PROTEI N pro d ucers

FALL 2025

FALL 2025

2025 Volume 13 Issue 3

Thank you to all sponsors for supporting PAC & Protein Producers

Animal Health International

Bimeda

Daniels Manufacturing Co.

Huvepharma

Idexx

Kemin Animal Nutrition & Health – North America

Lallemand Animal Nutrition

Novonesis

Vaxxinova, US/Newport Laboratories

Zinpro

FRONT COVER PHOTO CREDIT

Thank you to Dr. Doug and Jan Ford for the photo from their ranch on the South Platte River in Snyder, Colorado.

EDITORIAL TEAM & PRODUCTION TEAM

Brandi Bain

Keli Huddleston

Heather Newell

Lisa Taylor

Jose Valles

It is time to welcome back our loyal readers and extend a warm greeting to those who are joining us for the first time. I am grateful to bring you this welcome to the fall issue of Protein Producers.

As the crisp autumn air settles in and the leaves turn from vibrant greens to warm shades of orange and gold, we find ourselves in such a pivotal season. Fall is not just another chapter in our year; it is a season rich with activity and reflection for everyone in the industry. Personally, I like to pause and reflect on my “why.” When you understand your “why,” the work becomes more than another task; it becomes a source of fulfillment and joy for what you do, no matter how big or small the job is. That “why” fuels your strength and perseverance as fall activities ramp up. With harvest in full swing, we are gathering the fruits of our labor, yet we cannot forget about our cattle. The towering crops have given way to stubble, and before long, those same fields will be full of grazing cows while calves make their way to the feedyards. This transition just tells the story of a year marked by dedication, hard work, and unforeseen challenges. For most in our industry, fall is a time of preparation. Temperatures begin to dip, and the focus shifts to readying our livestock for the harsh winter months. Now is the perfect opportunity to evaluate our herds, make the hard decisions, and prepare for the colder weather ahead. Are your shelters winter-ready and windbreaks in place? Is your feed and forage supply adequate to get through a bad winter? These are the questions that will keep you ready as we transition into the brisk months of winter. But in the midst of it all, let us remember to celebrate and be thankful for the land’s bounty and the tireless hands that made it happen.

This fall issue of Protein Producers is filled with practical and relevant information. In the cowcalf section, we cover Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD), fly control, water quality, and blackleg prevention. For feedyard producers, we take a closer look at hairy heel wart and hospital facility design.

As you settle into this issue, we hope you find something you can take back to your operation in these pages. I hope you have a wonderful fall season and a cooperative journey into winter. Thank you for the work you do. It is hard work, with some days harder than others, but you continue to show up each and every day. We are proud to be part of your fall season. Happy reading!

"To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven." - Ecclesiastes 3:1

Taw Fredrickson, DVM

Production Animal Consultation

Sioux City, Iowa

We want to thank the industry partners, publications and associations who have provided content to Protein Producers. Also, a big thank you to our readers for supporting us, offering content and helping us improve each issue. We could not do any of this without all of you!

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and information expressed in this magazine are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect Production Animal Consultation’s policy or position.

Tulathromycin options outnumber the stars,

Looking for out of this world support, in addition to an all-star product line?

On top of the benefits of tulathromycin, VACASAN® (tulathromycin injection) is paired with Huvepharma’s expert support. We work hard to bring you quality products backed by capable professionals who are ready to assist with technical or sales questions.

When discussing tulathromycin options with your herd’s veterinarian, choose VACASAN® .

By Drew Magstadt, DVM, MS, Iowa State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

When talking about diseases affecting cattle and what we can do to support cattle health, it can often seem a bit like looking into a bowl of alphabet soup. You have a few common players that most people know about: BVDV, IBR, BRSV, PI-3 and vaccines for these agents (many of which are MLVs). Dairy cattle recently made IAV part of the cattle conversation. The cow that stole Christmas a couple decades ago did so through a diagnosis of BSE, and there are several acronyms we all hope we never get to experience up close (namely, FMD). Epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus (EHDV) and Bluetongue virus (BTV) are two separate but very similar viruses that can each cause issues in cattle from time to time.

As previously stated, these viruses are incredibly similar: they both belong to the same genus ( Orbivirus ) and often result in fairly similar signs/lesions in the primary species they affect. EHDV most often affects white-tailed deer which are highly susceptible to infection; the most common species affected by BTV is sheep. However, reports of confirmed disease due to these viruses extend to various species of deer and multiple different domesticated ruminants (goats, llamas, yaks, bison). Multiple strains of both viruses exist (called serotypes) and both are spread via the Culicoides sp. of biting midges (aka, no-see-ums). Other insects have been shown to have little to no role in virus transmission, so spread is essentially limited by the geographic areas where biting midges are present and the time of year where these insects are alive/active.

Deer affected by EHDV are often found dead; those that are not may be found breathing heavily with a high fever, weakness, and lameness. The most striking changes often occur in the mouth and head/neck; the lining of the mouth often sloughs and tissues of the mouth/head/neck are often severely swollen. Bloody saliva may be found coming from the mouth, and some animals may lose their hooves. BTV in sheep can look similar but is generally not quite as severe. Affected sheep have a swollen face/muzzle, nasal discharge, and oral ulcers. The tongue may be blue/swollen and sticking out of the mouth.

Death loss in white-tailed deer can be very high, particularly in captive/farmed deer operations with high population density. The impact of BTV infections in sheep is variable and often depends on the strain as well as the level of existing immunity. When we examine animals that have died due to these viruses, we typically see scattered hemorrhages throughout the carcass affecting many organs in addition to the previously discussed changes to the face/neck/ mouth. Swelling due to edema and fluid within the lungs are also common; these changes all stem from damage to blood vessels caused by the viral infection.

These viruses can become impactful in cattle when they are introduced into areas where the cattle herds have not previously been exposed. Most infections of EHDV and BTV in cattle are thought to be either subclinical (not cause symptoms) or cause very mild/minor impacts on the herd. Changes are similar to but generally much, much milder than infections in whitetailed deer or sheep: swollen faces, ulcers in the mouth, excess salivation, and lameness are most common.

Death loss in cattle during outbreaks has reportedly been very low. With that being said, reports during a recent EHDV outbreak in southern Iowa often described a significant number of cattle being found dead on pasture with severely swollen faces and sloughed tissue in the mouth. Another potential impact in cattle is on fetal development in infected pregnant cows. Both viruses can interrupt fetal development and result in abnormalities such as domed heads and small eyes; other more common viruses (like BVDV) can cause similar defects in fetuses.

Both of these viruses are fairly easy to detect in animals showing signs of disease; PCR tests have been developed for each of these agents that can be run using either whole blood from live cattle or spleen tissue collected at necropsy. Brain tissue can also be used to detect each virus in cases of fetal defects. Tests for antibody to EHDV and BTV are also available to assess whether an animal has previously been exposed to either virus. However, these viruses are similar enough to each other that antibody testing results can be difficult to interpret; a positive test for BTV antibody may actually be the result of previous EHDV infection, depending on the test.

Detection of these viruses and/or suspicion of disease due to them is reportable in many states. Despite the widespread geographic distribution of the viruses and the biting midges that spread them, some countries require diagnostic testing

for embryo export purposes to show that donors are negative at the time of collection; detection of either of these viruses in blood samples can potentially be disqualifying. Consult your herd veterinarian if you have questions regarding embryo export, and talk through the export requirements and the logistics of meeting those requirements for each intended destination country.

Vaccination for these agents as a control measure is complicated: vaccines may be available or able to be produced in commonly affected areas of the world, but how well they work is highly dependent on the strain

animals to biting midges, but many of these recommendations just are not terribly feasible in large herds occupying large pastures. Insect repellents may be effective in small areas. Avoiding areas with heavy insect populations (low lying, damp ground) and times of high insect activity/feeding (dawn/dusk) may be helpful but difficult to execute.

Drew Magstadt is a Clinical Associate Professor and has been a veterinary diagnostician for the past decade at the Iowa State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. He grew up on a ranch in central North Dakota and spent two years in mixed animal practice. His research interests generally stem from real-world case submissions and include applied research into infectious diseases of food animal species.

