CASTLE

VOLUME

ISSUE 03 SEPTEMBER 2018

RABY

AND PARK

ONE: CONSERVATION PLAN

Rebecca

Burrows, Dr Alex Holton and Bev Kerr

On behalf of Purcell ®

29 Marygate, York YO30 7WH www.purcelluk.com

Purcell asserts its moral rights to be identified as the author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Purcell grants the Raby Estate a non-exclusive licence to make use of the Report providing this is consistent with the purpose for which the Report was commissioned and that Purcell remain acknowledged as the author and intellectual property holder as part of any such use, in whole or in part. Purcell has no liability for use of the Report for any purpose other than that for which it was originally prepared and produced.

The Raby Estate retains copyright of all materials provided to Purcell in the production of the Report, including maps, plans and photographs. Purcell retains a licence from the Raby Estate to use and reproduce these materials within the Report.

Purcell® is the trading name of Purcell Miller Tritton LLP

Issue 01 June 2018

Lord and Lady Barnard Issue 02 July 2018 Lord and Lady Barnard Issue 03 September 2018 Lord and Lady Barnard

001_238974

RABY CASTLE AND PARK: CONSERVATION PLAN CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 0 4

PART ONE: THE RABY CASTLE ESTATE

1.0 PRELIMINARIES 07

1.1 Vision of The Raby Estate 07

1.2 Purpose of the Report 07

1.3 Identifying the Site 07

1.4 Methodology 08

1.5 Research and Findings 09

1.6 Consultation, Adoption and Review 09

1.7 Authorship and Acknowledgements 09

1.8 Navigating the Document 09

2.0 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK 10

2.1 Site Location 10

2.2 Topography and Geology 11

2.3 Ownership, Management and Use 11

2.4 Heritage Protection and Designations 13

2.5 Overall Condition 15

2.6 Character Areas 16

2.7 Built Heritage Components 17

2.8 Setting and Key Views 28

2.9 L andscape 35

2.10 Archaeological Potential 41

2.11 Location of Old Raby 43

3.0 U NDERSTANDING H ISTORICAL D EVELOPMENT 45 3.1 Introduction 45 3.2 Raby Castle, Park Estate and Gardens Timeline 45 3.3 Map Progression 63 3.4 Relationship of Landscape to Structures 78 3.5 Historic Route Analysis 82 3.6 Phases of Development 84 3.7 Historic Uses and Functions 85 3.8 Contextual Analysis 87

4.0 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 96 4.1 Criteria for Assessment 96 4.2 Assessment of Significance 96 4.3 Significance Plans 101

PART TWO: CONSERVATION FRAMEWORK

5.0 ISSUES AND VULNERABILITIES 105 5.1 Raby Castle and Wider Landscape 105 5.2 Walled Garden and Stables 106

6.0 PRINCIPLES AND RECOMMENDATIONS 107 6.1 Raby Park: Principles for Conservation and Change 107 6.2 Recommended Actions by Theme 108 6.3 Raby Park: Emerging Research Framework 112 6.4 Archaeological Strategy 116 6.5 Recommended Actions by Area 118

7.0 CAPACITY F OR CHANGE 121 7.1 Introduction 121 7.2 Capacity for Change 121

BIBLIOGRAPHY 127

APPENDICES

A: List Descriptions 147

B: Historic Parks and Gardens Register 152 C: Relevant Planning Policy 154

8.0 N EXT STEPS 126 8.1 Adoption and Review 126 8.2 Phasing and Implementation 126

Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

VISION

The Raby Estate is forward looking in its vision for a sustainable future for the Grade I listed Raby Castle and its surrounding Registered landscape. Lord Barnard aims to create a viable, outward facing offer for visitors through a shared understanding, a passion for the Estate’s rich history, a safeguarded natural and historic environment, strong community ties and access for new audiences.

This Conservation Plan is the first step in supporting the vision of the Estate to conserve and bring relevance back to the nationally significant heritage assets and their setting by providing a high-quality offer to visitors in a way that conserves significance and does not dilute authenticity. The document and its associated gazetteer provides a baseline of evidence for future decisionmaking. It sets out an assessment of significance, vulnerabilities that could harm this and recommended actions to support informed management and change.

The Conservation Plan has focused its emphasis on those areas likely to be areas of development in the future. The Walled Gardens and stables area has been assessed in detail, with consideration of its setting within a Registered deer park and associated historic structures. The Castle is the principal heritage asset within the landscape and while it has been assessed in relation to surroundings, it has not yet been subject to detailed analysis. Thorough analysis of the Castle will be required at the necessary stage, if proposals for change are put forward.

SIGNIFICANCE

Raby Castle is one of the most significant and intact medieval Castles in the North East, set within a complete eighteenth-century deer park landscape and agricultural estate spanning much of Teesdale. Raby has earlier origins as a Viking settlement of King Cnut, known as ‘Rabi’ in the 11th century. The Nevill family built the current structure in the fourteenth century (1367-90) and along with Brancepeth Castle, Raby Castle is part of wider development of quadrangular castles of this period in the region, built by rich and powerful families in the border region where the power of the king was weak. Along with Barnard Castle, Raby Castle is also significant as one of most substantial fortification sites in the county. Its completeness is of national significance, as a largely single-phase structure, with one twelfth century survival (Bulmer’s Tower) and later eighteenth and nineteenth century infill and additions. Associations with masons and architects such as John Lewyn (Durham Cathedral), William Burn, John Carr, David Garrett and James Paine are important and the fact that no archaeological investigations have ever been carried out here is of high evidential value.01

Raby Castle gives the impression of a medieval fortress on to which a rich nineteenth century Jacobethan scheme has been applied, punctuated by fashionable Gothick additions in the eighteenth century, which have historically been overlooked. Originally moated and accessed via a drawbridge, the Castle was built as a palace fortress and as a symbol of hegemony. It is characterised by a sequence of massive towers linked by curtain walls, crowned with crenelated parapets and machicolations, illustrating chivalric lordship through its heavily militarised aspect.02 Extensive repairs and alterations in the mid to late-eighteenth century were carried out by renowned architects, creating Palladian and Rococo Gothic rooms, followed by a comprehensive mid-nineteenth century scheme by William Burn.

Following the Nevills’ unsuccessful the Rising of the North in 1569, Raby Castle has been the home of the Vane family since 1626 and is characterised by its undulating parkland, and collections of art and artefacts. The medieval deer park associated with Raby Castle is an example of the 3000 deer park surviving nationally, and illustrates the activity of medieval nobility, which continue to have a powerful influence on English landscapes today. The landscaped parkland of the mid-eighteenth century visible at Raby Castle today is Registered as a park and garden of special interest and was reworked several times within the eighteenth century, in a pattern seen across the region. Garret, Paine, Carr, Robinson (Auckland Castle) and Joseph Spence all had an input into the design that has survived remarkably intact into the twenty-first century.

The Walled Gardens and stables at Raby Castle are of interest for their close visual and functional relationship with the Castle. Early examples of walled gardens from the seventeenth or early eighteenth century could be areas of conspicuous display and highly visible, such as those at Auckland Castle, however as these became more common in the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century they were generally laid out away from the main house.03 At Raby Castle, the gardens remained visually dominant within the landscape, as although there were no connections from principal rooms within the Castle (which all face south), the principal view of the south elevation across the lakes also draws in the gently sloping walled gardens and stables. The reason for this location may have been a continuing matter of display, showcasing exotic plants, but was also a practical response to the evolution of the location of the medieval village of Old Raby and its field systems.

Taken as an ensemble, the Walled Gardens and stables are significant as an intact and well-organised area, formally developed in a short period to serve the evolving needs of the Castle. It incorporates the household supply of vegetables, fruit and flowers (tied to display of prestigious horticultural skills), the accommodation of expensive hunting and carriage horses (which in itself was an area of display and a newly-evolving fashion with associated design innovations) and the ancillary functions to service the Castle including meat, dairy, joiners, masons, gardeners and farrier. The formalisation of these services as part of the clear intent to move the old village away from the Castle is of interest and fits into a pattern of landscape change seen nationally. The functional and formal relationship of the walled garden area within the setting of the Castle is highly significant and is relatively rare in terms of visibility, if not function.

