InnovatED

ALL OUT WAR: HOW MECHANICAL ENGINEERING IS CONTRIBUTING TO THE FIGHT AGAINST CANCER NOT EVERYTHING BELONGS IN A MUSEUM

VAHIDULLAH TAC | P. 2

JOHNATHAN KLICKER-WIECHMANN | P. 5

ARE YOU BEING WATCHED: IDENTIFYING SMART HOME DEVICE ACTIVITIES IN REAL-TIME TO DETECT THREATS

MALIN PREMATILAKE | P. 7

ROBOTS CARING FOR COWS: EXTENDING ROBOT NETWORKS TO ANIMAL AGRICULTURE

UPINDER KAUR | P. 10

DR. LINDA MASON

LETTER FROM THE DEAN

VAHIDULLAH TAC

ALL OUT WAR: HOW MECHANICAL ENGINEERING IS CONTRIBUTING TO THE FIGHT AGAINST CANCER

JOHNATHAN

KLICKER-WIECHMANN

NOT EVERYTHING BELONGS IN A MUSEUM

MALIN PREMATILAKE

ARE YOU BEING WATCHED: IDENTIFYING SMART HOME DEVICE ACTIVITIES IN REAL-TIME TO DETECT THREATS

UPINDER KAUR

ROBOTS CARING FOR COWS: EXTENDING ROBOT NETWORKS TO ANIMAL AGRICULTURE

TABLE OF

RACHEL ZHANG

ONE BIG BILL, OR A COUPLE OF SMALL BILLS? RESEARCHING CONSUMER REACTIONS TO HOTEL PRICING FORMATS

AMANI KHALIL

INCREASING AUTISM ACCESSIBILITY FOR FAMILIES OF COLOR

JOSE RAMON BECERRA VERA

IMPOSSIBLE TO ESCAPE: EXAMINING FACTORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO INDOOR AIR POLLUTION IN TOXIC ENVIRONMENTS

TYLER LEWIS

DATA IN DISGUISE: HOW INFORMATION

PRIVACY CAN BE PROTECTED WITH DIRECTED INFUSION OF DATA

RAZAK K. DWOMOH

THE DECLINE OF CIVIC EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES: EXAMINING

INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES IN-SERVICE

TEACHERS EMPLOY TO PREPARE THE NEXT GENERATION

LEANNE NIEFORTH

PTSD SERVICE DOGS MAY FOSTER RESILIENCE IN MILITARY FAMILIES

BOILERS WORK INTERNSHIP PROGRAM AWARD RECIPIENTS

A LETTER FROM THE DEAN

Dear Purdue Community,

It is no secret that graduate students are the bedrock of our great institution. They are the motor that drives our research mission, the force that propels our teaching mission – they are the embodiment of what it means to be a Boilermaker – persistent, innovative, driven, and resilient. That is why we do everything that we can to support our students during their time at Purdue, and that includes showcasing their research – again, and again, and again. Thus, we are proud to share with you the fourth edition of InnovatED Graduate Research magazine.

In this edition, you’ll learn how our world-class engineering program is making strides in the ght against cancer. When you think about Mechanical Engineering, cancer research doesn’t o en come to mind, but one graduate student will tactfully explain how he is working to improve the lives of those stricken by this terrible disease and create a better world. Another student will unveil some of the occupational hazards faced by historic preservationists and how his research can help protect them from serious diseases, like skin lesions, cardiovascular illness, and even cancer. If you have a smart device in your home, you won’t want to miss our third article, which touches on the real-life dangers that digital devices present, and how our student is working to protect the hundreds of thousands of people who use these devices daily. These are just a few of the amazing articles you’ll nd in the pages that follow, but there are so many more –all equally as impressive, thought-provoking, and inspirational.

I could not be prouder of the research conducted by our graduate students every day. Their dedication to solving today’s toughest challenges is truly inspiring, and I hope this magazine helps you better understand the value of graduate education to our community, nation, and world. With that being said, please enjoy the latest edition of InnovatED – a true testament to our graduate students’ persistent pursuit of the next giant leap!

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 1

ALL OUT WAR

HOW MECHANICAL ENGINEERING IS CONTRIBUTING TO

THE FIGHT AGAINST CANCER

BY: VAHIDULLAH TAC

Cancer is arguably one of the most painful experiences that a person can undergo. In 2022 alone, approximately 1.9 million new cases of cancer were diagnosed in the United States, according to the American Cancer Society. Be it through the physical toll of illness or the emotional trauma of witnessing a close relative su er from the disease, cancer destroys lives. Given this, it is no surprise that cancer research is a top priority of many scientists and research institutes. Cancer is a multidimensional problem, and vanquishing it requires simultaneous attacks from multiple fronts. This can include common treatments like chemotherapy, surgical tumor removal, and the

use of medications and vaccines. However, many people don’t consider the role mechanical engineering plays in the ght against cancer. For example, one of the most di cult experiences that a lot of cancer patients go through in their treatment is the surgery performed to remove cancerous tumors. During this surgery, a large part of skin surrounding the tumor must o en be removed, and the remaining skin must be stretched to cover any openings. Currently, the entire surgery, including decisions on where to cut and how much strain to apply to the skin, is all based on the personal

experience of the surgeon performing the surgery. Even if the surgeon is highly experienced, this can cause problems, as skin is

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 2

a material that has vastly di erent mechanical properties across di erent age groups, ethnicities, and sexes. To tackle this problem, we need advanced tools that can predict how a given patch of skin will react under loads. That is where mechanical engineering comes in!

At rst glance, mechanical engineering is an unlikely protagonist in this story. A er all, what do cars, airplanes, tractors, and other machinery have to do with surgery and skin? Well, a lot, as it turns out. A big part of mechanical engineering involves studying materials and how they respond to forces, the science of mechanics of materials. Mechanical engineers have spent the past several decades or even centuries developing tools devoted to studying the mechanics of materials. One such tool, the Finite Element Method (FEM), can be used to predict how any material in any shape or form will deform given a set of forces acting on the material. This tool is equally applicable to all kinds of materials. Some engineers use it to predict how the body of an airplane will deform under severe winds. Some use it to design packaging foam that deforms just

the right amount to minimize damage when cargo experiences sudden forces like being dropped on the ground. Others use FEM to predict how some metals like copper and aluminum expand permanently when subjected to extreme loads – a process known as plasticity, a curiously similar procedure to how skin grows when it is stretched for a long time.

You probably see where this is going –in the eyes of a mechanical engineer, like me, there is little di erence between aluminum and skin. Skin is a material a er all, albeit much so er and anisotropic (meaning it deforms di erently when stretched in di erent directions). So why not use all this knowledge that the eld of mechanical engineering has accumulated over centuries to model the behavior of skin? That is precisely what my research is trying to accomplish.

For the Finite Element Method (FEM) to work, we need highly exible material models that can accurately describe the behavior of skin. For the past year and a half, my research

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 3

Figure 1. Results of performing a virtual surgery on the scalp of a cancer patient. Contours of maximum principal stress during various stages of surgery (a) - (e), a photo of the scalp of the patient before the surgery (f), and a photo a er the surgery with the stress overlaid on top.

has focused on utilizing cutting-edge machine learning methods to develop state-of-the-art material models for skin. The material models we develop are designed from the bottom up so that they adhere to fundamental laws of physics and are usable in FEM. We used stress-stretch data obtained from pig skin to test the models and found that our models can accurately describe the behavior of skin – more so than ever before.

We use these successful models in FEM to perform a virtual surgery on the scalp of an actual cancer patient on a patient-speci c geometry. The geometry was obtained from the scalp of the patient using stereo photography. In the virtual surgery, we repeat the same process as was done in the physical surgery, and, as a result, the FEM simulation reveals locations of maximum stress concentration, which can aid signi cantly in planning future surgery operations.