By Russ Daly DVM, MS, DACVPM (Epidemiology), South Dakota State University

Finding a dead calf on pasture is never pleasant. The lost value of the calf and the logistics of retrieval and disposal are bad enough. But there is also the lingering question of what caused the death – and how many others might meet the same fate.

That question is sometimes hard to answer in grazing settings. Expansive pastures make it a challenge to check every animal every day. Warm summer temperatures and predators affecting the carcass can cloud a veterinarian’s ability to identify the tell-tale lesions that solve the mystery. In addition, there are a lot of potential causes of sudden death in calves on pasture, including lightning strikes, lead poisoning, respiratory disease, ruptured stomach ulcers, and blackleg.

Many producers are quick to write off blackleg as one of these possibilities. Blackleg is one of the oldest and most recognized causes of death in grazing calves, yet few producers have encountered cases – for reasons we will get to soon.

Blackleg progresses so rapidly once clinical signs appear that those signs are only very rarely noticed; dead calves are by far the most common presentation of this disease. The culprit of this illness is a bacteria called Clostridium chauvoei . An important feature of these germs is their ability to form spores, which are built to survive environmental extremes like heat and dryness. These spores are found in many cattle environments, but it is on pasture that calves are most often exposed.

Calves eat the blackleg spores while they are grazing. Those spores travel through the calf’s gut and are carried by white blood cells to muscle, where they lie dormant and might never cause any problem. In certain calves though, when something happens to change the oxygenation of that muscle – a bruise, strenuous exertion, or stress, for example – the bacteria activate, multiply, and produce toxins. Those toxins kill off the muscle tissue – which is bad enough – but they also travel throughout the body, shutting down the calf’s vital organ functions and causing a rapid death.

The muscle damage is about all the veterinarian has to go on when making a postmortem diagnosis in an affected calf. Oftentimes the rear leg muscles will harbor an area of necrosis (tissue death) that appears dark brown, filled with gas pockets, and exudes a smelly redblack fluid. Such a finding seals the diagnosis; the veterinary diagnostic lab can confirm it by growing Clostridium chauvoei from those tissues on a culture plate.

Sometimes, though, the damage caused by the blackleg bacteria can be much more subtle in the affected carcass. The SDSU Animal Disease Research and Diagnostic Lab has documented more than a few blackleg cases where tissue

damage is mild and hard to see. This damage can affect the heart, the diaphragm, and the tongue (all of them muscle tissue, by the way). Even subtle areas of damage can support enough growth of the bacteria and liberation of its toxin to kill the calf. Decomposition out on pasture makes detecting these subtle lesions even harder.

A disturbing aspect of blackleg is that it often preferentially affects faster-growing, better-muscled calves; perhaps their muscles are more prone to the oxygen tension that sets off the chain of disease events. For reasons mostly unknown, it is calves – not cows or bulls – affected by this disease.

Fortunately, blackleg is a very preventable problem. Vaccines against the disease are numerous and effective. Most people know these as “7-way” or “8-way” vaccines that include protection against other members of the Clostridium family, such as overeating disease and tetanus.

Vaccinating calves prior to pasture turnout is a proven preventive method against blackleg; outbreaks are rare in vaccinated herds. Vaccine labels carry instructions for giving a booster dose 3-6 weeks after the first administration; in certain problem pastures, this booster requirement could prove important. The widespread use of these vaccines has made blackleg fairly uncommon nowadays.

Producers who do not regularly vaccinate calves for blackleg at the onset of the grazing season are essentially “rolling the dice,” as most pastures house the bacterial spores. If you are in this category, it is a good idea to discuss a vaccination program with your veterinarian. And scouting those pastures for the unfortunate –but hopefully rare – instances of calf death loss will help the chances you and your veterinarian can determine the cause.

Russ Daly, DVM, MS, DACVPM (Epidemiology), is the Extension Veterinarian and a Professor in the Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Department at South Dakota State University in Brookings, South Dakota. Dr. Daly practiced for 15 years and was a partner in a mixed-animal veterinary practice in Montrose, South Dakota, before joining the faculty at SDSU. The connections formed by Dr. Daly’s varied set of responsibilities – disseminating animal health information (gained through communications with practitioners, extension professionals, and laboratory diagnosticians), organizing veterinary continuing education, and teaching undergraduate, professional, and graduate students – allow him to uniquely serve professionals and citizens as a resource on animal and public health issues in South Dakota.

By Steve Ensley, DVM, PhD, Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

Drinking water quality is critical for the health and productivity of beef cattle. Poor-quality drinking water may cause reduced feed intake, poor weight gain, reproductive issues, and even toxicity. The following table has guidelines for animal drinking water.

The main concern with drinking water for cow-calf operations is adequate drinking water availability. The highest death loss in cow-calf herds associated with drinking water is water deprivation/sodium toxicosis. These issues are more common during the summer months with elevated environmental temperatures but frozen drinking water devices in the winter also cause health issues and death loss.

Hauling drinking water for cattle in tanks previously used for farm chemicals including nitrate/nitrite is also associated with high death loss.

By Steve Ensley, DVM, PhD, Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

One of the biggest issues with the drinking water quality of animals is the water report issued by the water testing laboratory. Water testing is done by many commercial laboratories with the results reported as human drinking water parameters. When the water laboratories issue their report, the report uses human drinking water standards to report results. Many results get flagged yellow or red because they are out of normal range. None of the ranges for this water testing are meaningful because human drinking water standards do not equate to animal drinking water standards. As a

Drinking water quality is critical for the health and productivity of beef cattle. Poor- quality drinking water may cause reduced feed intake, poor weight gain, reproductive issues, and even toxicity. The following table has guidelines for animal drinking water.

Key Water Quality Parameters for Beef Cattle

Parameter

Total Dissolved Solids (TDS)

Nitrate (NO₃-N)

Sulfates (SO₄)

< 3,000 mg/L (ppm)

< 100 mg/L (as nitrate), or < 10 mg/L (as nitrate-nitrogen)

< 500 mg/L

pH 6.0 – 8.5

Hardness (Ca + Mg) Not a concern

Iron (Fe)

Bacteria (E. coli, coliforms)

Colonies per 100 mL

Algae or Blue- Green Algae Absent

Safe for all cattle. 3,000 mg/L is usually acceptable but may reduce performance in sensitive animals.

Elevated concentrations can cause nitrate toxicosis, especially in late-term pregnant cows.

Total dietary sulfur concentrations above 1,000 mg/L can cause polioencephalomalacia (PEM).

Cattle can tolerate a broader range, but extremes may aVect intake.

Is flagged when using human drinking water standards

No good data on whether it aVects animals

Indicates fecal contamination. Risk of disease in human drinking water but not animals. There is always fecal contamination in surface water.

Cyanotoxins from algae blooms can be fatal. Monitor ponds, lakes, streams, dug outs, etc. Not a concern with water troughs.

result, there is much concern with the results that are reported when in reality, there is no concern. Many reputable testing laboratories use reference ranges that have no peer reviewed data. Much of the reference ranges came from extension papers or other references that are not peer reviewed.

Reference ranges for coliforms are a good example of references with no peer reviewed data. Coliforms are a significant concern in human drinking water. Coliforms are measured per 100 ml of water. If even one coliform per 100 ml is detected in the drinking water, a boil order is initiated, and shock chlorination is performed on the affected water. Bacterial, viral, and parasitic contamination of drinking water occurs in human drinking water. Bacterial, viral, and parasitic contamination of drinking water of animals could occur but is low on the level of concern for drinking water. If you do not find coliforms in surface water, something is wrong with your testing method.

We want to provide the very best drinking water we can for our animals, but their level of concern from the appearance of the water, the smell of the water, and the turbidity of the water is low. If anyone has watched animals drinking from a pond, dugout, or creek, they have seen cattle urinating and defecating in the same water that other cattle are drinking. After a rain, cattle in a dirt lot will drink water from the puddles in the lot and they have no negative effects.

