BLACK VERNACULAR The Phenomenology

of Black Domestic Space

QUINTON J MASON

BHA

Thank

BHA

Thank

1. We acknowledge that spaces are not what they are without the people.

2. The artifacts in BHA serve a purpose beyond their aesthetic design.

3. There must be genuine intentional celebration of Blackness in public space.

4. Understand what your privilege is, and use it to correct the systemic foundations of our society.

5. Acknowledge past hurt and understand our shared history is crucial to move design forward together.

6. Prioritizing human needs over financial and code-based designs is vital.

7. BHA preserves the stories of Black individuals in built environments, helping to combat the erasure of Black communities.

• Guest should feel a sense of belonging while at Black Home Archive©.

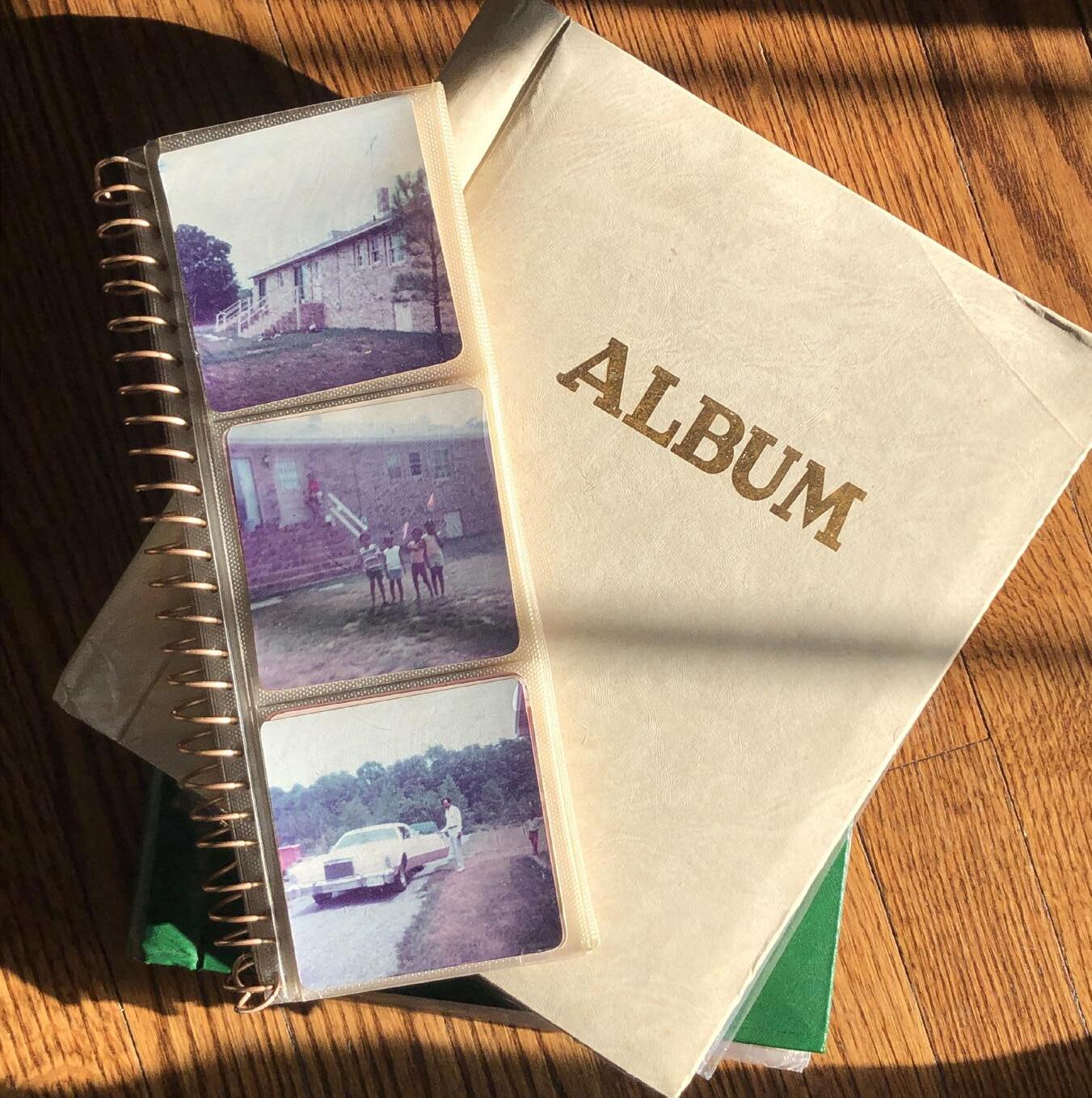

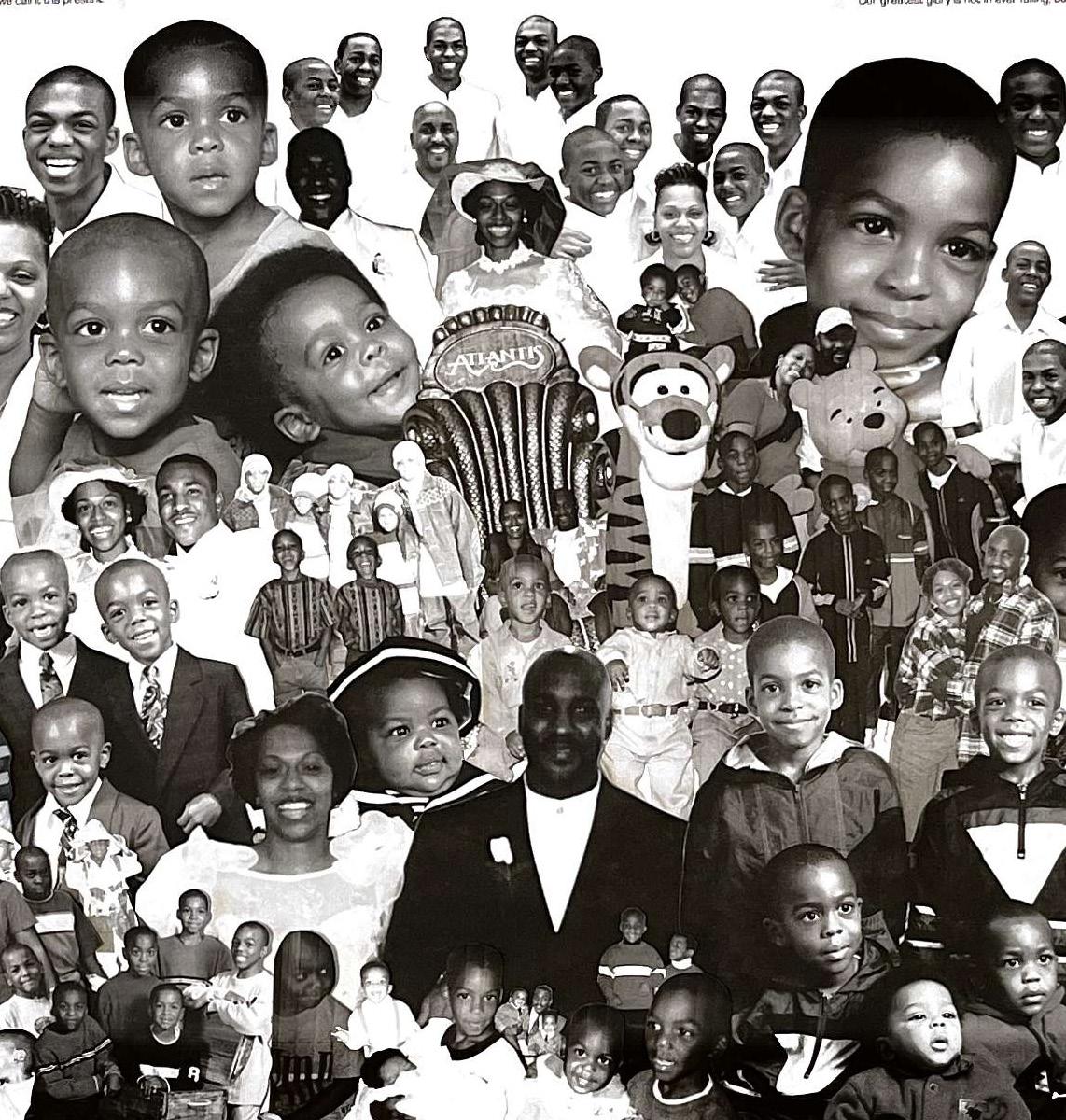

• An extension and digitization archive of your personal family photo collection or album(s).

• Find the story your grandparent told you but can't recall the words to.

• Re-immerse yourself in tender childhood/ family memories by revisiting photos that showcase home and highlight community.

• Sharing these experiences could help someone else see a new viewpoint or show them what they are capable of achieving.

• We must acknowledge the cause and effect of American history on the built environment.

I define Black domestic vernacular as an expression of domestic life. It’s not the physical architecture of the space, it’s the phenomenological, or simply put, cultural experience of the space.

