6 minute read

Lower Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS)

Gendy Bradford, Nurse Manager Gastroenterology Day Service, Waitaha, Canterbury Gendy.bradford@cdhb.health.nz

In August 2022, I was fortunate to receive financial support from the New Zealand Gastroenterology Nurses College (NZgNC) so that I could attend the Gastroenterology Nurses College of Australia (GENCA) conference in Sydney. The theme of the conference was innovation, sustainability and growth. It was the first time I had attended an international conference in a few years, so I was both excited and a little nervous. Whilst at the conference, I was keen to hear presentations on topics that were unfamiliar to me. As a result, I attended a presentation by Carol Chan, a physiotherapist in Sydney, titled ‘Ano-rectal function after anterior resection for Colo-rectal cancer ’.

Advertisement

Carol graduated from the University of Sydney and is a registered physiotherapist with extensive clinical experience in pelvic floor disorders. She is currently undertaking a PhD through the Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney. Her study investigation is on bowel dysfunction (anterior resection syndrome) after colorectal cancer surgery and treatment, with complex anorectal dysfunction. Carol’s topic of study came about from her experience in clinical practice where she encountered many patients who described bowel symptoms such as increased frequency of defecation, urgency, loose bowel motions, incontinence and constipation after anterior resection surgery. Patients reported that these symptoms significantly affected their quality of life (QoL) and they were frustrated that surgeons didn’t appear to understand the long-term health effects once the surgery had been completed nor did they prepare the patient for this outcome.

What is an Anterior Resection?

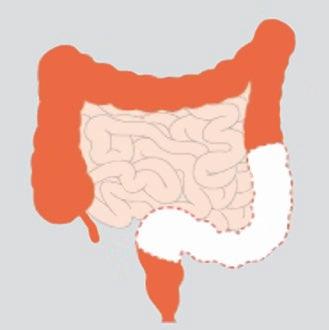

An anterior resection (AR) is an operation most commonly performed for bowel cancer, to remove part or all of the rectum and part of the left side of the large bowel. It also includes the removal of the surrounding lymph nodes to prevent the spread of cancer and its recurrence. After the segment of bowel is removed, along with its blood supply, the two ends of bowel are joined together (anastomosed) with stitches or stapling devices above the pelvic peritoneum. This enables the anal canal to be preserved and the bowel can be brought down to join the rectum or anus without compromising the bowels blood supply (https://www. colorectalsurgeonsnewcastle.com.au).

What is a Low Anterior Resection?

A low anterior resection (LAR) refers to the removal of the diseased portion of the rectum, the sigmoid colon, lymph nodes and fatty tissue with the anastomosis occurring below the pelvic peritoneum but higher than the anal canal (https:// www.ccalliance.org).

What is Low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS)?

The term low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) is often used to describe the symptoms and consequences of bowel dysfunction that patients experience after rectal cancer surgery. LARS is a highly prevalent outcome affecting up to 44% of patients and can be long-standing, often persisting up to 18-months after rectal surgery. It is consistently associated with poor quality of life, and ‘as access to rectal cancer treatment improves, it represents a growing burden of disease with significant patient- and healthcare burden’ (Benli et al 2021). However, despite the high prevalence of LARS, the NICE Guideline NG151 (2020) found that ‘patients report they are often not asked about their symptoms’ and their LARS is often not recognised. If not specifically asked, patients do not report their symptoms, assuming it is a normal consequence of their disease and treatment ’.

LARS is often exacerbated by factors such as low anastomotic height, defunctioning of the colon and neorectum (surgically formed rectum) and radiotherapy (Varghese et al 2022). A recent international patient-provider initiative (cited Keane et al 2020) established a consensus-based definition for LARS as variable or unpredictable bowel function, altered stool consistency, increased stool frequency, repeated painful stools, emptying difficulties, urgency, incontinence, and soiling.

A diagnosis of LARS can be made when patients experience at least one of these symptoms which results in one of the following consequences: toilet dependence, preoccupation with bowel function, dissatisfaction with bowels, strategies and compromises, impact on; mental and emotional wellbeing, social and daily activities, relationships and intimacy, and/or roles, commitments and responsibilities. This standardised definition enables consistent reporting of LARS and more focused investigation into LARS pathophysiology (Keene et al 2020).