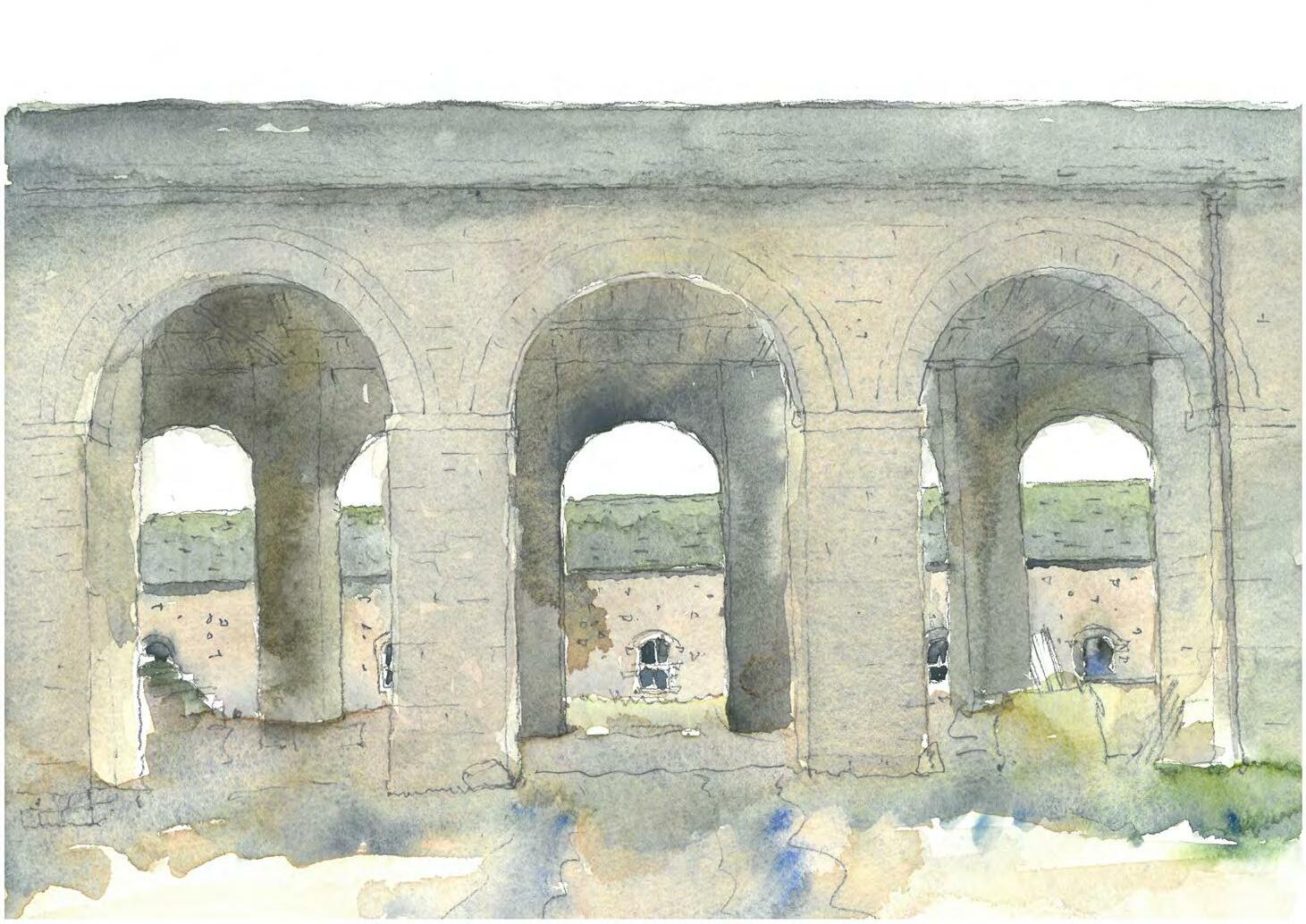

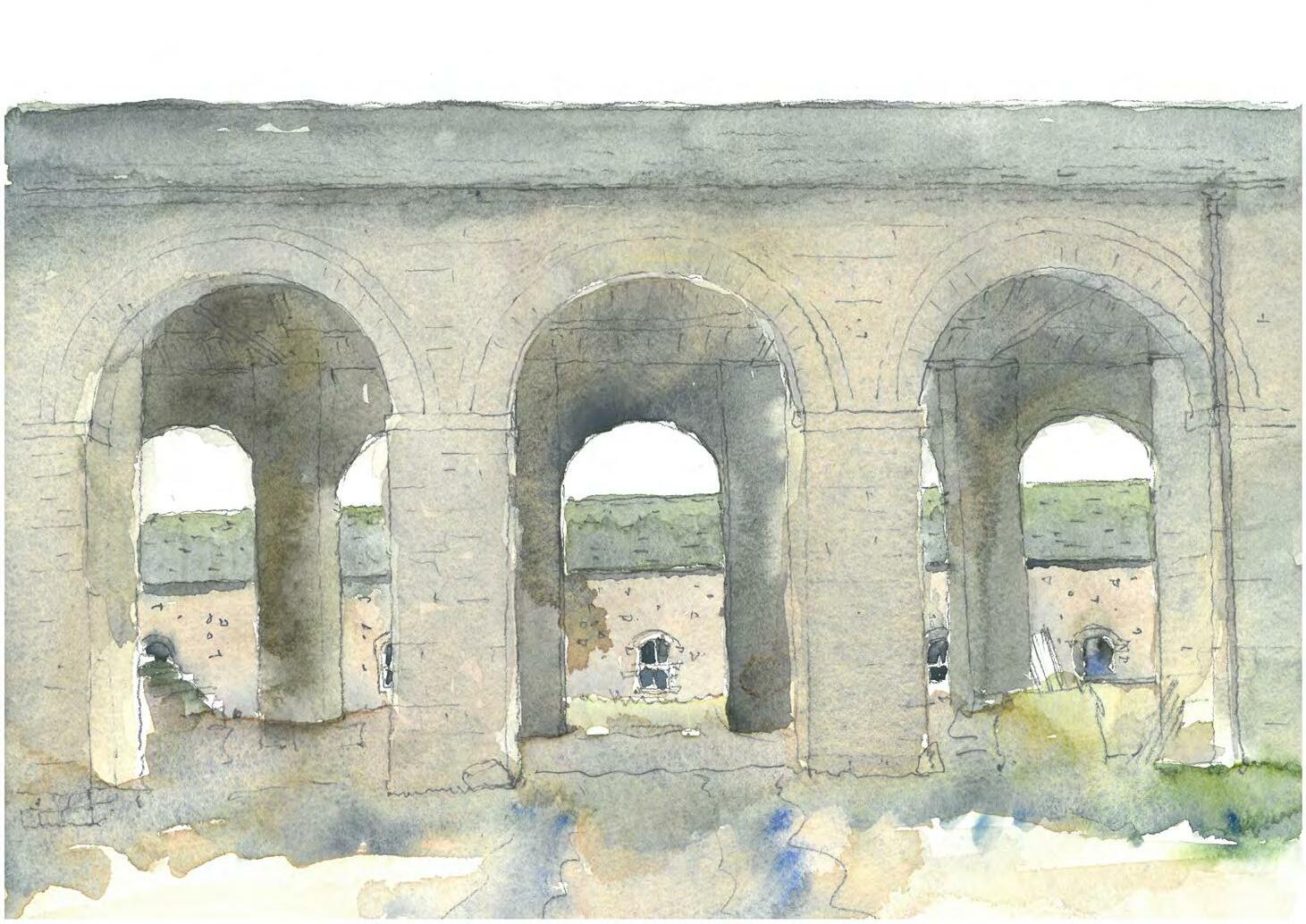

O ther structures within the landscape are typical features constructed as part of an eighteenth century landscaped park, including bath houses, ice houses, follies, temples and model farms. The Riding School is a rare building type, one of only 14 known examples from the peak of construction in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century.04 The grand architectural statement of the hay barn is also an unusual and early example of an agricultural building. Home farm, which is outside the Registered parkland, is a notable early example (mid-eighteenth century with earlier origins) of one of a few model farms in the county.05

01 Shared Visions: The North-East Regional Research Framework for the Historic Environment, David Petts with Christopher Gerrard, 20 06

02 Shaping the Nation: England 1360-1461, G L Harris, 2005

03 https://content.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/ dlsg-garden-park-structures/heag108-garden-and-park-structureslsg.pdf

04 G Worsley, The British Stable, 2004

05 Shared Visions: The North-East Regional Research Framework for the Historic Environment, David Petts with Christopher Gerrard, 20 06

04

Contents

A s a group, the medieval Castle, Registered parkland and Walled Garden area form a highly significant group for their evidential, historical and aesthetic value. Each structure informs an understanding of its surroundings and should not be read in isolation. The landscaped park within which each structure is set is also significant, with historic routes, tree planting, designed views and ancient features all contributing to an understanding of how the Estate was used in the past. Visual and intangible connections between the Walled Gardens, Bath Wood, lakes, stables, Raff Yard and the Castle are important although some designed views and planting schemes have been lost.

F INDINGS

The conservation planning process has led to an increased understanding of the Estate. Cartographical analysis of the Raby Castle archives has provided greater clarity of dates, uses, locations, associations and significance, providing more accuracy than the designation descriptions. The archaeological potential of Raby Castle and its Registered landscape is extremely high as no archaeological investigations have been carried out and minor finds range from Neolithic to Roman and Danish phases of occupation. The assumed location of the medieval village of Raby requires verification, which could form a truly exciting and inclusive community event with non-intrusive surveys and possible excavations if development is proposed.

The Estate is well managed and maintained by the owners and the principal structures within the Registered deer park are in good overall condition. Those buildings in use within the Walled Gardens and stables area are in good condition although those in a low-level use or redundancy are declining in condition and require maintenance. The landscape itself is well managed but there remains a need to balance land management regimes with biodiversity. Loss of parkland trees has reduced aesthetic value and some newer clumps require improvement.

Current barriers to increased visitor numbers relate to a need to resolve access, interpretation, circulation, facilities and activities. The Castle is the principal draw on the Estate, but a refresh of interpretation and marketing would be beneficial. The Walled Gardens as a visitor attraction are supported by visitor facilities in the stables including a shop and tea room. Improvements to the stables area would include new, high-quality offers, physical alterations to allow inclusive access, new routes across the landscape and improved vehicular access to deal with increasing traffic.

