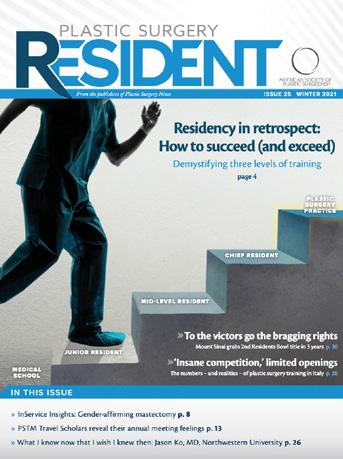

Four plastic surgeons share their internal struggles – and offer solutions

» OSU reclaims the Residents Bowl crown Ohio State triumphs in Boston for its 3rd overall title page 32

Your senior resident is struggling – what now?

'Dear Abbe' offers mechanisms of support page 26

IN THIS ISSUE

» Renowned hand surgeon Nicholas Vedder, MD, reveals his best moments, motivations p. 24

» InService Insights: Congenital ear anomalies p. 18

» International perspective: The view of plastic surgery from Mexico p. 27

Syndrome

Imposter

From the publishers of Plastic Surgery News

From the publishers of Plastic Surgery News ISSUE 29 | WINTER 2023

SAVE WITH ADVANCE REGISTRATION RATES THROUGH FEB. 19 PlasticSurgery.org/SpringMeeting REGISTER TODAY AESTHETIC • BREAST • PRACTICE MANAGEMENT A VIRTUAL MEETING

Table of Contents

Imposter Syndrome: Combatting an insidious mindset

Plastic surgeons from varied levels of the specialty reveal how they deal with “imposter syndrome.”

What I Know Now: Lessons from a plastic surgery leader

8 Michael Neumeister, MD, reveals the traits possessed by excellent residents.

Program Peek:

From surgical clamps to the “green bible,” Temple has hosted specialty giants and their innovations.

Faculty Focus:

Christine M . Jones, MD

Residents would do well to keep a keen eye, “go the extra mile” and find a trusted mentor. Message

takes pride in its enriching training program – and in its resident-engagement efforts. 24

All the entertainment you need can be found in this history-rich city.

InService Insights

This regularly addressed exam condition undergoes a review from categories through treatment.

The real work begins after methodically ruling-out any life-threatening injuries during the initial evaluation.

The most-common form of breast reconstruction following mastectomy is highlighted through these 10 articles.

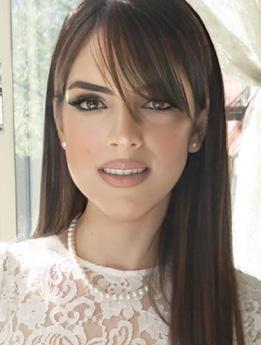

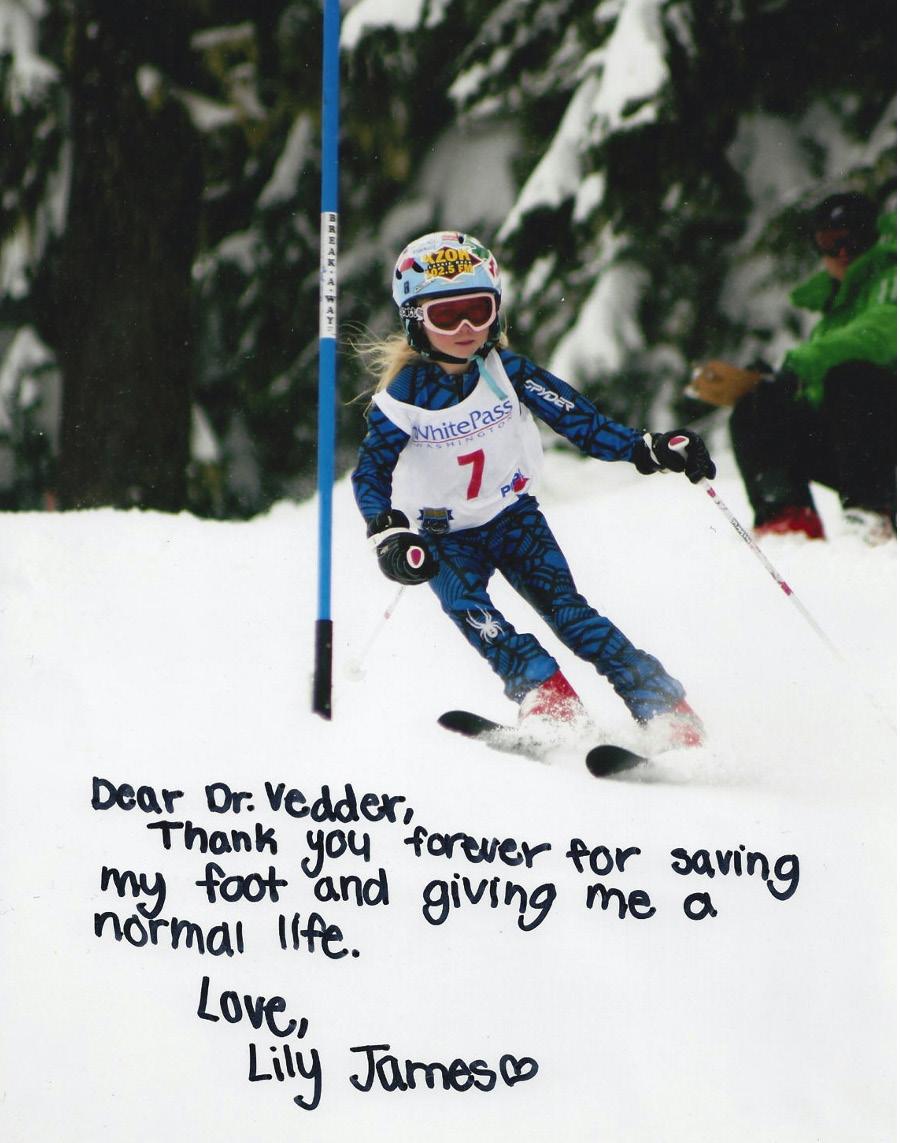

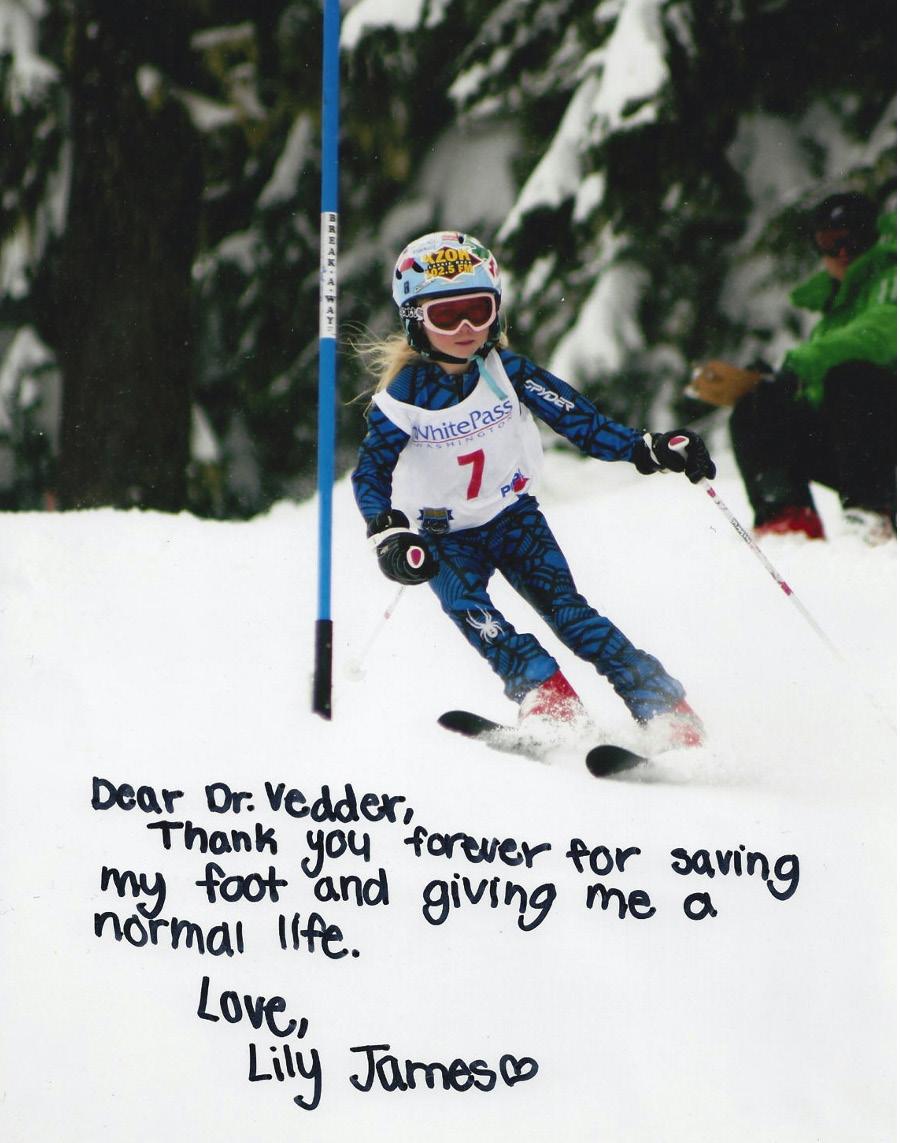

Nicholas Vedder, MD, discusses the subspecialty’s advances – and the pediatric case close to his heart.

Dear Abbe:

My senior resident is struggling

column offers ways subordinates can help struggling superiors.

Daniel De Luna Gallardo, MD, describes how the specialty and training programs have grown in recent years

Travel Scholars speak:

of PSTM22 appreciation

Resident travel scholarship winners describe benefits gained by attending Plastic Surgery The Meeting.

Residents Bowl 2022: Tough battles and worthy competitors

32 Edward Davidson, MD, and Raj Sawh-Martinez, MD, MHS, reflect on the tournament.

Ohio State brings the trophy home again .

earns the program’s third Residents Bowl title. Message From Your Resident Representative: Update on Goals and Initiatives

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023

Vol.7 N o.1

The mission of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons is to support its members in their efforts to provide the highest quality patient care, and to maintain professional and ethical standards through education, research and advocacy of socioeconomic and other professional activities.

