2 minute read

Gender Roles

The roles of the female characters have also been highly gender stereotyped. In the hands of male tellers in a predominately male company, the leading ladies and heroines in the Disney films tend to be depicted as passive, if not helpless, without a man to help them. Barbra Ehrenreich highlights:

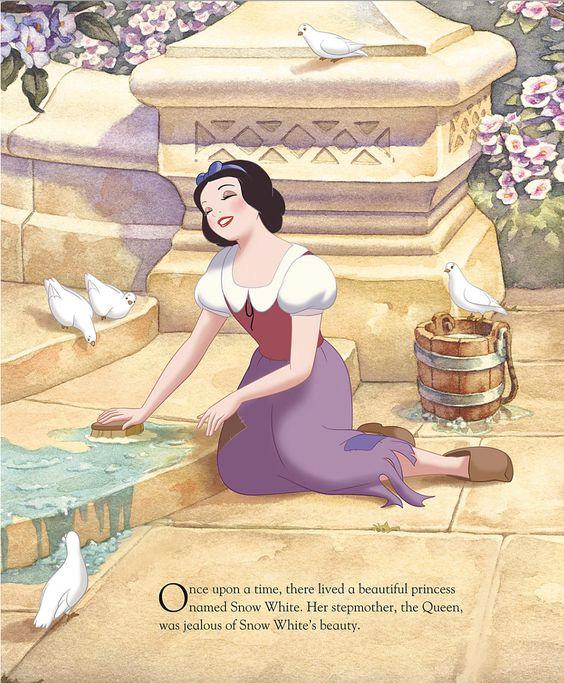

Disney likes to think of the Princesses as role models, but what a sorry bunch of wusses they are. Typically, they spend much of their time in captivity or a coma, waking up only when a Prince comes along and kisses them. The most striking exception is Mulan, who dresses as a boy to fight in the army, but–like the other Princess of color, Pocahontas–she lacks full Princess status and does not warrant a line of tiaras and gowns. Otherwise, the Princesses have no ambitions and no marketable skills, although both Snow White and Cinderella are good at housecleaning. (Ehrenreich)

Advertisement

Films are vehicles for self-exploration and understanding of the world and how it works; young children constantly seeing either the same body type, or females being rescued by a handsome strong man, will certainly have implications for how they view not only themselves but also others around them. As Audre Lorde said, “As women, we have been taught to either ignore our differences, or view them as cause for separation and suspicion” (Lorde 18). In Disney, differences between males and females are emphasized in a way that unhelpfully creates division.

Studies have shown that children’s behavior, attitudes, and self-esteem are impacted by the films and TV they watch (Livingston and Bovill). The portrayal of the Princesses in Disney’s films helps make ‘crucial contributions’ to the most paramount view of the self, subconsciously informing children how women ought to act, think and dress (Miller and Rode 86). In Sleeping Beauty, Princess Aurora only had 14 lines throughout the whole film, along with her songs (Griffin, et al 880). Altogether in the Disney Princess animated films the male characters speak between 68% and 77% of the time, effectively silencing female characters (Fought & Eisenhauer, 2016). Amy M Davis examined the Princesses in ‘The Classic Years’ (1937-1967) stating their representation was “largely static” (Davis 137). She argued that the princesses were at their least active and dynamic as they carried out traditional feminine roles such as domestic work and passivity. The lyrics from Snow White’s song ‘whistle while you work’ (on the right) quite literally give the message that cleaning up after seven lazy men is good fun (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, ‘Whistle while you work’, 1937).

‘Just whistle while you work

And cheerfully together we can tidy up the place

So hum a merry tune

It won't take long when there's a song to help you set the pace

And as you sweep the room

Imagine that the broom is someone that you love

And soon you'll find you're dancing to the tune

When hearts are high the time will fly so whistle while you work

So, whistle while you work.’

There is a stark contrast between ‘the Snow-White (fig.11) type of Disney Princess’ and some of the more contemporary counterparts which circulate a more modern set of gender norms (Davis 35). The era of more self-sufficient Princesses emerged; Princess Merida (Brave)(fig.12) for example, a Princess who doesn’t need a prince, who saves herself and her family on her own, and who ultimately remains single at the end of the film. More empowering storylines have also appeared in other Princess films such as Mulan, Frozen and Princess and the Frog. In Good Girls and Wicked Witches Davis argued this shift arose after Walt’s death, releasing them from traditional gender roles, giving them more independence and a stronger sense of purpose and personality in the films. The change may also have happened organically along with gender norm changes in the real world, especially when coupled with the expansion of social media use, which gives a greater voice to public opinion, and which encourages responses in reaction to this opinion.