Future work with drinking water quality for animals should include working with one analyte

at a time to find at what point animal health and performance is negatively impacted. Once we know that, then we can include increasing several analytes at a time to see when animal health and performance is negatively impacted.

There is some work going on now with costeffective methods of treating wastewater to make it suitable for animal drinking water. These treatments have to be cost effective and able to meet the high demands for drinking water. A 100,000-head feedlot would consume approximately 1,389 gallons per minute (GPM) on average, assuming 20 gallons per head per day.

When collecting a water sample, the water collection bottle needs to be as clean as possible but not disinfected if you do not want to measure the coliform count. If you are going to measure coliform in water, the sample needs to be collected as aseptically as possible. It is easiest to get a drinking water container from the local convenience store. To collect an animal drinking water sample from a well, you need to collect one as close to the well as possible, then a second sample at the most distant part of the water distribution system. To collect a sample from surface water, collect the water sample at least a few feet away from the bank and fill the bottle, dump it out, and then refill it. After collecting the water sample, keep it cool and get the sample to the laboratory as quickly as possible.

Dr. Steve Ensley graduated in 1981 from Kansas State University with a DVM. His father was a mixed animal practitioner in northeast Kansas. After 14 years in mixed practice in the Midwest with his father, he received a MS and PhD in veterinary toxicology at Iowa State University completing his PhD in 2000. Dr. Ensley has worked for the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (ran the North Platte diagnostic laboratory), Bayer AG in Kansas City, Iowa State University for 15 years, and presently Kansas State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. Dr. Ensley’s interests are clinical veterinary toxicology and applied veterinary toxicology research. Dr. Ensley has published extensively on applied veterinary toxicology and has given numerous presentations on these topics. Food animal veterinary toxicology is his passion.

Robert Feiock is a second-year veterinary student at South Dakota State University PPVM, with the goal of becoming a beef cattle consultant for clients in all sectors of the industry. Robert’s interest in production animal agriculture started early, where he was exposed to farming, feeding cattle, and the meat packing industry from a young age. This encouraged him to pursue an undergraduate degree in animal science as well as work experiences that provided hands-on exposure.

Robert decided to complete a summer internship with PAC because of PAC’s commitment to their core values and their mission of improving lives through veterinary medicine, which is one of the reasons Robert chose to attend veterinary school in the first place. Robert’s favorite part of his summer in southwest Kansas was working and learning alongside PAC veterinarians, feedyard managers and cowboys, and everyone he met throughout the internship.

Robert originally hails from outside Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and in his free time, he likes to spend quality time with his family and friends, feed cattle, and play a little golf.

By Cassandra Olds, PhD, Kansas State University

Fall may seem like a strange time to be thinking about fly control, but it is the perfect time to review what you did this summer and start planning for next year!

Developing an integrated fly control program is essential to reduce loss not only next year but for years to come.

Knowing which kind of fly you are dealing with is the first step in developing your program. There are three major flies which cause loss in pastured cattle: horn, stable and face flies. Horn flies are small flies seen on the back and bellies of cattle with the fly head facing downward (Figure1). Cattle under fly pressure will often toss their heads back trying to disturb the flies, tail swish, bunch together

and bump up against each other in an effort to give their flies to their herd mates. Stable flies are larger and prefer to feed on the legs with their head facing up towards the sky (Figure 2). Fly worry signs include leg stamping, belly kicking, tail swishing and animals bunching together showing general agitation. Cattle can sometimes be seen bunched up against a fence line or standing in ponds to try and escape painful bites. Face flies are often found around the eyes, nose and mouth and transmit the pathogens which cause pinkeye. Animals may show general agitation and head shaking (Figure 3). Fly control is not a ‘one size fits all’; these flies have different habits and breeding sites and you need to target your fly control approach to each species. Watching your animals for fly worry behaviors and observing areas flies are found should be used to determine which flies you have and build on your control approach.

The most impactful fly control intervention for population reduction will always be

removing breeding sites. Each female fly will lay several hundred eggs during her lifetime. Horn and face flies will only lay eggs in fresh intact manure. Maggots need to be within the manure pat to survive and will only leave the manure when ready to pupate and become adults. Dung beetles (Figure 4) are the unsung heroes of grasslands, removing and burying manure which not only removes the breeding site for flies but also for gastrointestinal nematodes. Dung beetles reduce pasture fouling, improve soil aeration and nutrient cycling and are very susceptible to macrocyclic lactones so avoid using injectable and pour-on avermectins (abamectin, eprinomectin, ivermectin, etc.) during spring, summer and early

fall. Due to their faster elimination times, white wormers (benzimidazoles) may be less damaging to dung beetles, but their negative impacts have not been established in the native dung beetle species we need.

A feedthrough insect growth regulator (IGR) blocks the ability of flies to develop within the manure pat. To be effective, each animal must consume the correct amount; however, cattle consumption of free choice mineral varies significantly. This causes some individuals to eat either too much or too little with too little being the major concern. Underdosing leads to accelerated development of resistance resulting in reduced efficacy over time. There is a common misconception that insects cannot become resistant to IGRs, which has been shown in multiple studies to be untrue. If you

do use a feedthrough IGR, rotate annually between a methoprene (e.g., Altosid) and diflubenzuron (e.g., Clarifly, Justifly) based product to slow the rate of insecticide resistance developing. While garlic has received a lot of attention in recent years, controlled trials have shown no difference in fly burdens between cattle which are given garlic and those who are not.

Figure 4. Look for large beetles in manure pats or rolling balls (L). Larval stage of dung beetles develop in buried manure balls removing breeding sites for horn and face flies (R).

In contrast to horn and face flies which breed in fresh manure, stable flies will happily breed in any wet and decaying plant matter, especially if contaminated with animal waste. Large round hay bales are a primary breeding site for stable flies so reduce hay waste by feeding high quality hay and spread waste to dry it out, thereby killing maggots and removing the breeding habitat.

Removing flies from animals reduces fly worry and economic loss as well as reducing the overall population. Horn flies stay on their chosen animal 24/7 and will die within a few hours of being off the host. This makes on-animal control options more effective than for stable or face flies which are only on the animal for a few minutes, spending the rest of their time sheltering in vegetation.

The Bruce’s walk-through trap can be very effective for horn fly control if animals pass through it regularly ( https://www.iowabeefcenter.org/bch/ HornFlyTraps.pdf ). These are also effective against other fly species including stable flies, face flies and tabanids (deer and horse flies). The more often cattle walk through, the more flies are removed so placing them on the way to water or feed is most impactful.

Adult animals can carry lower horn fly burdens (approximately 300 flies) without any negative impacts and any chemical control options should only be used once flies go above this level (Figure 5). Insecticides come in many formulations and application methods. With so many options, it is often easier to just stick with what has been used year after year. Unfortunately, this approach drives insecticide resistance, limiting your choices in the long run. Insecticides should be used sparingly and only as part of a larger integrated pest management program.

Ear tags offer a convenient method for horn and face fly control, as well as some ear associated ticks. Tags are available in all three major chemical groups (pyrethroid, organophosphate and macrocyclic lactone). You should rotate chemical class annually; Table 1 gives some options for each group. In field trials, tags offer approximately 100 days of horn fly reduction compared to untagged cattle. The mistake people often make is to put tags in too early as cattle go out onto pasture in the spring. The tag’s most effective time period is effectively being used up while fly numbers are relatively low. Although it may be less convenient, delaying tagging by a month or two will give you protection over the peak fly period. While adult animals can maintain lower fly burdens without loss, weaned calves are less tolerant to parasitism. Tagging stocker calves before going onto pasture will significantly improve average daily gain.