This project proposes that the creation of a ‘for us, by us’ archive of Black folk’s domestic existence would define a Black domestic vernacular for designers, giving Black people greater visibility in the design process. The archive uses a photo elicitation interview methodology to conduct oral history interviews that allow us to hear directly from participants for a more intimate way of understanding their stories. Analysis of the responses identifies trends that serve as the basis for visualizations that aim to preserve the memory of place when paired with the oral interviews and the photo collection. This combination of mediums aims to bring the untold stories of Black communities’ to light while showcasing the beauty and complexity of Black spaces (scan QR code). I hope to inspire a deeper appreciation and understanding of the diverse experiences that make up our society, and celebrate the unique ways different cultures create and utilize their intimate spaces.

The follow themes are a result of the interviews conducted.

• Homesphere is the Black interface with the white world.

• Homeplace looks at viewshed and who gets to look inside.

• Green Space is a connection to food and its source.

• Interiors examines the routines and use of space.

• Identity shares personal experiences of self-discovery.

1 open camera app 2 focus the camera on the QR code by gently tapping the code 3 follow the instructions on the screen to complete the action

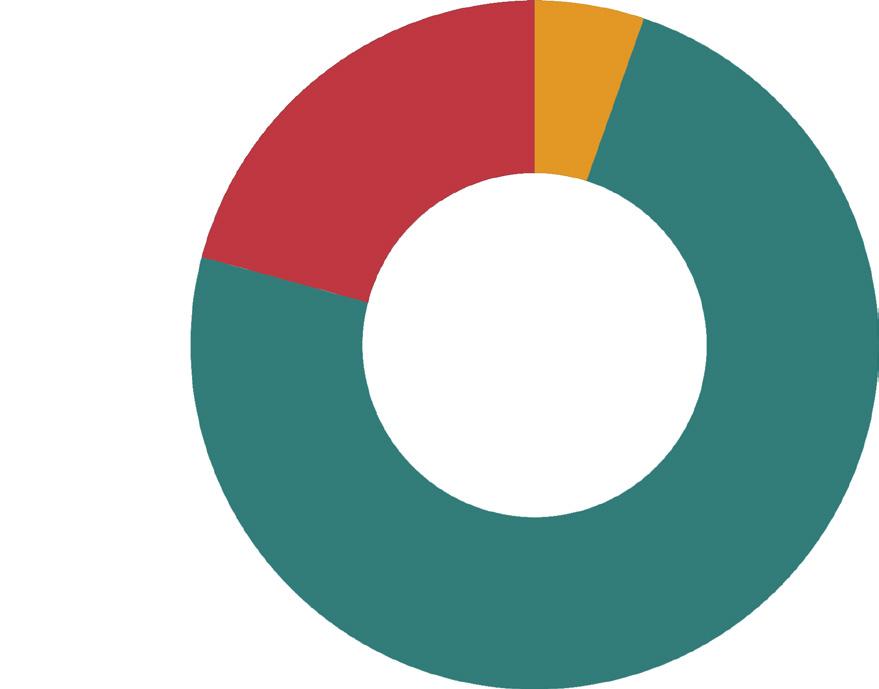

42% 58%

Quinton (Q): Where else do you find community?

