Foundation and your future

» Will you

accept the challenge?

Treating the patient with a traumatic left-flank wound page 10 » The

Q&A with The PSF President Bernard T. Lee, MD, MBA, MPH page 20 From the publishers of Plastic Surgery News IN THIS ISSUE » Harvard Mass General Brigham Plastic Surgery: Heavyweights and history p. 12 » InService Insight: The copious attention to liposuction p. 22 » Microsurgery, Part V: Joseph Dayan, MD, illuminates his path p. 28 From the publishers of Plastic Surgery News ISSUE 28 | FALL 2022

INDICATIONS

ALLODERM SELECT™ Regenerative Tissue Matrix (ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM refers to both ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM and ALLODERM SELECT RESTORE™ RTM products) is intended to be used for repair or replacement of damaged or inadequate integumental tissue or for other homologous uses of human integument. This product is intended for single patient one-time use only. ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM is not indicated for use as a dural substitute or intended for use in veterinary applications.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

CONTRAINDICATIONS

ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM should not be used in patients with a known sensitivity to any of the antibiotics listed on the package and/or Polysorbate 20.

WARNINGS

Processing of the tissue, laboratory testing, and careful donor screening minimize the risk of the donor tissue transmitting disease to the recipient patient. As with any processed donor tissue, ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM is not guaranteed to be free of all pathogens. No long-term studies have been conducted to evaluate the carcinogenic or mutagenic potential or reproductive impact of the clinical application of ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM.

DO NOT re-sterilize ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM. DO NOT reuse once the tissue graft has been removed from the packaging and/or is in contact with a patient. Discard all open and unused portions of the product in accordance with standard medical practice and institutional protocols for disposal of human tissue. Once a package or container seal has been compromised, the tissue shall be either transplanted, if appropriate, or otherwise discarded. DO NOT use if the foil pouch is opened or damaged. DO NOT use if the seal is broken or compromised. DO NOT use if the temperature monitoring device does not display “OK.” DO NOT use after the expiration date noted on the label. Transfer ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM from the foil pouch aseptically. DO NOT place the foil pouch in the sterile field.

PRECAUTIONS

Poor general medical condition or any pathology that would limit the blood supply and compromise healing should be considered when selecting patients for implanting

ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM as such conditions may compromise successful clinical outcome. Whenever clinical circumstances require implantation in a site that is contaminated or infected, appropriate local and/or systemic anti-infective measures should be taken.

ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM has a distinct basement membrane (upper) and dermal surface (lower). When applied as an implant, it is recommended that the dermal side be placed against the most vascular tissue. Soak the tissue for a minimum of 2 minutes using a sterile basin and room temperature sterile saline or room temperature sterile lactated Ringer’s solution to cover the tissue. If any hair is visible, remove using aseptic technique before implantation.

ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM should be hydrated and moist when the package is opened. DO NOT use if this product is dry. Use of this product is limited to specific health professionals (e.g., physicians, dentists, and/or podiatrists). Certain considerations should be made to reduce the risk of adverse events when performing surgical procedures using a tissue graft. Please see the Instructions for Use (IFU) for more information on patient/product selection and surgical procedures involving tissue implantation before using ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM.

ADVERSE EVENTS

The most commonly reported adverse events associated with the implant of a tissue graft include, but are not limited to the following: wound or systemic infection; seroma; dehiscence; hypersensitive, allergic or other immune response; and sloughing or failure of the graft.

ALLODERM SELECT™ RTM is available by prescription only.

For more information, please see the Instructions for Use (IFU) for ALLODERM SELECT

To

available at www.allergan.com/AlloDermIFU or call 1.800.678.1605.

please call Allergan at 1.800.433.8871.

™ RTM

report an adverse reaction,

*Based on data as of October 2021. © 2022 AbbVie. All rights reserved. ALLODERM and its design are trademarks of LifeCell Corporation, an AbbVie company. ALS156812-v2 09/22 To learn more, visit www.AlloDerm.com Follow @AlloDermHCP References: 1. Data on file, Allergan Aesthetics, October 2021. 2. Data on file, Allergan, 2022; Sales Data. 3. Wainwright DJ. Use of an acellular allograft dermal matrix (AlloDerm) in the management of full-thickness burns. Burns. 1995;21(4):243-248. 4. Data on file, Allergan Aesthetics; Search Performed on PubMed in July 2022. 5. Data on file, Allergan Aesthetics, June 2022; Plastic Surgery Aesthetic Monthly Tracker. With no documented disease transmissions in 3 million implantations for more than 25 years, know that your patients will receive the proven sterility, safety, and quality you expect from AlloDerm™ RTM—the industry leader.1-5 Choose AlloDerm™ RTM for your patients. Trust. It’s what AlloDerm™ RTM is made of. 1,*

Table of Contents

On Their Own:

Where did their residency program go? . . . . . . . . . 5

Residents unexpectedly found themselves without a training program, but resident leaders and others are bringing lifelines.

Consult Corner:

Gender-affirming genital surgery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

“Bottom” surgery can alleviate gender dysphoria and improve transgender patients’ quality of life.

Complex Case Challenge:

Traumatic left-flank wound . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

An 18-year-old male sustains a crush injury to his side after being pinned between two trucks; what’s your treatment approach?

Program Peek:

Harvard Mass General Brigham Plastic Surgery . . 12

This prestigious institution lays claim to some of the world’s top plastic surgeons and groundbreaking innovations.

Message From the Director:

Kyle Eberlin, MD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Growing collaborations and mentorship – and a wide spectrum of opportunities – help residents realize their potential.

Faculty Focus:

Kavitha Ranganathan, MD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Challenges, a strong mentor and preparation are key ingredients for success as a plastic surgery resident.

24 Hours in: Boston . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

“The quintessential New England city” and its popular offerings await residents in Boston during Plastic Surgery The Meeting.

Future Direction: Q&A with The PSF President . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

Bernard T. Lee, MD, MBA, MPH, discusses The PSF’s reach, academic plastic surgery’s future and resident contributions.

Dear Abbe:

My complication vexes me . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Gaining meaning, solace and personal forgiveness when your trusting patient suffers a serious complication.

InService Insights: Liposuction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Important exam concepts are highlighted for the nation’s fourth most-popular cosmetic surgical procedure.

Journal Club: Ergonomics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Ten journal articles are presented to help increase efficiency –and build better health – in clinic and the O.R.

International Perspective: Dispatch from Finland

. 26

Virve Koljonen, MD, PhD, the sole plastic surgery professor in Finland, on how social media figures into her teaching mission.

ASPS Legislative Conference 2022: Engagement on Capitol Hill

Ravi Viradia, MD, and Michael Hu, MD, MPH, MS, share highlights from two days of meetings with lawmakers in Washington, D.C.

Plastic Surgery Perspectives: Microsurgery, Part V

28

Joseph Dayan, MD, describes his path to microsurgery – and to lymph node, facial nerve and breast reconstruction.

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 | Vol.6 N o.3

The mission of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons is to support its members in their efforts to provide the highest quality patient care, and to maintain professional and ethical standards through education, research and advocacy of socioeconomic and other professional activities.

ASPS PRESIDENT

J. Peter Rubin, MD, MBA | rubipj@upmc.edu

EDITOR

Russell Ettinger, MD | retting@uw.edu

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Joseph Lopez, MD | joeyl07@gmail.com

SENIOR RESIDENT EDITOR

Megan Fracol, MD | mfracol@gmail.com

RESIDENT EDITORS

Michael Hu, MD, MPH, MS | hums2@upmc.edu Harry Siotos, MD | Charalampos_Siotos@rush.edu

Ravi Viradia, MD | rviradia1@gmail.com

INTERNATIONAL RESIDENT EDITOR Monica Zena, MD | monicazena1@gmail.com

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT Michael Costelloe | mcostelloe@plasticsurgery.org

STAFF VICE PRESIDENT OF COMMUNICATIONS Mike Stokes | mstokes@plasticsurgery.org

MANAGING EDITOR Paul Snyder | psnyder@plasticsurgery.org

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Jim Leonardo | jleonardo@plasticsurgery.org

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Kendra Y. Mims | kmims @plasticsurgery.org

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Jun Magat

ADVERTISING SALES

Michelle Smith (646) 674-5374 | Wolters Kluwer Health

Plastic Surgery Resident (ISSN 2469-9381) is published four times per year and distributed free to members of the ASPS Residents and Fellows Forum and plastic surgery training programs. Letters, questions or comments should be addressed to: Editor, Plastic Surgery Resident, 444 E. Algonquin Road, Arlington Heights, IL 60005.

