With a mix of forward and backward crops in the ground this season, early agronomy needs careful tailoring to their potential, ProCam regional agronomists explain.

Compared to last year when cabbage stem flea beetle (CSFB) and poor establishment meant half his winter oilseed rape (WOSR) was written off, WOSR has been a big success so far this season, says northern region technical manager, Nigel Scott.

More WOSR has been planted, he says, and few if any fields are likely to be write-offs. However, there are polar opposite situations with winter wheat.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 2

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 1

With winter wheat, Nigel Scott says fields range from forward early September-drilled crops to later-drilled backward ones – not helped by cold wet soils and low vigour in over-yeared seed.

“Most direct drilled wheat was also slow emerging,” says Nigel, “and we’ve seen big differences between varieties in speed of development.

“We’ll be looking at promoting tillering in backward wheat – drawing on plant growth regulators (PGRs), biostimulants and early nitrogen (N). After all the autumn rain, it will be important to measure the amount of soil N available. If it’s low, provide more. If canopies are variable, consider variable rate N.”

To supplement prilled N, Nigel suggests applying endophyte bacteria, which fix N inside the plant (see pages 4-5). He says growers reported improved crop greening using this approach last year.

“It takes a lot of N to build biomass, so don’t reduce the first third of the season’s N dose. But if applying an endophyte at T0 or T1 provides 30kg N/ha, it can help mitigate poor granular N uptake later. There’s also the carbon footprint of prilled N to consider, and if the imported fertiliser carbon tax comes in, this technology needs seriously considering.

“Also be mindful of micronutrient deficiencies. Some winter barley drilled early on light land is likely to need manganese as soon as possible.”

Nigel Scott says growers have reported improved crop greening where N-fixing endophyte bacteria have been applied.

Although 90-95% of his winter cereal area has been drilled, Pryse Whittal who advises in Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Shropshire, is expecting a lot of backward winter wheat going into spring, after many crops were not drilled until November.

He agrees early N will be important for tillering plus rooting. Variable rate N will be appropriate in some scenarios, plus biostimulants such as Zodiac and Incite, he suggests.

“We can still have decent yield from later-drilled crops because seed rates should have been increased. Statistically, they should be under less Septoria pressure, although more prone to yellow rust. I’ll be mindful of brown rust after last season’s pressure, but hopefully that won’t repeat.”

With WOSR drilled both early and late in a bid to avoid peak adult CSFB migration, Pryse says again there are forward and backward crops – some with only 4-5 leaves.

“If forward crops retain biomass, they might not need N and sulphur (S) until March. But with backward crops, we’ll look to apply at the earliest opportunity in February – not large amounts but enough to push them forward. Rains could mean soils are low in readily-accessible N, so there could be a case for phosphite treatment to stimulate roots.

“If late autumn fungicides weren’t applied, monitor crops and be prepared to apply one; light leaf spot could appear between January and March. The biostimulant or foliar nutrition could be applied at the same time.

“Ahead of potato planting, PCN testing and soil tests for nutrient availability will be needed, especially on unknown rented ground. And cover crop destruction needs planning. Some brassica species need quite high glyphosate doses. If foliage has been damaged by frosts, there’ll be reduced leaf area to take up lethal doses of glyphosate – which is required to control species with large tap roots or extensive roots systems.”

Forward and backward winter oilseed rape crops need different management ahead of spring, says Pryse Whittal.

boron, sulphur and molybdenum to ensure crops have everything needed for stem extension.

“A key lesson from last season’s cold spring was how much maize benefited from being grown under film. Film supply will be tight this season, so it’s important to order early. For open grown situations, we have two exciting new maize varieties, Marcopolo and Jardinero,” she adds.

Advising in Suffolk and Essex, Luke Stevens also saw few winter cereals drilled in September, with most drilled during the late October to mid-November window, then more wheat drilled after roots. However, only 80% of his winter wheat area had been planted before Christmas.

“How crops are managed will depend on the weather. If it’s dry, Septoria pressure could be reduced. But we saw last year how it can increase quickly if it’s wet and mild, even in late plantings.

After September drilling was curtailed, many winter cereals were not drilled until November in the South West, says agronomist Emma Dennis, which has created both positives and negatives.