Holly (H): So I'm in a sorority. I'm a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, if you can't tell. (points to plaque on the wall) Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Incorporated. I joined in the graduate school I didn't join in school. I really had a sense of community in school. It was so segregated...

H: …for us at UVA, like I said, the community is that's the reason why we're so tight, because, you know, everybody's going down Rugby Road, which yeah, around my fourth year we started going and whatnot, but it It just got to a point where, you know, the community could only convene be a community on the weekend. On the grounds. It looked like a historically Black school. And so, yeah, and so I felt a sense of community. Does that make sense? So for me, yeah. My mom had joined graduate chapter in 1980. I knew I wanted to be one, but I wasn't like so like, "Oh, I gotta be, I gotta, I gotta be now, I gotta be now" kind of situation. I think that once I graduated, and I lived

in New York, I worked and lived in New York, I think that's when I was like, Man, "I wish I was an AKA." I need community I need I need something. I don't know anybody here. I have no family, I have no nothing. And I was watching girlfriends who were in sororities and friends who were in fraternities or even other types of masons, you know, etcetera, find they're, you know, these these social organizations out of state and get into involved in those organizations and find that sense of community when you're in a place that you've never been before.

31:57 — 35:07

Q: With finding community through your sorority, how did you know that was community?

H: … that's when you have this feeling or sense of oh my gosh, this is what I'm talking about in terms of community, right. This is how I felt being in my neighborhood. Right? This is, this is what I want my children to feel like this sense of community no matter their path, and you know, and no matter where they are. Always feeling like there's a community I have support, it's a safety net. Let's be realistic. Okay. The idea is safety. Right?

Mason, Q. (2023, March 09). “BHA interview” Holly explains community [oral history][audio]. Black Home Archive. 27:27 — 31:19

In an interview with Holly Alford, she explains how she was seeking community while away from home, her house, and her blood family and wanted to escape the typical learning canon of public or private Predominantly White Institutions (PWI) or organizations. The genuine celebration of being Black in public space, this is often limited to sharing with community or, as Holly puts it, the “idea of safety,” Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were often these spaces for the Black community.