The views expressed in articles, editorials, letters and other publications published by Plastic Surgery Resident (PSR) are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of ASPS. Acceptance of advertisements for PSR is at the sole discretion of ASPS. ASPS does not guarantee, warrant or endorse any product, program or service advertised.

ASPS Home Page: www.plasticsurgery.org

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A note from the editor

Russell E. Ettinger, MD Chief Medical Editor Plastic Surgery Resident Seattle

Russell E. Ettinger, MD Chief Medical Editor Plastic Surgery Resident Seattle

Welcome to our Plastic Surgery the Meeting 2022 (#PSTM22) fall issue of Plastic Surgery Resident

We welcome you to the host city of Boston, and we start by highlighting the storied Harvard Plastic Surgery program, which is steeped in the history of surgery in America and the source of numerous contributions to plastic surgery. As part of their program’s feature, Harvard residents graciously provided us with a list of attractions in the vicinity of the Boston Convention Center so that you can take in some of the city’s offerings during your downtime, as well as several others of historical or cultural significance that are but a short Uber ride away.

Last year, our field was affected by the closure of two plastic surgery training programs, and while this was a shock to all, it galvanized efforts to support residents who suddenly found themselves without a program. Following the closures, the ASPS Residents Council, with the backing of the Society’s leadership, led the charge to advocate for improvements in plastic surgery resident support systems. Our cover story provides an update from ASPS Residents Council members on the group’s ongoing efforts, as well as commentary from residents who re-established their training at new programs following the closures.

In this issue, we also provide updates from our PlastyPAC Resident Ambassadors who attended the ASPS Legislative Conference in Washington, D.C., as they address the importance of advocacy for the specialty in national healthcare policy. Our recurring pieces include a Consult Corner on genderaffirmation surgery; Journal Club on surgical ergonomics; In-Service Insights on liposuction; and our International perspective showcasing the use of social media to help educate medical students and residents in Finland. You will also find our Complex Case Challenge, which presents a multilayer abdominal injury with expert insights from attending surgeons from around the country. Finally, please enjoy the latest installment of Dear Abbe, which features advice on how to stay positive when our patients suffer complications.

As always, we thank our readers, our team of editors and the ASPS production staff. We hope you enjoy the read! |

4 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Fall 2022

THE HUMAN COSTS OF DISSOLUTION

Sudden closure of residency programs creates chaos – and opportunity

By Michael Hu, MD, MPH, MS

Members of the Accredita tion Council for Gradu ate Medical Education’s (ACGME) Residency Review Committee (RRC) in March 2021 visited the plastic surgery residen cy programs at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland and University of Tennessee Health Sci ence Center (UTHSC) in Memphis, presumably to discuss with officials topics such as work hours, case details and other phases of those residency programs.

But without warning, the RRC on April 9, 2021, announced that it was withdrawing accreditation from both programs. As neither program had been placed under probation, this announce ment came as a shock to many – and created exceptional career and personal turmoil as well as uncertainty for the 22 active and three prospective trainees who were suddenly displaced from their systems – and therefore separated from their support.

They were left to find positions at other programs that would allow them to continue training, some were unable to communicate with their program direc tor and/or chief and others were pulled from their rotations.

Eleven days after the RRC announce ment, the ASPS Residents Council held a meeting that resulted in a position statement released in May 2021 to the leaders of ASPS, American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons (ACAPS), RRC and Internal Review Committee (IRC) of the ACGME.

The challenges faced by the displaced residents brings to light myriad ques tions:

• How can such events be prevented in the future?

• Can the process of withdrawal of accreditation be improved?

• Can there be a streamlined process for displaced residents to find another program?

• Do the ramifications surrounding a loss of accreditation influence resi dents to conceal serious issues in their program?

A perfect solution for such a disruptive event may never be found. In the mean time, in an effort to provide takeaways from which to learn and to improve the process, two leaders of the ASPS Resi dents Council who’ve become immersed in gathering data and finding solutions, and two residents displaced by program closures, have agreed to share their insights and experiences with Plastic Surgery Resident.

Cristin Coquillard, MD PGY-5, now at Northwestern University

More than a year has passed since the closure of my plastic surgery residency program at CWRU – and I view it as one of the best things that happened to me. However, the period of April-Au gust 2021 was the most stressful time I’ve ever experienced.

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 5

SUDDEN PROGRAM CLOSURES / continued from previous page

My co-residents and I discovered our accreditation was withdrawn when we checked the ACGME website on my son’s first birthday – coincidentally, April 9, 2021. Questions and specu lation about our futures dominated our thoughts, and most conversations seemed to lack any good (or reliable) information. Would we be able to find new spots? How would we find them? Would we keep our funding? Would we have to repeat any time? How would this affect our graduation and ability to apply to fellowships? Our whole lives were in a state of upheaval.

Several days passed before we received any official notification of our closure –and more than a week passed before any meetings occurred with the hospital or GME leadership. To its credit, CWRU did the best thing they possibly could for us – they let us keep our funding, which made finding new positions infinitely easier for the Case Western residents. However, we were essentially told that we were on our own when it came to finding new spots. It was a tumultuous time for all of us by any and all measures.

The ASPS Residents Council stepped in after learning of the issues being faced by our program and at UTH SC. We soon began to hold meetings between all the displaced residents and the Residents Council. The most helpful thing that came out of these meetings was a list of and contact information for programs that could accommodate an additional resident. For the first time since the news broke, we felt supported and heard.

Given how late we were notified of our loss of accreditation, I didn’t officially have a spot in another program until mid-May. My husband, 1-year-old son and I had less than six weeks to sell our house in Cleveland, buy a house in Chicago, physically move, figure-out childcare in a new state and complete the onboarding and licensing for a new

hospital – all while both working fulltime in our current jobs.

My husband had to stay in Cleveland for an extra month, which meant we couldn’t get a house in Chicago by my July 1 start date. My son and I lived alone for a month in temporary housing more than 30 minutes away from the hospital. This challenge came on top of the already unnerving situation of navigating an entirely new hospital system in the absence of the support one normally receives as an intern. I also lost all my research projects that were in progress at my old program because I no longer had access to the EMR and faculty support there. It was an incred ibly stressful time and a huge financial burden. Looking back, I still don’t know how my family got through it.

Still, the story has a happy ending. I’m extremely pleased with my current situ ation and feel fortunate for the opportu nity to train at one of the best programs in the country.

However, the journey to this point was something that I wouldn’t wish upon my worst enemy. I hope that no other plastic surgery programs close in the future, but I appreciate the steps the Residents Council is taking to make the process easier in the future and to protect the residents who must go through it.

The most important of those initiatives are to ensure that displaced residents keep their funding, and for programs to receive notification of accreditation withdrawal much earlier – so that prospective residents do not match into closed programs and are allowed ample time to find other spots to relocate.

Megan Fracol, MD Chair, ASPS Residents Council

When I began as chair of the Residents Council, our first group meeting oc curred in Atlanta during Plastic Surgery The Meeting 2021. The majority of the meeting, which was one of the high est-attended Residents Council gath erings ever, was devoted to discussing the recent program closures – and we’ve spent the time since initiating several efforts to combat issues faced by many of the residents displaced by program closures.

Three major projects are currently underway:

1. Interviews of displaced residents for information gathering. These are being conducted largely by Residents Council members Matthew Pontell, MD, and Arya Akhavan, MD, under the faculty guidance of Brian Drolet, MD. There are multiple purposes to these interviews, including under standing the challenges displaced residents faced in finding new pro grams, how the events affected their families – and what resources would be useful to streamline the process. We also hope to describe the experi ence of displaced residents in order to emphasize to governing bodies how much the program closures affected them, such that the gravity of these closures can be better-understood and anticipated in the future.

2. An ACGME Residency Review Committee petition. The goal of this petition is to request that the timeline for RRC meetings be moved earlier in the year, such that decisions on program closures or suspensions

6 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Fall 2022

can be available earlier in the year. This would allow sufficient time for displaced residents to find new positions and prevent prospective res idents from matching to a program that’s about to be shut down.

3. Develop a resource book for displaced residents. Prior to the program closures in 2021, it had been a long time since the last program closure. Many of the displaced residents felt there was a lack of guidance on how to go about finding new programs and how to navigate the transition phase. To that end, we’re working on a resource guide that includes point-people for various steps of the transition process.

