2 minute read

Ethnic Diversity

Lack of ethnic diversity is something the Walt Disney Company have been regularly criticised for by the public. Many of the films are retellings of classic stories as highlighted by Hoffmann: “imbued with the values of a different time and place” (60). However, they often end up stereotyping and perpetuating: “the values of one class, ethnic group, or other social segment” (Hoffmann, 60). This dominant white, male viewpoint is problematic for a contemporary audience.

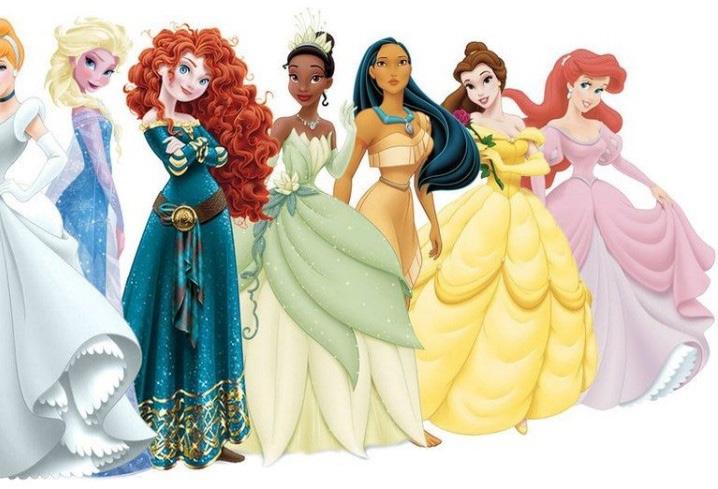

Twenty-six years after Walt’s death in 1966, Princess Jasmine (1992) was introduced as the sixth Disney Princess. She also became the first non-white Princess. Three years later in 1995, Disney made Pocahontas and then three years later Mulan, finally adding racial diversity to the collection. Eleven years later, the next colored Princess was Tiana from The Princess and the Frog (2009). Although Tiana is an African American Princess, she only gets a small amount of screen time as a black Princess before being turned into a frog, limiting the time where the viewer can see her skin colour.

Advertisement

As well as lack of ethnic representation, Disney have tried to move onward from the uncomfortable images of racial and ethnic stereotypes so prominent (in retrospect) in some of the Disney classics. Controversy has arisen due to the ethnic caricatures depicting Asian (e.g., the Siamese cats (Peggy Lee) in Lady and the Tramp (1955) (King et al. 2); the cats in The Aristocats (1970) featuring thick accents and playing the piano with chopsticks, and black African ethnicities, e.g. the crows in Dumbo (1941); and King Louie the ape (Louis Prima) in The Jungle Book (1967). Criticisms have been placed on films such as Peter Pan (1953), with the stereotypical interpretation of Native Americans as “redskins”, although at the time, this portrayal wasn't controversial. The song "What Made the Red Man Red" and lines such as "Peter Pan save me, me his velly nice friend” and “Me no let pirates hurt him" from the chief’s daughter Tiger Lily is clearly a very crude stereotype. There are examples of Disney more often and more accurately, depicting other cultures in their more recent films, for example Encanto (2021) which depicts a Colombian family, and Coco (2017) which is a story about a Mexican boy (Towbin 37). However, these characters from other cultures are typically not a Princess, “non-dominant groups are (still) portrayed negatively, marginalized, or not portrayed at all” (Hoffmann 65).

The fact that in 2023, only four out of the thirteen Disney Princesses aren’t white is a source of frustration for many (fig.5). Not only is this misrepresentation shown in the films but also in Disney’s retail stores (in person and online), which attract millions of visitors each year. Stores sell a wide variety of merchandise to go along with the films, including toys, costumes, clothing, and collectables (Fisher). But if only four out of the total thirteen Princess films feature women of colour, this means that less than 30 percent of the store will sell items featuring non-white characters. Children of colour likely do not see themselves represented by the Princesses in the same way that white people are. The impact of this marginalization and lack of recognition was noted by black, feminist writer Audre Lorde who stated, “in our world, divide and conquer must become define and empower” (Lorde 19). As a global brand it is Disney’s responsibility to ‘define and empower’ people of all shapes, sizes and colours.