To get the most bang for your buck, follow good tagging practices. Insecticide ear tags work by coming into contact with the skin surface. Insecticide transfers from the tag to the skin and spreads through the natural coat oils. Tagging only one ear is a common practice but only half the body is protected if you use this approach. This is particularly important when using tags for face fly control. Tag cows and weaned calves but not calves still on the mother. Tagging bulls is also not recommended because they do not have the neck

Year 1: Organophosphate (IRAC Group 1B)

Corathon

Dominator

Max40

2:

(IRAC Group 3A)

Year 3: Macrocyclic lactone (IRAC Group 6)

CyLence Ultra XP820

GardStar Plus TRIZAP

PYthon II

Optimizer PYthon II Magnum

Patriot

Saber Extra

Table 1: Ear tag options for good annual rotation

mobility to make tagging effective. Do not daisy chain tags because it does not give enough contact to be effective. Remove tags when they lose efficacy or at the end of season and do not retag cattle within the same season. A pour-on can be used for horn fly control and should be used in the same rotation as ear tags. Bear in mind that macrocyclic lactone pour-on will impact your dung beetle populations. If you do not want to use macrocyclic lactone products, use organophosphate chemicals for two years followed by one year of pyrethroid chemicals in a 2-1-2-1 rotation.

If using multiple application methods together, make sure you synchronize chemical class. For example, if you use a self-applicator to treat animals in pasture with an occasional spray, make sure that both chemicals fall in the same group. For example, if you have Prozap in your back rubber, the active ingredient is permethrin which is a pyrethroid (IRAC group 3A). Make sure you pair it with a pyrethroid spray such as Permectrin II or Permethrin 10 rather than Co-Ral which is an organophosphate so that all chemicals for that year fall into the IRAC group 3A. If using an organophosphate like Prolate/Lintox-HD in a back rubber, you can also use it as a spray, Co-Ral or any another organophosphate (IRAC code 1B) based spray. The Vet Pest X website is a searchable database which can help you make insecticide product selections ( https://www.veterinaryentomology. org/vetpestx ).

Injectable macrocyclic lactones have become popular due to their convenience and longer coverage length. Due to the long elimination times, they will select strongly for insecticide resistance and should not be used for insect control.

Pasture management can be used to supplement your fly control practices. In areas where burning is permitted, pasture burning in the early spring can be used to reduce both fly and tick populations. Horn flies are capable fliers with estimated flight range of 3-10 miles. Pasture rotation can be effective especially the further away cattle are moved. Even if you cannot move cattle far distances, making the newly emerged adult flies move even a little further to reach cattle after emerging can reduce chances of the fly reaching a host.

In conclusion, watch cattle to identify which fly species you have and then build your program to target both larval and adult flies. Rotate chemical class to slow the spread of resistance and always use according to the dosage guidelines. Store unused chemicals in a cool dry place out of the elements to preserve their shelf life.

Note: All references to commercial products or trade names are made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement by K-State Research & Extension is implied.

Dr. Cassandra Olds serves as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Entomology at Kansas State University where she has a 50% Research, 30% Teaching and 20% Extension appointment. She received her PhD from the University of Basel in 2012 and underwent postdoctoral training at Washington State University and University of Idaho. She serves as the Veterinary Entomology Extension specialist for Kansas but also provides services to other states. Her research and Extension program are integrated to tackle producer’s insect and tick problems. She works closely with producers and veterinarians to evaluate the impact of arthropod pests directly in the field with the goal of developing sustainable pest control strategies to mitigate economic losses.

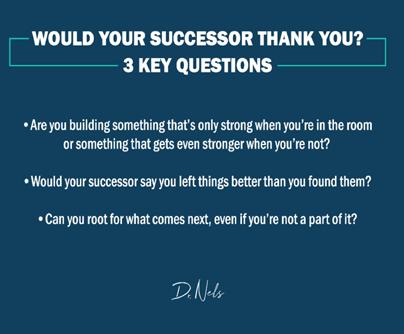

WOULD YOUR SUCCESSOR THANK YOU?

Life moves forward, no matter what. I learned this when our son was accidentally shot and paralyzed in 2020. My wife and I were removed from our work for 10 days right off the bat, and I missed a total of 17 days over the first several weeks. Unannounced, unplanned, and unforeseen. In the blink of an eye, I was removed from leading a veterinary practice and from consulting feedyards for a brief period. The good news is, without missing a beat, the clinic marched forward successfully and my feedyard clients were taken care of by other PAC veterinarians.

By Nels Lindberg, DVM, Production Animal Consultation

This kind of continuity in business requires intentional planning and deliberate action. At AMC, I had been slowly leading, growing, and pouring into my partner, Dr. Ty. We had built trust step by step, little by little, as I handed things off to him and coached him through successes and failures as needed. At PAC, we had worked to expand our team of veterinarians and team members over several years.

Whether you are a head cowboy, mill manager, feedyard manager, owner, or other team leader, I challenge you to continually think about the future of your team or company. Have you planned for the day you are gone or done so that your successor will thank you? This process may feel uncomfortable, or you may not be ready to begin the process because you just started in

your current leadership position. That is okay; I always coach leaders and teams not to rush the process. It takes patience, intentionality, vulnerability, humility, and often some painful bumps in the road over many years. Those involved with and affected by the transition often get nervous, wondering what is coming and what it means for them.

As you think about identifying and building up your successor, a great place to start is to look for those who get it, want it, and can do it (GWC) and also believe in and live out your vision, mission, and core values. Depending on your role in the organization, this may take 1 year, or it may take 5 to 10 years. Regardless of the position, the principles remain the same.

Answering the questions in the graphic below with humility, honesty, and the future success of the organization in mind is key. Ask yourself these questions routinely, using them to stimulate positive change and growth in your organization.

These questions are incredibly simple; yet many businesses, teams, or organizations may not be able to answer them all favorably. Every leader must act intentionally to create an environment where his or her successor will answer these questions with positive gusto and bring even more success to the organization.

As I have gotten older, I have come to understand that some businesses do not need to survive forever. However, we are in the noble business of producing beef, and I believe it is our obligation to identify, build, and grow our successors so that our contribution to beef production continues long after we are done and gone.

Dr. Nels Lindberg is a people coach, team coach, business coach, and keynote speaker, available virtually or in person. If you have any interest in these opportunities, please reach out to his office at 620-7921265 and visit with his righthand lady, Jill.

Vaxxinova takes the guesswork out of finding solutions for your complex herd health issues. Our advanced diagnostics allow us to see the exact issues hiding in your herd so we can create a customized vaccine or recommend the appropriate combination of commercial vaccines.

Talk to your Vaxxinova Representative or visit www.vaxxinova.us.com to learn more.

By Erik Loe, PhD, Midwest PMS

In 1963, Dr. Lofgreen wrote an article for the Western Livestock Journal titled: “Net energy – the new way to reckon rations.” He wrote that to further the daily use of the California Net Energy System and to gain common use of the net energy terms as standard feedlot lexicon. A proper reference to Dr. Lofgreen in any manner possible ensures that his legacy endures and to note the importance of his and Dr. Garrett’s timeless work. Now, let’s discuss digital dermatitis/hairy heel wart/hairy wart/papillomatous digital dermatitis/bovine digital dermatitis/strawberry.

Feedyards, cattle owners, and professional advisors have dealt with the management and economics of an increase in feedlot cattle lameness. We have made great strides in identifying, treating, and now proactive management of digital dermatitis (DD). Digital dermatitis robs cattle of retained energy, decreases daily gain, and lowers overall performance. An example of loss in performance from Kulow et al. (2017) was a 0.31 lb/d lower ADG and 12 lb lighter hot carcass weight. Regression data from Döpfer et al. (2018) showed that feedlot heifers with M4 lesions lost 0.34 lb/d of carcass weight compared with cattle without DD. The decrease in body weight gain and the management of lame cattle, whether it is treating individuals or housing them in designated pens, is costly and adds another level of daily management at feedyards.

As has been described by many, DD was first reported in 1974 in Italy (Cheli and Mortellaro, 1974). The classification of the types of DD lesions was described by Döpfer et al. (1997). Those authors classified the lesions as M-stages with the M standing for Mortellaro.

It is important to understand these M-stages. To further review the DD terms, here are the M-stages defined by Döpfer:

M0- Normal digital skin without signs of DD.

M1- Early, small circumscribed red to gray epithelial defect of less than 2 cm in diameter that precedes the acute stages of DD (M2). In addition, M1 stages can appear between acute episodes of DD lesions or within the margins of a chronic M4 lesion as an intermediate stage.