ASPS PRESIDENT

Gregory Greco, DO | plasdoc39@msn.com

EDITOR

Russell Ettinger, MD | retting@uw.edu

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Joseph Lopez, MD | joeyl07@gmail.com

Megan Fracol, MD | mfracol@gmail.com

SENIOR RESIDENT EDITOR

Olivia Abbate Ford, MD | oford@partners.org

RESIDENT EDITORS

Aradhana Mehta, MD, MPH | aradhana.mehta@unlv.edu

Alexis Ruffalo, MD | aruffolo57@siumed.edu

Mark Shafarenko, MD | mark.shafarenko@mail.utoronto.ca

INTERNATIONAL RESIDENT EDITOR

Daniel De Luna Gallardo, MD | daniel.delunag@gmail.com

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT

Michael Costelloe | mcostelloe@plasticsurgery.org

STAFF VICE PRESIDENT OF COMMUNICATIONS

Mike Stokes | mstokes@plasticsurgery.org

MANAGING EDITOR

Paul Snyder | psnyder@plasticsurgery.org

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR

Jim Leonardo | jleonardo@plasticsurgery.org

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Jun Magat

ADVERTISING SALES

Michelle Smith (646) 674-5374 | Wolters Kluwer Health

Plastic Surgery Resident (ISSN 2469-9381) is published four times per year and distributed free to members of the ASPS Residents and Fellows Forum and plastic surgery training programs. Letters, questions or comments should be addressed to: Editor, Plastic Surgery Resident, 444 E. Algonquin Road, Arlington Heights, IL 60005.

33

Olivia Abbate Ford, MD, provides a roadmap to the future and heralds the new Residents Council Report.

The views expressed in articles, editorials, letters and other publications published by Plastic Surgery Resident (PSR) are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of ASPS. Acceptance of advertisements for PSR is at the sole discretion of ASPS. ASPS does not guarantee, warrant or endorse any product, program or service advertised.

ASPS Home Page: plasticsurgery.org

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Temple University

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

12

Director:

Patel, MD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 Temple

Hours

Philadelphia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

from the

Sameer

University

in:

ear anomalies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Congenital

Consult Corner: Facial-nerve

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

trauma repair

Journal Club: Alloplastic

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

breast reconstruction

22

Plastic

Perspectives: Hand Surgery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Surgery

24

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

International

Dispatch

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Advice

Perspective:

from Mexico

Voices

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

29

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

OSU

.

35

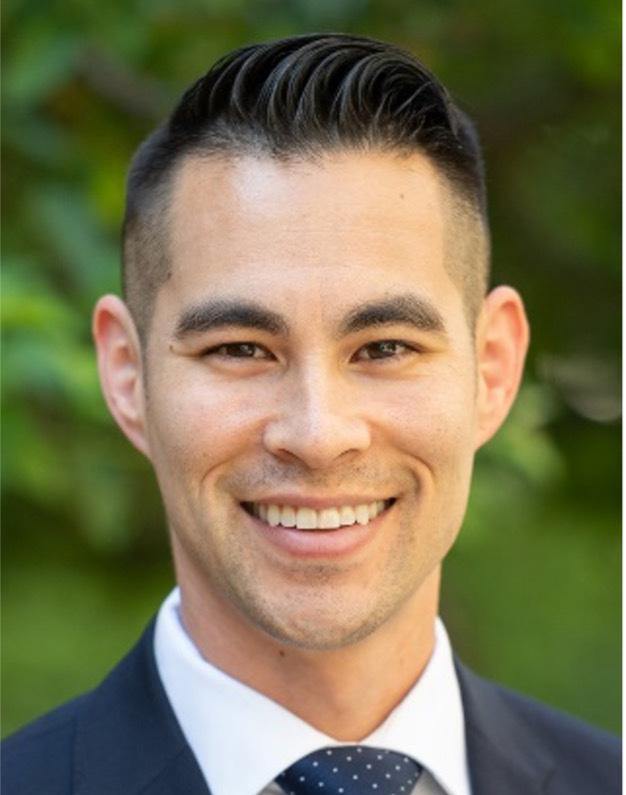

Russell E. Ettinger, MD Chief Medical Editor Plastic Surgery Resident Seattle

A note from the editor

Happy New Year and welcome to the Winter 2023 issue of Plastic Surgery Resident (PSR)

In our first issue of the year, we would like to start off by recognizing our outgoing team of Resident Editors Michael Hu, MD (University of Pittsburgh); Harry Siotos, MD (Rush University), Ravi Viradia, MD (University of Tennessee), and our International Resident Editor Monica Zena, MD (Italy). Thank you all for your hard work and curation of some amazing pieces for our readership over the past year!

We would also like to welcome our new incoming Resident Editor team: Aradhana Mehta, MD, MPH (University of Nevada, Las Vegas); Alexis Ruffolo, MD (Southern Illinois University); Mark Shafarenko, MD (University of Toronto); and International Resident Editor Daniel De Luna Gallardo, MD (Mexico). We also welcome Olivia Abbate Ford, MD (Harvard University), the new Resident Representative to the ASPS/PSF Board of Directors and Senior Resident Editor. Olivia will be your voice within ASPS/PSF; so be sure to reach out to her at oford@partners.org with any feedback, concerns or ideas.

This issue of PSR features a cover article evaluating imposter syndrome and its implications for plastic surgery training and practice. We highlight Temple University and the city of Philadelphia in our Program Peek, and our recurring pieces feature topics on congenital ear anomalies, facial nerve injuries and alloplastic breast reconstruction. Our international perspective highlights residency training in Mexico, and we hear from Dr. Ford on her plans for the year as the newly instated resident representative. Be sure to check out our features that also include valuable career and life insights from The PSF past Presidents Michael Neumeister, MD, and Nicholas Vedder, MD, who are also prominent plastic surgery program chairs.

Last but not least, we recap the exciting 2022 Residents Bowl with pieces from YPS Residents Bowl Subcommittee Chairs Edward Davidson, MD, and Raj Sawh-Martinez, MD, MPH – and from the Residents Bowl champions, The Ohio State University, who took home the hardware and a year’s worth of bragging rights.

Thank you to you, our readers, and to our team of editors and the ASPS production staff. We hope you enjoy the read! |

4 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Winter 2023

IMPOSTER SYNDROME

Silencing the inner voice that whispers ‘fraud’

By Michael Hu, MD, MPH, MS

By Michael Hu, MD, MPH, MS

This issue’s cover story delves into the concept of “imposter syndrome” –defined by one source as “a psychological occurrence in which an individual doubts their skills, talents or accomplishment, and has persistent, internalized fears of being exposed as a fraud” – and how that condition impacts all of us as we progress through residency training, fellowship and beyond. We bring insights from four exceptional individuals, all at different levels of training and practice – and all of whom I personally know to be outstanding clinically and technically. Based on their aptitude and propensity for excellence, one might assume they have a very low incidence of “imposter syndrome” – yet no matter how skilled, prepared and diligent we are, imposter syndrome and its manifestations are a universal experience for anyone within the realm of medicine and surgery. We’ve all felt and experienced it and, unfortunately, the implications of imposter syndrome don’t magically disappear once we complete surgical training.

By examining imposter syndrome in more detail as it pertains to plastic surgery training and beyond, we hope our readers find solace and comfort in the connection to these shared experiences. I would like to thank each of our

authors for their candid and thoughtful responses on a topic that’s inherently challenging and vulnerable to write about – but one that we all will find immensely relatable.

Russell E. Ettinger, MD Chief Medical Editor, PSR

Russell E. Ettinger, MD Chief Medical Editor, PSR

How has imposter syndrome manifested itself in you?

It’s been an underlying theme during residency. It was a more constant feeling at the beginning of residency, but it’s become less frequent as I’ve gained more experience and confidence in my skills and reframed my thinking. However, it still occasionally affects me whenever I come home from a rough day – wondering whether I made a mistake or feeling as though I wasn’t perfect. Feelings of imposter syndrome are particularly strong when I compare myself to others.

Alison Bae, MD PGY-6, University of Washington, Seattle

How do you define imposter syndrome?

Imposter syndrome means feeling as though I’m not skilled, knowledgeable or good enough to be where I am. Specifically that I’m not accomplished or talented enough to be a plastic surgery resident, let alone one who’s about to graduate. It comes with feeling less successful than my peers. It’s thinking that luck – not my achievements – was responsible for me getting into medical school and residency, and hoping that people don’t discover that I got in by mistake.

How did you handle these feelings –and how did you move beyond them? Several things helped me throughout residency. During my intern year, I went to a therapist who was made available through our residency program, because these feelings of imposter syndrome were weighing heavily and I felt like I was floundering. Something as simple as forgetting to look up a patient’s drain output for rounds made me feel like I wasn’t good enough. My therapist helped me realize that one mistake or one bad day does not make me a bad resident. It’s normal to make mistakes, and the most important thing is to learn from them as opposed to letting

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 5

them define you as a person. Talking to a therapist helped me realize that I had these negative thought patterns and taught me strategies to break these cycles.

Whenever I have feelings of imposter syndrome, I tell myself that I’ve already been vetted; I graduated from a top-tier medical school; and I’ve nearly completed residency at one of the best programs because I have what it takes. I don’t have to prove that I belong because I already belong. I remind myself of the things that I’m good at instead of focusing on my weaknesses. I use the positive feedback that I’ve received from mentors to bolster these thoughts.

It helps that I talked to my peers and learned that imposter syndrome is not just from within – that systemic biases against women and people of color are contributing factors to feeling out of place. Sharing our experiences and knowing that other residents feel the same way normalizes things. Also, my confidence increased as I gained knowledge and improved technically, allowing me rise above imposter syndrome.

What advice do you have for residents who experience imposter syndrome?

Recognize that everyone experiences some varying degree of imposter syndrome and that it’s not unique to you. Talk to your peers, seniors and mentors about it and learn the methods they used to move beyond it. Seeking expert advice from a therapist can give you outside perspective and help you learn new strategies. Residency is about becoming a plastic surgeon – so learn from your mistakes and learn from your peers, and imposter syndrome will get better over time.

Calvin Young, MD Private practice, Rochester, N.Y.

How do you define imposter syndrome?

Imposter syndrome is that quiet voice of frequent self-doubt. It rears its ugly head during times when I’m alone with my thoughts. It asks questions such as: “Are you sure this is the right plan?” or “When are they going to find out I don’t belong here?” It makes statements such as “You’re not good, just lucky” or “You’re one slip-up away from the walls crashing down.”

How has imposter syndrome manifested itself in you?

I trained in general surgery for seven years followed by three years of plastics residency. As a chief resident in general surgery, you’re running traumas or codes, managing care of the critically ill and doing procedures you’ve done hundreds of times.

When I started training in plastic surgery, all that confidence went away and I was basically starting over. Coupled with that, I entered a class of some very smart people who had much more experience and knowledge than I. Sure, I could operate, but most of the procedures were new to me and my colleagues were speaking a different language of surgical terminology. It was a real “sink or swim in the deep end” moment.

Once training was over, I took a job as the only plastic surgeon in a dermatology group. I could no longer walk down the hall to the attendings’ offices or into the resident room to bounce ideas or plans off anyone. Now I was

the attending. “Who are you kidding?” I thought. Even as I answer this question, I’m waiting for my board-certification results. “Who am I to write something about helping overcome imposter syndrome? I might well actually be an imposter!”