Although we hope that no one ever has to endure the process of a plastic surgery residency program closure, we’re nevertheless working to ensure the process is smoother, should it occur. I would like to send a huge thank you to the Residents Council members who have helped in these efforts this year. Particular thanks goes to Drs. Pontell and Akhavan; Pablo Padilla, MD; Janak Parikh, MD; Anthony Colon, MD; Avra Laarakker, MD; Sameer Massand, MD; and Eugene Zheng, MD; for their time on the program closures working group. Also a big thank you to the res idents from CWRU and UTHSC for giving us insight into their experiences.

done so following a predictable process of working through college, medical school and residency. Applications for each step are done in an orderly process and, while working through it, you always had a sense for what was to come next and what contingencies were avail able should things not fall into place.

The closure of a residency program is a massive departure from this paradigm – in large part because they are rare occurrences. When we first received the news of the CWRU closure, I per formed a Google search to find exam ples of others that had been through similar situations. There wasn’t much information to be found. My fellow res idents had a lot of questions on how to reach out to programs, what to do with incoming interns that had matched but not started, how to navigate funding, how to navigate leases on homes and how to logistically handle the process of moving and onboarding over the span of several months.

The ASPS Residents Council inter vened and, as Dr. Fracol noted, began holding meetings with us to trouble shoot problem areas (including reaching out to programs to identify points of contact for programs that had avail ability and disseminating this infor mation to us via ACAPS, social media and program contacts). The council also initiated advocacy efforts with the AMA to help ensure that resident funding followed us; submitted propos als to ensure the earlier notification of program closures in the future, in order to avoid having medical students match into programs that may be closing; and proposed a host of solutions for travel logistics, training requirements and several other areas of impact.

Arya Andre Akhavan, MD ASPS Residents Council’s Program Closures Subcommittee

Every year, residents across the United States send information to the AC GME regarding their residency pro grams and any potential issues that may exist. Programs are often able to address these issues, but in some cases, repeated issues or direct resident reports might result in programs receiving warnings or probationary status. A direct program closure, however, is rare.

That’s why the ASPS Residents Council called an emergency meeting in April 2021 in the wake of the sudden closure of the CWRU and UTHSC residen cy programs. Even a single program closure within plastic surgery is exceed ingly rare, but two at the same time is unheard of. Given that there are 5,380 residency programs in 31 specialties, one would expect that some type of resource or guide exists for displaced residents; therefore, we were surprised to find that no such thing exists. How exactly were these displaced residents supposed to know what to do?

Brandon De Ruiter, MD PGY-3, now at University of Washington

One of the most daunting aspects of the transition after closure of my CWRU residency program was the lack of pro tocol. I think anyone who has reached this point in their medical training has

Much of this work is ongoing. Still, having these protocols in place in the event this should ever happen to anoth er program – regardless of specialty – is immeasurably important.

The ASPS Residents Council formed a subcommittee specifically targeting program closures and these displaced residents, and then began work on several fronts – the first of which was navigating the placement process. The funding behind a position is complex and transferring this funding from one institution to another is byzantine. As it turns out, hospitals aren’t even obligated to transfer the positional funding when a program closes, and the receiving GME offices often are unsure of how to accept the funding.

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 7 continued on page 30

Gender-Affirming Genital Surgery

“Consult Corner” addresses a consult commonly encountered by an on-call resident. The column begins with the reason for consult and assesses questions that might go through a resident’s mind as he or she heads to the emergency department to see the patient. Key aspects of the history and physical, as well as additional testing that should be obtained, are also presented. Finally, a review of the decision-making process will present possible management strategies, all of which are synthesized into the context of an actual case.

By Brandon Alba, MD; Brielle Weinstein, MD; Charalampos Siotos, MD; & Loren Schechter, MD

You’ve been called to the E.R. to assess a 37-year-old trans male who’s four months post-phalloplasty with urethral lengthening and complains of fever and foul-smelling urine.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Gender-affirming genital surgery, often referred to as “bottom” surgery, is an important means of alleviating gender dysphoria and improving quality of life for many transgender patients. Plastic surgery residents should be familiar with the most common postoperative complications, including evaluation and management. Cultural competency and awareness are important. People should be addressed by the appropriate pronouns; if unsure which pronouns to use, it’s best to inquire. Gender-affirming surgery typically involves a multidisciplinary team composed of plastic surgeons, urologists, endocrinologists, primary care professionals, mental and behavioral health professionals, physical therapy and social workers, among others.

VAGINOPLASTY

Gender-affirming vaginoplasty typical involves penectomy, orchiectomy, clitoroplasty, vulvoplasty and the construction of a neovaginal canal. Currently, the most commonly used method for creation of the neovaginal canal involves penile inversion, often with supplemental scrotal skin grafts. Residents should be familiar with the regional anatomy and surgical techniques.

Other than aesthetic revision, postoperative bleeding is the most common reason for reoperation, with 0.3-0.5 percent of patients requiring a return to the O.R. for hemorrhage or hematoma. Post-op bleeding has been reported in 3.2-12 percent of

8 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Fall 2022

Brandon Alba, MD

Charalampos Siotos, MD Loren Schechter, MD

Brielle Weinstein, MD

patients, with 1.6-21 percent experiencing hematoma. Often, the highly vascular spongiosal tissue encasing the urethra is the source of bleeding. While some bleeding may require a return to the O.R. for source control or hematoma evacuation, most bleeding can be controlled with bolster or pressure dressings.

Perhaps the most concerning complication is rectal injury. This may occur during dissection of the neovaginal canal or, secondarily, from cautery injury. Rectal injury may progress to a rectovaginal fistula. A fistula presents as air or stool in the neovaginal canal. Rectal injuries have been reported in 0-6.7 percent of cases. Management entails layered closure of the defect. Rectovaginal fistulae are reported to occur in 0-17 percent of patients. Fistulae may affect the ability to dilate the vaginal canal – and inability to dilate the vaginal canal may result in subsequent vaginal stenosis or loss of the canal.

Surgical site infections have been reported in 0-27 percent of patients. Most infections are treated with oral antibiotics and don’t require surgical drainage. Minor wound-healing issues are reported in 3.3-33 percent of patients and tissue loss is reported in 0.624.6 percent of patients. Wound disruption and/or tissue loss are typically treated with local wound care.

Perioperative urinary complications include urinary tract infection (4.4-7 percent), urinary retention (0-12.8 percent) and urethral injury (0-1.1 percent). Long-term urinary issues include meatal stenosis, occurring in 0-6 percent of patients, which may require urethral dilation or urethroplasty. An estimated 3.3-7 percent of patients may also present with urinary incontinence, typically managed with anticholinergic medications or pelvic floor physiotherapy.

Perioperative management of hormone replacement therapy varies between centers. The incidence of VTE after vaginoplasty is reported at 0-6 percent. VTE risk reduction measures such as mechanical compression devices, early ambulation and chemoprophylaxis may be utilized, although regimens vary between centers.

PHALLOPLASTY

The most common phalloplasty technique is either the radial forearm or anterolateral thigh flap. Flap monitoring is similar to other flaps and includes monitoring for signs of congestion, arterial insufficiency or hematoma.

Urinary complications (stricture and/or fistula) associated with urethral reconstruction (typically a “tube within a tube”) are reported as high as 70 percent. Evaluation may include urologic consultation, retrograde urethrography (RUG) or voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) and/or cystoscopy. Urinary fistulae occur in 15-70 percent of patients; those that persistent beyond three months or are too large to spontaneously close typically require surgical repair. Urethral stricture rates are reported as 25-58 percent, most commonly in the anastomotic portions of the urethral

reconstruction. Strictures often require urethroplasty – either direct excision and closure or staged repair with urethral augmentation.

CLINICAL SCENARIOS

On postoperative Day Two following vaginoplasty, a 28-year-old trans woman started experiencing lower abdominal pain. The differential diagnosis for lower abdominal pain after vaginoplasty includes hematoma, urinary retention, ileus and, possibly, rectal injury. History-taking should include onset; duration; character and intensity of symptoms; presence of systemic symptoms (fatigue, dizziness/lightheadedness, fever, nausea/vomiting); urine and drain (if present) outputs; and bleeding or discharge from the surgical site.

Physical exam includes inspection of the surgical site; checking bleeding; wound-disruption infection (erythema, crepitus, swelling, fluctuance, discoloration); peritoneal signs; and/or suprapubic tenderness. If bleeding is noted, it’s most often from the clitoris and/or urethra. Direct pressure is helpful, although return to the O.R. may be required. CT imaging may be required to assess for bleeding within the pelvis. A CBC should be ordered if bleeding is suspected. Rectal injury with rectovaginal fistula will present as stool and air in the vaginal canal. Urinary retention may manifest as lower abdominal pressure. A bladder scan and assessing foley position (i.e., no kinks or clots) should be performed. If a Foley catheter is present, dependent drainage of the catheter is facilitated by standing the patient and inline positioning of the catheter. Medications such as oxybutynin and tamsulosin may be prescribed to, respectively, manage bladder spams and relax the urethral sphincter.