The Walled Gardens and stables area contains a number of important designated heritage assets but is also underutilised and at risk of decline. Each structure on the site is capable of beneficial reuse and could be subject to informed change dependent on significance. The capacity and constraints on change for each structure is linked to their heritage value, the degree of past alteration, relationship to the Castle and setting, and the viability of accommodating a new use. Each component has been addressed in turn within the gazetteer. The character of this area is one of formality and functionality, which permeates from south to north as historic use changes. The polite and vernacular features of these structures will need to be sustained and enhanced as part of any regeneration. Heritage significance naturally increases the need to utilise highquality craftsmanship, materials and design, which will impact on the conservation deficit of these structures and the viability of a scheme for revenue generation.

Future development within Raby Estates will be grounded within a robust understanding of significance, outlined in this framework document and supported by additional targeted investigations if required. Any conflict will be identified and resolved, and the impact of proposed changes will be assessed as part of an iterative masterplanning and design process. Recognition, understanding and sensitivity to the value of the significance of the Estate will allow the vision of the owner to be realised in a way that is sustainable into the future.

05 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Contents

06 PART ONE RABY CASTLE AND PARK 1.0 Preliminaries 07 2.0 Understanding Raby Park 10 3.0 Understanding Historical Development 45 4.0 Assessment of Significance 96 Contents

PRELIMINARIES

1.1 V ISION OF THE RABY ESTATE

Lord and Lady Barnard and Raby Estates value the authenticity of Raby Castle and its surrounding parkland and wider landscapes. They see themselves as custodians for the family, the estate and its history, and aim to continue to care for these in a sustainable way in the future. The vision of the Estate is to create a viable, outward facing offer for visitors through a shared understanding, passion for their rich history, safeguarding the environment, strengthening the community and its economy, and seeking new and proactive ways of doing business. There is a commitment to trust, quality and good service.

The Raby Estate is now at a turning point in its history. The extensive assets and opportunities represented by the site are not currently utilised to their best advantage. Historic buildings with the potential to be put to viable new uses are underutilised and beginning to deteriorate. The aim of the Estate is to conserve and bring relevance back to these nationally significant structures by providing a high-quality offer to visitors, in a way that does not dilute the authenticity of the site as a working Estate and family home. Changes that make the Castle and Park more accessible and open to new audiences will be welcomed. Many local people have lived within view of the Castle all their lives but have never been inside. Activities that reflect the personalities of the owners will be of the highest importance.

In the wider view, the full Raby Estate provides opportunities that connect to the use of the Castle, Park and stables area. Leisure uses such as High Force, the Pennine Way and old railway lines all provide a network of links and routes that could increase footfall. Vacant farmsteads across the landscape provide opportunities for wider uses from accommodation to storage and maintenance in a way that will freeup more significant and usable spaces within the immediate setting of the Castle.

This Conservation Plan represents the first step towards an understanding of the Castle, Park and stables, and will provide a baseline of evidence for future decision-making. Lord and Lady Barnard are conducting masterplanning, business planning and marketing activities to enhance the sustainability of the Estate. A visioning activity has been undertaken in June 2018 with key stakeholders such as Visit County Durham and Durham County Council (DCC) and the condition survey for the site was undertaken in May 2018.01 An assessment of the retail and visitor offer has been carried out, all with the aim of making Raby Estates more accessible and outward facing.

The Raby Estate is well supported by statutory bodies and stakeholders in the region. DCC are committed to ensuring Raby Castle becomes a key player in the tourism and wider visitor economy of Country Durham. The Estate is a strategic priority for DCC as part of their wider commitment to increasing dwell time in the area. There is an opportunity to support the repair and conservation of the heritage assets across the Estate in a sustainable way that provides a viable new offer to visitors both locally and nationally. The vacant and underused structures within the Walled Gardens and stables area and wider within the Parkland offer high-quality and characterful spaces for new uses as listed buildings in their own right, but also set against the backdrop of the stunning Castle.

The future for Raby Estate is not one that can be rushed. An award-winning visitor offer will need careful planning, centred around a clear vision for what it wants to achieve. The strong connections and communities that will be forged during this development process will be important. The aim is to produce an inclusive visitor facility for diverse audiences centred on the offer of the Castle, which is timeless but high-quality, relaxed and uplifting, flexible, family-friendly and engaging. The Castle will offer an authentic historic experience, the Parkland will provide wide, open spaces and the gardens will provide peace

01 Quinquennial Inspection, Donald Insall, May 2018 and visioning workshops in May and June 2018, facilitated by Blue Sail

and tranquillity. Overall, the site will be enticing and will seek to enhance the existing authenticity of the place, building on these qualities rather than imposing upon them.

1.2 P URPOSE OF THE REPORT

This Conservation Plan is intended to be a strategic report contributing to the successful future management and use of the Registered Park and Garden known as Raby Park within Raby Estates and will provide baseline information to contribute to an overall understanding of the significance and vulnerabilities of the place, relationships between assets, as well as highlighting areas where appropriate change could be made.

In line with the original client brief (30th January 2018) this Conservation Plan has concentrated its emphasis on those areas within Raby Park that are likely to be the focus of development and change in the future. The Gazetteer (Volume Two) of this Conservation Plan has an emphasis on the stables and Walled Garden area to the north of the Castle. While it is recognised that the Castle is the most significant asset within the Park, this is unlikely to be subject to major alteration and as such has only been assessed in its relation to its setting and other heritage assets within the Park.

As defined in the project brief, the objectives of this Conservation Plan are:

i to use all relevant accessible primary, secondary and tertiary sources of evidence and research concerning the defined heritage assets to set out the significance of the site;

ii present an overall breakdown of the values of each heritage asset, internal and external, focussing on archaeological, architectural, artist or historic interest;

iii to present a comprehensive overall assessment of the relative vulnerability of each asset and the whole;

iv to identify each aspect of the `special interest' of the asset, which may have a particular vulnerability, as informed by the above;

v to identify the limits of acceptable change to each asset, the site and its fixtures including explaining why they are vulnerable and to what extent or nature; provide general mitigation alternatives and identify any unresolved issues or gaps in knowledge; and,

vi to provide a basis for developing options for the future use, adaptation and care of the buildings, gardens, spaces and parkland in the immediate future and long-term, 10 years on.

1 .3 I DENTIFYING THE SITE

This Conservation Plan relates to the landscape and structures contained within the Registered Park and Garden of Raby Castle (Grade II*), and a small extension to encompass the Laundry to the north-west. Some components beyond this boundary will be discussed due to the current and historic relationships they hold to other elements within the Registered area. For clarity, references to the full extent of the estate will be referred to as Raby Estates, as will the client body. The physical structure of the castle will be referred to as Raby Castle. The study site for this Conservation Plan will be referred to as Raby Park when considering the full Registered area, or the Walled Gardens and stables when focusing on this smaller element. The definition ‘Raby Park’ is one that exists only for the purposes of this report.

07 SECTION 1.0

Contents

1.4 METHODOLOGY

A Conservation Plan is a document that aims to guide the future development and conservation of a heritage asset by setting out a framework for its management and maintenance in a series of policies which recognise the issues the building may face and also the opportunities where its heritage value can be enhanced. These recommendations, discussed in Section 6, are informed by the understanding and significance sections that come earlier on in the document.

The Conservation Plan will provide a resource for understanding the history, significance and potential for change at Raby Castle and Park. The principal sections of the Plan will encompass:

• Volume One, beginning with a background Understanding of the site and its setting; where it is and what it comprises. This section will also detail the relevant statutory designation applicable to the site, how it is used, and also character areas, key views, condition and archaeological potential.

• The Historical Development of the Park, Walled Gardens, and the stables area is summarised and set against the backdrop of the wider history of Raby Castle. This section brings together estate plans from Raby’s own archives as well as Ordnance Survey maps of the site to show the historical progression over the past three centuries, focusing on the Walled Gardens, and the Stable are.

• An Assessment Of Significance which will explain why and to what extent the site is important and valued, both culturally and with regards to its heritage. It is set within its national context.

• The Conservation Framework will provide as assessment of the issues as well as opportunities to enhance heritage value at Raby Castle and Park. This will include an analysis of the potential of the site for future change and recommedations to guide potential change in a sensitive and conservation-led approach.

• Volume Two contains a detailed Gazetteer of the wider Estate landscape areas and structures, and the Walled Garden and stables character areas and structures. Information on significance, historic development, issues, opportunities and potential are included.

08 PRELIMINARIES

MANAGEMENT GAZETTEERS CMP ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK Current Situation EVALUATION Past Evolution Challenges and Opportunities Significance Capacity and Parameters Landscape Character Areas Walled Gardens and Stables Character Areas Walled Gardens and Stables Character Areas Estate Structures Principles and Policies Action Plan VOLUME ONE VOLUME TWO Contents

1.5 R ESEARCH AND FINDINGS

An emerging research framework has been produced as part of this Conservation Plan to aid future research into specific details or components. This can be found in Section 6.3 Resources used, findings and any gaps in knowledge have been articulated here. The bibliography on page 127 sets out the sources used to inform understanding. Unless otherwise stated, all historic maps and plans are taken from the Raby Castle archives and remain the copyright of Raby Estates. Reproduction may only be carried out with thier express permission. Unless otherwise stated, photographs within the report are copyright Purcell.