How do you handle these feelings – and how do you move beyond them?

I don’t know if you ever really move beyond it – maybe when you’ve seen it all, you can. Sometimes I wonder if this feeling is just part of me and how I prepare for each case. I still spend a lot of time thinking about consults, reviewing notes and exams, and writing down my exact surgical plan for each case. With each great outcome or thankful patient, though, your confidence grows a little bit. Learning to say, “No, I’m not the surgeon for you” is also very powerful and helps reinforce your confidence in your surgical decision-making.

What advice do you have for residents who experience imposter syndrome? During times of self-doubt, I find it helpful to talk to people who’ve been there. Sometimes it’s people in medicine who’ve been there in surgery – or even perspectives from other specialties.

I’m lucky enough to be married to a pediatric endocrinologist who’s been practicing for years. She went through it; I think we all do. For what it’s worth, I’ll be happy to chat if you need someone to talk you down.

IMPOSTER SYNDROME / continued from previous page

ASPS member Daniel Driscoll, MD (left), and Ukrainian surgeon Artem Posunko, MD (right), perform surgery on a pediatric burn patient while anesthesiologist Gennadiy Fuzaylov, MD (center), administers the anesthetic.

6 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Summer 2022

Shanique Martin, MD PGY-3, University of Washington, Seattle

How do you define imposter syndrome?

Imposter syndrome is this looming thought of inadequacy and self-doubt – ever present in the back of my mind – fearing that one day I will be unveiled for the world to see. As an immigrant, first-generation-to-college Black woman whose lifestyle, education and career aspirations led to me being a minority in many spaces, I was often told that to achieve the same level of success and respect as a non-minority peer, I had to be an overachiever. That everything that I do will be scrutinized, my work will always be double-checked for accuracy and people like me are rarely given second chances. This advice motivated me in my earlier years, but it has now become a major contributor to my imposter syndrome.

How has imposter syndrome manifested itself in you?

A large part of life is learning and growing from your mistakes, and it’s in challenging times – such as residency – that imposter syndrome rears its ugly head. In some ways, imposter syndrome has acted as a source of motivation to do better and be better throughout residency, but many times it has made me feel as though I somehow made it to where I am because of a fluke in the system – and it’s in moments of making a mistake or not knowing how to manage a complex patient that these feelings of inadequacy often take over.

How did you handle these feelings – and how did you move beyond them?

It can be particularly challenging, but I’ve found that vocalizing these feelings

to others in residency helps me to move beyond them. In particular, sharing these feelings in moments when they are heightened forces me to recognize that this overwhelming self-doubt as it relates to my skills and knowledge are internally derived, and not necessarily shared by those I work with.

What advice do you have for residents who experience imposter syndrome?

The first step is to acknowledge that these feelings of inadequacy and selfdoubt stem from imposter syndrome and they are more common than you might think. Although it requires making yourself vulnerable, talk to co-residents and attendings who you trust about this. They may have experienced very similar feelings at some point, as well.

Secondly, I think we all need to give ourselves some grace and often need reminders that residency is a learning process. If you already possessed all the knowledge and skills required to be a plastic surgeon, there wouldn’t be a need for residency. Even the best of us make mistakes. The goal is to learn from your own and others, so as not to repeat them.

Finally, try to celebrate your wins and successes as much as you dwell on your mistakes. They serve as a reminder that being a resident physician and budding surgeon did not happen to you because of some fluke in the system. You earned your place and worked just as hard – if not harder – as others to be in this position. You deserve to be here.

Ryan Badiee, MD PGY-3, University of Washington, Seattle

How do you define imposter syndrome?

Imposter syndrome is a clandestine feeling of inadequacy that often takes root in situations where we err or are uncertain – in spite of a past record of competence. Even when accomplishing complex and technically difficult feats, one small mistake can engender internalized selfdoubt, that our prior achievements can be attributed to luck and that we didn’t deserve the opportunities afforded us.

How has imposter syndrome manifested itself in you?

Imposter syndrome has manifested when my surrounding circumstances trigger pre-existing insecurities or preoccupations. For example, I expect myself to become more knowledgeable and independent over the course of each rotation with repeated exposure to the same problems and protocols. However, the disorientation associated with transitioning to a new service every month – and across a broad array of specialties – rendered it impossible to constantly uphold this high standard of competence.

The resulting feeling – that I’m less capable than I had thought and that my self-confidence was misguided – is a common manifestation of my imposter syndrome. Perfectionism, which is arguably a necessary precursor to matching into a competitive field such as plastic surgery, also made me vulnerable to imposter syndrome. As an intern, I still harbor some residual stress from my experiences as a medical student, when I overprepared for any interaction with my seniors and attendings to avoid be-

continued on page 34

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 7

WHAT I KNOW NOW THAT I WISH I KNEW THEN

PSR: WHAT DO YOU ENJOY MOST ABOUT BEING A PLASTIC SURGEON?

Dr. Neumeister: Plastic surgery is an incredible specialty. I enjoy the diversity and complexity, as well as the challenges that force us to create new techniques and innovate regularly.

PSR: WHAT DO YOU ENJOY LEAST ABOUT BEING A PLASTIC SURGEON?

Michael Neumeister, MD, is chair of the Department of Surgery and chief of the Division of Plastic Surgery at Southern Illinois University – as well as J. Roland Folse, MD, Endowed Chair; Elvin G. Zook Endowed Chair; and Plastic Surgery Residency Program director.

Dr. Neumeister is also vicepresident of the American Association of Hand Surgery and editor of its journal, HAND. Past president of The PSF and the American Society of Reconstructive Microsurgery, Dr. Neumeister completed general surgery residency at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada, and plastic surgery residency at Manitoba University in Manitoba, Canada. His fellowship training includes hand and microsurgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and microsurgery at Southern Illinois University.

Dr. Neumeister: I wish the average layperson would understand how diverse and comprehensive the field of plastic surgery is.

PSR: WHAT IS THE HARDEST YEAR OF TRAINING?

Dr. Neumeister: It’s often the internship year, as one needs to learn surgical techniques, patient care and being a professional – with every rotation being new and, at times, overwhelming.

PSR: WHAT QUALITIES MAKE A GOOD INTERN, JUNIOR RESIDENT AND SENIOR RESIDENT?

Dr. Neumeister: Many of the qualities of a good intern are similar to those of a good junior or senior resident. In fact, the same qualities also can be said of defining good faculty: Honesty, integrity, self-directed, enthusiastic, creative, team player, respectful, eager to learn, empathetic and hard-working. Everyone should read as much as possible. Being inquisitive is also very important.

As an intern, one should seek more information on the principles of surgical care, as well as the basics on the principles of plastic surgery. Interns should practice knot-tying constantly. The proper handling of instruments and various tissues should be practiced repetitively.

The junior resident should try to acquire dexterity techniques and broaden their understanding of 3-D reconstruction and aesthetic principles.

The senior resident should develop the leadership skills that will help them in their practice, and be very observant of attending techniques and decisionmaking. Teaching junior residents helps the seniors better understand areas of complexity and the efficiency of various procedures.

PSR: IF YOU COULD REPEAT RESIDENCY KNOWING WHAT YOU KNOW NOW, WHAT WOULD YOU DO DIFFERENTLY?

Dr. Neumeister: I would try to reduce surgeries to specific soundbites throughout the case. I would then pick a specific point in every surgery to master, until I had a greater level of competence for the entire operation. I would ask my attending to work like a coach to optimize each step in an operation. Many coaches tell their players that they need to work on specific tasks on any one day, breaking-down the skills to certain parts of a game. Surgery can be done the same way to make the resident better and more efficient. I would have mentors and coaches that I would lean on throughout my training.

8 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Winter 2023

Interviewed by Alexis Ruffolo, MD

PSR: WHAT’S YOUR ADVICE FOR RESIDENTS INTERESTED IN GOING INTO ACADEMIC MEDICINE?

Dr. Neumeister: I’m thrilled when residents want to go into academics. It warms my heart. It would be unreasonable, though, to believe that all residents would or should go into academics, as we need our graduates in communities outside of academics to service in a thorough, competent and passionate manner. If you’re seeking academics, a post-graduate fellowship helps bring some added expertise to your new position. Always seek the fellowship that excites you – and work hard to learn as much as you can from your new attendings. It’s your year to shine. As fellowships are competitive, increasing your research and teaching portfolio may be important. The earlier one decides on entering academics, the more robust your academic portfolio will become.

PSR: HOW DID YOU MAKE THE MOST OF YOUR FELLOWSHIP YEAR – AND WHAT IS YOUR ADVICE FOR THOSE CURRENTLY IN THEIR FELLOWSHIP?

Dr. Neumeister: Fellowship year is a short period in your life when you should be trying to push yourself to acquire as much new knowledge and surgical skill as you can. You have chosen to spend extra time to become more specialized, and you should make the most of that year. Be extremely inquisitive and never shy away from the difficult cases. Be a sponge!

PSR: WHAT SKILL HAVE YOU LEARNED THAT YOU WISH YOU HAD EARLIER IN YOUR CAREER?

Dr. Neumeister: Time management. Understanding how to be involved in various committees, societies and boards and still be productive in the academic, clinical and teaching arenas in which we reside takes some time to become efficient without incurring stress or the feeling of being overwhelmed.

PSR: HOW DO YOU BECOME A GOOD TEACHER IN THE O.R.?

Dr. Neumeister: Becoming a good teacher in the O.R. can be difficult. We all assume we’re good, but as surgical educators we need to adjust our style or teaching techniques to the various levels of learners we have in the room at any one time. Sometimes there are different levels of learners in the same case, so the discussions need to change based on such levels. Asking open-ended questions such as “What if….” helps the resident work through specific situations. Surgical educators should learn to become good coaches so they can help residents get through focused, goal-oriented tasks. This means breaking the surgery into specific

components and then taking a deep dive into these tasks. Focus on one or two items to master during the surgery. Trying to ask the resident to become a master surgeon all in one setting is a losing battle. No one asked Wayne Gretzky or me to master hockey all at once – coaching was needed. Most important of all is patience. A good teacher must have patience.

PSR: WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE CASE TO PERFORM?

Dr. Neumeister: My favorite case is a toeto-hand surgery – highly technical and highly rewarding. It restores form and function, and it is awesome. |

Dr. Ruffolo is PGY-4 at Southern Illinois University.

Dr. Ruffolo is PGY-4 at Southern Illinois University.