M2- Acute, active ulcerative (bright red) or granulomatous (red-gray) digital skin alteration, >2 cm in diameter, commonly found along the coronary band in addition to around the dew claws, in wall cracks, and occasionally as a sole defect.

M3 -Healing stage within 1 to 2 days after topical therapy, where the acute DD lesion has covered itself with a firm scab-like material.

M4 -Late chronic lesions that may be dyskeratotic (mostly thickened epithelium) or proliferative or both. The proliferations

may be filamentous, scab-like or mass proliferations.

M4.1- The additional stage refers to the chronically affected foot that displays the M4 stage in addition to the M1 stage.

The primary points to be made from the above classification is that cattle develop small, gray, scaly or flaky lesions that develop into M2 lesions. The M2 lesions typically cause cattle to express signs of lameness. Cattle with DD may stand with a raised hoof and not wanting to stretch the hoof out, keeping it bent distally with the point of the claw pointing down to prevent any skin movement on the heel where there is an active lesion. They may shake their affected hoof. An observant feedyard owner that is well schooled on DD termed the phrase “heel wart dance”, where cattle shift weight from hoof to hoof to relieve pressure and discomfort. Other characteristics of lame cattle with DD are cattle that lay flat on their side to get weight off of their hooves or cattle that lay at the back of a pen or on a bed-pack for longer than normal intervals. These cattle have been observed to have more tag covering the majority of one side of their body. Cattle with DD commonly have less rumen fill and go to the bunk less frequently, potentially over consuming ration resulting in digestive disturbances. A colleague observed a higher risk of bloat in cattle with DD due to erratic bunk attendance. Those are subtle observations. They are important and commonly used to determine if a pen of cattle should walk through a foot bath.

The goal is to make sure that if there are any observed DD lesions, that pen is moved through a foot bath to prevent the development of advanced lesions (M2 or M4). Dairy research (Robcis et al., 2023) reported that it was more efficient time management to use foot baths versus pulling and treating dairy cattle for DD. Experience at feedyards confirms that to be true. In addition, feedyards may not have chutes equipped for handling hooves safely, further emphasizing that foot baths are safe, effective, and efficient in the intervention for DD. Most feedyards are executing this well. The feedyards that have a prevalence of M2 and M4 lesions need to improve their processes.

Foot bath requirements include: 1) long enough for all hooves to be submerged twice; 2) deep enough to cover the dew claws; 3) in a location where cattle move in a normal gait and safely; 4) re-charge the foot bath after each pen; and 5) drain and replace the foot bath solution when it is dirty, which may be after 100 head in small foot baths or after 1000 or more head in large foot baths. It is critical to ensure that there is active ingredient in the solution.

Researchers from University of Wisconsin, Iowa State University, USDA Bacterial Diseases of Livestock Research Unit in Ames, and University of Calgary have provided us with insight into the etiology and polybacterial characteristics of DD. A significant education has been provided by feedyards in western Iowa that have learned to manage the disease resulting in a decrease in M2 and M4 lesions. A recent paper by Caddey and De Buck (2021) described the microbial community of these lesions. Their meta-analysis showed that Treponema, Mycoplasma, Porphyromonas, and Fusobacterium have roles in DD. Of those species, the Treponemes have the largest relative abundance in DD lesions. Treponemes cause multiple bacterial infections in different species including humans and including relapsing skin infections (Antal et al., 2002).

Figure 1. An example of what Wilson-Weber et al. (2015) termed "a less typical lesion of DD" above the interdigital space.

during the feeding period. Expression of the disease is more commonly observed at heavier weights. An example of this occurred in an experiment conducted in Iowa (Döpfer et al., 2018) where the incidence was less than 3-5% through 187 days on feed and from that point on, as cattle were fed between 320 and 380 days, incidence moved between 22 and 27%. My thoughts on why we observe heavier cattle to more commonly have the disease is that it is a factor of the pressure on the hoof and lesion causing pain when cattle are heavier.

In a review by Palmer and O’Connell (2015), the authors describe hoof conformation playing a role in risk level of cattle developing DD. The height of the heel and the interdigital space have been shown to be a risk for developing DD such that lower heel height and narrower interdigital gap have increased risk. Observations of mine and others of cattle with heel wart agree with the report of Palmer and O’Connell (2015) where claws wear abnormally resulting in higher heel height because cattle walk on the front of the claws wearing them down resulting in abnormal growth and less wear on the heel. I classify cattle with abnormal hoof growth and DD to be cattle that were missed for treatment or intervention.

In the past, the common thought was that DD manifested after 120 days on feed. We have now learned that lesions occur at any time

There is a picture of a lesion on page 156 in the Wilson-Welder et al. (2015) review that was described as “a less typical lesion of DD (red circle).” That type of lesion is common in the interdigital space on the front of the hoof (Figure 1) These lesions are easily observed on the front hooves but commonly are not associated with lameness from my observations. However, when front hooves are infected with DD, weight loss is common due to lower bunk attendance and feed intake.

The length of time for DD to advance from an M1 lesion to an M2 takes time. Refer to the M-scores from Döpfer and colleagues (1997). The progression of M1 to M2 is likely days. The window for prevention is short. During the summer of 2024, in conjunction between Iowa Beef Council, Dordt University, myself, and colleagues (Mr. Evan Vermeer, Dr. Wes Gentry, and Dr. Dan Thomson), an observational

experiment was conducted. The objective was to identify 20 steers with active DD and treat them with 1 of 5 treatments. The treatments were applied directly to the lesion while the steer was restrained in a chute and the affected hoof positioned for observation and treatment of the lesion. The treatments were the exact solution as used in foot baths and the positive control was lincomycin. The treatments were:

1. Lincomycin

2. Iowa formula (salt, copper sulfate, and soap)

3. Formalin

4. Benzoic acid (Dragonhyde)

5. Sodium bisulfite (BeefUp)

As mentioned, this was observational. The steers were weighed on the day of the initial treatment and housed in a pen in a bedding barn. Subsequent treatments and weights occurred in 14, 15, and 20 day increments. Each treatment showed efficacy based on observations of lameness and body weight gain. Lincomycin, formalin, and sodium bisulfite had the most improved lesions. The benzoic acid product (Dragonhyde) coated the hoof very well though it also coated adjacent surfaces as well.

Keep in mind that this experiment had minimal replication. The objective was to understand acutely how typical foot bath solutions affected DD lesions. Figures 2 and 3 show the change in an M2 lesion over a 14-day period after being treated with the Iowa formula. Figures 4 and 5 show the change over the same period in an M2 lesion after being treated with formalin. Figures 6 and 7 show the change in a DD lesion after being treated with benzoic acid (Dragonhyde). Figures 8 and 9 show the change in a DD lesion after being treated with sodium bisulfite (BeefUp). The conclusion was that doing anything to disrupt the lesion’s biofilm was beneficial. These cattle

(primarily M2 lesions) gained 3.27 lb/d from 1385 to 1545 lb during this period. We did not have a comparison of gain for cattle during that period that did not have DD.

More university and industry evaluations of foot bath solutions need to occur. Many products are used. There are products like formalin that are effective but have safety concerns and a need for PPE to be used. Concentrations of products vary. Based on conversations with feedyards and industry professionals, there are preferred concentrations. There are a lot of comments that may or may not be based on any good information, let alone any hard data. Copper sulfate and zinc sulfate have efficacy, but there are issues with what to do with the spent foot bath solution.

There are excellent veterinarians working to help identify DD treatments. Professional hoof trimmers and feedyards are trimming hooves of lame feedlot cattle when necessary. From those interventions, advancements in getting cattle comfortable, allowing more weight to be gained, are occurring. Dr. Dan Thomson brought sodium bisulfite to our attention, which led Dr. Engelken at Iowa State University to conduct an experiment with it as a pen surface treatment. Its efficacy is being evaluated at other yards now.

Our experience is that multiple products have efficacy in getting cattle to exhibit less lameness which confirms previous data from Teixeira et al. (2010), presumably indicating less pain. This improves DMI post treatment which increases body weight. The improved locomotion and comfort of cattle is noticeable within hours to days following foot bathing.

