Usually, when we talk about migrants and refugees coming to the UK, we talk about how our call to share Christ cross-culturally now not only applies to the four corners of the globe but also to the four corners of our front gardens! However, in the midst of talking about mission on our doorstep, we rarely, if ever, talk about the missionaries on our doorstep - our brothers and sisters in Christ who have come from other countries, bringing their unique Christian faith and their own missionary zeal to the cities and towns of our increasingly secularising British Isles.

This super-sized edition of Reach unites three themes regarding these brothers and sisters: welcoming diaspora peoples into British churches, partnering with diaspora churches and Christians, and mobilising diaspora peoples for gospel ministry both in the UK and worldwide. Pioneers UK’s long historical relationship with Africa means that this Reach is weighted quite heavily toward African diaspora peoples, but the principles of welcoming, partnering and mobilising certainly apply to our brothers and sisters who make up the European, Middle Eastern and Asian diasporas (South, East, Central and Southeast!) and any of the dozens of other diaspora groups in the UK. We’d need a few more editions of Reach to give them all the attention they deserve!

Lots of people who know a lot more than me have graciously shared their expertise for this Reach, and I’m particularly indebted to my friend and colleague, Harriet Ngugi, who has co-edited this edition with me. She has provided much wisdom and guidance as I’ve tried to tackle a subject that was certainly beyond me. My sincere hope is that what you read in the following pages will spark conversations, encourage action and catalyse change in our churches. To that end, I’d love to hear your thoughts on this edition and on this subject. Get in touch, if you fancy, at amanda@pioneers-uk.org. Until then...

I first heard the word ‘diaspora’ in a History of Christianity course, referring to the spread of Jewish Christians throughout the Roman Empire in the first few centuries AD. To be perfectly honest, I had read the word several times before I heard it, and thought it was pronounced ‘dia-SPOR-a’, conjuring the image of a fungus shooting its spores into the air and relying on the wind to carry them to places near and far so that the fungus could grow and multiply in other places. Obviously, I didn’t consider first century diaspora Christians to be a fungus. Quite the opposite. But the mental picture was helpful nonetheless.

maybe they land in a sunflower field where they blend in, living side-by-side with indigenous flowers of a different kind. Wherever they’ve landed, these seeds and the flowers they produce make up the dandelion diaspora.

Even though I now know that it’s pronounced ‘di-AS-pora’, when trying to define the diaspora, the image of spores or seeds being hurled into the great unknown still sticks with me. Perhaps we can think of the diaspora like a dandelion. The dandelion grows and multiplies quite happily in its own little patch of grass, probably surrounded by hundreds of other dandelions. Then one day things change. Its petals turn into seeds and the wind catches them. They whirl up into the air, carried by the wind. Eventually they land - sometimes in the same little patch of grass, and sometimes very far away, They have the same genetic code they’ve always had, but they’ve settled somewhere new.

As I learned in my History of Christianity course, the reality of diaspora is nothing new, and we are certainly not unfamiliar with diaspora peoples in the UK. As a nation that has welcomed migrants and refugees for a long time, nearly all of us know, or live near, someone who was born in a country outside the UK. And without doubt, we all know someone whose parents or grandparents were born outside the UK.

Perhaps they land amongst other dandelions, where every flower is the same kind. Or maybe they land in a field full of wildflowers, where every flower is a different species. Or

There is scarcely a country in the world that is not host to a diaspora of some description. Whether it’s Australians in Brazil or Bangladeshis in Thailand, diaspora peoples are everywhere. But why? Many of us could never imagine leaving home and family and familiarity to go to a completely new place to live amongst strangers with different habits and beliefs. But people leave home for all sorts of reasons. Many leave their home country for economic reasons - perhaps it’s no longer possible to earn a living or support a family in their home country. Others leave for educational reasons - to access prestigious or specialised educational institutions. A few might leave because of a sense of adventure or restlessness. Some leave to further their career or to follow a spouse. Still others are forced to flee, as refugees from war, poverty, famine or

disease. And in the worst moments of humanity’s story, some leave home unwillingly as slaves.

In Britain, some diaspora groups are bigger and more evident than others. According to the Office for National Statistics (www. ons.gov.uk), in 2020 the largest diaspora group (by country of birth, as opposed to ethnicity) was India, with 847,000 Indianborn British residents. Next came Poland (746,000), Pakistan (519,000) and Romania (370,000). The statistics highlight the top 60 birth nations (Japan is number 60, with 30,000 people in its UK diaspora), then groups the smaller diaspora groups as Other, which comes in at a massive 1,085,000. We are a rainbow nation on a scale we’ve never known before!

dimension, though, when we begin to dig down into the data and realise that hundreds of thousands of them have come to the United Kingdom from Christian nations and have not only been quietly multiplying in numbers as people, but have also been quietly multiplying in numbers as vibrant, dedicated, missional brothers and sisters in Christ, many of whom have a driving passion to see the United Kingdom re-won for Christ on an epic scale.