HISTORY

Temple Plastic Surgery

By Carl Manstein, MD; David Kim, MD; & Ope Asanbe, MD

Earl Browne, MD, created an intense hand-surgery program while hand surgeon Amitabha Mitra, MD, took the reins at Temple, and Chris Tzarnas, MD, helped Temple become a more-academic program with his 2008 ascension to department chief. After Dr. Tzarnas’s passing, the division was led by James Bradley, MD; Aron Wahrman, MD; James Fox, MD; and today by Sameer Patel, MD, who brings a fresh perspective with his expertise in microvascular surgery and free-tissue transfer. Full-time Temple University faculty consists of four academic and diverse plastic surgeons, all of whom contribute considerably to the education of their residents.

The plastic surgery history tied to Temple University in Philadelphia is rich and storied.

The Lewis Katz School of Medicine Chairman William Babcock, MD, was known for his eponymous surgical clamp and sump drain, use of stainless-steel wire sutures – and for being a pioneer working in spinal anesthesia, cranioplasty, osteogenic sarcoma, intestinal cancer (abdominoperineal proctosigmoidectomy), hernia repair and osteomyelitis. John Kolmer, MD, was a pioneer in community health, and the serologic test for syphilis bearing his name is still used extensively in laboratories around the world. W. Emory Burnett, MD, performed the first human pneumonectomy in Philadelphia in 1938. Neurophysiologist and neurosurgeon Ernest Spiegel, MD, and Henry Wycis, MD, collaborated to found stereotactic surgery at a time when prefrontal lobotomy was the gold standard for managing functional diseases and intractable pain. Other Temple pioneers include John Franklin Huber, MD, PhD, and Chevalier Jackson, MD, who detailed the bronchopulmonary system. Sol Sherry, MD, a pioneer in thrombosis, revolutionized the treatment of acute myocardial infarction through his work in thrombolytic therapy.

The Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, also known as the “green bible,” was written by Waldo Nelson, MD. Temple pathologist Wallace Clark, MD, is famous for his classification of the depth of melanoma. Review of Biochemistry, the text by Dawn Marks, PhD, which became the basis for a USMLE biochemistry review book universally referenced by medical students preparing for boards. Recent plastic surgery residents should recognize the name DiGeorge Syndrome, MD, who for many years was a professor of pediatrics at Temple University.

Lester Cramer, MD, DDS, still alive at age 96, was instrumental in establishing Temple’s plastic surgery residency program in the 1960s. Norris Culf Jr., MD, started the Cleft Lip and Palate Program at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, where Stuart Hulnick, MD, developed a pediatric burn care program.

PROGRAM LEADERSHIP

Sameer Patel, MD, Chief of the Division of Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery at Temple University Hospital/Lewis Katz School of Medicine and at Fox Chase Cancer Center; Associate Professor, Department of Surgical Oncology; Program Director, Plastic Surgery Fellowship Program

Christine Jones, MD, Assistant Professor of Surgery at Temple/ Katz

Xi Lin Jing, MD, Associate Professor of Surgery and Associate Program Director, Plastic Surgery Fellowship Program at Temple/Katz

Alireza Hamidian Jahromi, MD, Assistant Professor of Surgery at Temple/Katz; LGBTQ-Centered Health, Trans/Non-Binary Health, Gender-Affirming Surgery Care Team

Adam Walchak, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgical Oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center

Charles Long, MD, Chief of the Division of Plastic Surgery at Jefferson Abington Health System; Clinical Assistant Professor of Surgery at Thomas Jefferson University

Carl Manstein, MD, Temple University Hospital-affiliated private practice plastic surgeon

CLINICAL EXPERIENCE

Rotations through six hospitals: Temple University Hospital: Temple is a 721-bed tertiary and quaternary-care teaching facility respected nationally for excellence in clinical care. Considered home base, this site treats high acuity patients and provides the majority of our complex maxillofacial trauma, lower extremity and trunk reconstructions, as well as complex wounds. Additionally, Temple University Hospital is a

10 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Winter 2023

Carl Manstein , MD David Kim, MD Ope Aanbe, MD

LGBTQ Healthcare Equality Leader designated by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation (HRC) and offers comprehensive, gender-affirming care.

Fox Chase Cancer Center: A National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center research facility and hospital located in Philadelphia. The hospital boasts a rich research history with many notable research advances, discoveries and awards – including the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1976 for the discovery of Hepatitis B and the Hepatitis B vaccine and the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation.

Jefferson Abington Hospital: The flagship hospital of Jefferson Health-Abington (part of Jefferson Health), located in the northern suburbs of Philadelphia, is an 800-bed community-based hospital, as well as a regional referral center and teaching hospital that provides residents the opportunity to participate in the treatment of breast reconstruction, maxillofacial trauma and complex wounds.

Philadelphia Hand to Shoulder Center: One of the oldest and most prestigious orthopedic and plastic surgery hand surgery practices in the country, with internationally renowned surgeons and therapists. During this rotation, residents participate in the comprehensive treatment of disorders and injuries to the hand, wrist, elbow and shoulder. The residents also work alongside the internationally renowned team of the Limb Restoration Clinic at the Philadelphia Hand to Shoulder Center, treating complex conditions that limit limb function resulting from congenital disorders, disease or traumatic injuries.

Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center: Located in Hershey, Pa., this facility is one of the nation’s premier university health centers. Penn State Health Children’s Hospital is the region’s only children’s hospital and its specialties have been ranked by U.S. News & World Report every year for the last 12 years. Lancaster Cleft Palate Clinic is the oldest clinic in the world devoted to the comprehensive care of children born with cleft lips and palates and other craniofacial anomalies.

St. Luke’s University Health Network: A regional, nationally recognized network providing services at 12 hospital sites, headquartered in Bethlehem, in the Lehigh Valley region of eastern Pennsylvania. Residents participate in the wide breadth of plastic surgery during rotation with

this hospital system, including reconstructive surgery of the head and neck; breast; trunk; lower extremity; complex wounds; and cosmetic surgery.

EDUCATIONAL CURRICULUM

The Temple University Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery program has an organized, weekly didactic curriculum. Lectures are held by esteemed faculty and visiting professors. A core component of these weekly didactics are Fellow-run educational lectures. Our program follows the ASPS learning objectives to better-prepare for the annual In-Service Exams, as well as the ABPS qualifying and certifying exams. At Temple, multiple simulation labs are provided throughout the academic year that range from casting to cadaver dissection and saw-bone labs. There are also quarterly injection clinics where Fellows practice the latest techniques of filler and neurotoxin injections, as well as multiple journal clubs throughout the academic year during which the latest plastic surgery literature topics are discussed with the faculty.

RESIDENT BENEFITS

One of the strengths of Temple’s independent plastic surgery program is its ability to rotate at six sites across multiple hospital systems and community settings. Residents rotate through Temple University Hospital; Fox Chase Cancer Center; Jefferson Abington Hospital; Philadelphia Hand to Shoulder Center; St. Luke’s University Health Network; Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center; and numerous private practice settings.

PGY-6 residents gain early exposure to microsurgery and spend three months at Fox Chase. They also rotate for two months at Philadelphia Hand to Shoulder, St. Luke’s Hospitals, Penn State Hershey for craniofacial and pediatric plastic surgery, and one month at Abington Memorial. PGY-7 residents undergo twomonth rotations at all six core rotation sites. PGY-8 residents serve as administrative chief residents and focus on aesthetics with a three-month block at Jefferson Abington Hospital. This includes the affiliated Abington center and various private practice settings.

Throughout the academic year, residents participate in journal clubs hosted at venues throughout Philadelphia. They also coordinate and participate in injectable clinics and cadaver labs at Temple University Hospital. Residents hold social events including multiple social departmental and divisional parties throughout the year; formal graduation ceremony at The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (Mutter Museum); and a plastic surgery graduation dinner at Dr. Patel’s home. Residents have access to free mental wellness, guided workouts, and convenient telemedicine and meditation apps through Temple University Hospital. |

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 11

Cadaver Flap Clinic with with Sameer Patel, MD (left); David Kim, MD; and Adam Strohl, MD

Q&A WITH CHRISTINE M. JONES, MD

In this installment of Faculty Focus, we present ASPS member Christine M. Jones, MD, assistant professor of Surgery in the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Temple University Hospital and Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Philadelphia.

Dr. Jones earned her medical degree at Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, and completed a plastic surgery residency at Penn State Hershey Medical Center and a Fellowship in Craniofacial and Pediatric Plastic Surgery at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Dr. Jones’ clinical interests include pediatric plastic surgery, breast reconstruction, lower-extremity reconstruction/limb salvage, aesthetic surgery and noninvasive rejuvenation. Among other accolades, she’s been awarded the Stryker Fellowship by Operation Smile and the Stephen H. Miller Resident Teaching Award by Penn State College of Medicine.

PSR: HOW DID YOU PREPARE FOR A COMPETITIVE FELLOWSHIP?

Dr. Jones: Being a good resident prepares you to match into fellowship. Paying attention to detail, caring well for patients, finishing what you started and being the one to go the extra mile will stand out to your faculty and peers in any setting. When it comes time to match into fellowship and apply for jobs, the recommendations from those who know you go farther than almost anything else.

PSR: WHAT IMPACT DID THE FELLOWSHIP HAVE ON YOUR CAREER?

Dr. Jones: Fellowship provided the foundation for advancing as a craniofacial surgeon. In my fellowship, we did all types of craniofacial and pediatric plastic surgery – cleft, craniosynostosis, orthognathic, microtia and microsurgery. This breadth of training provided me with a wide skillset that served me well in the job search and into my current practice.

PSR: HOW IMPORTANT IS A MENTOR – AND HOW CAN WE FIND ONE?

Dr. Jones: Finding a mentor you trust and with whom you relate well is one of the most important things a resident can do during training. Ideally, this will be someone with whom you can identify on a personal as well as a professional level. Good mentors are lifelong colleagues; you will find yourself reaching out to your mentor for advice well into your career. Most residents are assigned a mentor early in training. This is a helpful start, but you should also assess your own goals, needs and personal attributes, and compare them with what you see each of your faculty members modeling. Look for someone with whom you relate on as many levels as possible. In some cases, having more than one mentor can be beneficial – especially if they can each lead you in a specific area.

PSR: WHAT’S THE MOST IMPORTANT QUALITY IN A RESIDENT?

Dr. Jones: Integrity. Integrity is doing the right thing when no one else is watching. Make good decisions with the little things, and the big things will take care of themselves. No one is perfect, and it takes integrity to admit when you’ve made a mistake or you don’t know the answer. Integrity leads to trust – and trust builds teams and relationships.

PSR: HOW DO YOU BALANCE YOUR PROFESSIONAL AND PERSONAL LIVES?

Dr. Jones: An honest and accurate understanding of yourself is the basis of achieving balance. What is it that only you can truly do? Prioritize these things. For my daughter, I’m the only one who can be mom. It’s important for me to be there for quality time and her special moments. What you chose to do, do it well. Be present in each commitment you accept; this means avoiding overscheduling yourself. Make time for self-care – read a book, go for a walk, go to the gym. I like to get up early in the morning to read, then start my day from a refreshed perspective.