Measurement of LARS

A brief review of literature suggests accurately measuring LARS in a standardised manner is essential to better understanding the pathophysiology, as the use of a wide range of validated and unvalidated tools may contribute to the complexity of assessing this syndrome. The NICE Guideline NG151 (2020) suggest the best assessment tool is the LARS score, which is a self-administered questionnaire, is publicly available and is simple to administer and score. The scale is from 0 to 42 points with 0 to 20 points indicating that the patient does not have LARS, 21 to 29 points indicating minor LARS, and 30 to 42 points indicating major LARS. Use of this assessment tool was also supported by Sakr et al (2020) who found it was concise and had the ability to show the impact of a patient’s QoL. However, they believed it failed to accurately assess bowel function and recommended the use of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Bowel Function Instrument (MSK-BFI) as it had a broader scope, covering both the LARS symptoms and their consequences.

Treatment of LARS

Current management of LARS is most commonly reactive, experimental and symptom based due to a limited evidence base. As a result, the NICE Guideline NG151 (2020) recommends a conservative approach, with the majority of patients requiring non-invasive intervention such as dietary manipulation (laxatives, bulking agents), pharmacological intervention (antidiarrhoeal medication or anti-spasmodic medication) or pelvic floor rehabilitation.

If these treatments are unsuccessful, the NICE Guideline NG151 suggests the patient is referred to secondary care where other options could be discussed such as sacral nerve stimulation and trans-anal irrigation such as peristeen plus.

At present, Carol’s physio team are undertaking a pelvic floor rehabilitation feasibility study. This is a 10week programme specifically designed to treat LARS that requires the patient to participate for only 1 hr per week. During this programme Carol and her team educate patients on what is normal bowel function and what is not, teach good bladder and bowel habits and toileting techniques, provide dietary advice and introduce the patient to pelvic floor muscle exercises supported by a home exercise programme. They also undertake bowel and pelvic floor training with a rectal catheter.

At Christchurch Hospital we are very fortunate to have a passionate and experienced motility team. In discussion with them, it became very clear they were highly knowledgeable and experienced with LARS and have seen significant improvements in a patient’s QoL, by following a similar approach to Carol’s pelvic floor rehabilitation study and the introduction of Peristeen Plus irrigation. They described a feeling of immense satisfaction with the work they do, when a patient says they’ve changed their lives!

Conclusions

In summary, I learnt that low anterior resection syndrome is a very complex patient outcome associated with rectal surgery that patients are often not aware of. Research suggests with more patient and surgical education available prior to and post procedure, with the ability to access LARS specific rehabilitation programmes could significantly improve a patients quality of life and reduce costs associated with chronic health care. I would encourage you to ask your local colo-rectal surgeons and or colo-rectal clinical nurse specialist how often do they encounter LARS and how do they educate and manage their patients if they develop this complication post-surgery? Perhaps with more knowledge we can better inform our patients and prevent months of poor quality of life.

Thank you to the NZgNC for their financial support, so that I could attend this conference.

References:

• Benli, S. Colak, T. Ozqur, M. ‘Factors influencing anterior/low anterior resection syndrome after rectal or sigmoid resections’ Turkish Journal of Medical Science. 2021; 51(2): 623–630.

• Cancer Council New South Wales (2022): (www. cancercouncil.com.au/bowel-cancer/treatment/ surgery/surgery-for-cancer-in-the-rectum/ )

• Cancer Society New Zealand. ‘Improving bowel function after treatment’ https://www.cancer. org.nz/cancer/types-of-cancer/bowel-cancer/ treatment-of-bowel-cancer

• Colo-rectal Cancer Alliance, United States of America (https://www.ccalliance.org)

• Keane, C. Fearnhead N.S. Bordeianou L.G. Christensen, P. Basany, E. Laurberg, S. Mellgren, A. Messick, C. Orangio, G.R. Verjee, A. Wing, K. Bissett, I.P. ‘International consensus definition of low anterior resection syndrome’ ANZ Journal of Surgery. Volume 90, Issue3 (March 2020): Pages 300307.

• https://www.colorectalsurgeonsnewcastle.com.au

• National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; Colorectal Cancer (update) ‘Optimal management of low anterior resection syndrome’ NICE Guideline NG151 (2020).

• Sakr, A. Sauri, F. Aless, M. Zakarnah, E. Alawfi, H. Torky, R. Kim, H.S. Yoon Yang, S. Kim N.K. ‘Assessment and management of low anterior resection syndrome after sphincter preserving surgery for rectal cancer’ Chinese Medical Journal, Vol.133 (2020) pg.1824-1833.

• Varghese, C. Wells, C.I. Bissett, I.P. O’Grady, G. Keane, C. ‘The role of colonic motility in low anterior resection syndrome’, Frontiers in Oncology, 16th September (2022) pg. 01-14.