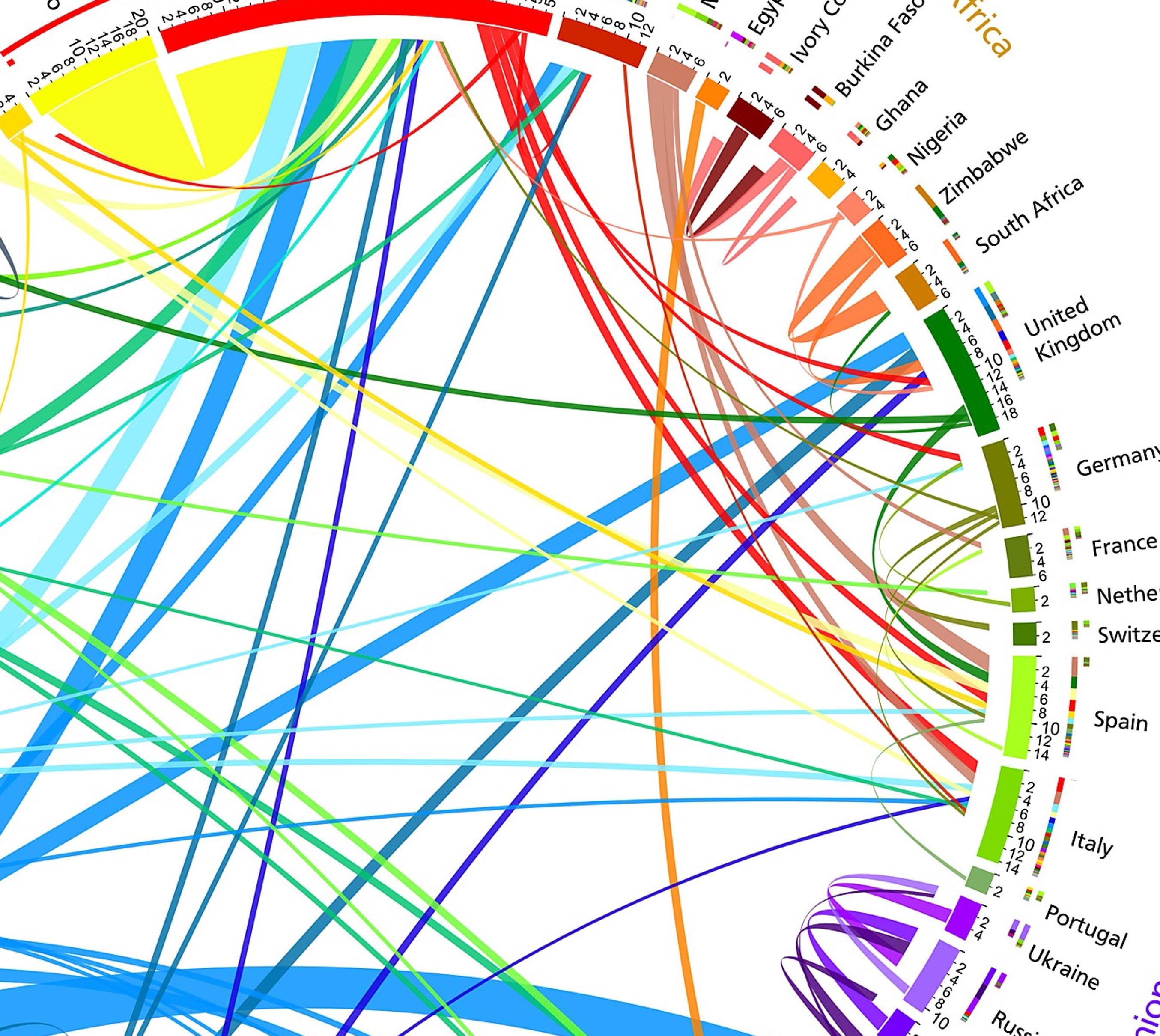

So where are these diaspora peoples located? I recently had a conversation with Ian Prescott, for whom I’m indebted for almost all the statistics and graphs I present in this article. Ian and his wife Anne-Marie served in East Asia for 30+ years, and are now partnered with Global Connections as ‘Catalysts for Diaspora Ministries’. Ian explained to me that nearly every diaspora group in the UK follows a similar pattern: there is a concentration of people in London, and then another concentration somewhere else in the UK. London is by far the most diverse place in our nation. We can think of London like our wildflower field. Hundreds of nationalities have converged in London and are living side-by-side, creating a tapestry of culture and worldview and religion. Other major cities and towns may be home to the secondary concentration from any given group: whether it’s Ivorians in Norwich or Thais in Gloucester, these may be more akin to our dandelions in the sunflower field, living amongst the indigenous population. Rural or remote areas see fewer, if any, concentrations of diaspora peoples, but they will certainly be living here and there, blooming where they are planted.

Whether it’s the Chinese Overseas Christian Mission, who have a huge presence in Britain, or the Nigerian Redeemed Christian Church of God, who’ve planted over 900 churches in the UK in the last 30 years, or one of the hundreds of small-but-growing diaspora churches peppered throughout our cities, towns and villages, the diaspora church is on the move. Like never before, we have the opportunity - both as indigenous British churches and diaspora churches - to feel our way, together, toward becoming the ‘big-C’ Church.

Changes and adjustments will need to be made, of course. Grace and cultural understanding will need to be extended, and differences will need to be embraced and celebrated, but - WOW! What a glorious privilege to be part of this new and exciting work of God. The global church of Christ has arrived on our doorstep alongside hundreds of thousands of the unreached. And now we get to join hands and call the unreached to Jesus. Let’s do it together.

Diaspora peoples are living in every corner of the UK to varying degrees. This fact takes on a new and exciting

Abel & Sander (2014). Quantifying Global International Migration Flows. Science, 343 (6178) For an interactive version, go to http://download.gsb.bund.de/BIB/global_flow

This graph is a stunning representation of global migration patterns between 2005-2010. It represents the number of people (by 100,000s) migrating between any two given countries during this time. The graph is by no means exhaustive, but it provides a strong visual for the massive scale of migration in our modern era.

Emmanuel Bishopston is a Church of England church plant which was established in North Bristol in January 2012. It is situated in an affluent part of the city and pre Covid, about 80 adults and 40 children attended its weekly Sunday services. Historically, most of the church family have been white, university-educated people from the UK. Those from a different culture or background often felt aware of their difference. We really wanted this to change. We wanted to reflect the diversity of God’s people more fully and not be monochrome. We feared we might be inadvertently doing things that were a turn off to people from other nationalities and cultures. We didn’t have huge resources to pioneer new initiatives but our uniformity unsettled the leadership of the church. We weren’t exactly sure what we could do to address it but we knew we needed to do something!

When we looked more closely at the Bristol Ward Data, we learnt that 82 per cent of the Bishopston and Ashley Down ward are White British, but 10.6 per cent are Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic. The ward has a mixture of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Turkish, Somalian, Chinese, Black African and Black Caribbean people and this certainly wasn’t reflected in our church family in 2020.

provided rich food for thought and everyone was struck by how many different aspects there are to being an intercultural church.

Over the course of a few months, the team did the following things:

Martha* (not her real name), a member of the congregation from a different ethnic background, explains: “North Bristol is made up of lots of people from other cultures and faiths – I love eating Turkish food locally, sharing jokes at work with nurses from the Caribbean, and having friends from Romania, Italy, and Pakistan. However, our church – although a loving family and seeking to know Jesus well, doesn’t reflect this breadth. I was struck by the vision of the church in Revelation: “After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb.” I longed for our little church to be more like the heavenly bride of Christ.”

We decided it was time to take action.

In 2020, a small team gathered to chat and pray about the lack of diversity in the church family. They established an “Intercultural Working Group” made up of people who either worked alongside minority groups in Bristol, were from overseas themselves or had a heart for internationals. They began brainstorming small steps that could be taken to signal to any visitors that they were welcome, even if they didn’t, at an initial glance see people like themselves in the church family.

1) A kids’ photo challenge– we encouraged the families of the church to walk up and down the high street and spot flags or restaurants from other countries. We knew there were so many different cultures and nationalities represented locally and we wanted families to begin to see the world on our doorstep. We challenged them to find out more and pray for Christians in some of these countries.

2) Translated the word for “Welcome” into four different languages and ensured they were permanently at the top of our church service sheet. While this is a tiny touch, people often comment on it and it signals something important in terms of our hopes and expectations about who might visit each week.

A member of the congregation attended a training course on intercultural mission, organised by SIM. He then shared the teaching with the working group and the elders. The course

We wanted to reflect the diversity of God’s people.

We became aware of the fact that thousands of Hong Kong citizens were due to move to the UK because of the political situation in Hong Kong. Our elders suggested we consider becoming a “Hong Kong ready” church. This was an idea promoted by Dr Krish Kandiah, the founder of adoption charity Home for Good. He challenged churches to consider how they could meet the practical, spiritual and emotional needs of the hundreds of thousands of people expected to move. At this point, we didn’t know of anyone coming to Bristol from Hong Kong and it seemed hypothetical but we talked and prayed at our monthly church prayer meeting about being ready. We also signed up to the website to signal that we were ready to welcome anyone from Hong Kong.

initial families began inviting other local families to Emmanuel Bishopston and now we have more than 20 adults and children from Hong Kong worshipping with us regularly.

The arrival of these families has been wonderful and such an answer to prayer. While we could say it is was a result of our strategy to reach internationals, it doesn’t really feel like that. Rather, it feels like a miracle and simply God’s kindness to us. We wanted to reflect the beautiful variety of the bride of Christ, we prayed a bit and we thought a bit but in reality, it was God who brought these lovely people to us and they chose to stay. We didn’t really do anything special or right but perhaps, even the act of talking about “being Hong Kong ready’ prepared us for when people began to arrive.

Of course, welcoming people from Hong Kong is just the first step in helping them settle into a new city, country and church. There are so many challenges related to leaving your home country – most families are trying to find jobs and schools and buy houses whilst navigating all the cultural differences and funny habits of English people! We are just at the beginning of learning how to help people settle in.

Then in September 2021, two families from Hong Kong appeared at church one Sunday. We don’t know how they heard of Emmanuel Bishopston or why they settled but they did! Despite saying we wanted to be “Hong Kong ready,” it was quite surprising when families actually started visiting. The two

Some of the things we are currently doing include emailing a draft of the sermon in advance so people can follow along more easily; asking people to read, pray, share their testimony, serve at communion; elders chatting regularly with newcomers to find out how things are going and if there is anything we can do differently or to help; moving at the pace of each family – some have wanted to join Bible study groups immediately or get involved serving tea and coffee at our toddler group, others have preferred to just watch and listen before getting more involved. On Maundy Thursday, a group from Hong Kong offered to organise a Taizé service for us. This is something we have never done before and while it is not mainstream in Hong Kong either, they thought it could be something they could lead and we could enjoy together as it is accessible for all. It was a special evening for those who gathered!

What was once a predominantly white, English, middle class church has changed beyond recognition.

The funny thing is, that as well as gaining 20+ people from Hong Kong, we have also grown in diversity in other ways. Since resuming normal church services in the Autumn 2021, we have experienced significant growth and in particular have seen older people and people from other countries settling with us. What was once a predominantly white, English, middle class church has changed beyond recognition.