12 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Winter 2023

PSR: WHAT WAS YOUR GREATEST NON-MEDICAL CHALLENGE OF TRAINING?

Dr. Jones: I had a family member who was ill during the first several years of residency. When he was hospitalized, I would go to visit him post-call. Our family lived about an hour-anda-half away during residency, so having them relatively close was a source of strength.

PSR: WHAT ARE SOME OF THE CHALLENGES YOU ENCOUNTER ON A REGULAR BASIS?

Dr. Jones: Challenges fall into strategic versus mundane categories. The mundane are the ones with which residents are most familiar – O.R. turnover, having the right equipment for the case or managing the nonadherent patient. It’s important not to get too weighed-down with this, though. Focusing on the strategic challenges – where do you want your career to go, what are areas of potential growth, what opportunities are around the corner – keeps your career fresh and your perspective marketable.

PSR: WHAT ADVICE DO YOU HAVE FOR PLASTIC SURGERY RESIDENTS?

Dr. Jones: Try to soak up every experience like a sponge. You naturally focus on operative detail, which is important. Look for other opportunities, as well. Go to clinic; learn what operation to do and when; learn what a normal, postoperative course looks like. Compare how your attendings do things. Look at how your mentors build professional relationships and build programmatic systems. These are the things you may miss if you aren’t paying attention in residency.

PSR: COMPLETE THIS SENTENCE: “I KNEW I WANTED TO BECOME A PLASTIC SURGEON WHEN…”

Dr. Jones: I saw the many ways we can restore hope in people’s lives. We have opportunities to interact with people at critical moments and turn their lives to the better. |

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 13

Welcome to the Independent Plastic Surgery Residency at the Temple University Hospital/ Lewis Katz School of Medicine. I’m program director of the training program and chief of plastic surgery at Temple University Hospital/Lewis Katz School of Medicine and Fox Chase Cancer Center. At first “peek,” you might not recognize the training program, which has made significant changes over the past five years and continues to gain recognition for its comprehensive and high-quality training.

We’ve expanded our training program to include rotations at centers of excellence throughout the region to collectively provide a comprehensive experience for our trainees. In addition to the main sites at Temple University Hospital and Fox Chase Cancer Center, we’re fortunate to have the following sites as our partners in training:

• Philadelphia Hand to Shoulder Center

• Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center

• Jefferson Abington Hospital

• St. Luke’s University Health Network

Each of these sites provides general plastic and reconstructive experience, as well as areas of specialization. At Temple University Hospital, Fellows receive extensive exposure to craniofacial trauma, lower-extremity trauma, complex reconstruction, general plastic surgery and robust experience in gender-affirmation surgery. At Fox Chase Cancer Center, they gain exposure to a wide variety of complex reconstructive cases in the oncologic setting – including complex microsurgical reconstruction of the breast, head and neck, and lower extremity. Additionally, Fellows are exposed to surgical options in the treatment of lymphedema. Philadelphia Hand to Shoulder Center provides a unique opportunity to work with internationally recognized faculty and treat a wide range of disorders affecting the upper extremity. Included in this rotation is exposure to replantation. At Penn State Hershey, they spend time with internationally recognized faculty in the field of pediatric craniofacial surgery. St.

Director, Sameer Patel, MD

Luke’s and Abington round-out rotations with a focus on aesthetic surgery of the face and trunk, as well as complex reconstruction and general plastic surgery.

These various rotations not only provide a breath of clinical exposure, they also provide experience with nationally and internationally recognized faculty in the various disciplines of the specialty.

It’s with great pride that we developed this program to what it is today. Acknowledgment of our core faculty – including Christine Jones, MD; Adam Walchak, MD; Lin Jing, MD; Alireza Hamidian, MD; Carl Manstein, MD; and Charles Long, MD – is truly deserved, given their significant contributions to enriching the program.

In addition to the clinical strength of the program, we offer the opportunity to participate in meaningful research projects. All the sites provide opportunities for developing interesting projects to advance the field of plastic surgery. Both Temple University Hospital and Fox Chase Cancer Center have dedicated research groups that meet regularly to see projects through to their conclusion. In addition, Fox Chase Cancer Center has a dedicated research Fellow who helps coordinate all research projects being conducted at the site. Over the past three years, we’ve seen a rapid and sharp rise in the number of national presentations as well as publications– and we’re confident this trend will continue well into the future.

It’s my opinion that one of the true strengths of any program is its social interactions and camaraderie between the Fellows, faculty and staff. In this day and age of increasing expectations of healthcare providers, the need for a supportive environment in a training program is imperative

A Message From the

Program

14 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Winter 2023

Sameer Patel, MD

Program Director, Sameer Patel, MD

to its success. We have numerous social gatherings throughout the year, including journal clubs, a holiday party, a graduation party and happy hours, during which we have the opportunity to get to know each other and to stay engaged in the important events in everyone’s lives outside of plastic surgery. We value diversity of culture and beliefs, and this is evident in the diversity of our faculty and trainees.

As we look to the future, we recognize the trend in plastic surgery training has moved toward an integrated model, and this is something we are considering. We see the merits of both an independent and integrated program. We also recognize that as plastic surgery continues to innovate and

develop new fields within our specialty, we will need to remain nimble to make sure that our Fellows continue to get the best education and experience possible. Although change might not always be easy, it’s sometimes necessary. We continue to recruit well-trained faculty that can bring through their skill sets even more diversity to our program.

I hope this overview gives readers a glimpse into what we’ve accomplished and what the future holds for the Temple University Hospital/Lewis Katz School of Medicine training program. We’re proud to have trained numerous plastic surgeons – many of whom have gone on to complete highly competitive fellowships, while others have directly entered successful practices. |

Residents: Submit Your Abstracts for #PSTM23

Submission Deadline: April 28

Authors of the 50 top-rated resident abstracts will be invited to present live podium presentations in dedicated sessions at #PSTM23.

Submission site opens February 21*

*Subject to change.

OCT. 26-29, 2023

A Message From

the

PlasticSurgeryTheMeeting.com/Residents

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 15

Philadelphia

By Heather Peluso, DO

By Heather Peluso, DO

With only 24 hours in Philadelphia, an abundance of activities awaits. A day in the City of Brotherly Love starts with breakfast at a family-owned Lebanese-French fusion restaurant, Cafe Au Maude. From here, travel to the Logan Square area to snap your photo in front of the Love Statue at Love Park. You’ll spot Benjamin Franklin staring down upon Broad Street from atop City Hall. Your next stop will be at the Barnes Foundation along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, where you can gaze at brilliant works by Picasso, Monet and Renoir.

Take a lunch break at Reading Terminal Market, one of the nation’s oldest and largest public markets, which hosts myriad vendors and is enjoyed by locals and tourists alike. Considering it’s the home of the famous DiNic’s Roast Pork & Beef sandwich place and several Pennsylvania Dutch restaurants, deciding which cuisine to enjoy can be one of your toughest decisions of the day.

Your last stop before dinner will be at the grounds housing the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall, which mark the birthplace of the United States. You can pose next to the cracked Liberty Bell and learn of its iconic message. Walking inside of the brick walls of Independence Hall leads you to the spot where the Declaration of Independence was signed.

Philadelphia is known for its excellent restaurants, and a strong dinner recommendation is El Vez – a contemporary Mexican restaurant with brightly colored, high-backed velvet booths and a catchy low-rider bike rotating in the center of the dining room to capture its eclectic spirit. El Vez is well-known for its original take on traditional Mexican dishes, including pistachio guacamole and shrimp tacos. Each dish pairs perfectly with their hand-squeezed lime margaritas.

Philadelphia hosts several concerts, including the Made In America Music Festival held in the city every Labor Day weekend. In addition to music, Philadelphia has several professional sports teams, including the MLB Phillies, the NFL Eagles, the NHL Flyers, the NBA 76ers and lacrosse’s Philadelphia Wings. Getting to and from games is easy, as Philadelphia’s robust public transportation system runs throughout the city – with trains that span into the suburbs and neighboring states. (New York is a short, 90-minute train ride from 30th Street Station.)

Whether impersonating Rocky by running up the famous steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art with your arms held high, perusing the exhibits at the Franklin Institute, tasting an authentic Philadelphia cheesesteak, catching a Phillies game or watching a show at The Met, Philadelphia is rich in arts, history, entertainment, sports and fine dining. The city is also the perfect complement to our plastic surgery training program. |

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 17

CONGENITAL EAR ANOMALIES

By Alexis Ruffolo, MD

Children with congenital ear anomalies are frequently subject to teasing from peers and can suffer significant psychological effects, despite the minimal physiologic morbidity of the diagnosis. This physiological condition is consistently encountered on the InService Exam, so this edition of Inservice Insights will review clinical findings and standard reconstructive approaches for commonly tested congenital ear anomalies.