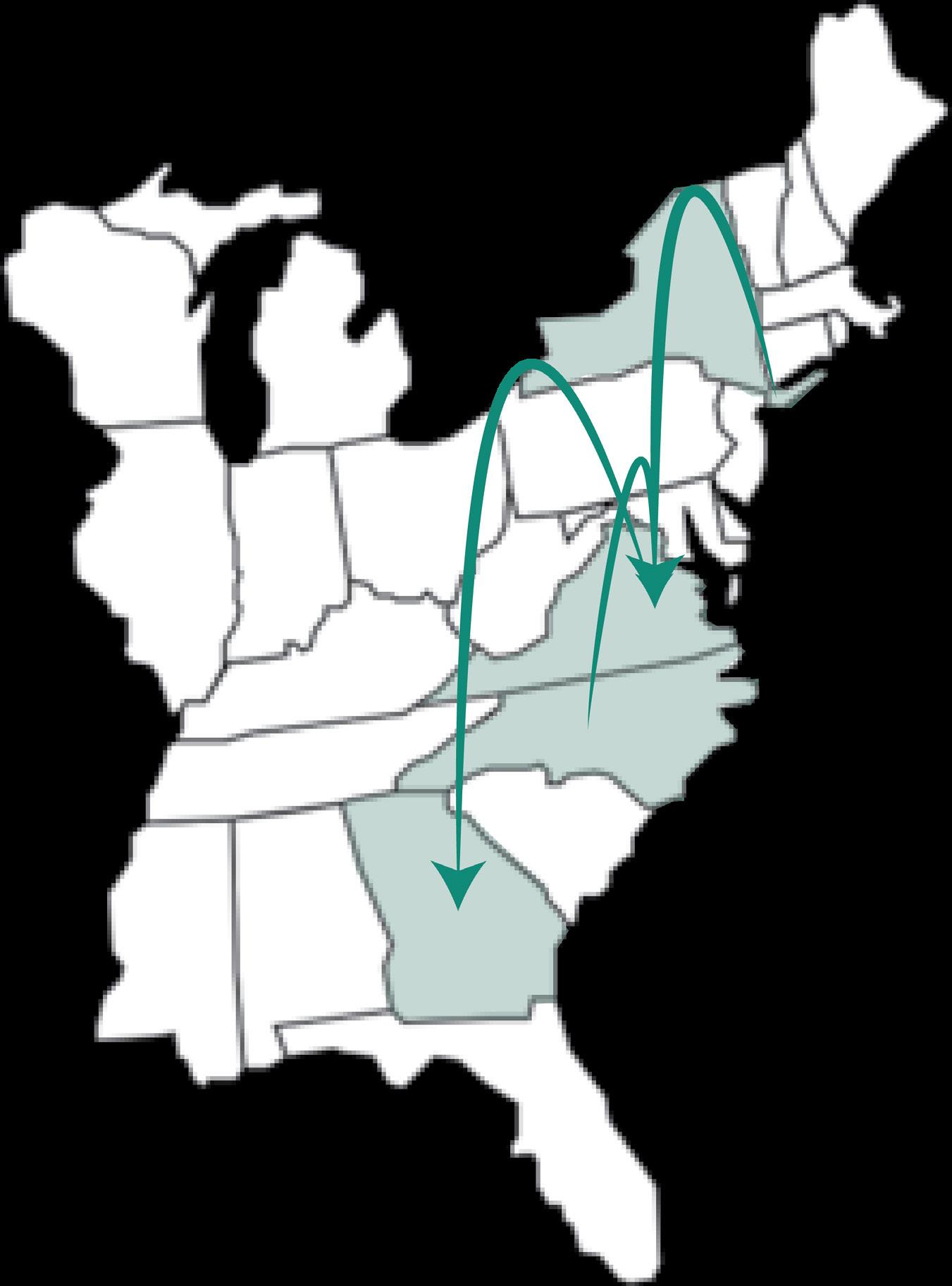

HBCUs were founded on the belief that every student deserves access to a college or higher education, dating back to the early 1800s. When segregation was legal, these establishments began to take shape and grow, providing Black Americans with opportunities to pursue higher education. Today, students of all races are welcome at historically black colleges. HBCU and the Divine Nine (D9)—”HBCU + D9”, the title of this piece, illustrates the 107 colleges in the United States that are identified by the US Department of Education as HBCUs. These nine Black fraternities and sororities have been around since 1906 and continue to be a major cornerstone of community in America. The “Divine Nine,” fraternities, and sororities were founded to help Black college students interact with one another and form support networks. D9 organizations are community service-oriented and have lifetime obligations, whereas other social organizations are not, and engagement is generally restricted to their time in college.

Membership in a D9 organization is selective, and there is no recruiting. You must also not be a member of any other Greek organization in order to join a D9 organization. Honors groups are the lone exception.

Many Black folks, spend their youth navigating the nuances of what it means to be Black in America. From generation to generation, they’re taught by elders not to act a certain way, when leaving the homesphere, or out in public for fear of criticism and safety. Celebratory independence milestones such as school or earning a driver’s license easily become overshadowed by “The Talk”. This refers to a conversation that Black parents in the United States feel required to have with their children and teenagers about the risks they face as a consequence of racism or unjust treatment from authority figures, law enforcement, or other parties, as well as how to deescalate them. When it comes to this understanding it carries over into the indoctrination of our school systems as far as what’s deemed of importance to be a productive citizen in society.1 The Black interface with the white world is an extension of the homesphere.

1“Home.” Center on Education Policy, https:// www.cep-dc.org/. Accessed 30 Apr. 2023.

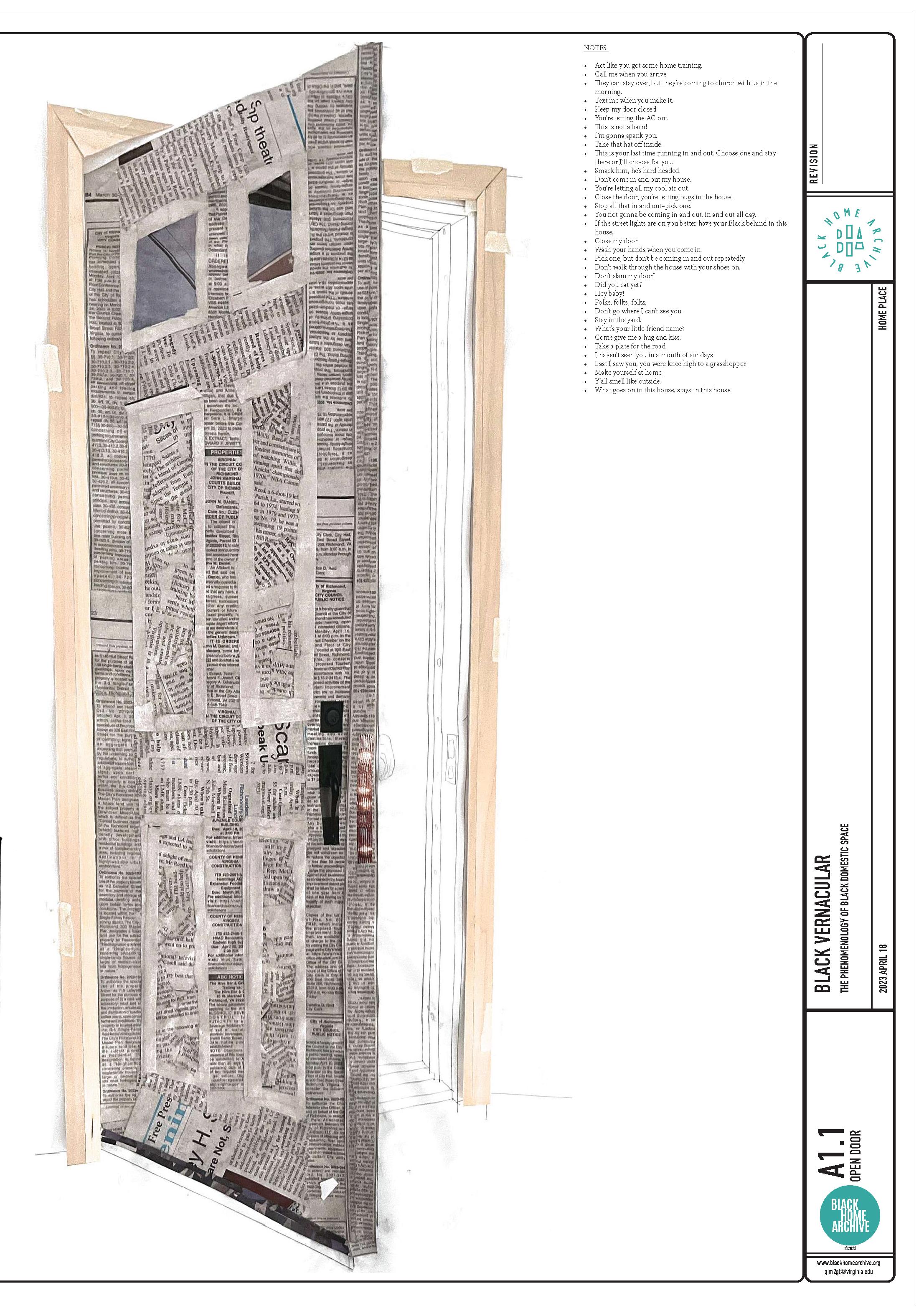

• Act like you got some home training.