We are very pleased with the performance of our models so far, and we are dedicated to improving them even further –

enabling the models to perform better under increasingly greater uncertainties. Cancer is a grave disease and ridding the world of it requires all we have got. I am proud to say that my work in mechanical engineering is contributing to society’s all-out war against cancer and creating better outcomes for those stricken by the disease.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

VAHIDULLAH

TAC

Vahidullah Tac is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Mechanical Engineering. He obtained his Master's and Bachelor's degrees from the Department of Aerospace Engineering at Middle East Technical University. His research focuses on applying machine learning to problems in mechanics. So far, in his Ph.D., he has worked on developing polyconvex material models for hyperelastic materials. Currently, he is working on developing nite viscoelasticity models that satisfy physics based criteria automatically.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 4

NOT EVERYTHING BELONGS

IN A MUSEUM

BY: JOHNATHAN KLICKER-WIECHMANN

Popular culture sets a thrilling expectation for those in historical preservation. Movies like Indiana Jones and Night at the Museum lead you to believe anthropologists, archeologists, and museum workers must be in peak physical shape to escape a charging T-Rex or evade a rolling boulder, at a moment's notice. While those particular hazards may be fantastical, unique and unseen dangers do threaten the health and safety of those who handle historical artifacts. These threats do not present themselves in as dramatic of a fashion as the classic boobytraps we have come to love in popular lms, but they can be just as dangerous and elusive to the naked eye. Most museum employees will not end up in a pit of venomous snakes during their lifetime. However, many will handle artifacts contaminated with chemicals equally as dangerous to the untrained professional. Prior to the 1980s, it was common practice to apply heavy metal powders, such as arsenic and

mercury, on organic artifacts as a means of controlling pests. This method was e ective at preserving animal furs and human remains, due to the highly toxic nature of the metals; However, exposure to heavy metals indiscriminately a ects humans and pests alike. Individuals who interact with contaminated artifacts are at risk of developing skin lesions, cancer, or destructive complications to their cardiovascular, muscular, digestive, and nervous systems. Even though the heavy metal pesticides were applied decades ago, they continue to pose a threat to current museum employees.

My research utilizes X-ray radiation to identify and quantify the presence of heavy metals in museum collections, allowing for the immediate identi cation of hazards. In this study, our team is utilizing X-ray uorescence (XRF), which involves the use of a focused beam of X-rays to characterize the molecular composition of an object. The radiation released causes the elements within a sample to emit a small amount of energy, which is then quanti ed by portable XRF technology. Every element has its own unique energy signature allowing us to determine if and which heavy metals are present on the artifact. When using this technique, it only takes seconds to determine if an

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 5

artifact poses serious harm to those working with or around it.

My work involves developing and shaping this approach, as well as continuing to collect more evidence that will strengthen the validity of XRF in this occupational setting. With evidence to support the viability of this approach, museum curators and other collectors will have a fast, easy, and non-invasive approach to identifying hazardous artifacts in their collections. This insight will allow professionals to better establish safety procedures for the handling and storing of artifacts. By providing collectors with an approach to identifying sources of heavy metals, we give them the ability to decide how to mitigate exposure. In practice, this could include requiring the use of personal protective equipment such as respirators and gloves when handling hazardous artifacts.

The ongoing success of this project is largely due to our multidisciplinary team, which also includes museum studies professionals. Their unique expertise in historical preservation techniques, including heavy metal application methods, was crucial

in my lab’s ability to optimize the e cacy of our approach. To date, this project has collaborated with Indiana University–Purdue University of Indianapolis’s Museum Studies Program, a prominent regional museum, an ornithology exhibit, and the FBI Art Crime Team. These partnerships have helped us to understand the unique demands of this non-traditional environment and improve our procedure. This experience and the data collected through these partnerships have allowed us to discover that some museum artifacts have unknowingly posed serious health concerns to employees and visitors for years.

With this research, I hope to bring awareness to the little-known dangers of historic preservation and help shape the future of health and safety in museums. I cannot promise that your favorite ctional archaeologist will trade in their whip for XRF equipment, but the long-term implications of this project could lead to the improved health and safety of hundreds of museum personnel.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JOHNATHAN KLICKER-WIECHMANN

Johnathan Klicker-Wiechmann is a master’s student in Purdue’s Occupational and Environmental Health Sciences Program, specializing in Industrial Hygiene. While advised by Dr. Jae Park, Johnathan has conducted research and presented ndings in the elds of aerosol science, exposure studies, and toxicology. Johnathan developed his love for research while pursuing his undergraduate degrees at Purdue. Working with Dr. Park on a bioaerosol project led Johnathan to pursue graduate school and additional research opportunities.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 6

ARE YOU BEINGED?

BY: MALIN PREMATILAKE

IDENTIFYING SMART HOME DEVICE ACTIVITIES IN REAL-TIME TO DETECT THREATS

When Alyssa, an 8-year-old girl from Mississippi, entered her room one evening to investigate strange sounds, she was unexpectedly greeted by a stranger’s voice. In moments, the stranger started screaming racial slurs at her, causing her to run in fear. While the voice Alyssa heard was very real, the stranger remained unseen. He accomplished this by hacking a smart camera in the room, which had a two-way talk service. Had he chosen, the stranger could have monitored Alyssa throughout the day without her knowing!

A smart home device, like the smart camera mentioned above, is a device with sensors and the data processing capability of a small computer, which can communicate over the internet. Some other common examples of smart home devices include smart speakers, smart switches, smart refrigerators and even baby monitors! These devices o er various valuable services that provide security, ease, and comfort. Due to the attractiveness of their services and the low cost, they have dramatically gained popularity in recent years. Studies forecast that over 29 billion such devices will connect to the internet by 2030, more than three times the number of smartphones, laptops, and computers combined.

However, smart home technology is still new and has caveats that need ironing out. As a result, unintentional vulnerabilities can exist in a device that perpetrators may take advantage of, resulting in incidents like Alyssa’s case. Many techniques have been proposed to improve smart home technology, but only minimal e ort is put into protecting user interests.

My research focuses on a framework called SafetyNet, which addresses this gap by introducing a novel technique that monitors smart home devices and identi es what each device does in real-time. When a device performs an activity (e.g., the smart camera is streaming), it sends/receives data over the internet. This ow of data is known as the network tra c of a device. SafetyNet analyzes the network tra c of each smart device in a home and noti es the users immediately when an activity is recognized. If necessary, users can block a suspicious device from further communication.

However, identifying an activity using network tra c is challenging. Raw network tra c consists of a stream of 0s and 1s without any activity-related information. Moreover, the

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 7

useful data (e.g., audio/video of a smart camera stream) is o en encrypted. Therefore, any attempt to read it can violate users’ privacy.

SafetyNet exploits a unique relationship between a device’s activities and its network tra c behavior to overcome these challenges. While analyzing network tra c data collected from several devices, we observed that the tra c ow of a device behaves in a particular manner when it performs an activity. Furthermore, this behavior is unique to each activity across all devices that perform it. For instance, when a user watches a smart camera’s feed from their smart phone, the camera sends a large amount of data to the user’s mobile phone over the internet. In contrast, a smart light switch receives only a small amount of data when it is switched on remotley through its

mobile app.

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that if we can recognize the unique activity behavior in a tra c ow, we can deduce the activity that generated it. To test our hypothesis, we set up a test smart home network in our lab, where 15 popular smart home devices are connected to a wireless home router. We created a program trained to detect activity-related behavior in a tra c ow and deployed it in the router. From the router, this program monitored and analyzed tra c ows of every smart home device in the network while they performed activities. It sent a noti cation to the user’s mobile phone upon detecting an activity.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 8