1.6 C ONSULTATION, ADOPTION AND REVIEW

Internal and external consultation and advice on the content and direction of this Conservation Plan has been sought along two related strands of engagement. The first involved a series of client meetings together with frequent liaison with Durham County Council (also present at client meetings, site reviews and briefings) and Historic England (who were also provided with the original client brief for reference). A site visit was also carried out separately by Historic England to inform and assist the process. Feedback and steer arising from these activities was drawn upon to continually inform the plan’s development throughout the commission.

The second strand comprised the issue of a first and then second draft of the report, seeking more formal written feedback and advice from the client and key statutory stakeholders on the specific contents of the plan. To manage the efficient production of the report within the required timescales, drafts were issued for both internal and external review in parallel. Valuable comments and recommendations were received from all parties following draft one, issued by Purcell in July 2018. This information was assessed and absorbed to form draft two. Following further residual comments on draft two, a third and final version of the plan was created in September 2018, which now represents the present report. The status and content of this plan, which aligns with the original client brief, has been universally supported by the client, Durham County Council and Historic England. This now places any action arising from the report, including any masterplanning exercises, on a firm strategic foundation.

Following adoption of the Conservation Plan by Raby Estates, it is recommended that the documents are reviewed and updated on a regular basis, normally every five years or otherwise when significant change is proposed (whichever is sooner). This ensures that the content of the plan remains current and therefore of maximum benefit to those that seek to refer to it.

1.7 A UTHORSHIP AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This Conservation Plan has been prepared by Purcell, a firm of conservation architects and heritage consultants, on behalf of Lord and Lady Barnard. Specifically, it has been prepared by Rebecca Burrows, A ssociate, Dr Alexander Holton, Associate, Surveyor and Listed Property Consultant, and Bev Kerr, Heritage Consultant at Purcell, with contributions from Eleanor Houldcroft, Senior Landscape Architect at the L andscape Agency.

Purcell would like to thank a range of contributors who have assisted with the formation of this Conservation Management Plan. In particular Purcell would like to thank the assistance and of Lord and Lady Barnard, and members of Raby Estates team.

1.8 N AVIGATING THE DOCUMENT

This Conservation Plan has been produced to be read easily on-screen as a PDF. It contains a series of features that make it easier to use and navigate between the sections. The Contents button will take you to the contents page, from which you can navigate to any section. The Back button will take you to the previous page viewed.

References to specific components on a general plan or list will allow you to navigate to more detailed information on that component within this document and the Gazetteer.

09 PRELIMINARIES

Contents

UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

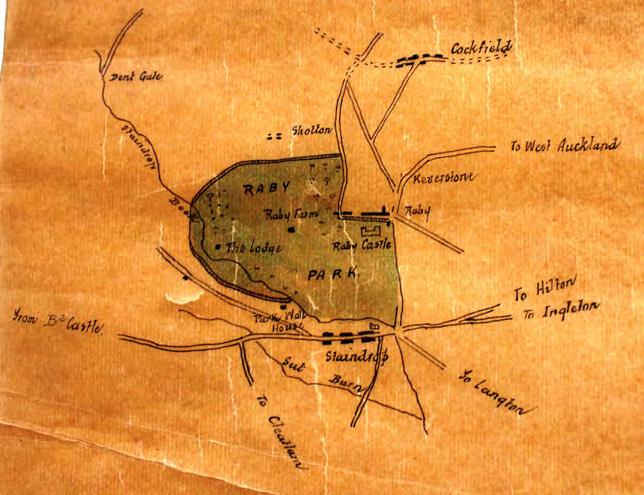

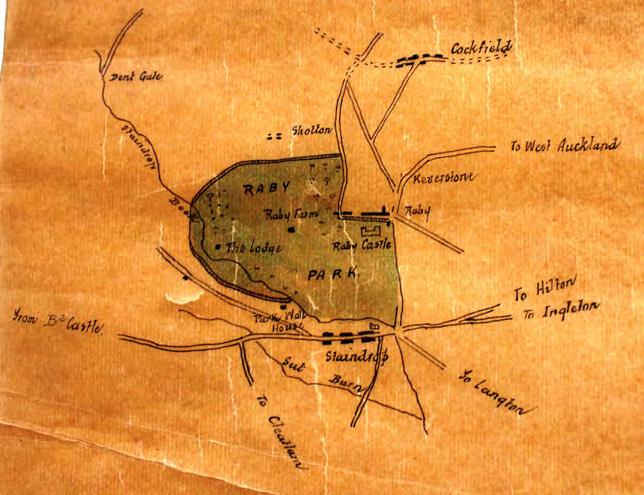

2.1 SI TE LOCATION

Raby Castle lies approximated 1km north of the village of Staindrop in County Durham. Bishop Auckland is located 11.27km to the north-east, Barnard Castle is approximately 9km to the south-west and Darlington lies c17.5km to the south-east.

Raby Castle and associated gardens sit within a parkland of approximately 101 hectares. Beyond this the full Estate covers large areas across County Durham and Teesdale. The northern boundary of the park is aligned with part of Burnt House Lane until it reaches the A688 at Keverstone Bank. The eastern boundary runs south along the A688 to Staindrop, where it turns and runs along the northern edge of the settlement. The western boundary of the park is defined by the edges of field boundaries, woodland and the line of water courses across the landscape, taking in features such as Bath Wood, Kennel Wood and The Laundry, before continuing north to re-join Burnt House Lane. The area Registered as a Park and Garden of special interest (Grade II*) is confined to a tight area of parkland around the Castle. This, and a small extension to encompass the Laundry is the study area and will be known as Raby Park within this report to avoid confusion with the wider estate and the castle as a structure. The definition ‘Raby Park’ is one that exists only for the purposes of this report.

10 SECTION 2.0

N

Location Plan 1: Wider map of area with Raby Castle circled

N

Locaton Plan 2: Showing the study area boundary. Base plan ©2018 Infoterra & Bluesky and 2018 Getmapping plc

STABLES THE

AUNDRY

STAINDROP A688 A688 BURNT HOUSES LANE Contents

WALLED GARDENS AND

L

RABY CA STLE

2.2 T OPOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY

The Raby Estate is within an area of Stainmore Formation which consists of mudstone, siltstone and sandstone which are overlain by glacial sediments.

The landscape surrounding Raby Castle is a gently undulating open landscape interspersed with tree stands and larger areas of woodland. The land rises from the Langley Beck which runs along the southern boundary of the Park on the edge of Staindrop, and gently climbs to the north and west. The Ponds within Raby Park were constructed in the mid-eighteenth century following the draining of the moat and lie within a shallow valley. The topography is such that views of the village of Staindrop from within the Park are extremely limited following antiquarian designers seeking to keep the commoners out of sight of the castle.

2.3 O WNERSHIP, MANAGEMENT AND USE

2.3.1 T HE ESTATE

Raby Castle and its associated Estate is the ancestral home of Lord Barnard. It is spread across Teesdale and County Durham and is a substantial agricultural estate which provides an important source of income. There are thousands of acres of arable, grazing and moorland and a large area of managed woodland. The Estate surrounding the Castle is managed from Home Farm in Raby Park but there are many other tenanted farms, residential houses and cottages in villages around Teesdale, including whitewashed farmsteads where families have been tenants for several generations. Home Farm is part of the national Countryside Stewardship Scheme where farming practices are modified to enhance flora and fauna on the lower Estate.

Raby Estates also generates income from the forestry and the sale of logs, property rental, shooting parties, filming, and game. Venison and Game, such as pheasant, grouse, and partridge are produced on the lower Raby Estate. The Raby Estate has been described as one of the best sporting estates in the country for its wild bird shoots.01 The Estate offers a low ground shoot within Raby Park. Currently the Estate offers shooting days for up to nine guns, including ammunition, transport and lunch.

Timber production is an on-going part of the Estates’ woodland management, with a mixture of hardwood and softwood milling timber being cut on a regular basis. The Estate now provides firewood to domestic and commercial customers and Christmas trees, grown on the Estates’ plantations are sold during December from the Christmas Shop at Raby Castle.

Conservation is an important focus for the Estate, the management of this is explained in more detail in Section 2.9.4. The Farm, Forestry and Game departments of the Estate all work in unison to ensure that land management practices balance conservation with agricultural objectives and standards.

The Raby Estate also employs a large team of craftsmen to develop and maintain properties and buildings across the Estate, including the gardeners serving the Walled Gardens.

2.3.2 T HE CASTLE AND VISITOR OPERATIONS

Raby Castle is open to visitors in the summer between 11am and 4.30pm. The Park, gardens and tearooms are open every day from 9am to 5pm. Following the death of the 11th Lord Barnard in 2016, Lord and L ady Barnard committed to making Raby Castle their home and to strengthen its viability and ties to the local and wider community. A new IT system has been implemented, with associated accounts and property management systems to increase efficiency.

In 2017 and 2018, the Estate has begun to open up the site to new visitors. The 2018 season is being used as a soft market test for understanding visitor numbers, dwell times and demographics. The opening times have been extended and the café has been refurbished for the 2018 season. Ticketed access has been moved from the entrance lodge to the stables and Walled Gardens area to allow visitors to use the tearooms without paying an entry fee. Ticketed entry is currently only for the Castle and Walled Gardens.