• Call me when you arrive.

• They can stay over, but they’re coming to church with us in the morning.

• Text me when you make it.

• Keep my door closed.

• You’re letting the AC out.

• This is not a barn!

• I’m gonna spank you.

• Take that hat off inside.

• This is your last time running in and out. Choose one and stay there or I’ll choose for you.

• Smack him, he’s hard headed.

• Don’t come in and out my house.

• You’re letting all my cool air out.

• Close the door, you’re letting bugs in the house.

• Stop all that in and out–pick one.

• You not gonna be coming in and out, in and out all day.

• If the street lights are on you better have your Black behind in this house.

• Close my door.

• Wash your hands when you come in.

• Pick one, but don’t be coming in and out repeatedly.

• Don’t walk through the house with your shoes on.

• Don’t slam my door!

• Did you eat yet?

• Hey baby!

• Folks, folks, folks.

• Don’t go where I can’t see you.

• Stay in the yard.

• What’s your little friend name?

• Come give me a hug and kiss.

• Take a plate for the road.

• I haven’t seen you in a month of Sundays.

• Last I saw you, you were knee high to a grasshopper.

• Make yourself at home.

• Y’all smell like outside.

• What goes on in this house, stays in this house.

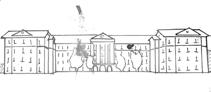

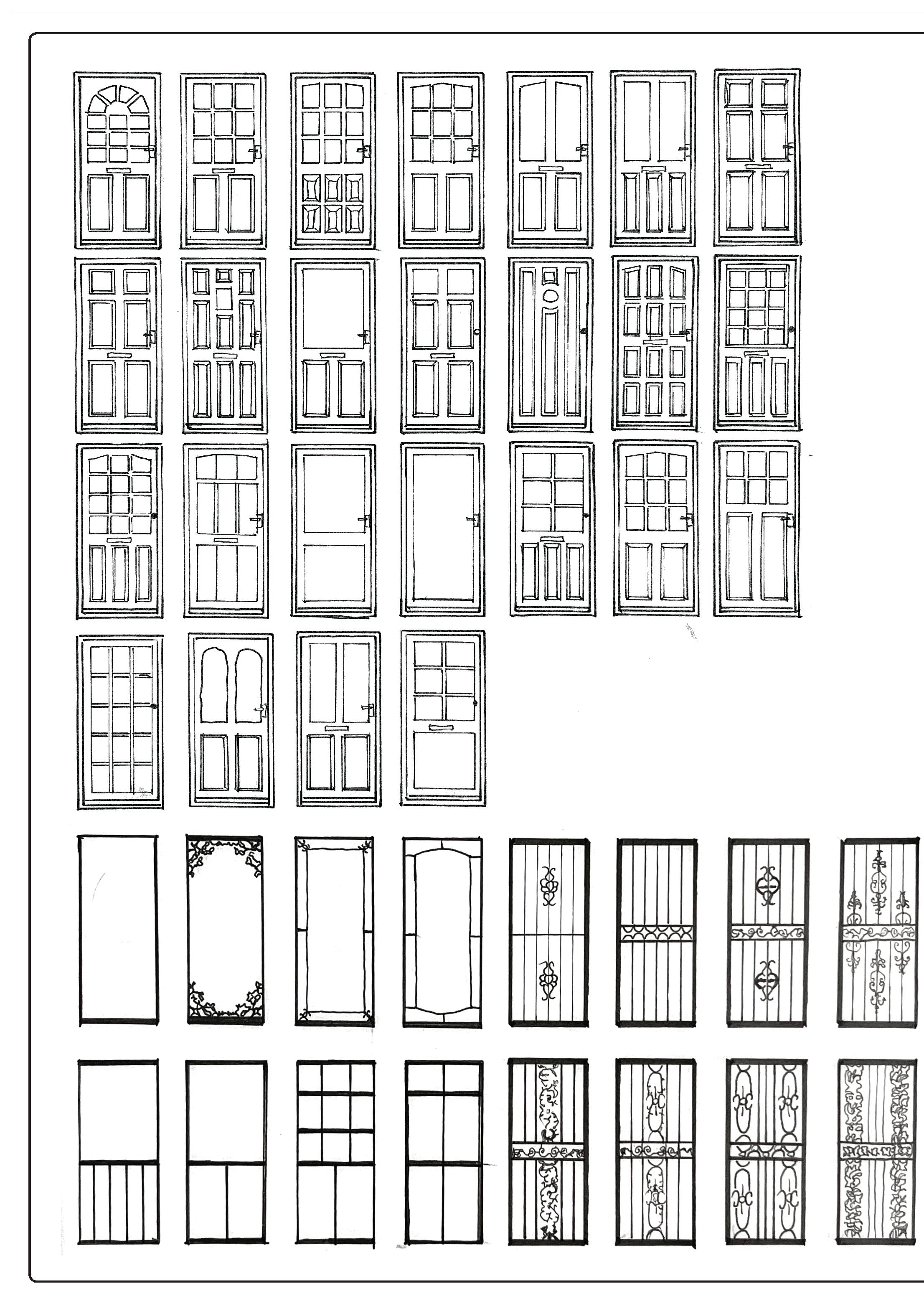

Referring to the drawing, Open Door combines African American Vernacular English (AAVE) as well as colloquial phrases and a front door to define a Black Vernacular Aesthetic (BVA). Concepts surrounding inside and outside were recurring in the interviews conducted. These phrases provide a language to a homeplace aesthetic for the life lived on the other side of the threshold by the residence. Evident in these phrases is the occupation of both inside and outside of the house.