“While crops drilled in September or the first week of October are likely to see intense Septoria, a benefit of later drilling should be reduced Septoria pressure, especially on more resistant varieties,” Emma says.

“Another positive should be reduced barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV), although day degree temperatures accumulated quickly in the mild autumn, so we can’t be complacent. In future, we could see increased interest in growing BYDV resistant varieties.”

On the negative side, Emma says later-drilled crops will need careful nursing, including nutrition. “Cold soils make crops slower to put roots down. So consider a phosphite treatment before T0 to promote rooting, which can help crop resilience in adverse spring weather.”

By contrast, there are some large WOSR crops, says Emma, and CSFB numbers have been low, possibly because the wet summer affected adults.

“As soils cool, propyzamide can be applied where grass weed pressures determine the need; and making sure to comply with label restrictions. Larger crop canopies can shade out grass weeds, so conditions need to be ideal. Nutritionally, focus on

“Similarly, although last season’s intense brown rust was hopefully a freak event, there are lessons from it, particularly with the popularity of Crusoe. If you see rust, fungicide programmes need adapting accordingly,” he adds.

“Also, there’s no doubt the germination pattern of blackgrass has shifted in my area, so later drilled crops also need checking.”

With WOSR, Luke says most has established well, producing large canopies with little CSFB. “We’ll assess green leaf area and tailor N accordingly,” he adds.

With a lot of wheat drilled in late August to mid-September, be aware of heightened Septoria tritici risks, urges Scotland’s regional technical manager, Alistair Gordon, especially with so much Skyscraper grown for distilling.

“Wide temperature fluctuations in the region which put crops under stress can also make them more vulnerable,” he says, “although hopefully yellow rust reported further south will be checked by frosts.

“By April, early-drilled crops have been in the ground half a year or more, so targeting overwintered disease at T0 is key. It’s not only more effective to prevent disease building, but often cheaper than trying to cure it. Creating a healthy crop canopy with nutrition also helps resilience,” he adds.

Adjusting N applications will help regulate the growth of forward wheat, says Alistair, but PGRs will also be important. There are also some big weeds in crops, he says, requiring prompt treatment in spring.

“Some WOSR crops were also over a foot tall by Christmas, and large canopies have a lot of decaying foliage in the base, which is an infection source. So consider combined PGR and fungicide treatments.

“To help customers manage busy spring workloads, Robertson Crop Services offers contract spraying – running six self-propelled sprayers from our Invergordon and Cuminestown depots.”

“With late-drilled wheat, to encourage tillering I can foresee a lot of rolling being needed in spring, plus use of Zodiac and early N. Lodging risks also need assessing in spring, but trinexapac PGR applied at T0 also helps tillering.”

Fortunately, Luke says full stacks of residual herbicides have generally worked well in winter cereals against blackgrass and rye-grass. “Towards spring, we’ll assess surviving weed populations and apply contact herbicides as appropriate. Resistance needs factoring in, but even if these only give 15-20% control, that can be worthwhile.

By April, early-drilled crops have been in the ground half a year or more, so targeting overwintered disease at T0 is key,

With multiple products available aimed at boosting nutrient availability and nutrient use efficiency in cereals, which do you use and when?

Apply bagged nitrogen (N), phosphate, potash, sulphur and trace elements as needed, and crop nutrition is sorted. While that might have been traditional thinking, things have evolved, says ProCam Head of Technical Development, Rob Adamson. Today, environmental, weather and cost pressures, and realising that more can be done to boost crops, have fuelled interest in biological treatments to support traditional fertilisers, he says. And with talk of an imported fertiliser carbon tax, he suggests these treatments could hold increased appeal.

“We can’t completely replace bagged N,” says Rob. “But recent seasons have highlighted the role for these treatments when soil N is leached, when bagged N becomes expensive, or when there’s a need to boost backward crops.

“Our trials have examined whether biofertilisers can help maintain yields if N availability is reduced, or improve yields with a standard N programme, but also whether biostimulants can improve the efficiency with which plants use the nutrition available.”

Rob

says it’s not about choosing either a biostimulant or a biofertiliser, because they fulfil different roles.

Reviewing biofertilisers, Rob says ProCam has tested a range of N-fixing bacterial treatments, but two that stand out are the Rhizobacteria, SR3, and the endophyte spray, Encera.