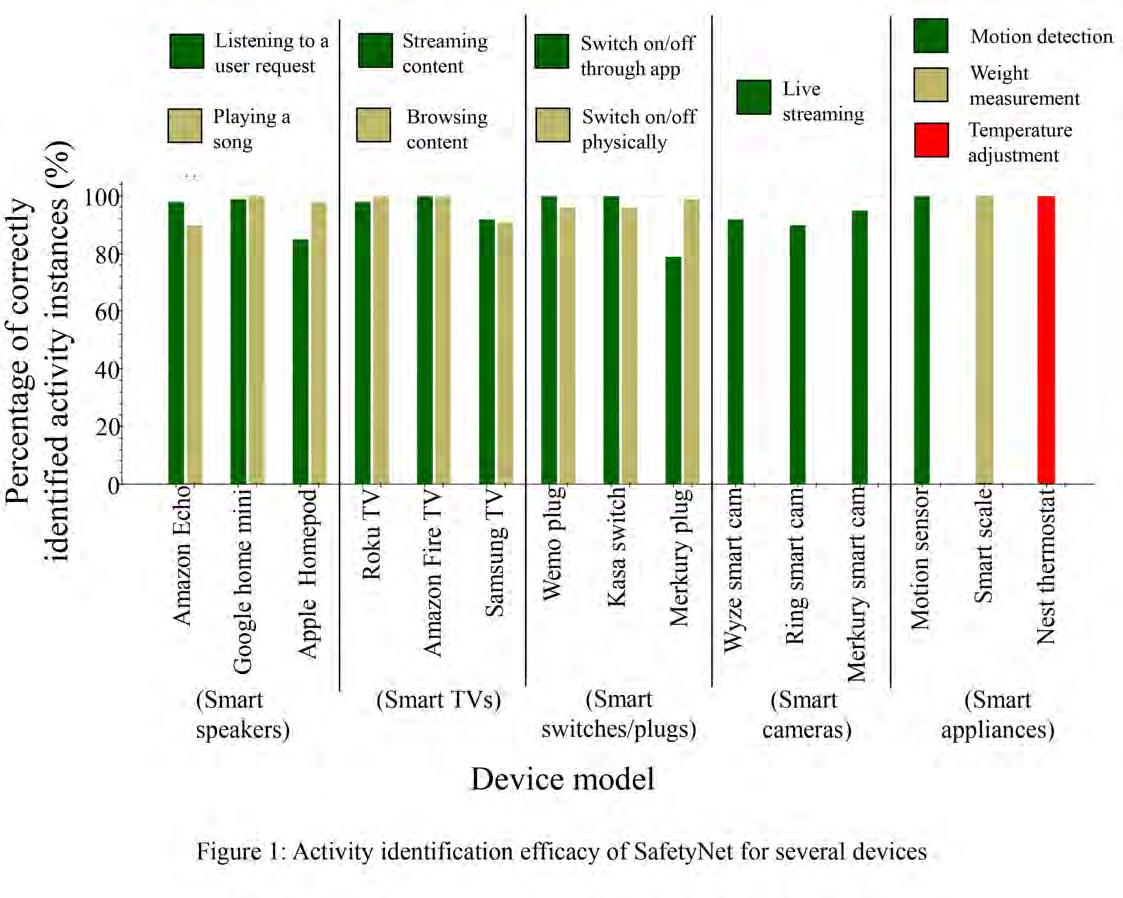

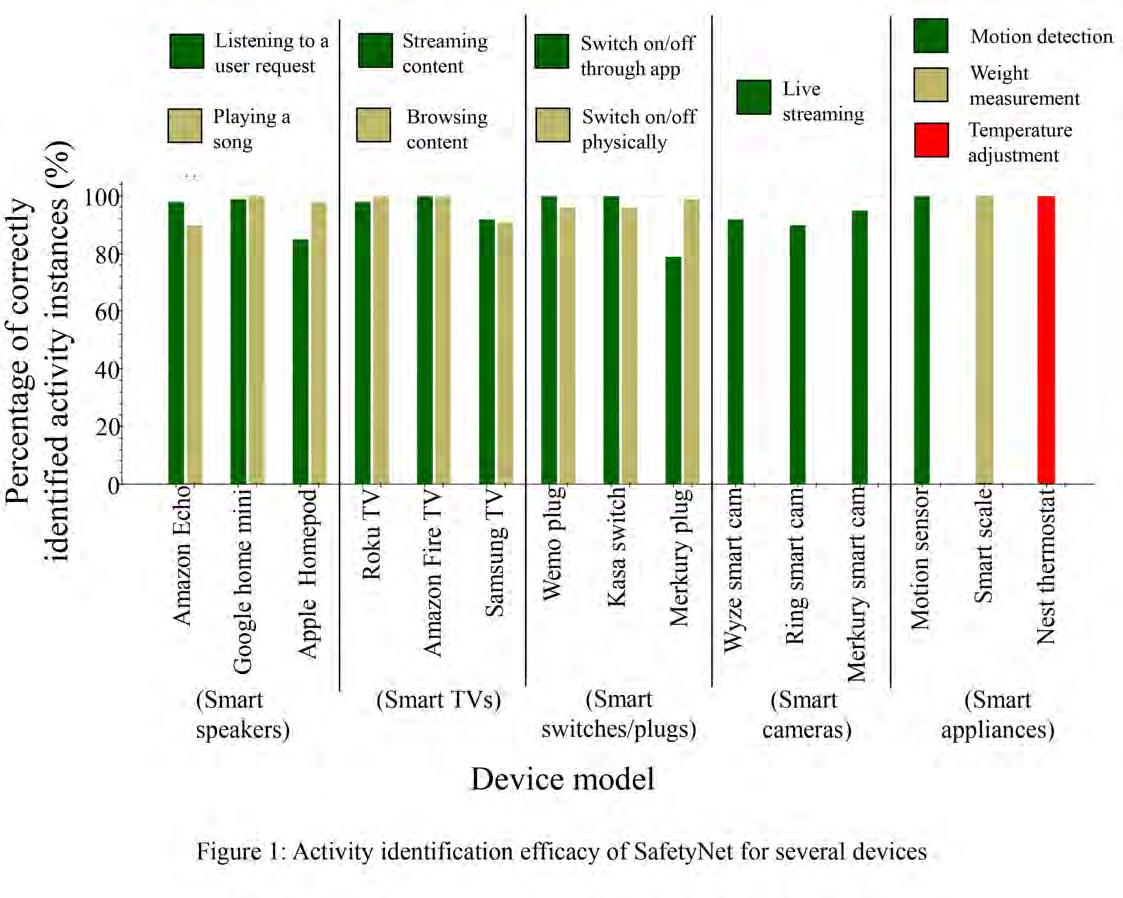

Figure 1 illustrates the identi cation

e cacy achieved by our program for each device. The accuracy is measured as the percentage of correctly identi ed instances of each activity against the number of times a device performed it. SafetyNet identi ed activities of all 15 devices with an average accuracy of 95.8%, validating our hypothesis. The high identi cation accuracy also demonstrates the suitability of SafetyNet for real-world applications. Interestingly, SafetyNet identi ed and noti ed the user within 8.3 seconds a er a device performed an activity. This speed is helpful in a scenario like before, where Alyssa’s parents would have been noti ed immediately that someone was accessing their smart camera. The results also show that SafetyNet can identify tra c ows of several devices, regardless of their make or model. Such a capability is quite important when considering SafetyNet’s real-world applicability. There are hundreds of di erent makes and models of smart home devices, so a good solution must identify the activities of most of them. SafetyNet shows a promising start towards achieving this. Moving forward, we plan to develop SafetyNet into a fully- edged home network security solution that can identify cyber-attacks

like malware. Right now, SafetyNet noti es users every time an activity is recognized. We plan to add a feature that allows SafetyNet to assess an activity’s safety before notifying. Smart home technology is becoming an essential part of our daily lives. Although still imperfect, it changes our lives for the better. Our work improves smart home technology's safety and security, so families like Alyssa's can have a safer and more enjoyable smart home experience.

PREMATILAKE ABOUT THE AUTHOR

MALIN

Malin Prematilake is a Ph.D. student in the Embedded Systems Lab at the Elmore Family School of Electrical and Computer Engineering. He works on developing new techniques to improve the security of the Internet of Things (IoT) with his supervisor, Professor Vijay Raghunathan. Prior to joining Purdue, Malin obtained his B.Sc. in engineering from the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. He enjoys playing Volleyball and spending time with his family during his free time.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 9

EXTENDING ROBOT NETWORKS TO ANIMAL AGRICULTURE

BY: UPINDER KAUR

Imagine yourself on a dairy farm; what do you see? A herd of cows — Joey, Bessie, and their friends — happily chewing cud while hanging out. The farmer oversees milking and looks for signs of discomfort among individual animals. The caregivers closely monitor each animal and know which cow prefers what food. While this was a reality a few decades ago, this idyllic representation of a farm is no longer accurate. With over 5,000 heads of cattle even on moderate family farms, one-on-one caregiving is impractical and, in most cases, impossible. Instead, farmers must now use automated systems to manage the herd, which deliver the same treatment to all animals with few allowances for individual needs. Although necessary to operate at such large scales, these systems lack provisions to adapt to the needs of individual cows, resulting in discomfort and late detection of diseases. Ultimately, all this results in poor quality of life for the animals, which also impacts their productivity.

With expected global population growth, the demand for dairy products is increasing. Shrinking resources, climate change, and labor shortages further add to the problem, making it di cult for farmers to sustain their businesses. Recent research has shown that improving animal

welfare improves the farm’s productivity as happier cows produce more and better milk. While individualized care yields improved welfare of animals, implementing such customizations is an open challenge as technology for animal agriculture is still limited.