This occupation of the outside as a room is a tradition from West Africa, seen in practice by ‘sweeping the yard’ as if it were an inside space. “You’re letting all my cool air out”, tells us the high priority of energy efficiency within BVA. Behind this closed door there is a freedom to express ourselves in our own way. When we leave this homeplace there’s an expectation that you should limit these expressions in order to be accepted in Western ideals of how society should behave. This is on display in the suburban model of dwelling. After the Civil War particularly in the South the removal of the front porch, stoops, and overall occupation of life in general was removed from the public view of the front yard. After 1959, desegregation expanded, marketing and design were increasingly white washed. The desire to force the human occupant in the house and out of the sight of those in the neighborhood. This whitewashed Western imagination of home still pervades architectural design philosophy.

In today’s political climate there’s pressure to design inclusive spaces. This is impossible to do without addressing the problematic systemic conditions that cloud our imaginations surrounding the functionality of public and private space. Examples of this can be understood through the removal of the Berlin Wall.1 It’s beyond time to address the effects of a flawed systemic system implemented through the built environment. Referring to the phrase “open door” there’s a reference to the freedom of access into a space that you otherwise wouldn’t get to experience. Dr. Andrea R. Roberts, planner, historic preservationist, scholar, and founder of The Texas Freedom Colonies Project, writes about the phrase “homeplace aesthetic” referring to how homestead preservation conjures bell hooks’ conceptions of “homeplace” and “aesthetic inheritance.” It is a vehicle for identity formation and attachment to place, as well as “sites of resistance and liberation” from the white gaze.

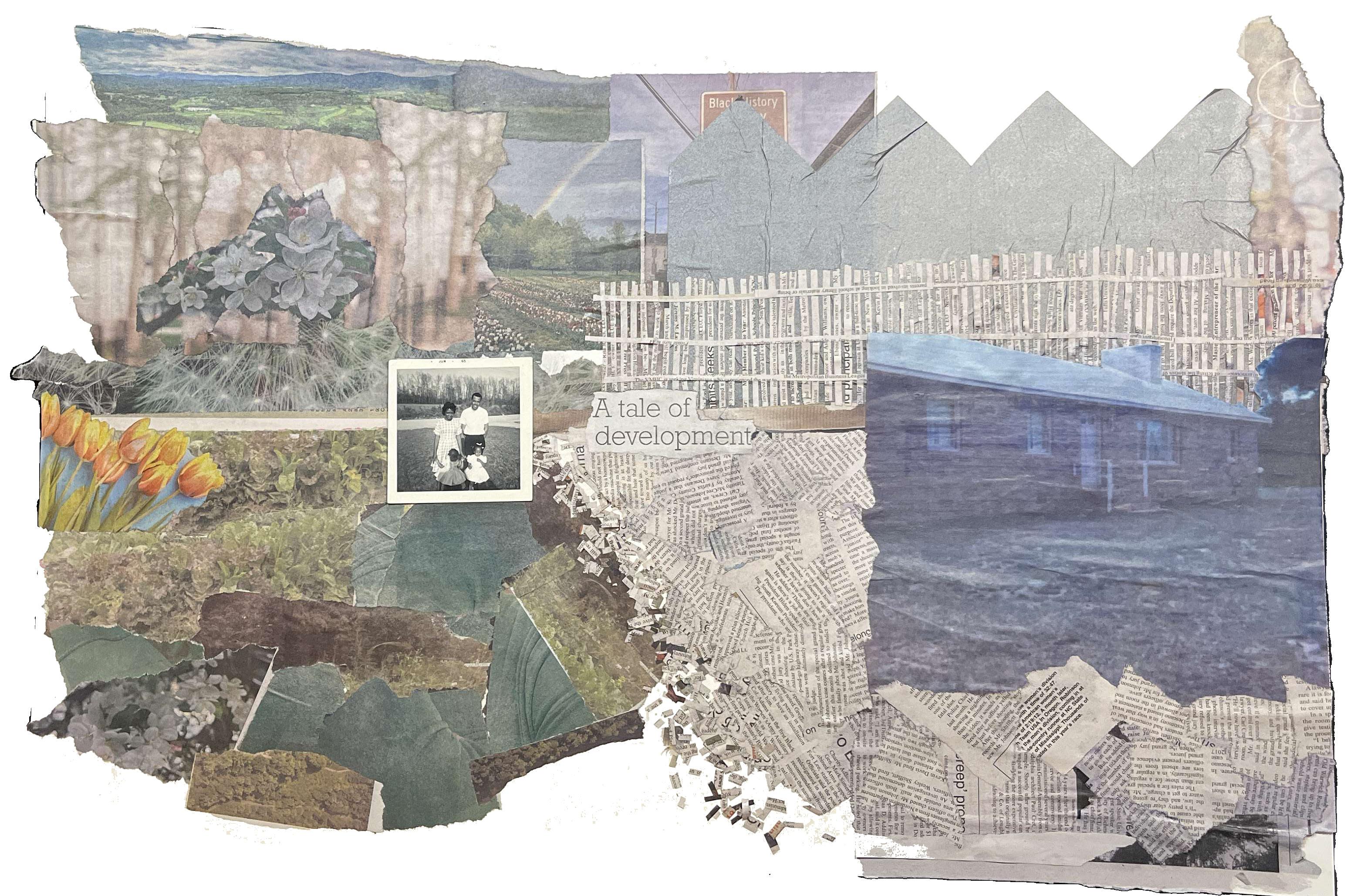

Theodore (T): yeah, oh shoot that will happen. yeah, bring back memories I tell you that. See that’s us in my parents front yard and you see where the condos at across the road now. that’s, that’s that field right here where those condos at now. Right over there.

Quinton (Q): Does that change how you feel about home?

T: yeah, it does, it does, it does, it don’t make it feel like home anymore you know it kind of takes away all that that home feeling. Yeah. When you got to look at those condos and things well we’re used to looking at open land or just another single family home it makes a difference.

Q: Has there been talk about coming on this side of the road?

T: No but we do we know that they want it because, you know, their actions say.