EMBRYOLOGY OVERVIEW

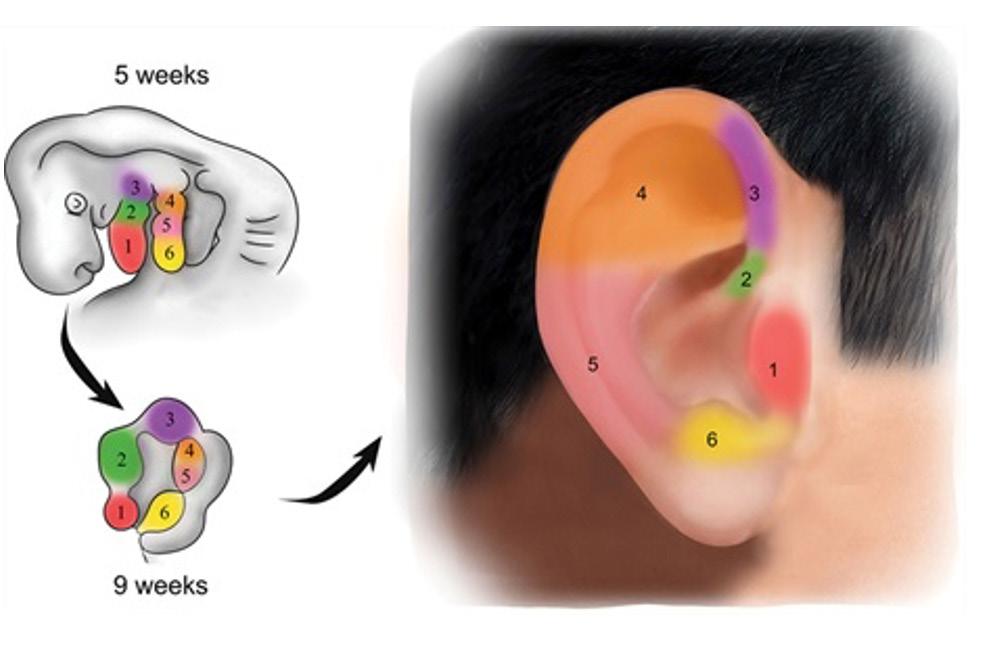

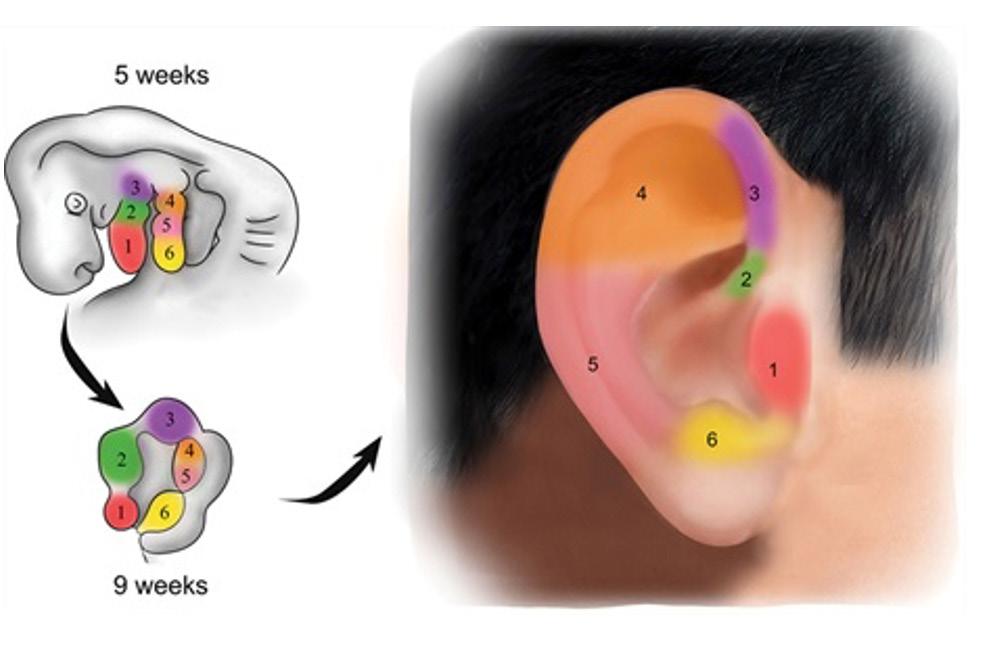

Ear development begins at the fifth week of gestation, and the fetal auricle is formed during approximately the ninth week of gestation. The external ear is formed from mesenchymal proliferation of the first and second pharyngeal arches. Six auricular hillocks fuse to form the auricle. Hillocks 1-3 arise from the first pharyngeal arch and form the tragus, root of helix and superior tragus. Hillocks 4-6 arise from the second pharyngeal arch to form the antihelix, antitragus and lobule.1

Congenital ear anomalies can be categorized as malformations or deformations. Ear malformations are characterized by missing structures or the absence of the ear. Ear deformations are characterized by ear anatomy that’s present but abnormal.

CRYPTOTIA

In cases of cryptotia, the superior ear is buried beneath temporal scalp skin. This is due to an anomaly of the intrinsic oblique and transverse auricular muscles.2 On examination, the ear can be pulled from the scalp and the auricle typically appears normal, but in some cases the cartilage is misshapen.

Reconstruction requires freeing the buried auricle and resurfacing with local tissue rearrangement or skin grafting. If misshapen, cartilage grafting may be required to augment the native cartilage framework, in addition to soft-tissue rearrangement.

PROMINENT EAR

Prominent ear is caused by a combination of the underdevelopment of the antihelical fold and excess conchal wall, with resultant widening of the conchal-mastoid angle.

Prominent ear can be treated with ear molding if initiated within the appropriate window of time to avoid the need for surgery. Surgical correction of the prominent ear involves recreation of the antihelical fold and decreasing the size of the conchal bowl.3 The most-common techniques involve cartilage molding, breaking or scoring. Techniques are often used in combination to achieve the best aesthetic result.

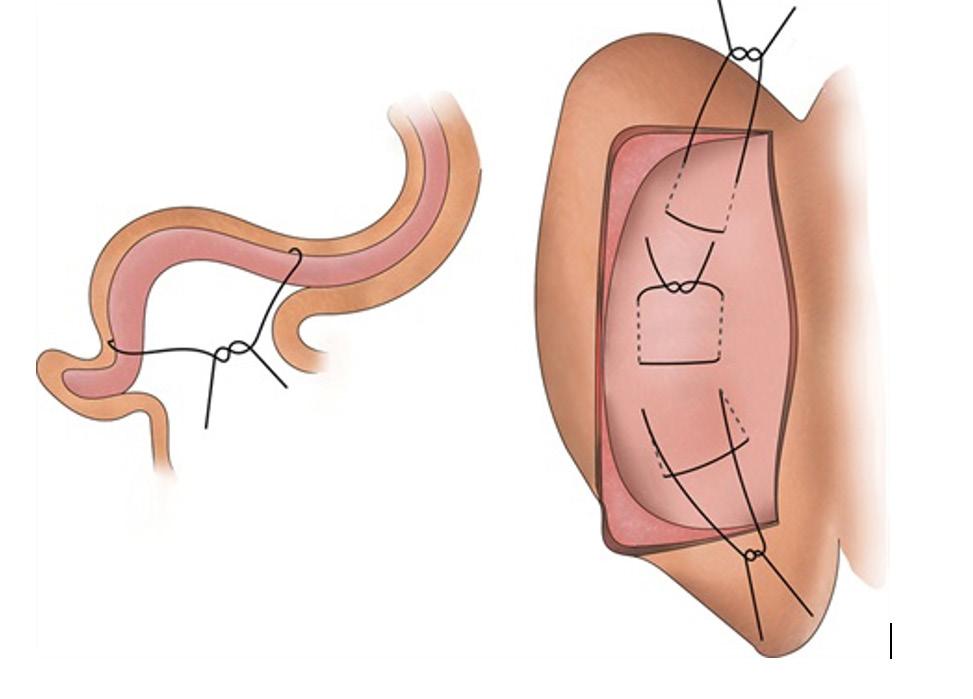

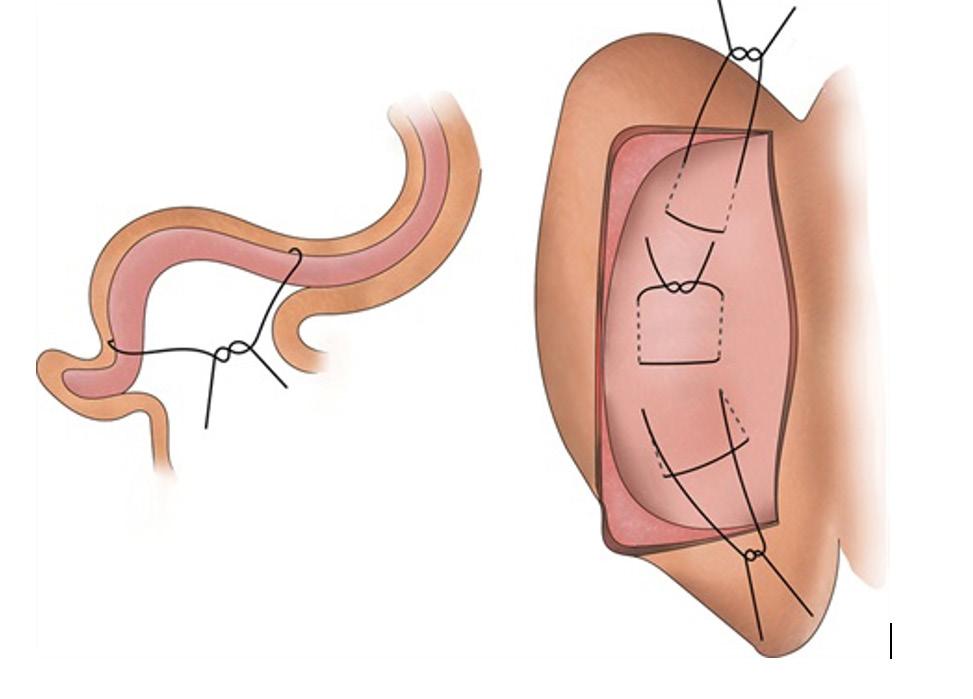

The Mustarde technique is used to correct a poorly defined antihelical fold. The shape of the desired antihelix is marked, and then mattress sutures are placed from a posterior approach. Sutures capture only the cartilage of the antihelix, and excess posterior skin is excised.

Auricle embryology diagram, used with permission from Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, August 2020: “Management of Congenital Auricular Anomalies” by Joukhadar, Nadim M.D., et. al.

18 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Winter 2023

Mustarde sutures, used with permission from Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, August 2020: “Management of Congenital Auricular Anomalies” by Joukhadar, Nadim M.D., et. al.

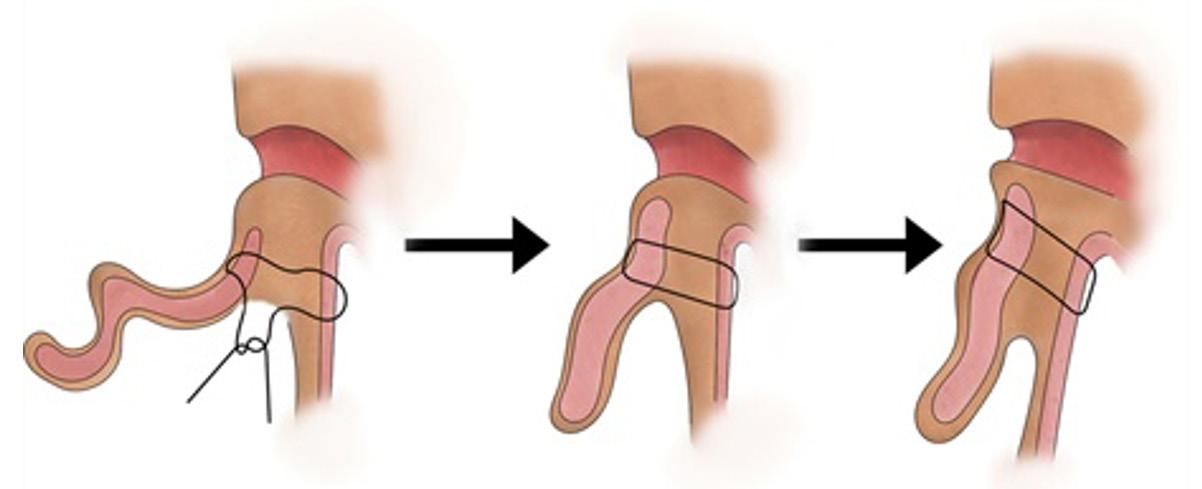

The Furnas technique is used to address conchal excess. Posterior conchal skin is excised in an ellipse. The posterior auricular musculature is exposed and can be resected if necessary. Mattress sutures capture conchal cartilage and secure it to the periosteum underlying the mastoid fascia.