My research aims to reestablish individualized care for dairy cows by leveraging a network of rumen-dwelling robots called RumenBots to monitor each animal continuously. The rumen (cow’s stomach) controls the health and productivity of a cow. It is a large fermentation tank wherein microbes break down plant matter into energy. The rumen is a constantly churning, highly strati ed environment with gases on top, freshly eaten hay in the middle, and a clear uid at the bottom. Current study methods either involve manual sampling or static sensors placed at the bottom of the rumen. Both o er a limited view of the rumen’s inner workings. A better understanding of the rumen will help develop superior and customizable nutrition plans that maximize productivity, health, and overall welfare. Therefore, the RumenBot is equipped with sensors measuring the acidity (pH),

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 10

temperature, ammonia, and methane concentration, providing a complete view of the biomarkers in the rumen.

Using the RumenBot, scientists, for the rst time, can study the rumen for long periods continuously. We are developing a novel buoyancy-based system that enables the RumenBot to move in an ultra-low power mode. A critical aspect of building this robot is knowing where the robot is in the rumen. Localizing the RumenBot helps associate measured parameters to the three-dimensional volume, which helps identify sites of critical changes in biomarker activity. My research shows that sound waves can localize the RumenBot safely. By combining sound waves with motion sensors, I can track the robot in the simulated rumen with an error of less than 2cm.

For continuous monitoring, the data sensed by the RumenBot needs to reach the farmer as soon as possible. Hence, I am building a wireless network connecting the herd with a central cloud. The network works in two stages: rst, the RumenBot communicates data from inside the body to a collar around the animal’s neck. My research helped characterize the propagation of radio-frequency (RF) waves from inside the body to the outside, identifying 400-433MHz as the most appropriate RF band for this purpose. I chose a low-power and long-range protocol to establish the communication link at 433MHz between the RumenBot and the collar. At the collar, I implemented algorithms that extract information from the raw sensor data to reduce the tra c in the overall network.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 11

Processing the data at the collar enables the system to quickly identify critical events, such as heat or calving, which need immediate human intervention.

Currently, I am building the second stage of the robot network that ties each collar to a central cloud. A centralized cloud will host information about the entire farm, making it easy for farmers to monitor everything from a single location. Cows are sentient beings that move around unpredictably; therefore, I am building a mesh-like network wherein all collars are interconnected. The challenge is optimizing the routing protocols for maximum coverage without a dense deployment of routers to optimize for cost and coverage tradeo s. At the cloud, nutrition and welfare models process the collected data to identify the needs of each animal and decide their food and care.

My research aims to build a better world for animals in agriculture, wherein they are cared for as individuals. Formalizing an end-to-end system that adapts to the changing needs of the animals will help reduce the burdens of the farmer without compromising on animal welfare. This new technology is customizable to other

domains in animal agriculture, allowing widespread use. Meeting the food security goals while improving animal welfare necessitates systems that put animals rst.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

UPINDER KAUR

Upinder Kaur is a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Engineering Technology, under the guidance of Dr. Richard Voyles. She is also the lab manager of the Collaborative Robotics Lab (CRL), where she mentors multiple graduate and undergraduate students. Upinder works on extending the reach of robots with the help of cyber-physical systems and arti cial intelligence to solve real-world challenges in food security, animal welfare, and climate change. In her free time, she enjoys exercising, painting, and tending to her vegetable garden.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 12

ONE BIG BILL OR A

COUPLE OF SMALL

BILLS?

RESEARCHING CONSUMER REACTIONS TO HOTEL PRICING FORMATS

BY: RACHEL ZHANG

Imagine that you and some friends are planning a trip over spring break. You look at hotels in Cancun and the prices are within your budget. So, you proceed to the booking stage and are ready to pay – but wait… what is this random “resort fee”? Plus, a cleaning fee? And 20% taxes? Well, this just became annoying… These consumer complaints are the motivation behind my research. Under the direction of my Ph.D. advisor, Dr. Hugo Tang, I research how consumers react to di erent pricing formats. Speci cally, I want to know how hotel consumers feel about prices that are broken into the main price and additional fees, and how hotels should present the fees in a less irritating way. First, we explored why hotels choose to show the room price and additional fees separately. According to economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, both Nobel Prize Winners, people tend to focus on the major component and ignore

the minor parts when processing multiple-piece information. Just think about those $19.99 price tags you see at the grocery store – people might take a quick look at the 1 in the tenth digit, think the price is ten-ish dollars, and feel that it is a good deal. Applying the same logic, you might also see a hotel room for $200/ night (with $30 taxes and a $50 resort fee), and you might have the impression that the room costs “two hundred-ish dollars.” Hotels and online travel agencies use this psychological bias, the anchor and adjust e ect, to encourage more bookings. However, we found that separating prices could actually turn consumers away. According to another Nobel Prize winner, Richard Thaler, people hate losing money, especially when they are losing multiple times. So, if the room price and fees are presented separately, consumers might feel as

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 13

if they are paying for the room price… then taxes… then a resort fee… This feeling of paying multiple times is more discouraging than seeing a higher total price at the beginning without surprises.

So, between the “$0.99 phenomenon” and “I don’t want to pay three times”, who is right? Our research found that both are valid but under di erent conditions. For online hotel booking, the feeling of losing multiple times is stronger than the joy of nding a “good deal.” This is for three reasons. First, hotel fees are higher on average than the smaller fees associated with everyday shopping (sales tax and shipping), so they are harder to ignore. Second, the law requires that hotels and online booking websites show additional fees in a very obvious manner, so a room price of font size 20 with a resort fee of font size 6 will get into trouble. Furthermore, hotel rooms (let’s say for a night in Cancun) feel less familiar than a cup of co ee, so consumers are more attentive when reviewing the hotel prices and are, therefore, less likely to ignore the additional fees. With all this in mind, it is clear that hotel managers should be upfront and show the total price, as they do for airlines.

We also found that how consumers feel about prices changes depending on how close their trip is to the time they book their hotel. People tend to be speci c and practical when something feels close, time-wise, location-wise, etc. Therefore, when you are booking a trip for the near future (i.e., tomorrow), your brain becomes more detail-oriented and scrutinizes each item at the checkout. Thus, for trips that will take place in the near future, consumers dislike seeing prices and fees separately and are less likely to ignore things. However, when a trip is far away (i.e., a year from now), you would only focus on abstract feelings about this trip, such as the atmosphere and general feelings about the hotel room. In this case, you focus less on the price itself and are more likely to feel that the prices are cheap when seeing the room price and fees separately.

Since it is still industry practice to show the room price and fees separately, we tested a few things managers can do to lessen consumers’ negative reactions. One technique that hotels frequently use is free cancellation. Even if you hate the feeling of

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 14

being exploited multiple times, free cancellation so ens your heart and makes the commitment of booking less scary. Another thing a hotel can do is allow consumers to delay payment until check-in, which also reduces the pressure of booking. We found that free cancellation always works, regardless of whether the trip is days, weeks, or months in the future, but late payment attracts only travelers who plan trips far in advance. Since leisure travelers usually book their trips further ahead than business travelers (who have a less exible schedule), hotels can consider using a exible cancellation policy and later paying time to encourage booking.

Behavior economists, like me, aim to combine fuzzy consumer psychology and logical economics to provide the market with a better product. In this case, that product is hotel rooms. So, my advice to you is to be extra cautious about prices when booking your next trip – the glittering waters of paradise might cost you an extra thousand pennies.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

RACHEL ZHANG

Rachel Zhang is a Ph.D. student at the School of Hospitality and Tourism Management under the guidance of Dr. Hugo Tang. She is also pursuing a concurrent Master of Science degree in Agricultural Economics. Rachel's research areas include hotel revenue management, demand forecasting, and spatial econometrics. She serves as the current Vice O cer of Diversity at Purdue Graduate Student Government, and an Educational Ambassador at the Center for Advocacy, Response, and Education (CARE) to support survivors of interpersonal violence. Rachel would like to thank Ayrielle Espinosa for her valuable suggestions on this article.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 15

IMPOSSIBLE TO ESCAPE:

EXAMINING FACTORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO INDOOR AIR POLLUTION IN TOXIC ENVIRONMENTS

BY: JOSE RAMON BECERRA VERA

Climate change increases the threat of wild re smoke and ground-level ozone in places like Southern California, forcing people indoors in search of fresh air – but for some families, the interior of their home might be just as dangerous. In a recent ethnographic study, I investigated the social elements that contribute to indoor air pollution within a residence in Southern California's Inland Empire.