“Rhizobacteria fix N in the soil and feed it to the roots. Endophytes fix N inside the plant. It takes a bit of getting used to applying bacteria, but these types of treatments can help mitigate both N cost and reduced N availability.

“While SR3 is applied to the soil at T0, Encera is applied with the T1 foliar spray and forms a symbiotic relationship inside the plant’s cells. The plant gives the endophyte sugar, the endophyte gives the plant N. We believe Encera can supply around 30 kgN/ha. If bagged N application is delayed or it’s too dry for N uptake, it can help feed the plant.

“If considering these treatments, it needs stressing that applying the first traditional N dose remains critical for tiller numbers and yield. So in trials, we only look at reducing the second and third N doses,” he adds.

For T2, Rob says ProCam has researched a liquid treatment, Pro+ N-Viron PCA. Although not a biofertiliser, he says this urea polymer gets N into the plant efficiently, with 20 l/ha supplying the equivalent of 40 kg/ha of bagged N. It also contains a biostimulant – pidolic acid – which further enhances the efficiency of the applied N, he notes.

“You wouldn’t use all three products. But with 30 kg N/ha coming from SR3 or Encera, plus use of Pro+ N-Viron PCA, you can see how they can reduce bagged N reliance.

“Another aspect is that end markets are increasingly seeking produce with reduced carbon footprints, so these treatments could play a role here.”

Assessing biostimulants, Rob says different biostimulants work in different ways, and the key is to understand this so they can be used at a growth stage when their mode of action brings greatest benefit.

Prior to T0, he says a prime aim is to encourage rooting to improve access to soil nutrients and moisture, with poor rooting imposing an early limit on yield. Brown seaweed extracts are very effective at root enhancement, he notes, but a treatment that combines seaweed extracts with amino acids has been found to increase root

“You wouldn’t use all three products. But with 30 kg N/ha coming from SR3 or Encera, plus use of Pro+ N-Viron PCA, you can see how they can reduce bagged N reliance. Another aspect is that end markets are increasingly seeking produce with reduced carbon footprints, so these treatments could play a role here.”

and shoot growth more than seaweed extract alone.

“At T0 there’s still time to influence rooting, and phosphites are useful here. They induce rooting by increasing cytokinin, but also increase the activity of a plant enzyme involved in N utilisation. Pidolic acid provides a complementary mode of action, and the product Incite, which combines both materials, has been shown to boost rooting more than phosphite alone.

“At T1 the aim is still to boost N assimilation but also photosynthesis. This is where pidolic acid comes into its own. Pidolic acid-treated crops generally have a higher chlorophyll content, and applying it around GS31-32 has given the biggest yield response. The product Twoxo Pro combines pidolic acid with the metabolite 2-oxo and molybdenum. Our trials show that application at T1 helped bridge the yield gap where N supply was reduced. It gets the crop to work harder to access and use the N available.”

“Molybdenum is a key element in N assimilation,” explains Rob, “being required by the enzymes involved in this process, which is why molybdenum deficiency can appear similar to N deficiency. With pidolic acid and 2-oxo both increasing the speed and efficiency of N assimilation, the molybdenum component ensures this doesn’t become a limiting factor.

“By the flag leaf timing, the emphasis turns to feeding the flag leaf and maximising photosynthesis – as wheat’s biggest ‘solar panel’. This is where the Pro+ N-Viron PCA is so effective as both a N source and a biostimulant.

“Again, you’re not going to use all biostimulants. The key is to cherry pick them according to crop needs or limitations at different times of the season. Enhancing rooting will benefit virtually any crop. Beyond that, their use needs to be more tailored.”

Performance of the biostimulant Twoxo Pro with three different total nitrogen doses (120, 150 and 180kgN/ha) in ProCam trials

ProCam’s trial tested an array of aclonifen treatment protocols

ProCam has hosted an herbicide trial at Cawood in North Yorkshire to understand how best to use aclonifen to control weeds in carrots. ProCam Field Veg Agronomist, George Dewhurst, explains more.

“Although aclonifen has been around for a while, it’s a newcomer in terms of its approval for use in carrots and parsnips,” George says. “There’s therefore little in the way of independent data to define how it should be used alongside other modes of action, so we have done our own research to understand how and when it should be included.”