Returning to the 37-year-old trans male who led this column, malodorous urine and fever are highly suggestive of urinary tract infection (UTI). History-taking should include urinary symptoms (i.e., increased time or increased straining to void, weakening of the urine stream, incomplete emptying, urinary frequency, etc.). Physical exam includes assessing for suprapubic and flank tenderness. The neophallus should be inspected for fistula, erythema or abscess. A urinalysis and culture should be collected, and empiric antibiotics should be considered. Infectious disease and urology consults can be considered. If there are concerns for fistula and/or stricture, evaluation of the urinary tract with cystoscopy, retrograde urethrogram or voiding cystourethrogram may be necessary. Small fistulae may be treated with local woundcare but may be a sign of distal urethral obstruction. |

Dr. Alba is in a Research Year as an integrated plastic surgery resident at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago; Dr. Weinstein is a Fellow in Gender Affirmation Surgery at Rush; Dr. Siotos is PGY-4 as an integrated plastic surgery resident at Rush; and Dr. Schechter is director of Gender Affirmation Surgery at Rush.

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 9

COMPLEX CASE CHALLENGE

Welcome

PATIENT PRESENTATION

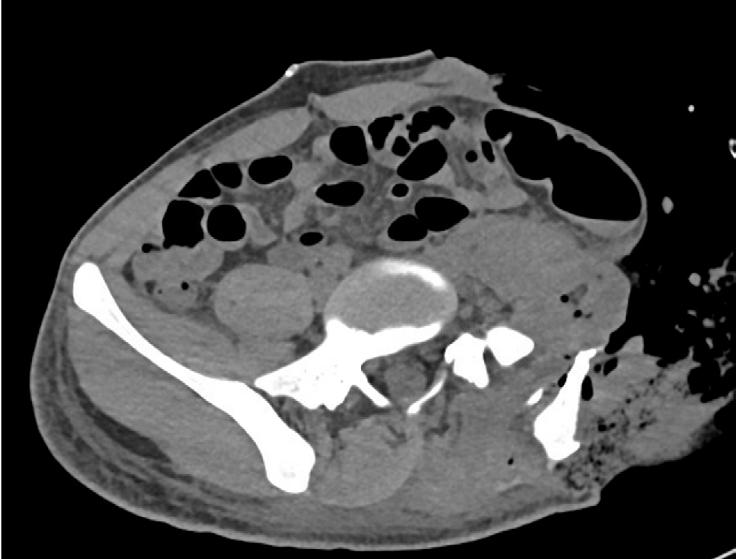

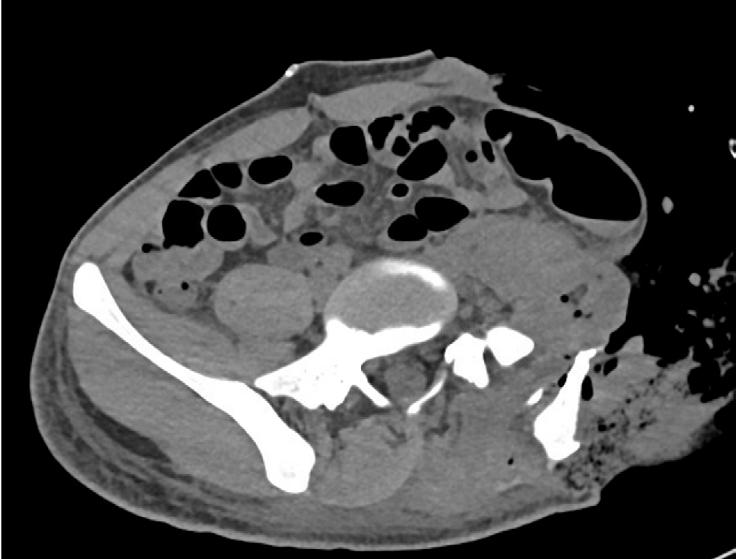

Plastic surgery is consulted for complex abdominal wall reconstruction for a traumatic left-flank wound. The patient is a healthy, 19-year-old male who suffered a crush injury after being pinned between two garbage trucks. His major acute injuries include left splenectomy, colon injury, multiple rib fractures, left lung injury, open unstable left-pelvic fracture and extensive full-thickness soft-tissue loss of the left-flank region. After initial intubation, operative washout and exploration, repair of intra-abdominal injuries and chest tube placement at an outside hospital, he’s transferred to another facility for a massive left-flank wound reconstruction and orthopedic management of left open unstable pelvic fracture. There he undergoes washout and debridement of left flank and wound vac placement by plastic surgery, and orthopedic surgery places a pelvic external fixator. Left-flank wound is found to be full thickness from the semilunar line to the posterior axillary line, with only the peritoneal lining intact and containing abdominal viscera. He also has a left-femoral nerve avulsion injury.

TREATMENT

Day 1: Injury and admission to the outside hospital, where he underwent emergent ex-lap: splenectomy, primary repair of colon injury, left-flank debridement, plating of 6 and 8 ribs, chest tube placement

Day 4: Date of transfer to other facility

Day 5: Date of washout at outside hospital, irrigating wound vac placement by plastic surgery and temporary external pelvic fixation by orthopedics

Day 7: Repeat washout and wound vac changed, antibiotic bead placement and anterior pelvic external fixator placed by Orthopedic surgery, Urology performed flexible cystoscopy, retrograde urethrogram, bilateral retrograde pyelogram, and no evidence of injury to collecting system or urethra bilaterally

Day 11: Plan for definitive plastic surgery soft closure of left-flank wound

MAIN RECONSTRUCTION CONSIDERATIONS

• Adequate soft-tissue coverage left flank for coverage of open pelvic fractures, hernia prevention and quality of life (timing, requirements and methods)

• Left-femoral nerve avulsion

• Working with orthopedic surgery regarding open pelvic unstable fracture

• Flank hernia repair (timing, requirements and methods)

PREOPERATIVE CLINICAL PHOTOS

If you have a complex case that you would like to feature, please email

PSR Medical Editor Russell Ettinger at retting@uw.edu

10 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Fall 2022

to another edition of our Complex Case Challenge, also known as “C3,” wherein we present a challenging case to get your reconstructive mind working! Read on, and you’ll find a challenging clinical vignette along with several options for reconstructive solutions. Make note of your choice – and make sure you read the next issue of

Plastic Surgery Resident magazine to see the authors’ ultimate management of this case. For this case, we thank Ava Chappell, MD; Jennifer Bai, MD; and Gregory Dumanian, MD.

A B C

PREOPERATIVE IMAGING

D

F G

A) Anterior Trunk

B) Oblique Trunk

C) Lateral Trunk

D) X-ray AP, Supine in Traction

E) CT Abdomen, Pelvis Axial F) Sagital G) Coronal

ECOMPLEX CASE SOLUTIONS

The perspective of Jeffrey Janis, MD

I would make sure we had culturenegative debridement before proceeding; once accomplished, I would get a pre-op CT angiogram to confirm patency to the descending branch of lateral femoral circumflex artery, given the extent of the crush injury.

Then, I would do a reverse Gillies maneuver to see if a pedicled ALT – or, better yet, a subtotal thigh flap – would work. (It may be hard to reach the superior aspect without a subsartorial transposition or, even so, you may need a possible free flap.)

The flap would definitely require back-grafting to the donor site, given the size. I’d use incisional NPWT around the incision while still being able to visualize and monitor the flap.

The surgeon could use biologic mesh in-between the viscera and the flap, though that will certainly bulge over time – and I don’t think it would add much to the result besides cost. I wouldn’t put synthetic mesh into a wound like that at the index operation, however, for fear of risk of mesh infection. |

Dr. Janis is president of the American Hernia Society, editor-in-chief of PRS Global Open and an ASPS past-president.

Dr. Baumann is a professor of plastic surgery at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

The perspective of Donald Baumann, MD

I would separate the abdominal problem from the rest of the problem. First, I would address the abdomen by closing-off the belly with a biologic mesh. It’s unlikely he will herniate because the degree of inflammation to the viscera is similar to a radiated patient, so everything should be sucked in. However, if he does end up herniating, I would come back in delayed fashion to perform an innervated free latissimus. With this in mind, I would tag any intercostal nerves at the initial stage, in case we need to come back for that.