Through my observations, I found that social relationships among people, microbes, pets, pests, and even cleaning supplies co-create toxic indoor atmospheric environments.

For the summers of 2021 and 2022, I traveled to Southern California's Inland Empire

(IE) to collect eld data related to outdoor air pollution. The IE is a region that shares a notoriously polluted air basin with Los Angeles County but consistently ranks lower in air quality. The concentration of toxic air in the IE is linked to the global logistics industry and an increasing number of wild re smoke events. The IE is home to one of the country's largest distribution centers, with a growing cluster of warehouses in the region used to store, repackage, and move commodities to the rest of the country by diesel trucks, trains, and aircra , contaminating the local environment. The region is also home to mountains and hills surrounding the metropolitan landscape in the IE. Climate change, colonial re suppression

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 16

policies and management, and urban growth into these re-prone ecosystems have all contributed to a rise in local wild re smoke occurrences over the past few decades.

During wild re peak seasons, the toxic combination of transportation and wild re pollution proliferates the outdoor air in the IE, making the inside of homes one of the few places that people think are safe from the hazardous air. As a eld researcher, I saw plumes of smoke up in the mountains while stuck in tra c next to diesel trucks making the air hazy. When I went inside to measure particulate matter with my GeoAir2 monitor (Park et al. 2021), I was surprised to see that pollution levels were sometimes higher indoors despite closed doors and windows. A er realizing that the evaporative cooler (a device designed to cool the air in a home) was introducing a lot of particulates inside the home, I quickly became curious about what other things could be contributing to indoor air pollution.

As an anthropologist, I am trained to examine how social relationships a ect environmental phenomena, so I delve into an observational study indoors to document how

chemicals, smoke, and other things became suspended in the air. Houses and other buildings are built with materials that host a range of microorganisms in the air in uencing our health (Dunn et al. 2013), and researchers found that social practices like hygiene regimes also introduce synthetic chemicals, shaping micro-species relationships in homes (Wake eld-Rann, Fam, and Stewart 2020). Building on this research, I focused on the multi-scale social relationships contributing to toxic air inside of homes.

Echoing researchers like Rachel Wake eld-Rann et al., I found that hygienic practices, like mopping, wiping down countertops, and getting rid of pests introduced synthetic chemicals into the home, but the social dimensions of pollution did not stop there. I identi ed two other overarching themes contributing to indoor pollution. First, the household understands critters like ants, lizards, and ies as signs of uncleanliness –warranting pesticide attacks if spotted indoors.

During the hot seasons in the IE, residents expect an abundance of critters around their homes. However, cultural and social notions of

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 17

critters as threats to indoor cleanliness and health, drive people to spray pesticides in houses and repeat hygiene regimes more o en, using a variety of cleaning products – all of which have mixtures of chemicals harmful to people’s health.

Second, daily indoor routines like cooking, lighting candles, spraying scents, and even playing with dogs that travel from outside to inside introduced smoke, more chemicals, dust, and pet dander into the air. Not only did these social dimensions of daily life in the region introduce pollutants into the air, but they also a ected each other. For example, dogs eating food indoors might attract critters searching for a quick meal, triggering pesticide sprays that come with an unpleasant smell, and, to reduce the stink, people spray aerosol scents or light candles – compounding the micro-species and triggering chemical mixtures they might breathe.

Amidst climate change causing intense wild res, and the growing warehouse hub bringing in more pollution to the region, a common recommendation to avoid unhealthy

air is for people to spend more time indoors. However, spending time indoors may not provide people with the healthy reprieve that they require. Smoke introduced by cooling machines, pets, pest control, and cleaning and hygiene solutions all contribute to indoor pollution that may be just as hazardous to their health. In the short term, we must ensure that residents in pollution-prone areas understand the hazards that can contribute to creating an unhealthy environment indoors; however, moving forward, it is critical that we examine the political and economic power structures that make pollution unavoidable for individuals both inside and outside of buildings.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jose R. Becerra Vera is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Anthropology, working with the Farmer Learning, Agriculture, Culture, Humanities, and Social science laboratory. Jose’s doctoral research uses a mixed-method ethnographic approach to examine the political ecology of transportation pollution and wild re smoke, and uneven exposure to atmospheric contamination. More broadly, his research interests include slow violence, environmental justice, exposure studies, and historical political ecology.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 18

JOSE R. BECERRA VERA

AUTISM ACCESSIBILITY INCREASING FOR FAMILIES OF COLOR

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental and social communication disorder diagnosed in about 1 in 44 children in the United States.

Early identi cation and intervention of autism services are crucial; however, services are o en less accessible for families of color, causing children to miss out on the known bene ts of early interventions. Angered that my clients of color were missing out on these bene ts, I was motivated to seek out the barriers preventing racial-minority families from accessing appropriate services. There are two categories of symptoms associated

BY: AMANI KHALIL

communicating, and emotional reciprocity. The second category of symptoms includes restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviors (RRBs). RRB symptoms include repetitive motor movements, insistence on routines, restricted patterns of interest, and hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input. Autism is a spectrum disorder, meaning symptoms and severity signi cantly vary from person to person.

Typically, an autism diagnosis is given in childhood as symptoms must be present then. O en pediatricians will give toddler parents questionnaires during a check-up to screen for autism.

with Autism. The rst includes symptoms in social communication, including di culty understanding and maintaining relationships,

The pediatrician will then decide if a referral to a child psychologist or further testing is needed. During testing, a psychologist will

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 19

Photo Caption: Amani, at her clinical practicum at Easterseals Crossroads, preparing an ADOS-2, an assessment tool used to diagnose autism.

more closely examine a child’s social communication skills through various assessments. During assessments, a psychologist will o en use an assessment tool to play with the child and observe their social interactions with them and their caregiver.

As a child psychologist in training, the inspiration behind my research originated from my clinical work conducting autism evaluations at Easterseals Crossroads and Riley Hospital for Children. During my clinical placements, I noticed how racial minority children who displayed what were apparent symptoms of autism were o en referred to my clinic much later than their White peers. I was heartbroken seeing these children not referred sooner, which delayed their autism diagnosis and access to critical services.

We know that early identi cation and intervention of autism services are crucial. Research suggests early interventions for children with autism as young as 24 months can increase social, language, and cognitive performance. Parents play the most critical role in early help-seeking and intervention for children with autism, thus providing one necessary means to address the racial disparity. Unfortunately, getting a diagnosis of autism is even

more delayed for racial minority families. To address disparities, my research team and I conducted a study identifying the barriers for racial-minority families accessing autism interventions. First, we conducted a systematic literature review of the help-seeking obstacles that racial-minority families face in accessing autism interventions. Together we searched through all prior research studies on what racial-minority parents perceived as barriers to getting an autism diagnosis and subsequent treatment.

Our results identi ed four common help-seeking barriers racial-minority families experienced in accessing autism interventions. Barriers included: structural barriers, provider competence, Autism literacy, and cultural stigma.

(1) Structural Healthcare barriers describe the logistic and language barriers racial-ethnic minority families encounter in accessing autism services. For example, families in our studies described challenges such as having a language barrier communicating with their child’s healthcare

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 20

provider, expensive services, and being far away.

(2) Provider competence is another concern that parents cited as a barrier deterring them from seeking help. For example, parents felt that their pediatrician didn’t make a referral early enough, felt that their provider was discriminating against them due to their race, or didn’t trust their provider.

(3) Autism literacy refers to racial-minority families’ lack of knowledge regarding what autism is and isn’t. This also includes when, where, and how to access autism-related services.

(4) Cultural stigma refers to negative cultural attitudes regarding developmental disabilities. This barrier refers to how negative bias towards autism and disability o en increases a family’s isolation and delays the family from seeking the diagnostic label of autism.

So, how do we make autism services more accessible? From our results in identifying barriers to getting an autism diagnosis, there are steps our community can take to help reduce autism stigma. Much of what many people know of autism is from the media. Many media representations of autism show TV and movie characters as White, highly intelligent, and male. We know from our ndings that cultural stigma is a barrier to

identifying signs of autism. Pushing for more representation of diverse individuals with autism in the media may help to represent autism across ethnicities and gender.

To address cultural stigma continuing to educate diverse families on a variety of symptoms and signs of autism can help. In addition, we recommend that providing awareness and signs of autism to parents through daycares, a erschool programs, and religious centers can help to raise autism awareness.