The Cawood trial tested an array of treatment protocols with the following aims:

1. To understand the impact of aclonifen on crop safety at different rates and timings.

2. To understand how aclonifen can complement current herbicide programmes.

3. To develop an effective commercial programme that delivers best crop yield.

Two pre-emergence treatments were tested: the first consisting of aclonifen, pendimethalin and clomazone, the second adding metribuzin into the equation. Three post-emergence treatments were also tested: these consisted of low doses of aclonifen, prosulfocarb and metribuzin applied at the peri-emergence, first true leaf and second true leaf timings.

“Timing is everything when it comes to applying herbicides to vegetable crops,” George continues, “not just in terms of maximising weed control, but also in terms of crop safety. Any damage caused by herbicides will have a direct impact on yield, but all too often I see crops which have been adversely affected by over-ambitious programmes.”

The wet spring meant the trial was drilled at two different timings, effectively resulting in two parallel trials running 10 days apart.

“In both cases we saw similar results, so the conditions actually helped to corroborate our findings,” George describes. “The different treatments clearly displayed varying levels of weed control and crop performance.”

“The most important thing we learned was that repeated low doses of multiple active ingredients, including aclonifen, achieves the best level of weed control, with the mantra of ‘little and often’ providing the most succinct summary of the trial’s findings. We look forward to sharing our findings with customers as the new cropping cycle unfolds.”

Low doses of multiple active ingredients, including aclonifen, achieves effective weed control and crop safety in carrots, explains George Dewhurst.

For Buckinghamshire farmer, Steve Lear, taking on new land provided a perfect reason to adopt precision nutrient application.

Historically, Steve Lear of HB and LJ Lear has farmed around 730ha of combinable crops and grassland in Buckinghamshire.

But when the business acquired a further 360ha in Dorset in 2023, there was a need to understand the nutrient status of the new land.

Moreover, being in the Sturminster Marshall catchment area, Steve says there was a need to be sensitive to risks of nitrates entering groundwater. With the £27/ha SFI incentive available, he decided tailored variable rate nutrient application was the way to go.

“The Dorset land is good ground, so we thought we’d do the best job possible,” explains Steve. “We had to buy new kit when we took on the land, so we bought a variable rate spreader.

“This is the first time we’ve used variable rate application. Being in the catchment area was the main reason, but the SFI helped.”

Working with his ProCam agronomist, Paul Gruber, Steve used the new FieldSense precision farming service – beginning with

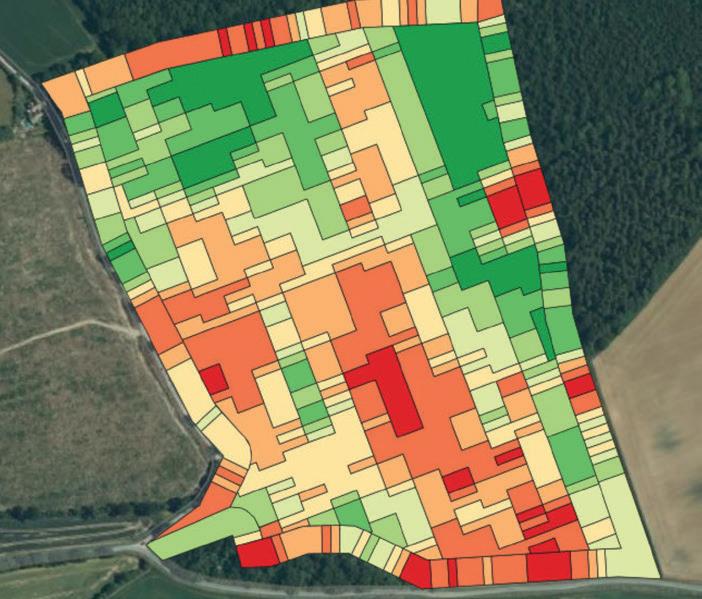

Variable rate spreading plans illustrate the wide range of N doses needed to help ‘rebalance’ WOSR growth across a field, says ProCam’s Paul Gruber – here from 145 (dark green) to 348 kg/ha (dark red) of fertiliser product.

variable rate nitrogen (N) application on winter oilseed rape (WOSR), which uses satellite NDVI measurements of the growing crop.