Next, I would consider the status of the femoral nerve. If it’s not reconstructable, then I would do a pedicled left thighbased flap for skin closure of the abdomen. If the femoral nerve is reconstructable, then I would stay away from the left thigh as a donor site and use the right thigh donor site as a free flap. The options for recipient vessels – depending, of course, on CT studies – would be something from the femoral system with or without an AV loop.

In summary, I would compartmentalize things: Close off the belly, then vac until ready for next operation. Next, consider whether he may have femoral nerve recovery. Next, come back for skin closure with regional versus free thigh-based flap – or possibly innervated latissimus flap. |

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 11

Harvard Mass General Brigham Plastic Surgery

By Vishwanath Chegireddy, MD, & Charles Hwang, MD

By Vishwanath Chegireddy, MD, & Charles Hwang, MD

Charles Hwang, MDVishwanath Chegireddy, MD

HISTORY

John Collins Warren, MD, repairs palatal defects at Massachu setts General Hospital in the early 1800s. Years later, his son, Jonathan Mason Warren, MD, performs one of the first rhino plasties in America.

William E. Ladd, MD, pioneers plastic surgical techniques for congenital anomalies and becomes a founding member of the American Board of Plastic Surgery and the American Associa tion of Plastic Surgeons.

Varaztad H. Kazanjian, MD, becomes one of the first leaders at the combined Plastic Surgery Clinic of Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and the Massachusetts General Hospital. In 1941, he becomes the first professor of plastic surgery at Harvard Medical School.

Bradford Cannon, MD, an international expert on the care of burn patients, begins the first plastic surgical training program at MGH in the early 1960s. In 1971, he becomes the first chairman of the Plastic Surgery Residency Program at MGH.

Joseph E. Murray, MD, performs the world’s first successful organ transplantation at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in 1954. Shortly after, he performs the world’s first successful allograft (1959) and the world’s first cadaveric renal transplan tation (1962). In 1990, Dr. Murray’s awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Julian Pribaz, MD, serves as the first program director of the Harvard Plastic Surgery Combined Residency Training Program in 1999 after the merger of three pre-existing Harvard-affiliated training programs.

PROGRAM LEADERSHIP

William G. Austen Jr., MD: Professor of Surgery; Chief, Divi sion of Plastic Surgery; Chief, Division of Burn Surgery; Interim Chief, Division of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery at MGH

Andrea Pusic, MD, MHS: Professor of Surgery; Chief, Divi sion of Plastic Surgery; Director of Patient-Reported Outcomes, Values & Experience Center at BWH

Branko Bojovic, MD: Assistant Professor of Surgery, Chief, Division of Plastic Surgery at Shriner’s Hospital

John Meara, MD, DDS: Professor of Surgery; Steen C. and Car mella R Steven C. and Carmella R. Kletjian Professor of Global Health and Social Medicine in the Field of Global Surgery; Plas tic Surgeon-in-Chief, Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery

Kyle Eberlin, MD: Associate Professor of Surgery; Program Di rector, Harvard Mass General Brigham Plastic Surgery Residen cy; Associate Program Director, MGH Hand Surgery Fellowship

Lydia Helliwell, MD: Instructor of Surgery; Associate Program Director, Harvard Mass General Brigham Plastic Surgery Resi dency

Devin O’Brien Coon, MD: Fellowship Director, BWH Com plex Gender and Microvascular Surgery Fellowship

Ian Valerio, MD: Fellowship Director, MGH Peripheral Nerve and Microsurgery Fellowship

Jessica Erdmann-Sager, MD: Fellowship Director, BWH Breast Microsurgery Fellowship

Christian Sampson, MD: Fellowship Director, BWH Stepping Strong Hand Surgery Fellowship

NATIONAL LEADERSHIP

William G. Austen Jr., MD: President of the Migraine Surgery Society

Andrea Pusic, MD, MPH: Director of Patient-Reported Outcomes, Values & Experience Center at BWH, Past President of The Plastic Surgery Foundation; ASPS/PSF Board of Direc tors; Co-Founder, SHARE program; Co-Chair, National Breast Implant Registry

Amy S. Colwell, MD: Co-Editor, PRS; Chair, ASPS Spring Meeting; Co-Chair, AAPS Reconstructive Symposium; CoChair Breast ASPS Spring Meeting

Jonathan Winograd, MD: President, Massachusetts Society of Plastic Surgeons; Secretary and Executive Board member, Ameri can Society of Peripheral Nerve

Kyle Eberlin, MD: Hand/Peripheral Nerve Section Editor, PRS; Peripheral Nerve Section Editor, PRS Global Open; Traveling Fel low, American Society of Peripheral Nerve; Board of Directors, American Association for Hand Surgery; Board of Directors,

12 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Fall 2022

American Society of Plastic Surgeons; Chair, AAHS Technology Committee; Chair, ASSH Emergency Hand Care Committee.

Arin K. Greene, MD: President, New England Society of Plastic Surgeons; President-Elect, Plastic Surgery Research Council; Editorial Board, Journal of Craniofacial Surgery; Associate Editor, Journal of Vascular Anomalies

Dennis Orgill, MD, PhD: Chair, ASPS Annual Meeting Coun cil and the Annual Meeting Educational Program Committee; Board of Directors, Wound Healing Society, Hidradenitis Foun dation; International Society of Plastic Regenerative Surgeons; AAPS Visiting Professor

Simon Talbot, MD: Vice Chair, ASPS Hand Work Group; Chair, AAHS Research Committee; Board of Directors, Development Committee Chair, Pro gram Committee Chair, American Society for Reconstructive Transplan tation; Steering Committee, International Society of Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation

Devin O’Brien-Coon, MD: Chair, Gender-Af firming Surgery Task Force, American Society of Plastic Surgeons

Carolyn Rogers-Vizena, MD: Vice President of Socioeconomic Affairs, American Society of Maxillofacial Surgeons; Associate Editor, PRS Global Open; ASMS Representative to the ASPS/ PSF Board of Directors

Kavitha Ranganathan, MD: Vice-President, ASPS Young Plas tic Surgeons Steering Committee

Amir H. Taghinia, MD: Associate Editor, Journal of Hand Sur gery Global Online and Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery

*Multiple Board Examiners Among Faculty

CLINICAL EXPERIENCE

The Mass General Brigham Harvard Plastic Surgery program includes 24 residents in both integrated and independent tracks, and provides a comprehensive education and training in plastic surgery. The program consists of more than 30 faculty members with diverse clinical interests. Residents rotate at the nation’s pre mier teaching hospitals: Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH); Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH); Boston Children’s Hospital; Shriners Hospital for Children; and Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. These hospitals provide more than 2,000 inpa tient beds combined. Chief residents manage their own aesthetic and reconstructive clinics at both BWH and MGH.

MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL: Dr. John Collins Warren, Dr. Jonathon Mason Warren, George H. Monks, MD, Dr. Kazanjain and Dr. Cannon characterized the beginning of plastic surgery at MGH. Consistently ranked at the top of the list of best hospitals in the world, MGH serves as a leader in research, with more than $1 billion in research operations and roughly 1,200 clinical trials taking place at any given time. The hospital serves as a regional, national and international epicenter for medical care. Residents cover the vast breadth of plastic sur gery, with emphasis on complex reconstruction, peripheral nerve and cosmetic procedures.

BRIGHAM AND WOMEN’S HOSPITAL: Dr. Ladd, Dr. Murray, John Homans, MD, and Donald MacCollum, MD, encompass the foundational history of plastic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Also consistently ranked as one of America’s best hospitals, BWH is the second-largest NIH-funded hospital in the country and home to pioneering medical milestones, including organ transplantation and mitral valve surgery. Residents engage in all aspects of plastic surgery with emphasis on wound healing, craniofacial surgery, gender-affirmation surgery and microsurgery.

BOSTON CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL: Children’s Hospital provides an expansive curriculum on craniofacial and pediatric fo cused plastic surgery. As the top children’s hospital in the country, residents are immersed in an integrated plastic and oral surgery service to care for patients with cleft lip/palate, craniofacial anomalies, and congenital hand and facial reanimation needs.

SHRINERS HOSPITAL FOR CHILDEN: Shriners Hospital in Boston is a leader in pediatric burn care and the only exclusive ly pediatric burn center in New England. Residents also further reinforce their pediatric surgery training by incorporating cleft lip and palate care, as well as general reconstructive and plastic surgery.