2.3.3 C URRENT USES

The Raby Estate has a variety of uses, from agriculture, forestry, conservation works, and shooting to tenanted properties, tours, walks and bike hire, tearooms, family activities, formal gardens, filming and special events.

Raby Park can be hired for corporate or public events such as musical concerts, country fairs, car rallies or product launches. Currently, the main annual events are car rallies, a Christmas market and flower shows.

In 2018, Royal wedding celebrations were held, along with a 10k race for Teesdale Athletics Club, and outdoor pop-up theatre events.

Raby Park provides over 200 acres of parkland for visitors to enjoy, but the majority walk in the immediate grounds around the Castle. Bike hire has recently been introduced and there are a number of unmarked trails around the ponds and Castle.

01 One of the “50 Best Sporting Estates” according to The Field (March, 2010)

11 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Contents

MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE AND REPORTING

TRUSTEES

Lord Inglewood

Sir Jocelyn Gore-Booth

DURHAM PROPERTIES

John Wallis/ GSC Raby Estate Marwood Estate UT Estate

LEISURE/ TOURISM

LORD AND LADY BARNARD

ADVISORY BOARD

CEO Duncan Peake

Duncan Peake Environmental Manorial Rights Minerals

Claire Jones Castle Opening Café Retail Events High Force Castle, Park & Gardens

Curator / Archives Security

SPORTING

John Wallis / GSC

Iain Alexander Raby Shoot Deer Management Andrew Hyslop Upper Teesdale Shoot

FORESTRY

Geoff Turnbull Woodland Management Estate Maintenance Firewood Christmas Trees

FARMING

Robert Sullivan / GSC

Raby Home Farm Sebastian Graff-Baker / Andersons

Raby Farm Shropshire

SHROPSHIRE ESTATE

Tom Birtles (Jul 2018)

FINANCE

Josie Graham

SERVICES

DEPTS

ESTATE WORKS Philip Dent OPERATIONS

Katrina Appleyard IT SUPPORT

To be Appointed

HUMAN RESOURCES

Katrina Appleyard/ HR2Day

HEALTH AND S AFETY Lycetts

12 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Contents

2.4 H ERITAGE PROTECTION AND DESIGNATIONS

2.4.1

S CHEDULED MONUMENTS

Scheduling derives its authority from the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act of 1979 and is the selection of nationally important archaeological sites.02 Despite its age and significance, Raby Castle is not a Scheduled Monument and there are no Scheduled Monuments within the site boundary.

2.4.2

L ISTED BUILDINGS

Listed buildings are structures of special architectural and historic interest which make up England’s historic environment. They are protected under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 and alterations or demolitions require Listed Building Consent from the local planning authority before they can proceed.

There are 24 listed buildings and structures which lie within the boundary of the site; within the stables and Walled Raby castle. Raby Castle and the listed buildings within the wider park are shown opposite and include:

01 Raby Castle, Grade I (1338625) 02 North gatehouse and attached Grade I (1338626) 03 The Folly, Grade II* (1121773) 04 North Lodges with North Grade II (133806) 05 Gas House, Grade II (1310898) 06 Temple, Grade II (1121784) 07 Bath House Cottage, Grade 08 Bath House, Grade II (1160046) 09 Footbridge, Grade II (1310742) 10 Boundary Stone, Grade II 11 Boundary Stone, Grade II 12 South Entrance Gateway (1338629)

02 Historic England: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/what-isdesignation/scheduled-monuments/ Last accessed 25/05/2018

13 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Registered Park and Garden Boundary of Raby Park (red), with a minor extension to the north-west (blue). The Walled Gardens are shown in green. Base plan ©2018 Infoterra & Bluesky and 2018 Getmapping plc N 01 06 11 02 07 12 03 08 04 09 05 10 Contents

The Walled Gardens and stables area contains the following Listed Buildings and their location is shown opposite:

01 Stables and Coach house with wall and mounting block, Grade II* (1121776)

02 Dutch barn, Grade II* (1121777)

03 Stable Block, Grade II (1310772)

04 Riding School, Grade II (1121778)

05 Hunting stables, Grade II (1160037)

06 Piers and Walls, Grade II (1121782)

07 Byre House, Grade II (1121779)

08 Former Cart House stables, Grade II (1310780)

09 Gardener’s House, Grade II (1121781)

10 Raby Park House and Butler Cottage and Outbuildings, Grade II, (1391549)

11 Cistern in Walled Garden, Grade II (1310785)

12 Garden Walls and Gateway with attached Fig House, Grade II (1121780)

The list descriptions have been reproduced within the appendix.

DESIGNATIONS: WALLED GARDENS AND STABLES AREA Walls Grade II* Grade II Non-designated Hardstanding Trees This plan is not to scale

EGISTERED PARKS AND GARDENS

Parks and Gardens of special istoric interest in England’ is managed by Historic over 1,600 sites which have particular significance, with n emphasis on ‘designed’ landscapes as opposed to mportance.03

consideration’ in the planning planning authorities must proposed development on he landscapes’ special character.

registered park and garden. The lies within the boundary of he registered area which is shown on the plan on page

03 Historic England: Registered Parks & Gardens: https:// historicengland.org.uk/listing/what-is-designation/registered-parksand-gardens/ [last accessed 4th June 2018]

14 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

03 02 04 01 08 07 06 05 12 11 12 12 12

10 Contents

N

09

2.5 O VERALL CONDITION

The Castle and listed estate properties are of a quinquennial survey. The most recent condition survey (QI) was carried out in May 2018 by Insall Associates. They have concluded that Castle continues to be maintained in a relatively condition. Within their report, they have recommended a number of works to the fabric which should be undertaken over the next five years. These redecoration of all joinery and metalwork of Castle and listed buildings, further repointing to the Moat Walls, refurbishment of a number of key apartments and rooms within the Castle, renewal of lead roofs to the Keep and South Range and Clifford’s Tower roof, renewal of the slate roof central Coach House building, restoration of House interiors and repairs to the North Wall of the Walled Garden, which continues to bulge at end.

The detailed condition of Raby Castle is outside scope of this report but further detail on the of the listed buildings within the Walled Garden Stable area are included within individual entries Gazetteer in Volume 2. The adjacent plan gives summary of condition of the buildings proposed focus of future development.

CONDITION: WALLED GARDENS AND STABLES A REA

Serious delapidation and redundant. works required Moderate delapidation and redundant/in ‘meanwhile’ use. Substantial repairs required Fair condition and redundant/in ‘meanwhile’ use. Repairs required Satisfactory condition and in use. Regular maintenance required

Note: Upper floors are generally unused relatively worse condition overall. This plan is not to scale

THE L AUNDRY

UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

N

Contents

2.6 C HARACTER AREAS

2.6.1 W IDER LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREAS

The following character areas are those considered in detail within the Gazetteer of Volume Two

16

UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

NORTH WOOD

INNER PARK

WALLED GARDEN

NORTH PASTURE

KENNEL WOOD

BATH WOOD

Contents

LADY CLOSE WOOD

17 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

The following structures are those considered in detail within the Gazetteer of Volume Two. 13L 12L 11L 9L and10L 8L 7L 6L 5L 4L 3 L 2L 1L WALLED GARDEN AND STABLES AREA NURSERY N 4L: KENNEL HOUSE AND WOOD NURSERY 2L: HOME FARM WALLED GARDEN AND STABLES AREA 3L: THE LAUNDRY 1L: CASTLE 5L: KENNEL WOOD COTTAGES Contents

2.7 B UILT HERITAGE COMPONENTS 2.7.1 R ABY PARK COMPONENTS

18 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK 13L 12L 11L 9L and10L 8L 7L 6L 5L 4L 3 L 2L 1L WALLED GARDEN AND STABLES AREA NURSERY N 6L: RABY HILL HOUSE 9L: BATH HOUSE 10L: BATH HOUSE COTTAGE 8L: SOUTH LODGE 13L: GAS HOUSE 11L: TEMPLE (BELVEDERE) 7L: NORTH LODGE 12L: NORTH WOOD FOLLY Contents

2.7.2 WALLED GARDENS AND STABLES CHARACTER AREAS

The adjacent plan sets out the six character areas of the Walled Garden and stables area, denoted by colour. The 20 sub-areas are shown on the following pages and considered in detail within the Gazetteer of Volume Two.

N

CHARACTER AREAS

Gardens Ancillary Gardens Stables Maintenance and Farmyard Residential Boundary Planting

This plan is not to scale

UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Contents

20 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

A: WALLED GARDEN (EAST)

D:

BOUNDARY TERRACE B: WALLED GARDEN (CENTRAL) Contents

C: WALLED GARDEN (WEST)

E: GARDENER'S HOUSE GARDEN

F: ANCILLARY ENCLOSURE (WEST)

21 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

L: FORMER WALLED GARDEN (NORTH)

M: RAFF YARD

J: AVENUE

I: HUNTING STABLES COURTYARD H: STABLES AND COACH HOUSE G: ANCILLARY ENCLOSURE (EAST)

K: RABY PARK HOUSE GARDEN Contents

N

22 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK Q: STABLE AND PIGGERIES

T:

COURTYARD

CAR PARKING

N Contents

P: STABLE YARD ACCESS SPINE O: OUTER RAFF YARD R: BOUNDARY PLANTING N: HAY BARN S: BYRE HOUSE GARDEN

2.7.3 WALLED GARDENS AND STABLES AREA

The following structures, both listed and unlisted, are those considered in detail in the Gazetteer of Volume Two.