Diets formulated by professionals considering industry norms (Samuelson et al., 2015) and at or exceeding requirements (NRC, 1996) are fundamental. Feedyards, cattle feeders, and professionals that have experience with a wide range of feedstuffs and diets understand that there are multiple variables contributing to the disease and that there are important nutritional characteristics to understand. There are people in the feed business that claim specific feedstuffs cause the disease or that a specific as fed percent inclusion will lead to DD. Those that have been involved over a duration of years and a range of diets understand that DD is not caused by an ingredient. Dogma based on limited observations or perpetuated by large personalities is folly. A feedyard in western Iowa in the Loess Hills had finishing cattle and dairy replacement heifers fed the same ingredients in diets formulated for the different production goals. The finishing cattle had DD, whereas the dairy heifers did not express DD. There are other diet-related observations that do point to a combination of ingredients and/or cattle movement or transport that may influence an environment where DD is more prevalent. These are important observations but are not to be considered causative but part of a complex microbiome at each feedyard. There may be specific nutrients that become more

concentrated in tissue that are used by specific bacteria to grow. These are unproven theories at this point.

Work that Zinpro has sponsored (Kulow et al., 2017 and Döpfer et al., 2018) shows an improvement in carcass weight and less M2 and M4 lesions. The feedlot industry adopted the use of more bioavailable trace minerals long before DD was a widespread issue. Diamond V NutriTek (NaturSafe for beef cattle) has shown efficacy (Anklam et al., 2025). Biotin has been shown to decrease DD in dairy cattle over a 12-month period (Hochstetter et al., 1998). The conundrum that we have is that all products add up to significant cost. Nutritional intervention is a cost to all cattle. The benefit to heel wart control may only affect 25% of the cattle with DD. At times, the cost of the intervention to the pen or feedyard as a whole is more than the benefit.

It is implicit that if a feedyard trims hooves, the individual doing the trimming is well trained by a professional hoof trimmer. For example, pictures sent to knowledgeable veterinarians or hoof trimmers can be used to give guidance to improve technique and outcomes. There is great knowledge and experience in that arena. Be mindful of clean instruments. Wells and colleagues (1999) pointed out that unclean trimming tools can spread the disease.

This depends on the severity and number of affected cattle. The typical protocol is to move cattle through a foot bath multiple days per week if the feedyard is behind treating for DD and have greater than 2% lame cattle in the pen. The 2% threshold is arbitrary. If there are cattle with DD in the pen, a foot bath should be considered.

Consecutive versus every other day? My preference is consecutive days. That is an aggressive approach to head off the problem. Many feedyards and advisers use that approach. Out of precaution, the concentration of the active ingredient in the foot bath needs to be correct. There are logistical and weather-related variables that dictate which is best at every feedyard.

We need to take a step back and assess production systems and consider previous management and environment. Transport, handling, and facility hygiene need to be monitored so that we can correctly understand where DD originates. There are bedding barns that are prone to have cattle with DD. Conversely, there are bedding barns that do not have cattle that express signs of DD. There is unproven dogma related to feedstuffs. There are feedyards with basic vitamin and mineral nutrition that have no issues with DD.

The experience that we have gained is that feedyards that have had DD will not necessarily continue to have cattle that are infected with it. It occurs in all pen designs. It appears in most breeds. It appears in most feeder cattle weight classes.

Appreciation is due to cattle feeders in western Iowa, most specifically Sioux County, who have helped teach the industry what DD is and how to manage it. There are active companies and industry professionals searching for products and management strategies to lessen the effect of DD and ultimately to lead us into a prevention of the disease. For now, diligent identification of DD and proactive management practices are proven to lessen the advancement of lesions. New tools

References

such as real-time DD detection apps such as developed by Dwivedi et al. (2025) should enable us to have the insight and eye for identification such as Dr. Dörte Döpfer and other highly trained personnel.

Critical contact points include:

• If a feedyard or pen has a history of DD, foot bath early

• Pen and trailer hygiene

• Cattle handling

• Proper nutrition

• Anklam, K., M. Aviles, J. Buettner, S. Henschel, R. Sanchez, S. Ordaz, I. Yoon, J. Wheeler, G. Dawson, and D. Doepfer. 2025. Evaluation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product on the prevention of digital dermatitis using an experimental infection model in cattle. App. Anim. Sci. 41:47-64. doi.org/10.15232/aas.2024-02567

• Antal, G.M., S.A. Lukehart, A. Z. Meheus. 2002. Review: The endemic treponematoses. Microbes and Infection. 4:83-94

• Caddey, B. and J. De Buck. 2021. Meta-analysis of bovine digital dermatitis microbiota reveals distinct microbial community structures associated with lesions. Front. in Cell. and Inf. Micr. 11:1-12. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.685861

• Cheli, R. and C. Mortellaro. 1974. La dermatite digitale del dovino. In: 8th International Meeting on Diseases of Cattle, Milan, Italy. p. 208–213.

• Döpfer, D., A. Koopmans, F. A. Meijer, I. Szakall, Y. H. Schukken,W. Klee, R. B. Bosma, J. L. Cornelisse, A. vanAsten, and A. terHuurne. 1997. Histological and bacteriological evaluation of digital dermatitis in cattle, with special reference to spirochaetes and campylobacter faecalis. Vet. Rec. 140(24):620–623 (Article). doi:10.1136/vr.140.24.620

• Döpfer. D. E.R. Loe, C.K. Larson, and M.E. Branine. 2018. Effects of feeding a novel amino acid-complexed trace mineral supplement on productivity and digital dermatitis mitigation in growing-finishing heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 96:suppl 2, Page 231, doi.org/10.1093/jas/ sky073.428

• Dwivedi, A. M. Henige, K. Anklam, and D. Döpfer. 2025. Real-time digital dermatitis detection in dairy cows on Android and iOS apps using computer vision techniques. Transl. Anim. Sci. 9:1-13. doi.org/10.1093/tas/txae168

• Hochstetter, T. 1998. Horn quality of the bovine hoof under the influence of biotin supplementation. DVM Inaugural Dissertation. Journal #2176. Free University of Berlin, Germany.

• Kulow, M., P. Merkatoris, K.S. Anklam, J. Reiman, C. Larson, M. Branine, and D. Döpfer. 2017. Evaluation of the prevalence of digital dermatitis and the effects of performance in beef feedlot cattle under organic trace mineral supplementation. J. Anim. Sci. 95. doi:10.2527/jas2017.1512

• NRC. 1996. Nutrient requirements of beef cattle. 7th rev. ed. Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, DC.

• Palmer, M.A., and N.E. O’Connell. 2015. Digital dermatitis in dairy cows: a review of risk factors and potential sources of between-animal variation in susceptibility. Animals. 5:512-535. doi:10.3390/ani5030369

• Robcis, R. A. Ferchiou, M. Berrada, and D. Raboisson. 2023. Management of digital dermatitis in dairy herds: optimization and time allocation. Animals. 13:1-20. doi.org/10.3390/ani13121988

• Samuelson, K.L., M.E. Hubbert, M.L. Galyean, and C.A. Loest. 2016. Nutritional recommendations of feedlot consulting nutritionists: The 2015 New Mexico and Texas Tech University survey. J. Anim. Sci. 94:2648-2663.

• Teixeira, A.G.V., V.S. Machado, L.S. Caixeta, R.V. Pereira, and R.C. Bicalho. 2010. Efficacy of formalin, Copper sulfate, and a commercial footbath product in the control of digital dermatitis. J. Dairy. Sci. 93:3628-3634.

• Wells, S.J. and B.A Wagner. 1999. Papillomatous digital dermatitis risk factors in US dairy herds. Preventive Vet. Med. 38:11-24. doi. org/10.1016/S0167-5877(98)00132-9

• Wilson-Welder, J.H., D.P. Alt, and J.E. Nally. 2015. The etiology of digital dermatitis in ruminants: recent perspectives. Vet. Med.: Res. & Rep. 6:155-164. dx.doi.org/10.2147/VNRR.562072

Erik Loe, PhD, has been a professional feedlot nutritionist since 2008. Prior to that, he was the SDSU Extension Feedlot Specialist and received graduate degrees from NDSU and K-State. He truly enjoys being at feedyards and working for them. He finds his colleagues professionally inspiring and challenging, a combination he values in line with one of his favorite quotes, from a previous National Security Advisor: “One always learns more from friendly critics than from uncritical friends.” Dr. Loe has many blessings, including being married to a wonderful lady and having two outstanding daughters.