In a recent kids’ talk upfront, the speaker asked everyone who wasn’t “from England” to stand up and it was remarkable to see about a third of the room stand up. People from Hong Kong, Pakistan, Germany, Australia, Romania, Northern Ireland, Wales, Czech Republic, Thailand, China and Kenya are all now represented in our church family.

Claire Walford works part-time as a communications consultant for The Clewer Initiative, the Church of England’s modern slavery response. She is married to the pastor of Emmanuel Bishopston and has three children (aged 14, 11 and 7) and a gorgeous cockapoo called Hetty!

It’s easy to get involved in welcoming migrants and refugees into our churches, neighbourhoods and homes. Opportunities for showing the love and hospitality of Christ to the ‘strangers and aliens’ amongst us have never been more abundant. These websites and articles will help you on your way.

It seems that God prompted us, back in 2020, to start praying and thinking about our lack of diversity and over the last couple of years, He has answered our prayers and brought new people to us. Of course, there is a natural momentum to the situation. Once one family sees another family who look like them, it inevitably makes them feel welcome and at home. We can’t wait to see how God builds His church over the next few years. afghanwelcome.org welcomechurches.org

I was a Stranger: a list of helpful websites - pioneers-uk.org/2022/01/i-was-a-stranger How to be ‘Hong Kong Ready’ - welcomechurches.org/updates/hong-kong-ready-churches

Ebenezer Aryee joined the Pioneers UK board in 2019 just as we were starting to think seriously about what it would mean to engage in a meaningful way with the thousands of Afro-Diaspora Christians who have settled in British cities and towns in the past couple of decades. As a mission with a long history of focus on Africa, we are very aware that African churches and missions have begun to engage in ‘reverse mission’ - sending their own missionaries to the (now) largely secular European nations that sent missionaries to Africa in the 19th and 20th centuries. Ebenezer, along with others who feature in this edition of Reach, has helped steer us toward the reality of becoming a sending gateway not only for indigenous British Christians, but for diaspora Christians of all backgrounds, too.

Our editor, Amanda, sat down with Ebenezer in the summer to pick his brain about his own experience as a diaspora pastor in the UK and about the vision of the Afro-Diaspora Mission Network (ADMiN).

Amanda: Thank you so much for being willing to sit down with me today, Ebenezer. I’m looking forward to finding out about you and ADMiN, but why don’t we start with you?

Ebenezer: I was born in Ghana and grew up in Accra, the capital of Ghana. I was born into a Christian home and grew up in the Presbyterian Church. When I got into my teens, I went to a boys’ boarding school in Ghana, and by the time I was 16 I wasn’t really seriously going to church. Then I went to uni in the Soviet Union, and when I finished my studies I came to the UK. It was in the UK that I really came back to the Lord.

In 2009, we started offering the Kairos Course here in Leeds, then in Bradford, in Newcastle… and by 2011, we were planning to take the Kairos Course to Ghana, Nigeria and The Gambia. We had a five-man team – two indigenous English people, myself, one Nigerian and a Ghanaian who was based in Brazil. Then in 2014 I was then invited to be part of the Kairos International Leadership Team, and I was appointed to coordinate bringing Kairos to new nations.

In 2005, a friend of ours was planting a startup fellowship which later became a church plant. I was involved in that, but then by 2007, we were being challenged about the fact that the fellowship that we were involved in was only using the Ghanaian language. A few people came to the church but they didn’t speak the predominant Ghanaian language - they were Ghanaians, but they didn’t really fit in because we didn’t speak their language. They could understand us, but it wasn’t their mother tongue. So I realised that there was a bit of a limitation because of the language that we were using. So we got together to talk about that and discuss and pray and ask ourselves what we could do to reach people who don’t speak the Ghanaian language. So the plan was made to start another fellowship - a Ghanaian fellowship, but using the English language so that all people could be part of it. That was in 2007.

During this time I was also attending Mattersey Assemblies of God Bible College, doing an MA in Missional Leadership. I completed that in 2013 and, after my pastor challenged me to go for ministerial training, I was ordained as a pastor in 2017.

Then in 2009, I did the Kairos Course. And that turned my whole life upside down in terms of mission and being passionate about the mission of God and being involved in mission - especially mission mobilisation. Through the Kairos Course, I came to see that my calling was to become a mobiliser, calling all God’s people to be on mission with God. I sort of view myself as somebody blowing the trumpet, calling every believer to be part of the mission of God.

Amanda: You’re the founder of the Afro-Diaspora Mission Network. Can you tell me how ADMiN came about?

Ebenezer: So ADMiN came about when I saw the state of the diaspora churches in the UK. There were a lot of Africaninitiated churches all over the UK, growing and springing up all over the place, but there was a limitation in the sense that most of the churches were just one nationality - a Ghanaian church, a Nigerian church, a Kenyan church, a Zimbabwean church,

“I came to see that my calling was to become a mobiliser, calling all God’s people to be on mission with God.”

that kind of thing. And what we saw was that they were not actively reaching out to the host community, the indigenous people, or even other cultures. So that, along with the fact that Kairos places a lot of emphasis on cross-cultural mission, really began to challenge me. So, I began to have conversations with some church leaders here in Leeds, especially those who had done Kairos, and began to ask, “What can we do about this situation? We can’t just have all these churches everywhere. That is not the whole mission of God. The whole mission of God is to reach all nations.”

So in September 2015, we held a consultation in Leeds. About 12 leaders came, and we had a resource person come in from my Bible college to facilitate our discussion. It was so good. People were really enthusiastic, saying, “How can we be equipped to do cross-cultural mission? We can’t just sit here and say we have come to do God’s work but then only reach out to our own people.”

So in 2016, we decided to have another gathering. And from 12 in 2015, this time it was 34 and from 34 to 70. So by 2019, our gathering in Birmingham was about 120 people. So we said, “Let’s have a network with people who have attended. Let’s keep ourselves connected.” And so that’s how ADMiN was born - from being challenged about how to help equip and inspire diaspora churches to be fully missional, to engage cross-culturally and reach out to their host community and other cultures.

ministry is mission mobilisation. We have as our mission what we call the Three Dimensions of Glocal Mission Mobilisation. (It’s ‘glocal’ - both local and global.) The first level is bringing mission awareness. What we find is that because of the way most diaspora Christians initially came to the UK, mission is not a primary thing. About 80% of diaspora people have come because of economic reasons; a few have come because of educational pursuits, or career; others have come as refugees, all kinds of reasons. Mission was not the primary thing that brought people across to the UK.

Amanda: So you’re getting together with all of these ministers, diaspora ministers, from all around the UK, and talking about what you can do to help the church become more fully missional. What are some of the strategies that you’ve come up with to try and accomplish this?

Ebenezer: Yes, what we really want to see is diaspora churches becoming missional communities. As a network, our underlying

So those who are Christians want to find a place to belong – a place to worship and serve God, but mission is not central to what they do. To get people to think differently, we need to bring awareness - for them to understand that irrespective of how they got here, there’s a God purpose in it. And that God purpose is for us to become his missionary people, to become ambassadors of Christ, whilst we are in a foreign land. So our first dimension is to bring mission awareness, and the Kairos Course plays a significant role in that.

After people discover what the whole mission of God is about and feel passionate about being involved in one way or the other,

most people then need equipping to be able to be effective. If people feel called to reach out to Muslims, for instance, how do they get the skills and the knowledge to be able to do that? So the next level of our mobilisation is to equip people, starting with the leaders of the church. If the churches are going to be transformed and evolve into missional churches, we need to equip the leaders. How do you become an effective leader of a multicultural church? Because if one day you’ve come to the point that other cultures are coming to your church, how will the leadership be able to adapt the style or other things to be effective? So we have leadership development for church leaders, to help them to transition and to be equipped and be skilled and competent in leading and growing multicultural churches. So that is the second level of mobilisation for us - the equipping part.

a taxi driver, as you are driving people, you’re a missionary to them. We empower people. We help them build confidence in reaching out, intentionally, in whatever sphere God has. So that is the local aspect of the mission that we talk about.

