lindsey and her three-year-old daughter, Vivian, of South Philadelphia, lead the marchers.

Photo Credit: Temple University Libraries, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin collection.

OUR PROGRAM … A highway that did not happen Paul Levy introduced the meeting, reviewed Philadelphia's manufacturing history and discussed city plans for the Crosstown Expressway. He also used 87 PowerPoint slides to help tell his story. "Before we had a casino (SugarHouse), we actually refined real sugar at the Jack Frost site." I-95 "separated the city from the central waterfront in very major ways. So we have this gigantic gap we know only giants can cross over. (He showed the giant Stickmen from the South Street Pedestrian Bridge and got a big laugh from the crowd.) "It was the age where we thought people would only move around by cars. So it was a huge commitment to building highways. And all right of way was achieved by condemnation." "The story really begins with the fact that a group of people finally said, "'We're not just going to roll over and play dead.' " "People were starting to say, 'Preserving neighborhoods is more important than enhancing mobility.' That was the key message to all of this."

"What was most important about this at a time in the history of this city where black and white neighborhoods did not actually get along very well, this was a bi-racial coalition." "South Street today … river to river it is a thriving commercial corridor." "We went back and looked at the assessed value of all the real estate in the red area, which is the corridor that was going to be demolished for the Crosstown Expressway. "And the real estate tax paid in that corridor in 1972, the year the highway was stricken, was $353,000 a year. This next year the tax bill due in that corridor is $17 million. "If you ever want to know what happens if you don't build a highway, it (the difference) represents $285 million dollars in real estate taxes collected from an area where the highway was not built." "And what we call center city or greater center city … Girard to Tasker, River to River, is now the fastest growing residential section of the city. We're up to about 188,000 people, grown by 99% and 25% of all people who moved into center city in the last five years moved into just the downtown."

PennDOT's letters were unclear and scary to recipients.

The upside is there is no highway

John Coates discussed struggles to keep the coalition together.

"What we had then was roughly 43,000 area residents of diverse political, social, and economic values."

"I must say this is one of my more friendly nights in Queen Village. (Laughter. Paul Levy quipped: "It just got started though.")

"I always liked coming to Queen Village on Monday nights, because meetings got over early because of Monday Night Football."

"The takeaway here is you had groups that had many many different types of agendas, and while I juggled between all of them to try to keep the coalition together, the upside is there is no highway, development has happened, and here we are tonight to celebrate."

"We thought it was a trick for black folks." Ed Williams said the black community didn't really believe a road was coming through. "Our area south of Washington Avenue didn't identify with Rittenhouse Square. So we changed the name to SWCCCC: Southwest Center City Citizens Council or SWCCCC." "One of the things … that actually pulled our people together was because they did not believe there actually was going to be an expressway. They thought it was another trick. "In the black community at that time, every time so called white folks come up with an idea, it was some kind of trick for black folks. So we had a hard time trying to keep it together, saying 'Yes, it is true, the highway is coming through.' "

We had one goal

Marge Schernecke described diverse groups with a single focus. "One thing I want to stress. This community was diverse ethnically, racially, religiously. And what we had in common I think with all the other groups in the South Central Pac was one goal: Get rid of this highway. Nobody had a secret agenda or ulterior motive. "There were people that lived on South Street in those days in favor of the highway. We weren't. We had already lived with 130 houses being taken from us that were historically certified for I-95. We didn't want another highway."

The bond was about tolerance

Rick Snyderman spoke about the South Street culture.

"A group of people came here because South Street was largely abandoned in the 1960s, and they were people who were from everywhere, so they were not an ethnic community. They were not a tight group of people that shared some kind of particular heritage or background. They were people who shared something else, which was an interest in creative energy." "The South Street community began as a group of people that came from elsewhere and their approach was completely opposite. Their bond was about tolerance." "Before there was an acceptance of gays in Philadelphia, there was South Street. … South Street was a theater piece. And not surprisingly, it was because it began in 1965 with a repertory company of people from all over the country that started the Theater of the Living Arts. That included people like Morgan Freeman, and Danny DiVito and Sally Kirkland, who all began their careers on the 300 block of South Street. " "We were theatre people. We were actors on the stage of the city of Philadelphia. We would stage parades and protests. And thousands of people would come to South Street. And we would then argue to the city officials and the state officials, how can you tear this down and build a highway? There are 25,000 people here for this festival today. "And by the dint of our efforts, this little band of a couple of hundred people created the idea that there was an army of people here making this place happen. And that was really part of the South Street story."