Lastly, as psychologists, we hope to help educate primary care providers on the signs and symptoms of autism. This can help providers better identify children who may need a referral for an autism evaluation.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amani is a Ph.D. candidate in Counseling Psychology. Amani's research interests broadly pertain to health disparities in neurodevelopmental disorders and minoritized parent experiences. Amani has completed clinical practicums through Riley Hospital for Children and at Easterseals Crossroads, a disability non-pro t. Amani conducts neurodevelopmental assessments such as autism testing and therapy with children and families in these settings. Additionally, Amani is currently the student director for the Purdue Counseling and Guidance Center (PCGC), the Counseling Psychology program's in-house training facility where students begin psychotherapy training. Amani has also served as a student representative for the Purdue Autism Research Center (PARC).

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 21

AMANI KHALIL

DA TA IN DISGUISE

HOW INFORMATION PRIVACY CAN BE PROTECTED WITH DIRECTED INFUSION OF DATA

BY: TYLER LEWIS

Do you like spies? Those elusive and suave men and women that work in the shadows à la James Bond. The job of a spy is relatively simple on paper: covertly monitor enemy activities and protect their own nation’s secrets. However, spies and their agencies operate under a principle of “trust but verify,” taking measures to ensure neither party double-crosses the other while relaying intelligence information about clandestine operations to each other. Analogously, industries operate under the same motto when sharing data with researchers. Industries must disguise or ‘mask’ the identity of their data for fear of reverse engineering and data leaks, which

could be disastrous to their reputation and competitive advantage.

O en in modern industrial systems, the need for data sharing arises out of arti cial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) techniques that rely on processing vast amounts of data. For example, a nuclear power plant may capture terabytes of data, all of which can be leveraged toward AI/ML applications such as automated operation, condition monitoring, and development of future designs. However, they may seek out collaboration with specialized researchers to analyze the data and provide business

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 22

insights. But how do companies or individuals protect their information? More speci cally, how can the two entities work together while ensuring there is no risk of information misuse?

Just like a well-trained spy, they cannot simply provide their data without a suitable disguise. To protect the proprietary aspects of their data, the operators of a nuclear power plant o en ‘mask’ their data before handing it to researchers, which is unmasked upon reception. But is the data truly protected? Existing masking techniques like encryption protect the data from a malicious third party during transmission, but not from the researchers themselves. The enforcement of non-disclosure agreements and bureaucratic red tape provides some protection, but cannot guarantee that the researcher will hold up their end of the deal; in fact, they have a signi cant incentive to sell the data to an adversary which may dissuade collaboration resulting in the company forgoing the bene ts of AI/ML.

My research, directed infusion of data (DIOD), focuses on answering this question with a novel technique allowing the plant operators to

directly hand masked data to a researcher, who can analyze it in the same manner as they otherwise would with the original data. One major application for my research is to provide privacy to energy industries to enable the nationwide push toward renewable energy and net-zero carbon emission by 2050. Among industry and academia, many groups aim to deploy hybrid energy systems to achieve this lo y goal, but data privacy concerns undertaken during collaboration remain detrimental to this long-term goal and exacerbate future climate challenges. Secure collaboration is not only an e cient business transaction, but an active contributor toward national, or even global, technological advancement.

DIOD alleviates any concerns about data security by removing the proprietary aspects of the data using well-established physics-based techniques and masking it by using the physics of a di erent generic system. DIOD permanently changes the type of data given to the researchers; if the power plant operators need to analyze data from the sensors of the

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 23

nuclear reactor, DIOD may transform the data into audio les given to the researchers without loss of information, thereby allowing the operators to reap the full bene ts of the analysis without changing their goals and methods. In this case, not only will a third party fail to recover the original data, but any attempts to guess the identity of the data leads to the original audio source instead of the reactor. By providing this ‘perfect disguise’ for the data, researchers can analyze its masked form with no loss in the quality of analysis, and no third-party –researcher or otherwise – will ever be able to reverse-engineer the proprietary aspects of the data. For example, during analysis, the researchers may identify that o -key notes in a Taylor Swi song correspond to anomalies in the temperature and power sensors of the nuclear reactor core.

In essence, DIOD alleviates the privacy concerns of industries while maintaining the quality of analysis for the researchers, enabling and accelerating the adoption of technological advancements such as hybrid energy systems,

smart industry, and cutting-edge medical procedures. So, the next time you are listening to your favorite Taylor Swi album, ask yourself: could this music secretly convey information from a nuclear power plant?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

TYLER LEWIS

Tyler Lewis is a 1st year master’s student in the School of Nuclear Engineering. His work with advisor, Dr. Hany Abdel-Khalik, revolves around applications of data science and cybersecurity targeted toward energy systems. A er completing his B.S.N.E. in May 2022, also in Nuclear Engineering at Purdue, Tyler began his graduate career in June 2022 and has authored journal publications, given presentations, and worked with various national labs. In his free time, Tyler enjoys reading short novels and researching stocks. Over the past year, Tyler has worked alongside various colleagues to research and implement DIOD, including an undergraduate research assistant named Chloe Yoder. Chloe is a 3rd year undergraduate student in the School of Nuclear Engineering.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 24

THE DECLINE OF CIVIC EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES

EXAMINING INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES IN-SERVICE TEACHERS EMPLOY TO PREPARE THE NEXT GENERATION

BY: RAZAK KWAME DWOMOH

Civic education plays an indispensable role in addressing societal needs for the public good. However, Americans’ basic knowledge about civics and government is declining. The lack of civic education prevalent in the U.S. is leaving young learners (K-12 students) uninformed and disengaged, which could prove concerning for the future of U.S. democracy. My research aims to examine the impact of civic education on young learners and the instructional strategies that in-service teachers employ to prepare young learners to be civic-ready. There is a signi cant decline in young people’s civic knowledge and civic engagement in the U.S. For example, the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania conducted a survey in 2016 and found that there is a decline in Americans’ knowledge about the branches of government, with 26% of Americans able to mention the U.S. branches of government as compared to the year 2011, where 38% of Americans were able to name all the three branches of government (the executive, legislative, and judicial) (Annenberg Public Policy Center, 2016). Thus, within ve years (2011-2016), there was a signi cant drop of twelve percent of Americans who could mention the three branches of government. Additionally, the newly developed

Educating for American Democracy (EAD) (2021) Framework reveals that the U.S. Federal Government spends more on students in STEM elds (approximately $50 per student) annually than on civics (approximately $0.05 per student). The disparity in federal funding for students in STEM elds and Civics is a great concern for developing civic-ready individuals in their youth to champion and preserve the U.S. democracy for future generations.

Moreover, research examining how di erent schools are equipped with civic learning opportunities, practices, availability, and access to resources for students is limited (Wol & Rogers, 2019). As a result, I decided to delve deeper into the instructional approaches and resources that foster civic readiness at the secondary levels as my research trajectory for my doctoral degree here at Purdue. Kelly (2008) de nes civic readiness as a child’s preparedness to participate in the community “in ways that are bene cial and acceptable to the civic culture of the community” (p. 55).

Brennan and Railey (2017) also de ne civic readiness as an individual’s acquisition of knowledge, skills, and disposition needed in becoming an active and informed member of

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 25

the community a er graduating from high school (Brennan & Railey, 2017). Kelly (2008) points out that “civic readiness is as important for young children as school readiness and as vital as literacy skills to advance through formal education” (p. 55). Children who display civic readiness “present a beginning range of skills and prosocial attributes (political e cacy, community attachment, as well as empathy, social and institutional trust, agreeableness)” (Kelly, 2008, p. 56). Kelly opines that these skills and prosocial attributes help reinforce children’s social engagement and problem-solving skills. Civic readiness equally fosters student learning and increases the graduation rate in K-12 schools (Prentice & Robinson, 2010). This research is signi cant because middle grade is a pivotal transitional stage for young people where they form ideologies and perceptions about themselves, others, their communities, and the world around them.