But it is also global. For the diaspora, especially the firstgeneration diaspora, for maybe 95% of us, we have already arrived at our mission field, because we’ve already made the journey to pack our bags and go somewhere else.

And then the third level is actually getting people fruitfully engaged, hands on, involved. And how do we help people to do that? One way is that we talk about the ministry of all believers, and we let people know that wherever you are, whatever sphere of life God has placed you in, it’s an opportunity for you to bring the Gospel to that environment. So you are a missionary. If you are a nurse, you are a missionary in the hospital; if you are a teacher, you are a missionary in the school; if you are

We want people to see that wherever they are there’s an opportunity for them to share the gospel. Part of ADMiN’s work is to affirm people and encourage them that although they may not carry the professional tag of a missionary, they’re still doing the work of a missionary. And for the second and third generation diaspora, especially young professionals, we are really encouraging them to see how God can use them, maybe even away from the UK. So we support them, we affirm them we endorse them to do the work as God calls them and opens the door for them. This is how we get people to be going on the mission of God.

Amanda: Thank you so much for this, Ebenezer! It’s been really eye-opening and inspiring to see how you and ADMiN are pioneering the growth of mission amongst the diaspora in the UK. There’s a lot more to say, so I think we may call this ‘Part One’ and direct our readers to the second part of our chat, which is all about your thoughts on how diaspora churches and indigenous British churches can come together in meaningful gospel partnership. I look forward to hearing more!

For more of our interview with Ebenezer, see p 32.

We want people to see that wherever they are there’s an opportunity for them to share the gospel.

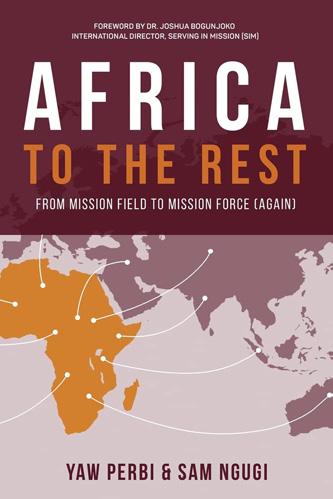

BY HARRIET NGUGI

BY HARRIET NGUGI

The UK has perhaps one of the most multi-ethnic church contexts in the globe. Peoples from virtually every part of the globe converge on this small island, bringing with them a rich diversity of cultures, experiences and blessings, as well as dynamic challenges due to intense cross-cultural and inter-ethnic interactions. The biblical principle of ‘one Kingdom’ and ‘one Body’ envisages both unity and diversity among Christians. Aspiring for unity as a biblical imperative is one thing, but the practicality of it can be daunting and often challenging.

When my husband and I relocated to the UK with our two children, we were received by family friends who have served with my husband. On Sunday morning we joined the family for a worship service in their church in a city in the north of England. We were immediately recognised as visitors and heartily welcomed by everyone. Our boys were immediately and naturally included in play before the service began. The service itself was vibrant and lively with worship songs sung in both English and an African language, from which the majority of the

members came. Later in the week the pastor and his wife visited us at our hosts’ home, gave us some tips for settling in the UK from Africa and also prayed for us. This was our first encounter with the African diaspora church in the UK. Since then, we have had the joy and privilege of worshipping with several African diaspora churches, observing many similarities that cut across congregations, as well as a few differences.

that both indigenous and diaspora Christians strive not only to build a bridge between our disparate cultures, but have the courage to meet in the middle of the bridge rather than expecting the other to cross the span alone. Perhaps the following observations and suggestions will help us find our path to one unified Church.

Later on, we have belonged to two different multicultural churches in the towns we have lived in, both with an indigenous British majority. Both church communities welcomed us heartily and determinedly. We have had the opportunity to learn more about the indigenous Evangelical British culture as we observe and participate in dealing with good and bad news, joys and sorrows, fun and grief, praying and eating together as with any community. It is not always easy to accurately interpret cultural norms and expectations but having the attitude of learning on both sides has certainly helped.

Culture is the lens through which we view and interpret life. Our practice of Christianity intersects daily with both our own culture and others’ cultures. There are significant differences between African diaspora churches and indigenous British churches. Some are denominational, of course, but many are cultural. Yet, the British church must be committed to ‘one body’ (1 Corinthians 12:13), and being ‘one in Christ’ (Galatians 3:8) intentionally and practically.

In a world that is increasingly hostile to immigrants, simple gestures that communicate personal interest and warmth pass the message that we are glad to share our space and go a long way in building bridges of relationships. The way diaspora people are welcomed into an indigenous church community, for instance, is a key deciding factor of whether they stay and participate fully or feel excluded and eventually leave. In some cultures, welcoming strangers and making them feel at home and part of the family or community usually includes taking the

“It

teachable attitude .”

time to share stories about who we are, hopes, convictions, fears and all. People from other cultures may find this very difficult. For some, a simple general announcement of welcome is enough while others may need a personal and direct invitation into the community by the main leader. Going out of our way to understand what is considered a warm welcome from different cultural viewpoints is important.

In our quest to live and practice godliness together, the difference in our cultures (and how we feel, think and treat one another with regard to those differences) is a key point of consideration. It is therefore necessary and important that we all approach one another with an open, humble and teachable attitude if we are to live, worship and evangelise together in growing harmony.

Working together is not easy, even when we don’t have the added layer of cultural differences. It is vitally important, then,

Diaspora churches must work toward a similar goal by being open to people of other cultures. Whether by default or by design many diaspora churches tend to be monocultural, with a membership drawn from one country, sometimes even one single tribe. Although most diaspora pastors, when asked, strongly deny that their church is intentionally monocultural, there seems to be very little effort invested directly and intentionally in reaching out and inviting people of other cultures. On the other hand, a lot of programmes and activities

is ... important that we all approach one another with an open, humble and

are geared towards inviting people of the same culture to the church. In some cases, churches insist on retaining and preserving their African cultural norms, so they do not seek to become multicultural.

The genuine, welcoming hand of multi-ethnic fellowship will go a long way toward cultural understanding and gospel partnership, but we would be wise to take our bridge-building one step further. Authentic representation is an important way for indigenous churches to include diaspora people. This can be expressed in worship, ministry and certainly in leadership. There have been many discussions about this, with some asserting its importance and others being sceptical of its significance or feasibility. Some argue that it is not a biblical requirement, especially for leadership. Therefore, a starting point may be the need to develop a solid theology of diversity which is necessary for our current context of the global church. Practically, there is no doubt that representation matters. When we welcome different types of people to be influencers in our communities we gain a richer understanding that draws from the different perspectives in all matters. However, representation must be authentic if it is to be fair. Tokenism is a violation of Christian integrity and causes further division in the long run. We must therefore invest everything necessary to ensure that we have real diversity in our communities, be it discipleship, leadership development or cross-cultural training.

Likewise, diaspora Christians will need to put some effort into developing partnerships with indigenous and other diaspora ministries in order to benefit from the exposure, and also to share their own knowledge and experiences for the enrichment of the whole body of Christ. For diaspora Christians to be effective in mission and a prophetic voice in the UK, churches need to be mobilised to become more missional in their theology and practice, rather than being insular. While cultural identity is important, churches will need to develop a clear vision that embraces and prioritises the big picture of the purpose of God for all nations and overcome the natural tendency for cultural self-preservation.

Lastly, in order to cross the culture bridge together, we may need to handle the more difficult issues of diaspora engagement, one of which is racial prejudice. Like all immigrants, Africans experience both the challenge of integrating into a new culture with a different set of realities and the marginalisation related to the issues of racism. The majority of Africans coming to the UK experience the shock of racial prejudice and a new general identity – ‘Black’ – for the first time. This is a most difficult experience and some can be lost on what to do.