EDUCATIONAL CURRICULUM

The Harvard MGB PRS Program contains a weekly inte grated didactic curriculum in conjunction with the BIDMC Program. In addition to weekly lectures by esteemed faculty, a core component of these weekly didactics are peer-led, with seminars steered by PGY-1 to PGY-6 residents on a rotating basis. Objectives include provision of a comprehensive review of test-relevant topics that align with ASPS educational learning

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 13

objectives and In-Service literature. In a blended, flipped class room model, residents are guided on relevant, primary literature assignments with rapid review. This valuable in-person time is predominantly reserved for Socratic seminars with a focus on enrichment and clarification of surgical or anatomical concepts. In alignment with contemporary pedagogical theory, this educa tional structure also organically incorporates teaching opportu nities for all levels of residents, with peer feedback on teaching and presentations. From the most junior to senior, MGB PRS residents refine their teaching and academic development as a foundational component of their residency training. The new didactics structure has rapidly become a major highlight with program-wide engagement.

RESIDENT BENEFITS

One of the significant strengths of the MGB program is the integra tion across multiple institutions across the primary flagship hospitals (BWH, MGH and BCH) as well as community/satellite campuses.

PGY-1 residents undergo early exposure to PRS rotations for two months in the intern year during their general surgery internship.

PGY-2 residents begin their transition into plastic surgery with several additional enrichment rotations – including dermatology, anesthesia, SICU and OMFS, along with eight months of plastic surgery.

PGY-3 residents rotate full-time in plastic surgery, including at Children’s Hospital for a foundational exposure to pediatric plastic surgery.

PGY-4 residents further reinforce more complex management principles across oculoplastics and ENT rotations at Mass Eye and

Ear Infirmary, as well as burn reconstruction at Shriners Hospital, in addition to their primary plastic surgery rotations.

PGY-5 residents serve as administrative chiefs, running each major adult hospital’s service, with a particular focus in microsurgery and surgical planning.

PGY-6 chief residents staff independent clinics with a focus on the junior-attending transition with more nuanced surgical planning, pa tient selection and intraoperative teaching. Chief residents at MGH and BWH have their own operative “blocks” and able to schedule surgical cases with faculty oversight.

Throughout these academic years, there are integrated longitudinal curricular experiences as well:

• Chief reconstructive and cosmetic clinic

• Cosmetic/injectables clinic

• Anatomy cadaver labs

• Global surgery service trips (Europe, Africa and Asia)

• Residency socials – boat cruise, Christmas party, summer party and change show

Outside of the hospital, residents remain busy across a multitude of hobbies and interests: We have hikers, triathletes, golfers, hunters, fishers, sailors, music aficionados, chefs, photographers, artists, Pelo toners, Karaoke fanatics, rock climbers, skier/snowboarders, weekend warriors, Olympic athletes – and professional diners. |

Dr. Chegireddy is PGY-6 and Dr. Hwang is PGY-3 in the Harvard Mass General Brigham Plastic Surgery Residency Program.

14 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Fall 2022

A Message From the Program Director, Kyle Eberlin, MD W

e are immensely proud of our Mass General Brigham Harvard Plastic Surgery Res idency Program, which has a storied legacy and a bright future. Harvard has a notable history within plastic and reconstructive surgery: At Boston Children’s Hospital, Wil liam E. Ladd, MD (1880-1967), was a pioneer pediatric surgeon who devised plastic surgical techniques for congenital anomalies – and he was a founding member of the American Board of Plastic Surgery and the American Association of Plastic Surgeons. Varaztad H. Kazanjian, MD (1879-1974), graduated from Harvard Dental School in 1905 and became an authority on the management of mandibular fractures through his development of the intermaxillary wiring method of fixation. He helped formally develop the Division of Plastic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), which was established in 1971. Nobel Laureate Joseph E. Murray, MD, developed the first formal plastic surgery training program in Boston in 1967 at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and Children’s Hospital – and he used performed the world’s first solid organ (kidney) transplant.

The Harvard Plastic Surgery Training Program was formed in 1999 by combining the programs at Brigham and Women’s/Children’s Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and MGH. Julian Pribaz, MD, served as the program director from its inception and was succeeded in 2010 by Michael Yaremchuk, MD, who led the program for more than 10 years. In 2020, I was appointed program director to the new Mass General Brigham Harvard Plastic Surgery Program along with Associate Program Director Lydia Helliwell, MD – and we’re excited to con tinue the long tradition of educational excellence and innovation within plastic surgery in Boston.

Residents in our current program rotate among Boston’s best teaching hospitals: Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Boston Children’s Hospi tal; Massachusetts General Hospital; Shriners

Hospital for Children; and Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. These academic centers cover the breadth of plastic and reconstruc tive surgery, each with its own specific focus. Our diverse faculty provide our residents with a comprehensive exposure to plastic surgery – including breast reconstruction/ microsurgery; pediatric and adult craniofacial surgery; head and neck reconstruction; elective and traumatic hand sur gery; aesthetic surgery; gender-affirming surgery; extremity reconstruction; and peripheral nerve surgery.

Our program has a growing collaboration between our two adult hospitals. In addition to the long tradition of independent chief-resident clinics and chief-resident elective experience, we recently began a yearly research conference where residents showcase their work to an esteemed visiting professor. Residents are also encouraged to attend regional, national and international meetings; many of our residents have present ed and published extensively by the time they graduate. We’ve recently instituted the SIMPL app feedback-system into our program to provide real-time feedback for residents on their case performance, foster mentorship and discussions between faculty and residents, and hone the skills of self-reflection, critique and self-improvement. Our residents pursue myriad fellowships and jobs following training, with the ultimate goal of our program being the creation of excellent plastic surgeons capable of managing a wide spectrum of clinical problems – and who become leaders in academic plastic surgery and further innovation in our incredible field. |

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 15

Kyle Eberlin, MD

Q&A WITH KAVITHA RANGANATHAN, MD

In this installment of Faculty Focus, we present ASPS member Kavitha Ranganathan, MD, assistant professor of Surgery and director of Craniofacial Reconstruction at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Dr. Ranganathan earned her medical degree at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, and completed general surgery and plastic surgery residencies at the University of Michigan Medical School.

Dr. Ranganathan, who completed a fellowship at Johns Hopkins University, has focused her research on increasing access to care in resource-limited environments – and addressing the burden of catastrophic expenditures in lowand middle-income countries.

PSR: HOW DID YOU PREPARE FOR A COMPETITIVE FELLOWSHIP?

Dr. Ranganathan: Challenging yourself to be the best resident you can be is the best preparation for a fellowship. Proving that you are honest, hardworking and patientcentered is of the utmost importance. Because everything is so competitive these days, I would be mistaken in saying that there are no boxes that you must check from a fellowship director’s standpoint – but in my mind, these are secondary to being passionate about what you’re doing. Recognizing what makes you happy and not losing sight of that is important.

PSR: WHAT IMPACT DID THE FELLOWSHIP HAVE ON YOUR CAREER?

Dr. Ranganathan: It improved my ability to teach, as it provided me with opportunities to teach on a completely different level. At my fellowship program, the residents were empowered to do what was best for their education. That environment made me realize that the only way I would get to do a case was if I was teaching it to someone else. This requires a completely different skillset that I’m fortunate I developed prior to my first year as faculty.

PSR: HOW IMPORTANT IS A MENTOR – AND HOW CAN WE FIND ONE?

Dr. Ranganathan: A good mentor is the most critical component of your development on a personal and professional level in plastic surgery. I wouldn’t have matched into plastic surgery without the support of critical mentors in my life. There are a couple of ways to find a good mentor. There are data-driven methods, such as looking up authors in PubMed to see how often they publish and where their trainees are on the author list. If someone puts their trainees as first author on their manuscripts, that’s probably a good mentor. Conversely, if the mentor usually lists themselves as first author, that’s probably not a generous mentor. Another option is to sign-up for team-based mentorship programs such as the ASPS Professional Resource Opportunities in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Education and Leadership (PROPEL) program. These programs increase your exposure to a variety of different mentors and can eventually help you find the right one. To learn more about PROPEL, log-in to plasticsurgery.org, click on “Community” then on “Mentorship Program” under the Directories & Networking category.

PSR: WHAT’S THE MOST IMPORTANT ATTRIBUTE OF A RESIDENT?

Dr. Ranganathan: Being introspective. In order to show up and do better every day, you must be thoughtful about what you do and be critical of yourself.

PSR: HOW DO YOU BALANCE YOUR PROFESSIONAL AND PERSONAL LIVES?