23

UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

N

4S:

1S:

5S:

3S:

2S:

Contents

7S: DUTCH BARN C.300 METRES NORTH OF STABLES AND COACH HOUSE 6S: STABLE BLOCK NORTH-EST OF STABLES AND COACH HOUSE

CART

HORSE STABLES ATTACHED TO BYRE HOUSE

PIERS AND WALLS NORTH-EAST OF HUNTING STABLES

OUT-BUILDINGS

TO NORTH OF FORMER CART HORSE STABLES

BYRE HOUSE 8S: RIDING SCHOOL C.10 METRES NORTH OF STABLES AND COACH HOUSE 9S: STABLES AND COACH HOUSE, WITH WALL AND MOUNTING-BLOCK ATTACHED

THE HUNTING STABLES

24 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

15S:

13S: OUTBUILDINGS

STORAGE

12S:

14S: LEAN-TO

18S:

10S:

11S:

17S:

N Contents

16S: OUTBUILDINGS NORTH OF WALLED GARDEN

RAFF YARD HOUSE

AND

SHEDS TO NORTH-EAST OF RAFF HOUSE

FORMER SMITHY NORTH OF THE DUTCH BARN

SHED EAST OF RAFF HOUSE

BARNS TO NORTH OF GARDENER’S HOUSE

OUTBUILDINGS NORTH OF DUTCH BARN

OUTBUILDINGS TO REAR OF STABLE BLOCK NORTH-EAST OF COACH HOUSE

RABY PARK HOUSE AND BUTLER COTTAGE AND OUTBUILDINGS

25 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK 23S:

24S:

22S:

25S: OUTBUILDINGS AND GLAZED CANOPIES TO COACH HOUSE YARD 28S: COTTAGE

RAFF

26S: CISTERN IN WALLED GARDEN 27S: GARDEN

GATEWAY

FIG HOUSE 19S:

21S:

NORTH

20S:

N Contents

MODERN GLASSHOUSE

GARDEN SEAT TO SOUTH OF GARDEN WALL

OUTBUILDINGS

NORTH OF GARDEN WALL

TO

YARD

WALLS AND

WITH

GARDENER’S HOUSE IN WALLED GARDEN

OUTBUILDINGS AND GLASSHOUSE

AND SOUTH OF GARDEN WALLS

BARN ESTATE YARD

2.7.4 R ABY CASTLE OVERVIEW

The Manor of Rabi formed land belonging to Staindrop, given to the Prior of Durham by King Cnut in the 11th century. This suggests an early medieval presence on the site that was subsequently consumed by major and systematic medieval redevelopment. This culminated in the creation of the 14th century castle under the Nevill family, which still stands today.

The Nevill family lost control of Raby to the Crown following the failure of the Rising of the North in 1569. Sir Henry Vane the Elder acquired Raby from the Crown in 1626, forming the commencement of the line of succession to the present Lord Barnard.

In 1648, during the English Civil War, the castle was besieged, but is considered to have suffered little in the way of damage. The building was maintained in general terms until major alterations took place in the eighteenth century. Following an episode of family unrest (resulting in part of the medieval building being dismantled under the 1st Lord Barnard) a programme of restoration and improvement was put in hand by the 2nd Lord Barnard. This included major enhancements in the south and west ranges under the guidance of the acclaimed architect James Paine, forming opulent stately apartments and entertaining spaces. Under the instruction of Henry, 2nd Earl of Darlington, further work designed by John Carr was carried out on the castle, both inside and out, and around the estate. This included the carriageway in the main Entrance Hall and the creation of the round tower on the South Front. By the close of the eighteenth century major landscape improvement had been carried out, taking in the setting of the castle itself and the draining of the moat.

Further significant changes took place in the nineteenth century. From 1843 William Burn added to the South Front and created the Octagon Drawing Room. Further refinements were added in the 1890s under the 9th Lord Barnard. Thereafter, changes are considered to have been more modest, and concerned the ongoing operational and domestic functions of the Castle site.

Raby Castle has illustrative historic value as a perfected example of the lay medieval castle concept in the landscape, irrespective of its post-medieval changes and enhancements. Its developmental history from the medieval period to the twentieth century can be closely read, and it is a high-quality example of how medieval properties were upgraded and re-presented in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Illustrative value also lies in the plan form and treatment of the key spaces, enabling their historic functions and relationships to be understood and interpreted.

The Castle has powerful associative historic value for its focal and emblematic connection with Raby Estates and generations of the Nevill and Vane families. It also shares close associations with an array of innovators, designers and architects including James Paine and John Carr. A connection with the great medieval architect of the North, John Lleweyn, is also possible.

Raby Castle also has exceptional aesthetic value. Its setting in the designed landscape invokes a strong sense of the Picturesque, enhanced by its design language and use of local traditional materials. It is an imposing and captivating spectacle with the landscape designed and sculpted to form framed and dynamic views, experience and discovered by following the eighteenth century processional route from the South Lodge. The castle has communal value as the emblem of Raby and Staindrop, as a family home for generations, as a place of work, and as a place for the wider community to visit and enjoy.

The Castle is set upon a raised plinth of land, bordered by a dry moat and accessed via a gatehouse on the north-west corner. The Low and High Ponds, bridged by banked ground at their intersection, extend westward from the southern side of the moat edge. The Castle is built of local Carboniferous sandstone, with roof coverings of lead or slate. Irrespective of post-medieval improvements, the site is robustly medieval in its language and character.

The castle comprises a sequence of imposing blocks and towers, interlinked to form a series of continuous ranges set around a central courtyard, entered via the inner Nevill Gateway on the W side. Internally, a range of high quality period state rooms exist including the Entrance Hall, Baron’s Hall, Chapel, Dining Room, Library, Octagon Drawing Room, and Small Drawing Room. The Servants’ Hall and Kitchen are also of great

interest, the latter being 14th-century in date and most likely designed by John Lleweyn, the famous master mason of the Great Kitchen at Durham Cathedral. A network of bedroom, service and domestic spaces complete the historic room allocations within the castle, now either occupied by operations staff or serving as private accommodation.

26 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Contents

Raby Castle viewed from the south-west

2.7.5 WALLED GARDENS AND STABLES AREA OVERVIEW

The Walled Gardens within this complex include the three southern gardens and the northern garden within the walled/ha-ha area. These areas represent the spaces laid out as productive horticultural areas and pleasure grounds. The main walled gardens historically provided for the production of fruit and vegetable as well as an opportunity to display exotic plants to visitors. The spaces are characterised by their planting, with well-established trees and shrubs, areas of lawn and well-maintained beds. They are also compartmentalised by tall walls, providing security and areas for training plants.

Also within this area are the stables, the agricultural farm buildings and the maintenance and service areas of Raff Yard. The complex has three dwellings which are currently in residential use the Gardener's House, Byre House and Raby Park House. Historically, Raff Yard House was also a residential dwelling but is now vacant. Other areas include ancillary spaces serving the gardens, Duchess' Walk (avenue), the grassed area outside the southern wall, car parking and the northsouth spine road.

Stables

The stables relates to the equine accommodation for Raby Castle. This ranges from hunting stables for high-quality animals, through to carriage horses and cart horses. The associated coach house and motor car garaging complete this area, dedicated to transport and travel. The character of the area is one of hard surfaces and polite external exteriors of buildings, designed to be seen by visitors. The quality and use of the stables changes across the site, from the highest quality to the south near the Castle, moving northward along the spine road towards Raff Yard. The primary buildings are limewashed in pale yellow with white window and door surrounds, added to the group value of this significant ensemble. The riding school is a functional building of some rarity nationally that is linked to these uses.

Raff Yard and agricultural buildings

The Raff Yard has defined boundaries within two distinct courtyards the earlier Raff Yard and the outer courtyard associated with the hay barn. Raff Yard is a maintenance yard, containing the workshops and offices, associated with the supply, maintenance and upkeep of the Castle and Estate. The courtyard has evolved into the gardens of Raff Yard House. To the west, cart sheds and barns define the spaces in between them, which were originally hardstanding but have turned to grass. The hay barn dominates this area. The agricultural buildings link the polite stables to the functional maintenance yard to the rear and consist of cow byres and pigsties. Some were more architecturally detailed than others but all provided services to the Castle and family. The hay barn in particular holds significance and is a good example of the type nationally.

View from the Castle

The Walled Gardens sit on a gentle, southwards-facing slope c.100m north of the Castle. It is a rectangular, brick-walled enclosure with the back of an L-shaped stable range at the north-east corner and a serpentine south wall. A grassed border and walkway runs immediately south of this wall, separated from the park by a ha-ha with a stream running through it. A bridge with a parapet surmounted by cast-iron railings and a cast-iron gate on the park side crosses the haha and leads to a central entrance (listed Grade II with the garden walls) which was brought to the site from Shipbourne in Kent in the early twentieth century. 25m west of the entrance there is a fig house which replaced earlier buildings of the eighteenth and nineteenth century for a fig which is thought to have been planted in the eighteenth century. The walls on the south side were designed to be heated by flues and the original boiler house survives at the bottom of the Central Garden. The ha-ha runs around the west side of the garden and continues around the complex of stables and ancillary buildings which lie immediately north of the garden. The north and west sides of the enclosure are sheltered by trees.