Racism is a sensitive topic in the British church for several reasons, including the biblical standard of equality that we all know but may struggle to live up to, and different levels of information and education on the subject. Diaspora peoples tend to engage with matters of race more closely since they find themselves in a minority position ethnically. Consequently, they seek more information and generally develop both more

awareness and more resilience around matters of race and racism and, therefore, tend to have less discomfort or stress around the subject, seeing it as something to be addressed, just like other issues affecting our unity in the church. Sometimes this frankness about racial issues is not well received, but ignoring the issue of racism only promotes racism, even if it is not intentional. As much as we may wish that racism doesn’t exist in evangelical circles, sadly, it does. Conversations about race may be uncomfortable to some. However, responding with silence, guilt, anger or indifference only serves to silence others rather than promoting real solutions to a real problem. We all need to develop resilience in order to listen to one another genuinely and to be able to handle issues of prejudices and our own unconscious biases, with the aim of promoting unity and the Christlike spirit.

reflection and mission strategy. African Diaspora Christians have many attributes that place them in a strategic place for mission in the UK. They have a rich missionary heritage that forms part of their memory, a ‘debt of love’ because of the many western missionaries who brought the gospel to Africa. For generations, African Christians have been evangelistic among their own people, hence a natural progression for their evangelistic zeal is to shift from local to global. Their passion for prayer and expectation of divine intervention in daily life positions them well to be able to pray for the nations with faith and expectations, if they are envisioned to do so. Their sensitivity to spiritual matters gives them opportunities to offer an alternative reality with conviction, in a largely secular and pluralistic society. This factor alone may very well be the key to the revival of interest in Christianity in the UK once again.

True partnership between indigenous British and diaspora Christians could be a pathway to revival, and this is what we all long for. Indigenous British churches have a lot to offer given the hundreds of years of theological

Overall, finding points of convergence rather than difference has great benefits. We may have many differences as human beings, but as the church of Christ, we have in common the most important aspects of life. Building bridges is not an easy task, neither is crossing them. However, as everyone does their part with diligence, we can meet in the middle. ‘Therefore if you have any encouragement from being united with Christ, if any comfort from his love, if any common sharing in the Spirit, if any tenderness and compassion, then make my joy complete by being like-minded, having the same love, being one in spirit and of one mind.’ (Paul, Philippians 2:1-2)

Originally from Kenya, Harriet serves as a mobiliser for the African diaspora with Pioneers UK. She also serves on the board of All Nations Christian College and the Executive Leadership Team for the Global Mobilization Network. She lives in Bristol with her husband Sam and their two boys.

Intercultural worship is the perfect way for diaspora and single-culture churches to engage with other cultures in prayer, outreach and fellowship and for multi-ethnic churches to grow cultural equality among worshippers. This article will show ways this can happen. I have had the privilege of delivering training for conferences and churches hosted by different ethnicities and I have noticed that white majority churches often aspire to build better community, while ethnic minority churches might desire to cross cultural boundaries for mission: two great motives for intercultural worship!

in his language created an instant connection— he attended her church and put his trust in Jesus. Wow! “

How can we see such things happening in our churches and cross-cultural encounters? How can we ensure that the dominant culture doesn’t marginalise others, unwittingly forcing them to “fit in” while leaving behind important aspects of their cultural background? The Apostle Paul gives us perfect guidance:

What then shall we say, brothers and sisters? When you come together, each of you has a hymn, or a word of instruction, a revelation, a tongue or an interpretation. Everything must be done so that the church may be built up. (1 Corinthians 14:26)

A Hindi song illustrates both of these. The Hindi-language song Amrit Vani * praises Father, Son and Holy Spirit; the leader sings each line and others echo it, accompanied by Indian instruments, or a hand drum and guitar, or simply with clapping. Once, after I included this song in a workshop, a Zimbabwean lady taught it to her choir in a Nigerian-led church. When they introduced it, an Indian “happened” to be visiting— staggered that they sang in Hindi. The next Sunday she brought a whole group of Indians, one of whom later joined the choir! A song like this is a powerful way to cross cultures and forge intercultural relationships. On another occasion, I emphasised how we can use songs like this for outreach. A Nigerian pastor present later reported how she sang this song over a Muslim young man in a London market. This Christian song

Paul says, “each of you” has a contribution to worship. No doubt this Corinthian church was diverse, since Corinth was a strategic cosmopolitan city in the Roman Empire, with Jews and Greeks (1 Corinthians 12:12-14), Romans and various tribal groups (see Colossians 3:11). Paul’s instruction fits the home-based assemblies of early Christians, where they met for the Lord’s Supper, prayer, teaching and singing (chapters 10-14). Today it is rare for churches to leave space for languages and musical styles of people other than the church’s primary culture. By contrast, Paul exhorts us to encourage the less-dominant people, so they too can benefit from worship—and that God will be glorified in our unified diversity:

Each of us should please our neighbours for their good, to build them up….6 so that with one mind and

one voice you may glorify the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. 7 Accept one another, then, just as Christ accepted you, in order to bring praise to God. (Romans 15:2, 6-7)

“Pleasing our neighbours for their good” means getting to know them, including discovering what releases their praise. It’s that simple—but will we lay aside our preferences to give them a voice? Will we join with their song, even if their language or style is a little different? It takes grace and humility on the part of all, but it follows the Philippians 2 model:

…in humility value others above yourselves, 4 not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others. 5 In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus. (Philippians 2:4-5)

We may feel uncomfortable about this but, if we are open to our fellow worshippers, we can usually sing short phrases in another language—until it becomes more natural. We might even find that such songs grow on us. As a start, we can use songs in other languages with sections in English (such as Multilingual Grace**). Then, over a few weeks, we can use everyone’s language in songs, prayers and Bible

readings. Leaders who introduce this carefully and gradually into their church take their congregation on a voyage into intercultural worship and deepening relationships. It equips church members for outreach too. As with Amrit Vani, a song in another language is a wonderful conversation-opener. Even the most language-challenged churchgoer can invite speakers of a song’s language to help with the pronunciation of a word in “a song we’re learning in church”!

Ian Collinge is a musician, ethnomusicologist and ethnodoxologist with WEC International and associate tutor in cross-cultural worship at All Nations Christian College, who, after several years in Asian ministry, founded WEC’s Resonance Multicultural Worship Band and Arts Release ministry.

If you want help or training in intercultural worship, email me (ian.collinge@wec-org.uk) or register for the Multicultural Worship Day (maybe bring a team), or the 4-day Multicultural Worship Intensive, both at All Nations Christian College (allnations.ac.uk/courses). For songs, check out Arts Release’s playlists, videos, and the songs2serve database, at artsrelease.org and songs2serve.eu, respectively. If you would like a Resonance multicultural worship band to visit your church or team, contact Arts Release at artsrelease.admin@wec-uk.org.

One last point: “intercultural worship” is deeper than “multicultural worship”. That’s because intercultural worship goes beyond the songs. It seeks to avoid tokenism and the privileging of one culture. It aims to give honour to people of all cultures by hearing their stories and engaging with their ways of worship. That’s how intercultural worship builds community and equips for mission. And… it’s fun! *You can see a video of Amrit Vani here: https://tinyurl.com/2tfez8ee **https://proskuneo.org/resources/songs/multilingual-grace/

Not that many years ago … one lunch-time in central London … a young, white, highlyeducated, professional Englishwoman took herself and her sandwiches through the open doors of an inner-city Church of England. She wandered around inside the church building, pausing here and there with obvious curiosity at what she was seeing. Noticing her, the vicar engaged her in conversation. “What is this building all about?” the young woman asked. Seeing she was wearing a crucifix on her necklace, the vicar replied, “It’s all about the person –Jesus - who is on your crucifix.” Whereupon – true story! – the lady pulled her necklace out to where she could properly see it and exclaimed: “I’ve always wondered who the little man on my cross was!” When Graham Cray, an Anglican Bishop, told that story, I laughed out loud. The bishop, however, was quick to urge that we shouldn’t be quick to incredulity, as this was now the commonplace amongst the young adult indigenous white population of the United Kingdom.

BY STEPHEN C DIRECTOR OF PIONEERS UKWhen Charles III was proclaimed king on 10 September, MPs across all the political parties were required to pledge their allegiance in Westminster. The majority did this by making their oath holding a Bible, swearing loyalty to the new king in the name of God. Several, including Keir Starmer - an atheist and the leader of the Opposition - chose not to swear on the Bible, making a secular affirmation instead. While I commend the personal integrity in

his choosing not to swear on the basis of a faith he does not profess, I was intrigued to discover that until 1828 one could not sit as an MP unless one was an Anglican! Sixty years later in 1888 a new Oaths Act enshrined the rights of MPs to affirm rather than swear on (Christian) oath. In 2022, post-Christian UK has its first Hindu as prime minister; it’s not impossible that we will have a self-proclaimed atheist as our next prime minister.