Stress prevents your cattle from performing at their best. SecureCattle®, which has been sold globally for almost 10 years, is now available in the US. It is a maternal bovine appeasing substance (mBAS) which has been proven to alleviate stress — and the energy expenditure associated with stress — so your cattle can have better immune function, improved overall health and well-being, and optimized performance. Delivered through one convenient 5 mL dose applied to a single location on the top of the neck.

Pour on. Stress gone.

By Kip Lukasiewicz, DVM, Production Animal Consultation

When it comes to cattle health, hospital systems are one of the most important parts of any operation. The way we design and manage hospital facilities can make the difference between whether cattle recover and return to the home pen or whether they do not. Good design is not just about convenience. It is about animal well-being and comfort, operational efficiency and crew safety. It is also how we move the needle on the metrics that matter. Pen space provided, cattle comfort measurements, case fatality rate and treatment-to-death interval are the primary benchmarks. Medicine cost trends often track with morbidity and mortality. Those numbers improve when design helps people handle cattle correctly and keep the environment clean.

One of the first things to think about is cattle flow and operational efficiency. Individual sick or morbid cattle need to move calmly and efficiently from their home pen to the hospital system and into recovery pens or back to their home pens. That starts before a gate ever swings. A seamless facility design optimizes flow, provides efficiency and protects the cattle and the handlers. Every yard is slightly different so an in-depth understanding of the feedlot and their operation takes primary evaluation. Many start with an idea of where they think they want the hospital to be without giving a lot of thought to the above-mentioned movement efficiencies. Once a site plan is agreed upon, we then start with the hospital design layout.

Many facilities today have a system of treat and return policies with the goal of pulling an individual animal and getting them back to their home pen within two hours of being removed from their home pen. In this case, if drover alleys are available in the yard, we can set up simple treatment options in those alleys for cattle with a head catch, individual alley, weigh platform scale and method of recording. This is a more mobile or ambulatory system where we bring the medication to the individual alley. The advantage of this system is that animal health technicians that are checking the cattle do not have to trail the cattle long distances for treatments to be applied. Once treatments are applied, the animals are already in the zones of pens where they originated and can be returned to their home pen by the pen evaluation team or by the medics that are applying the treatment. If there are animals that require longer recovery, these animals can be loaded in a trailer or trailed to a more central hospital. The disadvantage of this type of facility is that we have to have a mobile medic and it too requires added communication between pen evaluators and the medics applying treatment. The design of this system is Figure 1.

The more standard hospital system in today’s feedlots requires pen evaluators to bring their individual sick or lame animals to the hospital either via trailing them or loading them in a trailer and delivering them to the hospital. Once delivered, I like to design facilities today that limit sorting of animals and maintain the block or zone of the yard they arrived from. This is keeping in mind that we are going to return some animals that same day or within 2 to 3

2

ZONE 3 ZONE 4

3 ZONE 4 ZONE 1 ZONE 2

Figure 1. Example of a pull and return to home hospital unit.

days post treatment. Therefore, the alleys or pens the cattle arrive in should have staging pens with water, shade, bedding and hay that the cattle can consume prior to treatment if needed. The staging pens are designed around the population of pulls that come from those zones on a daily basis. Typically, we provide around 25 to 30 sq ft of space for the animals in these staging pens prior to coming into the hospital. The alley from these staging pens to the hospital facility should be around 10 to 12

foot wide. Most individual hospital cattle will be handled on foot and not by horse or other means of moving the cattle. Wider alleys provide safety issues for the handler. The alley should lead to either a Bud-Box or a Bud-Tub, with BudTub being my preferred design choice whenever possible. Facilities should be a combination of open fencing with semi-solid swinging gates, which allow crews to move cattle forward in a swim-like fashion to the Bud-Tub without the use of additional prods. The less we fight cattle on the way in, the better our outcomes for the animal and handler. Cattle are unpredictable, which is why I strongly encourage pass through gates to allow handlers easy access in and out of the alley. Once cattle enter the Bud-Tub, they voluntarily travel down a straight, adjustable alley that is also open on the sides to the chute where treatments can be applied. The preferred chute will be recessed in the concrete so that there is no elevated step for the cattle to make to come into the chute or leave the chute. Today, I design a sediment capture under the chute with stationary scales so weight can also be captured. In the lead-up alley to the BudTub, in the tub itself, in the alley and directly after the cattle leave the chute, I like the flooring to be rubber mats. There are mats from several companies, and I recommend people call me for further consultation on this in the future. NuMat (figure 2) is a new company in the US, and I really like the texture and look of the rubber mat, and I think they will hold up well to feedlot conditions.

The chute area is another critical design point because it is where medicine meets management. Today we have cattle weighing 1500 to 1800 lbs, and having a chute that can easily handle these animals is imperative. Some chutes today make it difficult to handle

cattle of this size. Daniels Manufacturing and Arrowquip are two companies that have built their chutes to accommodate the current size of cattle. With the size of cattle, we are also seeing more and more foot health or musculoskeletal issues in yards. It used to be respiratory was our biggest challenge and it is true that it still is. However, musculoskeletal issues are rising and having the proper chute to deal with these issues is also important. Having a chute that also tilts so that feet can be easily looked at and treated is something we are designing today. Chute manufacturers are looking at ways of accommodating this by redesigning or adding methods to lift feet easier and safer for the animal health technician. Recently, I have worked with companies like Appleton Steel in Appleton, Wisconsin, to design something that feedlots can work with better. Arrowquip is another company that is working to address this. Silencer has a chute that will tilt, as do Brute and other companies. If you have questions on this, please feel free to call. Ensuring that a scale is in place to weigh all cattle for treatment is necessary. Guessing weight is costly. Underdosing lowers success while overdosing wastes product. A built-in scale also becomes a metric for evaluating recovery. Animals that are holding and not losing weight or gaining weight post treatment is a good sign. Weight loss signals the need to reevaluate our case to ensure we made the correct diagnosis or to provide additional therapy for the animal.

A hospital without proper record keeping is a poor hospital. Having chute-side computers and recording methods is important, but we do not want the hospital technician to have to make foolish steps to record. The more automated this can be for data capture, the better. Use of RFID tags for individual animal care is a method that can be linked to a visual identification number on the lot tag. Food safety and confidence in reporting is essential to maintaining this level of security in the beef industry. Today’s systems can automatically capture identification, weight and temperature as well as where the animal arrived from in a single catch. We can then enter manual lung scores for pneumonia severity, lameness scores for musculoskeletal injuries and severity to help further our assessment of treatment outcomes.

A hospital is only as good as its sanitation, and design decides how clean you can keep it. Hospital facilities should be washed down daily.

Having proper sediment drains to capture manure is important and having enough water pressure to make this a seamless effort and lessen the time constraint of cleaning will ensure this is done daily. If cleaning is difficult, it will not be done often enough. In staging pens and alleys, having them wide enough with concrete stem walls of 1 to 1.5 ft can aid skid loaders in cleaning and making the job simpler so manure can be pushed to sediment capture facilities to ensure all manure is captured from an environmental component. Ensuring that we have an equipment room for storage and cleaning is also important. We need to have an area where esophageal tubes for bloats, thermometers, hoof tools, etc. can be cleaned and disinfected daily. Good layout makes cleaning routine rather than optional, and those habits improve hospital recovery systems and metrics.