We joined a parade around City Hall

Joel Spivak, an architect who worked on Lickety Split and Black Banana, suddenly realized a highway was going through the South Street neighborhood where he lived and worked. So he got active. "I got involved with 'the Polish women (the mothers of Marge

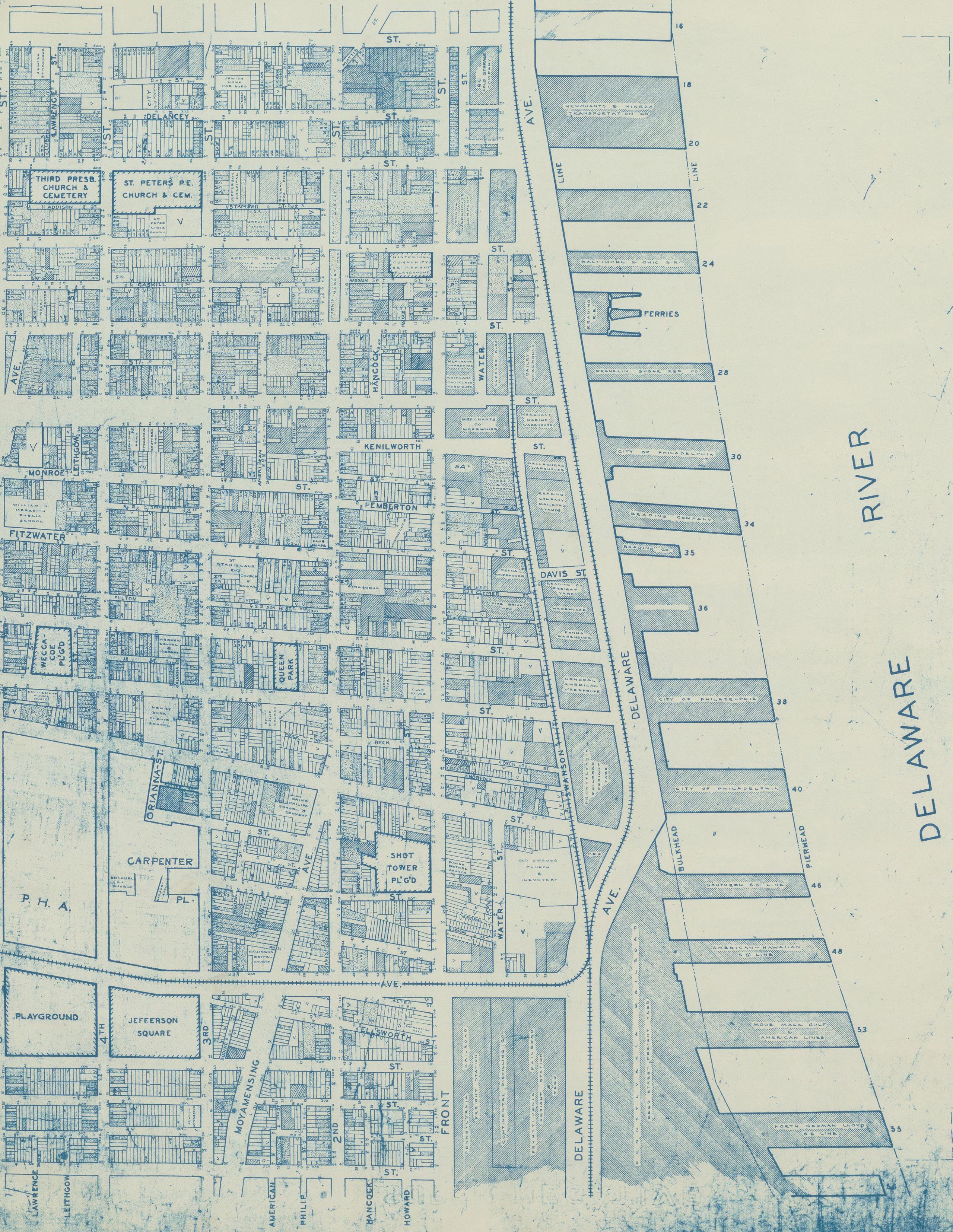

A different view of the Crosstown Expressway. 6

Schernecke and real estate maven Kathy Conway), and their friends. "One day they said to me, 'We want to have some kind of demonstration about the highway.' "Cmon," 'I say to the women,' "we're going to make these … one-by-two signs and we went to City Hall. So we're in the middle of City Hall, we were walking around the courtyard, we have our signs and are trying to get some attention … and I hear a marching band. "So I walk out of the South Portal and see that there's a parade coming around City Hall with dignitaries and cars and all kinds of festivities. "So I called all the Polish women and I said, C'mon, after this band goes past, there's about 50 feet to the next band, we're going in. "Are we allowed to do this? 'I said. what are they going to do'? "So we got in the street and came around city hall. There was a grandstand and the mayor, and the TV was there, and all of a sudden eight or 10 Polish women and me were on TV with our signs."

2 incidents with guns

David Auspitz discussed neighborhood protests.

"One was the incident of the Globula Globula machine. PennDOT set up some kind of a machine that made cement 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. (It sounded like Globula, Globula.) And it was driving everyone in the neighborhood crazy. Literally you could hear it. No sound barriers. Everybody was complaining.

We called PennDOT. One night and I won't mention the name, somebody actually fired a shot with a rifle into the Globula, Globula machine. And the police could trace it. They knew exactly where it went to, and everybody denied it. No witnesses. …And the next day at 5 o'clock, they turned the machine off.