Mason, Q. (2023, February 03). “BHA interview” Theodore explains feeling at home [oral history] [audio]. Black Home Archive. 45:47 — 46:50

Theodore, 80 years old, at the time of this interview describes a black and white photograph of his family in a rural setting and reflects on how the change in his viewshed no longer makes him feel at home as a result of the development of tri-level townhomes (referred to by Theodore as condos) within less than 200 feet (61 meters), or the equivalent of 7 telephone poles laying tip to tail, from his front door, resting at a higher elevation than his single story, rancher style house. Displacement is not a new concept in this field. The native Youghtanund peoples were the first to feel its effects to make way for the Carter Plantation–used for tobacco production, followed by sharecropping. After Theodore’s grandfather’s emancipation in 1865, Theodore’s family worked to own ~154 acres (62,3216 square meters). This land was then cultivated and designed for the lives of Theodore’s family for generations to come. During this time, he has come to understand home and its inherent connection to the land.

This is understood as a “homeplace,” a vehicle for identity formation and attachment to place, as well as “sites of resistance and liberation” from the white gaze. Theodore is all too accustomed to the experience of being watched--now by the residents of the condos as well as the developers of these projects--every time he looks out his window or walks to his mailbox, due to the proximity of the condos’ construction and the towering views over his home. This surveillance has disrupted his sense of homeplace and

his ability to feel a sense of belonging within his community. It highlights the power dynamics at play in urban development and how marginalized communities are often pushed out of their own neighborhood. This erasure manifests itself not just in the built environment but also the legacy of the people that came before.

Black men have the lowest life expectancy in America1, this is due to senseless gun violence, over policing or surveillance which can lead to incarceration, and a variety of health complications, this gets compounded by the media’s portrayal of the “looming” assumed threat of their pure existence. Aging in place is for too many brothers a reality never seen, experienced or considered. This is a result of displacement methods, today commonly referred to as gentrification. In her book Root Shock, Mindy Thompson Fullilove, MD describes Root shock as “the traumatic stress reaction to the destruction of all or part of one’s emotional ecosystem.”2

1 Bond, M. Jermane, and Allen A. Herman. “Lagging Life Expectancy for Black Men: A Public Health Imperative.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 106, no. 7, July 2016, pp. 1167–69, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303251.

2 Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Root Shock: How Tearing up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do about It. Second

Quinton: Where would you all gather as a family? I know you mentioned going watching TV together, and playing outside. Where was the communal space or area?

CM (59): So, if it was just as family, we would go in the family room a lot. Where, because the one floor model TV that we had to literally go and change the channel for our parents was in the family room and it was a nice sized floor model TV. But we would often times sit on the floor and our parents would sit on the furniture and stuff but we didn’t mind sitting on the floor back then. But we mostly sit in the family room it was just us but when we got together for holidays, we would go to my grandmother’s house, which was two houses down and she had three bedrooms and a bath. But we made it work. She had seven children and then the children had children so we all-- we was in every room in the house but we was all sittin down eaten and you know what’s the matter got finished then somebody else would sit at the table to eat but we made it work. And that was the fun part about it when you got together and grandma cook for everybody or you know, she did a lot of the cooking so that’s I learned how to bake now. Just sitting there watching her and putting-- her palm was her measuring cup. So she didn’t measure a lot of stuff she would say you just put a little bit in the palm of your hand and she would throw it in the bowl. And she would put a bowl in her lap, sitting right in between her legs and she would just mix it you know mix it, mix it, mix, mix, mix it and so that’s I learned how to do

a lot of my baking so I was actually a baker before I was a cook because she baked a lot of desserts. And so I wasn’t worried about the you know, steak and stuff like that. I want to know how to bake the cake and the cobbler. So that part was neat. So everything that, anything she could teach you about baking, if you sit in the kitchen long enough with her, she would tell you how to do it. So when people call me now, and say, “what’s the recipe?” I don’t have a recipe. I don’t measure a lot of stuff. So that was how I came up. She just say, and you know, “see it’s supposed to look like this--it’s supposed to feel like this. Like, okay, whatever that mean. But I just in watching her and seeing what she did. I was like Okay, so now when I make crust, I be like, “Oh yeah, it’s gonna be good. It’s gonna be flaky.” Just because of the texture or the look of it. So just watching her do it was like “okay”, so that was neat. I wish we had gotten a few more of her recipes, which weren’t recipes but; to learn how to bake different things. [yeah]. So that part was neat.

When asked about where her family gathered, CM shares memories of gathering in the family room around the TV. For holidays or other large family gatherings everyone would gather in her grandmother’s cinderblock home just a few doors down. During the preparation for these events CM would watch her Grandma measure ingredients in the palm of her hand without a recipe. Today, on the occasion CM may be seen using a measuring cup or recipe, however, she hasn’t forgotten the tradition of sharing her Grandma’s lessons on how to bake using what God gave her.

Bill Withers, an American singer, and songwriter, performed “Grandma’s Hands” in 1971. Because AfricanAmerican families are traditionally matrilineal may be what makes “Grandma’s Hands” particularly recognizable to Black folks from the South. The song’s major concept is the protecting and nurturing energy of the hands, which always left something sweet.

It’s important to note that these experiences similar to baking by using the palm of your hand to measure can be used in design. “Anthropometry can be applied to design, but the dimensional data of the human body must be both static and dynamic. This measurement needs to be taken when someone moves, does activities, or participates in work. Additionally, anthropometric measurements cannot be equated for people across two geographies, so one cannot use measurement data from the Philippines to design architecture in the USA.”1

1 Anthropometry In Architecture Design | Urban Design Lab. 26 Jan. 2022, https://urbandesignlab. in/anthropometry-in-architecture-design-urbandesign-lab/.

10:24

Quintez (1995): I think for me, like, the terms house and home, it could be because this is the house that I live in is the only house that I’ve really ever lived in. So for me, like, house is the home.

9:27

Quinton: What’s your understanding of the terms house and home?

32:26

A.Mason (1968): Okay, well, where I’m from? I’m from the country. Roots and my mama. So I considered house and home the same thing. We described it as the same thing.