“We did about 100ha in total,” says Steve. “Greener parts of the crop received less N. Previously the land had outdoor pigs on

“

Paul Gruber says FieldSense works by dividing fields into grids. For Steve’s P, K, Mg and pH analysis, 300 soil samples were taken from field grids during September. From these, spreading plans were developed.

“There were quite high P reserves in the soil, so we don’t need to apply P to those parts of fields. Given the catchment area, additional P certainly wouldn’t be promoted.

“For K, there aren’t many areas of fields that aren’t getting any. Lower areas will benefit from building reserves up.

“Meanwhile, magnesium mapping showed some low indices, so we’ll probably marry these with spring tissue testing.

“Avoiding unnecessary nutrient use with variable rate applications offers potential savings and is environmentally sound. With traditional W pattern field sampling, high and low indices can be masked. And the FieldSense partnership approach makes things simpler for growers,” Paul adds.

it, so there was quite big variability. But the conclusion was it worked well. It evened the crop up. We used the same amount of N but targeted it better.”

Now, FieldSense is being extended to other fields in the Dorset rotation, of winter wheat, winter beans and spring barley, with soils tested last autumn for phosphate (P), potash (K), magnesium (Mg) and pH.

With the soils over chalk, no lime was required. However, variable rate K will be applied in spring and variable rate N, following variable rate P over winter.

At the touch of a button, FieldSense has also allowed modelling of different offtake scenarios – comparing the effects of chopping straw versus baling it on soil P and K levels and taking into account the financial value of the bales. “Beans were not worth baling, but the others were,” says Steve.

“FieldSense has been easy to use. Dorset has been a good test. It’s highly likely we’ll also use it in Buckinghamshire, given the results.”

Some maize yields were a little underwhelming in 2024 thanks to a combination of lower-than-normal temperatures and a lack of direct sunlight hours during the summer.

These sub-par growing conditions, combined with a wet spring which delayed drilling and a wet autumn which hampered harvesting, meant some crops performed worse than expected in terms of dry matter yield, starch content and energy value.

As such, some within the industry are predicting the 2025 maize area will increase as livestock producers and growers for AD compensate for reduced stocks in silage clamps. Only time will tell how this year’s growing season unfolds, but growers can mitigate some of the risks associated with weather volatility by using a starter fertiliser and/or biofertiliser to improve crop performance and consistency.

“Maize is very efficient at utilising nitrogen and can produce a high dry matter yield from a relatively low fertiliser input,” explains Simon Montgomery, Technical Lead for ProCam’s Field Options Performance Seeds. “However, maize does need sufficient P and K to enable crops to develop a strong root and to get up and out of the ground rapidly, with the highest yielding varieties also requiring additional N to enable them to reach their true yield potential.”

As an alternative to applying a higher rate of conventional granular or foliar N, more

maize growers are using biofertilsers to give crops access to this additional nitrogen.

“Applying a biofertiliser spray treatment such as Encera which contains endophyte bacteria that fix atmospheric N and make it available inside the plant has proven successful in trials as a complementary source of N,” Simon describes.

Trials carried out by ProCam over the last three years have shown that maize crops treated with Encera not only looked healthier, but also produced an additional 3.6 tonnes of dry matter per hectare compared to crops treated with a standard application of conventional N. Metabolisable energy yield was also boosted by an average of almost 5,000 MJ/ha when Encera was used to replace 25kg of N.

“Compared to using 25kg of additional, conventionally applied N, Encera has produced a consistent improvement in yield and energy yield,” Simon explains.

“The trials have clearly indicated that Encera reliably increases nitrogen availability, and in doing so enables plants to produce a greater volume of fresh weight and dry matter,” Simon continues.

“In fact, compared to using 25kg of conventionally applied N, Encera produces a consistent improvement in yield and energy yield which translates to more milk and meat produced on farm. And, because the N produced by the Encera bacteria remains available to the plant even in drought conditions, crops will still yield well even in a difficult season.”

Using Encera to push a high-yielding crop such as maize also complies with the RB209 Nutrient Management Guide, Simon adds, “so it’s a win-win situation, especially as the boost in metabolisable energy yield means more milk, more biogas, or more meat production.”

To find out more about any of the products mentioned, or for more information about ProCam’s wider range of forage crops, download a copy of the latest Field Options Performance Seeds catalogue at www.field-options.co.uk