BU I LD I N G BU LFI N CH By April 1818, materials for the new schoolhouse were being secured and in May architect Asher Benjamin was paid for his design. The site chosen was not where the second academy had stood, close to where the Armillary Sphere now stands. It was on “the height of ground southeast of the house now occupied by the principal,” John Adams. Relocating the schoolhouse put it more directly under the eye of Adams and opened up the full extent of what was then known as the Seminary Common, now the Great Lawn. In the nineteenth century, the campus was dominated by the Andover Theological Seminary, with its primary buildings ranged along the east side of the Common, beyond the path and double row of trees that came to be known as the Elm Walk. The new location was calculated to relate the Brick Academy to the Seminary buildings in its setback from and elevation above Main Street, just as the use of brick related the schoolhouse to the Seminary buildings.

Boston maker of picture frames and mirrors, $5.40 to gild the weathervane that would top off Bulfinch Hall in 1819. All in, the project cost $13,252.73. Most work was performed by masons and carpenters. Master mason Simeon Marshall was responsible for several buildings on campus, including Pearson Hall— just being completed when work on Bulfinch began. Marshall led a crew of seven masons, assisted by nine hod carriers. Ten carpenters working on the project were led by David Hidden and David Rice. They came to Andover from Newburyport in 1809 to work on Phelps House, married locally and stayed. Like Simeon Marshall, they played leading roles in construction of Pearson Hall; they continued to build on campus through the 1830s, sometimes in partnership, sometimes individually.

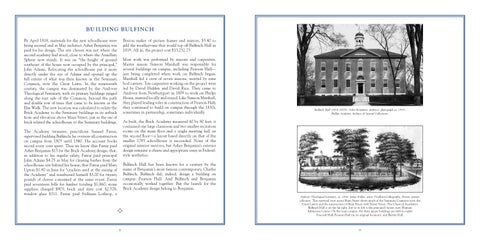

Bulfinch Hall (1818–1819); Asher Benjamin, architect. photograph ca. 1910; Phillips Academy Archives & Special Collections.

As built, the Brick Academy measured 40 by 80 feet; it contained one large classroom and two smaller recitation rooms on the main floor and a single meeting hall on the second floor—a layout based directly on that of the smaller 1785 schoolhouse it succeeded. None of the original interior survives, but Asher Benjamin’s exterior design remains: a chaste and appropriate essay in Federalstyle aesthetics.

The Academy treasurer, punctilious Samuel Farrar, supervised building Bulfinch; he oversaw all construction on campus from 1803 until 1840. His account books record every cent spent. Thus we know that Farrar paid Asher Benjamin $15 for the Brick Academy design; that, in addition to his regular salary, Farrar paid principal John Adams $4.75 in May for clearing bushes from the schoolhouse site behind his house; that Farrar paid Mary Upton $1.90 in June for “crackers used at the raising of the Academy” and reimbursed himself $3.00 for twenty pounds of cheese consumed at the same event. Farrar paid seventeen bills for lumber totaling $1,860; stone suppliers charged $903; brick and slate cost $2,378; window glass $311. Farrar paid Stillman Lothrop, a

Bulfinch Hall has been known for a century by the name of Benjamin’s more famous contemporary, Charles Bulfinch. Bulfinch did, indeed, design a building on campus: Pearson Hall. And Bulfinch and Benjamin occasionally worked together. But the laurels for the Brick Academy design belong to Benjamin. Andover Theological Seminary, ca. 1830; James Kidder, artist; Pendleton Lithography, Boston; private collection. This eastward view across Main Street shows much of the Seminary Common (now the Great Lawn) and the intersection of Main Street with Salem Street. The Classical Academy’s Bulfinch Hall is on the far right. Just to its left is the principal’s house, now Shuman Admission Center. On the main campus, the three major buildings are (left-to-right) Foxcroft Hall, Pearson Hall (in its original location), and Bartlet Hall.

8

9