The hospital pens themselves are your intensive care unit. Provide cattle at least the same square footage they had at home with adequate bunk space and constant access to water. The best feed in the yard belongs in the hospital. Sometimes a flake of high-quality hay is the best probiotic to restart rumen function. Shade is not optional. Shade and shelter with good ventilation is imperative to recovery of sick or morbid animals. Cattle need areas of comfort to rest and recover if needed. In many hospitals pens today, this is lacking. Despite the current cost of the animal, it is more important that animal well-being and comfort takes center stage for these animals. Shade should be provided for the cattle at a minimum of 20 sq ft per animal in the pen. Today, I would concrete the entire hospital pen and ensure bedding is laid down in those pens for comfort and rest. Mud should never be an issue in a new or remodeled facility. Pens should also allow ration consistency. Keeping cattle on the same diet supports gut health and speeds recovery.

An adjacent overflow pen prevents crowding during high treatment times which otherwise creates treatment setbacks.

What makes a hospital system effective is attention to detail. Every element from how a gate latches to where the hose bib is located to the height of a man gate affects handling, sanitation and communication. When design makes handling easier, crews do a better job. When cleaning is simple, facilities stay clean. When cattle have space, shade, footing, comfort and ration consistency, they improve their chances of recovery and key performance measures follow.

Hospital management is one of my passions because it is where outcomes are determined and stewardship is visible. A well-designed facility helps us handle cattle calmly, diagnose accurately and treat effectively. It protects people, respects the cattle and protects your investment. Done correctly, hospital pens are not simply a place to hold sick cattle. They are where we give animals the best chance to recover and return to the home pen while keeping case fatality and treatment-to-death intervals in check and medicine dollars working where they should. We need to remember that medicine is a tool to help aid in the recovery of sick animals. The animal needs to heal themselves just like you and me. What aids most in recovery is the timing of identification of the symptoms of that sick animal, the handling and timing in which the animal is brought to the hospital, the care and accuracy in our diagnosis and treatment decisions, and most importantly, the rest, nutrition, hydration and comfort the animal receives while in the hospital facility.

If you are thinking about a new design, feel free to contact me via phone, text or email and I will be happy to go over what ideas I can offer you and how I can assist in your design or remodel of your facilities.

Dr. Kip Lukasiewicz received his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree in 1999 from Kansas State University. He is the owner of Sandhills Cattle Consultants, Inc. and a partner with Production Animal Consultation, LLC. Dr. Kip’s primary focus is feedlot consulting, animal handling, and facility design. Dr. Kip trained under the late Bud Williams and has worked and trained extensively with Dr. Tom Noffsinger utilizing Bud’s thoughts on low-stress cattle handling and caregiving. Dr. Kip along with Dr. Tom works and trains with over 20% of the US fed cattle industry and also travels to Canada training feedlot clients on low-stress cattle handling and caregiving. Dr. Kip resides in Farwell, Nebraska, with his wife, and they have two children. He is an active member of the Academy of Veterinary Consultants, Nebraska Veterinary Medical Association, and American Association of Bovine Practitioners.

Escrito por Russ Daly DVM, MS, DACVPM (Epidemiology), South Dakota State University

Encontrar un ternero muerto en el pastizal nunca es agradable. La pérdida del valor del ternero y la logística de su recuperación y su eliminación son lo suficientemente graves. Pero también existe la pregunta persistente de que fue lo que causó la muerte y cuantos más podrían correr con la misma suerte.

Esa pregunta a veces es difícil de responder en entornos de pastoreo. Los pastizales extensos hacen que sea un desafío revisar a cada animal todos los días. Las temperaturas cálidas del verano y los predadores que afectan la canal pueden empañar la capacidad del veterinario para identificar las lesiones reveladoras que resuelven el misterio. Además, hay muchas causas potenciales de muerte súbita en terneros en pastoreo, incluyendo rayos, envenenamiento por plomo, enfermedades respiratorias, roturas de úlceras estomacales y la enfermedad de la pierna negra.

Muchos productores se apresuran a descartar la enfermedad de la pierna negra como una de estas posibilidades. La enfermedad de la pierna negra es una de las causas de muerte más antiguas y reconocidas en terneros en pastoreo, pero aun así pocos productores han encontrado casos, por razones que explicaremos a continuación.

La enfermedad de la pierna negra progresa tan rápidamente una vez que aparecen los síntomas clínicos, tanto que estos mismos rara vez se notan: terneros muertos es, por mucho, la presentación más común de esta enfermedad. La causa de esta enfermedad es una bacteria llamada Clostridium chauvoei . Una característica importante de estos gérmenes es su capacidad de formar esporas, que son diseñadas para sobrevivir extremos ambientales como el calor y la sequedad. Estas esporas se encuentran en muchos entornos ganaderos, pero es en los pastizales donde los terneros son expuestos con mayor frecuencia.

Los terneros comen las esporas de la pierna negra mientas pastorean. Esas esporas viajan a través del intestino del ternero y son transportadas por los glóbulos blancos al musculo, donde permanecen latentes y probablemente nunca causen ningún problema. Sin embargo, en ciertos tenernos, cuando algo sucede que hace que cambie la oxigenación de ese musculo – un moretón, un esfuerzo extenuante o estrés, por ejemplo – las bacterias se activan, se multiplican y producen toxinas. Esas toxinas matan el tejido muscular, lo cual es bastante malo, pero también viajan por todo el cuerpo, interrumpiendo la función de los órganos vitales del ternero y causando una muerte rápida.

El daño muscular es prácticamente todo lo que el veterinario tiene para hacer un diagnóstico post mortem en un ternero afectado. A menudo, los músculos de las patas traseras albergan un área de necrosis (tejido muerto) que aparece de color marrón oscuro, llena de bolsas de gas y exuda un líquido maloliente de color rojo negruzco. Tal hallazgo sella el diagnóstico; el laboratorio de diagnóstico veterinario puede confirmarlo cultivando Clostridium chauvoei de esos tejidos en una placa de cultivo.

A veces, sin embargo, el daño causado por la bacteria de la pierna negra puede ser mucho más sutil en la canal afectada. El Laboratorio de Diagnóstico e Investigación de Enfermedades Animales de la Universidad Estatal de Dakota del Sur (SDSU, por sus siglas en inglés) ha documentado más de unos cuantos casos de pierna negra donde el daño del tejido es leve o difícil de ver. Este daño puede afectar al

corazón, al diafragma y la lengua (todos son tejido muscular, por cierto). Incluso las áreas sutiles de daño pueden favorecer el crecimiento suficiente de la bacteria y la liberación de su toxina para matar al ternero. La descomposición en el pastizal hace que detectar estas lesiones sutiles sea aún más difícil.

Un aspecto inquietante de la pierna negra es que a menudo afecta preferentemente a los terneros de crecimiento más rápido y con mejor musculatura; tal vez sus músculos sean más propensos a la tensión de oxígeno que ocasiona una cadena de eventos de la enfermedad. Por razones en su mayoría desconocidas, son los terneros, no las vacas ni los toros, los afectados por esta enfermedad.

Afortunadamente, la pierna negra es un problema muy prevenible. Las vacunas contra la enfermedad son numerosas y efectivas. La mayoría de las personas las conocen como vacunas de “7 vías” u “8 vías” que incluyen protección contra otros miembros de la familia Clostridium , como la enfermedad de sobrealimentación y el tétanos.

La vacunación de los terneros antes de sacarlos a pastar es un método preventivo comprobado contra la pierna negra; los brotes son raros en los hatos vacunados. Las etiquetas de las vacunas contienen instrucciones para administrar una dosis de refuerzo entre 3 y 6 semanas después de la primera administración; en ciertos pastizales problemáticos, este requerimiento de refuerzo podría resultar importante. El uso generalizado de estas vacunas ha hecho que la enfermedad de la pierna negra sea poco común hoy en día.

Los productores que no vacunan regularmente a los terneros contra la pierna negra al inicio de la temporada de pastoreo están esencialmente “jugando a los dados”, ya que la mayoría de los pastizales albergan las esporas bacterianas. Si se encuentra en esta categoría, es una buena idea hablar sobre un programa de vacunación con su veterinario. Y explorar esos pastizales para detectar los desafortunados, pero ojalá raros, casos de muerte de terneros aumentara las posibilidades de que usted y su veterinario determinen la causa.