I employed the case study design to investigate in-service teachers’ perceptions and instructional strategies they use to prepare young learners to be civic-ready. The participants were seven social studies teachers (four 7th-grade

teachers and three 8th-grade teachers) from a midwestern middle school in the U.S. I used teacher interviews (14 interview datasets), extensive class observation hours (over 75 hours), content analysis (over 260 documents including syllabus, curriculum maps, textbooks, trade books, class artifacts, students’ workbook, students’ assignment sheets, students’ drawings/paintings, posters, and videos), and eld notes to triangulate the data and to ensure its credibility. This project is part of my overarching doctoral dissertation, so the preliminary ndings show that instructional strategies, such as teaching current events and incorporating them into lessons [e.g., the CNN 10 video—world news explained within ten minutes), role-plays, simulations, and teaching transferable skills (e.g., communicating appropriately, debating without being argumentative, punctuality, timeliness, working on deadlines) among others do foster the civic readiness of middle graders. As pragmatic and purposeful approaches to preparing young people to be civic-ready, in-service teachers view these

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 26

instructional strategies as signi cant contributions to fostering the civic readiness of young people, creating an informed and participatory citizenry, and developing civically competent individuals to solve the proliferating societal and national problems in the U.S. and our contemporary world.

In conclusion, to develop civic-ready individuals, we need a collective e ort and responsibility. We can help young people develop civic readiness and undertake civic actions when we (parents, teachers, and educators) collectively identify and address the challenges to young peoples’ civic readiness and provide them with the needed support, resources, and instructional sca olding that foster civic readiness. It is my hope that the ndings of this study bene t education policymakers in enacting policies that bolster K-12 civics education and improve middle graders’ academic success and civic readiness, thereby cultivating a new generation of leaders to champion democracy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Razak K. Dwomoh is pursuing his Ph.D. in Curriculum and Instruction with a focus on Social Studies Education at Purdue University. His research interest is in preparing young people to be critical thinkers, problem-solve, and be civic-ready. He investigates students’ civic readiness, inquiry approaches in teaching and learning, culturally sustaining pedagogies, historical (mis)representations in trade books and textbooks, and diversity, equity, and social justice issues in education. Razak was also one of the Graduate School’s 2022 Boilers Work internship recipients. Learn more about his internship experience on page 31.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 27

RAZAK K. DWOMOH

RESILIENCE IN MILITARY FAMILIES

BY: LEANNE NIEFORTH

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) a ects about ¼ of post 9/11/01 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans [1]. Families of these veterans may experience challenges post-deployment including mental health concerns, physical health concerns, and issues with family functioning. Essentially, PTSD a ects the entire military family; however, families are o en le out of research focused on PTSD interventions. One such potential PTSD intervention, that has been minimally explored in the context of the military family, is a psychiatric service dog. Psychiatric service dogs are trained to do speci c tasks that mitigate speci c symptoms of veterans’ PTSD. For example, they might alert veterans to anxiety by nudging the veteran’s leg or might interrupt nightmares by waking the veteran. The purpose of this study was to investigate and explore the ways in which PTSD service dogs might contribute to building resilience in military families post-deployment. We recruited participants from K9s For Warriors, a national nonpro t service dog

organization that provides PTSD service dogs free of charge to veterans. A total of 67 veterans and 34 spouses answered eight open-ended survey questions regarding having a service dog in their home as part of a larger study. The questions included: (1) What is the most helpful aspect of having a service dog? (2) What does the service dog do that helps the most? (3) What are the drawbacks of having a service dog? (4) How has the service dog positively impacted your children? (5) How has the service dog negatively impacted your children? (6) How has the service dog positively impacted your spouse? (7) How has the service dog negatively impacted your spouse? (8) Is there anything else you would like to share about your service dog?

We analyzed responses using the constant comparative method. This qualitative analysis method employed best practices to ensure rigor of ndings. First, multiple members of the research team read through the data multiple times to note categories that

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 28 PTSD SERVICE DOGS MAY FOSTER

emerged from the data. These categories were grouped into codes and then those codes were grouped into larger themes. Throughout this process, members of the research team met multiple times to discuss the data, the emerging categories, and larger themes. Once theoretical saturation was attained (i.e., there was no more new information) the researchers used a well-established theory, the theory of resilience and relational load [2], as a framework to interpret the data. Three major themes emerged from this qualitative process.

The rst theme to emerge was that service dogs help military families to build emotional reserves. By ful lling their trained role to mitigate PTSD symptoms, service dogs boost resources for veterans and their spouses. The experience of having a dog helps veterans to recalibrate stressors and regulate emotions that in turn a ects the resources available to relationships. One veteran described the in uence of the service dog’s trained task on emotional resources, saying “He gets in my lap to help with anxiety, and he interrupts me to bring awareness to myself and my surroundings.”

The second theme to emerge was that service dogs increase relational load in military families. The addition of a service dog to the home increases the demands on the household. Service dogs require time, money, and everyday care. Both veterans and spouses discuss this load, but the spouses describe it more frequently and o en in the frame of caregiver burden. Additionally, family relationships can be disrupted by service dogs as they may bring on jealousy or disrupt intimacy by ‘always being there.’ One veteran described, “My service dog takes a lot of my time. This is potential time that could be shared with my spouse.”

The third theme to emerge was that service dogs facilitate relational maintenance among military families. Service dogs were consistently described to serve military families beyond their trained role. They aided in communication processes, emotional regulation among family members, and fostered a sense of togetherness that facilitated relational maintenance strategies. In many cases, the service dog was considered a part of the family. One spouse shared, “My husband’s

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 29

service dog is one of the family and we love him like he is human.”

Findings from this study suggest that service dogs promote a resilience process in military families by helping to build emotional reserves, increasing relational load, and facilitating relational maintenance. Future studies should explore the potential implementation of a family-focused education program provided during service dog training programs to promote and re ne this process of resilience.

Note: Veteran and service dog names have been replaced with “my service dog” and “my husband” to protect anonymity.

You can learn more about this research at: Nieforth, L. O., Craig, E. A., Behmer, V. A., MacDermid Wadsworth, S., & O’Haire, M. E. (2021). PTSD service dogs foster resilience among veterans and military families. Current Psychology, 1-14.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

LEANNE NIEFORTH

Leanne is currently a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Arizona College of Veterinary Medicine. She earned her Ph.D. in Human-Animal Interaction at Purdue University, and both her MS (Communication) and her BS (Animal Science) at North Carolina State University. Her research focuses on discovering the science behind human-animal interaction. She is passionate about understanding how we can partner with animals to create interventions for individuals who have experienced trauma.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 30

BOILERS WORK INTERNSHIP PROGRAM

The Boilers Work internship program provides ten graduate students per year with a $7,500 stipend to pursue an unpaid summer internship. This program is intended to help our students garner real-world work experience, re ne so -skills, and establish career connections prior to graduation. Below are the experiences of ve Boilers Work interns.

RAZAK K. DWOMOH

I am Razak Dwomoh, a doctoral candidate in Curriculum and Instruction at Purdue University. My research interest intersects inquiry teaching, civic readiness, culturally sustaining pedagogies, diversity, equity, and social justice issues. I pursued the Boilers Work Internship to gain the awareness and practice of the academic, behavioral, and social/emotional systems of support for middle graders from diverse backgrounds; receive mentorship and professional experience; network with professionals and shadow meetings in student success.

My career goals include being a tenured

professor, researcher, and teacher educator. To forward these goals, the Boilers Work Internship allowed me to work with the Lafayette School Corporation district director of Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) and the Assistant Principal of Tecumseh Junior High School. First, the Assistant Principal mentored me in (1) gaining practical experience in providing support to at-risk and struggling students and (2) students’ academic and SEL, as middle graders navigate the struggles of middle school. He enrolled me in the Conscious Discipline (CD) Academy—a weeklong training by the Tippecanoe School Corporation (TSC) for teachers across Indiana. I networked with diverse educators, acquired resources, and learned about CD and SEL. I received a certi cate of completion from TSC in Student Success. I applied what I learned about the three brain states (survival state, emotional state, executive state) to create a lesson plan for Tecumseh’s Developing Responsible Inspirational People program, which empowers students to become positive ambassadors in the school

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 31

and the community.

The knowledge and skills I acquired will aid my future career as an educator in fostering SEL and Student Success in K-12 education and teacher preparation. This training was signi cant because, despite being an instructor for some years, I focused more on content and pedagogical content knowledge. I am improving as a teacher educator by paying attention to my students’ SEL needs, especially during the post-Covid era. I am re ecting on my teaching approaches to prioritize SEL in classroom instruction, directly or indirectly, and further research into how SEL of social studies pre-service teachers and teacher preparation training contribute to e ective student teaching experiences in K-12 settings.