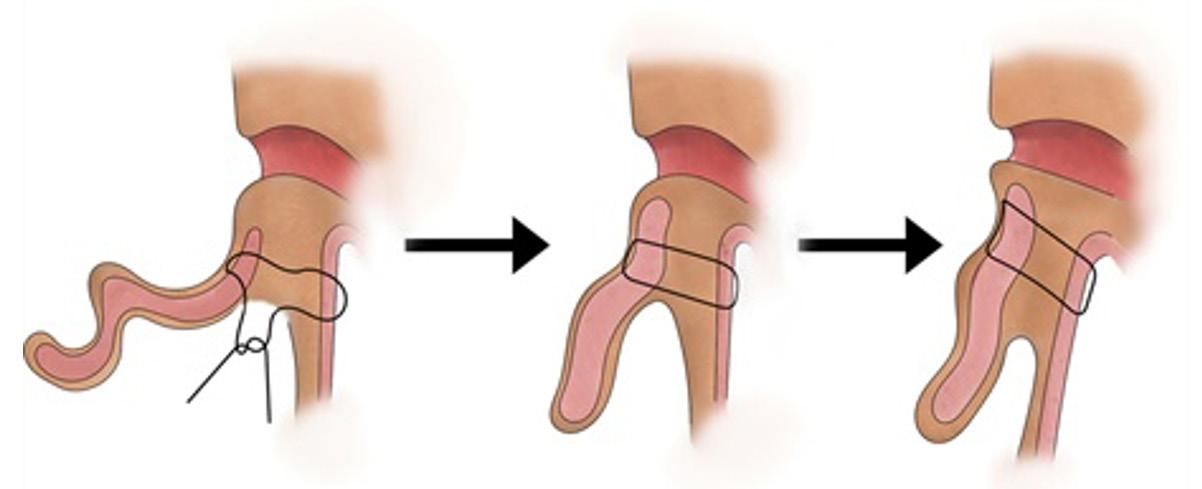

Constricted ear, used with permission from Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, October 2010: “Ear Molding in Newborn Infants with Auricular Deformities” by Byrd, H. Steve, MD, et. al.

scapha, antihelix and concha. Lop-ear deformity is a type of constricted ear, defined by deficient helix and scapha with an underdeveloped antihelix and downturned helix. If the patient presents during infancy, ear molding is the treatment of choice. Surgical reconstruction must include helix lengthening.4 The crus of the helix can be recruited into the helix, resulting in helix lengthening. Severe cases (Tanzer 3) may be treated like microtia with reconstruction using a rib cartilage framework instead of the native cartilage.

MICROTIA

Microtia is characterized by the underdevelopment or absence of the auricle. Microtia is commonly associated with middle ear and external auditory-canal defects. Patients require audiology evaluation, and most hearing deficits are managed with conductive hearing aids. Auricular malformation is a feature of many syndromes – including Goldenhar’s syndrome, Treacher Collins syndrome, oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia and Nager syndrome. The current categorization of the different types of microtia deformities were described by Nagata and Tanzer. These include anotia, lobular type, conchal type, small conchal type and atypical microtia.

CATEGORY FEATURES

Anotia Absence of any auricular structures

Lobular type

Remnant ear with lobule and helix present. Absent concha, acoustic meatus, tragus

Furnas sutures, used with permission from Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, August 2020: “Management of Congenital Auricular Anomalies” by Joukhadar, Nadim M.D., et. al.

STAHL’S EAR

Stahl’s ear is characterized by an abnormal third crus extending from the antihelix to the helix.4 Its presentation can range from mild – in which the deformity is hardly noticeable – to severe and can include an excess scapha near the abnormal crus or complete absence of the normal superior crus. Correction of the deformity requires excision of the abnormal crus, which can be performed through an incision within the helical rim to access the cartilage. If needed, the cartilage from the abnormal crus can be used to reconstruct an absent or deficient superior crus.

CONSTRICTED EAR

In cases of constricted ear, the helical circumference is shortened, drawing the auricle into a cup shape.3 Presentation is variable, classified by Tanzer into three types: involving the helix; involving the helix and scapha; and extreme cupping of the ear involving the helix,

Conchal type

Small conchal type

Atypical microtia

Remnant ear with lobule, concha, acoustic meatus and tragus present

Remnant ear with lobule, small indentation of concha

Phenotypes that do not fit into previous categories

The two most-common reconstruction options are autologous costal cartilage graft and porous polyethylene implant (MEDPOR).6 In patients who are poor candidates for autologous or implant reconstruction, a prosthetic may be used.

The Brent and Nagata techniques use autologous rib cartilage for ear framework reconstruction. The traditional Brent technique utilized four stages, compared to the two stages described in the Nagata technique. Major differences between the two methods involve the timing of lobule transposition and tragus creation. The traditional Brent technique includes separate stages for these steps, whereas the Nagata technique performs these steps during the framework implantation. The Brent technique can be performed at a younger age – around age 4-6 – compared to the Nagata technique, which is typically performed around age 10. The Nagata framework requires more cartilage; thus, the patient must be larger to provide sufficient cartilage.

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 19

34

continued on page

Facial Nerve Trauma Repair

“Consult Corner” addresses a consult commonly encountered by an on-call resident. The column begins with the reason for consult and assesses questions that might go through a resident’s mind as he or she heads to the emergency department to see the patient. Key aspects of the history and physical, as well as additional testing that should be obtained, are also presented. Finally, a review of the decision-making process will present possible management strategies, all of which are synthesized into the context of an actual case.

By Aradhana Mehta, MD

19 y/o assault with multiple stab wounds. Trauma provider concerned about 19 y/o involved in altercation w/multiple stab wounds to the face, body. Patient appears to have some unilateral facial deficits.

FACIAL NERVE ANATOMY

The facial nerve consists of intracranial, intratemporal and extracranial components. The extracranial component emerges from the stylomastoid foramen and is protected by the mastoid tip. Once the nerve exits the skull base, it can be found medial to the tympanomastoid suture, running lateral to the styloid process. The facial nerve gives off branches to the stylohyoid muscle, posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and occipitalis and auricularis muscles prior to making the journey around the earlobe.

The facial nerve enters the parotid gland preauricular, where it travels between the superficial and deep lobes of the parotid. The nerve then divides into two main branches – the temporofacial (superiorly) and cervicofacial (inferiorly), which further divide into multiple, other branches which exit the parotid and travel deep to the SMAS. Simply put, the facial nerve has five divisions with unique functions: temporal, zygomatic, buccal and marginal mandibular. However, in reality the branching patterns and interconnections are far more complex. The arborization of the facial nerve allows for distal injuries to be masked by the proximal interconnections.

20 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Winter 2023

• Temporal division: Pitanguy’s line, which is 0.5 cm inferior to the tragus to 1.5 cm superior to the lateral eyebrow.

• Zygomatic and buccal division: Anatomically very difficult to distinguish and are often considered as one unit. Zuker’s point – a landmark to identify the branch of the zygomaticobuccal branch that innervates the zygomaticus major – is the midpoint of the line drawn from the root of the helix to the oral commissure. The zygomaticus major branch is usually found within 2.3 mm of this location.

• Marginal mandibular division: Two to four branches that descend from the parotid and run below the body of the mandible, deep to the platysma. Eventually, they travel across the inferior border of the mandible and can be found superficial to the facial vessels.

• Cervical division: Generally, there’s only one cervical branch that exits the parotid anterior to the angle of the mandible and does not divide until it passes inferior to the mandibular border.

INITIAL EVALUATION

Never forget your ABCs. Initial evaluation should emphasize ruling-out any life-threatening injuries. Once the patient is deemed stable, you should begin your examination systematically. Begin the facial nerve examination by checking sensation to light touch in the V1, V2 and V3 distributions. Compare the sensitivity to the contralateral side and with the patient’s baseline.

Begin testing each branch of the facial nerve by asking the patient to perform various maneuvers. Have the patients raise their eyebrows (temporal branch), squeeze their eyes closed (zygomatic), puff their cheeks (buccal), smile (marginal mandibular) and purse the lips (cervical). Loss of lip depression can signify either a marginal mandibular or cervical branch injury. It’s important to make the distinction between the two by having the patient evert their lower lip. If lower-lip eversion is intact, this signals that the injury is limited to the cervical branch, as the mentalis function remains intact (innervated by the marginal mandibular nerve).

The patient is noted to have multiple lacerations to the face, with one deeper stab wound located approximately 1 cm anterior and inferior to the tragal pointer. He appears to have unilateral, left-sided facial asymmetry while smiling, but lower-lip eversion remains intact.

GENERAL CAUSES OF FACIAL PARALYSIS

Although this patient’s etiology is clearly trauma, bear in mind that there are several other causes of facial paralysis. Most commonly, Bell’s palsy is seen in adults and is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, as it is idiopathic in nature. The main tenets of treatment include corticosteroids (optimally started within 24 hours) and antivirals. Infection, trauma and iatrogenic injury are considered the culprit next most likely. If new onset bilateral paralysis is noted, Lyme disease is a common diagnosis.

Congenital unilateral lower-lip paralysis (CULLP) is an isolated dysfunction of a unilateral marginal mandibular nerve that’s often recognized with asymmetric crying facies and can be attributed to the use of forceps. Furthermore, syndromic etiologies are most commonly found to include hemifacial microsomia and Mobius syndrome. Those with Mobius syndrome generally have bilateral palsy of CN VI and VII.

CONCERNS

The greatest concern associated with facial nerve injuries in the upper face is ocular damage secondary to corneal exposure. Lagophthalmos results from the unopposed upward force of the levator palpebrae superioris (innervated by CN III) and prevents the patient from achieving complete closure of the eye. A concomitant decrease in blinking can be seen secondary to a disruption in the efferent branches of the facial nerve, leading to impaired tearfilm production. Over time, a paralytic ectropion may also be noted secondary to gravitational forces and increasing laxity. This phenomenon results in increased corneal exposure and lacrimal pump failure.

In the lower face, the primary issues are impaired speech, an inability to smile and inability to eat, and obstruction in airflow. Any impairment with smiling can be detrimental psychosocially and is particularly of concern in children, as it can impede their ability to integrate into society.

MANAGEMENT

Once a facial nerve deficit is suspected, the wound should be explored in an effort to tag the distal and proximal ends of the nerve. Ideally, the repair should be performed within 72 hours of injury, so that the distal end can still be stimulated. After 72 hours, the neurotransmitters are depleted and can no longer be stimulated intraoperatively. If the distal and proximal ends are located, a primary repair should be attempted first – ensuring that there’s no undue tension on the repair. If the distance between the ends is too large for a primary repair, an interposition graft (typically the sural nerve) can be utilized.