9:42

C.M. (1963): To me when the difference I guess house was always home my home was always a house we you know we live where we live.

8:39

R.Mason (1996): Um, like I said home, the running joke is what Home is where the heart is. But yeah, I going on trips and you know, having these wild adventures and stuff and coming back. All I know is I’m just excited and ready to be back home. There’s no place like sleeping in your own bed and being in a place that’s very familiar to you.

Theodore (1943): Well a house is just a building a home is what you make it and now what did you what how what you have in it and how you perceive it to be home it’s just a little more than a building.

9:20

Dayquan (1993): So for me a house is somewhere where you reside, and I think about home, I think about Home is where the heart is, is where you feel most comfortable where you feel most loved.

12:36

Tiwian (1990): To me house is a structure where you’re staying or live or have lived and home is probably more of a feeling you know, wanting to be somewhere where it’s it’s comfortable and safe and where you’re where your people are may not necessarily be a house but you know you can I would consider that home.

24:31

E. Harris: (1942) Well, I guess the house is just somewhere you stay at, but a home is a way to show love. You know you’re everybody’s connected. You know, it will be a home.

25:23

Sharon (1963): And again, for us, again, my grandparents, grandma, especially his parents, and I refer to them because that’s where I live…

10:58

Andre (1994): Home I would say it’s my parents house where they currently live and it doesn’t matter who’s in that house with us because that is home. And I think a lot of my childhood memory is routed to that specific location where it’s that that’s home to me.

22:28

Craig (1963): So Home to me is, is the people that not necessarily live with you are invited into your personal space. And anybody that’s within your personal space. That’s your comfort zone. That’s your, your trust zone that, you know, you know, where you can let your hair down for say, yeah, let me let my hair down. I’m sorry. Yeah, yeah, yeah. So that’s what a home is a house to me is, is a place where you can you know, have some friends to come over but they’re not in your trusted circle. houses where you hold your physical possessions, you know, but a home is the people that that not necessarily live there but people that you invite, and you trust into your inner circle.

30:36

Dora (1953): A house can be a place that you reside. And you could have 10 people in there. But if you’re not happy, you don’t feel welcome–it’s not a home. So Home to me is where you can, everything anything could be happening at work out in the street. But when you say there’s no place like home, that’s because that’s your safe haven. You should be able to go home and have peace and love when you can’t go anyplace else. That’s my difference.

23:52

Paulette (1960): House and home, House is the building per se. You can live anywhere and it can be your house, but you have to make it home and you make it a home by your family, or experiences you’ve had or in my son generally says, your home also is in your heart. Anyway you’re at it can be your home. So I guess I kind of feel the same way.

29:43

RW (1973): Home? My grandparents was where I felt safe at where I felt like I could unveil, nonjudgmental just be. My house was that’s where I live. That’s where I reside. Just the place is a structure is a building.

20:31

LaToya (1982): …in the simplest terms, like when I think of house, I think of like, a physical structure. When I think of home, I think of a place where there’s love and affection.

21:27

AW (1970): Um, I would say a house is just somewhere where you, you know, just a structure in the home is more something that you it’s, it’s a place you call home, it’s your safe space, it’s peaceful. You look forward to goin’, you know, you pass houses and on the street, but you look forward to going home? And home is something you can call your own, basically.

19:29

Dale(D) (1989): House is a place of residence,

Elysia(E) (1990): physical structure.

D: And a home is where you’re most comfortable where you find comfort.

D: I’d say every place that we’ve resided together, was our home. Absolutely. And it doesn’t have to be one place. And that can be levels too because I feel like when I go back to Brooklyn, I get a sense of home as well like being at my grandmother’s house. Is a sense of home for me.

E: I was gonna say that as well like going back to the place where I grew up in Rockville. Even though I no longer live there, that still feels like home to me, even though this is my home where we live now. That also still feels like home to me as well.

41:10

Holly (1969): A house is the structure a home is the love and the community within it.

Mason, Q. (2023, February 02 -- March 10). “BHA interview” participants explain their understanding of the terms house and home [oral history][audio]. Black Home Archive.

The phrases house and home are used interchangeably when referring to domestic or residential environments. It is critical for participants to express their understanding of the concepts. It is essential to recognize everyone’s lived experience that has shaped their notion of home. As a result, this knowledge is always developing.

Idioms like “feel at home” are tossed around as the goal for creating equitable environments. This implies feeling at ease and comfortable, welcomed, and as though you belong in a specific setting or with a group of people.

I feel that it is only through this knowledge that design will be able to approach the notion of the house. Using the responses of the participants, home can be understood as the people and feelings, and the house is the built structure to shelter and facilitate the functions of a home.

Special thanks to err’body, A. Mason, A.W., Andre Wilson II, C.M. Craig, Dale Greene, Dayquan Mason, Dora, E. Harris, Elysia Greene, Holly Alford, Latoya Gray-Sparks, Paulette H., Quintez M., R. Mason, R.W., Sharon, Theodore, & Tiwian Mason. Your contributions are absolutely crucial and I deeply appreciate them. Without you, none of this would be possible. Thank you for making such a significant impact. Shout out to all of the friends, faculty, and peers, for being a great sounding board. In the role as my primary advisor, Andrea R. Roberts, PhD., founder of The Texas Freedom Colonies Project, thank you for being an amazing mentor and for providing me with such valuable advice during this semester.

I would also like to acknowledge all of my ancestors—the ones I’ve heard stories about to the unacknowledged. It’s because of your creativity and determination to make miracles from seemingly very little that rooted my interest in the field of design. To current and future generations let this archive be the foundation for taking steps to challenge idealized Western designs of the built environment.

As I know that architecture is not a “fix-all” for the centuries of systemic racism ingrained into American culture. I truly believe that Architecture designs the future and documents the past. It is up to you as Architects, designers, educators, neighbors, family, and friends—simply put humankind—to recognize where you can make a difference in your life to have the courage to challenge the status quo and increase your agency to correct these issues.