In 2020, Paul Bendor-Samuel of the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies wrote, “… significant movements toward Christ have been documented from within Islam, Hinduism, various strands of Buddhism, and ideological contexts of communism. Only secular materialism appears resistant to significant church growth” (my emphasis).

Maybe it’s not such a wonder, then, that our Chair of trustees and myself were at the receiving end of several pointed conversations during a recent visit to Nigeria, where we were meeting with the Church of Christ in Nations (COCIN) to discuss their specific request for a fresh missional partnership to unreached peoples between Pioneers UK and their large Nigerian denomination. Almost daily during our time there, we were engaged by bemused and concerned COCIN ministers and members and asked about the “decline” of the church in Britain – not just in its numbers, but also in its biblical values. One notable conversation began with: “Why do you people in Britain spend so much time and money on your pet dogs and cats?!”

COCIN was planted by our Mission (SUM) in the early 1900s and, for decades now, COCIN has been a missionarysending church itself – including planting churches amongst unreached people groups. One hundred years on from being founded, and COCIN has also sent a Nigerian missionary to plant a church amongst the ‘white, pagan, indigenous’ population of England. And COCIN are not alone in that.

I’m told that the largest single congregation in western Europe is The Embassy of the Blessed Kingdom of God for All Nations in Kiev, Ukraine. Nigerian, Sunday Adelaja, founded this church in his apartment with 7 other people in 1993. By 2013, the church claimed 25,000 members in Kiev, 100,000 members in the rest of Ukraine, and 1,000 churches in the rest of the world. The largest single congregation in Britain today is Kingsway International Christian Centre. It was founded in 1992 in London with 200 adults. Not too long ago, it was reported to have a Sunday attendance of 12,000 (predominantly of West African origin). Its senior pastor is Matthew Ashimolowo, a Nigerian.

The Nigerian-founded Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG) established its first church in the UK in 1991 and now has over 800 churches throughout the UK – including one, would you believe, in the small town of Bawtry, South Yorkshire where our Mission’s office is located! RCCG’s stated mission includes “planting churches within five minutes’ walking distance in every city and town of developing countries and within five minutes driving distance in every city and town of developed countries”. How about that for a vision?!

“Significant movements toward Christ have been documented from within Islam, Hinduism, various strands of Buddhism, and ideological contexts of communism. Only secular materialism appears resistant to significant church growth.”

Notwithstanding, a question continues to rise to the surface for me: How well set up is the Afro-diaspora church in the UK to reach out in effective mission to the indigenous white population of the UK … let alone other diaspora communities in Britain? And why is there not a ministry partnership between the church-planting Nigerian RCCG minister and the evangelical churches already present in Bawtry to reach out to the very-predominantly white population of this town?

of its kind in Europe”. Among its key findings, the study asserts that Chinese churches have become the fastest growing Christian community in Britain since 2021, due to Hong Kongers. There are now more than 200 Chinese Christian communities in the UK, according to the study. No wonder then that Chinese pastors in the UK report their congregations have doubled or tripled in size since January 2021. One church in Manchester has multiplied from less than 200 attendees to 1,200 due to the recent influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Of course, the UK diaspora Christian scene is not limited to the Afro-diaspora church!

Britain’s Chinese diaspora is the oldest in western Europe. According to official data, the Chinese now make up the largest group of immigrants from any country into Britain. Then there is the Hong Kong factor, with three million people newly-eligible to come to the UK. Maybe as many as 100,000 have already arrived from Hong Kong into Britain since January 2021.

A new study has estimated almost 1 in 4 Hong Kong immigrants to the UK are Christian (many being pastors or Christian workers). Led by Yinxuan Huang, a research fellow at the London School of Theology, this research project on Chinese Christianity in Britain is billed as the “largest study

We don’t yet know what impact this significant influx of Hong Kong Christians will have on the UK Chinese church, or to what extent these Chinese diaspora churches in the UK will be minded to reach non-Christians (of whatever ethnicity or religious worldview) in their communities; let alone mobilise to the unreached peoples of the world.

The urban UK of today has many churches planted by African, Latin American, Caribbean and Asian Christians. Israel Oluwole Olofinjana writes that “Reverse mission starts with a deep sense of gratitude from those who have benefited from historical European mission activity …. It is this sense of gratitude, combined with the understanding that Europe also has need of missionaries, that has led to missionaries being sent to the UK from across the majority world (that is, Africa, Caribbean, Asia and Latin America).”

This Reach edition is all about ‘diaspora’ – not just that there are huge numbers of diaspora peoples in the UK, but that there are also quite incredible numbers of vital and growing diaspora churches in Britain. What does this mean for traditional missions in our country? Closer to home for me, what does this mean for Pioneers UK?

As a UK mission agency, I see our relationship to diaspora Christians and churches in Britain as someone invited

alongside to help light the fire of inter-cultural missions within their very bones and spirit – with the ultimate goal to help these diaspora brothers and sisters to crossculturally send well-equipped workers to those peoples yetunreached with the good news of Jesus Christ as Lord and Saviour.

It would set a fire within my bones to see such a partnership between us that results in a mobilising of the different UK diaspora Christian communities such that, for example, Chinese Christians are effectively making disciples amongst unreached peoples who are both Chinese and non-Chinese … both in the UK and overseas.

I am so grateful to God that Pioneers UK has already embarked upon the journey of partnering with the Afrodiaspora church in the UK to see Afro-diaspora Christians mobilised to unreached communities within the UK and beyond. I want to see us build this exciting partnership more and more strongly. It is a particular joy that we are also responding to invitations to partner with the African church and Christian agencies in the global task of planting the church of Jesus Christ amongst unreached peoples in Africa and beyond.

A final story about the crucial nature of working together…

You might be surprised to learn that roundabouts were invented in America – even though most Americans don’t like roundabouts! The first circular intersection designed for vehicles was Columbus Circle in New York City, opened in 1905. However, as more and more roundabouts were constructed in America, not only did gridlock result but more and more vehicles were crashing into each other. By the 1950s, most Americans had concluded that roundabouts weren’t effective at all, and America stopped constructing them. Thankfully, the British came to the rescue!

In 1966, we figured out what the Americans were doing wrong. According to the original design of traffic circles, entering vehicles had the right-of-way, so drivers charged in at high speed without watching out for vehicles already on the roundabout. We British realised the Americans needed to reverse the right-of-way, instead giving priority to the cars already on the circular intersection! Once the correct rightof-way was established, things improved mightily. Hurrah!

Of course, the point of the modern parable of the roundabout is not that the driver of the vehicle already on the roundabout is more important than the one approaching it. Rather, the roundabout teaches us that coordinating an effective prioritised sequence of traffic flow is crucial for all sorts of benefits.

No analogy is perfect (!), but a crucial need for the church in the UK – this church of many colours – is to coordinate together for the sake of missions in our age. It’s not a question of which church – diaspora or indigenous - is more important or significant. It’s a question, rather, of how the whole church in the UK can work in fellowship together to reach not only a worlds’-spanning community within the UK (including the unreached secular materialists) but also the yet-unreached peoples over the seas from the UK.

A crucial need for the church in the UK is to coordinate together for the sake of missions in our age.

Our nation is filled with Christians of all backgrounds - Chinese, Iranian, Ghanaian, Nigerian, Kenyan, Indian, Mongolian, Thai, Vietnamese, and British-born people of all races, classes and political persuasions. Our challenge in 2022 and beyond is to open ourselves up to the kind of intercultural partnerships that will make the truths of the gospel of Christ even more attractive to those who don’t yet know Him. The exciting thing is, it’s already happening! All over our nation, mostly-white indigenous British churches and mostly-not-white diaspora churches are partnering on both national and local levels to reach the unreached in their cities and neighbourhoods. Both our trustee, Ebenezer, and our London team leader, Kefas, pastor diaspora churches in the UK. They’ve graciously shared with us their own stories of partnering with indigenous churches in their neighbourhoods.