"There was also Councilman Greenberg (Melvin J. Greenberg in 1979) …he was a second-term councilman from the northeast and he started a whole campaign against Queen Village … we are keeping his constituents from getting to the Spectrum and to see the Flyers and everything and he's bringing his people down to South Philly to Queen Village to drive around and protest stopping the I-95 ramps.

Plus .. help from the police

So … he's going to show us what it's all about. The night before he came down, somebody called the police. They found a rifle along the route that he was taking. He also never came down.

"Marge called for a giant rally at 3rd and Lombard to protest the Crosstown Expressway … and about six people showed up. "

But Civil Disobedience with Inspector Fencyl was there. WPVITV's Channel 6 was down there, too.

"Finally Fencyl said, 'here's the deal.' "He had all his officers – they were in civilian dress – take off their armbands." They also took off their badges and … they took our signs and … put them like this (over their faces). There were more police than there were protestors. We walked around in a circle, probably about 6 feet. It came off on channel 6 like there were hundreds. And they literally took the pictures and everybody went home. That was it."

We helped bring noise barriers to I-95 Conrad Weiler helped educate PennDOT about noise abatement. "After the Crosstown was killed for the third time … then about three or four months later, lo and behold, they didn't take the ramps off of the plan to I-95. And they said, 'Well , OK, the traffic will just go along your local roads.' So that was the start of the fight against the ramps." "As a result of the ramps, we got noise barriers … the first ones in Pennsylvania. I went out to Minnesota and took pictures and studied out there. So I brought it back to PennDOT and they said, 'Noise barriers. Whoever heard of them?' So it was really I guess a 15-year struggle." "It really was a change in the way we saw cities, from this topdown almost Stalinist central planning of everything to really 'we're a people-up approach.'"

These are just highlights … For more on Rick Snyderman's vivid depiction of Rounds 1, 2 and 3 against the Crosstown, and the Weekend Markets the South Street Renaissance brought to Headhouse Square, see the complete YouTube video: https://qvna.org/2017/11/13/how-philly-neighborhoods-killedthe-crosstown-expressway-video/