Intraoperatively, you may not be able to find the proximal end. Cross-facial nerve grafting from the corresponding branch is an option when the contralateral facial nerve is fully functioning. Ideally, cross-facial nerve grafting is performed within six to 12 months of injury. However, after 12-18 months, nerve transfer to either the hypoglossal or masseteric nerve can be used. Masseteric nerve transfers are typically preferred versus hypoglossal, as there can be associated tongue atrophy from the denervation when the complete nerve is used. Free-muscle transfer can be used for facial reanimation but is reserved for cases where the muscle isn’t viable for reinnervation.

continued on page 34

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 21

JOURNAL ARTICLES ON ALLOPLASTIC BREAST RECONSTRUCTION EVERY PLASTIC SURGERY RESIDENT SHOULD READ

1. Association of Radiation Timing with Long-Term Satisfaction and Health-Related Quality of Life in Prosthetic Breast Reconstruction

Nelson JA, Cordeiro PG, Polanco T, et al. Plast Reconstr Surg 2022;150(1):32E-41E.

This study prospectively evaluated patient-reported outcomes and complications among four cohorts of patients undergoing alloplastic breast reconstruction and radiotherapy at various timepoints. Patients were stratified into no radiation; radiation before tissue-expander placement; radiation after tissue-expander placement; or radiation after permanent implant. Radiation treatment leads to lower satisfaction with breasts and physical well-being of chest scores for three years postoperatively compared to receiving no radiation. The timing of radiation itself does not result in significant differences in patient-reported outcomes. However, patients in the post-implant radiotherapy group had the highest rates of capsular contracture.

2. Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Incidence: Determining an Accurate Risk

Nelson JA, Dabic S, Mehrara BJ, et al. Ann Sur g. 2020;272(3):403-409.

The authors analyzed 9,373 patients who underwent reconstruction with 16,065 implants over the 26-year study period. The overall incidence of BIA-ALCL was found to be 1.79 per 1,000 patients (1 in 559) with textured implants, and 1.15 per 1,000 textured implants (1 in 871), with a median time to diagnosis of 10.3 years. Through the first six years of followup, the cumulative incidence of BIA-ALCL was zero, rising to a cumulative incidence of 9.4 per 1,000 patients at 14-16 years.

By Mark Shafarenko, MD, & Sophocles Voineskos, MD, MSc

3. 2019 NCCN Consensus Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast ImplantAssociated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Clemens MW, Jacobsen ED, Horwitz SM . Aesthetic Surg J. 2019;39:S3S13.

Alloplastic reconstruction has been steadily increasing and remains the most-common form of breast reconstruction following mastectomy. This has been concomitant with increasing use of ADM and prepectoral reconstruction, as well as expanding indications for post-mastectomy radiation. With the commonality of alloplastic reconstruction and other modalities that may impact outcomes, it’s important for all residents to be aware of up-to-date evidence. This can help to better-inform patient decision-making and clinical counselling.

This paper summarizes the NCCN consensus guidelines on BIAALCL and highlights recommendations for diagnosis, work-up, management and surveillance. The most-common presentation is the development of spontaneous periprosthetic fluid collection greater than one year after insertion of a textured implant. Ultrasound or MRI is recommended to better evaluate these collections and masses. Fine-needle aspiration of the collection and biopsy of any masses is required – and samples should be sent for cytology, immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry. Once the diagnosis has been established, consultation with a multidisciplinary team is recommended. Extensive preoperative bloodwork and PET-CT imaging is recommended to guide surgical resection and demonstrate extent of disease. Complete surgical excision is necessary for the treatment of early-stage disease. Radiotherapy is suggested for patients with local residual disease, positive margins or unresectable disease with chest-wall invasion. Systemic therapy is warranted in patients with stage IIBIV disease and may include anthracycline-based chemotherapy, brentuximab vedotin, or a combination. Surveillance is recommended for two years following treatment and then as clinically indicated.

22 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Winter 2023 Journal Club; 2022 Winter

Mark Shafarenko, MD Sophocles Voineskos, MD, MSc

Prepectoral Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction: Safety Outcome Endpoints and Delineation of Risk Factors

Nealon KP, Weitzman RE, Sobti N, et al. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(5):898e-908e.

In univariate analyses, capsular contracture rates were significantly higher in the subpectoral group (8.5 vs. 1.8 percent), as were rates of revision (28.2 vs. 10.5 percent). However, there were no significant differences in outcomes between subpectoral and prepectoral breast reconstruction when adjusting for all confounding variables in the penalized logistic-regression model, such as age and radiation.

5. Prepectoral Versus Subpectoral Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Meta-Analysis

Li Y, Xu G, Yu N, Huang J, Long X. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;85(4):437447.

The overall complication rate in the prepectoral group was 17.5 percent, whereas the overall complication rate in the subpectoral group was 21.5 percent. However, subgroup analyses did not reveal these differences to be significant. Similarly, no significant differences were found with respect to skin necrosis or implant loss. The capsular contracture rate in the prepectoral group was 3.79 percent vs. 11.41 percent in the subpectoral group, and this difference was found to be significant.

6. An Algorithmic Approach to Prepectoral Direct-toImplant Breast Reconstruction: Version 2.0

Antony AK, Robinson EC. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(5):1311-1319.

In this paper, the authors aim to highlight their algorithm for prepectoral direct-to-implant (DTI) breast reconstruction and outline specific technical pearls to create a successful outcome. After completion of mastectomy, the skin-flap perfusion is assessed with a fluorescence imaging system (SPY), and prepectoral DTI is limited to a relative perfusion of 30 percent or greater. A sizer is then placed with the patient in the upright position and perfusion adequacy is assessed again. The implant is placed with a Keller funnel and the breast is cast for two to three weeks with Tegaderm and Reston foam. Optimal candidates are those who desire to be approximately the same size, with only mild to moderate degrees of ptosis. Obesity is a relative contraindication, with smoking and uncontrolled comorbidities being absolute contraindications. Implant rippling is minimized with the creation of a tight ADM pocket and high-cohesivity gel implants.

capsular contracture or revision rates at more than two years postoperatively. The average cost increase per case was $2,217 with ADM.

8. Updated Evidence of Acellular Dermal Matrix Use for Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A MetaAnalysis

Lee KT, Mun GH. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(2):600-610.

ADM use was associated with significant increases in the rates of infection, mastectomy flap necrosis and seroma. There were no differences in the rates of implant loss or total complications. There was a significant reduction in the rates of capsular contracture and implant malposition in the ADM cohort when late outcomes were analyzed. ADM use allowed for significantly greater intraoperative fill-volumes and total number of expansions, although there was no difference in the volume of final expansion or time to final expansion.

9. Impact of Radiotherapy on Complications and Patient-Reported Outcomes After Breast Reconstruction

Jagsi R, Momoh AO, Qi J, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(2):157-165.

Multivariable analysis showed that bilateral treatment and higher BMI were associated with developing complications at both Year 1 and Year 2. By two years postoperatively, radiotherapy among alloplastic reconstructions was associated with 2.64 times higher odds of complications, although comparable risk profiles were seen among radiated and non-radiated autologous reconstructions. Within the radiation subgroup, autologous reconstruction had a significantly lower rate of complications (OR 0.47). Radiotherapy led to significantly lower patient satisfaction scores among those in the alloplastic subgroup, but not in the autologous cohort.

10. Comparison of 2-Year Complication Rates Among Common Techniques for Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction

Bennett KG, Qi J, Kim HM, Hamill JB, Pusic AL, Wilkins EG. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(10):901-908.

7. Total Muscle Coverage Versus AlloDerm

Human Dermal Matrix for Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction

Ivey JS, Abdollahi H, Herrera FA, Chang EI. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(1):1-6.

Alloderm allowed for significant increases in initial fill volumes and fewer overall expansions. However, there was no difference in the time from expander insertion to insertion of the final implant, and no difference in time to drain removal. The total, overall complication rate was significantly higher in the ADM group (20.5 vs 8.8 percent), as was the rate of major complications (13.7 vs 5.1 percent). There were no differences in the rates of

The authors aimed to quantify complication rates among various alloplastic and autologous methods of breast reconstruction following mastectomy. Among all study patients, 32.9 percent experienced a complication. The overall complication rate was highest among patients with SIEA flaps at 73.9 percent. Patients undergoing DTI or EI procedures had the highest failure rates, at 7.1 percent each. Autologous reconstruction was associated with significantly higher odds of any complication, as well as reoperative complications. Higher BMI, bilateral reconstruction, smoking, radiation and chemotherapy were associated with higher rates of any complications and reoperative complications. Higher BMI and smoking also were associated with an increased risk of infections. Overall, autologous reconstruction had higher rates of complications but a lower risk of failure. |

4.

Plastic Surgery Resident | Winter 2023 23

Dr. Shafarenko is PGY-4; and Dr. Voineskos is an associate professor; in the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the University of Toronto.

HAND SURGERY

Plastic Surgery Perspectives” is a recurring series of posts on the PRS Resident Chronicles blog led by Stav Brown, MD, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Research Fellow in the Department of Surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. In this installment from the series featuring leaders in hand surgery, Dr. Brown interviews The PSF past President Nicholas Vedder, MD. – Rod J. Rohrich, MD, immediate-past Editor-in-Chief, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

Interview by Stav Brown, MD Research Fellow Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Nicholas Vedder, MD Chief of Plastic Surgery, vice chair of the Department of Surgery and Jamie A. Hunter Professorship in Reconstructive Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle; past chairman of the Plastic Surgery Research Council.

PSR: HOW HAS HAND SURGERY CHANGED SINCE YOU STARTED?

Dr. Vedder: There have been many major advances in hand surgery since I started 30 years ago. Certainly, new implants such as volar locking plates and the dorsal spanning plate revolutionized our treatment of complex, intra-articular distal radius fractures – eliminating external fixators and improving both short- and long-term outcomes. Clostridium collagenase revolutionized the treatment of Dupuytren contracture, nearly eliminating open surgery. Endoscopic and arthroscopic techniques for both nerve releases and joint surgery minimized the morbidity of treatment and improved outcomes. The novel concept of nerve transfers in lieu of or to augment tendon transfers in nerve palsies is exciting and advancing every year. The development of targeted muscle reinnervation and regenerative peripheral-nerve interfaces have great potential to improve upper-extremity robotics, and hand/arm transplantation has great potential, as well.

PSR: WHAT ARE YOUR MAIN INTERESTS WITHIN THE FIELD OF HAND?

Dr. Vedder: My main interests in hand surgery involve complex trauma reconstruction.

PSR: WHY DID YOU CHOOSE PLASTIC SURGERY – AND HAND SURGERY IN PARTICULAR?