Workingin partnership is something that’s been my passion and something I’ve been working towards. We don’t want to just be talking about this, but we need to be doing it. Our local church, which is predominantly African diaspora, works very closely with a very middle class, white church in Leeds. We have a very good relationship, even at the leadership level, and also we do a lot of programmes together. The good thing is, we are more or less within the same community, the same postcode. We actually have a project together in the community. They have a congregation of about 1000 and they’ve got resources. They’ve rented a café in the community; it’s called the Welcome Café. Most of the people in the local community are migrants, mostly from the Horn of Africa — Eritrea, Somalia — and mostly Muslim. Because we are Africans, we are able to engage these migrants easier. So we work together at the café. Some of our church members volunteer there, and the resources are provided by Bridge Community Church. By working there together, we are able to engage with this migrant community. It works very well. It’s a very good partnership.

Our relationship with them grew organically. We met one of the facilitators from that church and we became friends when we were doing the Kairos Course. And through that I got to know their church leaders, the three pastors in that church. Once the relationship is there, the trust is there. Three years ago, before Covid, we were doing a big conference together at their church and one of their senior pastors (they’re all white pastors) was introducing me to someone and said, “Oh this is Ebenezer, and he’s a good man. He’s from the Assemblies of God.” He felt confident to introduce me to somebody. There was some credibility there. And that comes through relationship and people getting to know each other organically.

BeforeCovid, we shared a building with a local church. It was a Church of England, and we are a COCIN (Church of Christ in Nations) church. Both of us believe firmly in Christ, we believe in the Trinity, we believe in one baptism, one faith, and so on. When we first started, they would come and have their Christmas service in the morning, and we would come and have it later. Or at Easter, they would meet in the morning for their Easter service, and we would meet in the evening. Because of my desire to see a partnership with the local church, I didn’t see any need for us, who have the same confessions, and who have the same points of agreement in the main issues to be worshipping separately.

So I approached the vicar, and I told him, “I don’t really see any sense in that. We don’t preach a different gospel. We use the same Bible. I think we have a responsibility to demonstrate our union, our oneness in Christ, a little bit more.” I told him, “Left to me, I wish we would just merge and work together or, at least, let us begin to break the barrier by having some joint services.” So he asked, “Like what?” and I suggested: “Christmas is universal for all Christians. Why should we have separate services? Let’s have a joint Christmas service. Let’s have a joint Easter service.” Of course, the next challenge was going to be which liturgy we should use. And I told him, “For me, the most important thing is our union and not liturgy. I am happy for us to go with your liturgy, and let your service be organised in a manner that would be comfortable to you. You are our hosts. I’m the one seeking partnership and fellowship.” So we experimented the first year, and it was so welcomed by the members because we brought in our African flavour, we brought in food and drink, and we brought in dancing and rejoicing. It was a little different, but it was a good difference.

We thought it was just going to be an experiment, but right after the service, the members on both sides insisted that this must be the way going forward. And that, for me, confirmed the fact that our insistence on our separate identities was not exactly what the body of Christ hungered for and yearned for. During those services, the service would contain liturgies from both traditions, and it gave us such beautiful variety, and yet our commitment to preaching the gospel was not compromised. It was wonderful fellowship.

Well, that, for me, began laying the seeds for this concept of partnership that had been growing and brooding in my heart. After Covid, unfortunately, that congregation could not continue. We still rent the property, but the members have stopped worshipping there. The few that have remained have moved to another congregation of the Church of England that is not far from us. And even the vicar has been moved to that other congregation. So it has thrown us back to where we did not want to be.

But we are committed to seeing how we can partner and have joint services, so at the last Acton Ministers’ Fellowship, I approached some of the pastors and I asked them, “Why can we not unite the churches? Why can’t we unite and hold services together, and have a stronger expression of our oneness in Christ within the community, so that the community will not see members of the Baptist Church or COCIN or AME or any other, but they will just see a body of believers who are happy to come together and worship. Wouldn’t that be a wonderful testimony in the community? Well, we are exploring that. It will take patience, but I’m committed to following that up.

BY KEFAS, PIONEERS’ LONDON TEAM LEADER

BY KEFAS, PIONEERS’ LONDON TEAM LEADER

About ten years ago, the leadership of my denomination in Nigeria, the Church of Christ in Nations (COCIN) met with some former missionaries from the Sudan United Mission, which is now Pioneers UK. These former missionaries had helped plant and nurture our denomination for many decades. As they were talking, the conversation tilted to their experiences when they came back to the UK, and whether they returned to the same United Kingdom that they had left, particularly as it relates to their faith. It became clear that many of them were sad, that they had left a United Kingdom that was fervent for the gospel of the Lord, that had churches filled up, and people who were committed to sending missionaries and supporting the work of the spread of the gospel all over the world. But they returned to a United Kingdom that had become very secular, where attendance in church had drastically fallen, and where young

people were no longer committed to going to the mission field. In fact, many parents were no longer taking their children to church, such that the new generation of young people did not have the heritage of faith in God and worship passed down to them. COCIN’s leadership felt that, comparatively, looking at the rate of growth of Christianity in Africa, the place that needed the gospel now was the UK. And just as they were thinking about that, they also sensed a need for renewing and strengthening COCIN’s relationship with the former missionaries and the mission agency that sent them. So the need for these two things came up, and that was when the idea of reverse mission came to the mind of our leadership.

The assumption was that in this ‘secularised and backslidden’ United Kingdom, COCIN would come with a fire and galvanise

people, mobilise churches and bring light back to this ‘dark’ continent. That was generally the assumption in Nigeria. We concluded that what we saw on TV was a true picture of the lives of the people. We felt ungodliness had taken over the land and there was the need for us to bring back the light of the gospel. So I was sent with a clear mandate: plant a COCIN church and restore our relationship with the former missionaries and the mission sending agency.

orphanages to help. Nobody considers reaching out to people on the streets. Nobody considers reaching out to the homeless as an act of demonstrating our Christian faith. But here, I found that there are organisations such as Christians Against Poverty that are actively involved in getting people out of situations of indebtedness, liberating them, so that they would be free to get back on their feet.

On arrival in the UK, what did I find? There were huge church buildings, especially in London, and yet these churches were not populated. In some of the churches that we went to, my wife and I were nearly the youngest in the church - and back in Nigeria, I would be considered an old man! Then, as I moved around and began witnessing on the streets, there a was lack of interest in the things of the Lord. So that began to confirm the impression I came with.

But as time went on and I began to interact more and more with churches and church organisations, I found out that our assumption in coming to the UK was not correct. Yes, numerically speaking, the number of people that openly profess their faith was really small and the number of people that would meet in church would not necessarily be large. But I found an active faith that falsified the assumption I had. I found that though there wasn’t an expressive faith, there was a demonstrative faith. The faith that I encountered was faith that was seen more in action, faith that was seen in caring for the needy, faith that was seen in taking care of the helpless, faith that was strong in social action for the good of the community, faith that showed deep interest in the personal affairs of people and would create opportunities for people to get help, a faith that would seek to befriend the lost and to present Christ in a quiet, non-noisy manner.

It occurred to me that God didn’t have to come from Heaven get them out of poverty, but he instead created for them a Christian community where their needs were met, as is the case in the church in us. I began to see a vibrant Christian faith everywhere. I saw churches that were open during the week, and the homeless would go there and eat for free and nobody was holding a hammer over their heads, saying, “If you don’t repent, you’re not going to eat.” No, no. It was faith in action, faith that showed love, that invited the sinner and created a place for him not to feel judged.

In Nigeria, we have orphanages. If you want to support them, you just give them money. Nobody considers going to

I was put to shame by these discoveries. Yes, I didn’t see the Christianity where people stand on street corners and shout and

where their needs were met.

preach and make noise. I didn’t see great crusades happening. But I saw demonstrations of a commitment to Christ, by people who love Christ and who are sacrificially doing so in a quiet manner.