My second favorite experience in the summer internship was participating in the HEART Camp. This was a week-long, hands-on, fun, and engaging program where students learned about SEL and the three brain states. I worked with 64 students and 15 teachers across ve schools. That helped me develop so skills such as leadership, problem-solving, and teamwork. The students participated in activities, such as drum circles, brain cap, and art exploration—where ve graduate students led by a teacher from IUPUI Herron School of Art and Design, developed and led art exploration for SEL and practiced art therapy leadership skills with the students. The students made artifacts and drawings of a happy face, a sad face, and a “mad” face, depicting their SEL and the three brain states. During the last day of camp, we visited the Children’s Theraplay in Carmel to meet the beautiful horses.

This internship shaped my perspective of career expectations as a teacher educator and built the right network for my career. It helped me develop teacher empathy for young learners and good communication and interpersonal relationship with diverse teachers, students, and superintendents. I foresee myself applying intentionality in preparing pre-service teachers to foster student success and SEL in social studies classrooms. I recommend the Boilers Work Internship to every student who intends to acquire real-world work experience, re ne so skills, and establish career networks before graduation.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Razak K. Dwomoh is pursuing his Ph.D. in Curriculum and Instruction with a focus on Social Studies Education at Purdue University. His research interest is in preparing young people to be critical thinkers, problem-solve, and be civic-ready.

ANTONIA SUSNJAR

As a rising 4th year Ph.D. candidate in Biomedical Engineering, doing an internship was an imperative to help me decide what career path I will take on next. Furthermore, it was a puzzle piece missing in my training. During my undergraduate studies, I was a research fellow working on cancer therapeutics development. I enjoyed applying what I learned in my courses to pharmaceutical applications. A er completing my undergraduate degree in Biochemistry and Cell & Molecular Biology, I got a job as a research assistant at the Houston Methodist Research Institute in the Department of Nanomedicine. During my time there, I developed implantable

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 32

medical devices for the controlled and sustainable release of cancer immunotherapeutics. While this work was very rewarding, I wanted to learn more about diagnostics and early prevention. My doctorate work at Purdue University is focusing on imaging and diagnostics of neurotrauma. Being emerged in various research projects such as magnetic resonance imaging hardware development, sequence optimization, and clinical pilot studies, I o en wondered if my skills would be useful in real-life applications. The Boilers Work Internship at MED Institute was an amazing opportunity to learn new skills and apply my theoretical knowledge to the clinical hurdles of large medical device and pharmaceutical companies. Our work has helped them further their product to the market or clinic, reaching millions of people. Furthermore, it has helped me realize that I do have the skills required to enter the workforce and that the training I have received has prepared me to systemically approach a problem and work toward the solution. However, as it is well known, the academic environment is very much di erent from the industry environment. While both are highly competitive, at MED Institute we worked as a team toward a common goal. It took some time for me to go from a one-person team to a larger team. I enjoyed team comraderies, and it was extremely e cient and enjoyable tackling problems together. My role was very uid but always well-de ned. My mentor at the MED Institute was outstanding, and there was never a con ict or criticism directed toward me or any of my team members. I think the reason for this is the exceptional communication that was implemented in every task. Whenever a client had questions or complaints, we all communicated solutions in a professional manner. Not only was communication inside the team outstanding, but the whole company was also welcoming and inclusive. On my rst day, everyone came by my o ce to introduce themselves and welcome me to the team - from the CEO to lab technicians. This was truly special. A er my time there, I was o ered a part-time position that could result in a full-time position once I graduate. However, due to a few

changes in my research studies, I could not accept the part-time position that was o ered. I am hoping that with my graduation approaching, and the professional relationships I built during my time at MED Institute, I will have an opportunity to continue my career there. There were so many memorable experiences, and it is hard to di erentiate just one. I enjoyed meeting clients from world-leading companies for medical devices and having a casual conversation with them, as well as solving how to image small beroptic threads using MRI scanner. I would highly recommend the Boilers Work Internship Program to every graduate student no matter what career path they want to take.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 33

Antonia Susnjar is a Ph.D. candidate and Graduate Research Assistant in the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering (BME). She received the Geddes Fellowship (2019) and the Bottor Fellowship (2020-2021).

ANTHONY OKAFOR

Prior to graduate school, a signi cant part of my professional experience included working on the editorial team of a literary and arts journal called Praxis Magazine Online. I worked remotely and served as poetry chapbooks editor from the spring of 2016 until the fall of 2020 when I began my MFA in Creative Writing at Purdue University. My duties included preparing calls for submission, si ing through chapbook submissions, selecting, proofreading, and formatting manuscripts for publication, while corresponding with forthcoming authors on feedback, cover design, and other such itineraries.

This experience was pivotal in my decision to pursue an internship at The Nation in the summer of 2022 through the Boilers Work Internship Award. My intention was to work for a literary organization that ampli ed experimental voices from marginalized and/or international communities. At The Nation, I worked under the Assistant Poetry Editor and read submissions for the magazine, created CMS content for the poetry website, and managed social media content for the Nation Poetry. Learning the CMS content was the most useful part of the internship. It was a totally new skill to me, while many of my other tasks were things I’d prepared for in former roles. In the future, I hope that the technological and design skills I learned at The Nation will help me succeed as a future editor of a press. In this future role, I will need to know how to format poems and really conceive of poetry as printed matter. This internship experience honed my already present skillset and closed the gap regarding skills I will need moving forward. Beyond this growth in my skillset, I was able to interact with the work of people in the literary industry I would never have met prior. These were writers I’d read, but only in nal dra s. It was good to read their work in its early stages of submission and to be able to o er feedback and suggestions that would help improve a poem. I was especially grateful

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 34

to work with the translations of Ilya Kaminsky and Katie Farris, whose practices I’ve admired for many years.

I worked with a substantial team at the magazine itself as well. From Managing Editors to other interns, my work was always collaborative. I learned to assert myself among a team of people, as I tend to be someone who listens more than I speak. I felt encouraged at The Nation to have an opinion. My thoughts and ideas were always valued. I would absolutely recommend the Boilers Work Internship program to my peers. The opportunity to o er voluntary services to an organization while developing themselves professionally is a fantastic one.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Anthony Okafor is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing (Poetry) with an expected graduation date of 2024. Anthony is “interested in poetry that leaps beyond the parameters of the page toward action.”

KAI-JEN CHENG

The Boilers Work Internship Program supported me in exploring my career aspirations this past summer. I was the marketing and promotions intern for the Lafayette Aviators. This internship taught me a lot, not just about the marketing/promotions aspect of the sports/baseball industry, but also about the management side of a sports organization, and the skills needed in all professional work. I feel it prepared me well for entering the workforce a er graduation. I acquired and sharpened many so skills in these three months. My most signi cant accomplishment of this internship was taking over as the head of promotions for the last 8 games of the season due to my supervisor resigning for another job elsewhere. I led the entire promotions sta (camera crew, announcer, videoboard operator, on- eld host, event sta , mascot, and guest services) in executing 8 of our 30 home games. It helped me improve my management, leadership, teamwork, and communication skills. Furthermore, one of the most valuable parts of this internship was something that couldn’t be taught. It isn’t a technical skill, nor something one can prepare for – and that is cultural exposure. In the rst three weeks of this internship, I felt like I experienced more of the American culture than I had in the previous ten months in Krannert. The workplace culture, the sports culture, and the community culture are all parts of what I wanted to experience when I rst applied to graduate school in America. Understanding sports and fan culture is such an essential part of marketing in the sports industry. For someone who didn’t grow up with this cultural background/environment, no matter how good their skills are, they wouldn’t be able to succeed in this business without knowledge of the culture. I would de nitely recommend the Boilers Work Internship Program to other students that are determined to pursue their dreams. They provide a great opportunity and tremendous support for you to explore your career.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kai-Jen Cheng completed his Master of Science in Marketing and Marketing Analytics. He aspires to become a marketing director or manager of a major sports organization.

ROSE DUNBAR

My name is Rose Dunbar, and I am a second-year Master of Public Health student at Purdue. Upon graduation in May, I would love to pursue a career focused on maternal and child health, breastfeeding education, or adolescent nutrition education. Over the summer I was able to explore my career interests through my internship at the Indiana Department of Health in the Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity. Throughout my time there I gained knowledge and experience on topics of local food procurement, SNAP assistance, breastfeeding support, the grant reviewal process, and early care and education resource development.

InnovatED | Issue 4 | Page 35