Central Garden (character area B)

The central entrance leads to the central enclosure and a path flanked by clipped yew hedges. This runs north up the slope to a circular lily pond. The yew hedges continue northwards, as more mature specimens, flanking a lawn with geometric beds and a terrace which runs along the north side of the garden with a lead cistern dated 1746 (listed Grade II) set into the centre of the revetment wall. The terraced walk, from which there are views over the garden to the Castle standing in parkland to the south, continues eastwards through an arch cut into the hedge and leads to an enclosure formed by the hedge and wall dividing the garden from its eastern neighbour. A summerhouse, probably of 1930s or later date, is positioned against the north wall and stone steps lead down to a garden with clipped box hedges and a formal pattern of gravel walks. Plinths supporting urns of eighteenth century date are positioned at various points around this part of the garden. On the west side of the yew hedges the terraced walk continues westwards and there is a glasshouse positioned against the north wall.

Flanking gardens (character areas A and C) The gardens which flank the central walled compartment have lawns and borders. In the northwest corner of the west compartment (area C) there is a gardener’s house (listed Grade II) in the form of a Gothick cottage orné. In the south-east corner there is a small building with a chimney which is the boiler house for the fig house. The garden layout was largely created during the later twentieth century, following disruption during the Second World War for vegetable planting, incorporating pre-existing elements such as the yew hedges and central pool which are shown on the 1854-7 OS map.

Ancillary spaces

Immediately north of the Walled Gardens there is a walled enclosure with footings for glasshouses on the west side and a range of late twentieth century greenhouses on the east side. A gateway leads from the east end of the enclosure to the stables area.

The garden replaced one shown on a map of 1729 immediately south of the gatehouse.

Site Summary

Significance of the Walled gardens and stables area lies in its closeness to the Castle, in its functional connections and in the visibility of these areas, which were often hidden away by the eighteenth century. This may have been a matter of display, to showcase the exotic plants, but was also a response to the evolution of the location of the medieval village of Old Raby as it began to serve the Castle in a more formalised way. The area was developed in the late eighteenth century and remains an intact and well-organised area developed to provide ancillary functions to support the family and immediate Estate.

27 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Contents

2.8 S ETTING AND KEY VIEWS

2.8.1 SETTING

Raby Castle cannot be isolated from how it is experienced within its setting of the Registered park and garden, the wider historic estate. Designed and incidental views, and an understanding of the historic relationships between the Castle and the ancillary structures that served it, add to aesthetic and historical value. The landscape today can still be read to illustrate the medieval castle set within its enclosed deer park. It also illustrates the later Picturesque and Romantic landscape movements, with emphasis not on the military fortress, but on the polite south front and views from the carriage drive, which was diverted for this very purpose.

The Walled Gardens and stables are of interest for their close visual and functional relationship with the Castle. Early examples of walled gardens from the seventeenth or early eighteenth century could be areas of conspicuous display and highly visible, such as those at Auckland Castle, however as these became more common in the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century they were generally laid out away from the main house.04 At Raby Castle, the gardens remained visually dominant within the landscape, as although there were no views from principal rooms within the Castle (which all face south), the key view of the south elevation across the lakes also draws in the gently sloping walled gardens and stables. The reason for this location may have been a continuing matter of display, showcasing exotic plants, but was also a practical response to the evolution of the location of the medieval village of Old Raby and its field systems. The formalisation of the stable and farm functions serving the Castle and the sweeping away of the old village fits into a pattern of landscape change seen nationally. The functional and formal relationship of the walled garden area within the setting of the Castle remains highly significant and is relatively rare in terms of visibility, if not functionality.

Links between the powerful house at the heart of the Estate and the other structures that served it are both visual and physical. A key designed view from the Castle leads directly to Home Farm, which sustained the Estate. Key historic routes between the Castle and farm strengthen this setting and connections. Routes into the Estate have changed overtime, with the South, Middle and North Lodges all being the principal entrance at different periods in time. This changed in response to how the estate was used and perceived. connections are now less obvious. The link the use of the Bath House as a healthy and

pastime by those at the Castle is eroded through loss of garden features, planting, routes and the declining condition of the building itself. Few elements within the setting of the Castle make an actively negative contribution to setting, due to the relatively intact landscape surroundings. Improvements to dense modern planting and the requirement for succession planting of historic trees both have the potential to impact on setting. Modern road surfaces, car parking and the declining condition of some structures may also be considered as having a negative impact.

The setting of the Castle and the wider setting of the Registered landscape (views and experiences of drivers along Keverstone Bank for example) should be taken into account when proposing change that will sustain or enhance significance. The character areas identified in this Conservation Plan are of importance as elements of the Registered parkland but also as the setting within which the designated heritage assets are experienced.05

Each of the wider landscape and Walled Garden character areas are described in detail in the gazetteer and an understanding of these spaces should be used to manage change in a way that will sustain significance.

SETTING

Functional Formal Permeable north-south divide between the functional and formal

This plan is not to scale

04 https://content.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/ dlsg-garden-park-structures/heag108-garden-and-park-structureslsg.pdf

The immediate setting of the heritage assets within the Walled Gardens and stables area are defined by their historic (and to some extent, continued) uses from the formal to the functional.

05 Historic England, Conservation Principles, 2008

N

28 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Contents

2.8.2 W IDER LANDSCAPE KEY VIEWS

The designed parkland at Raby was developed during the eighteenth century in response to the evolving fashion for naturalistic landscape. The informal rolling parkland was designed with long winding drives from which to view the landscape, eye catching buildings and water, all linked by vistas and points from which to take in the prospect.

Key views include:

• Significant views looking towards the Castle from the parkland, in particular from the southern drive (views 1 and 5).

• Panoramic views on all sides of the castle, with long-distance views over the lakes and parkland to the south (views 2 and 4).

• Borrowed views east beyond the park due to the open character of the eastern boundary. These have partially been lost due to increased tree planting along the A688 (view 18).

• Long views west across parkland as far as Old Lodge. The Registered Park once formed the heart of a much larger parkland. These have been lost due to increased planting along the western boundary of the Registered Park, and conversion of parkland to farmland (views 6 and 19).

KEY VIEWS

Lost designed views

Surviving designed views

Dynamic views

Incidental views

Panoramic viewpoint

Lost views of wider parkland

This plan is not to scale

29 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

N 01 06 11 16 02 07 12 17 03 08 13 18 04 09 14 19 19 05 10 15 20

Contents

30 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK 01 02 03 04 05 Contents

31 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

06 07 08 09 Contents

Kennel Wood Cottage Home Farm Kennel House

32 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK 11 12 13 14 10 Contents

33 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK 16 17 18 19 15 20 Contents

2.8.3 WALLED GARDEN AND STABLES AREA KEY VIEWS

KEY VIEWS

Lost designed views Surviving designed views Dynamic views Incidental views Panoramic viewpoint 01 Panoramic designed view from Walled 02 Panoramic designed view from Walled 03 Panoramic designed view from Walled 04 Dynamic view from Walled Garden to Castle 05 Dynamic view towards the stables and house 06 Dynamic view towards the Castle 07 Incidental view across the car park 08 Dynamic view into the stable yard 09 Designed view along the avenue 10 Incidental view towards the hay barn 11 Incidental view towards the hunting stables 12 Incidental view towards the cart horse 13 Incidental view towards the hay barn 14 Incidental view from Raby Park House towards the Castle 15 Incidental view from the yard towards the Castle A View 4 (wider landscape) see page 29 This plan is not to scale

UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

08 13 07 06 12 10 05 11 01 09 14 02 15 03 04 A N Contents

2.9 LANDSCAPE

2.9.1 ECOLOGY/ARBORICULTURE

Woodland

The woodland found at Raby predominantly contains Beech with some Oak and Larch. The woodland was laid out in the mid-eighteenth century as landscaped parkland as well as for game cover. Younger woodland is primarily pockets of spruce plantation set within North Wood and Ladys Close Wood which are felled for timber crop. Christmas trees, grown on the Estates’ plantations are sold during December. Since the eighteenth century woodland cover has grown only slightly within the Raby Park however the overall woodland layout has remained similar.

Parkland Trees and Copses

Parkland tree species are primarily a mixture of Oak and Beech. There is a long history of parkland trees and clumps being planted, removed and in some cases replanted over the years for various reasons such as views and to commemorate special events, such as Royal visits, during the twentieth century. Clumps of significance include a small plantation to the west of the castle made in 1903 to commemorate the comingof-age of the Hon. H.C. Vane and a plantation from 1906 made on the drive from Staindrop to Raby which commemorates the Silver Wedding of the 9th Lord Barnard. Other trees planted commemorate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, visit of Queen Mary to Raby, visit of Princess Henry of Battenburg and the Queen of Spain, Coronation of King Edward VII.

The 10th Lord Barnard (d. 1964) was a keen forester and established new clumps and plantations. He replanted ancient clumps and replaced trees lost from the original landscaping plans.

The condition of parkland trees varies depending on age. Veteran trees within the Parkland may be hollow, with significant amounts of dead and decaying timber.

Ecology

The landscape contains a rich mosaic of habitats and numerous habitat corridors, thus providing the foundations of a very diverse ecology. These include running waters; ponds in bright sunshine and shady situations with varying levels of intervention. In addition, there are eroded bank-sides, grassy margins, as well as areas of damp grassland. The river and ponds are UK BAP (Biodiversity Action Plan) Priority Habitats. Wood pasture and parkland is a UK BAP Priority Habitat. Scrub within the woodlands also provides a vital nectar source for invertebrates.