Dr. Ranganathan: Learning to accept chaos is important. Society in general wants us to buy into the notion that everything is picture-perfect, but no one’s life is perfect because perfect doesn’t exist. In my house, dinner means take out, my daughter is always the last one to be picked up from school (hopefully, she will laugh someday about the fact that

16 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Fall 2022

we forgot to pick her up the other day), and laundry is our arch nemesis. That’s OK, though, because at the end of the day we simply celebrate our survival.

PSR: WHAT WAS YOUR GREATEST NON-MEDICAL CHALLENGE OF TRAINING?

Dr. Ranganathan: Leading a group of people is extremely difficult, whether it’s your clinic staff, administrative assistants or residents. Inspiring people to want to work hard and do a good job for you requires a different skillset than the traditional approach of using fear as a motivating factor. Being a “manager” and enacting principles of thoughtful leadership across a variety of levels is the biggest transition I had to acknowledge after becoming faculty. The fact is that you’re responsible for a lot of people. It’s not just about your education anymore, it’s about inspiring a very large group and leading by example.

PSR: HOW WOULD YOU COMPLETE THIS SENTENCE? “I KNEW I WANTED TO BECOME A PLASTIC SURGEON WHEN …”

Dr. Ranganathan: I saw a TRAM flap transformed into a breast, which is crazy since I’m a craniofacial surgeon now. In that moment, I remember thinking: “Wow, I think I could love every part of this field.”

PSR: WHAT ARE SOME OF THE CHALLENGES OF BEING A PARENT AND A PLASTIC SURGEON?

Dr. Ranganathan: Being a good surgeon makes you a better mom. And being a good mom made me a better surgeon. The

skill set required to balance the variety of responsibilities of a surgeon and parent are very similar. The only time I’m truly 100 percent living in the moment is when I’m in the O.R. – or when I’m home with my daughter. It’s important to remember that you don’t have to choose. It’s possible to do both.

PSR: DESCRIBE YOUR EXPERIENCE THROUGH RESIDENCY AND AS AN ATTENDING AS A FEMALE PLASTIC SURGEON.

Dr. Ranganathan: No matter who you are, but especially if you are from certain backgrounds, you must consistently demonstrate excellence, from the minute you walk in the door. People are always judging, whether we like to admit it or not. Every minute of residency is your time to demonstrate excellence and to build yourself into the best surgeon you can be. It doesn’t mean you won’t make mistakes. But always try your best, and over time you’ll be able to distinguish what you value from what others tell you to value.

PSR: WHAT ADVICE DO YOU HAVE FOR PLASTIC SURGERY RESIDENTS?

Dr. Ranganathan: If you feel as though you don’t fit into the world of plastic surgery, plastic surgery needs you even more. When I entered the field, I knew I did not fit in – or, at least, I felt like I didn’t fit in. I’ve recently realized this is far from the truth. Our patients, trainees and the plastic surgery specialty as a whole need people who are different. |

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 17

This Q&A was facilitated by Vishwanath Chegireddy, MD, PGY-6 in the Harvard Plastic Surgery Residency Program, Boston.

By Kimberly Khouri Baddoura, MD, & Charles D. Hwang, MD

Boston

Welcome to Boston, the capital of Massachusetts and home to many American historical sites. It’s also a breathtaking, waterfront quintessential New England city. You can walk most of Boston, but the city also offers public transportation and a plethora of ride-sharing services that make this city accessible.

The Convention Center, home of Plastic Surgery The Meeting 2022, is in the heart of the Seaport District, the fastestgrowing and newest neighborhood in Boston. The Seaport District is part of the Port of Boston Harbor and home to The Seaport Hotel & World Trade Center, Institute of Contemporary Art and Boston Children’s Museum, as well as the John Joseph Moakley United States Courthouse. This waterfront neighborhood is bustling with history, new restaurants and shops. Stroll along the Boston Harborwalk and spend time outdoors at Fan Pier, a beautifully landscaped green space right along the water that offers tables and benches, a lookout terrace and fire pits. This public walkway spans 43 miles, connects Boston’s waterfront neighborhoods and encompasses most of Seaport’s unique shops, public art and museums. If

you want an interactive living history experience, walk to the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museums, where you can learn about the seminal events that altered American history – and even board a ship and throw British Tea into the Harbor.

After a day of exploring, take time to enjoy the fresh food and hip cocktails that Seaport District is known for. The neighborhood has significantly changed in recent years, but the Barking Crab has stood the test of time. This boisterous, low-key seafood restaurant opened its famous red-and-yellow-striped tent in 1994 and has been serving fresh clambakes, lobster rolls and oysters with

shells that you can chuck into the harbor. A newer (and highly regarded) dining option in Seaport is Nautilus, a Japanese seafood fusion restaurant known for tapas-style plates, sleek interior design and variety of sake options. Although we don’t usually recommend chain restaurants while exploring a new city, the flagship Legal Seafood Restaurant is also worth a visit. This three-story building sits directly on the water, has a spectacular roof deck and each floor has a specific and curated menu. A few notable places for enjoying a drink in the Seaport District include Envoy Rooftop, Trillium Brewing, Menton, Row 34, Sportello, Coquette and Lolita Fort Point.

18 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Fall 2022

We also recommend visiting the Beacon Hill neighborhood, a time capsule of old New England that has cobblestone streets, red brick homes and quaint streetlamps. The quintessential neighbored houses the state capital building, is adjacent to the Boston Commons Garden and Park and has cozy cafes, local boutique shops and restaurants. Grab a coffee or an ice cream at JP Licks off Charles Street and get lost in the charming and narrow streets of Beacon Hill. Make sure to snap a photo while on Acorn Street, as it’s the mostphotographed street in the United States. Another great neighborhood to visit is Back Bay. Walk down Newbury Street, where you’ll find retail shopping, dozens of new restaurants and prime peoplewatching opportunities.

The Boston Public Library is a great spot to spend time in the walls and halls of a regal historic building. While in Back Bay, also visit the Prudential Center, eat at Eataly and marvel over the views in the Skywalk Observatory at the top of the “Pru” (Prudential Tower). Other great neighborhoods to explore include the North End, Boston’s Little Italy, South End and Fenway Park – home of the Boston Red Sox. If time permits, head to Cambridge and visit Harvard Square, explore MIT’s campus and walk the esplanade overlooking the Charles River. If the weather permits, you can even rent a sailboat or kayak.

New England also offers plenty of opportunities for sports fans. Depending upon the season, you can catch the Red Sox, the NBA’s Boston Celtics or the NHL’s Boston Bruins. (The NFL’s New England Patriots actually play in Foxborough, Mass.) A plethora of sports bars also can make you feel like you’re at the games without purchasing a ticket (Bleacher Bar is a personal favorite).

24 hours is not enough time to see all of what Boston has to offer. However, below are highlights of what we feel are the Top 5 restaurants, bars and things to do. |

Dr. Baddoura is PGY-4, and Dr. Hwang is PGY-3, in the Mass General Brigham Harvard Plastic Surgery Residency Program.

BEST BETS IN BOSTON

Residents from Harvard Mass General Brigham provide their recommendations for areas to visit, places to dine and things to do around town.

TOP 5 NEIGHBORHOODS

Seaport

Beacon Hill

Back Bay

North End

South End

TOP 5 RESTAURANTS

Salty Girl (Seafood)

Neptune Oyster (Seafood)

SRV (Italian)

Arya Trattoria (Italian)

Menton (French/Italian)

TOP 5 BARS

Lookout Rooftop Bar

Beehive (live music on weekends)

Lounge Bar

Hill

TOP 5 MUST-DO ACTIVITIES

Relaxing after a challenging day of training at Mass General Brigham Harvard Plastic Surgery are (from left) Charles Hwang, MD, PGY-3; Seamus Caragher, MS-4; Eric Wenzinger, MD, PGY-5; Ian McCulloch, MD, MS, PGY-3; Amy Colwell, MD; Jason Gardenier, MD (immediate-past chief resident); and Kimberly Khouri Baddoura, MD, PGY-4.

Participate in a historic tour/ visit a museum

Eat a lobster roll and/or clam chowder

Watch a Boston sporting match

Stroll the Esplanade/Boston Commons

Visit Harvard/MIT or one of the 100-plus colleges in Boston

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

1. Envoy

2. Yvonne’s 3. The

4. Oak

5. 1928 Beacon

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

SOLUTIONS, RESIDENTS AND THE FUTURE

Q&A with The PSF President Bernard T. Lee, MD, MBA, MPH

Bernard T. Lee, MD, MBA, MPH

Bernard T. Lee, MD, MBA, MPH

Ahead of Plastic Surgery The Meeting 2022 in Boston, the Plastic Surgery Resident Editorial Board collaborated on a set of questions for The PSF President Bernard T. Lee, MD, MBA, MPH, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Division chief, which has been designed to gain his insight on leadership, the opportunities The Foundation holds for residents and its work for the specialty’s future.