In the course of evangelising in the park, I met other Christians who they said they had also come out for evangelism. And yet they were so winsome about how they would go about it. I discovered that, while I would meet people and encounter them in a confrontational manner, they engaged people in conversations that were not confrontational or judgmental or even strictly Christian. That surprised me. I saw an expression of the Christian faith that was really there - it was active, and strong, even though it was not as visible or as loud as I would see in Nigeria.

were willing to receive the gospel. And they received it because they found, in us, people who actually cared about them. So I now understood why this social expression of Christianity was so effective, because those who were neglected, those who were invisible and had great need, suddenly found their needs met, and they were coming to Christ.

That humbled me; that challenged me. It made me come down from my high horse of spiritual superiority. So from seeing myself as the one who came to bring the light to restore the United Kingdom, I found that I was the one that needed my view of how to express my Christianity helped. It helped me not to do ministry from a place of arrogance, but from a place of great humility.

This began to affect the way my wife and I went about doing ministry. We began to look out for the same kind of people that these other Christians were looking out for. The people who are most receptive to the gospel were the rejected ones: ones that we would have easily judged - the homeless, the drug addicts, the alcoholics, and so on. That was when we started focusing on them. We could see that these were people who

During this time, I attended a function of Christians Against Poverty, and I left in tears because I heard testimonies of people who, for example, their marriage was at the brink of collapse because of indebtedness and other issues. But suddenly, with the intervention of Christians Against Poverty, not only was their home restored, their faith was restored, their confidence was restored, and they became committed to supporting the work of Christians Against Poverty to help others. Now...what else could you want? That is such a clear example of having discipled someone who goes on to then disciple others because that person has been blessed.

I realised that the best approach is to just go quietly in the leading of the Spirit of God to discover what he is already doing.

In Nigeria, we judged that God was not working in the UK. We decided we needed to send this missionary who would come and change things - only to find out God works in different ways among different people for His glory. So we started ministry, and God brought different groups of people to our church.

The church was growing. But after Brexit, the homeless and alcoholics were taken away from Acton, where we have our ministry. We lost them...and they were the chunk of people in the church who were not Nigerians. When they left, the church was basically just Nigerians. That was not pleasing to me, because we were not sent here to reach out to Nigerians. So we would go out and engage in vigorous evangelism, and we would invite people to church. They would come to church once or twice, and then not come again. So I tried to follow up, and they said, “Well, it’s a Nigerian church.” Even those who were Africans from different countries were not comfortable coming to the church because they felt it was a Nigerian church.

that church so that they became a part of that church? Would that church have remained a weak church? Would it see a loss of members or would it experience a boost and growth? Even if it was a church populated by whites alone, if I joined it, and other Nigerians came and joined, would that not bring greater life and dynamism in the church?

And, as though to prove this, I started getting invitations from churches in the UK to come and partner with them and be on their ministry teams. In fact, one church was bold enough to say, “Kefas, leave COCIN. Come and join us.” That sounded like an answer to prayer, but somehow I felt it was a temptation because I felt if I had yielded, I told them, “If I leave COCIN and join you, then you will never trust me, because it means I can leave you to go and join someone else.” But that confirmed to me that this was the way to go.

So I began to wonder, what is the problem? The more I prayed about it, the more I became convicted that the strategy we were adopting for ministry was not particularly helpful. Why? Because here I am in the land of a different people, having come with the understanding that the church in the UK is struggling, and yet, I have not joined any of the weakened churches to make available my strength, my wisdom, my gifts, my grace, my calling and everything that God has given me. I’m not joining them in the work. I am working against what they’re doing. I found this very troubling.

So I began imagining: what would it look like if, on arriving, we had located a struggling church and made ourselves members and brought to bear our gifts and grace? Then, the few Nigerians we were able to reach out to, we invited them to

What would it look like if, on arriving, we had located a struggling church and made ourselves members and brought to bear our gifts and grace?

So what is the way forward? There is a need for us to develop partnerships that lead to strengthening the church in the UKnot strengthening COCIN, not building a denomination. One of the strategies that I’ve shared with COCIN leadership is, if the relationship with Pioneers grows, instead of saying, go and plant a COCIN church, it would be to approach Pioneers UK and say, “We have workers that we want to send, to come alongside local churches, to strengthen them, to be members, to encourage them. If you will accept them, we are releasing them to you. Send them to any churches where you think they would be a blessing, and they will settle in those communities.” So that’s one strategy.

The other strategy I told COCIN that we would be adopting, which I intend to start work on now, is this: There’s been high migration of skilled workers, intelligent young men and women from Nigeria, most of them fervent believers, some of whom we know. Some have come to the UK to study with the intention of remaining in the UK, since there is that permission. Some are professionals who have relocated to the UK for work. So I said, “This is a ministry opportunity. Why should these people come on their own? We can work together to help them settle in communities and churches in the different towns where they are, where they will not join Nigerian churches where they can just hide away and enjoy themselves. In fact, I am committed to ensuring that all COCIN members who come here to study don’t join a Nigerian church in the UK. My desire is to see them join the local churches, to be a part of the life of the church, to work in the church, bringing their gifts and skills to bear in worship, in service, in the community. I want to encourage them that if the Lord provides an opportunity for them to serve him, to go ahead and do so, because I think that is the way we can help restore and be a blessing to the church.

church is not strong. I look at the Nigerian churches, the Kenyan churches, the Ghanaian churches, all diaspora churches, and in my mind I’m imagining: “Supposing we collapse all our churches and all our members enter local churches. Overnight the church in the UK will grow and it will be strong. What’s the point of having a church pastored by a Nigerian that has 10,000 people gathering on a Sunday, meanwhile in that same community there are local churches that have been struggling to hold the light of the gospel up. And we look at them and we say, “You are losing it, you are no more alive.” Meanwhile we are the ones that have not stoked the flame that they have been trying to maintain.

Earlier this year, I started sharing this idea with other Nigerian pastors, and of course it was not popular because I was literally telling them that we are doing the wrong thing and we should stop. But I feel that we are the reason why the indigenous

So I feel we have a responsibility, and it may be an unpopular one, but I am committed to telling my fellow diaspora pastors that I think we are not doing God a good service by maintaining our diaspora churches. We have become empire builders. We are just building little kingdoms in our churches instead of building the body of Christ. So the way forward, for COCINI’m discussing this with them - is to seek partnership that will not necessarily spread the building of a COCIN empire, but to strengthen churches in whatever country we go to. That is the message I’m sending.

It was a surprise and an honour when we recently received a legacy gift from Miss Paula Hudson who sadly passed away last year.

After university, Paula trained with the civil service to become a VAT tax advisor. Her good friend Kathryn Hill told me in a recent conversation how she insisted on standing up for the owners of small businesses who were so confused in the early days of VAT and help them as much as she could as she travelled around the South East inspecting and advising with care and concern.

Paula met Kathryn in the early 70’s when they were both in Canterbury, then when Kathryn went to Nigeria with Sudan United Mission (now Pioneers), Paula supported her. Later when Kathryn was raising support for poor and disabled students at our mission’s Boys Secondary School [BSS], Gindiri in the 80’s Paula signed up and was paired with a young boy called Dakam Polycarp who not only did well at BSS but went on to become a colleague of Kathryn’s at Gindiri Material Centre for the Handicapped and now works at the University of Jos, Nigeria.

Paula moved to Petersfield when her church was planting a new congregation and later worked in the Christian Bookshop there. Kathryn remembers her fondly as a very caring person with a love of cats and gardening. And how selfless and caring she has been over the years with her financial support and now her legacy to Pioneers.

What a lovely reminder of how we can touch people’s lives and further God’s mission through our faithful giving. Thank you to everyone who regularly supports our work and has considered a gift in their Will. ~

Our interview with Ebenezer, Pioneers’ trustee and the founder of the Afro-Diaspora Mission Network, was so full of thought-provoking ideas, we couldn’t bear to leave any of it out! So here is Part 2, where our editor, Amanda, asks Ebenezer to share his ideas about how diaspora and indigenous churches might go about achieving true gospel partnership.

Amanda: I’ve lived cross culturally a few times and I really value the things that engaging cross-culturally can bring to a person. Some parts of it are hard—the culture shock and cultural misunderstandings and so many other things that can go wrong - and yet it’s so rewarding at the same time. I wouldn’t change the things that I’ve learned from my cross-