35 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Contents

2.9.2 CONDITION STRUCTURE AND LANDSCAPE

Landscape Feature Condition

Access Routes and Car Park Main Parkland routes from North Lodge and access routes surrounding the Walled Gardens and stables area and Raby Castle are in fair condition. Access routes are in less favourable condition further from the main complex. The existing car park is informal with no road markings and worn grass edges.

Boundary treatments Ha-ha and estate railings are predominantly in good condition and appropriate in locations dictated by views and containment of livestock. Drainage problems associated with stone ha-ha’s within the wider parkland setting, some of which are in less favourable condition, particularly around Bath Wood. Walls along the southern and northern park boundaries appear to be well maintained.

Water Bodies (High Pond and Low Pond)

Play area and Cricket Pavilion

Both High and Low Pond appear to be well maintained aesthetically and are one of the most significant landscape features within the setting of Raby Castle. The water bodies have ecological value and are used by waterfowl as well as deer.

The play area is currently under utilised due to its peripheral location however there are excellent views of Raby Castle from the edge of the surrounding woodland.

Raby Castle cricket pitch is well maintained and greatly utilised by the public, again having spectacular views of the Castle. There is currently no formal access to the pavilion. An informal route along the neighbouring tree avenue appears to be used and could be improved.

Woodland Overall woodland management maintains the original intentions of the designed Parkland such as limiting certain views and providing game cover.

Accessibility in Bath Wood is currently limited, drainage and stand stability are an issue and scrub and rhododendron are encroaching on paths and structures such as the Ice House.

Open Parkland Pasture and Parkland Trees

Loss of parkland trees has contributed to a decline in the aesthetic value of the parkland. The angular edges of some tree clumps are inconsistent with the more rounded, natural form of the former parkland landscape. Current levels of stock grazing within the parkland maintains the sward to an appropriate height and species composition.

36 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Contents

2.9.3 CURRENT RELATIONSHIP OF LANDSCAPE TO S TRUCTURES

The subsidiary structures cottages, gardens, farms, etc.– all contribute to the overall significance of the landscape because they were and are essential to the operation and character of a great estate.

Landscape within Raby Park is currently heavily dictated by the condition and uses of buildings associated with the Estate. Building typology and their relationship with contextual landscape can be simplified into the three following categories: buildings accessible to the public and Estate staff; private buildings tenanted out; and structures at risk. These are visually depicted on page 42

Public

1 Buildings including the Castle, stables and structures within the walled garden can be characterised as follows:

o Strong visual relationships to the Wider Estate.

o L andscape is well maintained in view of these buildings.

o L andscape structure is generally simple and accessible.

o Materiality is of a high quality, able to withstand a high level of use.

Private

2 Buildings include South and West Lodge, Kennel House and Raby Hill House.

o Private dwellings have become domesticated over the years.

o Private gardens in the immediate context contain mixed planting and fencing.

o Differ in aesthetic qualities to buildings accessible to the public.

Risk

3 Buildings include The Bath House, The Gothic Pavilion, The Laundry, Gas House, The North Wood Folly, the Dutch barn & Raff House.

o A ssociated landscape setting has in most cases been lost due to lack of maintenance. This includes degradation of path networks and designed planting.

o A ssociated landscape is rarely used and lacks visual connectivity to the wider Estate setting due to vegetation overgrowth.

In addition to buildings, boundaries such as stone ha-ha's and walls within and enclosing the Parkland are significant structures used currently not only to manage deer but provide an important visual language to visitors to Raby Park in terms of accessibility. The use of ha-ha’s remains a strong characteristic of Raby Estate proposed in order to maintain views to the wider Parkland. Walls stretching the length of the Northern, southern and eastern extents of the Estate also provide distinctive bookends to the wider parkland.

37 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

Contents

PARKLAND ANALYSIS

Parkland Boundary

Stone Ha-Ha Stone Walls

Buildings accessible to the public and estate staff

Private buildings let to the estate staff. Structures at risk

N

38 UNDERSTANDING RABY PARK

This plan is not to scale Contents

HISTORIC TREE PLANTING

Lost trees since 1st edition 1860 New woodland / trees since 1st edition 1860 New woodland since Dixon Plan 1812 Modern field boundary dividing parkland

IGNIFICANT MODERN TREE CLUMPS

Vane Clump 02 Millennium Clump (Silver Jubilee of HM the Queen 1977) 03 Silver Wedding Clump 0 4 Park Clump

TARGET NOTES

A Informal tree planting along route now a formal avenue B Former avenue along the Terrace Walk now dense plantation C Lost tree clumps along the south side of the drive to West Lodge D Additional planting within the park to the north of Lady Close Wood planted by 3rd Earl of Darlington E Gothic Pavilion (referred to as the ‘Temple’ on the 1st edition OS map) This plan is not to scale

The major trees planted in the 18th century were recorded in a document entitled: “Trees planted about Raby”.

This lists planting carried out by Gilbert, 2nd Lord Barnard, 1727–1749 and was the first landscaping of Raby Park. It is not known who advised Lord Barnard, but it may have been James Paine. Major phases of planting include:

• 1727 The Elms below the bowling green near Low Pond

• 1740 Elms and beeches by the Bowling Green Road

• 1743 Great ha-ha, terraces, ditch and plantation made

• 1743 the deer park wall made

• 1743 The new or Great Pond made

• 1744 The bowling green, ha-ha terraces made

• 1748 Trees planted in the Alders

• 1748 Planting Trees at the Bath where the Oaks died

• 1746 Elms, Beeches next to George close in road to the Bath

• 1748 Young elms, beeches near the duck pond in the Alders

• 1749 Park wall made next the Turnpike road

39 UNDERSTANDING

RABY PARK Overlay of 1st edition OS map 1860 on current aerial. Base plan ©2018 Infoterra & Bluesky and 2018 Getmapping plc

S

01

Parkland tree

Parkland tree

3 4

2 North

Kennel

Bath

Lady

Sandy

E A

D

loss

loss

1

Wood

Wood The Terrace

Wood

Close Wood

Bank Wood

B C

N

Contents

2.9.4 WIDER LANDSCAPE INVESTIGATIONS Biodiversity And Natural Conservation

At the time of writing no ecological, biodiversity or arboricultural investigations have been carried out and no detailed assessment of the condition of the landscape has been made. It is anticipated further assessment and survey work will be carried out as options and development opportunities are explored.

The Raby Estate supports good conservation and there has been a focus on encouraging wild game and wildlife throughout the Estate. Advice has been sought from the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT) since 1991 and the Estate has implemented a rigid management policy to help encourage plant growth and wildlife.

Conservation headlands six metres wide have been introduced, which encourage the growth of broadleaf weeds and their associated insects, providing an abundance of food on which game bird chicks and small songbirds feed. The prevention of cleavers and barren brome invasion of cereal crops was achieved by the introduction of one metre sterile strips between field boundaries and headlands. This practice has contributed to Raby seeing some of the highest populations of grey partridge in some years.

To assist the grey partridge survival, plots of game cover mixture, incorporated with wild bird set-aside cropping, have been introduced to provide the partridge cover throughout the winter months, which helps reduce losses suffered from the talons of sparrow hawk. Within these plots it was noticed that large numbers of small seed gatting songbirds frequent these areas, which lead to a new project which was partially funded by GWCT and Kings Seeds. The three-year project was initiated to determine which crops suited song bird populations best. The project has encouraged a wide range of songbirds such as linnet, redpolls, goldfinches and skylarks.

Beyond the scope of the Raby Park boundary, Raby’s Upper Teesdale Estate is nationally and internationally known, both for its botany and ornithology. The Estate has UNESCO Geopark status. The plants assemblage is unique in Britain and the density and diversity of the birds probably the best in mainland Britain. In recognition of this, the majority of the Estate is a Site of Special, Scientific Interest (SSSI). Such is the quality of the habitat that much of the Estate is a Special Area of Conservation (SAC), and because of the density and diversity of birdlife it is also a Special Protection Area (SPA). This has resulted in Upper Teesdale being very popular with botanists and ornithologists alike.

Some of the Upper Teesdale Estate forms part of The Moorhouse and Upper Teesdale National Nature Reserve. The Estate has developed a working relationship with Natural England (NE) and in conjunction with NE and the tenant farmers, a number of conservation strategies are being implemented.

For example, the extensive moorland drainage system that was implemented after the Second World War in an effort to boost food production, led to quite severe erosion of the peat in places. Raby Estate, in conjunction with NE and the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) was the first in the country to reverse this damage by blocking all the open moorland drains. This was done to slow down erosion of the moor caused by carbon or peat being carried away with the draining water. It has proved to have been a complete success with the vast majority of the drains now having re-vegetated with sphagnum moss. These drain blocks, which create countless small pools, are beneficial to wading birds as a source of food and have also enhanced the capacity of the moor to act as a carbon sink, soaking up carbon which is deposited from the atmosphere.06

Woodland and Forestry

Woodland forms an integral part of Raby Estates, with a diverse mixture of broadleaf and coniferous plantations occupying land from the moorland edge to the lowland margins of the River Tees.