PSR: As The PSF president, what challenges have you experienced when leading people – and how did you overcome those challenges?

Dr. Lee: Prioritization when leading people and teams. We have many enthusiastic members who have great ideas – but, unfortunately, we’re limited by time and resources. For example, as all meetings were cancelled during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, our leadership team was presented with a lot of potential strategies for member engagement. Ultimately, we chose a Virtual Grand Rounds format led by Angela Cheng, MD, which was an extremely popular and successful program. This took much effort and planning, but the reason we prioritized this initiative was that it aligned with an organizational mission: to educate ASPS members.

PSR: With The PSF in mind, what key tips do you have for keeping your staff motivated, and what are some plastic surgery improvement programs that are increasing The Foundation’s international reach?

Dr. Lee: Staff motivation is becoming increasingly important, especially with the new model of remote/hybrid work environments. As we focus more on project-based work vs. logging hours in the office, it’s crucial that we respect the line between work and personal time. As for plastic surgery improvement programs, I want to highlight the registry programs – which are now consolidated under the Plastic Surgery Registries Network (PSRN). In terms of international programs, we have Surgeons in Humanitarian Alliance for Reconstruction, Research and Education (SHARE), which recently completed its inaugural, two-year virtual-educational program that mentored surgeons in sub-Saharan Africa.

PSR: What are your thoughts on the future of academic plastic surgery?

Dr. Lee: It’s an exciting time to embark on a career in academic plastic surgery. We have so many talented surgeons working on the most complicated problems in our field. Whether your area of focus is research, education or clinical excellence, there’s a place for new ideas and energy. For example, at the time of my residency training, there were very few surgeons even thinking about lymphatic surgery, vascularized composite allotransplantation or peripheral nerve surgery. My area of research on near-infrared imaging and tissue perfusion didn’t even exist; now these devices are common in O.R.s and even built into many microscopes.

PSR: What role do you envision The PSF will have in the future of academic plastic surgery?

Dr. Lee: The role of The Foundation is to support the research and international activities of ASPS. As academic plastic surgeons continue to develop novel research ideas, the organization will be there to support these investigators. There are so many avenues for research funding – including pilot grants, innovation grants, diversity and inclusion grants, National Endowment for Plastic Surgery grants and research fellowships. In addition, our role is to identify specific areas of research with high visibility, such as breast-implant safety.

PSR: What are the major contributions of The PSF to plastic surgery residency/residents?

Dr. Lee: When I was the ASPS/PSF Board Vice President of Academic Affairs, we consolidated resident education and programming under The PSF. This allowed for alignment across a wide variety of areas within the organization, including Resident Boot Camp, Senior Resident’s Day, Residents Council, Resident Curriculum Development and the Resident Education Center. Bruce Mast, MD, is the current board vice president and has been instrumental in continuing to develop all these important programs to support our trainees. When it comes to research, we have a listing of the past 10 years of funded investigators and when look at the names, many of these surgeons are now successful academic surgeons who first received funding from The PSF.

PSR: What are the ways a resident can be involved in The PSF?

Dr. Lee: Just ask! There are many committees in which a resident can be involved. The first place to start is the Resident Council, as a listing exists of all the areas one can volunteer across both ASPS and The PSF. |

20 Plastic Surgery Resid ent | Fall 2022

EDITOR’S NOTE : “Dear Abbe” – named in honor of plastic surgery pioneer Robert Abbe, MD – provides plastic surgery residents an opportunity to anonymously share concerns and seek advice from a highly respected, senior-level faculty member. Christian Vercler, MD, a clinical associate professor in the Section of Plastic Surgery at the University of Michigan – where he also serves as co-chief of the Clinical Ethics Service of the Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences – steps into Dr. Abbe’s shoes for this installment. The views expressed in this column are those of the author and should not be considered legal advice. Residents and Fellows are encouraged to submit questions to DearAbbe@plasticsurgery.org. Names will be withheld.

Seek support when dealing with your negative outcome Abbe DEAR

Robert Abbe, MD

Dear Abbe:

Dear Abbe:

How do you stay positive after facing a bad outcome relating to the surgical procedure of a patient you’ve treated? What are ways to cope with the feelings of hopelessness and a lack of support during those periods?

– Helplessly Hopeless

Dear Troubled:

Nothing is as devastating as when one of our patients has a complication. There’s no way to deny the fact that something we did harmed the patient. As the sociologist Charles Bosk noted in his classic study of surgical education, “When the patient of an internist dies his colleagues ask, ‘What happened?’ But when the patient of a surgeon dies his colleagues ask, ‘What did you do?’ ”1

The unbreakable connection between our professional technical performance and the patient’s outcome is the source of our greatest satisfaction and pride when things go well – but also our lowest lows when things go poorly, despite our best efforts. The feelings that we have when our patient has a complication are a normal part of any surgeon’s life. Not experiencing these negative feelings is a sure sign of psychopathology – and we should guard against developing a “detachment” that might insulate us from feeling responsible and appropriately remorseful when we cause unwarranted suffering in a patient.

Luu, et al.2, studied surgeons’ responses to adverse events and identified four phases that every surgeon in the study experienced: the kick, the fall, the recovery and the long-term impact. The kick refers to the intense feelings of failure and physiological response we experience as a result of the event. The fall that follows closely is the feeling of chaos and spiraling out of control. The recovery occurs over time and through talking about the event with colleagues, and through focusing on “what can I learn from this?” The long-term impact varies among individuals. This study established that these feelings and experiences are common among surgeons – and, importantly, that most surgeons found that talking to colleagues proved to be a main source of support and coping.

The great German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche has several aphorisms which are quite apt to the life of a surgeon. The most well-known is: “That which does not kill me makes me stronger.” Another relevant answer to this question is: “If we possess our why of life, we can put up with almost any how.”3 That second concept was further popularized by Viktor Frankl in his book Man’s Search for Meaning, 4 which chronicled his perseverance as a prisoner for three years in four Nazi concentration camps. One way to combat these feelings of hopelessness is to reflect on your why. Having an inchoate sense of purpose will compound any feelings of dread that you have. You need a sense of purpose beyond the narcissistic projection of “the perfect surgeon” that we all strive to be – but of which we often fall short.

I personally find studying the lives of other surgeons helpful. Harold Gillies, MD; D. Ralph Millard, MD; and Joseph Murray, MD; did not lead perfect, uncomplicated lives. I take solace in seeing myself as part of this inherently flawed human enterprise of boldly intervening in our patients’ lives and promising to be there for their surgical problems – and knowing that I’m not in this alone. |

REFERENCES

Forgive and Remember: Managing Medical Failure. 2nd ed. 2003. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

2. Luu S, Patel P, St-Martin L, et al. Waking up the next morning: surgeons’ emotional reactions to adverse events. Medical Education. 2012. 46: 1179-1188.

3. Twilight of the Idols. 1899.

4. 1946

1.

Plastic Surgery Resident | Fall 2022 21

LIPOSUCTION

By Michael Hu, MD, MPH, MS; Anjali Raghuram, MD; & Jeffrey Gusenoff, MD

• Distribution of fat

• Skin evaluation, including wrinkles, laxity, surface irregularities, dimpling and scars2

PROCEDURE

Tumescent

Liposuction is one of the most common cosmetic surgi cal procedure in the United States. In 2020, more than 200,000 patients underwent liposuction.1 Although the number of procedures performed has dropped signifi cantly over the past two decades, it remains highly popular and is often a step in autologous fat-grafting and adipose-derived stem cell harvesting. As such, all plastic surgeons should be well-versed in the background, classifications and techniques of liposuction. Conse quently, this topic is frequently tested on the In-Service Examina tion – and review is high-yield. The following is a summarization of important concepts regarding liposuction, covering areas recently tested on the yearly examination.

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

Similar to all elective procedures, a thorough assessment of the physical condition of the patient must be performed. Plastic surgeons should perform a complete history and physical examination, includ ing the following:

• Prior liposuction procedures

• Comorbid conditions

• History of blood-clotting problems

• Conditions that may increase risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

• Medications, particularly those that may affect wound healing and blood clotting